Abstract

Children born very preterm, even with broadly normal IQ, commonly show selective difficulties in visuospatial processing and executive functioning. Very little, however, is known what alterations in cortical processing underlie these deficits. We recorded MEG while eight children born very preterm (≤32 weeks gestational age) and eight full-term controls performed a visual short-term memory task at mean age 7.5 years (range 6.4 – 8.4). Previously, we demonstrated increased long-range alpha and beta band phase synchronization between MEG sensors during STM retention in a group of 17 full-term children age 6–10 years. Here we present preliminary evidence that long-range phase synchronization in very preterm children, relative to controls, is reduced in the alpha-band but increased in the theta-band. In addition, we investigated cortical activation during STM retention employing synthetic aperture magnetometry (SAM) beamformer to localize changes in gamma-band power. Preliminary results indicate sequential activation of occipital, parietal and frontal cortex in control children, as well as reduced activation in very preterm children relative to controls. These preliminary results suggest that children born very preterm exhibit altered inter-regional functional connectivity and cortical activation during cognitive processing.

Keywords: preterm birth, beamformer, short-term memory, neural synchrony, functional connectivity

I. INTRODUCTION

Children born very preterm commonly exhibit selective deficits in visual processing and executive function, even when general intelligence is within the normal range [1]. Although considerable research has been conducted investigating neuroanatomical alterations associated with very preterm birth [see 2 for review], little is known about what differences in cortical processing underlie the selective cognitive difficulties common in this population.

A wealth of recent experimental evidence indicates that synchronization of neural oscillations is relevant for a variety of perceptual and cognitive processes. Active processing within a cortical region, for example, has been reliably related to local synchronization of gamma-band oscillations in a variety of contexts [3]. Synchronization of oscillations between cortical regions in a number of frequency ranges has also been associated with the formation of transient, functionally integrated networks for the performance of perceptual and cognitive tasks [3]. Previously, we demonstrated in a group of seventeen full-term children that visual short-term memory (STM) retention yields increased alpha and beta band synchronization between MEG sensors, indicative of the formation of a transient large-scale network supporting maintenance of the memory trace [4].

To investigate alterations in cortical processing in school age children who were born very preterm, we recorded MEG while very preterm children and age-matched controls performed a visual STM task. We present multiple preliminary results regarding phase synchronization between MEG sensors, indicative of task-dependent functional coupling between cortical regions, and from beamformer localization of gamma-band activation, reflecting the engagement of cortical regions, during task performance.

II. METHODS

Subjects

We recorded MEG while 8 very preterm children born ≤ 32 weeks gestation and 14 controls born at full-term performed a visual STM task. To examine group differences in long-range synchronization and gamma-band activation 8 age-matched pairs were selected (mean age 7.5 years, range 6.4 – 8.4 years). All 14 controls (age 6–10 years) were used in the beamformer analysis of gamma-band activation in full-term children. None of the very preterm children had significant brain injury on neonatal ultrasound, and all were born appropriate birth-weight for gestational age. All subjects had normal or corrected-to-normal vision.

Task

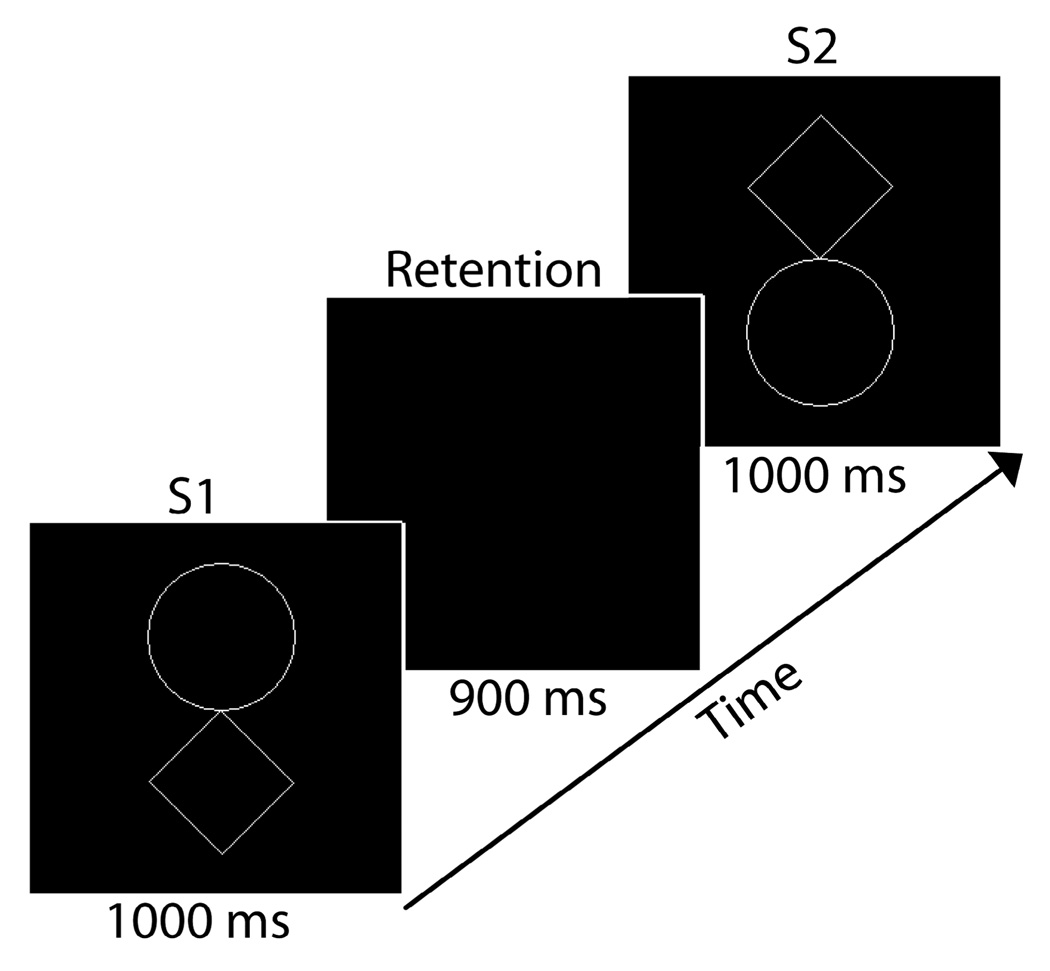

Subjects performed a visual STM task (Fig. 1) with stimuli adapted with permission [5]. On each of 180 trials subjects viewed an initial stimulus (S1) for 1000 ms, followed by a 900 ms retention interval during which they were required to maintain S1 in STM, followed by the presentation of a second stimulus (S2) for 1000 ms. Subjects were required to press a button on a response box to indicate if the shapes were the same or different. Additional task details are available in [4].

Fig. 1.

Time course of the stimulus display on a single trial

MEG Recording and Processing

MEG was digitized continuously at 1200 Hz using a 151 channel CTF system (Burnaby, Canada) and stored on disk for off-line analysis. Data were then standardized relative to sensor locations within and between subjects using a continuous head localization and correction procedure [6]. Epochs were extracted surrounding each trial and the record of ocular and nonocular artifacts was removed using a principal components analysis based procedure [7].

Phase Synchronization Analysis

Due to computational limitations imposed by pairwise comparisons, and to avoid spurious synchronization arising from volume conducted signals propagating to nearby sensors, we extracted data from a montage of 19 sensors distributed roughly evenly over the surface of the head to image the global pattern of long-range phase synchronization (sensors LF11, RF11, LF32, RF32, LC14, RC14, LO22, RO22, LO41, RO41, LT21, RT21, LT42, RT42, LO43, RO43, ZF03, ZCO3, ZP02). Data from each sensor were then digitally filtered at 1 Hz intervals between 6 and 60 Hz (passband = f ± 0.05f, where f is the filtered frequency). We then calculated the analytic signal

| (1) |

of the filtered waveform for each epoch, f(t), where f͂ (t) is the Hilbert transform of f(t) and , to obtain the instantaneous phase, ϕ(t), and amplitude, A(t), at each sample point. Phase locking values (PLVs) were computed from the differences of the instantaneous phases for analyzed sensor pairs for each analyzed frequency. For example, sensors j and k, at each point in time, t, across N available epochs [8]:

| (2) |

Phase locking values were then standardized relative to a baseline interval occurring before the onset of S1 in order to index changes in synchrony relevant to task demands by subtracting the mean baseline PLV at that frequency from the PLV at each data point and dividing the difference by the standard deviation of the PLV for the baseline interval at that frequency. Group differences were assessed by averaging data across subjects for each frequency and time point, and subsequently subtracting averaged data between groups. See [4] for additional details on synchronization analysis.

Beamformer Analysis

We employed synthetic aperture magnetometry (SAM) to localize gamma-band activation during STM retention in controls, and well as group differences between very preterm and control children. Beamformer analysis implements a spatial filter, estimating the contribution of each voxel in brain space to magnetic signals recorded at MEG sensors, by minimizing correlations with all other analyzed voxels. We imaged 30–50 Hz activity for each subject in four 225 ms time windows during STM retention (0–225, 225–450, 450–675, 675–900 ms) relative to a 225 ms baseline interval preceding the onset of S1. We averaged across the 14 controls to image gamma-band network dynamics in full-term controls. Group differences were assessed by averaging across the eight subjects in each group and subtracting averaged images across groups. Additional details about SAM can be found in [7]. Covariance matricies were regularized if noise spectral density exceeded an acceptable range.

III. RESULTS

Long-Range Phase Synchronization

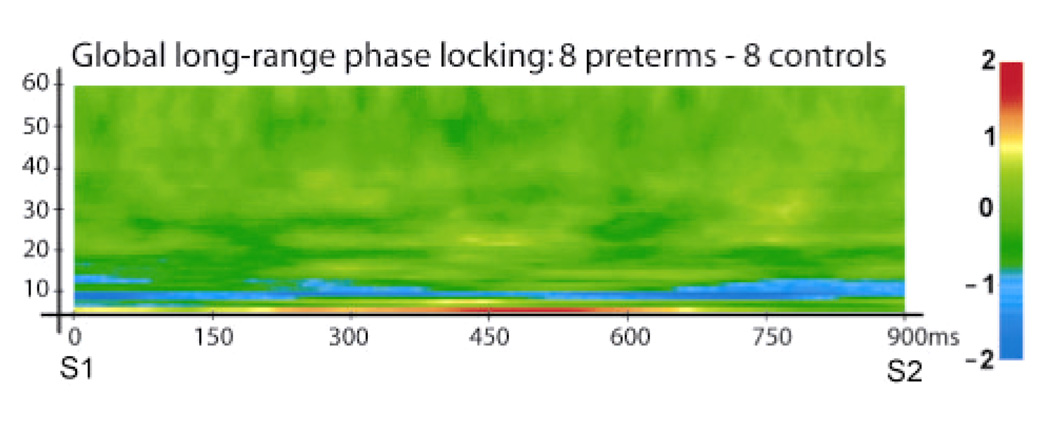

Preliminary results indicate that global patterns of long-range phase synchronization, calculated by averaging PLV across all 171 analyzed sensor pairs, was reduced in the alpha-band but increased in the theta-band in very preterm children, relative to full-term controls. These sustained group differences were centered at ~10 Hz and ~6 Hz, respectively.

Beamformer Analysis of Gamma-Band Activation

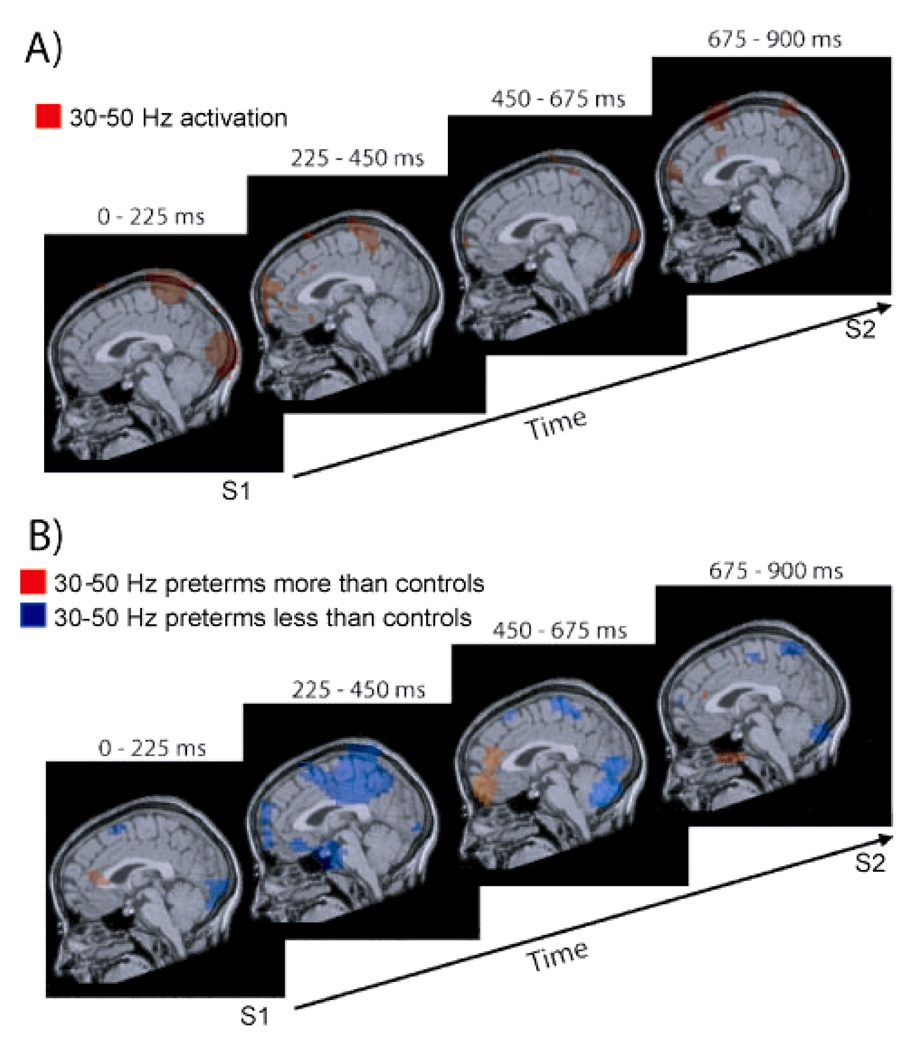

Our preliminary analysis of gamma-band activation in 14 controls indicates sequential stages of cortical activation during STM retention (Fig 3A). During the 0–225 ms interval activation was observed in early visual cortex and higher, posterior parietal, visual cortex. The subsequent 225–450 ms interval was characterized by activation in posterior parietal cortex and prefrontal cortex. During the 450–675 ms and 675–900 ms time windows residual activation was seen throughout the network of activated occipital, parietal and prefrontal cortical regions, with the addition of motor cortex activation during the 675–900 ms time window.

Fig. 3.

3A Gamma-band activation in four time intervals during STM retention in full-term controls. 3B Altered gamma-band activation in children born very preterm in four time intervals during STM retention; blue regions indicate reduced activation for very preterm children, orange regions indicate increased activation for very preterm children

Analysis of group differences yielded preliminary results indicating that very preterm children generally show less activation in within the identified network of task relevant cortical regions, although greater activation is observed for very preterm children in specific instances (Fig 3B). In the 0–225 ms interval very preterm children exhibited reduced activation in early visual cortex and in parietal cortex. In the 225–450 ms time window pronounced reductions were observed in posterior parietal cortex and prefrontal cortex. During the subsequent 450–675 ms interval reduced activation was found in early visual cortex and posterior parietal cortex, whereas increased activation was observed in prefrontal cortex for very preterm children. Reduced activation was seen for very preterm children throughout the task-relevant network of early visual, posterior parietal and prefrontal cortical regions during the final 675–900 ms interval.

IV. DISCUSSION

Long-Range Phase Synchronization

Synchronization between cortical regions has been implicated in the formation of transient, functionally integrated networks for the performance of particular tasks and to encode the features of percepts [3]. We previously reported long-range MEG synchronization in the alpha and beta bands during STM retention in children in this age range [4]. Such coherent large-scale network activity likely corresponds to functional coupling within a distributed network of cortical regions responsible for memory trace maintenance. Results of the present study indicate that this pattern of synchronization is altered in children born very preterm, with a pronounced and sustained loss of synchronization in the alpha-band as well as a sustained increase of synchronization in the theta-band. These preliminary results suggest that neural mechanisms underlying task-dependent functional coupling may be altered in children born very preterm. Previous research has associated slowing of peak oscillatory frequency in the MEG from the alpha-band toward the theta-band with dysrhythmic thalamocortical interactions [9]. Although such previous findings typically pertain to resting spectral power in MEG, the similarity of these alterations to those observed in the present data set suggest that dysrhythmic thalamocortical interactions may be relevant for altered long-range synchronization in very preterm children.

Gamma-Band Cortical Activation

Gamma-band activation within cortical regions is understood as reflecting active processing [3]. Preliminary results of gamma-band activation during STM retention in 14 control subjects indicate sequential activation of task-relevant cortical regions. Activation of early and higher visual cortex in the 0–225 ms time window presumably reflects processing of S1. Activation of prefrontal and parietal cortex during the subsequent 225–450 ms interval likely reflects recruitment of a network of executive and higher visual cortical areas responsible for maintaining the memory trace in STM. Activation of motor cortex in the 675–900 ms interval presumably reflects response preparation in anticipation of S2, and residual prefrontal, parietal and occipital activation in the 450–675 ms and 675–900 ms intervals likely reflect memory maintenance. This approach highlights the advantage of combined spatial and temporal resolution of MEG which permits the imaging of oscillations in specific frequency ranges in short time windows to reveal sequential processing in distributed cortical networks relevant to cognition.

This study provides preliminary evidence of altered gamma-band activation in children born very preterm, indicating that they have difficulty recruiting cortical regions relevant to STM retention. Reduced activation in very preterm children is seen in early visual cortex and parietal cortex 0–225 ms into the retention interval, suggesting problems in visual processing, consistent with previous behavioral research indicating selective visual processing difficulties [1]. Pronounced reductions in gamma-band activation in prefrontal and parietal cortex during the 225–450 ms interval, during which control children appeared to establish a network of prefrontal and posterior parietal cortical regions to maintain the memory trace in STM, highlights the apparent difficulty very preterm children exhibit in sufficiently activating cortical regions critical for task performance, consistent with previous work showing selective behavioral deficits in executive function in preterm children [1]. Interestingly, very preterm children showed increased gamma-band activation in prefrontal cortex predominantly during the 450–675 ms time window. This could be interpreted either as delayed executive processing (which occurred in the 225–450 ms interval for the full-terms) or as compensatory processing in very preterm children. If this indeed reflects compensatory processing, it is noteworthy that despite increased prefrontal activation in the 450–675 ms interval, reduced activation in parietal cortex is observed. This could be interpreted as increased executive effort leading to nonetheless diminished recruitment of higher visual cortex. Very preterm children also showed reduced activation in prefrontal, parietal and occipital cortex during the 675–900 ms interval, consistent with the overall pattern of reduced activation of task-relevant cortical areas.

V. CONCLUSIONS

Our preliminary findings indicate that cortical processing during STM retention is altered in children born very preterm. Altered long-range phase synchronization suggests that neural mechanisms mediating transient functional connectivity between brain regions may be abnormal in this group. Reduced and/or delayed gamma-band activation in task-relevant cortical regions suggests that children born very preterm may have difficulty recruiting networks of brain regions to support cognitive processing.

Fig. 2.

Alterations in global long-range phase locking during STM retention associated with very preterm birth. Data were averaged across all 171 analyzed sensor pairs, and differences are expressed in units of standard deviation from the pre-S1 baseline. Blue regions represent decreases in long-range synchronization; red and yellow regions denote increases

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant R01 HD039783 to R.E.G. and the BC Leading Edge Endowment Fund to U.R. We thank Ivan Cepeda, Gisela Gosse, Katia Jitlina, Julie Unterman and John Gaspar for their help collecting data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson PJ, Doyle LW. Cognitive and educational deficits in children born very preterm. Semin Perinatol. 2008;32:51–58. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart AR, Whitby EW, Griffiths PD, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and developmental outcome following preterm birth: review of current evidence. Dev Med & Child Neurol. 2008;50:655–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varela F, Lachaux JP, Rodriguez E, et al. The brainweb: phase synchronization and large-scale integration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;(2):229–239. doi: 10.1038/35067550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doesburg SM, Herdman AT, Ribary U, et al. Long-range synchronization and local desynchronization of alpha oscillations during short-term memory retention in children. Exp Brain Res. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-2086-9. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beery KE, Buktenica NA, Beery NA. Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration. 5th Ed. Psychological Corporation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson H, Moiseev A, Podin S, et al. Int Congr Ser 1300. 2007. Continuous head localization and data correction in MEG; pp. 623–626. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herdman AT, Cheyne D. A practical guide to MEG and beam-forming. In: Handy, editor. Brain signal analysis: advances in neuroelectric and neuromagnetic methods. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2009. pp. 99–140. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lachaux JP, Rodriguez E, Martinerie J, Varela F. Measuring phase synchrony in brain signals. Hum Brain Mapp. 1999;8:194–208. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)8:4<194::AID-HBM4>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Llinás RR, Ribary U, Jeanmonod D, et al. Thalamocortical dysrhythmia: a neurological and neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by magnetoencephalography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(26):15222–15227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]