Abstract

Covalent modification of α7 W55C nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) with the cysteine-modifying reagent [2-(trimethylammonium)ethyl] methanethiosulfonate (MTSET+) produces receptors that are unresponsive to acetylcholine, whereas methyl methanethiolsulfonate (MMTS) produces enhanced acetylcholine-gated currents. Here, we investigate structural changes that underlie the opposite effects of MTSET+ and MMTS using acetylcholine-binding protein (AChBP), a homolog of the extracellular domain of the nAChR. Crystal structures of Y53C AChBP show that MTSET+-modification stabilizes loop C in an extended conformation that resembles the antagonist-bound state, which parallels our observation that MTSET+ produces unresponsive W55C nAChRs. The MMTS-modified mutant in complex with acetylcholine is characterized by a contracted C-loop, similar to other agonist-bound complexes. Surprisingly, we find two acetylcholine molecules bound in the ligand-binding site, which might explain the potentiating effect of MMTS modification in W55C nAChRs. Unexpectedly, we observed in the MMTS-Y53C structure that ten phosphate ions arranged in two rings at adjacent sites are bound in the vestibule of AChBP. We mutated homologous residues in the vestibule of α1 GlyR and observed a reduction in the single channel conductance, suggesting a role of this site in ion permeation. Taken together, our results demonstrate that targeted modification of a conserved aromatic residue in loop D is sufficient for a conformational switch of AChBP and that a defined region in the vestibule of the extracellular domain contributes to ion conduction in anion-selective Cys-loop receptors.

Keywords: Crystal Structure, Crystallography, Ion Channels, Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors, X-ray Crystallography

Introduction

Cys-loop receptors (CLRs)2 belong to a class of ligand-gated ion channels that are involved in fast synaptic transmission in the central nervous system and the neuromuscular junction. This transmission can either be excitatory or inhibitory depending on the charge of ions that pass through the ion conduction pathway of the channel. Excitatory transmission is mediated by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) and 5-HT3 serotonin receptors, which selectively pass cations. On the other hand, inhibitory transmission is mediated by glycine receptors (GlyR) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAA and GABAC) receptors, which selectively conduct anions. In both types of receptors, the ion conduction pathway lies along the central axis formed by five channel subunits, which can either be identical for homomeric CLRs or non-identical for heteromeric CLRs. Opening and closing of the ion conduction pathway is controlled by a gate that is allosterically coupled to the extracellular ligand-binding domain (for a recent review see Ref. 1).

Detailed structural data are still lacking for an intact eukaryotic CLR, but structural information has been obtained from 4 Å resolution electron microscopic images of the Torpedo nAChR (2) and higher resolution x-ray crystal structures of AChBP, a molluscan homolog of the extracellular domain of nAChRs (3, 4), the monomeric α1 nAChR subunit (5), and two prokaryotic homologs ELIC (6) and GLIC (7, 8), which presumably represent the closed and open state of a CLR. Despite their different pharmacological properties, these CLRs share a common architectural arrangement of aromatic residues in their ligand-binding site. The ligand-binding site for CLRs is found at the interface between two subunits and ligands interact with amino acids from both the principal face (containing loops A, B, and C) and complementary face (containing loops D, E, and F). We have focused our attention on an aromatic residue that lies on the complementary face of the binding pocket and is highly conserved among eukaryotic and prokaryotic CLRs.

Recently, we found that the tryptophan residue at position 55 of the rat α7 nAChR (Trp-55) was the site where synthetic peptides derived from apolipoprotein E non-competitively inhibited α7 receptors through hydrophobic interactions (9). In addition, when Trp-55 was mutated to alanine, the α7 W55A nAChR desensitized more slowly and recovered from desensitization more rapidly than wild-type receptor (10). Mutating Trp-55 to other aromatic residues (Phe or Tyr) had no significant effect on the kinetics of desensitization, whereas mutation to various hydrophobic residues (Ala, Cys, or Val) significantly decreased the rate of onset and increased the rate of recovery from desensitization (10). To gain insight into possible structural rearrangements during desensitization, we probed the accessibility of Trp-55 by mutating Trp-55 to cysteine (α7 W55C) and tested the ability of various sulfhydryl reagents to react with this cysteine (10). Modification with several positively charged sulfhydryl reagents, including [2-(trimethylammonium)ethyl] methanethiosulfonate (MTSET+), produced α7 W55C nAChRs that became unresponsive to acetylcholine, whereas a neutral sulfhydryl reagent methyl methanethiolsulfonate (MMTS) enhanced acetylcholine-activated currents by nearly 60% (10). These data suggested that Trp-55 plays an important role in both the onset and recovery from desensitization in the rat α7 nAChR, and suggested that Trp-55 may be a potential target for modulatory agents operating via hydrophobic interactions.

However, these data left unresolved how modification of loop D with MTSET+ or MMTS leads to two clearly distinct functional effects. MTSET+ modification renders α7 W55C receptors unresponsive to acetylcholine, whereas MMTS modification produces receptors with enhanced responses to acetylcholine. In this study, we used AChBP to determine x-ray crystal structures of the homologous Y53C mutant modified either with MTSET+ alone or MMTS in the presence of acetylcholine. We investigated whether structural changes of methanethiosulfonate (MTS)-modified AChBP correlate with the opposing functional effects of MTSET+ and MMTS observed on α7 W55C nAChRs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

AChBP-Y53C Expression, Purification, and MTSET+ Modification

The mutant cDNA encoding Y53C AChBP from Aplysia californica was engineered using a QuikChange strategy (Stratagene) and verified by sequencing. Baculovirus was produced using the Bac-to-Bac expression system according to the manufacturer's guidelines (Invitrogen). Untagged AChBP-Y53C was expressed in Sf9 insect cells and purified as previously described (11). In brief, medium from Sf9 cells was harvested 3–4 days after infection with P2 baculovirus and concentrated on Q Sepharose Fast Flow (GE Healthcare). Y53C AChBP was further purified by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 column and ion exchange on a monoQ column (GE Healthcare). C-terminally His-tagged Y53C AChBP was purified on a Ni-Sepharose column (GE Healthcare) and pentameric protein was isolated on a Superdex 200 gel filtration column. Protein was concentrated to 5–6 mg/ml on a Centriprep filter (Amicon) with a cut-off of 30 kDa.

[2-(trimethylammonium)ethyl]Methanethiosulfonate bromide (MTSET+) and methyl methanethiolsulfonate (MMTS) were purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals. MTSET+ was dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 1 m, and aliquots were stored at −20 °C. Dilutions of 100 mm MTSET+ were prepared fresh in double-distilled water and stored on ice immediately before starting covalent protein modification. Modification of Y53C AChBP with MTSET+ or MMTS was carried out on ice at a final concentration of 1 mm MTSET+ or MMTS during 1 h. To ensure maximal modification of AChBP-Y53C a second aliquot of MTS reagent was added and the reaction was extended for another hour. Covalent modification of Y53C AChBP with MTSET+ or MMTS was analyzed with mass spectrometry. Non-reacted MTS reagents or hydrolysis products were removed from the protein solution by dialysis prior to crystallization.

Mass Spectrometry of MTS-modified AChBP-Y53C

The AChBP protein sample (3 μg/μl) was mixed with 10 μl of dissolution buffer (0.5 m TEAB; ABI) and 8 μl of trypsin solution (20 μg/ml) (sequencing grade from Promega). After incubation overnight at room temperature, the sample was loaded into a C18 Ziptip, and peptides were eluted with 2 μl of 80% acetonitrile/7.0 mm TFA. Of the eluant 0.5 μl was spotted on a MALDI metal plate, mixed with 1 μl of matrix (7 mg of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 1 ml, 50% acetonitrile, 0.1% TFA, 10 mm ammonium phosphate), and analyzed on a ABI 4800 Proteomics Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). CID was performed at 2KV, the collision gas was air. MS/MS spectra were collected from 2500 laser shots. MALDI MS and MALDI/MS/MS analysis of the protein digests was used to identify and map the sites of modification. This mass spectrometry analysis showed that >75% of Cys-53 was modified by MTSET+, the remaining fraction is unmodified Cys-53 even in the presence of excess amounts of MTSET+. For MMTS-modified protein the analysis indicated that >90% of Cys-53 is covalently bound to MMTS.

Crystallization and Structure Determination of MTSET+-modified AChBP-Y53C

Initial crystallization screens were carried out at 20 °C using nanoliter-dispensing robotics (TTP Labtech). Optimal crystals for AChBP Y53C-MTSET+ grew at 4 °C under the following chemical conditions: 150 mm KSCN, bistrispropane, pH 8.5, and 14% PEG3350. Cryoprotection was achieved by adding glycerol to the mother liquor in 5% increments to a final concentration of 25%. AChBP Y53C-MMTS was co-crystallized with acetylcholine at a final protein concentration of 6 mg/ml and 3 mm acetylcholine. Optimal crystals grew at 4 °C under the following chemical conditions: 200 mm NH4(H2PO4), 100 mm Tris, pH 8.5, and 50% MPD. Cryoprotection was achieved by a quick crystal soak in the well solution. Crystals were flash-cooled by immersion in liquid nitrogen.

Diffraction data for Y53C-MTSET+ were collected to 3.0 Å at beamline ID14–1 of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF, Grenoble). The structure was solved by molecular replacement using MOLREP (12) and the unliganded Aplysia AChBP structure with PDB code 2UZ6. The model contains two pentamers in the asymmetric unit and was refined using PHENIX (13) with TLS and NCS restraints. Manual building was carried out using COOT (14). The MTSET+-modified side chain at position 53 was built into the simple Fo − Fc density map after refinement of a model in which the side chain at position 53 was omitted. Coordinates and topology file for MTSET+ were obtained from the PRODRG server (15). The occupancy of MTSET+ at each of the 10 binding sites was refined with PHENIX to an average value of 87%.

Diffraction data for Y53C-MMTS in complex with acetylcholine were collected to 2.7 Å at beamline ID23–2 (ESRF, Grenoble). The structure was solved by molecular replacement and refined using a strategy similar to the one described above. The model contains one pentamer in the asymmetric unit and was refined with BUSTER (16) using TLS and NCS restraints. Inspection of the simple Fo − Fc density map revealed two noticeable blobs in each binding pocket. Acetylcholine molecules were manually placed into density with COOT using coordinates and restraints obtained from the PRODRG server. The MMTS-modified side chain was built into Fo − Fc density map after refinement of the model in which the side chain at position 53 was omitted. Diffraction data were processed with MOSFLM for the Y53C-MTSET+ data set and XDS for the Y53C-MMTS data set. Validation of the final model was carried out with MOLPROBITY (17, 18). All model figures were prepared with PYMOL (DeLano Scientific).

Competitive Binding Assays with AChBP-Y53C

Competition binding assays were performed in buffer (PBS, 20 mm Tris, 0.05% Tween, pH 7.4) in a final assay volume of 100 μl. [3H]epibatidine (GE Healthcare, specific activity 56 Ci/mmol) was used as the radioligand at 2.23 nm. Ligand was added to 10–50 ng His-tagged Y53C AChBP, mixed with 200 μg PVT Copper His-Tag SPA beads (GE Healthcare) and incubated for 1.5 h at room temperature under continuous shaking. The SPA beads were allowed to settle during 2–4 h and the radioactivity was measured in a Wallac 1450 MicroBeta liquid scintillation counter. All radioligand binding data were evaluated by a nonlinear, least-squares curve fitting procedure using Graphpad Prism (version 5, GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). All data are represented as the mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments.

Single Channel Recordings from α1 GlyRs

Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK) cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin, in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. HEK cells were co-transfected with GFP and wild-type or mutant α1 GlyR cDNA using a calcium phosphate transfection kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cover slips containing transfected HEK cells were transferred to a chamber containing (in mm): 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. Cells were visualized using a Nikon Eclipse TE300 microscope equipped for fluorescence detection. Borosilicate patch pipettes (3–6 MΩ) were filled with extracellular solution containing 100 μm glycine. Currents were recorded in the cell-attached configuration at −30, −60, and −90 mV. Experiments were performed at room temperature (22 °C) using an Axopatch-200A amplifier connected to a Digidata 1322A and pCLAMP software (version 10.1). Currents were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz.

RESULTS

X-ray Crystal Structures of MTS-modified Y53C AChBP

To investigate whether AChBP is a valid tool for structural studies of MTS-modified cysteine mutants, we investigated the pharmacological effects of MTSET+- and MMTS-modification on the homologous Y53C mutant in AChBP from Aplysia californica, Ac-AChBP (see Table 1). Mutation of Tyr-53 to cysteine leads to a reduction of [3H]epibatidine binding, whereas MMTS modification does not significantly alter binding. Nicotine displacement is significantly lowered in both Y53C and its MMTS-modified protein. However, acetylcholine binding is selectively affected only in the MMTS-modified Y53C, suggesting that acetylcholine may address a different binding configuration. Upon modification with MTSET+, no binding with [3H]epibatidine could be detected. This parallels the observation that α7 W55C nAChRs become unresponsive to acetylcholine after modification with MTSET+ (10). Combining these data suggest that AChBP Y53C is sensitive to modification with MTS reagents and provides a model to understand the effects of MMTS and MTSET+ modification at the structural level.

TABLE 1.

Binding affinities of epibatidine, nicotine, and acetylcholine for wild type Ac-AChBP, Y53C AChBP, and the MMTS- and MTSET+-modified Y53C proteins

Student's t-test was used to determine significance levels.

| Kd [3H]EB | Ki nicotine | Ki acetylcholine | |

|---|---|---|---|

| nm | μm | μm | |

| wt Ac-AChBP | 8.47 ± 1.93 | 0.77 ± 0.06 | 64.4 ± 8.6 |

| Y53C | 26.76 ± 4.02a | 2.78 ± 0.47b | 60.65 ± 2.53 |

| Y53C-MMTS | 19.11 ± 3.77a | 3.05 ± 0.28b | 98.3 ± 0.8a |

| Y53C-MTSET+ | NBc | NB | NB |

a Different from wt p < 0.05.

b Different from wt p < 0.001.

c NB, no binding.

Next, we determined crystal structures of Ac-AChBP in which the homologous aromatic residue Tyr-53 was mutated to cysteine and subsequently modified with either MTSET+ or MMTS. The crystal structure of Ac-AChBP Y53C with MTSET+ was solved from diffraction data to a resolution of 3 Å (Table 2). The asymmetric unit contains two pentamers, which are in an upside-down orientation relative to each other and interact through an interface that involves two neighboring C-loops (Fig. 1A). As a result of this crystal contact, one of these C-loops is more contracted compared with the conformation of all other C-loops in this pentamer (see supplemental Fig. S1). Mass spectrometry of MTSET+-modified Y53C and inspection of difference electron density maps indicated the attachment of an MTSET+ side chain to Y53C (Fig. 1A). Contact analysis of surrounding residues in the ligand-binding pocket shows that the MTSET+ side chain interacts with the side chains of Gln-36 and Ser-165 in loop F and Tyr-91 in loop A (Fig. 1A). Superposition of each of the 5 monomers shows a variable conformation of the MTSET+ side chains (see supplemental Fig. S1). Together with partial covalent modification, flexibility of the MTSET+ side chain might account for the weak electron density observed at some positions in the crystal structure. High flexibility of the MTSET+ side chain and partial density was also observed in the crystal structure of MTSET+-modified Sortase B from Staphylococcus aureus (PDB code 1QWZ), despite the higher resolution (1.7 Å) of the diffraction data (19).

TABLE 2.

Crystallographic and model refinement statistics

| Ac-AChBP Y53C+MTSET+ | Ac-AChBP Y53C+MMTS+acetylcholine | |

|---|---|---|

| Data statistics | ||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9334 | 0.8726 |

| Spacegroup | P41 21 2 | C2221 |

| Unit cell parameters (Å) | a = b = 144.8, c = 274.6 | a = 82.1, b = 119.4, c = 267.7 |

| Resolution limits (Å) | 100-3.15 (3.32-3.15) | 47.6-2.80 (2.87-2.80) |

| Rsyma (%) | 18.2 (41.3) | 13.3 (59.4) |

| Rmeasb (%) | 20.1 (45.8) | 16.7 (71.7) |

| Rpimc (%) | 8.5 (19.4) | 7.1 (44.6) |

| I/σ(I) | 4.1 (1.9) | 11.8 (1.9) |

| Multiplicity | 5.3 (5.4) | 5.9 (3.3) |

| Data completeness (%) | 98.3 (98.9) | 92.2 (77.5) |

| Number unique reflections | 50724 (7358) | 31966 (2244) |

| Wilson B factor | 31.6 | 50.5 |

| Refinement and model statistics | ||

| R-factord (%) | 18.6 | 17.3 |

| Rfreee (%) | 23.6 | 21.9 |

| RMSD bond distance (Å) | 0.008 | 0.010 |

| RMSD bond angle (°) | 1.07 | 1.09 |

| Average B-factors | 63.0 (protein) | 47.1 (protein) |

| 90.1 (MTSET+ side chain) | 59.7 (MMTS side chain) | |

| 52.5 (ACh1) | ||

| 105.9 (ACh2) | ||

| 106.7 (PO43−) | ||

| 38.1 (H2O) | ||

| Ramachandran analysisf | ||

| Number of residues in favorable regions | 1595 (86.7%) | 834 (89.7%) |

| Number of residues in additional allowed regions | 244 (13.25%) | 96 (10.3%) |

| Number of residues in disallowed regions | 1 (0.05%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Total number of residues | 2060 | 1040 |

a ΣhklΣi|Ii(hkl) − 〈I(hkl)〉 |/ΣhklΣiIi(hkl), where Σhkl denotes the sum over all reflections, and Σi is the sum over all equivalent and symmetry-related reflections.

b Rmeas = Σhkl|√(N/(N − 1)) Σi|Ii(hkl) − 〈I(hkl)〉 |/ΣΣhklΣiIi(hkl).

c Rpim = Σhkl|√(1/(N − 1)) Σi|Ii(hkl) − 〈I(hkl)〉 |/ΣhklΣiIi(hkl).

d R-factor = Σ |Fobs − Fcalc |/ΣFobs.

e Rfree = R-factor for 5% of the data were not included during crystallographic refinement.

f Ramachandran analysis was carried out with PROCHECK in the CCP4 suite.

FIGURE 1.

A, left, crystal structure of Aplysia Y53C AChBP modified with MTSET+. The asymmetric unit contains two pentamers, which are in an upside-down orientation relative to each other and interact through two neighboring C-loops (indicated with arrow). The MTSET+-modified side chain is shown as spheres. Right, detailed stereoview of the ligand-binding pocket at the interface of two subunits. The principal face (+) is shown in yellow, complementary face (−) in blue. Conserved aromatic amino acids of the principal face as well as residues involved in interactions with the MTSET+-modified side chain (Gln-36, Tyr-91, and Ser-165) are shown in stick representation. 2Fo − Fc electron density around the Cys-55 side chain is shown as blue mesh with a contour level of 1.0 sigma. B, left, co-crystal structure of Y53C AChBP modified with MMTS and acetylcholine. The asymmetric unit contains 1 pentamer, shown along the 5-fold symmetry axis. The MMTS side chain and acetylcholine molecules are shown in sphere representation. Right, detailed stereoview of the ligand-binding pocket formed by a principal (yellow) and complementary (blue) subunit. Residues involved in ligand-receptor interactions are shown in stick representation. 2Fo − Fc density around the acetylcholine molecules and MMTS-modified side chain is shown as a blue mesh at a contour level of 1.0 sigma. C, sequence alignment showing the conservation of an aromatic amino acid (shown in “black”) in loop D of different Cys-loop receptors. D, stereoview of ligand contacts in the published crystal structure of Lymnaea AChBP in complex with a single carbamylcholine molecule (PDB code 1UV6 and Ref. 20).

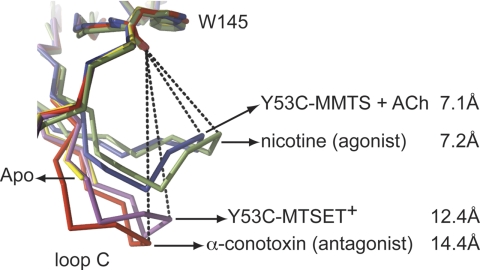

The conformational state of loop C and its relative contraction was quantified by measuring the distance between the carbonyl oxygen atom of the conserved Trp-145 and the γ-sulfur atom of Cys-188 in each subunit of the pentamer (Fig. 2). For one of the C-loops involved in the crystal contact this distance is 7.9 Å, compared with 12.45 ± 1.88 Å in all other subunits (magenta, Fig. 2). In comparison, this distance amounts to 7.23 ± 0.10 Å for loop C in a contracted conformation of the published nicotine-bound structure of AChBP (green, Fig. 2 and Ref. 20) and 14.38 ± 0.13 Å for loop C in an extended conformation of the α-conotoxin-bound structure (red, Fig. 2 and Ref. 11). The published crystal structure for apo AChBP revealed a disordered loop C (yellow, Fig. 2 and Ref. 21), which is most likely due to an intrinsic mobility of this loop in the unliganded state (22). These data indicate that MTSET+-modification of Cys-53 stabilizes Ac-AChBP in a conformational state that is similar to the antagonist-bound complexes with α-conotoxins (Fig. 2). This observation parallels the effect of MTSET+-modification on α7 W55C nAChRs, which produces receptors unresponsive to saturating concentrations of acetylcholine.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of C-loop conformation for Y53C-MTSET+ (magenta), Y53C-MMTS in complex with acetylcholine (blue), nicotine-bound state (green, PDB code 2BR7, Ref. 20), α-conotoxin ImI-bound state (red, PDB code 2C9T, Ref. 11), and apo state (yellow, PDB code 2W8E, Ref. 21). The dashed lines indicate the distances between the carbonyl oxygen of the conserved Tyr-145 residue in Aplysia AChBP and the γS atom of the vicinal disulfide bond.

To gain more insight into the potentiating effect of MMTS-modification of α7 W55C nAChRs upon application of acetylcholine, we also solved a crystal structure of MMTS-modified Y53C-AChBP in complex with acetylcholine. Mass spectrometry analysis of MMTS-modified Y53C AChBP indicated that >90% of the protein was covalently modified in the presence of excess amounts of MMTS. The crystal structure for MMTS-Y53C in complex with acetylcholine was solved from diffraction data to a resolution of 2.8 Å (Fig. 1B and Table 2). Difference electron density maps indicate that the cysteine side chain at position 53 was modified and that acetylcholine molecules occupy each of the five binding pockets (ACh1, Fig. 1B) at a position that is almost identical to the published carbamylcholine-bound structure of Ls-AChBP (Fig. 1D, CCh and Ref. 20). The quaternary amine group of ACh1 forms a cation-π interaction with the conserved aromatic residues of the principal face (shown in yellow in Fig. 1B). Unexpectedly, electron density near the MMTS-modified side chain indicates the occupancy of a second acetylcholine molecule in the same binding pocket (ACh2, Fig. 1B). Contact analysis shows that the MMTS side chain closely interacts with this second acetylcholine molecule, together with residues of the complementary face, namely Thr-34, Gln-36, and Ser-165 (Fig. 1B). The conformation of loop C in this crystal structure was compared with the MTSET+-modified Y53C structure by measuring the distance between carbonyl oxygen atom of Trp-145 and the γ-sulfur atom of Cys-188, which amounts to 7.18 ± 0.02 Å (blue, Fig. 2). Together, these data show that the conformational state of MMTS-Y53C in complex with acetylcholine is distinct from MTSET+-Y53C and offer a possible explanation for the potentiating effect of MMTS on acetylcholine-evoked currents in α7 W55C nAChRs.

Phosphates Ions Are Bound in the Vestibule of AChBP

Surprisingly, we also found peaks in the difference map that are localized in the vestibule of AChBP (Fig. 3, A and B). These peaks were interpreted as phosphate ions, which were present in the crystallization solution at a concentration of 200 mm. In total, there are ten phosphate ions bound in the vestibule, which are arranged in two pentagonal layers. The upper layer contains five phosphate ions at a distance of 9 Å apart (Fig. 3D, ring 1) that occupy the same positions as sulfate ions observed in a previous study (23). These sulfates are stabilized through interaction with Arg-95, which is in an equivalent position to a conserved positively charged residue in anion-selective Cys-loop receptors and a conserved negatively charged residue in cation selective receptors (for example, Asp-97 in the muscle α1 nAChR subunit). This residue, which lies near the transmembrane interface, was therefore suggested to stabilize cations before entry into the channel pore (23). However, in the MMTS-Y53C crystal structure, we find a second layer of phosphate ions in a pentagonal arrangement at a closer distance of 7 Å apart (Fig. 3D, ring 2). Phosphates in this lower ring interact directly with Lys-40 or through water molecules involved in hydrogen bonds with Glu-47 and Asp-49 in AChBP. A detailed interaction of residues and surrounding water molecules involved in hydrogen bonding of phosphate ions is shown in Fig. 3C.

FIGURE 3.

A, MMTS-Y53C crystal structure of AChBP shows localized phosphate ions in the vestibule. The pentamer is shown along the 5-fold axis of symmetry with the N terminus pointing away from the viewer. B, detailed view of the anion-binding site in AChBP as seen along the 5-fold symmetry axis from the intracellular side. Ten phosphate ions (yellow) are bound and interact with Lys-40 and Arg-95 (green), Glu-47 and Asp-49 (orange). Phosphate ions and interacting residues are shown in stick representation. The blue mesh around phosphate ions is electron density from a 2Fo − Fc map contoured at a level of 1.0 sigma. Dashed lines indicate distances between two neighboring phosphate ions, 9.3 Å for the upper layer (ring 1), and 7.1 Å for the lower layer (ring 2). C, detailed interaction of residues from a single subunit with phosphate ions in the vestibule. Water molecules are represented as red spheres. Dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds. D, stereoview from the side of the anion-binding site shows two layers of phosphate ions in a pentagonal arrangement. For clarity, phosphate ions are shown as yellow spheres with a radius of 1 Å. The upper layer (ring 1) matches the position of bound sulfate ions in a previously published study (23).

The observation that sulfates as well as phosphates bind in a defined location of the vestibule of AChBP suggests that this region functions as a general anion-binding site. Therefore, we questioned whether chloride anions may interact in a similar manner in the vestibule of anion-selective Cys-loop receptors, such as GABAA-R and GlyR. Sequence alignment with other Cys-loop receptors indicates that a residue of ring 1 (Arg-95 in Ac-AChBP) matches a conserved negatively charged residue, for example Asp-97 in α1 nAChR (Fig. 4A). In contrast, anion-selective Cys-loop receptors contain 1 or 2 adjacent positively charged residues at this position, for example Lys-105/Lys-106 in the α1 GABAA-R and Lys-104/Gly-105 in the α1 GlyR. Additionally, alignment of residues Glu-47 and Asp-49 in ring 2 of AChBP indicates the conservation of a negative charge in anion-selective Cys-loop receptors, for example Glu-59 in the α1 GABAA-R and Asp-57 in the α1 GlyR (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

A, side view of the GLIC pore (8) illustrates the relative position of the homologous ring sites and the selectivity filter at the bottom of transmembrane segments M1 and M2. The sequence alignment shows the conservation of charged residues in ring 1 (Arg-95 in AChBP) and ring 2 (Glu-47 and Asp-49 in AChBP) among different members of the Cys-loop receptor family. B, single channel responses were obtained from wild-type and mutant α1 GlyR using 100 μm glycine in the cell-attached configuration at −30, −60, and −90 mV. Mutant ring 1 contains K104A and G105D, mutant ring 2 contains D57I and R59T, mutant ring 1 + 2 is the quadruple mutant. B, wild-type α1 GlyR; C, mutant ring 1; D, mutant ring 2; E, mutant ring 1 + 2. Mutant ring 2 was only active at −60 and −90 mV. All-point histograms of current amplitude (bin width of 0.1 pA) were fitted by the sum of two Gaussian functions (right side; B, C, D, E). F, single channel conductances were derived from the slope of the current-voltage relationship; (72 pS) wild type, (46 pS) mutant ring 1, (27 pS) mutant ring 2, and (23 pS) mutant ring 1 + 2.

We investigated whether residues of ring 1 and ring 2 have a conserved role as anion-binding sites in the anion-selective α1 GlyR. Therefore, we mutated positions K104A and G105D (ring 1) and D57I and R59T (ring 2) to the corresponding residues in the α1 nAChR. Expression into Xenopus oocytes showed that these mutants were functional and had a reversal potential that was identical to wild-type α1 GlyR (data not shown), indicating that ion selectivity is not affected. Next, we investigated whether charge alterations affect the conductance of Cl− ions and recorded single channel activity evoked by 100 μm glycine in the cell-attached configuration on HEK293 cells expressing α1 GlyR mutants (Fig. 4, B–E). Compared with wild-type GlyR, the mutants show a decreased current amplitude at all potentials tested (Fig. 4, B–E). A current amplitude versus potential plot is linear (data not shown), allowing us to calculate the unitary conductance (slope of the line). The single channel conductance was decreased by 40% for mutant ring 1, by 60% for mutant ring 2, and by 70% for the quadruple mutant ring 1 + 2 (Fig. 4F). The effects of these mutations in ring 1 and ring 2 on single channel conductance were not additive since the quadruple mutation shows conductance levels similar to mutant ring 2. Furthermore, the ring 2 mutations result in the loss of activity at −30 mV suggesting that these residues are not only critical for channel conductance, but may also be involved in gating. These results demonstrate that conserved charges at two adjacent sites in the extracellular domain of the α1 GlyR contribute to ion selection and permeation. Coordinates and structure factors for Y53C-MTSET+ and Y53C-MMTS with acetylcholine have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 2XZ6 and 2XZ5, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Substituted cysteine accessibility scanning (SCAM) is a widely used method to study the relationship between structure and function of ion channels (24). With the availability of an increasing number of x-ray crystal structures for ion channels, SCAM is now frequently employed to test the validity of three-dimensional models in the context of channel dynamics and their lipid membrane environment (25–27). SCAM has powerful advantages in that the method allows real-time monitoring of the reaction speed between the MTS reagent and the targeted cysteine residue for the closed, open, or desensitized state of the channel. However, this reaction is typically followed indirectly by measuring changes in the functional properties of ion channels such as ion conduction, voltage dependence of activation or ligand activation. Because of the indirect nature of this method, it is not always possible to establish a clear relationship between the observed functional effects of MTS modification and the underlying conformational changes of the channel.

In this study, we report the first x-ray crystal structures of an MTS-modified cysteine mutant of the nAChR homolog AChBP. We used the homologous mutant of α7 W55C nAChRs, which is oppositely regulated by two different MTS reagents, namely MTSET+ and MMTS (10), to investigate the correlation between structure and function. We previously demonstrated that modification of α7 W55C nAChRs with MTSET+ produces receptors that become unresponsive to saturating concentrations of acetylcholine (10). The crystal structure of MTSET+-modified Y53C AChBP shows that loop C is stabilized in a conformational state that resembles the antagonist-bound state. This result suggests that the unresponsive behavior of MTSET+-modified α7 W55C nAChRs may arise from a similar stabilization of the receptor in an antagonist-bound state. This also suggests that the conformation of loop C is correlated with the activational state of the receptor. In contrast to MTSET+-modified α7 W55C nAChRs, we previously showed that modification of α7 W55C nAChRs with MMTS enhances acetylcholine-evoked currents by nearly 60% (10). The crystal structure of MMTS-modified Y53C AChBP shows that loop C is strongly contracted, similar to other agonist-bound structures. We also observed that two acetylcholine molecules occupy the binding pocket, which possibly explains the potentiating effect of acetylcholine on MMTS-modified α7 W55C nAChRs. One of these acetylcholine molecules faces the principal binding site and occupies a position that overlaps with the binding mode observed in the related carbamylcholine-bound structure of AChBP. The second acetylcholine molecule interacts with residues of the complementary face, including the MMTS-modified side chain of Cys-53. Therefore, we propose that the potentiating effect of MMTS on α7 W55C nAChRs arises from a favorable interaction with the MMTS-modified side chain that stabilizes two acetylcholine molecules in the ligand-binding site. Together, both AChBP crystal structures parallel our observations from functional studies on α7 W55C nAChRs, and offer possible explanations for the opposing effects of MTSET+ and MMTS. Our results suggest that targeted modification of a single residue in loop D is sufficient to trigger conformational changes of AChBP.

The functional importance of residues in loop D has been demonstrated by mutagenesis studies in different CLRs. Mutation of the homologous W55 residue in the GABAA-R γ2-subunit, F77C, abolished binding by [3H]Ro15–1788 and the benzodiazepine [3H]flunitrazepam. Mutation of neighboring residues in loop D, A79C and T81C, caused a 10-fold reduction in the affinity of the tranquilizers eszopiclone and zolpidem (28). In the GABAA-R α1-subunit, it was shown that for the homologous Trp-55 subtle changes were caused by unnatural amino acid mutations (29). In the muscle nAChR it was shown that mutation W57F in the δ-subunit and W55F in the ϵ-subunit have only minor effects on acetylcholine-sensitivity but mainly affect channel gating by reducing the channel opening rate (30). In insect nAChRs, it was shown that the basic Arg and Lys residues at positions +2 and +4 of the homologous W55 residue are responsible for the high affinity of the insecticide imidacloprid and related neonicotinoids (31). Mutation of loop D residues N55S and V56I in the human nAChR β4-subunit, which are at positions −2 and −1 of the homologous Trp-55 residue, abolishes sensitivity to TMAQ, a novel agonist for β4-containing nAChRs (32). In a related study it was shown that mutations N55S, V56I, T59K, and E63T in the human nAChR β2-subunit reduce the affinity of acetylcholine and nicotine, while having little to no effect on the affinity of epibatidine and dimethylphenylpiperazinium (DMPP) (33).

In addition to loop D, accumulating evidence implicates loop C as a structural component that is key to both ligand binding and subsequent conformational changes underlying CLR activation, inhibition, and desensitization (34). The important role of loop C derives from a large body of work using x-ray crystallography (11, 35–37), molecular dynamics simulation (38–40), site-directed mutagenesis (41–44), and electrophysiology (45, 46). The data from these studies demonstrates that loop C is flexible in the non-liganded form (22, 37) and adopts distinct conformations upon agonist or antagonist binding. Loop C assumes a contracted configuration with agonists bound (corresponding to either the open or desensitized state of the receptor) and takes on an extended configuration with antagonists bound (corresponding to the closed state of the channel (11, 35, 36). More recent work suggests that the degree of loop C movement may correspond to agonist efficacy (37). Movement in the ligand binding domain is thought to propagate from the extracellular domain to the pore region to allow activation or inhibition of ion flux. This transduction of signal can be understood both as a sequence of chemical events (47) or as coordinated movements or rotations of the whole extracellular domain (40, 48, 49).

Unexpectedly, we observed electron density that could be interpreted as phosphate ions in the vestibule of AChBP at a location that is very near to the interface with the transmembrane domain in integral Cys-loop receptors. The contribution of rings of charged amino acids to channel conductance has previously been demonstrated in the Torpedo nAChR (50), but detailed insight into the mechanism of ion conduction was lacking. Structural insight into selection of ions in the extracellular domain of Cys-loop receptors was obtained from a crystal structure containing 5 sulfate ions near residue Arg-95 in the vestibule of AChBP (23). Hansen et al. demonstrated that this residue, which corresponds to a highly conserved Asp in cation-selective Cys-loop receptors, affects single channel conductance upon charge reversal mutations in the muscle nAChR. In our structure, we observe 10 phosphate ions bound to a cluster of charged residues that involve Lys-40, Glu-47, Asp-49, and Arg-95. The phosphate ions are arranged in two pentagonal layers separated by a distance of less than 4 Å. The 5 phosphate ions in the upper layer (ring 1) occupy the same positions as the sulfate ions in the study from Hansen et al. and are arranged at a distance of 9 Å apart. Phosphate ions in the lower layer (ring 2) are spaced at a distance 7 Å apart and interact with Lys-40, Glu-47, and Asp-49. The observation that sulfates as well phosphates bind in a defined location of the vestibule of AChBP suggests that this region functions as a general anion-binding site. One of the binding site residues, Glu-47, is strictly conserved as a negatively charged amino acid (Asp or Glu) in anion-selective Cys-loop receptors, and hydrophobic (M, I, or V) in cation-selective Cys-loop receptors. Therefore, we hypothesized that chloride anions may interact in a similar manner with conserved negatively charged residues in anion-selective Cys-loop receptors, such as GABAA-R and GlyR. We demonstrated that mutation of homologous residues in ring 1 and ring 2 of the α1 GlyR causes a pronounced reduction in the single channel conductance. This result suggests a functional role of the extracellular domain of α1 GlyR in selection and permeation of anions. Our observation fits with molecular dynamics simulations of the nAChR (51) and the bacterial homolog GLIC (52), which demonstrated the existence of one or more cation reservoirs in the extracellular domain of these cation-selective Cys-loop receptors.

In conclusion, our study shows a good correlation between structure and function, and offers possible explanations for the opposite effects of MTSET+ and MMTS on α7 W55C nAChRs. We show that targeted modification of loop D plays a key role in defining the conformational state of AChBP. This hints at a contribution of a conserved aromatic residue in loop D that goes beyond its established role of shaping the ligand-binding site. This residue may contribute to a structural switch that discriminates between the activated and non-activated state of Cys-loop receptors. In addition, the unexpected observation of phosphate anions bound in the vestibule of AChBP parallels the functional role of two rings of charged residues in the extracellular domain of the α1 GlyR that contribute to ion selection and permeation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the ESRF and local contacts for assistance during data collection. We thank Titia Sixma for access to crystallization robotics during initial stages of the study. We thank Pattie Lamb for technical assistance.

This research was supported, in whole or in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, NIEHS (to E. A. G., J. C. S., and J. L. Y.), by Grants FWO-Vlaanderen (G.0330.06, G.0257.08), and the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office, Interuniversity Attraction Poles program (P6/31) (to J. T.), EU FP7 2020288 NeuroCypres (to C. U., A. B. S., and R. C. vd. S.), and KULeuven Onderzoekstoelage OT/08/048 (to S. V. S. and C. U.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 2XZ6 and 2XZ5) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- CLR

- Cys-loop receptor

- AChBP

- acetylcholine-binding protein

- nAChR

- nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- MMTS

- methyl methanethiolsulfonate

- MTSET+

- [2-(trimethylammonium)ethyl] methanethiosulfonate

- RMSD

- root mean square deviation from ideal geometry.

REFERENCES

- 1. Taly A., Corringer P. J., Guedin D., Lestage P., Changeux J. P. (2009) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8, 733–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Unwin N. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 346, 967–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brejc K., van Dijk W. J., Klaassen R. V., Schuurmans M., van Der Oost J., Smit A. B., Sixma T. K. (2001) Nature 411, 269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smit A. B., Syed N. I., Schaap D., van Minnen J., Klumperman J., Kits K. S., Lodder H., van der Schors R. C., van Elk R., Sorgedrager B., Brejc K., Sixma T. K., Geraerts W. P. (2001) Nature 411, 261–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dellisanti C. D., Yao Y., Stroud J. C., Wang Z. Z., Chen L. (2007) Nat. Neurosci. 10, 953–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hilf R. J., Dutzler R. (2008) Nature 452, 375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hilf R. J., Dutzler R. (2009) Nature 457, 115–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bocquet N., Nury H., Baaden M., Le Poupon C., Changeux J. P., Delarue M., Corringer P. J. (2009) Nature 457, 111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gay E. A., Bienstock R. J., Lamb P. W., Yakel J. L. (2007) Mol. Pharmacol. 72, 838–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gay E. A., Giniatullin R., Skorinkin A., Yakel J. L. (2008) J. Physiol. 586, 1105–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ulens C., Hogg R. C., Celie P. H., Bertrand D., Tsetlin V., Smit A. B., Sixma T. K. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 3615–3620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vagin A., Teplyakov A. (2010) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 22–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Adams P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L. W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., Terwilliger T. C. (2002) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schüttelkopf A. W., van Aalten D. M. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 1355–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bricogne G., Blanc E., Brandl M., Flensburg C., Keller P., Paciorek W., Roversi P., Smart O. S., Vonrhein C., Womack T. O. (2009) BUSTER, Version 2.8.0 Ed., Global Phasing Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davis I. W., Leaver-Fay A., Chen V. B., Block J. N., Kapral G. J., Wang X., Murray L. W., Arendall W. B., 3rd, Snoeyink J., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2007) Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W375–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen V. B., Arendall W. B., 3rd, Headd J. J., Keedy D. A., Immormino R. M., Kapral G. J., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2010) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zong Y., Mazmanian S. K., Schneewind O., Narayana S. V. (2004) Structure 12, 105–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Celie P. H., van Rossum-Fikkert S. E., van Dijk W. J., Brejc K., Smit A. B., Sixma T. K. (2004) Neuron 41, 907–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ulens C., Akdemir A., Jongejan A., van Elk R., Bertrand S., Perrakis A., Leurs R., Smit A. B., Sixma T. K., Bertrand D., de Esch I. J. (2009) J. Med. Chem. 52, 2372–2383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shi J., Koeppe J. R., Komives E. A., Taylor P. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 12170–12177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hansen S. B., Wang H. L., Taylor P., Sine S. M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 36066–36070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Karlin A., Akabas M. H. (1998) Methods Enzymol. 293, 123–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gandhi C. S., Clark E., Loots E., Pralle A., Isacoff E. Y. (2003) Neuron 40, 515–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ahern C. A., Horn R. (2005) Neuron 48, 25–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Broomand A., Elinder F. (2008) Neuron 59, 770–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hanson S. M., Morlock E. V., Satyshur K. A., Czajkowski C. (2008) J. Med. Chem. 51, 7243–7252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Padgett C. L., Hanek A. P., Lester H. A., Dougherty D. A., Lummis S. C. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 886–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Akk G. (2002) J. Physiol. 544, 695–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shimomura M., Yokota M., Ihara M., Akamatsu M., Sattelle D. B., Matsuda K. (2006) Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 1255–1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Young G. T., Broad L. M., Zwart R., Astles P. C., Bodkin M., Sher E., Millar N. S. (2007) Mol. Pharmacol. 71, 389–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Parker M. J., Harvey S. C., Luetje C. W. (2001) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 299, 385–391 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hibbs R. E., Johnson D. A., Shi J., Taylor P. (2006) J. Mol. Neurosci. 30, 73–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hansen S. B., Sulzenbacher G., Huxford T., Marchot P., Taylor P., Bourne Y. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 3635–3646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dutertre S., Lewis R. J. (2006) Biochem. Pharmacol. 72, 661–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hibbs R. E., Sulzenbacher G., Shi J., Talley T. T., Conrod S., Kem W. R., Taylor P., Marchot P., Bourne Y. (2009) EMBO J. 28, 3040–3051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gao F., Bren N., Burghardt T. P., Hansen S., Henchman R. H., Taylor P., McCammon J. A., Sine S. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8443–8451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cheng X., Wang H., Grant B., Sine S. M., McCammon J. A. (2006) PLoS Comput. Biol. 2, e134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yi M., Tjong H., Zhou H. X. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 8280–8285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Horenstein N. A., McCormack T. J., Stokes C., Ren K., Papke R. L. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5899–5909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hibbs R. E., Radic Z., Taylor P., Johnson D. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 39708–39718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Suryanarayanan A., Joshi P. R., Bikádi Z., Mani M., Kulkarni T. R., Gaines C., Schulte M. K. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 9140–9149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Venkatachalan S. P., Czajkowski C. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 13604–13609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pless S. A., Lynch J. W. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 27370–27376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Toshima K., Kanaoka S., Yamada A., Tarumoto K., Akamatsu M., Sattelle D. B., Matsuda K. (2009) Neuropharmacology 56, 264–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sine S. M., Engel A. G. (2006) Nature 440, 448–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Law R. J., Henchman R. H., McCammon J. A. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 6813–6818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Purohit P., Mitra A., Auerbach A. (2007) Nature 446, 930–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Imoto K., Busch C., Sakmann B., Mishina M., Konno T., Nakai J., Bujo H., Mori Y., Fukuda K., Numa S. (1988) Nature 335, 645–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang H. L., Cheng X., Taylor P., McCammon J. A., Sine S. M. (2008) PLoS Comput. Biol. 4, e41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nury H., Poitevin F., Van Renterghem C., Changeux J. P., Corringer P. J., Delarue M., Baaden M. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 6275–6280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.