Abstract

Objectives

To examine the recency and quality of the last Veterans Health Administration (VHA) visit for patients with depression dying from suicide.

Methods

We obtained services and pharmacy data for all 1843 VHA patients with recognized depressive disorders dying from suicide from April 1999-September 2004. We describe the location and timing of their final VHA visit. For visits occurring within 30 days of suicide, we examined three quality indicators: 1) evidence that mental illness was a focus of the final visit; 2) adequacy of antidepressant dosage, and 3) recent receipt of mental health services.

Results

51% of patients with depression diagnoses had a VHA visit within 30 days of suicide. A minority of these patients (43%) died by suicide within 30 days of a final visit with mental health services, although 64.5% had received such services within 91 days of their suicide. Among the 57% of patients dying by suicide within 30 days seen in non-mental health settings for their final visit, only 34.1% had a mental health condition coded at the final visit, and only 41.5% were receiving adequate dosages of antidepressant (versus 55.3% last seen by mental health services) (p<0.0005).

Conclusions

VHA patients with depression dying from suicide within 30 days of their final visit received relatively high rates of mental health services, but most final visits still occurred in non-mental health settings. Increased referrals to mental health services, attention to mental health issues in non-mental health settings, and focus on antidepressant treatment adequacy by all providers might have reduced suicide risks for these patients.

Over the past decade, suicide has been increasingly recognized as a major public health problem.1–6 Many studies, primarily from the United Kingdom and Scandinavia, have reported that individuals in the community who died from suicide often have had contact with a health care provider shortly before their death. In their 2002 review, Luoma et al.7 reported that 45% of persons in the general population dying by suicide had had contact with a primary care provider within one month of suicide. In contrast, lower percentages of individuals had had contact with a mental health provider within one month (19%) and one year (32%) of suicide. Thus, most individuals were not receiving mental health treatment at the time of suicide, and many individuals were not known to have a mental disorder until after the suicide.8–10 While it has not yet been conclusively determined to what degree treatment of depression reduces future suicide risk, a recent randomized study indicated that structured depression treatment delivered in primary care settings can reduce suicidal ideation.11 A recent non-randomized study has also indicated that the initiation of either antidepressants or psychotherapy is typically associated with reduced suicide attempts.12 This finding may, however, reflect referral patterns and a general benefit of starting depression treatment, rather than an effect specific to either medications or psychotherapy.12

As a result of these data, many health care systems have introduced programs targeting primary care physicians in an effort to improve their recognition and treatment of psychiatric conditions that increase suicide risks, such as depression.13, 14 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in particular has recently introduced several educational and clinical initiatives designed to improve the detection and treatment of individuals with depressive disorders, in addition to implementing other suicide risk reduction strategies.6 (The VHA is an integrated health care system that treats exclusively veterans and serves approximately 22–23% of U.S. veterans15, 16). Although recognition and treatment of depression is an important early step in suicide prevention, further efforts may be needed to reduce risk of suicide among patients recognized as having depressive disorders. These may include specific quality improvement measures for services provided to depressed individuals across clinical areas (e.g., primary care, specialty mental health care, etc.).17

For this study, we focused on 1843 suicides that occurred in a cohort of all VHA patients who, over a 5.5-year study period, received either: A) more than one diagnosis of depression, or B) the prescription of an antidepressant in addition to a diagnosis of depression. We first determined the percentage of patients with depression who died by suicide who had a clinical encounter shortly before suicide (reasoning that there may be opportunities to intervene and reduce suicide risks at these last, proximal clinical encounters). We then examined 1) whether a recent encounter had occurred with a mental health provider, 2) whether there was a focus on a mental health condition at the time of the final visit, and 3) the adequacy of pharmacologic treatment for depression. To our knowledge, this is the first study to focus on the timing of the last visit before suicide in patients with depressive disorders, and the first to examine these specific indicators of quality of care received by patients with depression shortly before suicide.

Methods

Data Sources

The data for this report was collected from the VHA’s National Registry for Depression (NARDEP),18 maintained by the VHA Serious Mental Illness Treatment Research and Evaluation Center (SMITREC) in Ann Arbor, Michigan. NARDEP includes data from a variety of VA sources for over 2.2 million patients diagnosed with depressive disorders in VA facilities from fiscal year 1997 forward. These data were linked to data from the National Death Index (NDI) (which provides information on all causes of death, including suicide).

Study Design

The observation period for this retrospective cohort study extended from April 1, 1999 to September 30, 2004. Patients were included in the cohort if they had received (1) a diagnosis of a depressive disorder (defined as 296.2x, 296.3x, 298.0, 300.4, 309.0, 309.1, 311, 296.90, 296.99, 293.83, or 301.12) and an antidepressant medication prescription, or (2) a diagnosis of a depressive disorder on two separate days during the study period. We excluded patients with bipolar I, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective diagnoses during the observation period or the year prior to their entry into the cohort since these diagnoses have additional implications for treatment and the risks of suicide.

Study Population

We focused on 1843 cohort members who died by suicide during this time period. This represents approximately 22% of all deaths by suicide among VHA patients for this period. We characterized their final visit prior to suicide by whether they completed their final visit with a mental health provider (as determined by VHA clinic stop codes: 500 series and 690, 692, 693, and 179 or a psychiatric bed section or psychiatric diagnosis as primary inpatient diagnosis), primary care provider (VHA clinic stop codes: 301, 303, 305, 306, 309, 310 312, 323, 322, 312, 348, 350, 531 or 563), emergency room provider (VHA code: 102), or “other” provider. “Other” providers were a diverse, heterogeneous collection of providers including specialist physicians, dental services, audiology services, nurses, social workers, prosthetics providers, preventative care providers, and medical inpatient providers. Telephone encounters were excluded (CPT codes 99371, 99372, and 99373) from study analyses. We reviewed progress notes of all patients who initially appeared to complete suicide the day of their final visit to exclude encounters which were actually documentation of the patients’ death (patients were then assigned their immediately preceding visit as their final visit).

Population Characteristics

We determined demographic and clinical factors associated with the length of time from last visit to died by suicide (0–30 days versus 31+ days from last visit). For patients dying by suicide within 30 days of their last visit, we then determined the association between their demographic and clinical factors and the clinical service seen at last visit. Significance of the relationships between patient demographic and clinical factors and proximity of the last visit to suicide was assessed using chi-square tests.

Potential Indicators of Quality of Care

The “potential quality indicators” we examined were defined as follows:

Existence of a Final Visit Proximal to Suicide

The timing of the last visit relative to the date of suicide was determined.

Recent Treatment from a Mental Health Provider

We determined the proportion of the sample, by service, receiving mental health treatment in the last 91 days.

Focus on Mental Health at the Final Visit

We determined the proportion of the cohort that had any mental health disorder coded at the last visit, as well as the proportion with a mental health disorder coded as the primary diagnosis or as the sole diagnosis. We also determined the proportion receiving a specific diagnosis of depression at the final visit.

Adequacy of Antidepressant Treatment

Using the method of Oquendo et al.,19 antidepressant daily dosages were classified as “adequate” as follows: ≥200 mg of imipramine, amitriptyline, desipramine, trimipramine, clomipramine, maprotiline, doxepin or fluvoxamine; ≥76 mg of nortriptyline; ≥41 mg of protriptyline, selegiline, tranylcypromine or isocarboxazid; ≥ 20 mg of paroxetine, fluoxetine or citalopram; ≥ 100 mg of sertraline; ≥61 mg of phenelzine; ≥300 mg of moclobemide, nefazodone or bupropion; ≥30 mg of mirtazapine; ≥225 mg of venlafaxine; and ≥400 mg of trazodone.

The statistical significance of each quality indicator was tested by chi-square tests.

Results

Existence and Location of a Final Visit Proximal to Suicide

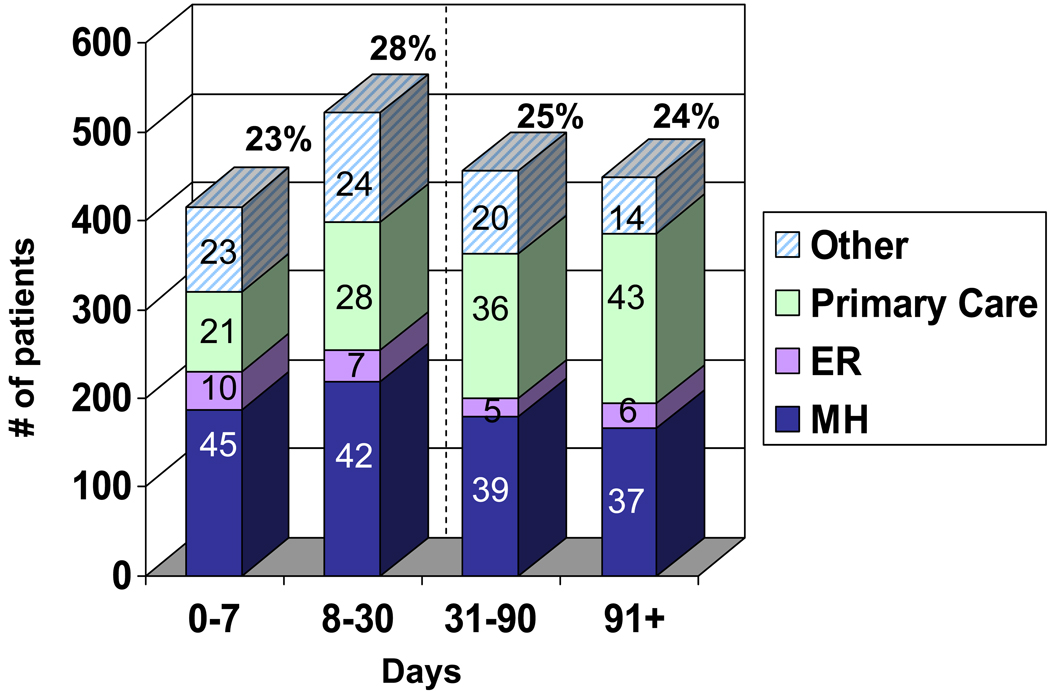

The time interval between the last visit with a VHA provider and died by suicide for patients with diagnosed depression is presented in Figure 1. Just over half (51%) of the patients died by suicide within 30 days of a visit with a VHA provider.

Figure 1. Time from last VHA visit to suicide, by service of last visit.

Percentages in bold above bars indicate percent of total suicides occurring in that time interval from final visit. Numbers inside bars indicate the percentage of suicides in that time period with a final visit with that service. Dotted line indicates time period (0–30 days) from final visit focused upon in subsequent analyses.

Among patients seen within 30 days of suicide, 43% last saw a mental health provider (either as an inpatient or outpatient), 25% last saw a primary care provider, 9% last saw an emergency room provider, and the remaining 23% last saw other providers. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients dying by suicide within 30 days by the last VHA service seen. Patients last seen by mental health were significantly more likely to have had an inpatient stay, and were more likely to have a diagnosis of any depression, major depression or psychotic depression in the 12 months before suicide. Patients last seen by mental health were diagnosed with a larger number of psychiatric disorders on average, and were more likely to have histories of alcohol abuse/dependence, drug abuse/dependence, PTSD, other anxiety disorders, and personality disorders. Patients last seen by non-mental health services were more likely to be older and have more medical conditions. Patients last seen in the emergency room were less likely to be white.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, by service seen at final visit occurring within 30 days of suicide.

| SERVICE SEEN AT LAST VISIT |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics |

TOTAL (N=938) |

Mental Health (n=405) |

Primary Care (n=233) |

Emergency Services (n=80) |

Other (n=220) |

p valuea | |

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||||||

| Male | 97.1(911) | 97.0 (393) | 97.0 (226) | 98.8 (79) | 96.8 (213) | 0.8363 | |

| Age group | 18–39 yrs | 9.2 (86) | 14.3 (58) | 4.7(11) | 8.8 (7) | 4.6 (10) | <.0001 |

| 40–49 yrs | 21.9 (205) | 24.7 (100) | 20.2 (47) | 17.5 (14) | 20.0 (44) | ||

| 50–64 yrs | 36.5 (342) | 39.0(158) | 32.2 (75) | 36.3 (29) | 36.4 (80) | ||

| ≥ 65 yrs | 32.5 (305) | 22.0 (89) | 42.9 (100) | 37.5 (30) | 39.1 (86) | ||

| White Race | 93.9 (803) | 94.2 (341) | 96.7 (206) | 85.1(63) | 93.7(193) | 0.0047 | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 2.9 (27) | 2.7(11) | 3.4 (8) | 2.5 (2) | 2.7 (6) | 0.9496 | |

| Had inpatient Mental Health stay | 34.8 (326) | 50.9 (206) | 18.5 (43) | 27.5 (22) | 25.0 (55) | <.0001 | |

| DIAGNOSES at last visit | |||||||

| Any depressionb | 39.7 (372) | 63.5 (257) | 32.2 (75) | 23.8(19) | 9.6 (21) | <.0001 | |

| Depression NOS | 16.8(158) | 18.3 (13) | 25.8 (60) | 16.3 (13) | 5.0(11) | <.0001 | |

| Major depression | 17.0(159) | 36.3 (147) | 2.2 (5) | 5.0 (4) | 1.4(3) | <.0001 | |

| DIAGNOSES in 12 months before suicide | |||||||

| Any depressionb | 88.6(831) | 95.1(385) | 86.7 (202) | 83.8 (67) | 80.5 (177) | <.0001 | |

| Depression NOS | 65.1(611) | 65.4 (265) | 69.5 (162) | 66.3 (53) | 59.6(131) | 0.1670 | |

| Major depression | 41.7(391) | 61.7 (250) | 21.0 (49) | 32.5 (26) | 30.0 (66) | <.0001 | |

| Psychotic depression | 7.9 (74) | 13.3 (54) | 3.0 (7) | 3.8(3) | 4.6 (10) | <.0001 | |

| Charlson comorbidity indexc | |||||||

| 0 | 45.0 (422) | 56.8 (230) | 38.6 (90) | 45.0 (36) | 30.0 (66) | <.0001 | |

| 1 | 20.9 (196) | 19.3 (78) | 24.5 (57) | 20.0 (16) | 20.5 (45) | ||

| 2 | 10.8 (101) | 8.4 (34) | 12.0 (28) | 13.8 (11) | 12.7 (28) | ||

| > 2 | 23.4 (219) | 15.6 (63) | 24.9 (58) | 21.3 (17) | 36.8 (81) | ||

| DIAGNOSES during or 12 months before cohort entry | |||||||

| Major depression | 25.2 (236) | 38.8 (157) | 12.0 (28) | 13 (16.3) | 17.3 (38) | <.0001 | |

| Drugs or alcohol | 37.2 (349) | 43.7 (177) | 32.2 (75) | 27 (33.8) | 31.8(70) | 0.0047 | |

| Abuse/Dependence | |||||||

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 32.9 (309) | 39.3 (159) | 24.0 (56) | 31.3 (25) | 31.4(69) | 0.0011 | |

| Drug abuse/dependence | 26.0 (244) | 30.4(123) | 20.2 (47) | 23.8(19) | 25.0 (55) | 0.0375 | |

| PTSD | 24.7 (232) | 35.1(142) | 16.7 (39) | 11.3(9) | 19.1(42) | <.0001 | |

| Other anxiety disorder | 37.6 (353) | 43.2(175) | 37.3 (87) | 32.5 (26) | 29.6 (65) | 0.0061 | |

| Psychotic Disorder | 7.4 (69) | 8.4 (34) | 5.2(12) | 10.0 (8) | 6.8 (15) | 0.3591 | |

| MDD with psychosis | 4.8 (45) | 5.9 (24) | 4.3 (10) | 3.8 (3) | 3.6 (8) | 0.5517 | |

| Personality disorder | 10.2 (96) | 16.3 (66) | 4.7(11) | 3.8 (3) | 7.3 (16) | <.0001 | |

| Number of psych dxd | 2–1 | 30.8 (289) | 19.8 (80) | 39.5 (92) | 42.5 (34) | 37.7 (83) | <.0001 |

| 2–3 | 58.7(551) | 63.7 (258) | 54.1 (126) | 51.3(41) | 57.3 (126) | ||

| ≥4 | 10.5 (98) | 16.5 (67) | 6.4(15) | 6.3 (5) | 5.0(11) | ||

2×4, 3×4, or 4×4 Chi-square test as appropriate (2×4: Presence/absence of diagnosis by Service (Mental Health versus Primary Care versus ER versus Other); 3 × 4: (Strata of characteristic (age, number of psych diagnoses) by service (Mental health versus Primary Care versus ER versus Other); 4 × 4: (Strata of characteristic (Charlson comorbidity index) by Service (Mental health versus Primary Care versus ER versus Other).

defined as DSM-IV codes 296.2x, 296.3x, 298.0, 300.4, 309.0, 309.1, 311, 296.90, 296.99, 293.83, or 301.12.

The Charlson Comorbidity Index refers to a weighted index of 19 medical conditions that takes into account the number and seriousness of comorbid medical illness. Conditions included range from cardiac and GI conditions, liver and renal disease, diabetes, COPD, cancers of the blood and solid organs, and AIDS.39

“dx” = diagnoses. Includes any/all depression diagnoses (counts as a single diagnosis), substance dependence/abuse, PTSD, other anxiety disorder, bipolar II, psychotic disorder, and personality disorder.

Tables 2, 3, and 4 examine three potential indicators of the quality/intensity of care received by VHA patients who were last seen within 30 days of their suicide: one focuses on recent treatment by mental health specialty care, and the other two examine treatment at their final visit.

Table 2.

Receipt of Mental Health Specialty Care in the Last 91 Days, by Location of Last Visit

| Timing of Last Mental Health Visit Relative to Suicide |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Mental Health Service Providing Last Visit |

≤91 Days (n=605) % (N) |

≥92 Days (n=192) % (N) |

Never Received Mental Health Specialty Careb (n=141) % (N) |

p valuec |

| Total | 64.5 (605)d | 20.5 (192) | 15.0(141) | NA |

| Primary Care | 33.5 (78) | 34.3 (80) | 32.2 (75) | 0.1135 |

| ER | 38.8(31) | 38.8(31) | 22.5 (18) | |

| Other | 41.4(91) | 36.8(81) | 21.8 (48) | |

For patients completing suicide within 30 days of final visit.

during the study period.

2× 3 (Primary care versus ER versus Other) Chi-square test.

Includes 324 MH Outpatient and 81 MH Inpatient encounters that were the final encounter and occurred within 30 days of suicide, as well as 200 patients whose final visits were with another service but who had had a MH visit in the last 91 days.

Table 3.

Conditions Coded as Treated at Final Visit, by Servicea

| MENTAL HEALTH (MH) DIAGNOSIS (DX) |

Mental Health (n=405) % (N) |

Primary Care (n=233) % (N) |

ER (n=80) % (N) |

Other (n=220) %(N) |

P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any MH Dx | 96.1 (389) | 48.1(112) | 37.5 (30) | 18.2 (40) | <.0001 |

| MH Dx is Primary Dx | 94.3 (382) | 15.9 (37) | 32.5 (26) | 7.3 (16) | <.0001 |

| Any depression | 63.5 (257) | 32.2 (75) | 23.8 (19) | 9.6 (21) | <.0001 |

| Depression NOS | 18.3 (74) | 25.8 (60) | 16.3 (13) | 5.0 (11) | <.0001 |

| Major depression | 36.3 (147) | 2.2 (5) | 5.0 (4) | 1.4 (3) | <.0001 |

For patients completing suicide within 30 days of their final visit.

2×4 (Mental Health versus Primary Care versus ER versus Other) Chi-square test.

Table 4.

Rates of Overall Psychotropic Treatment, Antidepressant Treatment, and Adequate Antidepressant Treatment at last visit, by servicea,b

| SERVICE SEEN AT LAST VISIT |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antidepressant Treatment at last visit |

TOTAL (N=938) % (N) |

Mental Health (n=405) % (N) |

Primary Care (n=233) % (N) |

ER (n=80) % (N) |

Other (n=220) % (N) |

p valuec |

| % receiving ANY Psychotropic | 83.2 (780) | 90.4 (366) | 77.3 (180) | 72.5 (58) | 80.0 (176) | <.0001 |

| % receiving any Antidepressant | 69.9 (656) | 80.3 (325) | 62.2 (145) | 57.5 (46) | 63.6 (140) | <.0001 |

| % Receiving Antidepressant (AD) at Adequate Dose | 47.4 (445) | 55.3 (224) | 41.6 (97) | 41.3 (33) | 41.4 (91) | <.0001 |

| % with current diagnosis of Depression NOS or MDD receiving AD at Adequate Dose | 55.7 (172)d | 58.2 (124)d | 50.8 (33)d | 58.8 (10)d | 35.7 (5)d | 0.1785e |

For patients completing suicide within 30 days of final visit.

Based on dosage in prescription entered for patient at date of last visit, or if no prescription entered that date, the most recent prescription prior to that date.

2×4 (Mental Health versus Primary Care versus ER versus Other) Chi-square test.

Denominators for percent of patients with a current diagnosis of depression not otherwise specified or major depressive disorder receiving adequate doses of antidepressants are n=309 for total, n=213 for mental health, n=65 for primary crae, n=17 for emergency department, and n=14 for other specialties.

The p value for a 2 × 2 chi-squared test (mental health versus all other services combined is .0005.

Recent Treatment from a Mental Health Provider

Table 2 shows that almost two-thirds of patients had seen a mental health provider within the last 91 days (43% of patients had completed their last visits with a specialty mental health provider while an additional 21.5% had completed their last visit with a non-mental health provider but had been seen a mental health provider within the prior three months).

However, 15% of patients had never received specialty mental health care during the study period and 21% received mental health treatment in the last year but not within the last 91 days. Patients whose last visit was with their primary care provider as opposed to other non-mental health services were the least likely to have received recent mental health treatment (33.5%, versus 38.8% and 41.4% for those last seeing ER or other providers, respectively) (χ2=7.3, df=2, p= 0.0262), or to have received any past mental health specialty care during the study period (32.2% never received mental health specialty care, versus 21.8–22.5% seeing ER or other providers) (χ2=7.0, df=2 p=0.0082). Additional analysis indicated that the elderly were at 3X the risk as patients of other ages for not receiving any mental health specialty treatment during the study period (OR=3.3 (2.3–4.8), χ2=44.4, df=1, p<0.0001). Of the patients dying by suicide within 30 days who never had received mental health treatment, 56.7% were ≥ 65 years old (data not shown).

Focus on Mental Health at Final Visit

We sought to determine how likely mental health conditions were a focus of the final visit through examining diagnostic codes recorded at the final visit. Table 3 indicates that, for patients who did not receive their final visit in mental health, little more than one-third of the final visits (34.1%) included coding for any mental health condition compared to 96.1% of mental health final visits (χ2=370.3. df=1, p<0.0001), and only 14.8% had mental health conditions coded as the primary diagnosis (compared with 94.3% of mental health final visits (χ2=582.0, df=1, p<0.0001). Rates of mental health diagnoses at the final visit were highest in primary care, but still were present in less than half of the visits (48.1%). Rates of diagnosis with depression were even lower, particularly major depression.

We examined whether the likelihood of a mental health or depression diagnosis at the final visit was based on whether the patient had received recent (i.e., within 91 days) mental health treatment. Rates of depression diagnoses were lower if a patient was last seen in primary care and had recently received mental health treatment than if they had not recently received mental health treatment (19.2% versus 38.7%, χ2= 9.0, df=1, p<0.0027), and rates of mental health diagnoses were nonsignificantly lower (42.3% versus 51.0%, χ2=1.6, df=1, p<0.21). For the other services, rates were similar regardless of whether patients had received recent mental health services (data not shown).

Even when the final visit was with a mental health provider, only 63.5% of the final visits were coded with a depressive disorder diagnosis despite the fact that this cohort was selected on the basis of having a prior diagnosis of depression (Table 3). We examined the mental health diagnoses received by patients whose last visit within 30 days of suicide was with mental health providers but who did not receive a diagnosis of depression. Four categories of diagnoses made up approximately 84% of the diagnoses among those not receiving a depression diagnosis: adjustment disorders (33.8%), alcohol dependence (20.8%), drug abuse or dependence (15.6%), and anxiety disorders (13.6%) (data not shown).

Adequacy of Antidepressant Treatment

Table 4 indicates that less than half of those dying by suicide within 30 days of the last visit were receiving antidepressant at adequate dosage (47.4%) at the date of the final visit. This percentage increased for those patients with their last visit in mental health (55.3%) versus other settings (41.3–41.6%) (χ2=17.7, df=3, p<0.0005). A major determinant of these relatively low rates of adequate antidepressant treatment appears to be the substantial fraction of individuals receiving no antidepressant treatment (from 19.7% receiving a mental health final visit to 42.5% receiving an ER final visit). When we limited our analysis to patients seeing a non-mental health provider at final visit, we observed adequate antidepressant treatment significantly higher for patients receiving recent mental health specialty care (52.0% versus 35.1%, χ2=14.6, df=1, p =0.0001) (data not shown).

We also restricted our analysis to individuals who received specific depression diagnoses (Depression NOS or Major Depressive Disorder) the day of their final visit to examine whether one possible reason for the low rates of adequate antidepressant treatment is that some individuals were no longer considered depressed. Rates of adequate depression treatment did increase modestly to 55.7%, were no longer statistically differed between services (χ2=3.5, df=3, p<0.3182), and were numerically similar (ranging from 50.8–58.8%), except for other providers (35.7%).

As a subgroup analysis, we examined individuals dying of suicide within 7 days of their final visit (416 patients). We observed generally similar patterns of care to that received by individuals dying of suicide within 30 days of their final visit. Rates of mental health specialty care utilization were similar (65.8% had had mental health specialty visits in the last 91 days, 20% had seen mental health providers, but not within the last 91 days, and 14.1% had not seen mental health providers during the study period). The proportion of individuals whose final visit was with inpatient mental health services was also similar (8.6% for those dying by suicide within 30 days, 10.1% for those dying by suicide within 7 days). A similar pattern across services in the prevalence of final visit psychiatric diagnoses was observed: a 96% rate of psychiatric diagnoses for final mental health visits, 46% rate for primary care, 40% for ER visits, and 23% for visits with other providers,(χ2=176.5, df=3, p<0.0001). Individuals dying of suicide within 7 days of their final visit had experienced higher rates of antidepressant adequacy, although the pattern of antidepressant adequacy across services was similar: 82% of patients last seen by mental health providers had adequate antidepressant treatment, followed by 64% of patients last seen by other providers, 63% of those last seen by primary care, and 56% of those last seen by ER providers (χ2=21.8, df=3, p<0.0001).

Discussion

Our study indicated that approximately half (51%) of VHA patients with depression dying by suicide from 1999–2004 saw a health care provider in the month before suicide. Given the proximity of these final visits to death from suicide, we assumed that many of these patients may have been experiencing substantial depression symptoms and possibly suicidal ideation at the time of this final visit. We focused our subsequent analyses of potential quality indicators on these patients dying by suicide within 30 days of their final VHA visit.

Many patients dying by suicide within 30 days of their final visit saw a mental health provider for either their final visit (43%) or within the 3 months prior to suicide (64.5 %). Despite this fact, adequate antidepressant treatment was only incompletely provided (45% of patients last seeing a mental health provider and 58% of patients seeing other services were not receiving adequate doses of antidepressants). Furthermore, as others have observed,20 if a patient was not seen by a mental health provider for their final visit, psychiatric diagnoses were usually not recorded, suggesting that mental health issues were usually not a focus of the final visit. This is particularly concerning since, despite the high level of engagement of patients with identified depressive disorders with mental health specialty care, the majority saw a non-mental health provider at their final visit. Primary care, the emergency room, and other services remain “on the front lines” of caring for suicidal individuals, even for those receiving mental health specialty care.

Our data suggests that when patients with depressive disorders receive their last visit outside of mental health or the emergency room, their mental health conditions are often not the focus of the meeting. While it may not be realistic to expect non-mental health clinicians, trained to attend to myriad physical conditions, to routinely devote encounters substantially to mental health, patients with diagnosed depressive disorders may need more careful screening and attention.

Non-mental health clinicians may also pay less attention to mental health conditions when patients are also seen in mental health care, potentially feeling that these issues are addressed elsewhere. We found that patients last seen in primary care were significantly less likely to receive a diagnosis of depression at their final visit, and nonsignificantly less likely to receive a diagnosis of any psychiatric disorder, if they were receiving recent mental health treatment. The extent to which exacerbations of depression may be being missed in these patients because it is assumed their conditions are being addressed elsewhere is unclear.

Our data, similar to previous reports,8, 21, 22 also suggest that there may be additional room for referral to mental health care. This may be especially true for elderly patients: many elders who die from suicide proximal to VHA appointments were never seen in mental health care. This observation is similar to recent findings from Taiwan that men >55 years old were the least likely to use a MH provider in the year before suicide,21 and to older findings from Finland.22

The causes of lower use of mental health services by the elderly, in the VHA and in general, are likely multifactorial. Studies have indicated that many elderly patients may prefer to receive mental health services in a primary care setting rather than from specialty mental health services.23, 24 These findings have been part of the rationale for the VHA and other health systems to provide more mental health care integrated into primary care settings. However, our study indicates that many elderly patients with depression completing suicide shortly after a visit were being seen in primary care and did not receive a diagnosis of depression or any other mental health condition at their final visit. Higher levels of referral to mental health services may be desirable for elderly patients that are willing to accept such referrals, along with further improvement of primary care services for patients who elect to remain in primary care. The VHA’s integrated health care system facilitates such referrals, which may not be as easily achieved in more fragmented health systems or those limiting mental health specialty care access. The importance of adequate treatment of geriatric depression has been underscored by the recent FDA metaanalysis of adult antidepressant trials, which found the elderly to be the only group with a statistically significant decrease in risk of completed suicide with antidepressant treatment.25

Although speculative, it is possible that primary care providers may not be factoring in the increased lethality of late-life depression10 when deciding whether to refer, or may not realize that the increased number of medical conditions requiring management in elderly patients may make it more difficult for PCPs to also adequately manage mental health conditions.26 In addition, it is possible that providers may be slower to recognize or more apt to discount suicidality in patients they have treated for a long period of time. It is worth noting that, among patients diagnosed with depression, almost 70% of suicide deaths occurring within 30 days of a health care visit occurred in individuals 50 years and older, and 32.5% in patients 65 years and older.

We found that less than half of our cohort was receiving antidepressants at adequate dose at last visit. Even when we restricted the sample to those clearly having a current diagnosis of depression at their last visit, almost half of our cohort (44 %) still was not receiving adequate doses of antidepressant. While these rates easily exceed rates of toxicologically confirmed antidepressant use among suicide deaths from general population samples27–32 and from psychological autopsies of samples with depression treated with older (pre-SSRI) antidepressants33 or samples with likely mental illness,34 the fact that approximately 1/2 of patients with diagnosed depression seen proximal to their suicide were not receiving adequate doses of antidepressants suggests a potential target for quality improvement efforts.

Limitations of our study included the fact that our methodology relied on routinely recorded administrative data which did not permit the addressing of the adequacy of suicidal assessment that patients received in their final visit. As other reports have found, suicide assessments may have been conducted, and the patient may not have communicated suicidal intent.35, 36 This might occur either because patients were not yet suicidal, were unaware of, discounted, or concealed their suicidal vulnerability, or were judged by the clinician not to be at high suicide risk. Thus, it cannot be inferred that clinicians in our study failed to complete these assessments without chart reviews. Second, for our analysis of the prevalence of coding of mental health conditions at the final visit, it is possible providers may actually address mental health conditions more frequently than reflected in diagnostic codes (e.g., if providers were concerned about stigmatizing the patient). All patients in our cohort had already received at least one coded diagnosis of depression, however. Third, antidepressant usage could partly qualify patients for entry into the cohort (in conjunction with at least one diagnosis of depression), possibly resulting in higher rates of antidepressant treatment than if our definition had exclusively used diagnostic codes. Fourth, because of our focus on the VHA system of care, we are not able to determine if veterans may have used non-VHA emergency rooms, inpatient mental health units, or outpatient providers before suicide: the data given here are for the VHA system only. In addition, while our sample was a comprehensive subset of VHA patients, such patients are not representative of the entire veteran population or of patients in other settings of care. (For example, only approximately 22–23% of all veterans use VHA health facilities15, 16). Thus, the generalizability of our findings to more demographically (e.g., gender and racial/ethnic) or occupationally (e.g., non-veteran) diverse populations and other healthcare systems cannot be determined. Lastly, this investigation’s study period ends shortly before the initiation of several VHA suicide prevention initiatives (e.g., increased screening in primary care, flagging of high risk patients, etc.), which may have influenced the patterns reported here.

Strengths of our study include a nationwide sample receiving care over 5+ years that is sufficiently large (1843 suicide deaths, 938 within 30 days of final visit) to allow temporal and treatment patterns to be evaluated. In addition, the VHA databases allow linking of diagnostic, treatment, and demographic information, as well as linkages between inpatient and outpatient care.

To put our results concerning the timing of visits prior to suicide into context, it is helpful to match the approach of other published reports7 which examined the timing of care received by the entire cohort dying of suicide. Examining the entire cohort of 1843 patients with depression dying by suicide, 27.1% of patients had seen a mental health provider within 30 days of suicide and 65.4% within a year. Not surprisingly, this rate of mental health specialty care contact compares extremely favorably with the rates reported by Luoma et al.7 for general samples of patients who died from suicide (i.e., those with any diagnosis). Luoma et al.7 reported that on average 19 % of patients saw a mental healthcare provider within 30 days of suicide (range 7–28%), and 32% saw a mental healthcare provider within 1 year (16%– 46%). Thus substantially more of our cohort (64.5% versus 46%) received mental health specialty care than for any of the general samples treated in other health care systems as reported by Luoma et al.7 However, higher rates of mental health specialty care are expected for a cohort with identified depression: further research is needed to determine the VHA’s performance compared to samples from other healthcare systems in treating individuals with depressive disorders who die from suicide.

We found few parallels in the literature for the main focus of our study, which not only characterized timing of final visits, but examined aspects of the quality of care patients received shortly before suicide to find targets for care improvement. The findings of this report suggest several areas for quality improvement in the quest to identify and treat suicidal behavior among depressed patients:

For specialty mental health providers, there is a clear need to ensure that patients with depression are receiving adequate dosage of antidepressant medication. In addition, it appears important to exercise care in deciding which patients in active mental health care are terminated from mental health specialty care or allowed to transition to low utilization of the service (20.5% of the sample dying by suicide within 30 days of their final visit had received previous mental health care, but not in the last 3 months). Care should be exercised to continue to attend to suicide risk if diagnoses are revised to nondepressive diagnoses. Finally, it is clear that mental health visits are often the final encounters of high risk patients with the VHA system, creating a need for systems, researchers, and providers to continue to examine how to provide more effective care in such sessions to help prevent suicide.

For non-mental health providers, several important issues emerge from our data, especially the need to continue to remain vigilant to suicidal crises or increases in suicidal risk even if a patient is receiving mental health specialty care. This may be challenging, especially when other, non-psychiatric conditions are competing for attention.26 For this reason, a low threshold to refer patients potentially at suicide risk to mental health specialty care might be considered, along with encouraging referrals of elderly patients with depression in general who will accept mental health specialty care referral. We found more than half the patients dying by suicide without any previous mental health specialty care during our study period were elderly.

If efforts were made to implement and systematically follow up on treatment strategies that emphasized adequate doses of antidepressants (e.g., through use of the PHQ-9, which includes a suicide item) then this single intervention might dually address the low rates of adequate treatment and the need to periodically monitor the intensity of depression and suicidality in depressed patients. Systems might also consider identifying and alerting providers of high risk patients through high risk chart flags and the routine query of family members37, 38 for possible suicide clues. The VHA has begun initiatives in several of these areas.

In conclusion, among this large sample of patients with depressive disorders who died by suicide within 30 days of their final visit, we found that most patients had their last visit in non-mental health settings, 2) mental health conditions were infrequently a focus of their final visits in non-mental health settings, 3), many patients had inadequate antidepressant treatment, and 4) the elderly were disproportionately represented among those never seen in mental health specialty care. These data, potentially obtainable from administrative data from other healthcare systems as well, can inform future efforts to reduce suicide risks among patients with identified depressive disorders.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Department of Veterans Affairs IIR 04-211 and National Institute of Mental Health R01 MH078698 and by the Serious Mental Illness Treatment Research and Evaluation Center, Ann Arbor, MI.

Footnotes

Elements of this manuscript were presented at the 2009 Veteran’s Affairs Health Services Research and Development Annual Meeting.

Disclaimer: Dr. Smith is supported in part through VHA Health Services Research and Development Center of Excellence Funding to the Center for Health Quality, Outcomes, and Economic Research, Bedford, Massachusetts. He also receives grant funding from the Forest Research Institute, an affiliate of Forest Labs, Incorporated, an antidepressant manufacturer, for unrelated investigator-initiated research. Dr. Valenstein and Ms. Ganoczy receive funding from the Department of Veteran Affairs but have no financial interests to disclose. Dr. Craig and Ms. Walters have no funding or financial interests to disclose.

References

- 1.United States. Public Health Service. Washington, D.C.: Dept. of Health and Human Services, U.S. Public Health Service; Office of the Surgeon General, The Surgeon General's call to action to prevent suicide, 1999. 1999

- 2.Knox KL, Conwell Y, Caine ED. If suicide is a public health problem, what are we doing to prevent it? Am J Public Health. 2004;94(1):37–45. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knox KL, Caine ED. Establishing priorities for reducing suicide and its antecedents in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(11):1898–1903. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. Jama. 2005;294(16):2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldsmith SK. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Pathophysiology & Prevention of Adolescent & Adult Suicide., Reducing suicide: a national imperative. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Inspector General, Healthcare Inspection: Implementing VHA's Mental Health Strategic Plan Initiatives for Suicide Prevention. VA OIG Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(6):909–916. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owens C, Lloyd KR, Campbell J. Access to health care prior to suicide: findings from a psychological autopsy study. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(501):279–281. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owens C, Booth N, Briscoe M, et al. Suicide outside the care of mental health services: a case-controlled psychological autopsy study. Crisis. 2003;24(3):113–121. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.24.3.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Cox C, et al. Relationships of age and axis I diagnoses in victims of completed suicide: a psychological autopsy study. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(8):1001–1008. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.8.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Katz II, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, Brown GK, McAvay GJ, Pearson JL, Alexopoulos GS. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(9):1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon GE, Savarino J. Suicide attempts among patients starting depression treatment with medications or psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7):1029–1034. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobscha SK, Gerrity MS, Ward MF. Effectiveness of an intervention to improve primary care provider recognition of depression. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4(4):163–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearson JL, Conwell Y, Lyness JM. Late-life suicide and depression in the primary care setting. New Dir Ment Health Serv. 1997;(76):13–38. doi: 10.1002/yd.2330247604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department of Veterans Affairs. National Survey of Veterans. [Accessed October 1 2009];Final Report. :6–12–6–13. http://www1.va.gov/vetdata/docs/NSV%20Final%20Report.pdf.

- 16.Nugent G, Hendricks A. Estimating Private Sector Values for VA Health Care. An Overview. Medical Care. vol. 41(no. 6) supplement:II-2–II-10. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000068379.03474.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams JW, Jr, Rost K, Dietrich AJ, et al. Primary care physicians' approach to depressive disorders. Effects of physician specialty and practice structure. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8(1):58–67. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blow FC, Valenstein M, Austin K, Khanuja K, McCarthy JF. Specialty Care for Veterans with Depression in the VHA: 2002 National Depression Registry Report. 2003. [Accessed July 23, 2009];Ann Arbor, MI: VA National Serious Mental Illness Treatment Research & Evaluation Center (SMITREC), VHA Health Services Research & Development. Available at: http://www.hsrd.ann-arbor.med.va.gov/documents/2002NARDEP.pdf.

- 19.Oquendo MA, Baca-Garcia E, Kartachov A, et al. A computer algorithm for calculating the adequacy of antidepressant treatment in unipolar and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(7):825–833. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan YJ, Lee MB, Chiang HC, et al. The recognition of diagnosable psychiatric disorders in suicide cases' last medical contacts. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(2):181–184. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee HC, Lin HC, Liu TC, et al. Contact of mental and nonmental health care providers prior to suicide in Taiwan: a population-based study. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53(6):377–383. doi: 10.1177/070674370805300607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pitkala K, Isometsa ET, Henriksson MM, et al. Elderly suicide in Finland. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12(2):209–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klap R, Unroe KT, Unützer J. Caring for mental illness in the United States: a focus on older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(5):517–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartels SJ, Coakley EH, Zubritsky C, Ware JH, Miles KM, Areán PA, Chen H, Oslin DW, Llorente MD, Costantino G, Quijano L, McIntyre JS, Linkins KW, Oxman TE, Maxwell J, Levkoff SE. PRISM-E Investigators. Improving access to geriatric mental health services: a randomized trial comparing treatment engagement with integrated versus enhanced referral care for depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(8):1455–1462. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone M, Laughren T, Jones ML, Levenson M, Holland PC, Hughes A, Hammad TA, Temple R, Rochester G. Risk of suicidality in clinical trials of antidepressants in adults: analysis of proprietary data submitted to US Food and Drug Administration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2880. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harwood DM, Hawton K, Hope T, et al. Suicide in older people: mode of death, demographic factors, and medical contact before death. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(8):736–743. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200008)15:8<736::aid-gps214>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rich CL, Isacsson G. Suicide and antidepressants in south Alabama: evidence for improved treatment of depression. J Affect Disord. 1997;45(3):135–142. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isacsson G, Holmgren P, Wasserman D, et al. Use of antidepressants among people committing suicide in Sweden. Bmj. 1994;308(6927):506–509. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6927.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isacsson G, Holmgren P, Druid H, et al. Psychotropics and suicide prevention. Implications from toxicological screening of 5281 suicides in Sweden 1992–1994. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:259–265. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isacsson G, Boethius G, Bergman U. Low level of antidepressant prescription for people who later commit suicide: 15 years of experience from a population-based drug database in Sweden. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;85(6):444–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb03209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Isacsson G, Bergman U, Rich CL. Antidepressants, depression and suicide: an analysis of the San Diego study. J Affect Disord. 1994;32(4):277–286. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henriksson S, Boethius G, Isacsson G. Suicides are seldom prescribed antidepressants: findings from a prospective prescription database in Jamtland county, Sweden, 1985–95. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103(4):301–306. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isometsa ET, Henriksson MM, Aro HM, et al. Suicide in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(4):530–536. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.4.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller CL, Druss B. Datapoints: suicide and access to care. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(12):1566. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isometsa ET, Heikkinen ME, Marttunen MJ, et al. The last appointment before suicide: is suicide intent communicated? Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(6):919–922. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.6.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Earle KA, Forquer SL, Volo AM, et al. Characteristics of outpatient suicides. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(2):123–126. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Draper B, Snowdon J, Wyder M. A pilot study of the suicide victim's last contact with a health professional. Crisis. 2008;29(2):96–101. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.29.2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Owens C, Lambert H, Donovan J, et al. A qualitative study of help seeking and primary care consultation prior to suicide. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(516):503–509. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charlson ME, Pompeii P, Ales KL, Mackenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]