Abstract

In spite of genome sequences of both human and N. gonorrhoeae in hand, vaccine for gonorrhea is yet not available. Due to availability of several host and pathogen genomes and numerous tools for in silico prediction of effective B-cell and T-cell epitopes; recent trend of vaccine designing has been shifted to peptide or epitope based vaccines that are more specific, safe, and easy to produce. In order to design and develop such a peptide vaccine against the pathogen, we adopted a novel computational approache based on sequence, structure, QSAR, and simulation methods along with fold level analysis to predict potential antigenic B-cell epitope derived T-cell epitopes from four vaccine targets of N. gonorrhoeae previously identified by us [Barh and Kumar (2009) In Silico Biology 9, 1-7]. Four epitopes, one from each protein, have been designed in such a way that each epitope is highly likely to bind maximum number of HLA molecules (comprising of both the MHC-I and II) and interacts with most frequent HLA alleles (A*0201, A*0204, B*2705, DRB1*0101, and DRB1*0401) in human population. Therefore our selected epitopes are highly potential to induce both the B-cell and T-cell mediated immune responses. Of course, these selected epitopes require further experimental validation.

Keywords: gonorrhea, vaccine designing, epitope mapping, antigenicity HLA alleles, immune response

Background

The disease, gonorrhea is a wide spread sexually transmitted disease caused by infection and transmission of N. gonorrhoeae. It is a drastic disease responsible for developing acquired immune deficiency syndrome(AIDS). Several attempts have been made for the development of vaccines for drastic diseases like AIDS [1] and flue viruses [2]. Vaccine development for gonorrhea, an age old disease is not in sight. However, several vaccine targets viz. protein-I B (porB) [3], opacity protein (opa), lipo-oligosaccharides, protein-I, lactoferrin-1 and -2 (lbpl, lbp2), Immunoglobulin A1 (IgA1) proteases [4], phospholipase A (pldA) [5], transferrin-binding protein -A and -B (tbpA and tbpB) [6–8], 2C7 oligosaccharide [9] have been identified for N. gonorrhoeae and few of them viz. pili (US4443431), T-cell stimulating protein-A and -B (tspA and tspB) (US6861507) have been patented. However, the problem still remains unsolved. Candidate vaccines identified and tested from these targets are only partially successful perhaps due to wide adoptability of the gonococcus, lack of proper animal models for the disease, cell lines to produce the vaccine, and inadequate immune response of used epitopes derived from these target proteins.

Secreted and surface proteins of any given pathogen are mostly antigenic and are responsible for pathogenicity [10]. Hence, these are good vaccine candidates. B-cell epitopes are parts of proteins that are antigenic and therefore are recognized by the antibodies. Identification of B-cell epitopes is useful development of diagnostic tests and can be employed as the first step in vaccine designing [11]. Similarly, effective immune response depends on specificity and diversity of the antigen binding to the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles [12] class I (recognizes CD8+ T-cells) and class II (recognizes CD4+ T-cells) [13,14]. The HLA molecules are highly polymorphic and according to IMGT/HLA Database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/imgt/hla/stats.html), there are 4,633 HLA alleles (Class-I =3,411 and Class-II = 1,222) [15]. Among these, DRB1*0101, DRB1*0301, DRB1*0401, DRB1*0701, DRB1*1801, DRB1*1101 and DRB1*1501 of Class-II HLA alleles are most frequent (20-50%) [16]. Evidences are that gonococcal infection decreases the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts [17,18] and Pili proteins modulate initial CD4+ T-cell proliferation and regulatory T-cell activation thereby may evoke immune responses [19]. Therefore both these T-cells mediated immunities should be considered in designing peptide vaccines against N. gonorrhoeae. A list of previously reported T-epitopes is given in Table 1).

Compared to the conventional vaccines, peptide or epitope based vaccines are easy to produce, more specific, and also safe. The advent of human genome project, sequencing and functional annotation of several pathogenic bacteria has boosted peptide based vaccine designing. Efficacy of computational prediction of effective B-cell and T-cell epitopes forms pathogenic genome as the key success to develop such vaccines. It is recommended to get an overview of various computational approaches in this regard [20].

Previously, we have reported several membrane associated essential proteins of the gonococcus using computational approaches that can be used in designing new vaccine (s) against the pathogen [21] In the present study, four such membrane associated essential gonococcal proteins are explored for designing peptide vaccine (s) using a novel in silico strategy combined with simulation and fold level verification to identify best possible and most effective epitopes that can produce both the B-cell and T-cell mediated immunity.

Methodology

Prediction of antigenic B-cell epitopes

Four essential membrane proteins namely D-alanineDalanine ligase (ddl), Sulfate transport permease protein C (cysW), Competence lipoprotein (comL), and Type IV pilin protein (pilV) of N. gonorrhoeae virulent strain FA 1090 earlier identified as best vaccine candidates [21] were selected for the current study and a novel approach of epitope designing was adopted where an epitope should produce both the B-cell and T-cell mediated immunity.

The complete amino acid sequence of each protein was retrieved from Swiss-Prot protein database (http://us.expasy.org/sprot) and analyzed using VaxiJen v2.0 antigen prediction server [22]. The default parameters (threshold=0.4, ACC out put) were used against bacterial species to check the antigenicity of each full length protein. Proteins having antigenic score >0.5 were selected. Each selected full length amino acid sequence was then subjected to transmembrane topology analysis using TMHMM v0.2 prediction server [23] in order to identify exo-membrane (surface exposed) amino acid sequences of each protein.

For prediction of B-cell epitopes, each full length protein sequence was subjected to BCPreds analysis [24] and all predicted B-cell epitopes (20 mers) having a BCPreds cutoff score >0.8 were selected. Selected B-cell epitopes were then subsequently checked for membrane topology by comparing with TMHMM results for exo-membrane amino acid sequences. Surface exposed B-cell epitope sequences having the cutoff value for BCPreds (>0.8) were selected and further analyzed using VaxiJen (threshold=0.4, ACC out put) to check the antigenicity. Finally 2-3 epitopes with top VaxiJen scores were selected for use in prediction of Tcell epitopes.

Prediction of T-cell epitopes from B-cell epitopes

T-cell epitopes were predicted from the selected B-cell epitopes. Both the sequence based and structure based QSAR simulation approaches were taken into account to predict T-cell epitopes and two screening steps were adopted. In the first screening, the selection criteria were:

the sequence should bind to both the MHC class-I and class-II molecules and minimum number of total interacting MHC molecules should be >15,

the sequence must interact with HLA-DRB1*0101 of MHC class-II, and

should be antigenic based on VaxiJen score.

Propred-1 (47 MHC Class-I alleles) [25] and Propred (51 MHC Class-II alleles) [26] servers that utilize amino acid position coefficients inferred from literature employing linear prediction model [27], were used to identify common epitopes that bind to both the MHC class molecules as well as to count total numbers of interacting MHC alleles. For QSAR simulation approach, the half maximal (50%) inhibitory concentration (IC50) and antigenicity of common epitopes predicted by Propred-1 and Propred was calculated using MHCPred v.2 [28] server (selecting DRB1*0101) and VaxiJen, respectively. Epitopes with highest antigenicity and those bind more than 15 MHC molecules comprising of both the MHC class I and II alleles and less than 100 nM IC50 scores for DRB1*0101 were selected. The second screening was structure based and QSAR simulation methods using T-Epitope Designer (http://www.bioinformation.net/ted/) [29] and MHCPred, respectively. Tepitope Designer predicts HLA-peptide binding based on virtual binding pockets using X-ray crystal structures of HLA-peptide complexes followed by calculation of peptide binding to binding pockets. The server can screen peptides for >1000 HLA alleles. In the second screening, the criteria were:

binding prediction with large number of HLA alleles (>1000),

the peptide should bind > 75% of total HLA molecules,

must bind with high scores to A*0201, A*0204, and B*2705, and

must bind to DRB1*0101 and DRB1*0401.

T-epitope Designer was used for criteria i), ii), and iii) and MHCPred was used for selection of DRB1*0101 and DRB1*0401 binding peptides. The final list of epitopes was made with non overlapping peptide sequences that pass these above mentioned criteria and VaxiJen and IC50 scores. Selected epitopes were further analyzed for fold level topology.

Epitope analysis

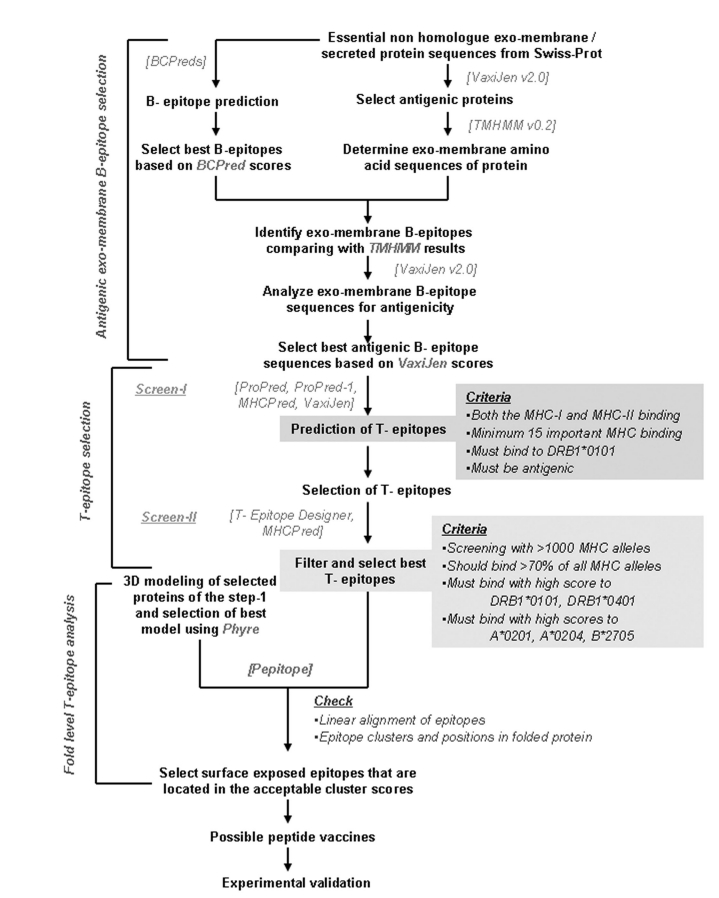

Homology modeling for each full length protein was carried out using Phyre version 2.0 web servers [30] and best models were selected based on super families and E-values of templates. The 3D folding and clusters of epitopes in folded protein were analyzed to confirm the exo-membrane topology of these epitopes using Pepitope server [31]. Pepitope was fed with Phyre derived 3D structures of each protein and all identified epitopes from the same protein to analyze the linear alignment of epitopes on the corresponding protein and to determine the epitope clusters and exomembrane position of epitopes in the folded proteins. The detailed method has been represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the overall epitope designing methodology employed in this study

Results

Antigenicity and topology of selected proteins

VaxiJen analysis of exo-membrane full length proteins selected for this study exhibited various degree of antigenicity ranging from 0.3986 to 0.6091 ( Table 2). Out of the four essential membrane proteins, cysW showed highest antigenicity (0.6091). Although comL exhibited the lowest score (0.3986) and predicted to be non-antigenic by VaxiJen, it was also considered for further analysis. The basic criterion of a good epitope is that it must be exposed to cell outside. The transmembrane topology analyses of these proteins were done using TMHMM and the result revealed that ddl (1- 304 amino acids) and comL (1- 267 amino acids) are fully exposed to outside of the membrane. The exo-membrane amino acid sequences of cysW are 42 ― 66 and 129 ― 137, and for pilV, the sequence is 30 - 129 (Table 2, column 6) ( supplementary material).

Antigenic B-cell epitopes

A peptide should be hydrophilic and produce both the B-cell and T-cell mediated immunity for becoming a good vaccine candidate [26]. Therefore to identify such epitopes, full length proteins were first subjected to B-cell epitope prediction using BCpreds and all B-cell epitopes were listed from each protein ( Table 3). Best epitopes were selected based on the criteria as mentioned in methods. In general, epitopes having BCpreds and VaxiJen cutoff values respectively >0.8 and >0.4 were selected except epitope from cysW where only one 20 mers epitope was found exposed to cell out side that has the BCpred and VaxiJen scores respectively 0.056 and 0.6316 ( Table 3). Therefore, two epitopes each from ddl, comL, and pilV and one from cysW were finally selected for further analysis ( Table 3).

B-cell epitopes derived T-cell epitopes

Each selected B-cell epitope was analyzed for identification of T-cell epitopes within the B-cell epitope sequence. For the first level screening, Propred-I (47 MHC Class-I alleles), Propred (51 MHC Class-II alleles), and MHCPred (DRB1*0101 allele) were used to identify common T-cell epitopes that share B-cell epitope sequence, can interact with both the MHC classes with highest number, and specifically interact with DRB1*0101 (as the DRB1*0101 is commonest bound allele, therefore the interaction epitope should produce better antigenic response) [32] (Table 4). At the second level of screening, identified peptides in the first screen were used to predict their binding abilities to >1000 MHC alleles using TEpitope Designer and epitopes that bind to >75% alleles were selected (Table 5). Similarly, as A*0201, A*0204, and B*2705 alleles are mostly used in various prediction methods [20], we set the cut off that selected peptides must bind to these three HLA molecules and T-epitope Designer was also used for this purpose ( Table 5). Since the frequency of DRB1*0101 and DRB1*0401 alleles of MHC class-II is 20-50% [16], we selected T-epitopes that interact with these two HLA molecules using MHCPred as described in methods ( Table 6). The final list of epitopes was made with non overlapping peptide sequences that confirm the above mentioned criteria and VaxiJen and IC50 scores ( Table 6). Finally, one epitope from each ddl, comL, cysW, and pilV are found to be prospective candidates for vaccine design ( Table 6). Selected epitopes were further analyzed for fold level topology.

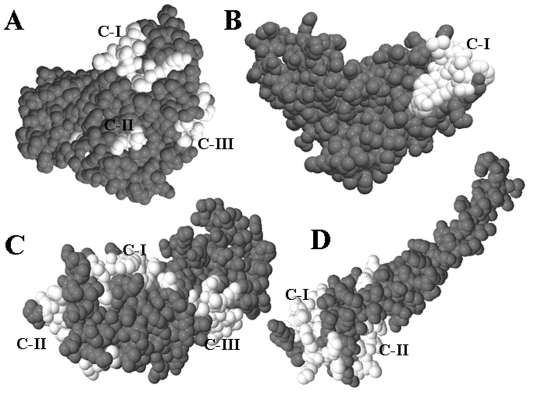

Clusters and folding of epitopes

There is every possibility of the identified epitopes getting folded inside the tertiary structure of the corresponding protein. Therefore, a fold level analysis of all identified epitopes was carried out to determine the position of epitopes in folded proteins and to confirm their exo-membrane topology. Homology based 3D structures of all four proteins were carried out using Phyre server as described under Methods. The Table 7 ( Table 7) represents the summary of Phyre results. Analysis of the epitope clusters and positions of epitopes with in the folded protein by Pepitope showed that identified all epitopes are situated within clusters having acceptable scores, located at the surface of the corresponding protein, and exposed to cell out side ( Table 4, bold highlighted in last column, and Figure 2 ). Therefore, these results confirmed the suitability of all identified epitopes as prospective vaccine candidates.

Figure 2.

Fold level characterization of cluster and topoloty of best epitopes using Pepitope (in white). Cluster numbers are also represented. A) ddl, B) cysW, C) ComL, and D) pilV.

Discussion

Bioinformatics approaches have been successfully used for identification of vaccine candidates in several pathogenic bacteria viz. Bacillus anthracis [33], Helicobacter pylori [34] and computer assisted epitope designing and peptide vaccine have been reported for many bacterial and viral pathogens including HIV [35], malaria [36]. In the present study, various bioinformatics tools have been used to identify and characterize potential epitopes from four vaccine targets of N. gonorrhoeae that might be effective to produce both the B-cell and T-cell mediated immunity. The identified epitopes are highly expected to bind both the class of MHC molecules specifically, A*0201, A*0204, B*2705, DRB1*0101, and DRB1*0401, that are most frequent MHC alleles in human population.

VaxiJen [22] that predicts antigenicity based on auto cross covariance (ACC) transformation of protein sequences into uniform vectors of principal amino acid properties with 82% accuracy, 91% sensitivity, and 72% specificity for bacterial species based on leave-one-out crossvalidation (LOO-CV) was used in this study to identify antigenicity of proteins and peptides. Strategically, B-cell epitope identification can be adopted as first step in vaccine designing [11] and BCpreds [24] that uses a novel method of subsequence kernel was used to predict linear B-cell epitopes from each protein. A good peptide vaccine must be exposed to cell out side and to predict the exo-membrane topology of amino acid sequences, TMHMM v0.2 prediction server [23] was used. In silico quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) [37] based T-cell epitopes have been reported recently. MHCPred [28] that uses additive method for binding affinity prediction of MHC molecules and the Transporter Associated with Processing (TAP) generates allele specific QSAR models using partial least squares (PLS) were used in the present study. MHCPred has been used to identify T-cell epitopes for malarial merozoite surface protein-1 [36] and a combination of SYFPEITHI, NetMHC. The MHCPred has been used for Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-2A [38]. Similarly, Propred and Propred-1 have been also used for the same purpose and these two server based T-cell epitope prediction have recently been reported for development of dengue virus vaccine [39]. To select MHC molecule binding peptides from a large number of MHC pool, we have also used T-Epitope Designer that predicts HLA-peptide binding calculated from structure based virtual binding pockets of HLA-peptide complexes [29]. We have also used two screening strategies to select T-epitopes in this study. The identified epitopes have been further characterized with Peptiope server [31] that predicts discontinuous epitopes based on a set of peptides that were affinityselected against a monoclonal antibody or peptides extracted from a phage display library. It also aligns a linear peptide sequence onto a 3D protein structure. Therefore, pepitope is helpful to identify epitopes based on physicochemical properties and spatial or fold level organization.

Considering the highest number of MHC allele binding epitope at the first level of T-epitope screening, “LNSSNYTRA” from comL cluster-I (Score: 18.045, Residue No: 10) is found to bind total 31 MHC alleles. Although it showed an antigenicity score of 0.8605, because of its high IC50 value for DRB1*0101 (216.77 nM), it may not be considered as a good vaccine candidate. Another epitope “LNKLASQDW” from comL Cluster-III (Score: 10.899, Residue. No: 10) that binds total 18 MHC molecules has antigenicity and IC50 scores 0.7699 and 36.39 nM, respectively. Therefore, this epitope is a better option than the previous one. The third epitope “DELNSSNYT” from comL cluster-I is found to bind total 11 MHC molecules but does not interact with any MHC-II alleles as per the Propred analysis. But the epitope has antigenic and IC50 (DRB1*0101) scores 1.0744 and 52.84 nM, respectively. Therefore, it is evident that epitope prediction differs according to different algorithms and the epitope “DELNSSNYT” may not be a good candidate for use as vaccine ( Table 4). Based on the second level screening, it has been found that epitope sequence “LNKLASQDW” can probably interact with all the HLA alleles (>1000) and specifically binds to our selected HLA molecules (A*0201, A*0204, B*2705, DRB1*0101, and DRB1*0401) with acceptable scores based on T-Epitope Designer, MHCPreds, and VaxiJen analysis ( Table 4, Table 5, and Table 6). Therefore this “LNKLASQDW” epitope is finally selected from comL.

Three epitopes from pilV are selected based on antigenic scores and IC50 values at screening-I. Epitopes “TCTVTLNDG” and “ETCTVTLND” of cluster-II (Score: 24.626, Residue. No: 13) showed antigenic scores 0.8669 and 1.1813, respectively. However, similar to the comL “DELNSSNYT” epitope, these two epitopes do not interact with any MHC-II alleles as per the Propred analysis but have IC50 values 5.66nM and 40.64nM, respectively for DRB1*0101 as analyzed with MHCpred. Therefore, these two epitopes may not be considered as vaccine candidates based on the same ground similar to comL. The third epitope “FEKYDSTKL” in cluster-I (Score: 43.692, Residue No: 17) is found to bind total 25 MHC molecules comprising of both the classes. The epitope has antigenicity and IC50 values 0.8655 and 8.73, respectively. Therefore, this epitope can be considered as best epitope among all epitopes derived form pilV ( Table 4). Results from the second level screening ( Table 5 and Table 6) also support its usefulness to be potential peptide vaccine.

Although the full-length protein is non-antigenic, one epitope “WDLYLKSLS” from cysW Cluster-I (Score: 46.051, Residue No: 13) is found antigenic (VaxiJen score: 1.3624) and can bind total 20 MHC molecules comprising of both the MHC classes. The IC50 value of this epitope for DRB1*0101 is 11.69 nM which indicates good inhibition of a given biological process by half (Table 4 see supplementary material). The epitope has also been found to bind selected MHC molecules (A*0201, A*0204, B*2705, and DRB1*0401) and more than 80% HLA molecules selected for second level T-epitope screening in this study ( Table 5 and Table 6). Therefore this epitope can be considered for vaccine development.

Among the identified epitopes from ddl, “YGEDGAVQG” of cluster-III having VaxiJen and IC50 scores 2.6304 and 20.18, respectively binds total 20 MHC alleles comprising of both the classes. This epitope is found to be best epitope having highest antigenicity among all epitopes identified from four proteins under study. Another epitope “YAFDPKETP” from ddl is also found suitable that has antigenicity and IC50 scores 0.6362 and 51.29 nM, respectively. This epitope is located in cluster-I (Score: 12.871, Residue No: 9) and interacts with 13 MHC class-I and 8 MHC class-II alleles ( Table 4). However, in the second screening, “YGEDGAVQG” peptide fails to bind A*0201, and A*0204 with positive scores (Table 6 see supplementary material) and is also capable to bind only 70% HLA molecules ( Table 5) based on T-Epitope Designer analysis. Therefore this epitope may not be suitable for designing a vaccine against the pathogen.

Conclusion

In this study, by using computational approaches based on sequence, structure, QSAR, simulation, and fold level analysis, we identified four potential T-epitopes derived from antigenic B-cell epitopes of four exomembrane essential proteins of N. gonorrhoeae. Selected T-epitopes [“LNKLASQDWȍ from coml., “FEKYDSTKL” from pilV, “WDLYLKSLS” from cysW, and “YAFDPKETP” from ddl] are antigenic and have much potential to interact with most common human HLA alleles (A*0201, A*0204, B*2705, DRB1*0101, and DRB1*0401). These epitopes are also found to interact with >75% of HLA molecules in a binding screening using T-Epitope Designer (that contains >1000 HLA molecules). Therefore these selected epitopes are likely to induce both the B-cell and T-cell mediated immune responses. Homology and simulation results also support the suitability of these epitopes as vaccine candidates. However, there are several pitfalls in developing a good vaccine and moreover there is lack of proper experimental disease model for gonorrhea; suitable animal model should be used for experimental validation of these epitopes to confirm these in silico results.

Financial disclosure

This work was carried out without any grant or financial support. There is no conflict of interest regarding this work.

Author contributions

DB: analyzed data and wrote the paper. ANM and AK provided inputs, reviewed analysis, and edited the article.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

We duly acknowledge the motivation and encouragement of all IIOAB members throughout the study.

Footnotes

Citation:Barh et al, Bioinformation 5(2): 77-85 (2010)

References

- 1.Ljungberg K, et al. Virolog. 2002;302:44. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark TW, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu W, et al. Vaccine. 2004;22:660. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbosa-Cesnik CT, et al. Genitourin Med. 1997;73:336. doi: 10.1136/sti.73.5.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bos MP, et al. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2222. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2222-2231.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price GA, et al. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3945. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.3945-3953.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas CE, et al. Infect Immun. 2006;74:1612. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1612-1620.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price GA, et al. Vaccine. 2007;25:7247. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gulati S, et al. Int Rev Immunol. 2001;20:229. doi: 10.3109/08830180109043036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerdino-tarraga AM, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:6516. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsen JE, et al. Immunome Res. 2006;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1745-7580-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuhns JJ, et al. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watts C. Immunol. 1997;15:821. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Germain RN. Cell. 1994;76:287. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson J, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D1013. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panigada M, et al. Infection and immunity. 2002;70:79. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.79-85.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anzala AO, et al. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:459. doi: 10.1086/315733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaul R, et al. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1525. doi: 10.1086/340214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plant LJ, et al. Infect Immun. 2006;74:442. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.442-448.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao B, et al. Int J Integrative Bi. 2007;2:127. Google Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barh D, Kumar A. In silico Bio. 2009;9:0019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doytchinova IA, Flower DR. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krogh A, et al. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.EL-Manzalawy Y, et al. J Mol Recogni. 2008;21:243. doi: 10.1002/jmr.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh H, Raghava GP. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1009. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh H, Raghava GP. Bioinformatics. 2001;12:1236. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sturniolo T, et al. Nat Biotechnology. 1999;17:555. doi: 10.1038/9858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guan P, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3621. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kangueane P, et al. Bioinformation. 2005;1:21. doi: 10.6026/97320630001001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:363. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayrose I, et al. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:3244. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eapen BR. Nature. 2009 hdl:10101/npre.2931.1. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ariel N, et al. Infect Imm. 2003;71:4563. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4563-4579.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dutta A, et al. In Silico Biol. 2006;6:43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Groot AS, et al. Vaccine. 2005;23:2136. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiwanitkit V. J Microbiol Immunol Infec. 2009;42:19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tian F, et al. Amino Acids. 2009;36:535. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang B, et al. Cell Mol Immunol. 2009;6:97. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Somvanshi P, Seth PK. Indian Journal of Biotechnology. 2009;8:193. Google Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kondo A, et al. Immunogenetics. 1997;45:249. doi: 10.1007/s002510050200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beaver JE, et al. Immunome Res. 2007;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1745-7580-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.