Abstract

Few studies have assessed changes in alcohol use before and after a massive disaster. We investigated the contribution of exposure to traumatic events and stressors related to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita to alcohol use and binge drinking. We used data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics collected in Mississippi, Louisiana and Alabama on adults aged 18–85 (n=439): 1) data from 1968–2005 on household income; 2) data from 2005 and 2007 on total number of drinks per year and number of days the respondent binged; and 3) data from 2007 on exposure to hurricane-related traumatic events and post-hurricane stressors. Exposure to each additional hurricane-related traumatic event was associated with 79.2 more drinks and 2.46 times higher odds of binge drinking for more days in the past year (95% CI: 1.09, 5.55), while more post-disaster stressors were associated with 16.5 more drinks and 1.23 times higher odds of binge drinking for more days in the past year (95% CI: 0.99, 1.51). Respondents who had followed a lower lifetime income trajectory and were exposed to more lifetime traumatic events experienced the highest risk of reporting increased alcohol use given exposure to hurricane-related traumatic events and post-hurricane stressors. Disaster-related traumatic events and the proliferation of post-disaster stressors may result in increased post-disaster alcohol use and abuse. Disaster-related exposures may have a particularly strong impact among individuals with a history of social and economic adversity, widening preexisting health disparities.

Keywords: disasters, traumatic events, health disparities, alcohol use

1. Introduction

Hurricanes Katrina and Rita had the greatest impact on mortality and economic damage of any natural disaster that hit the United States in the past 75 years. The extent of destruction resulting from Hurricanes Katrina/Rita, including the death of more than 1000 people, the displacement of 500,000 others and more than $100 billion in damage, would lead us to expect a high prevalence of mental health problems among those exposed to Katrina/Rita (Rosenbaum, 2006).

While many studies exist on the relationship between natural disasters and alcohol use (Cepeda A. et al., 2010; North et al., 2004; Reijneveld et al., 2005), few have investigated the impact of specific aspects of a disaster on alcohol consumption. Two studies have found a link between disaster-related posttraumatic stress symptoms and alcohol use (Green et al., 1985; Schroeder and Polusny, 2004). Such evidence, paired with evidence of a link between exposure to traumatic events in other settings and alcohol use (Stewart, 1996) indicate a plausible connection between the traumatic consequences of a disaster and alcohol use and abuse. A few studies have also found a link between post-disaster life stressors and alcohol use (Rohrbach et al., 2009) and other types of psychological problems (Galea et al., 2007; Galea et al., 2008; Peek et al., 2008). Post-disaster stressors may magnify the distress induced by a disaster, and may contribute to the use of alcohol as a way to self-medicate symptoms of stress (Aseltine et al., 1998; Newcomb et al., 1999).

Although degree of disaster-related exposure is clearly central to the determination of post-disaster behavioral pathology, individual social and economic resources before and after a disaster may modify the relation between disaster-related experiences and their consequences (Browning et al., 2006; Galea and Hadley, 2006; Kar et al., 2007; Seplaki et al., 2006). Persons with more social and economic resources may be more likely to avoid experiencing disaster-related events, by heeding advance warnings and evacuating or by being located in safer housing (Finch et al., 2010), and may be more likely to retain resources after an event that may be critical in facilitating post-disaster recovery. Following Hobfoll’s Conservation of Resources Theory (Hobfoll, 2001), those with greater initial reserves of resources are less vulnerable to resource loss and more capable of mobilizing resources to “bounce back” in the event of a source of traumatic stress such as a disaster. Conversely, those of lower socioeconomic status may be more vulnerable to the adverse effects of disasters because of greater proportionate losses to property and finances, and more difficult recoveries marked by greater exposure to adverse living conditions (Fothergill and Peek, 2004). In addition, following the perspective of “cumulative adversity” (Lloyd and Turner, 2008; Turner and Lloyd, 1995; Turner and Lloyd, 2003), distal (e.g. lifetime experiences of economic disadvantage or traumatic events) and proximal (e.g. exposure to a natural disaster) stress exposures accumulate over the lifecourse and predict a greater vulnerability to alcohol abuse than either type of stress exposure alone.

Many of the persons most affected by Hurricanes Katrina/Rita in the short term were minorities and persons of lower socioeconomic status (SES) (Coker, 2006; Rodriguez and al., 2006). These groups already had worse health before Hurricanes Katrina/Rita than other, more advantaged groups. If the hurricanes did indeed affect disadvantaged groups more than advantaged groups it is likely that Hurricanes Katrina/Rita contributed to a further worsening of health indicators among these persons, widening health disparities in the Gulf Coast region. These widening racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in specific health indicators may have important long-term implications for population health in the Gulf Coast regions for years to come.

Alternately, individuals exposed to moderate economic or social stress may actually be better able to cope with the stress generated by a massive disaster. The challenge model of resilience (Fergus and Zimmerman, 2005) posits that moderate levels of risk are actually associated with positive outcomes. Specifically, continuous or repeated exposure to moderate levels of a risk factor may help individuals mobilize assets so that they are better prepared to overcome adversity (such as a disaster) in the future, and less vulnerable to using alcohol to reduce disaster-related stress.

Current studies on the health impact of massive disasters are limited in several ways. First, we are aware of only three other prospective studies on the relationship between exposure to a disaster and alcohol use (Hasin et al., 2007; Richman et al., 2009; Rohrbach et al., 2009), and of these, only one (Rohrbach et al., 2009) focused on the impact of a natural disaster on alcohol use. Second, many have focused on select populations (CDC, 2006b; Coker, 2006; Rodriguez and al., 2006), such as those recruited from shelters and evacuation centers (CDC, 2006c; Coker, 2006; Rodriguez and al., 2006) or professionals involved in the rescue effort (CDC, 2006b). Finally, due to the difficulties involved in tracing people exposed to a disaster, studies often include very small samples (CDC, 2006a).

In this paper, we therefore build on prior research in two ways: (1) we have pre- and post-hurricane measures on level of alcohol use, so that we can examine the impact of exposure to disaster-related traumatic events and post-disaster stressors on change in alcohol use; and (2) we have prospectively-collected measures on respondent lifetime income trajectories, so that we can investigate how long-term income histories shape the relationship between exposure to disaster-related traumatic events and post-disaster stressors and alcohol use. We examined the range of alcohol use and abuse, including: (1) level of alcohol consumption from no use to regular high levels of consumption; and (2) frequency of binge drinking in the past year.

2. Methods

2.1 Sample

The PSID is a nationally representative sample of what were originally 5000 families first interviewed in 1968 (Hill, 1992). It consisted of two sub-samples: a national sample of 3000 families taken from all areas, and a national sample of 2000 families living in low-income counties. The initial response rate for the entire PSID sample in 1968 was 76%, in 1969 it was 88.5%, and since then it has been 96.9–98.5%. The PSID sample, with appropriate weights, constituted a national sample of the US population with an over-sample of poor families. Interviews were conducted annually from 1968–1997 and biannually since 1997. In 2007, persons living in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama before Hurricanes Katrina/Rita and who responded to the 2005 PSID survey were recontacted and received a 20-minute survey designed to assess exposure to the hurricanes and mental health status, in addition to the PSID standard survey (n=555). Persons who had moved to other areas as a result of the hurricanes were tracked to their new addresses by using contact persons supplied by the participants during the 2005 PSID survey, the US Postal Service National Change of Address Service, and Red Cross and similar websites set up to identify relocated disaster victims. In 2007, the PSID had a 97% wave-to-wave reinterview rate, and the Katrina/Rita module had a 96% response rate.

The PSID questions were asked to a “respondent” in the household, who answered on behalf of the head of the household and his/her partner, and was not necessarily the head or partner. In order to be included in our study, study participants needed to have been: 1) the head of household or the partner in both 2005 and 2007; and 2) the respondent in both 2005 and 2007 (n=439). We removed those participants who had responded in either year through a proxy, as proxy reports of alcohol use could suffer from misclassification and the questions about Katrina/Rita were addressed directly to the respondent.

We used two types of data for this study: 1) data from the PSID from 1968–2005 to measure income trajectories, alcohol consumption levels and binge drinking frequency before Hurricanes Katrina/Rita (in 2005), and 2) data from the 2007 survey to measure exposure to Hurricanes Katrina/Rita and post-event alcohol consumption and binge drinking. Our analytic sample is thus not the national PSID sample, but those PSID respondents who lived in the Gulf Coast region in 2005.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Alcohol consumption

Level of alcohol consumption was measured in 2005 and 2007 as the number of drinks per day times the frequency of consumption in the past year (6-category response option, ranging from “less than once a month” to “every day”). We also constructed an ordinal measure of binge drinking, or the number of occasions the respondent had 4/5 drinks in one sitting in the past year (4 category option, ranging from “never” to “three or more times”) in 2005 and 2007.

2.2.2 Exposure to Hurricanes Katrina/Rita and prior traumatic events

We assessed experiences during Hurricanes Katrina/Rita using the 2007 Hurricane Katrina PSID Supplement. We examined: 1) exposure to a count of traumatic events during the hurricanes (including whether the respondent was physically injured, knew someone who was injured or killed, or saw dead bodies); 2) any property damage or loss as a result of the hurricane (reported “a lot” of damage to property or possessions, lost sentimental possessions like photographs); and 3) exposure to a count of stressors in the six months after the hurricane (including shortage of food or water, unsanitary conditions, fear of crime, feelings of isolation, and loss of electricity, Cronbach’s α = .80). These items were modified from scales used in prior studies of natural disasters (Galea et al., 2008).

The Crisis Support Scale (Joseph et al., 1992) was used to measure social support in the 2 months after Hurricanes Katrina/Rita; items were summed for a total social support score ranging from 0 to 42 (Cronbach’s α = .83), which was categorized into tertiles.

Information about lifetime traumatic events experienced by respondents prior to Hurricanes Katrina/Rita was collected using a modified version of Criterion A traumatic events from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Kessler and Üstün, 2004). The number of traumatic events experienced prior to Hurricanes Katrina/Rita was categorized into low (0–1), medium (2–3), and high (4 or more).

2.2.3 Sociodemographic characteristics

Respondent lifetime taxable and transfer household income, adjusted for inflation to 2003 using the Consumer Price Index, was assessed from 1968 to 2005. Gender; age (18–30, 31–40, 41–50, >50); race/ethnicity (white, black, other); marital status (never married, widowed/separated/divorced, married); years of education (<high school, high school or equivalent, >high school); home ownership status; and family size were measured as of 2005.

2.3 Analyses

We conducted two types of analyses: 1) to estimate the types of income trajectories respondents followed from 1968–2005; and 2) to estimate the relationship between exposure to Hurricanes Katrina/Rita and alcohol consumption.

2.3.1 Income trajectories

We used semi-parametric group-based modeling (Nagin, 2005) to identify the number of lifetime household income patterns respondents followed. These models were determined based on income data that was available in 1968–2005 for the respondents’ household during the time the respondent was alive.

Rather than capturing variability in trajectories through a random coefficient like traditional growth curve models do, group-based models assume that the sample is composed of a mixture of underlying trajectory groups, each defined by an average growth curve (Wiesner et al., 2007). Using PROC TRAJ in SAS, we estimated cubic polynomial censored normal models of log adjusted household income. We fit separate models with two to five trajectory groups, due to sample size restrictions, and used the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to select the best-fitting model. We then determined the optimal number of parameters to define the shape of each trajectory group (i.e. linear, quadratic, cubic) by their significance (p<0.05). All group-based models are unconditional, since we used them merely to classify individuals into different income trajectories.

2.3.2 Alcohol use

We first described the characteristics of the overall sample in order to describe level of exposure to Hurricanes Katrina/Rita, including direct exposure to the hurricane, to traumatic events during the hurricane, property damage or loss related to the hurricane, and to post-hurricane stressors. We fit a series of linear regression models to estimate the magnitude of change in level of consumption between 2005 and 2007, adjusting for baseline alcohol use. We used cumulative logit regression models to estimate the odds of reported binge drinking on a higher number of days in 2007, controlling for the reported frequency of binge drinking in 2005. We used the same modeling strategy for the two outcomes: first, we estimated separate models for three aspects of hurricane exposure (traumatic events, property damage/loss, post-hurricane stressors), controlling for pre-hurricane sociodemographic characteristics and lifetime traumatic events (Models 1–3), then we incorporated post-hurricane social support as an additional covariate, including those aspects of hurricane exposure that were significant predictors in previous models (Model 4). For aspects of hurricane exposure that were significant predictors in previous models, we also investigated whether interactions existed with income group trajectory membership and lifetime traumatic events. Only those interactions that were statistically significant (p<0.05) are presented as figures; tables for all interactions are available in the electronic supplement. All analyses were conducted using R (R Development Core Team, 2010).

3. Results

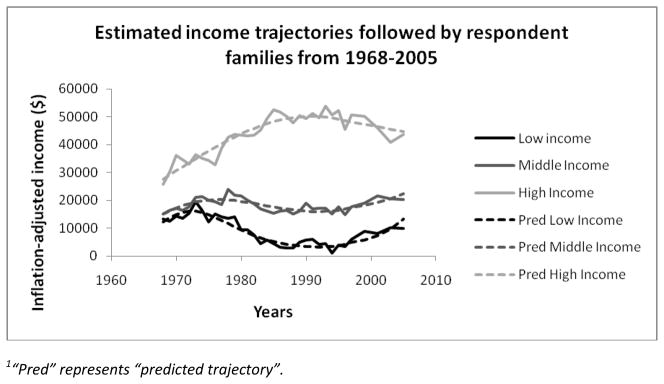

Table 1 presents unweighted and weighted estimates of the socio-demographic characteristics of the PSID sample who lived in the Gulf Coast areas affected by Hurricanes Katrina/Rita in 2005. The sample consisted of adults aged 18 to 85 (average age 41.4 years), with a lower representation of males (35.9% of sample) than females. 24.4% of respondents were White and 27.1% were African-American. As shown in Figure 1, a three-group trajectory model provided the best fit for the lifetime household income data for the study respondents. The largest group (51.4% of the sample) consisted of respondents whose income ranged from an average of $15,167 in 1968 to $20,404 in 2005 (“middle income group”). The second-largest group (33.3% of sample) exhibited relatively higher levels of income, ranging from $25,712 in 1968 to a peak of $50,138 in 1991 (“high income group”). The smallest group (15.3% of sample) exhibited consistently low levels of income, ranging from $13,402 in 1968 and dropping to a low of $3,350 in 1991 (“low income group”).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics and alcohol consumption of PSID respondents who resided in the areas of Gulf Coast that were affected by Hurricane Katrina/Rita (n=439)*

| Characteristic | Unweighted | Weighted | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % or mean (SD) | % or mean (SD) | |

| Total number of drinks in past year (mean, SD) | |||

| Total number of drinks in 2005 | - | 113.2 (439.2) | 145.2 (1520.1) |

| Total number of drinks in 2007 | - | 90.3 (378.6) | 114.3 (1292.4) |

| Binge drinking in the past year, 2005 | |||

| Never binged in the past year | 350 | 81.2 | 77.9 |

| Binged once in the past year | 16 | 3.7 | 1.8 |

| Binged twice in the past year | 15 | 3.5 | 7.7 |

| Binged three or more times in the past year | 50 | 11.6 | 12.7 |

| Binge drinking in the past year, 2007 | |||

| Never binged in the past year | 362 | 83.4 | 81.8 |

| Binged once in the past year | 12 | 2.8 | 4.0 |

| Binged twice in the past year | 20 | 4.6 | 3.9 |

| Binged three or more times in the past year | 40 | 9.2 | 10.3 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 122 | 27.8 | 35.9 |

| Female | 317 | 72.2 | 64.1 |

| Age | |||

| 18–30 | 127 | 28.9 | 17.9 |

| 31–40 | 90 | 20.5 | 19.9 |

| 41–50 | 109 | 24.8 | 24.8 |

| >50 | 113 | 25.7 | 37.4 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 62 | 15.1 | 24.4 |

| Black | 201 | 48.8 | 27.1 |

| Other | 149 | 36.2 | 48.6 |

| Educational attainment | |||

| <High school | 81 | 19.5 | 14.8 |

| High school or equivalent | 166 | 40.0 | 39.1 |

| >High school | 168 | 40.5 | 46.1 |

| Household income trajectory, 1968–2005 | |||

| Low income group | 49 | 11.2 | 15.3 |

| Middle income group | 233 | 53.1 | 51.4 |

| High income group | 157 | 35.8 | 33.3 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 180 | 41.0 | 48.4 |

| Divorced, widowed or separated | 133 | 30.3 | 22.3 |

| Never been married | 126 | 28.7 | 29.4 |

| Home ownership | |||

| Owned home | 251 | 60.9 | 71.6 |

| Family size | |||

| 1 person | 93 | 21.2 | 26.6 |

| 2 people | 102 | 23.2 | 31.8 |

| 3 people | 119 | 27.1 | 24.3 |

| 4 or more people | 125 | 28.5 | 17.3 |

Socio-demographic characteristics were measured as of 2005; alcohol consumption and binging were measured in 2005 and 2007

Figure 1.

Estimated income trajectories followed by respondent households from 1968–20051

A large proportion of respondents were exposed to Hurricanes Katrina/Rita (Table 2); 69.2% of respondents were present during the hurricane, unsure about the safety or whereabouts of family or friends, or displaced from their home because of Katrina/Rita. However, a lower proportion experienced hurricane-related traumatic events or stressors: 17.4% experienced a traumatic event, 24.2% experienced property damage or loss, and 46.2% were exposed to at least one stressor in the six months after the hurricane.

Table 2.

Hurricane Katrina/Rita experiences reported by respondents

| Unweighted | Weighted | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | % or mean (SD) | % or mean (SD) |

| Hurricane Katrina/Rita event experiences | 349 | 79.5 | 69.2 |

| Present during hurricane force winds or major flooding | 287 | 65.4 | 52.5 |

| Unsure about the safety or whereabouts of family or friends | 187 | 42.6 | 36.2 |

| Displaced from home because of Katrina/Rita | 108 | 24.6 | 22.4 |

| Number of days displaced from home (Mean, SD) | -- | 31.2 (125.67) | 31.2 (421.9) |

| Hurricane-related traumatic events | 69 | 15.7 | 17.4 |

| Physically injured | 4 | 0.9 | 0.4 |

| Know someone who was injured or killed | 61 | 13.9 | 15.6 |

| Saw dead bodies | 13 | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| Number of hurricane-related traumatic events (Mean, SD) | -- | 0.2 (0.44) | 0.2 (1.4) |

| Property damage or loss | 123 | 28.0 | 24.2 |

| A lot of damage to property or possessions | 116 | 26.4 | 23.6 |

| Loss of sentimental possessions | 45 | 10.3 | 6.6 |

| Exposure to stressors in the first month after Katrina/Rita | 264 | 60.1 | 46.2 |

| Shortage of food | 127 | 28.9 | 17.2 |

| Shortage of water | 106 | 24.2 | 14.5 |

| Unsanitary conditions | 63 | 14.4 | 10.2 |

| Fear of crime | 79 | 18.0 | 11.2 |

| Feeling of isolation | 88 | 20.1 | 16.6 |

| Loss of electricity | 233 | 53.1 | 41.0 |

| Number of stressors in the first month after Katrina/Rita (Mean, SD) | -- | 1.6 (1.8) | 1.1 (5.2) |

| Exposure to traumatic events prior to Hurricanes Katrina/Rita | |||

| Low (0–1 traumatic events) | 224 | 51.0 | 46.7 |

| Medium (2–3 traumatic events) | 136 | 31.0 | 30.3 |

| High (4 or more traumatic events) | 79 | 18.0 | 23.0 |

| Social support received in the two months after Hurricanes Katrina/Rita | |||

| High | 119 | 27.2 | 25.7 |

| Medium | 107 | 24.4 | 22.8 |

| Low | 212 | 48.4 | 51.6 |

Table 3 shows the association between socio-demographic covariates, Hurricanes Katrina/Rita exposures and change in the number of drinks consumed in the past year, between 2005 and 2007. Having completed less than high school was associated with 92.7 more drinks per year than completing more than high school, while low exposure to lifetime traumatic events was marginally associated with 83.04 more drinks per year than high exposure to lifetime traumatic events (Model 1). Exposure to an additional hurricane-related traumatic event was associated with 79.2 more drinks per year (Model 1). Physical injury and seeing dead bodies were particularly predictive of change in the number of drinks consumed (Electronic Supplement Table 1). Each additional post-hurricane stressor was associated with 16.5 more drinks per year (Table 3, Model 3). Receiving low levels of social support after the hurricane was associated with 68.1 more drinks than receiving high levels of social support (Model 4). In the final model, age was marginally significantly associated with change in alcohol consumption: individuals aged 50 or more reported a drop in 76.86 more drinks than individuals aged 18–30.

Table 3.

Estimated association between pre-Katrina/Rita and Katrina/Rita-associated events and the difference in the total number of drinks consumed in the past year in 2005 and 20071

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | S.E.2 | Estimate | S.E. | Estimate | S.E. | Estimate | S.E. | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | (reference group) | |||||||

| Female | −19.32 | 35.38 | −25.27 | 35.64 | −25.37 | 35.36 | −13.3 | 35.4 |

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–30 | (reference group) | |||||||

| 31–40 | −29.25 | 42.43 | −28.78 | 42.84 | −21.84 | 42.64 | −29.36 | 42.5 |

| 41–50 | −11.16 | 43.07 | −14.74 | 43.44 | −11.73 | 43.16 | −17.38 | 43.23 |

| >50 | −69.74 | 45.39 | −62.05 | 45.65 | −53.55 | 45.55 | −76.86 | 46.11~ |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | (reference group) | |||||||

| Black | −39.32 | 43.33 | −29.7 | 43.68 | −35.02 | 43.3 | −35.08 | 43.3 |

| Other | 16.44 | 47.07 | 23.11 | 47.41 | 16.79 | 47.19 | 17.34 | 46.98 |

| Educational attainment | ||||||||

| <HS | 92.69 | 42.06* | 86.6 | 42.42* | 91.2 | 42.13* | 95.83 | 41.92* |

| HS | 33.64 | 31.45 | 29.89 | 31.71 | 29.24 | 31.48 | 32.45 | 31.31 |

| >HS | (reference group) | |||||||

| Lifetime income group | ||||||||

| Low income | −70.43 | 61.85 | −77.33 | 62.38 | −91.32 | 62.27 | −77.47 | 62.14 |

| Middle income | −1.92 | 37.7 | −2.52 | 38.01 | −9.74 | 37.94 | −4.63 | 37.75 |

| High income | (reference group) | |||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | (reference group) | |||||||

| Divorced, widowed or separated | 23.41 | 37.32 | 14.64 | 37.56 | 15.59 | 37.21 | 19.68 | 37.2 |

| Never married | 21.5 | 41.38 | 9.92 | 41.58 | 16.89 | 41.31 | 16.7 | 41.49 |

| Home ownership | ||||||||

| Own home | 58.91 | 34.25~ | 47.62 | 34.25 | 47.58 | 33.99 | 62.28 | 34.23~ |

| Family size | −7.41 | 10.36 | −5.39 | 10.41 | −7.44 | 10.4 | −10.76 | 10.47 |

| Traumatic events before Katrina/Rita | ||||||||

| Low | 83.04 | 39.61* | 61.18 | 38.89 | 64.93 | 38.66~ | 72.9 | 39.76~ |

| Medium | 51.23 | 42.3 | 34.46 | 42.11 | 38.51 | 41.84 | 53.74 | 42.18 |

| High | (reference group) | |||||||

| Number of hurricane-related traumatic events | 79.22 | 33.21* | 69.68 | 33.98* | ||||

| Property damage/loss | 1.66 | 31.65 | ||||||

| Number of stressors after Katrina/Rita | 16.51 | 7.98* | 14.66 | 8.16~ | ||||

| Post-Katrina/Rita social support | ||||||||

| Low | 68.05 | 34.44* | ||||||

| Medium | 41.22 | 37.28 | ||||||

| High | (reference group) | |||||||

Controlling for total number of drinks consumed in 2005

S.E. = Standard error

p<0.05;

p<0.10

After examining the average association between hurricane- and post-hurricane exposures and change in alcohol consumption, we also examined whether the relationship between hurricane-related exposures and alcohol use differed by two pre-hurricane indicators of vulnerability: lifetime trauma and income trajectory. The association between exposure to post-hurricane stressors and alcohol use differed marginally by lifetime income trajectory (Supplement Table 2, Model 6). As shown in Figure 2, only respondents with a low-income history exhibited a significant relationship between post-hurricane stressors and change in alcohol use: a greater number of stressors were marginally associated with a greater increase in the total number of drinks. We did not find a difference in the relation between hurricane-related traumatic events and alcohol use by prior income. However, the association between exposure to hurricane-related traumatic events and alcohol use differed by lifetime history of trauma (Supplement Table 2, Model 7). As shown in Figure 3, among those respondents with low and medium levels of exposure to lifetime trauma, experiencing hurricane-related traumas was associated with a further decrease in alcohol consumption; however, among those with high levels of lifetime trauma, experiencing hurricane-related traumas was associated with an increase in alcohol use over time. Further, by stratifying the analysis of the relationship between lifetime trauma and alcohol use by hurricane-related traumatic events, we found that the marginally significant negative association between lifetime trauma and alcohol use reported in Table 3 was restricted to individuals who had not experienced any hurricane-related traumas (Supplement Figure 1). We did not find a difference in the association between post-hurricane stressors and alcohol use by history of trauma.

Figure 2.

Estimated association between the number of post-hurricane stressors (x-axis) and the difference in the number of drinks consumed in 2007 vs. 2005, by 1968–2005 income history

Figure 3.

Estimated association between the number of hurricane-related traumatic events (x-axis) and the difference in the number of drinks consumed in 2007 vs. 2005, by lifetime exposure to traumatic events

Table 4 shows the association between socio-demographic covariates, Hurricanes Katrina/Rita exposures and the odds of binge drinking for more days in 2007, conditional on the number of days binged in 2005. Females had a lower odds of binge drinking on more occasions (OR: 0.29; 95% CI: 0.13, 0.68), while following a low-income trajectory was marginally associated with 5.33 times higher odds of reporting a higher frequency of binge drinking (95% CI: 0.94, 30.17) (Model 1). Exposure to more hurricane-related traumatic events was associated with 2.46 times higher odds of reporting a higher frequency of binge drinking (Model 1; 95% CI: 1.09, 5.55). Physical injury and seeing dead bodies were particularly predictive of binge drinking (Electronic Supplement, Table 1). Exposure to an additional post-hurricane stressor was marginally associated with 1.23 times higher odds of reporting more frequent binge drinking (Table 4, Model 3; 95% CI: 0.99, 1.51). The relationship between exposure to disaster-related stressors or traumatic events and binge drinking did not differ by income trajectory or lifetime traumatic experiences (Supplement Table 3).

Table 4.

Estimated association between pre-Katrina/Rita and Katrina/Rita-associated events and the odds of binge drinking for a higher number of days in 2007 (controlling for the number of days binged in 2005)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR1 | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | ||||||||||||

| Female | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.68 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.64 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.72 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 18–30 | (reference group) | |||||||||||

| 31–40 | 1.34 | 0.48 | 3.73 | 1.30 | 0.46 | 3.63 | 1.31 | 0.47 | 3.64 | 1.34 | 0.48 | 3.73 |

| 41–50 | 1.14 | 0.36 | 3.58 | 1.05 | 0.33 | 3.31 | 1.05 | 0.32 | 3.38 | 1.11 | 0.34 | 3.58 |

| >50 | 0.34 | 0.08 | 1.43 | 0.36 | 0.08 | 1.54 | 0.37 | 0.09 | 1.60 | 0.34 | 0.08 | 1.43 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| White | (reference group) | |||||||||||

| Black | 1.00 | 0.30 | 3.34 | 1.22 | 0.38 | 3.92 | 1.17 | 0.36 | 3.84 | 0.99 | 0.29 | 3.36 |

| Other | 1.51 | 0.48 | 4.80 | 1.57 | 0.50 | 4.93 | 1.60 | 0.50 | 5.12 | 1.52 | 0.47 | 4.91 |

| Educational attainment | ||||||||||||

| <HS | 1.37 | 0.43 | 4.35 | 1.18 | 0.38 | 3.66 | 1.24 | 0.39 | 3.90 | 1.43 | 0.44 | 4.66 |

| HS | 1.59 | 0.65 | 3.88 | 1.46 | 0.61 | 3.49 | 1.38 | 0.58 | 3.33 | 1.55 | 0.63 | 3.83 |

| >HS | (reference group) | |||||||||||

| Lifetime income group | ||||||||||||

| Low income | 5.33 | 0.94 | 30.17 | 4.23 | 0.76 | 23.46 | 4.02 | 0.73 | 22.16 | 4.71 | 0.82 | 26.88 |

| Middle income | 1.91 | 0.48 | 7.57 | 1.75 | 0.44 | 6.97 | 1.59 | 0.40 | 6.27 | 1.67 | 0.41 | 6.85 |

| High income | (reference group) | |||||||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Married | (reference group) | |||||||||||

| Divorced, widowed or separated | 2.04 | 0.67 | 6.22 | 1.76 | 0.59 | 5.28 | 1.82 | 0.61 | 5.45 | 1.99 | 0.65 | 6.13 |

| Never married | 1.50 | 0.61 | 3.71 | 1.23 | 0.51 | 2.95 | 1.34 | 0.55 | 3.26 | 1.58 | 0.63 | 3.94 |

| Home ownership | ||||||||||||

| Own home | 1.50 | 0.61 | 3.71 | 1.23 | 0.51 | 2.95 | 1.34 | 0.55 | 3.26 | 1.58 | 0.63 | 3.94 |

| Family size | 0.90 | 0.68 | 1.19 | 0.92 | 0.69 | 1.22 | 0.91 | 0.68 | 1.20 | 0.88 | 0.66 | 1.17 |

| Traumatic events before Katrina/Rita | ||||||||||||

| Low | 0.42 | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.95 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.85 | 0.37 | 0.13 | 1.04 |

| Medium | 0.79 | 0.28 | 2.23 | 0.69 | 0.25 | 1.91 | 0.68 | 0.25 | 1.87 | 0.80 | 0.28 | 2.27 |

| High | (reference group) | |||||||||||

| Number of hurricane-related traumatic events | 2.46 | 1.09 | 5.55 | 2.26 | 0.97 | 5.23 | ||||||

| Property damage/loss | 0.72 | 0.29 | 1.80 | |||||||||

| Number of stressors after Katrina/Rita | 1.23 | 0.99 | 1.51 | 1.20 | 0.96 | 1.49 | ||||||

| Post-Katrina/Rita social support | ||||||||||||

| Low | 1.21 | 0.45 | 3.27 | |||||||||

| Medium | 1.01 | 0.35 | 2.90 | |||||||||

| High | (reference group) | |||||||||||

OR=odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval

4. Discussion

This is one of the first studies, to our knowledge, that uses a prospective study design and a large population-based sample to assess the impact that degree of exposure to a large-scale natural disaster had on alcohol use. While other studies have found increases in alcohol use after natural disasters (Cepeda et al.; North et al., 2004; Reijneveld et al., 2005), we are only aware of one that used pre- and post-disaster measures of alcohol use (Rohrbach et al., 2009). We examined the association between exposure to disaster and post-disaster stressors and the range of alcohol consumption, from level of use to frequency of binge drinking.

Exposure to hurricane-related traumatic events was associated with more drinking and binge drinking after the hurricane. Prior research has found an association between exposure to traumatic circumstances surrounding a natural disaster, such as injuries, and later psychiatric function (Cairo et al., 2010; Galea et al., 2007; Mason et al., 2010). Further, several studies have shown that trauma exposure in settings other than disasters increases the risk for alcohol and drug use (Kilpatrick et al., 1997; Stewart, 1996; Wagner et al., 2009). It seems therefore plausible that experience of traumatic events surrounding a disaster such as Hurricanes Katrina/Rita would increase the risk of alcohol use and abuse.

Post-hurricane stressors also contributed to an increase in alcohol use and binge drinking. While a general measure of property damage/loss (loss of sentimental possessions or damage to property) was not associated with alcohol use, a more comprehensive measure of post-disaster stressors such as food and water shortage, loss of electricity or fear of crime, were associated with an increase in alcohol use and marginally associated with binge drinking frequency. This finding is consistent with theories suggesting that post-disaster resource loss, as well as the availability of post-disaster sources of social support, affects stress and the capacity to recover after mass trauma (Bleich et al., 2006; Hobfoll, 2001; Hobfoll et al., 2008; North et al., 2004). Selected studies have found that loss of resources such as income or employment contributed to alcohol use (Rohrbach et al., 2009) and post-traumatic stress disorder (Kun et al., 2009; Norris et al., 1999; Rhodes et al., 2010). Investment in housing reconstruction and infrastructure replacement, as well as social welfare programs that will act as buffers against temporary losses of income may thus play an important role in reducing the mental health burden after a disaster and can, in effect, be considered health interventions.

Social support in the two months following the disaster was associated with a decrease in alcohol use. Emotional and instrumental support might buffer average drinkers from managing their stress by self-medicating with alcohol (Glass et al., 2009). This finding is consistent with results reported by prior studies on post-disaster settings, which have found that social support is protective against emotional distress and substance abuse (Al-Turkait and Ohaeri, 2008; Baldomero et al., 2004; Bleich et al., 2006; Bonanno et al., 2007; Hardin et al., 1994; Hobfoll, 2001; Hobfoll et al., 2008).

In this study, we also present preliminary evidence about the particular vulnerability that individuals with a prior history of trauma may have to alcohol use after exposure to disaster-related traumatic events. Among individuals with low or medium levels of lifetime trauma, exposure to hurricane-related trauma had no significant association with change in alcohol use, while among those exposed to high levels of lifetime trauma, hurricane-related trauma was associated with an increase in alcohol use over time. Following the challenge model of resilience (Fergus and Zimmerman, 2005), this finding may indicate that individuals who are exposed to moderate levels of risk (in this case, low-to-mid-levels of lifetime trauma) learn to mobilize assets and resources in situations of adversity, such as a disaster-related trauma (Fergus and Zimmerman, 2005). In contrast, consistent with the notion of an “amplification effect”, exposure to extreme stress earlier in life (in this case, high levels of lifetime trauma) may “sensitize” individuals, promoting more adverse reactions to traumatic events in adulthood compared to individuals without such early life exposures (Kendler et al., 2004; Rudolph and Flynn, 2007). The particular vulnerability to increased alcohol use among individuals who were exposed to high lifetime and disaster-related trauma highlights the need to routinely assess substance abuse following traumatic exposure, and to shift away from a one-size-fits-all post-disaster mental health intervention, to an approach that particularly identifies those individuals at risk for having difficulty adjusting on their own (Litz, 2008; Litz et al., 2002).

Our findings also provide preliminary evidence that respondents of lower income may be particularly vulnerable to the stressors that ensue from a disaster (Bonanno et al., 2007; Rhodes et al., 2010). Part of this increased vulnerability could be because respondents of lower income lived in neighborhoods that were more flooded and recovered more slowly than more affluent neighborhoods (Finch et al., 2010). Higher vulnerability could also be due to the disproportionate accumulation of stress exposures over the lifecourse experienced by individuals in lower socioeconomic status (Lloyd and Turner, 2008; Turner and Lloyd, 1995; Turner and Lloyd, 2003). Failure to target safety planning and emergency stabilization, as well as reconstruction efforts to this particularly vulnerable population may serve to widen existing socioeconomic disparities in mental health.

This study has several limitations. First, the interactions between lifetime income or traumatic exposures and hurricane-related trauma and stressors are only preliminary results. Certain interactions were only marginally statistically significant and all interactions were limited by small sample sizes in the subgroups. Second, the measures of exposure to the hurricane and circumstances following this event were obtained two years after the event, which could have contributed to selective recall bias. However, the central presence of events such as losing one’s property or being displaced by the hurricane on people’s lives mitigates this concern. The measure of lifetime exposure to trauma was also retrospective and collected in the second interview. However, prior studies have found that retrospective measures of traumatic events are reliable and valid (Turner and Lloyd, 1995). Finally, the under-representation of males in the sample may have led to an under-estimation of the impact of the hurricanes on drinking outcomes.

This study constitutes one of the first prospective, population-based examinations of the role that exposure to a massive disaster has on substance use and misuse (Galea et al., 2003; Galea et al., 2004). Exposure to traumatic events and post-disaster stressors contributed to an increase in drinking, as well as to higher odds of binge drinking. Respondents with a history of lower income were at marginally higher risk of increased drinking after having experienced hurricane-related stressors, while respondents with a history of trauma were at higher risk of increased drinking after having experienced hurricane-related trauma. This study highlights the impact that post-disaster investment in reconstruction and recovery may have in decreasing the substance abuse burden from a disaster, and in preventing the post-disaster amplification of disparities in substance abuse.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Tables and figures showing additional results including analyses for interactive effects can be found as supplementary material by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org by entering doi:xxx/j.drugalcdep.xxx …

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al-Turkait FA, Ohaeri JU. Post-traumatic stress disorder among wives of Kuwaiti veterans of the first Gulf War. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aseltine RH, Gore S, Colten ME. The co-occurrence of depression and substance abuse in late adolescence. Dev Psychopathol. 1998;10:549–570. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldomero EB, Arrate MLC, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Baca-Garcia E. Mental disorders in victims of terrorism and their families. Medicina Clinica. 2004;122:681–685. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(04)74355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleich A, Gelkopf M, Melamed Y, Solomon Z. Mental health and resiliency following 44 months of terrorism: a survey of an Israeli national representative sample. BMC Medicine. 2006:4. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Galea S, Bucciarelli A, Vlahov D. What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:671–682. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Wallace D, Feinberg SL, Cagney KA. Neighborhood social processes, physical conditions, and disaster-related mortality: The case of the 1995 Chicago heat wave. Am Sociol Rev. 2006;71:661–678. [Google Scholar]

- Cairo JB, Dutta S, Nawaz H, Hashmi S, Kasl S, Bellido E. The Prevalence of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Adult Earthquake Survivors in Peru. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2010;4:39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Assessment of health-related needs after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita--Orleans and Jefferson Parishes, New Orleans area, Louisiana, October 17–22, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006a;55:38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Health hazard evaluation of police officers and firefighters after Hurricane Katrina--New Orleans, Louisiana, October 17–28 and November 30–December 5, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006b;55:456–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Surveillance in hurricane evacuation centers--Louisiana, September-October 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006c;55:32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda A, Valdez A, Kaplan C, Hill LE. Patterns of substance use among hurricane Katrina evacuees in Houston, Texas. Disasters. 34:426–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2009.01136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda A, Valdez A, Kaplan C, LEH Patterns of substance use among Hurricane Katrina evacuees in Houston, Texas. Disasters. 2010;34:426–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2009.01136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Hanks JS, Eggelston KS, Riser J, Tie PG, Chronister KJ. Social and mental health needs assessment of Katrina evacuees. Disaster Manag Response. 2006;4:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.dmr.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch C, Emrich CT, Cutter SL. Disaster disparities and differential recovery in New Orleans. Population and Environment. 2010;31:179–202. [Google Scholar]

- Fothergill A, Peek L. Poverty and disasters in the United States: a review of recent sociological findings. Natural Hazards. 2004;32:89–110. [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, Vlahov D. Contextual determinants of drug use risk behavior: a theoretic framework. J Urban Health. 2003;80ii(4 Suppl 3):50–8. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Brewin CR, Gruber M, Jones RT, King DW, King LA, McNally RJ, Ursano RJ, Petukhova M, Kessler RC. Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1427–1434. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Hadley C. Public Health Preparedness for Disasters: An ecological perspective. In: Sheinfeld S, Arnold G, editors. Health promotion and practice. Josey Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2006. pp. 427–444. [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The social epidemiology of substance use. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:36–52. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Tracy M, Norris F, Coffey S. Financial and social circumstances and the incidence and course of PTSD in Mississippi during the first two years after Hurricane Katrina. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21:357–368. doi: 10.1002/jts.20355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass K, Flory K, Hankin BL, Kloos B, Turecki G. Are Coping Strategies, Social Support, and Hope Associated with Psychological Distress among Hurricane Katrina Survivors? J Soc Clin Psychol. 2009;28:779–795. [Google Scholar]

- Green B, Grace M, Gleser G. Identifying survivors at risk: Long-term impairment following the Beverly Hills Super Club fire. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:672–678. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.5.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin SB, Weinrich M, Weinrich S, Hardin TL, Garrison C. Psychological Distress of Adolescents Exposed to Hurricane Hugo. J Trauma Stress. 1994;7:427–440. doi: 10.1007/BF02102787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, Aharonovich EA, Alderson D. Alcohol consumption and posdraumatic stress after exposure to terrorism: Effects of proximity, loss, and psychiatric history. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:2268–2275. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill M. The Panel Study of Income Dynamics--A User’s Guide. Sage Publications; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing Conservation of Resources theory. Appl Psychol-Int Rev-Psychol Appl-Rev Int. 2001;50:337–370. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Canetti-Nisim D, Johnson RJ, Palmieri PA, Varley JD, Galea S. The association of exposure, risk, and resiliency factors with PTSD among Jews and Arabs exposed to repeated acts of terrorism in Israel. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21:9–21. doi: 10.1002/jts.20307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S, Williams R, Yule W. Crisis support, attributional style, coping style, and post-traumatic symptoms. Pers Individ Dif. 1992;13:1249–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Kar N, Mohapatra PK, Nayak KC, Pattanaik P, Swain SP, Kar HC. Post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents one year after a super-cyclone in Orissa, India: exploring cross-cultural validity and vulnerability factors. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Kuhn JW, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse, stressful life events and risk for major depression in women. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1475–1482. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400265x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Galea S, Jones RT, Parker HA. Mental illness and suicidality after Hurricane Katrina. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:930–939. doi: 10.2471/blt.06.033019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Üstün T. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationships between violent assault and substance use in women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:834–847. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kun P, Han S, Chen X, Yao L. Prevalence and risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder: a cross-sectional study among survivors of the Wenchuan 2008 earthquake in China. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:1134–1140. doi: 10.1002/da.20612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT. Early Intervention for Trauma: Where Are We and Where Do We Need to Go? A Commentary. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21:503–506. doi: 10.1002/jts.20373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Gray MJ, Bryant RA, Adler AB. Early intervention for trauma: Current status and future directions. Clin Psychol-Sci Pract. 2002;9:112–134. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd DA, Turner RJ. Cumulative lifetime adversities and alcohol dependence in adolescence and young adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93:217–226. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason V, Andrews H, Upton D. The psychological impact of exposure to floods. Psychol Health Med. 2010;15:61–73. doi: 10.1080/13548500903483478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS. Group-Based Modeling of Development. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Vargas-Carmona J, Galaif ER. Drug problems and Psychological Distress among a community sample of adults: Predictors, consequences, or confound? J Community Psychol. 1999;27:405–429. [Google Scholar]

- Norris F, Perilla J, Riad J, Kaniasty K, Lavizzo E. Stability and change in stress, resources, and psychological distress following natural disaster: Findings from Hurricane Andrew. Anxiety, Stress and Coping. 1999;12:363–396. doi: 10.1080/10615809908249317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Kawasaki A, Spitznagel EL, Hong BA. The course of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse, and somatization after a natural disaster. J Ner Men Dis. 2004;192:823–829. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000146911.52616.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek MK, Cutchin MP, Freeman DH, Perez NA, Goodwin JS. Perceived health change in the aftermath of a petrochemical accident: an examination of pre-accident, within-accident, and post-accident variables. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:106–112. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.049858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reijneveld SA, Crone MR, Schuller AA, Verhulst FC, Verloove-Vanhorick SP. The changing impact of a severe disaster on the mental health and substance misuse of adolescents: follow-up of a controlled study. Psychol Med. 2005;35:367–376. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes J, Chan C, Paxson C, Rouse CE, Waters M, Fussell E. The Impact of Hurricane Katrina on the Mental and Physical Health of Low-Income Parents in New Orleans. Am J Orthopsychiatr. 2010;80:237–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman JA, Rospenda KM, Cloninger L. Terrorism, Distress, and Drinking Vulnerability and Protective Factors. J Ner Men Dis. 2009;197:909–917. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181c29a39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez S, et al. Rapid needs assessment of Hurricane Katrina evacuees-Oklahoma, September 2005. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2006;21:390–395. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x0000409x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbach LA, Grana R, Vernberg E, Sussman S, Sun P. Impact of Hurricane Rita on Adolescent Substance Use. Psychiatry-Interpers Biol Process. 2009;72:222–237. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2009.72.3.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum S. US health policy in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. JAMA. 2006;4:437–440. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M. Childhood adversity and youth depression: Influence of gender and pubertal status. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19:497–521. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder J, Polusny M. Risk factors for adolescent alcohol use following a natural disaster. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2004;19:122–127. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00001576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seplaki CL, Goldman N, Weinstein M, Lin YH. Before and after the 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake: Traumatic events and depressive symptoms in an older population. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:3121–3132. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH. Alcohol abuse in individuals exposed to trauma: A critical review. Psychol Bull. 1996;120:83–112. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. Lifetime traumas and mental health: The significance of cumulative adversity. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:360–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. Cumulative adversity and drug dependence in young adults: racial/ethnic contrasts. Addiction Mar. 2003;98(3):305–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KD, Brief DJ, Vielhauer MJ, Sussman S, Keane TM, Malow R. The Potential for PTSD, Substance Use, and HIV Risk Behavior among Adolescents Exposed to Hurricane Katrina. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44:1749–1767. doi: 10.3109/10826080902963472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner M, Weichold K, Silbereisen RK. Trajectories of Alcohol Use Among Adolescent Boys and Girls: Identification, Validation, and Sociodemographic Characteristics. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:62–75. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.