Abstract

Highly enantioselective aminations of acyclic α-alkyl β-keto thioesters and trifluoroethyl α-methyl α-cyanoacetate (12) with as low as 0.05 mol % of a bifunctional cinchona alkaloid catalyst were established. This ability to afford highly enantioselectivity for the amination of α-alkyl β-carbonyl compounds renders the 6′-OH cinchona alkaloid-catalyzed amination applicable for the enantioselective synthesis of acyclic chiral compounds bearing N-substituted quaternary stereocenters. The synthetic application of this reaction is illustrated in a concise asymmetric synthesis of α-methylserine, a key intermediate previously utilized in the total synthesis of a small molecule immunomodulator, conagenin.

Keywords: bifunctional catalysis, asymmetric organocatalysis, cinchona alkaloids, chiral amines, quaternary stereocenters

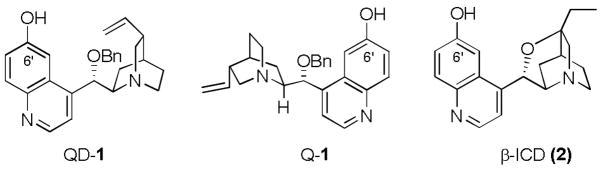

Biologically interesting compounds often contain nitrogen-substituted quaternary stereocenters. Thus, the construction of these quaternary stereocenters continues to attract great interests from synthetic chemists. Most of the catalytic asymmetric methods have been focused on enantioselective C-C bond forming reactions with nitrogen-containing prochiral starting materials, as exemplified by enantioselective Strecker reactions1,2 and electrophilic alkylations of glycine derivatives3,4. On the other hand, catalytic enantioselective C-N bond forming electrophilic aminations with metallic5 and organic catalysts6 recently emerged as another promising approach for the creation of N-substituted quaternary stereocenters. Bi-functional cinchona alkaloids 1 and 2 have been identified by us6b and Jørgensen6a, respectively, to be highly effective and general catalysts for the amination of αaryl α-cyanoacetates (Figure 1). Importantly, the ready accessibility of catalysts 1 from both quinidine and quinine allows these catalysts to provide facile access to both enantiomers of the amination product. In this paper we wish to document our recent progress in realizing highly enantioselective aminations of cyclic and acyclic α-alkyl β-carbonyl nucleophiles with 1.

Figure 1.

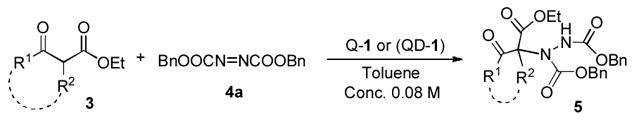

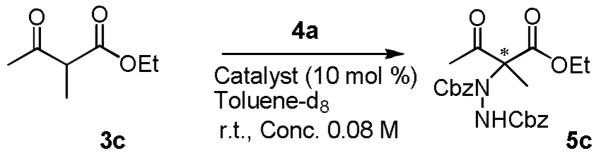

Our initial attempts to expand the scope of the 1-catalyzed amination began with an investigation of the reaction of α-substituted β-ketoesters 3 and dibenzyl azodicarboxylate (4a) in toluene in the presence of 1.

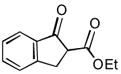

As summarized in Table 1, aminations of cyclic β-ketoesters 3a and 3b proceeded cleanly to furnish the the corresponding amination products in excellent yield and enantioselectivity with 1 mol % or less of 1 (entries 1–3). It is noteworthy that even with 0.1 mol % loading of Q-1 the excellent yield and enantioselectivity remain uncompromised (entry 2). In stark contrast, the amination of the less active acyclic β-ketoester 3c proceeded in less than 20% conversion and afforded the product in very poor ee even when 10 mol % of QD-1 was employed in the reaction (entry 4). A TLC analysis of the resulting reaction mixture revealed that catalyst QD-1 was completely consumed. In light of the report by Jørgensen and coworkers of a Fridel-Crafts amination of cuperidine with di-t-butyl diazocarboxylate,7 we suspected that QD-1 might undergo decomposition via a similar Fridel-Crafts reaction with dibenzyl azodicarboxylate (4a) in toluene. Indeed, QD-6 and QD-7 were isolated in 64% and 33% yield, respectively, from a reaction of QD-1 with 4a in toluene (Scheme 1).

Table 1.

Asymmetric Amination of β-Ketoesters 3 Catalyzed by 1a

Scheme 1.

Amination of QD-1

We further examined QD-6 and QD-7 as catalysts for the amination of 3c with 4a. As presented in Table 2, the former was found to be inactive while the latter afforded a reaction of low enantioselectivity and poor conversion (entries 2 and 3, Table 2). It was noticed that the poor results obtained from the QD-1-catalyzed amination of acyclic β-ketoester 3c resembled those afforded by QD-7, which suggested that the rapid decomposition of catalyst QD-1 to form QD-6 and QD-7 could be the cause of the observed poor enantioselectivity and activity afforded by QD-1 for the amination of 3c.

Table 2.

Amination of 3c with 4a Using Different Catalysts a

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst | Conv. (%)b / Time | ee (%)c |

| 1 | None (back ground) |

No product / 7d | N/A |

| 2 | QD-6 | No product / 7d | N/A |

| 3 | QD-7 | 14% / 7d | 10 |

| 4 | QD-1 | 19% / 7d | 17 |

Reaction was performed with 1.1 equiv of 3 and 1.0 equiv of 4a in toluene.

Conversions were determined by 1H NMR.

ee was determined using HPLC.

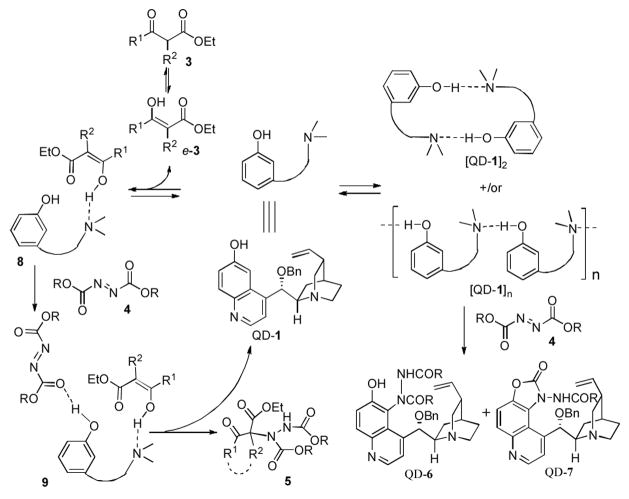

These experimental results also enable us to formulate a hypothesis, as described in Scheme 2, regarding the possible origin of the dramatic difference between the QD-1-catalyzed amination of cyclic-α-substituted β-ketoesters such as 3a–b and that of acyclic β-ketoesters 3c. In line with our proposed mechanism for 6′-OH cinchona alkaloid-catalyzed asymmetric conjugate additions,8 we postulated that QD-1 activated the β-ketoesters 3 via the formation of a hydrogen-bonding complex with the corresponding enol of 3 (e-3) (Scheme 2). However, QD-1 could also exist in the solution as a dimmer (QD-1)2 and/or an oligomer (QD-1)n, in which the hydrogen-bonding interaction between the 6′-OH and the quinuclidine nitrogen could activate the quinoline ring in QD-1 toward the Fridel-Crafts amination that decomposed QD-1 to form QD-6 and QD-7. While β-ketoesters 3 could exist in both the enol and the keto form, relative to the equilibrium between acyclic β-ketoester 3c and its corresponding enol e-3c, the equilibrium with a cyclic β-ketoesters such as 3a should be more favorably toward the enol e-3, which promoted the formation of the catalyst-substrate complexes 8 and 9 and, consequently, disfavored the formation of dimmer (QD-1)2 or oligomer (QD-1)n. This in turn should suppress the catalyst decomposition while enhancing the desirable enantioselective amination of 3.

Scheme 2.

Proposed Reaction Pathways of Catalyst 1

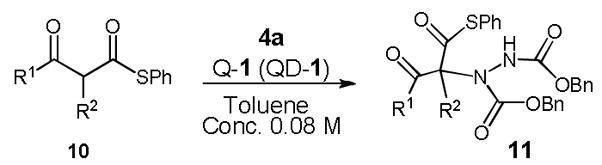

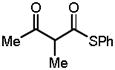

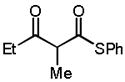

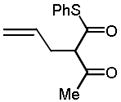

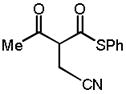

Guided by this analysis we began to investigate the amination of acyclic β-ketothioesters 10. We expected that 10, a class of acyclic β-carbonyl nucleophiles bearing a more acidic α-protons relative to those of the acyclic β-ketoesters,9 might undergo the 1-catalyzed enantioselective amination with significantly retarded catalyst decomposition. Accordingly, a reaction of dibenzyl azodicarboxylate (4a) and S-phenyl 2-methyl-3-oxothiobutyrate 10a with QD-1 in toluene was carried out at room temperature.11,12 Gratifyingly, with 1.0 mol % of Q-1, the reaction rapidly proceeded to completion in five minutes at root temperature to afford 11a in 92% yield and 95% ee (entry 1, Table 3). It is noteworthy that both the yield and enantioselectivity could be maintained at an excellent level even with only 0.05 mol % of Q-1 (entry 2). To our knowledge, this is one of the lowest catalyst loading documented for a highly enantioselective asymmetric reaction mediated by an organic catalyst. As summarized in Table 3, highly enantioselective aminations could be accomplished with various acyclic β-ketothioesters 10a–d. Importantly, variations of both the α-substituent (R1) and the ketone substituent (R2) were well tolerated by the catalysts. Moreover, the introduction of additional functional groups into the α-substituent is also accepted by the catalysts (entry 5). A cyclic β-ketothioester such as 10e was also found to be a good substrate (entries 6–7).

Table 3.

Asymmetric Amination of 10 catalyzed by 1a

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Substrate | Catalyst (mol %) |

Temp. (°C) |

Time | Yield b (%) |

eec (%) |

| 1 |

10a |

1(1) | RT(−60) | 5min(4h) | 92(95) | 95(91) |

| 2 | 0.05 | RT | 12h | 93 | 92 | |

| 3 |

10b |

2(1) | −40(−60) | 3h(27h) | 94(95) | 98(96) |

| 4 |

10c |

5(5) | −60(−60) | 3.5h(2.5h) | 91(90) | 98(95) |

| 5 |

10d |

10(10) | −60(−60) | 45min(15min) | 95(96) | 90(97) |

| 6 |

10e |

5(5) | −78(−78) | 15min(2h) | 94(95) | > 99(99) |

| 7 | 0.1 | RT | 19h | 92 | 96 | |

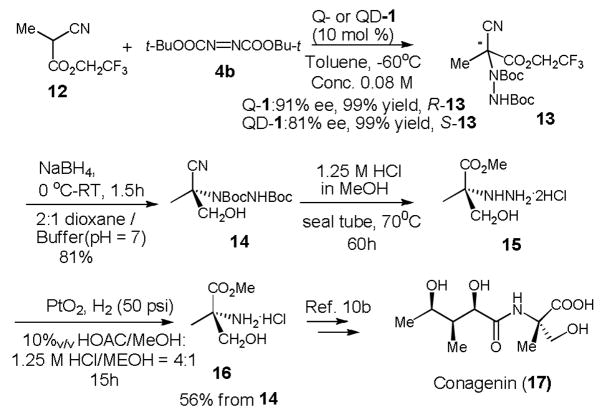

We previously reported that QD-1 promoted highly enantioselective aminations of various α-aryl α-cyanoacetates.6b However, the enantioselectivity drastically deteriorated for the amination with ethyl α-methyl α-cyanoacetate, an α-alkyl α-cyanoacetate, and furnished the corresponding amination product in only 35% ee and in 75% yield. It is noteworthy that Jorgensen and coworkers reported similarly low enantioselectivity (27% ee) for the amination of ethyl α-methyl α-cyanoacetate with isocuperidine (2) as the catalyst.6a Our success in realizing highly enantioselective aminations of β-ketothioesters 10 suggested that the 1-catalyzed asymmetric amination with an α-alkyl α-cyanoacetate bearing a more acidic α-hydrogen, such as 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl α-methyl α-cyanoacetate (12), might occur with improved enantioselectivity. To our delight, aminations of 12 and di-t-butyl azodicarboxylate (4b) with Q- and QD-1 generated the desirable product 13 in 91% and 81% ee, respectively, and in virtually quantitative yield (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

After the expansion of the substrate scope described above, the 1-catalyzed enantioselective amination has become applicable to acyclic α-alkyl β-carbonyl compounds. Consequently, it provides a useful method for the asymmetric synthesis of acyclic chiral aliphatic compounds containing N-substituted quaternary centers. Taking advantage of this new capacity of the 1-catalyzed amination, we developed a concise synthesis of methyl (S)-α-methylserinate 16 (Scheme 3). Thisα,α-disubstituted amino acid was used as a key intermediate in a total synthesis of conagenin 17, a small molecule immunomodulator that enhances the proliferation and lymphokine production of activated T cells.10

In conclusion, we have realized highly enantioselective aminations of acyclic α-alkyl β-keto-thioesters and trifluoroethyl α-methyl α-cyanoacetate (12), thereby significantly expanded the substrate scope of the 6′-OH cinchona alkaloid-catalyzed aminations. Consequently, as illustrated in its application in the asymmetric synthesis of α-methylserine 16, this efficient and operationally simple catalytic asymmetric amination could be applied to facilitate the demanding but important task of constructing N-substituted quaternary stereocenters bearing aliphatic substituents in acyclic compounds.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of NIH (GM-61591) and Daiso Inc.

References

- 1.For reviews, see: Gröger H. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2795. doi: 10.1021/cr020038p.Spino C. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:1764. doi: 10.1002/anie.200301686.

- 2.(a) Vachal P, Jacobsen EN. Org Lett. 2000;2:867. doi: 10.1021/ol005636+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vachal P, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:10012. doi: 10.1021/ja027246j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Masumoto S, Usuda H, Suzuki M, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:5634. doi: 10.1021/ja034980+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kato N, Suzuki M, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:3147. [Google Scholar]; (e) Kato N, Suzuki M, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:3153. [Google Scholar]; (f) Kato N, Tomita D, Maki K, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J Org Chem. 2004;69:6128. doi: 10.1021/jo049258o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Kato N, Mita T, Kanai M, Therrien B, Kawano M, Yamaguchi K, Danjo H, Sei Y, Sato A, Furusho S, Shibasaki M. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6768. doi: 10.1021/ja060841r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Wang J, Hu XL, Jiang J, Gou SH, Huang X, Liu XH, Feng XM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:8468. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Hou Z, Wang J, Liu X, Feng X. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:4484. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For reviews, see: Maruoka K, Ooi T. Chem Rev. 2003;103:3013. doi: 10.1021/cr020020e.O’Donell MJ. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:506. doi: 10.1021/ar0300625.Hashimoto T, Maruoka K. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5656. doi: 10.1021/cr068368n.

- 4.(a) Ooi T, Takeuchi M, Kameda M, Maruoka K. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:5228. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ooi T, Takeuchi M, Maruoka K. Synthesis. 2001:1716. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ooi T, Takeu-chi M, Ohara D, Maruoka K. Synlett. 2001:1185. [Google Scholar]; (d) Jew S-s, Jeong B-S, Lee J-H, Yoo M-S, Lee Y-J, Park B-s, Kim MG, Park H-g. J Org Chem. 2003;68:4514. doi: 10.1021/jo034006t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Marigo M, Juhl K, Jorgensen KA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:1367. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mashiko T, Hara K, Tanaka D, Fujiwara Y, Kumagai N, Shibasaki M. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11342. doi: 10.1021/ja0752585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mashiko T, Kumagai N, Shibasaki M. Org Lett. 2008;10:2725. doi: 10.1021/ol8008446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Saaby S, Bella M, Jørgensen KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8120. doi: 10.1021/ja047704j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu X, Li H, Deng L. Org Lett. 2005;7:167. doi: 10.1021/ol048190w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Xu X, Yabuta T, Yuan P, Take-moto Y. Synlett. 2006:137. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandes S, Belle M, Kjærsgaard A, Jorgensen KA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:1147. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Li H, Wang Y, Tang L, Deng L. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9906. doi: 10.1021/ja047281l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li H, Wang Y, Tang L, Wu F, Liu X, Guo C, Foxman BM, Deng L. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;44:105. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The β-ketothioester is more acidic than the corresponding β-ketoester, see: Bordwell FG, Fried HE. J Org Chem. 1991;56:4218.Bordwell FG. Acc Chem Res. 1988;21:456.Bell RP. The Proton in Chemistry. Ithica: Cornell University Press; 1959.

- 10.(a) Yamashita T, Iijima M, Nakamura H, Isshiki K, Naganawa H, Hattori S, Hamada M, Ishizuka M, Takeuchi T, Iitaka Y. J Antibiot. 1991;44:557. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sano S, Miwa T, Hayashi K, Nozaki K, Ozaki Y, Nagao Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:4029. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Experimental procedure for the asymmetric amination of 3 (or 10) with 4a catalyzed by Q-1: A suspension of Q-1 in toluene (2.0 mL) was subjected to ultrasound until no chunky solid was visible (c.a. 15 min). The resulting mixture was heated at 110 °C until a clear solution was formed (10–15 min). While it was still hot, the solution was allowed to pass a cotton plug to remove any trace amount of insoluble residue and then cooled to room temperature. Then 3 (or 10) (0.22 mmol, 1.1 eq) was added. This mixture was stirred at indicated temperature and a solution of 4a (0.50 M, 0.40 mL, 0.20 mmol) was added dropwise in 5–10 min. The stirring was continued until the color of the solution turned from yellow to colorless (or at indicated time) and the amination product was isolated by flash chromatography separation.

- 12.Experimental procedure for the asymmetric amination of 3 (or 10) with 4a catalyzed by QD-1: To a solution of 3 or 10 (0.22 mmol, 1.1 eq) and QD-1 in toluene (2.0 mL) at indicated temperature under stirring, a solution of 4a in toluene (0.50 M, 0.40 mL, 0.20 mmol) was added dropwise in5–10 min. The resulting reaction mixture was stirred until the color of the solution turned from yellow to colorless (or at indicated time), and the aminationproduct was isolated by flash chromatography.