Abstract

An algorithm for use of Prasugrel (Effient) in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital is presented. Our algorithm, which is in the process of being implemented, is consistent with published and generally accepted standards of care and is based on data from the pivotal Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TRITON-TIMI) 38, which compared clopidogrel to prasugrel in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients undergoing PCI. Areas of focus include analysis of the benefit of prasugrel over clopidogrel in ACS patients and appropriate selection of patients for prasugrel treatment.

Keywords: dual antiplatelet therapy, prasugrel, clopidogrel, acute coronary syndromes, clinical pathways

Introduction

Current guidelines recommend administration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), which includes aspirin and a platelet P2Y12 adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonist following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).1 These recommendations are based on data that compared to aspirin, or aspirin in combination with warfarin, DAPT reduces ischemic events following elective PCI for stable angina2 and urgent PCI for acute coronary syndromes (ACS).3, 4 Clopidogrel is the most widely used P2Y12 inhibitor because it is better tolerated and has fewer side effects compared to the first generation thienopyridine, ticlopidine. Clopidogrel is a prodrug that undergoes hepatic cytochrome P450 system (CYP) activation to form the active metabolite. Only 10% of clopidogrel is converted to the active metabolite because esterases shunt the majority of the drug to an inactive form before conversion occurs.5 Because of the time required for prodrug conversion to active metabolite, peak onset of clopidogrel action occurs up to 6 hours after administration of the loading dose.

There is considerable interindividual variability in the onset of action and the degree of platelet inhibition achieved with clopidogrel, and high residual platelet activity following clopidogrel treatment (hyporesponsiveness) is associated with adverse cardiovascular (CV) events in PCI patients.6–10 Clopidogrel hyporesponsiveness is related to clinical and genetic factors that alter pharmacokinetics10 and diabetes, congestive heart failure (CHF), and obesity are associated with reduced clopidogrel efficacy.6, 11 Several common polymorphisms that reduce CYP activity decrease hepatic activation of clopidogrel. Among persons treated with clopidogrel, carriers of reduced-function CYP2C19 alleles have significantly lower levels of active metabolite, diminished platelet inhibition, and higher rates of adverse cardiovascular events and stent thrombosis following PCI.10 The prevalence of the CYP2C19 polymorphism in the general population is significant and ranges from 30–60% depending on ethnic background, and the prevalence of being a homozygote for a reduced function polymorphism ranges from 2–14%.12–15 Furthermore, medications that inhibit CYP activity, such as specific proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), reduce clopidogrel conversion and have the potential to decrease clopidogrel efficacy by diminishing clopidogrel conversion to the active metabolite.16 The potential for reduced clinical efficacy of clopidogrel in patients with CYP polymorphisms or in patients co-treated with certain PPIs has recently been addressed by the FDA in updated black box warnings that have been added to the clopidogrel package insert.15

Several recent studies have demonstrated that clopidogrel hyporesponsiveness can be partially overcome by increasing the dose from standard dosing (300mg load and 75mg daily) to high loading (600 or 900mg) and/or high maintenance (150mg daily) dosing. These elevated doses have been shown to shorten the onset of action, reduce interindividual variability, and improve early outcomes without increasing bleeding.17, 18 Recently, high loading and short term (7-day) high maintenance dose clopidogrel was associated with improved 30 day cardiovascular outcomes compared to standard therapy (300mg load and 75mg daily) without increase in TIMI major bleeding in the PCI subgroup of the Current OASIS 7 study.19 There was however a significant increase in severe and major bleeding using CURRENT bleeding criteria. Results from OASIS 7 should be interpreted cautiously because the benefit of high loading and maintenance dose clopidogrel was negative for the entire study cohort, and PCI subgroup analysis should be regarded as hypothesis generating. Further investigation in randomized trials will be required to definitively evaluate the efficacy and safety of high loading and maintenance dose clopidogrel following PCI.

Hyporesponsiveness does not appear to be a problem with many next generation P2Y12 antagonists such as prasugrel that are more potent, have faster onset of action (<1hour), and have minimal interindividual variability. Prasugrel is also a prodrug that requires a single CYP-dependent conversion to the active metabolite,5, 12, 20 but in contrast to clopidogrel, prasugrel has more efficient absorption and rapid conversion to active metabolite.20 Additionally, common functional CYP genetic variants do not affect prasugrel active drug metabolite levels, and prasugrel provides more uniform and more potent inhibition of platelet aggregation compared to clopidogrel.12, 21 Prasugrel was approved in 2009 by the FDA as an alternative to clopidogrel for DAPT in ACS patients undergoing PCI based largely on the results from the Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TRITON-TIMI) 38, which compared clopidogrel and prasugrel in ACS patients undergoing PCI.22

Prasugrel Versus Clopidogrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes: TRITON-TIMI 38 Design and Results

TRITON-TIMI 38 compared regimens of prasugrel and clopidogrel to test the hypothesis that an antiplatelet agent with greater potency and less-variable response would reduce ischemic events compared to standard-dose clopidogrel.22 The study randomized 13,608 patients with moderate-to-high-risk ACS (10,074 with unstable angina or non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction and 3534 with ST-elevation myocardial infarction) undergoing PCI to prasugrel (60-mg loading, 10-mg QD) or clopidogrel (300-mg loading dose, 75-mg QD) for a duration of 6 to 15 months (median duration 14 months). The major efficacy endpoint was death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke (Table 1). The major safety end point was non-CABG TIMI major bleeding (Table 2). Major exclusion criteria included increased risk of bleeding, anemia, thrombocytopenia, a history of pathological intracranial findings, or the use of any thienopyridine within 5 days of enrollment. The dosing strategy in the study was such that a loading dose of study medication (60 mg of prasugrel or 300 mg of clopidogrel) was administered, in a double-blind manner, anytime between randomization and 1 hour after leaving the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Since the protocol was designed as a trial of ACS patients who were undergoing PCI, the coronary anatomy had to be known to be suitable for PCI before randomization for patients with unstable angina and non ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). If the coronary anatomy was previously known or primary PCI for ST-elevation myocardial infarction was planned, pretreatment with the study drug was permitted up to 24 hours before PCI. ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients undergoing urgent PCI were treated with the study drug any time after consent and randomization. In the trial, one third of the STEMI patients were preloaded with study drug prior to PCI and the rest of the patients received study drug during the PCI or up to one hour after the PCI was completed.23 Data are not currently available to quantify the number of STEMI patients that might have received study drug prior to defining the coronary anatomy with diagnostic catheterization.

Table 1.

Major Efficacy End Points in the Overall Cohort at 15 Months.*

| End Point | Prasugrel (N=6813) |

Clopidogrel (N=6795) |

Hazard Ratio for Prasugrel (95% CI) |

P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. of patients (%) | ||||

| Death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke (primary end point) | 643 (9.9) | 781 (12.1) | 0.81 (0.73–0.90) | <0.001 |

| Death from cardiovascular causes | 133 (2.1) | 150 (2.4) | 0.89 (0.70–1.12) | 0.31 |

| Nonfatal MI | 475 (7.3) | 620 (9.5) | 0.76 (0.67–0.85) | <0.001 |

| Nonfatal stroke | 61 (1.0) | 60 (1.0) | 1.02 (0.71–1.45) | 0.93 |

| Death from any cause | 188 (3.0) | 197 (3.2) | 0.95 (0.78–1.16) | 0.64 |

| Death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal MI, or urgent target-vessel revascularization | 652 (10.0) | 798 (12.3) | 0.81 (0.73–0.89) | <0.001 |

| Death from any cause, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke | 692 (10.7) | 822 (12.7) | 0.83 (0.75–0.92) | <0.001 |

| Urgent target-vessel revascularization | 156 (2.5) | 233 (3.7) | 0.66 (0.54–0.81 | <0.001 |

| Death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or rehospitalization for ischemia | 797 (12.3) | 938 (14.6) | 0.84 (0.76–0.92) | <0.001 |

| Stent thrombosis‡ | 68 (1.1) | 142 (2.4) | 0.48 (0.36–0.64) | <0.001 |

The percentages are Kaplan-Meier estimates of the rate of the end point at 15 months. Patients could have had more than one type of end point. Death from cardiovascular causes and fatal bleeding (Table 2) are not mutually exclusive, since intracranial hemorrhage and death after cardiovascular procedures that were complicated by fatal bleeding were included in both end points. MI denotes myocardial infarction.

P values were calculated with the use of the log-rank test. The prespecified analysis for the primary end point used the Gehan-Wilcoxon test, for which the P value was less than 0.001.

Stent thrombosis was defined as definite or probable thrombosis, according to the Academic Research Consortium; the numbers of patients at risk were all patients whose index procedure included at least one intracoronary stent: 6422 patients in each of the two treatment groups.

Used with permission, Wiviott, S.D. et. al, Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2001–2015. Copyright ©2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Table 2.

Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Bleeding End Points in the Overall Cohort at 15 Months.*

| End Point | Prasugrel (N=6741) |

Clopidogrel (N=6716) |

Hazard Ratio for Prasugrel (95% CI) |

P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. of patients (%) | ||||

| Non-CABG-related TIMI major bleeding (key safety end point) | 146 (2.4) | 111 (1.8) | 1.32 (1.03–1.68) | 0.03 |

| Related to instrumentation | 45 (0.7) | 38 (0.6) | 1.18 (0.77–1.82) | 0.45 |

| Spontaneous | 92 (1.6) | 61 (1.1) | 1.51 (1.09–2.08) | 0.01 |

| Related to trauma | 9 (0.2) | 12 (0.2) | 0.75 (0.32–1.78) | 0.51 |

| Life-threatening† | 85 (1.4) | 56 (0.9) | 1.52 (1.08–2.13) | 0.01 |

| Related to instrumentation | 28 (0.5) | 18 (0.3) | 1.55 (0.86–2.81) | 0.14 |

| Spontaneous | 50 (0.9) | 28 (0.5) | 1.78 (1.12–2.83) | 0.01 |

| Related to trauma | 7 (0.1) | 10 (0.2) | 0.70 (0.27–1.84) | 0.47 |

| Fatal | 21 (0.4) | 5 (0.1) | 4.19 (1.58–11.11) | 0.002 |

| Nonfatal‡ | 64 (1.1) | 51 (0.9) | 1.25 (0.87–1.81) | 0.23 |

| Intracranial | 19 (0.3) | 17 (0.3) | 1.12 (0.58–2.15) | 0.74 |

| Major or minor TIMI bleeding | 303 (5.0) | 231 (3.8) | 1.31 (1.11–1.56) | 0.002 |

| Bleeding requiring transfusion§ | 244 (4.0) | 182 (3.0) | 1.34 (1.11–1.63) | <0.001 |

| CABG-related TIMI major bleeding¶ | 24 (13.4) | 6 (3.2) | 4.73 (1.90–11.82) | <0.001 |

The data shown are for patients who received at least one dose of the study drug and for end points occurring within 7 days after the study drug was discontinued or occurring within a longer period if the end point was believed by the local investigator to be related to the use of the study drug. Percentages are Kaplan-Meier estimates of the rate of the end point at 15 months. Patients could have had more than one type of end point. CABG denotes coronary-artery by-pass grafting.

The most frequent sites of life-threatening bleeding were gastrointestinal sites, intracranial sites, the puncture site, and retroperitoneal sites.

One patient in the clopidogrel group had a fatal gastrointestinal hemorrhage while receiving the study medication, but hemoglobin testing was not performed and, therefore, the criteria for TIMI major bleeding (including life-threatening and fatal bleeding) could not be applied and the data do not appear in this table.

Transfusion was defined as any transfusion of whole blood or packed red cells

For major bleeding related to CABG, the total number of patients were all patients who had received at least one dose of prasugrel or clopidogrel before undergoing CABG: 179 and 189, respectively. The ratio is the odds ratio, rather than the hazard ratio, and was evaluated with the use of the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test.

Used with permission, Wiviott, S.D. et. al, Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2001–2015. Copyright ©2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

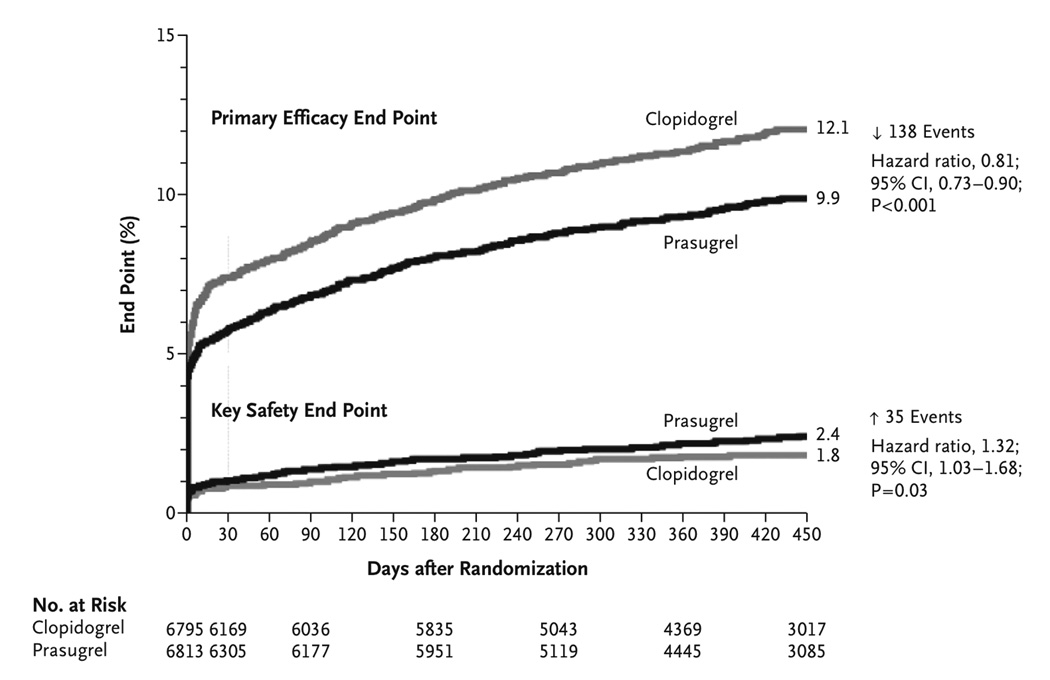

The primary efficacy end point (death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke) occurred in 9.9% of patients receiving prasugrel and 12.1% of patients receiving clopidogrel (hazard ratio (HR) for prasugrel vs. clopidogrel, 0.81; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73 to 0.90; P<0.001)(Figure 1). There were significant reductions in the prasugrel group in the rates of myocardial infarction (prasugrel, 7.4% vs. clopidogrel, 9.7%; P<0.001), urgent target-vessel revascularization (prasugrel, 2.5% vs. clopidogrel, 3.7%; P<0.001), and stent thrombosis (prasugrel, 1.1% vs. clopidogrel, 2.4%; P<0.001). TIMI Major bleeding not associated with CABG was observed in 2.4% of patients receiving prasugrel and in 1.8% of patients receiving clopidogrel (HR for prasugrel vs. clopidogrel, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.68; P = 0.03). Also greater in the prasugrel group was the rate of life-threatening bleeding (prasugrel, 1.4% vs. clopidogrel, 0.9%; P = 0.01), which included nonfatal bleeding (prasugrel, 1.1% vs. clopidogrel, 0.9%; HR, 1.25; P = 0.23) and fatal bleeding (prasugrel, 0.4% vs. clopidogrel, 0.1%; P = 0.002). Summarizing the results of TRITON, for 1000 ACS patients treated with PCI, prasugrel vs. clopidogrel therapy (median duration 14.5 months) would prevent 22 major vascular events (mostly driven by nonfatal MI, Table 1) and cause 6 major hemorrhages, including 2–3 fatal bleeds. Post-hoc subgroup analysis identified less clinical efficacy and greater bleeding in patients with prior history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, in elderly patients (age ≥ 75 years), in patients with low body weight (<60 kg), and in patients undergoing urgent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)(Table 3). Importantly, TIMI major CABG-related bleeding rates were 13.4% with prasugrel vs. 3.2% with clopidogrel (Table 2). Increased risk of bleeding in these subgroups resulted in an FDA black box warning stating that prasugrel should not be prescribed to patients with any history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) or to patients with severe liver dysfunction.24 In addition, prasugrel is not recommended for elderly patients (age > 75 years) as this subgroup had increased risk of fatal and intracranial bleeding with uncertain benefit except in high-risk subsets (those with history of diabetes or prior MI).24 Prasugrel should also be avoided with concomitant use of medications that increase bleeding risk (i.e. warfarin) and should be used with caution in patients with low body weight (less than 60 kg). Reanalysis of the TRITON study demonstrated that when prasugrel is used in selected patients (age <75, weight ≥60kg, no history of prior TIA/stroke), the risk of the non-CABG TIMI major bleeding is improved (prasugrel, 2.0% vs. clopidogrel, 1.5%; HR, 1.24; P=0.17) while reduction in the primary CV endpoint is maintained (prasugrel, 8.3% vs. clopidogrel, 11.0%; HR, 0.75; P<0.001).25

Figure 1. Cumulative Kaplan–Meier Estimates of the Rates of Key Study End Points during the Follow-up Period.

Data for the primary efficacy end point (death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction [MI], or nonfatal stroke) (top) and for the key safety end point (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction [TIMI] major bleeding not related to coronary-artery bypass grafting) (bottom) during the full follow-up period. The hazard ratio for prasugrel, as compared with clopidogrel, for the primary efficacy end point at 30 days was 0.77 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.67–0.88; P<0.001) and at 90 days was 0.80 (95% CI, 0.71 to 0.90; P<0.001). Used with permission, Wiviott, S.D. et. al, Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2001–2015. Copyright ©2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Table 3.

Risk factors for bleeding with Prasugrel

| Patients with active pathological bleeding, history of transient ischemic attack, history of stroke (Prasugrel contraindicated) |

| Patients over 75 years old |

| Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery (when possible, discontinue prasugrel at least 7 days prior to any surgery). |

Additional risk factors for bleeding include:

|

The prasugrel dosing strategy examined in TRITON-TIMI 38 was a 60mg loading dose and a maintenance dose of 10mg per day. In patients at high risk for bleeding (body weight <60kg), use of a 5mg maintenance dose can be considered as outlined in the FDA-approved package insert.24 Support for a 5mg prasugrel regimen is derived from small dosing studies that evaluated platelet inhibition rather than clinical events. Outcome studies and clinical experience with the 5mg dose are currently lacking. The median duration of prasugrel therapy was 14.5 months in TRITON-TIMI 38. Current ACC/AHA consensus statements recommend DAPT for 12 months following PCI with drug eluting stents (DES).1 Continuation of prasugrel after the 12-month mark is at clinician’s discretion. The DAPT trial, a multi-center clinical trial to evaluate the optimal duration of DAPT (12 months compared to 30 months) began enrollment in October 2009 however data are not expected for several years.26 It should be noted that 30 day landmark analysis of patients in TRITON-TIMI 38 demonstrated that for the primary CV end point, 68% of the events avoided with prasugrel compared with clopidogrel occurred during the highest risk period of the first 30 days after the index ACS/PCI event,25 while 74% of the excess bleeding events occurred during the longer maintenance period from 30 to 450 days.27 Protocols for routine transitioning of patients from prasugrel to clopidogrel within the initial 12 months following ACS/PCI have not been studied. To date, randomized clinical studies have not directly assessed the relative efficacy and bleeding risk of prasugrel vs. high loading dose (600mg or 900mg) and/or high maintenance dose (150mg daily) clopidogrel regimens.

Prasugrel Prescribing Algorithm

The primary goal of the prasugrel prescribing strategy developed at Brigham and Women’s Hospital is to harness the increased antiplatelet efficacy of prasugrel vs. clopidogrel for preventing ischemic events, while minimizing the increased bleeding risk associated with prasugrel therapy. To minimize the risk of CABG-related TIMI major bleeding, the prescribing strategy outlined below is designed to defer use of prasugrel if there is the possibility that a patient could require urgent CABG. Thus, the preferred timing to administer the prasugrel load is after the coronary anatomy has been defined by diagnostic catheterization. For the purposes of guiding clopidogrel and prasugrel administration, ACS patients are stratified into two groups based on the anticipated delay between their presentation and start of the cardiac catheterization procedure as outlined below and in Figure 2. Regardless of whether prasugrel or clopidogrel is administered, we have opted to prescribe DAPT for 12 months following PCI in accordance with ACC/AHA recommendations.1, 22 We have chosen 12 months despite the fact that the median duration of therapy in TRITON-TIMI 38 was 14 months. In some cases, very high-risk patients (left main stenting, prior stent thrombosis, complex bifurcation stenting) are maintained on DAPT indefinitely however we have no experience with extended duration prasugrel at this time.

Figure 2. Prasugrel Administration Algorithm.

For the purposes of guiding prasugrel administration, ACS patients are stratified into two groups based on the anticipated delay between their presentation and start of the cardiac catheterization. Diagnostic cardiac catheterization, Dx cath; percutaneous coronary intervention, PCI; transient ischemic attack, TIA; thienopyridine, TP. Patients with renal dysfunction, body weight < 60kg, and history of gastrointestinal bleeding are at higher risk of bleeding, and bleeding risk is elevated with concomitant use of other medications that increase the rate of bleeding. *In STEMI cases where cardiology determines it is highly unlikely that the patient will require CABG, upstream prasugrel loading prior to diagnostic angiogram can be considered on an individual basis. **The decision to load patients with prasugrel when switching from clopidogrel can be made on a case by case basis after considering the potential ischemic benefit and bleeding risk of a given patient.

Prescribing strategy for STEMI or ACS patients undergoing cardiac catheterization within six hours of initial presentation

For patients that are eligible for prasugrel therapy, standard aspirin and intravenous (i.v.) antithrombotic therapy (unfractionated heparin or bivalirudin) should be administered per hospital ACS protocol. Because of the brief interval (<6h) between presentation and catheterization, neither clopidogrel nor prasugrel will be routinely administered until the coronary anatomy is defined by diagnostic cardiac catheterization. Once it is determined that the patient will be treated with PCI rather than medical therapy or CABG, the patient should be loaded with prasugrel prior to initiation of PCI. Because of the increased efficacy and rapid onset of peak platelet inhibition with prasugrel (≈30min), the strategy of defining coronary anatomy and loading before initiation of PCI will achieve more effective platelet inhibition within a similar or potentially faster timeframe compared to pre-procedural clopidogrel treatment in which inhibition peaks 3–6 hours after loading. In STEMI cases where cardiology determines it is highly unlikely that the patient will require CABG, upstream prasugrel loading prior to diagnostic angiogram can be considered on an individual basis.

Prescribing strategy for ACS patients not proceeding to cardiac catheterization within six hours of initial presentation

Trial data support clopidogrel preloading ACS patients undergoing catheterization or PCI as a mechanism to enhance platelet inhibition and reduce adverse cardiac events (reviewed28). Frequently patients with low acuity ACS, unstable angina (UA) or NSTEMI will be referred for non-emergent catheterization greater than 6 hours after their initial presentation. In these patients, aspirin and antithrombotic therapy (i.v. unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin) if indicated, should be administered according to hospital ACS protocol. At the discretion of the cardiologist, the patient can also be treated with clopidogrel (600mg load and 75mg daily) during the interval before cardiac catheterization. If the decision is made to proceed with PCI, patients not pretreated with clopidogrel should be loaded with 60mg of prasugrel prior to initiation of PCI. If the patient has been pretreated with clopidogrel then a switch to prasugrel should occur at the next scheduled dosing interval for clopidogrel with interchange of prasugrel for clopidogrel at the standard prasugrel maintenance dose of 10mg. Although clopidogrel loading and switching to prasugrel is not directly addressed by clinical trial outcome data, the rationale to dose the next day is in part derived from several small pharmacodynamic switching studies.29–33 Notably, the FDA-approved prasugrel package insert addresses the process of switching patients from chronic clopidogrel to prasugrel stating, “Discontinuing clopidogrel 75 mg and initiating prasugrel 10 mg with the next dose resulted in increased inhibition of platelet aggregation, but not greater than that typically produced by a 10 mg maintenance dose of prasugrel alone.”24 Switching from steady state clopidogrel therapy to prasugrel can be accomplished with or without administration of a loading dose of prasugrel. Dosing studies in healthy patients that examined switching from clopidogrel to prasugrel without prasugrel loading demonstrate gradual increase in platelet inhibition over 36–48 hours. Switching from clopidogrel to prasugrel with a 60mg prasugrel load results in a rapid (<30min) increase in platelet inhibition, which is stronger than that achieved with clopidogrel 75mg daily and slightly stronger than that achieved with the 10mg maintenance dose of prasugrel.30, 31 The decision to load patients with prasugrel when switching from clopidogrel can be made on a case by case basis after considering the potential ischemic benefit and bleeding risk of a given patient.

Prescribing strategy for ACS patients presenting on maintenance dose clopidogrel

For patients presenting with an ACS on standard dose clopidogrel, once the decision is made to treat with prasugrel, switching from steady state clopidogrel to prasugrel can be accomplished at the next dose as outlined above. If it is uncertain whether the patient is clopidogrel responsive, or if there is uncertainty about clopidogrel compliance, then strong consideration should be given to administering a loading dose of prasugrel at the time of PCI.

Emergency Room ACS treatment protocols and ADP Receptor Antagonist Administration

In order to maximize the ability to treat eligible patients with prasugrel while avoiding prasugrel in patients that will require CABG, STEMI or ACS patients that are going directly to cardiac catheterization in less than six hours will not routinely be given an ADP receptor antagonist if the patient is eligible for prasugrel. Prasugrel will be given once the coronary anatomy is defined prior to initiation of PCI. If the ACS patient is to be admitted with the plan for cardiac catheterization greater than 6 hours after presentation, clopidogrel can be administered at the discretion of cardiology if clinically indicated (as outlined above).

Potential Additional Uses of Prasugrel

Outcome studies comparing clopidogrel to prasugrel in elective PCI have not been completed and data examining the safety and efficacy of prasugrel in elective PCI are lacking. However, at the discretion of the practitioner, prasugrel can be considered for use in the following subsets of high-risk patients treated with elective PCI if the patient is likely to benefit from more potent antiplatelet therapy; (1) Patients for whom stent thrombosis would be catastrophic or lethal, such as unprotected left main coronary stenting or last patent coronary vessel, (2) Patients at high risk for stent thrombosis, including complicated bifurcation stenting, coronary disease requiring multiple stents, or stenting of long artery segments, (3) Patients with a history of stent thrombosis, and (4) patients in whom genotype testing demonstrates homozygous reduced-function CYP alleles and/or platelet function testing demonstrates clopidogrel hyporesponsiveness. When considering prasugrel after elective PCI, clinicians need to carefully assess bleeding risk as the ischemic benefit is likely lower in elective vs. ACS settings, and therefore the margin for net clinical benefit may be narrower. Several clinical studies are underway to assess prasugrel vs. clopidogrel in elective PCI patients.

Summary

Prasugrel is a rapid-acting, potent antiplatelet agent, which has minimal interindividual variability. When administered to ACS patients undergoing PCI, prasugrel reduces ischemic CV endpoints but increases bleeding compared to clopidogrel. In order to balance antiplatelet efficacy for preventing ischemic events and safety with regard to the increased risk of bleeding, we recommend defining coronary anatomy with diagnostic cardiac catheterization prior to treating with prasugrel as method of minimizing CABG-related TIMI major bleeding. Although clinical studies have not directly evaluated prasugrel in elective PCI, prasugrel may be considered in elective PCI patients that have high-risk coronary anatomy, homozygous reduced-function CYP alleles, or clopidogrel hyporesponsiveness measured by platelet function testing after careful assessment of the individual patient’s bleeding risk.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by a Jorge Paulo Lemann Cardiovascular grant to J.M. and grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to K.C. (1K08HL086672), a Michael Lerner Young Investigator Award to K.C., a Harris Family Foundation Award to K.C.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure:

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, Jr, King SB, 3rd, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Bailey SR, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Casey DE, Jr, Green LA, Hochman JS, Jacobs AK, Krumholz HM, Morrison DA, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Peterson ED, Sloan MA, Whitlow PL, Williams DO. 2009 focused updates: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2004 guideline and 2007 focused update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI guidelines on percutaneous coronary intervention (updating the 2005 guideline and 2007 focused update) a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(23):2205–2241. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Mann JT, 3rd, Fry ET, DeLago A, Wilmer C, Topol EJ. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2002;288(19):2411–2420. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, Bertrand ME, Lewis BS, Natarajan MK, Malmberg K, Rupprecht H, Zhao F, Chrolavicius S, Copland I, Fox KA. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet. 2001;358(9281):527–533. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05701-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, Lopez-Sendon JL, Montalescot G, Theroux P, Lewis BS, Murphy SA, McCabe CH, Braunwald E. Effect of clopidogrel pretreatment before percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with fibrinolytics: the PCI-CLARITY study. JAMA. 2005;294(10):1224–1232. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.10.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farid NA, Kurihara A, Wrighton SA. Metabolism and disposition of the thienopyridine antiplatelet drugs ticlopidine, clopidogrel, and prasugrel in humans. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;50(2):126–142. doi: 10.1177/0091270009343005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price MJ, Endemann S, Gollapudi RR, Valencia R, Stinis CT, Levisay JP, Ernst A, Sawhney NS, Schatz RA, Teirstein PS. Prognostic significance of post-clopidogrel platelet reactivity assessed by a point-of-care assay on thrombotic events after drug-eluting stent implantation. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(8):992–1000. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buonamici P, Marcucci R, Migliorini A, Gensini GF, Santini A, Paniccia R, Moschi G, Gori AM, Abbate R, Antoniucci D. Impact of platelet reactivity after clopidogrel administration on drug-eluting stent thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(24):2312–2317. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcucci R, Gori AM, Paniccia R, Giusti B, Valente S, Giglioli C, Buonamici P, Antoniucci D, Abbate R, Gensini GF. Cardiovascular death and nonfatal myocardial infarction in acute coronary syndrome patients receiving coronary stenting are predicted by residual platelet reactivity to ADP detected by a point-of-care assay: a 12-month follow-up. Circulation. 2009;119(2):237–242. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.812636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuisset T, Frere C, Quilici J, Barbou F, Morange PE, Hovasse T, Bonnet JL, Alessi MC. High post-treatment platelet reactivity identified low-responders to dual antiplatelet therapy at increased risk of recurrent cardiovascular events after stenting for acute coronary syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(3):542–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, Shen L, Hockett RD, Brandt JT, Walker JR, Antman EM, Macias W, Braunwald E, Sabatine MS. Cytochrome p-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(4):354–362. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hochholzer W, Trenk D, Fromm MF, Valina CM, Stratz C, Bestehorn HP, Buttner HJ, Neumann FJ. Impact of Cytochrome P450 2C19 Loss-of-Function Polymorphism and of Major Demographic Characteristics on Residual Platelet Function After Loading and Maintenance Treatment With Clopidogrel in Patients Undergoing Elective Coronary Stent Placement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(22):2427–2434. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, Shen L, Hockett RD, Brandt JT, Walker JR, Antman EM, Macias WL, Braunwald E, Sabatine MS. Cytochrome P450 genetic polymorphisms and the response to prasugrel: relationship to pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and clinical outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119(19):2553–2560. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.851949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sibbing D, Stegherr J, Latz W, Koch W, Mehilli J, Dorrler K, Morath T, Schomig A, Kastrati A, von Beckerath N. Cytochrome P450 2C19 loss-of-function polymorphism and stent thrombosis following percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(8):916–922. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim IS, Choi BR, Jeong YH, Kwak CH, Kim S. The CYP2C19*2 and CYP2C19*3 polymorphisms are associated with high post-treatment platelet reactivity in Asian patients with acute coronary syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(5):897–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plavix (clopidogrel bisulfate) [package insert] Bridgewater, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Sanofi-aventis. Sanofi-aventis; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilard M, Arnaud B, Cornily JC, Le Gal G, Lacut K, Le Calvez G, Mansourati J, Mottier D, Abgrall JF, Boschat J. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: the randomized, double-blind OCLA (Omeprazole CLopidogrel Aspirin) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(3):256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuisset T, Frere C, Quilici J, Morange PE, Nait-Saidi L, Carvajal J, Lehmann A, Lambert M, Bonnet JL, Alessi MC. Benefit of a 600-mg loading dose of clopidogrel on platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome undergoing coronary stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(7):1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patti G, Colonna G, Pasceri V, Pepe LL, Montinaro A, Di Sciascio G. Randomized trial of high loading dose of clopidogrel for reduction of periprocedural myocardial infarction in patients undergoing coronary intervention: results from the ARMYDA-2 (Antiplatelet therapy for Reduction of MYocardial Damage during Angioplasty) study. Circulation. 2005;111(16):2099–2106. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161383.06692.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta SR, Tanguay JF, Eikelboom JW, Jolly SS, Joyner CD, Granger CB, Faxon DP, Rupprecht HJ, Budaj A, Avezum A, Widimsky P, Steg PG, Bassand JP, Montalescot G, Macaya C, Di Pasquale G, Niemela K, Ajani AE, White HD, Chrolavicius S, Gao P, Fox KA, Yusuf S. Double-dose versus standard-dose clopidogrel and high-dose versus low-dose aspirin in individuals undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes (CURRENT-OASIS 7): a randomised factorial trial. Lancet. 2010 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huber K, Yasothan U, Hamad B, Kirkpatrick P. Prasugrel. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(6):449–450. doi: 10.1038/nrd2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandt JT, Close SL, Iturria SJ, Payne CD, Farid NA, Ernest CS, 2nd, Lachno DR, Salazar D, Winters KJ. Common polymorphisms of CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 affect the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic response to clopidogrel but not prasugrel. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(12):2429–2436. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo W, Gottlieb S, Neumann FJ, Ardissino D, De Servi S, Murphy SA, Riesmeyer J, Weerakkody G, Gibson CM, Antman EM. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(20):2001–2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montalescot G, Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Gibson CM, McCabe CH, Antman EM. Prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (TRITON-TIMI 38): double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):723–731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Effient (prasugrel) [package insert] Indianapolis, IN: Daiichi Sankyo, Inc. and Eli Lilly and Company; [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee Briefing Document: Effient (Prasugrel) Acute Coronary Syndromes Managed by Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Meeting Date: 03 February 2009. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/DOCKETS/ac/09/briefing/2009-4412b1-03-Lilly.pdf.

- 26.Mauri L, Kereiakes D. [Accessed 03/23/2010];The Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Study (DAPT Study) Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00977938.

- 27.TRITON TIMI 38. TIMI non CABG major bleeding in 30 day landmark analysis. Antman, EM Annual NY Symposium 2007; New York, NY. 2010. Data on file: www.lillymedical.com, [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coolong A, Mauri L. Clopidogrel treatment surrounding percutaneous coronary intervention: when should it be started and stopped? Curr Cardiol Rep. 2006;8(4):267–271. doi: 10.1007/s11886-006-0057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiviott SD, Trenk D, Frelinger AL, O'Donoghue M, Neumann FJ, Michelson AD, Angiolillo DJ, Hod H, Montalescot G, Miller DL, Jakubowski JA, Cairns R, Murphy SA, McCabe CH, Antman EM, Braunwald E. Prasugrel compared with high loading- and maintenance-dose clopidogrel in patients with planned percutaneous coronary intervention: the Prasugrel in Comparison to Clopidogrel for Inhibition of Platelet Activation and Aggregation-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 44 trial. Circulation. 2007;116(25):2923–2932. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.740324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jakubowski JA, Payne CD, Li YG, Brandt JT, Small DS, Farid NA, Salazar DE, Winters KJ. The use of the VerifyNow P2Y12 point-of-care device to monitor platelet function across a range of P2Y12 inhibition levels following prasugrel and clopidogrel administration. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99(2):409–415. doi: 10.1160/TH07-09-0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Payne CD, Li YG, Brandt JT, Jakubowski JA, Small DS, Farid NA, Salazar DE, Winters KJ. Switching directly to prasugrel from clopidogrel results in greater inhibition of platelet aggregation in aspirin-treated subjects. Platelets. 2008;19(4):275–281. doi: 10.1080/09537100801891640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li YG, Ni L, Brandt JT, Small DS, Payne CD, Ernest CS, 2nd, Rohatagi S, Farid NA, Jakubowski JA, Winters KJ. Inhibition of platelet aggregation with prasugrel and clopidogrel: an integrated analysis in 846 subjects. Platelets. 2009;20(5):316–327. doi: 10.1080/09537100903046317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montalescot G, Sideris G, Cohen R, Meuleman C, Bal dit Sollier C, Barthelemy O, Henry P, Lim P, Beygui F, Collet JP, Marshall D, Luo J, Petitjean H, Drouet L. Prasugrel compared with high-dose clopidogrel in acute coronary syndrome. The randomised, double-blind ACAPULCO study. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103(1):213–223. doi: 10.1160/TH09-07-0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]