Abstract

Background

Vulnerabilities in the medication management process can lead to serious patient harm. In intensive care units (ICUs), nurses represent the last line of defense against medication errors. Proactive risk assessment (PRA) offers methods for determining how processes can break down and how people involved in such processes can contribute to or recover from a breakdown. Such methods can also be used to identify ICU nurses’ contribution to the quality and safety of medication management.

Methods

A PRA method was conducted in a cardiovascular ICU to identify and evaluate failure modes in the nursing medication management process. The contributing factors to the failure modes and the recovery processes used by nurses were also characterized.

Results

A total of 54 failure modes were identified across the seven steps of the medication management process. For the 4 most critical failure modes, nurses listed 21 contributing factors and 21 recovery processes. Ways were identified to redesign the medication management process, one of which consists of dealing with work system factors that contribute to the most critical failure modes.

Conclusions

From a data-analysis viewpoint, the PRA method permits one to address a variety of objectives. Different scoring methods can be used to focus on either frequency or criticality of failure modes; one may also focus on a specific step of the process under study. Developing efforts towards eliminating or mitigating contributing factors would help reduce the criticality of the failure modes in terms of their likelihood and impact on patients and/or nurses. Developing systems to support the recovery processes used by nurses may be another approach to process redesign.

“…on average, a hospital patient is subject to at least one medication error per day…”1

Such a high rate of hospital medication errors2 is alarming; it is estimated that at least 380,000 preventable adverse drug events (ADEs) occur annually from medication errors3 at an estimated annual cost of $3.5 billion in 2006.1 In intensive care units (ICUs), preventable ADEs and potential ADEs occur at nearly twice the rate as non-ICU settings.4 The higher rates of ADEs in ICUs is related to patient characteristics (ICU patients are the most critically ill patients), the complex environment of ICUs, and the volume of medications prescribed per patient.5,6 ICU patients are less likely to recover from ADEs because of their vulnerable health status.7

A number of medication safety strategies have been developed to address vulnerabilities and failures during the stages of the medication use process—prescribing, transcribing, dispensing, administering, and monitoring.1 Ultimately, nurses represent the last line of defense against medication errors in ICUs.8 It is therefore important to study the nature of nursing work in ICUs so work systems and processes of care can be designed to support nurses’ work.9 This study uses a proactive risk assessment (PRA) methodology to assess the nursing medication management process in an ICU. We describe the results of the PRA analysis and the different methods that can be used to identify and evaluate failure modes in the medication management process. Using nurses’ input, we also identify contributing factors to the failure modes and the recovery processes that ICU nurses use in dealing with various failure modes in the medication management process.

PRA is a collection of methods for determining how processes can break down and how people involved in such processes can contribute to or recover from breakdown.10 PRA methods can help to identify performance obstacles and facilitators in ICU work systems and to design approaches for improving the design of ICU work systems and processes.9

PRA methods have been used to assess diverse processes and outcomes. For example, Apkon et al.11 conducted an FMEA of the process of continuous drug infusion delivery in a pediatric ICU in an attempt to redesign the IV delivery process and improve patient safety and efficiency in staff work flow. Esmail et al.12 conducted a Healthcare Failure Mode and Effect Analysis (HFMEA) in four adult ICUs to assess the process of ordering and administering potassium chloride and potassium phosphate. Strengths and weaknesses of PRAs have been described.13,14 Strengths include the multidisciplinary aspect of PRA teams,12,15–17 patient involvement,15 and improved understanding of the process.18 Weaknesses include the time necessary to complete a PRA18–20; Wetterneck et al.,16 for example, reported that the FMEA of an adult inpatient medication system required more than 46 hours of meetings for nearly five months. PRAs have also been criticized because of the tedious process involved in and difficulty of the analysis,18,20 problems with the scoring system,16,17,19 and unreliability of scoring.21 Other challenges to successful PRAs include not conducting the requisite preliminary process mapping, the team’s lack of experience with PRA, limited involvement of stakeholders in the PRA team, a flawed understanding of the processes and systems under study, inconsistent attendance of participants, insufficient time for discussion during PRA team meetings, a lack of focus, and lack of experienced facilitators.16,22 In this study, we describe a PRA method that addresses many of these weaknesses, in particular the amount of time for completing the PRA, insufficient understanding of the process, and involvement of stakeholders.

Methods

The PRA described in this article was part of a larger project whose purpose was to identify nurses' contributions to the quality of medication management.23 *For more details, see the project Web site: http://cqpi.engr.wisc.edu/rwj_home

The PRA relied on various data collection methods used in the larger project. Initial data collection consisted of observing nurses in their work environment for 2 to 4 hours. A total of 39 separate periods of observations were conducted for a total of 128 hours; they also conducted two sets of individual semistructured interviews with nurses (each interview lasted about one hour). The purpose of the first set of interviews was to investigate decision-making processes used by nurses in different patient care situations. The second set of interviews investigated nurses’ perceptions of medication management. For each set of interviews, 12 nurses were interviewed.

Setting

The study was conducted in a 15-bed cardiovascular intensive care unit (CVICU) of a tertiary referral hospital. Patients are generally admitted to the CVICU directly from the cardiac operating room. Although a patient’s typical stay in the CVICU lasts about 24 hours, patient stays may last up to one month, depending on the patient’s condition. Patients are usually transferred to the cardiovascular intermediate care unit. The nursing staff is composed of 54 nurses. Most of them work 12-hour shifts and care for 1 to 2 patients per shift. The hospital pharmacy is open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The CVICU shared pharmacy services with another unit.

In the CVICU, the health care team does not perform bedside rounds but rather conducts collective sit-down rounds. The charge nurse represents nurses at the rounds. Throughout the day, physicians consult their own patients. Families are allowed to visit patients at any time, day or night.

Recruitment and Scheduling

We presented the PRA method to the CVICU nursing council and asked for their endorsement and participation. We recruited nurses of the council to participate in the PRA; seven volunteered to participate in the PRA team. The PRA team also included four researchers—four industrial engineers specialized in human factors. We then scheduled two focus groups that took place about two months apart from each other, allowing us sufficient time between meetings to analyze data gathered in the first focus group, that were then used in the second focus group.

Defining the Medication Management Process and Identifying Failure Modes

We used observation and interview data of ICU nurses’ work to develop a rich description of the nursing medication management process. We defined the medication management process as composed of the following seven steps:

Assessing the patient

Obtaining a medication

Administering a medication

Monitoring/reevaluating a patient

Educating the patient and/or the family during the ICU stay

Educating the patient and/or the family in preparation for discharge

Conducting the nurse-to-nurse handoff

Each process step was described in detail by a list of tasks identified in the observations and interviews. The observation and interview data also allowed us to identify a preliminary list of failure modes that can occur at each step of the medication management process. The term failure mode had been chosen after a discussion with the nurse manager, who agreed that it was sufficiently clear to participants in the PRA to convey the idea that "anything can go wrong in the process."

The researchers created a document that described the steps of the medication management process and the failure modes associated with each step; this document was reviewed by a former CVICU nurse for correctness of terminology and clarity. In preparation for the first focus group, we asked nurses on the PRA team to provide wrtten feedback on the document. One week before the first focus group, we collected the (minimal) feedback (from four nurses) and integrated it in a revised document.

First Focus Group: Rating Failure Modes and Identifying Recovery Processes

The objective of the first focus group was for nurses to rate failure modes in the medication management process and to describe the methods they use to recover from those failures. The focus group took place in a meeting room located in the hospital. The room was organized to facilitate discussion and participation from all nurses. A spreadsheet listing the steps of the medication management process and the previously identified failure modes associated with each step was projected in the front of the room. An audiorecorder was placed in the center of the room. A poster displaying the main steps of the nursing medication management process was displayed on a Flip chart next to the projection screen.

The researchers were assigned specific roles and tasks. One researcher [P.C.] provided an introduction about the PRA process and facilitated the discussion. Another researcher [A.S.H.] served as a content and process backup for the facilitator and timekeeper. Two other researchers who had conducted observations and interviews [H.F., A.J.R.) helped in answering nurses' questions on content; they were also in charge of updating the document projected on the screen, therefore providing immediate feedback to the PRA team. They also took notes of the discussion.

After presenting the overall objective of the PRA, the facilitator described the Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol and handed out information sheets to nurses. We then asked the nurses to provide verbal consent for audiotaping the discussion; they all agreed. The facilitator then described the expected role of nurses in the PRA, that is, to review and revise the list of failure modes and identify recovery processes.

Nurses were asked to consider the first step of the medication management process and to review the corresponding list of failure modes. As the nurses provided feedback on the failure modes, some failure modes were removed and others added. Then for each failure mode, nurses were asked to rate the failure modes using three criteria and raising cards corresponding to their response:

The likelihood of occurrence of the failure mode (How frequently does this failure mode occur?): unlikely to occur ("+" card), very likely to occur ("−" card), or between low and high ("+/−" card)

The impact of the failure mode on the patient (How critical is the impact of this failure mode on patients in terms of harm and lack of well-being?): unlikely to cause harm to the patient or affect the patient well-being (green card), very likely to cause harm to the patient or affect the patient well-being (red card), or between low and high (orange card)

The impact of the failure mode on nurses (How critical is the impact of this failure mode on you and your ability to perform your job or complete that step of the medication management process?): unlikely to negatively affect nurses' ability to perform their job (green card), very likely to negatively affect nurses' ability to perform their job (red card), or between low and high (orange card).

To record results of the rating, nurses were asked to select a card corresponding to their rating and to display it. If there was wide variety of ratings by the nurses, the facilitator would ask them to discuss the failure mode and then rate the failure mode again. Results of the rating were updated and displayed on the screen to provide immediate feedback to the PRA participants. After each rating, nurses were asked to list recovery processes they use to deal with each failure mode (How do you recover from this failure mode?).

On completion of the first focus group, the researchers listened to the audiotape of the first PRA meeting to provide an opportunity to correct and revise what had been recorded during the meeting. We then asked nurses for their feedback on a revised version of the document. (Additional information about the first focus group can be found elsewhere.23)

Second Focus Group: Identifying Contributing Factors

The second focus group was run in a manner similar to the first focus group, in terms of both layout and roles of the team members. Only five of the seven nurses who had participated in the first focus group could attend. At the beginning of the second focus group, the facilitator went through the same steps as in the first focus group regarding the PRA process, its objectives, and the IRB.

For each failure mode previously identified, nurses were asked to list all “contributing factors”—the factors that can contribute to the occurrence of the failure mode. Examples were given in light of the elements of the work system model9,24 —that is, technology and tools (for example, the tether scanner is too short), the organization (nurses are not provided with proper training on patient education), the person (the physician forgot to discontinue a medication), the tasks (there are interruptions during nurse-to-nurse handoff) and the environment (the hallway is too loud). In reviewing the failure modes, nurses indicated that some of them were not described in sufficient detail and proposed to refine some of them. The researchers recorded the contributing factors, which that were immediately projected on the screen so all PRA team participants could see the results.

On completion of the second focus group, the researchers listened to the audiotape of the meeting and revised and corrected the list of contributing factors—and then asked PRA participants to provide feedback on the revised document.

Evaluating the PRA

At the end of the second PRA focus group, we asked the nurses to anonymously fill out a one-page survey to evaluate the PRA process (Appendix 1, available in online article). The surveys were collected prior to the nurses leaving the meeting room.

Results

Identifying and Evaluating Failure Modes

A total of 54 failure modes were identified across the seven steps of the medication management process: 14 failure modes associated with "assessing the patient, " 11 with "obtaining a medication,” 17 with "administering a medication, " 2 with "monitoring/reevaluating the patient, " 2 with "educating the patient and/or the family during the ICU stay", 2 with "educating the patient and/or the family in preparation for discharge, " and 6 with "nurse-to-nurse handoff.”

Scoring

We assigned the following values to the ratings:

1 for low likelihood and low impact on the patient or the nurse

2 for moderate likelihood and moderate impact on the patient or the nurse

3 for high likelihood and high impact on the patient or the nurse.

We then examined scores for each dimension–likelihood and impact on patients and impact on nurses—and compared the failure modes. One way of using the scores would be to evaluate a combined effect of likelihood and impact on patients and nurses. Multiplying the likelihood score and the impact on patient score produces a scale ranging from 1×1 = 1 to 3 × 3=9, which can help identify the most frequent failure modes that have the most critical impact on the patient. A similar method can be used by multiplying the likelihood score and the “impact on nurses” score. Multiplying the three scores produces a score ranging from 1×1×1 = 1 to 3×3×3 = 27, which can help identify the most frequent failure modes that have the most critical impact on patients and nurses.

Organizations might categorize the failure modes differently according to their specific objective. In PRAs based on the FMEA method, failure modes that have a high probability, high severity, and low detectability11 are the main focus for follow up. However, one may also want to consider the most frequent failures modes, regardless of their criticality. Even if frequent failures have minor effects, they can rapidly increase nursing workload and become a source of stress.

Table 1 shows the 10 failure modes that are the most critical in terms of likelihood and impact on patients and impact on nurses. Depending on the scoring system used by an organization, the high-priority failure modes may be different. For instance, the 10 most critical failure modes in terms of likelihood and impact on patients and impact on nurses are not the most frequent failure modes; none of these failure modes are ranked in the top for likelihood. Also, the failure mode D2 "Inadequate monitoring/reevaluating" would be a priority according to the combined (likelihood × impact on patients × impact on nurses) scoring method but would not be a high priority if the individual scores were considered.

Table 1.

Different Ways to Sort Failure Modes According to the Score To Be Considered*

| Likelihood × Impact on patient × Impact on nurse |

Likelihood × Impact on patient |

Likelihood × Impact on nurse |

Likelihood | Impact on patient |

Impact on nurse |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C9 | IV pump malfunctioning | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| C17 | No line available to administer IV med | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| C15 | Patient status contra-indicates med | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | - |

| A3 | Critical equipment not working | 4 | 7 | 8 | - | 1 | 1 |

| C10 | RN lacks knowledge on med | 5 | 6 | 7 | - | 2 | - |

| C5 | MAR is inaccurate: discontinued med still appears on MAR | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | - | - |

| G2 | Receiving incomplete information: recognize later in the shift | 7 | 4 | 2 | 2 | - | - |

| D2 | Inadequate monitoring/reevaluating | 8 | 5 | 6 | - | - | - |

| A11 | RN does not perform patient assessment updates | 9 | - | 5 | - | - | 1 |

| C14 | Patient allergic to med | 10 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

The failure modes are sorted in decreasing criticality score and ranked from 1 to 10. The ranks are produced by multiplying two scores and by individual scores. Identical rankings (identical numbers in the same column) correspond to equal scores for different failure modes. IV, intravenous; med, medication; RN, registered nurse; MAR, medication administration record.

Identifying Key Failure Modes

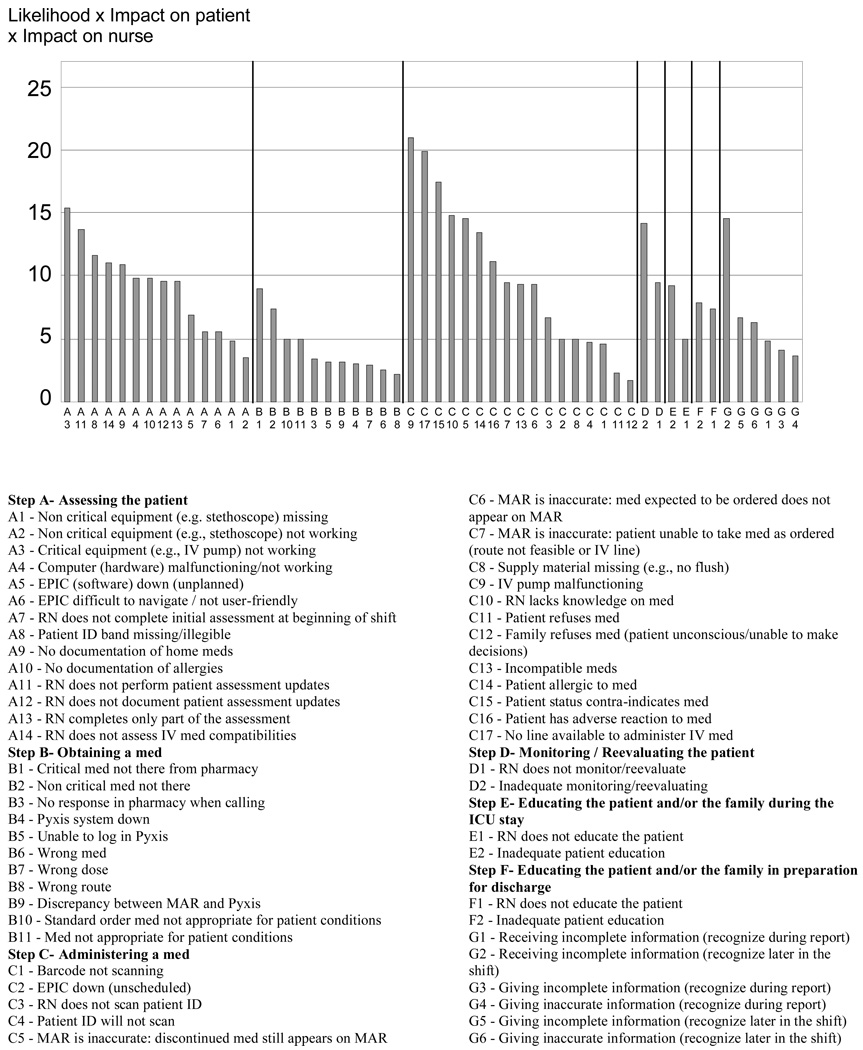

Another approach to identify the failure modes for follow-up and intervention is to focus on a particular step of the medication management process instead of identifying the most critical failure modes across the entire process. If the organization wants to focus on the most critical failure modes for a specific step, it should examine the criticality of the failure modes for that particular step. Figure 1 shows how the most critical failure modes can be sorted by step of the medication management process or for the entire process.

Figure 1. Failure Modes Sorted by Step of the Medication Management Process and by Criticality.

The figure shows how the most critical failure modes can be sorted by step of the medication management process or for the entire process. Criticality (likelihood × impact on patient × impact on registered nurse) ranges from 1.75 for failure mode C12 (family refuses to medication [patient unconscious/unable to make decisions] to 21 for failure mode C9 (IV pump malfunctioning). IV, intravenous; RN, registered nurse; ID, identification; MAR, medication administration record; ICU, intensive care unit.

Approach to Redesigning the Medication Management Process

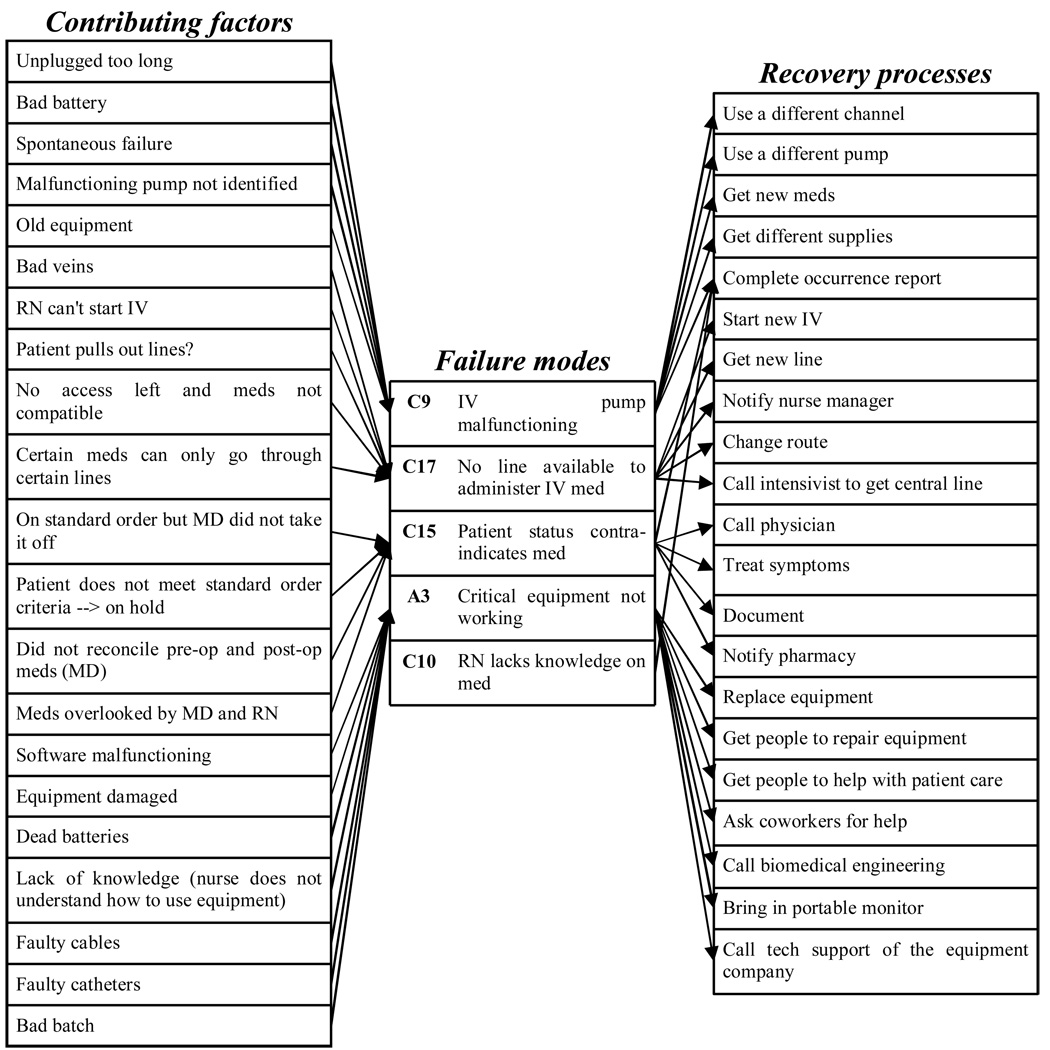

There are different ways to analyze the PRA data to redesign and improve the medication management process. For sake of discussion, we arbitrarily decided to focus on the four most critical failure modes in terms of the combination of likelihood, impact on the patient, and impact on the nurse (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cross-section for the Four Most Critical (likelihood × impact on patient × impact on RN > 15) Failure Modes of the Medication Management Process.

A cross-section is shown for the most critical (score of > 15 for likelihood × impact on patient × impact on registered nurse). IV, intravenous; MD, physician; RN, registered nurse.

Identifying Contributing Factors

After the most critical failure modes have been identified, one can focus on the specific work system factors that contribute to those failure modes (Figure 2). One way of redesigning a work process consists of addressing factors that contribute to the most critical failure modes. Therefore, developing efforts towards eliminating or mitigating contributing factors would help reduce the criticality of the failure modes in terms of likelihood and impact on patient and/or nurse.

For the four most critical failure modes, nurses listed 21 contributing factors. Some of these factors are related to the equipment (for example, damaged equipment, faulty catheters) or the technologies (software malfunctioning) used on the unit, the organization (the physician was supposed to discontinue a medication from the medication administration record but it still appears), or the patient (the patient pulled out the IV lines). These findings could be shared with upper management to develop organizational priorities for work-system redesign.

Identifying Recovery Processes

Focusing on the most critical failure modes can also produce a list of important recovery processes used by nurses (see Figure 2). Some of the recovery processes consist of notifying other providers from the care team (for example, call the physician, notify the pharmacist), replacing the equipment (use a different pump, bring in a portable monitor), or documenting (complete an occurrence report). Supporting these recovery processes may be another approach to work-process redesign.

Evaluating the PRA Method

Nurses' Responses to the Evaluation of the PRA

A total of five nurses responded to the one-page questionnaire on the PRA evaluation, as follows:

To the question "How useful was the PRA? ", on a scale ranging from 1 (no, not at all useful) to 5 (yes, definitely useful), the average of nurses' responses was 4.2 (range, 4 to 5).

To the question "How willing are you to participate in a PRA again? ", on a scale ranging from 1 (no, not at all willing) to 5 (yes, definitely willing), the average of nurses' responses was 4.0 (range, from 3 to 5).

To the question "How much did the PRA contribute to your knowledge/understanding of nurses' contribution to the quality of medication management? ", on a scale ranging from 1 (almost nothing) to 5 (a lot), the average of nurses' responses was 4.2 (range, 3 to 5).

Overall, the nurses provided a positive evaluation of the PRA. However, in the open-comments section, two nurses shared their concern about the length of the focus groups and suggested shorter time frames or breaks.

Advantages of the PRA Method

Discussion

Main advantage of the PRA method to evaluate the nursing medication management process, as described in this article, is its adaptability. For example, we evaluated the impact of failure modes on both patients and nurses; most often, PRA methods focus on patient outcomes and do not consider the effects of process vulnerabilities and failures on the people involved in the process. From a data-analysis viewpoint, the PRA method permits one to address a variety of objectives. Different scoring methods can be used to focus on either frequency or criticality of failure modes; one may also focus on a specific section of the process under study. Our PRA method systematically addressed the work-system factors contributing to the failure modes in the process, as well as recovery processes used by nurses to deal with the failure modes. Any effort aimed at improving the process and either eliminating or mitigating failure modes needs to consider characteristics of the work system (that is, contributing factors), as well as the recovery processes used by nurses. It is important to improve the design of the work system (i.e. contributing factors) as well as support and improve the ability of nurses to recover from failure modes that could lead to critical events.

The other benefit of this PRA method is its efficiency. Indeed, most PRA methods rely on the teams to provide data on the process under study. In our study, we collected most of the data on the process and its failure modes before the PRA team met for the first time. Substantial data collection and analysis were completed in preparing for the focus groups; in addition, we sought nurses' feedback on the preliminary analysis. This made the participation of the process stakeholders more efficient and less taxing, which probably contributed to the high level of satisfaction that the nurses expressed regarding the PRA method.

Although having the research team provide the process data contributed to the efficiency of this PRA, an additional benefit was identified by the organization. As noted earlier, a major challenge to conducting a successful PRA is a flawed understanding of the processes and systems being assessed. Two sources of flawed understanding when “insiders” are gathering process data are (1) being so close to the process that some process steps are taken for granted and not fully articulated and analyzed during a PRA and (2) not accounting for Work-arounds that are part of daily practice but not defined—and therefore unavailable for full articulation and analysis.

Another strength of the PRA method as described in this paper is the collegiality of the nurses who participated on the PRA team. These nurses, who all belonged to the CVICU nursing council, were used to working together on a regular basis. There seemed to be mutual trust among them: they were comfortable in sharing their experience and the challenges they face on a daily basis when managing medications. As CVICU nursing council members, they were likely to have developed an in-depth understanding of their own challenges as well as that of others. They probably developed an ability to reflect on their own practice, and this contributed to the quality of the information collected on failure modes, contributing factors and recovery processes in the medication management process.

A final strength also identified by the organization, is the flexibility of the scoring system to prioritize improvement initiatives for assignment to a variety of teams and councils. For example, failure modes that scored high on criticality for patient safety can be assigned to the medication process improvement team and incorporated into the participating hospital’s Patient Safety Plan. Failure modes that scored high on nurse criticality can be assigned to the practice council for work-flow redesign or to the management council to guarantee that necessary resources are available at the bedside.

Because we recruited the nurses from a single committee, there is the potential for bias in their perceptions of failure modes in the medication management process. They may have developed a common but biased conceptualization of the process and its failures.

In preparing for the focus groups, as stated, we asked for written feedback from nurses regarding preliminary results and analysis of the medication management process. Although it would have been preferable to obtain verbal feedback, our choice of written feedback reflected a need to maximize flexibility and lessen the amount of time nurses would be asked to commit to the project. It is possible this affected the quality of the feedback provided by nurses who did not have an opportunity to elaborate.

Finally, the extensive data collection and data analysis performed in preparing for the focus groups involved significant time (about 100 hours of data collection and analysis in preparation for the PRA, and 40 hours of analysis of the data obtained during the focus groups) on the part of the researchers. The PRA team meetings were run efficiently, but overall the PRA method required significant resources.

Conclusion

The adapted PRA method we used in this study was intended to identify failure modes in the nursing medication management process, their contributing factors, and the recovery processes used by nurses. Because of its adaptability, this method is a powerful means of addressing a variety of objectives, whether they concern the process (for example, most critical failure modes, specific steps in the process) or the strategic approach (reducing the contributing factors, supporting recovery processes). Therefore, we advise that the organization orient the process redesign according to its specific goals.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant 61148 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The authors thank the nurses and the leadership of the intensive care unit, as well as the management of the hospital in which the study was conducted.

Support was provided by the Community-Academic Partnerships core of the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (UW ICTR), grant 1 UL1RR025011 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award program of the National Center for Research Resources.

Contributor Information

Hélène Faye, formerly Postdoctoral Research Associate, Center for Quality and Productivity Improvement, Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, is Human Factors Engineer, Institut de Radioprotection et de Sûreté Nucléaire, Direction Sûreté des Réacteurs-Service d'Etude des Facteurs Humains, Fontenay-aux-Roses, France

A. Joy Rivera-Rodriguez, Doctoral Candidate, Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Ben-Tzion Karsh, Associate Professor, Center for Quality and Productivity Improvement

Ann Schoofs Hundt, Research Scientist, Center for Quality and Productivity Improvement

Christine Baker, Administrative Director, Quality and Safety Systems, St. Mary’s Hospital, Madison

Pascale Carayon, Director, Center for Quality and Productivity Improvement

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Preventing medication errors. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates DW, Boyle DL, Vliet MVV, et al. Relationship between Medication Errors and Adverse Drug Events. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1995 Apr;10(4):199–205. doi: 10.1007/BF02600255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Classen DC, Pestotnik SL, Evans RS, et al. Adverse drug events in hospitalized patients: Excess length of stay, extra costs and attributable mortality. JAMA. 1997;277(4):301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cullen DJ, Jean Sweitzer B, Bates DW, et al. Preventable adverse drug events in hospitalized patients: a comparative study of intensive care and general care units. Crit Care Med. 1997 Aug.25(8):1289–1297. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199708000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moyen E, Camire E, Stelfox HT. Clinical review: Medication errors in critical care. Critical Care. 2008;12(2) doi: 10.1186/cc6813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valentin A, Bion J. How safe is my intensive care unit? An overview of error causation and prevention. Current Opinion in Critical Care. 2007;13:697–702. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f12cc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers AE, Dean GE, Hwang W-T, et al. Role of registered nurses in error prevention, discovery and correction. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008 Apr.17:117–121. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.022699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kopp BJ, Erstad BL, Allen ME, et al. Medication errors and adverse drug events in an intensive care unit: Direct observation approach for detection. Critical Care Medicine. 2006;34:415–425. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000198106.54306.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carayon P, Schoofs Hundt A, Karsh B-T, et al. Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Dec.15 Suppl. 1:i50–i58. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carayon P, Faye H, Schoofs Hundt A, et al. Patient safety and proactive risk assessment. In: Lih Y, editor. Handbook of Healthcare Delivery Systems. To be published. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Apkon M, Leonard J, Probst L, et al. Design of a safer approach to intravenous drug infusions: failure mode effects analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004 Aug. 113(4):265–271. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.007443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esmail R, Cummings C, Dersch D, et al. Using healthcare failure mode and effect analysis tool to review the process of ordering and administrating potassium chloride and potassium phosphate. Healthc Q. 2005 Oct.8(Special Issue):73–80. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2005.17668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Habraken MMP, Van der Schaaf TW. Requirements for prospective risk analysis in health care. Healthcare systems, Ergonomics and Patient Safety (HEPS) International Conference; July 25–27, 2008; Strasbourg, France. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Israelski EW, Muto WH. Human factors risk management in medical products. In: Carayon P, editor. Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care and Patient Safety. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 2007. pp. 615–647. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Tilburg CM, Leistikow IP, Rademaker CMA, et al. Health care failure mode and effect analysis: a useful proactive risk analysis in a pediatric oncology ward. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Feb.15(1):58–64. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.014902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wetterneck TB, Skibinski KA, Schroeder ME, et al. Challenges with the performance of failure mode and effects analysis in healthcare organizations: an IV medication administration HFMEA. Annual Conference of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society; September 20–24, 2004; New Orleans, LA. The Human Factors and Ergonomics Society; [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wetterneck TB, Skibinski KA, Roberts TL, et al. Using failure mode and effects analysis to plan implementation of smart i.v. pump technology. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006 Aug. 1563:1528–1538. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burgmeier J. Failure mode and effect analysis: an application in reducing risk in blood transfusion. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2002 Jun.28(6):331–339. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(02)28033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeon J, Hyland S, Burns CM, et al. Challenges with applying FMEA to the process for reading labels on injectable drug containers. Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 51st Annual Meeting; Oct. 1–5, 2007; Baltimore, MA. pp. 735–739. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linkin DR, Sausman C, Santos L, et al. Applicability of healthcare failure mode and effects analysis to healthcare epidemiology: evaluation of the sterilization and use of surgical instruments. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Oct. 141(7):1014–1019. doi: 10.1086/433190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shebl NA, Franklin BD, Barber N. Is failure mode and effect analysis reliable? Journal of Patient Safety. 2009;5(2):1–9. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181a6f040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKelvey TC. How to improve the effectiveness of hazard and operability analysis. IEEE Transactions on Reliability. 1988 Jun.37(2):167–170. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith MJ, Sainfort PC. A balance theory of job design for stress reduction. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 1989;4(1):67–79. [Google Scholar]