Abstract

Conceptions of adulthood have changed dramatically in recent decades, with shifts in the timing and sequencing of classic markers such as parenthood and school completion. Despite such changes, however, the notion that young people will eventually “settle down” and desist from delinquent behaviors is remarkably persistent. Uniting life course criminology with classic work on age norms and role behavior, we contend that people who persist in delinquency will be less likely to view themselves as adults, less likely to achieve behavioral markers of adulthood, and less likely to make timely adult transitions than others their age. Our analysis of longitudinal survey data and intensive interview data supports this proposition, with both arrest and self-reported crime blocking the passage to adult status. We conclude that settling down or desisting from delinquency is an important part of the package of role behaviors that define adulthood in the contemporary United States.

The transition from youth to adulthood represents a pivotal passage in the life course, typically marked by several meaningful transitions – entrance into the labor force, movement toward residential and economic independence, and independent family formation. Although movement away from delinquency also characterizes this transition (Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990; Sampson and Laub 1993), extant theory and research has yet to consider desistance as a marker of adult status. We here propose and test an interactionist model that emphasizes how delinquency and contact with the justice system shape the transition to adulthood.

Two related lines of research link the movement away from crime to traditional markers of adult status such as employment and marriage: (1) a well-established body of work specifying how these transitions affect the likelihood of crime or desistance (Horney, Osgood, and Marshall 1995; Laub, Nagin and Sampson 1998; Laub and Sampson 2003; Uggen 2000); and, (2) a burgeoning new literature tracing how crime and punishment, in turn, slow transitions to work (Hagan 1991; Pager 2003; Western 2006; Western and Beckett 1999) and family formation (Hagan and Dinovitzer 1999; Lopoo and Western 2005; Western, Lopoo, and McLanahan 2004).

Apart from its effects on other adult transitions, however, desistance from delinquency may itself constitute a dimension or facet of the transition to adulthood. The term juvenile delinquency generally refers to law violation committed by persons who have not yet reached the age of majority – typically age 18 or 19 in the contemporary United States. For most criminal offenses, the age-crime curve reaches its peak during the juvenile period (Hirschi and Gottfredson 1983). Although our interest extends beyond adolescence, we deliberately use the term delinquency throughout this paper to emphasize the historical and cultural link between criminality and youth – and the age-inappropriateness of delinquent behavior in adulthood.

Classic research on age norms (Neugarten, Moore, and Lowe 1965) has shown how widely-held beliefs about age-appropriate behaviors guide processes of adult socialization. Consistent with this research, we draw on work from the symbolic interactionist tradition (Mead 1934; Matsueda 1992; Maruna 2001; Giordano, Cernkovich, and Rudolph 2002) to argue that adults who persist in delinquency will recognize the age-inappropriateness of their behavior and internalize the appraisals of others, especially when delinquent behavior is made public through criminal justice system processing. The result of this recognition and internalization is a delayed passage to adult status, both objectively and subjectively.

Although U.S. correctional populations have risen to historically unprecedented levels (U.S. Department of Justice 2009), many people rarely encounter the criminal justice system. How can desistance constitute a facet of the transition to adulthood when some individuals have no criminal history from which to desist? First, a long line of self-report research establishes that almost all adolescents are involved in some form of delinquency (Elliott and Ageton 1980; Gabor 1994; Porterfield 1943; Short and Nye 1957; Wallerstein and Wyle 1947) and that rates of both official and self-reported delinquency decline precipitously during the late teens and twenties (Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990; Laub and Sampson 2003). According to the national Monitoring the Future survey, for example, most U.S. high school seniors have used illicit drugs (primarily marijuana) and participated in binge drinking (Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, and Schulenberg 2009). By age 30, however, the vast majority of these young people will have ceased or significantly reduced their illegal substance use and “settled down” into adult work and family roles (Bachman, O'Malley, Schulenberg, Johnston, Bryant, and Merline 2002).

Second, as with other markers of adulthood, such as marriage, childbearing, and financial self-sufficiency, desistance alone is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for attaining adulthood. It is not any single marker in isolation – for instance, many individuals have children but are not married – but rather a constellation of behaviors that constitutes adult status. We therefore place movement away from crime into the context of these more traditional indicators, examining the extent to which delinquency is embedded in and related to adult status. In doing so, we build upon classic and emerging work on the changing nature of adulthood (Arnett 2007; Buchman 1989; Furstenberg et al. 2004; Kennedy, McCloyd, Rumbaut, and Settersten 2004; Rindfuss, Swicegood, and Rosenfeld 1987) and criminal punishment as an increasingly common life event in the United States (Pettit and Western 2004).

Before testing these ideas, we first draw connections between the literatures on age norms, delinquency, and the behavioral and subjective dimensions of adult status. We conceptualize behavioral adult status in terms of the events or role behaviors long associated with adulthood, such as marriage and full-time employment (Goldscheider and Goldscheider 1999; Hogan and Astone 1986; Modell 1989). We conceptualize subjective adult status as self-perceptions regarding the extent to which persons feel like an adult (Furstenberg et al. 2004) and whether they feel “on-time” or “off-time” in making particular transitions (Hogan and Astone 1986). We then empirically assess six hypotheses about desistance and adulthood using two longitudinal surveys with repeated measures of behavioral and subjective adult status.

AGE NORMS, DELINQUENCY, AND ADULT TRANSITIONS

Age norms are shared prescriptions and proscriptions regulating the timing of life transitions, particularly the collective evaluations of when these transitions “should” or “ought” to occur (Marini 1984; Settersten and Mayer 1997). Neugarten et al. (1965) posited that expectations about adulthood and age-appropriateness are deeply embedded in U.S. culture, finding consistent evidence that behaviors deemed appropriate at one life course stage are deemed inappropriate at other stages. A pervasive network of informal social controls and accompanying sanctions thus govern the initiation, continuation, and cessation of social behavior, which is internalized as a “social clock” (Neugarten and Hagestad 1976:35) or “normative timetable” (Elder, Johnson, and Crosnoe 2003). This line of research extends beyond the prescriptive ages for traditional adult status markers, such as settling on a career, to include widely-shared age proscriptions regarding behaviors that range from returning home to live with one's parents (Settersten 1998) to wearing a bikini in public (Neugarten et al. 1965).

People who are “off-time” with respect to their social clock are unlikely to understand themselves as full-fledged adults. First, relative to others their age, they have yet to make socially expected transitions. This notion of lagging behind an important reference group is consistent with classic and contemporary interactionist work stressing social comparisons (Festinger 1954; Suls, Martin, and Wheeler 2002). Second, surveys consistently show that individuals recognize and internalize normative expectations about timely progression to adulthood (Furstenberg et al. 2004), measuring their progress relative to earlier points in their lives. This notion is consistent with interactionist work stressing temporal comparisons (e.g., Fry and Karney 2002). Building upon this interactionist tradition, temporal and social and reference comparisons should coalesce around a global assessment about whether one has achieved adult status (Johnson, Berg, and Sirotzki 2007; Shanahan, Porfelli, and Mortimer 2005).

Unquestionably, there is greater differentiation in the timing and sequencing of particular life markers today than in previous decades (Shanahan 2000). Nevertheless, contemporary research continues to find strong consensus about what it means to be an adult. In their analysis of General Social Survey data, Furstenberg and colleagues (2004) show that 90 percent of Americans believe it is important for adults to be financially independent, to complete their education, to work full time, and to support a family. Moreover, to be considered an adult, the vast majority of Americans think these markers should be attained by the age of thirty (Furstenburg et al. 2004). Similarly, Settersten and Hagestad (1996) report that over 75 percent of their U.S. sample perceive timetables or deadlines for attaining behavioral markers such as getting married and establishing an independent residence. Both classic and emerging research thus suggests that part of becoming an adult is engaging in age-appropriate behavior and attaining life course markers associated with adulthood in a timely fashion.

To date, this line of inquiry has yet to consider age-linked behaviors such as delinquency. If ideas about age-appropriateness extend to crime, a cultural expectation of desistance should parallel cultural expectations about family formation and other transitions. Although no studies to date, in particular among this age group, have asked how changes in delinquency affect respondents' perceptions of attaining adult status, there is some precedent for this idea in the psychological literature on the life course. In an influential series of articles, Jeffrey Arnett suggests that becoming an adult means “relinquishing certain behaviors that may be condoned for adolescents but viewed as incompatible with adult status” (1994:218), such as reckless driving. Using samples of students (1994) or respondents interviewed in public places (1997; 1998; 2003), Arnett finds that both young people and older adults (2001) regard avoiding illicit behaviors such as drunk driving, shoplifting, and vandalism as necessary criteria for a hypothetical person to attain adult status. Such findings do not appear to be limited to the U.S. context, as “norm compliance” is tied to conceptions of adulthood in nations such as Israel (Mayseless and Scharf 2003) and Argentina (Facio and Micocci 2003). Within the United States, this pattern appears to hold across racial and ethnic groups, as African Americans, Latinos, Whites, and Asian Americans all identify crime as incompatible with adult status (Arnett 2003).

Criminologists have long identified criminality with adolescence, and desistance with adult maturation (Glueck and Glueck 1945; Goring 1913). In fact, G. Stanley Hall, whose two-volume treatise Adolescence (1904) ushered in the scientific study of child development, was a strong advocate for the separate juvenile court system emerging in the early twentieth century (Rothman 1980:210). Since this time, age norms have been formally codified in distinctive juvenile and criminal codes. In keeping with these age-based behavioral standards, Moffitt (1993) and Greenberg (1977) have argued that some children and adolescents engage in delinquency precisely to mimic or attain the status accorded young adults. In the contemporary United States, for example, binge drinking is illegal and age-inappropriate for young adolescents, illegal yet age-appropriate for twenty year olds, and legal yet age-inappropriate for those over thirty (McMorris and Uggen 2000; Schulenberg and Maggs 2002). Because age norms govern delinquent behavior even in the presence of other roles, those who persist in delinquency are less likely to feel like adults or to be considered adults by others.1

To the extent that desistance is linked to other adult role transitions, the steep rise in punishment may even play some part in the extension of adolescence in the contemporary United States. Furstenberg and colleagues (2004) attribute the lengthening adolescent period to the increased time needed to obtain jobs that support families. Similarly, Arnett (2000) identifies a distinctive “emerging adulthood” life course stage for those 18 to 25 in societies requiring prolonged periods of education. While most emerging adults thrive on the freedom characterized by this period, Arnett (2007:71) notes that others “find themselves lost” and begin to experience mental health problems and other difficulties. Such problems are especially likely for vulnerable populations, including youth with a history of mental or physical health problems and those caught up in the justice system (Osgood et al. 2005; Arnett 2007).

Troubled transitions are especially common for those experiencing harsh punishment and its attendant effects on life chances and self-perceptions (Western 2006; Uggen, Manza, and Behrens 2004). For instance, by interrupting schooling and employment, incarceration may inhibit financial self-sufficiency and prolong dependency. The criminal justice system today cuts a wider and deeper swath through the life fortunes of young adults than it did a generation ago: more people are formally marked as criminals, and the long sentences they serve inhibit their educational and employment prospects (Pager 2003; Uggen and Wakefield 2005). Over 7.3 million Americans are currently under correctional supervision, up from 1.8 million as recently as 1980 (U.S. Department of Justice 2009).2 As longer sentences are meted out, young people remain in a dependent status for correspondingly longer periods. Not surprisingly, both prisoners and those self-reporting delinquency (Tanner, Davies, and O'Grady 1999) are “off-time” relative to their age cohort in traversing the behavioral markers of marriage, full-time work, school completion, and independent residency (Western and Pettit 2002; Uggen and Wakefield 2005).

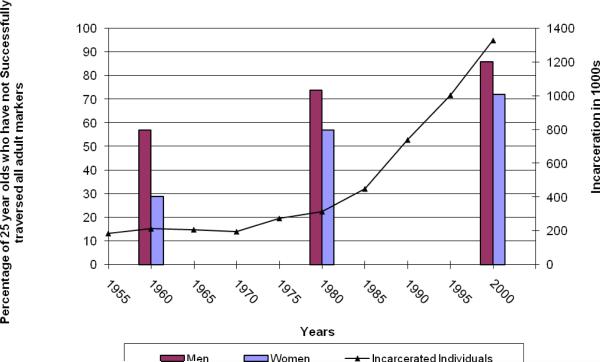

To illustrate the macro-level association between contact with the justice system and adulthood, Figure 1 plots incarceration rates against the percentage of young adults attaining status markers in the United States (the latter adapted from a similar analysis by Furstenberg et al. 2004). Incarceration increases clearly coincide with rising numbers of young people who have yet to traverse the markers of self-sufficiency, marriage, parenthood, and school completion. Over the last forty years, imprisonment has increased almost eight-fold. At the same time, the number of 25-year-olds attaining all markers has declined significantly -- a drop from 1960 levels of approximately 34 percent among men and almost 60 percent among women. Some portion of the latter decline is due to the rise of the single parent family, particularly among persons involved in the justice system, as well as more general trends in fertility and education attainment. Although young adults across the socioeconomic spectrum are attaining traditional adult markers later than in recent generations, it is also the case that entanglement in the justice system is delaying the adult transition for more Americans today than ever before.

Figure 1. The Behavioral Transition to Adulthood and Incarceration, 1955–2000.

Notes: Complete transitions include financial self-sufficiency, marriage, having a child, and completing education. Men are defined as self-sufficient if they have entered the labor force and have established independent residence. Women are defined as self-sufficient if they have entered the labor force or have established independent residence. Incarceration rates include state and federal prisons (U.S. Department of Justice 2004). Transition data taken from the U.S Census, IPUMS 1% sample in 1960, 1980, 2000.

Incarceration, of course, represents the most intense and invasive criminal sanction. By making public and dramatizing the consequences of age-inappropriate behavior, however, any form of justice system processing may affect self-perceptions of adult standing (Tannenbaum 1938; Lemert 1951). The detrimental consequences of crime and punishment for adult attainment are now well established. For instance, those with a history of delinquency have greater marital discord and lower socioeconomic attainment than those without delinquent histories (Laub and Sampson 2003; Pager 2003; Sampson and Laub 1993; Tanner et al. 1999; Western 2006). We here extend such research by elaborating and testing an interactionist model of delinquency and the transition to adult status, uniting research on conceptions of adulthood (Arnett 2001, 2007; Furstenberg et al. 2004) with work on the life course consequences of crime (Laub and Sampson 2003; Pettit and Western 2004) and desistance (Maruna 2001; Farrall 2002; Bottoms et al. 2004). Before presenting specific hypotheses, we outline our conceptual model of the mechanisms linking desistance to the subjective transition to adulthood.

AN INTERACTIONIST PERSPECTIVE ON DELINQUENCY AND ROLE TRANSITION

As noted, researchers have specified both behavioral and subjective dimensions of adulthood. Complementing work on behavioral markers, life course studies are now emerging on more subjective dimensions of adult status. This line of research considers individual perceptions of adulthood, or the extent to which people believe they are adults (Arnett 1994; 2003; Shanahan, Profeli, and Mortimer 2005; Eliason et al. 2007). For example, those who are married or self-sufficient are more likely to see themselves as adults than those who are unmarried or dependent (Johnson, Berg and Sirotzki 2007). To link such work to the sociology of crime and punishment, and to explain why “desisters” may feel more like adults than the “persisters,” a conceptual model linking age norms, role behaviors, and self-perceptions is needed.

A basic societal consensus about the role transitions, responsibilities, and capacities that signify adult status inform individuals' perceptions about whether they “measure up” as adults (Arnett 2001; Furstenberg et al. 2004). Alongside traditional markers such as parenthood and full-time employment, our conceptual model considers delinquency -- both serious and petty -- as central to shared understandings of adult status. We stress petty as well as serious delinquency because it is the age-inappropriateness of the conduct, rather than its severity, that guides feelings of adult status. In assessing whether and how they “measure up” as adults, people consider both temporal comparisons, in the form of individual assessments of behavior relative to that of earlier in the life course, and social comparisons, in the form of individual assessments of behavior relative to that of important reference groups. Symbolic interactionist theories have long recognized the importance of reference groups and the appraisals of others in shaping behavior and role identity (Blumer 1969; Felson 1985; Matsueda 1992). The emphasis on peer networks also has a long history in developmental criminology, stressing how peers replace the family as the central reference group during adolescence, before it shifts back to the family (or workplace) in adulthood (Giordano, Cernkovich, and Rudolph 2002; Giordano, Schroeder, and Cernkovich 2007; Haynie 2001; Laub and Sampson 2003; Warr 1998).

From an interactionist perspective, the appraisals of significant others play a large part in determining how people come to see themselves (Kinch 1963). Consistent with Cooley's (1922) notion of the looking-glass self (see also Matsueda 1992; Maruna et al. 2004), we suggest that those who persist in delinquency will be less likely to be seen as adults by their reference group (others' appraisals), more likely to perceive that others see them as less than adults (reflected appraisals), and thus more likely to understand themselves as less than adults (self-appraisals).

Structural symbolic interactionist theories provide a more general framework to explain the social psychology of subjective adulthood (Mead 1934; Stryker 1980; Stryker and Burke 2000; Wells and Stryker 1988). By this view, the self is organized into multiple identities corresponding to positions in the social structure. As people accumulate the responsibilities and perform the role behaviors commonly expected of adults, they begin to see themselves as adults in particular domains, such as the workplace or the family. The collective adherence to domain-specific roles supports the development of a generalized adult identity that is played out across different situations. Over time and with the accumulation of behavioral transitions and the accompanying role adaptation across different domains, the generalized adult role becomes more central to individual identity.

Empirical studies linking subjective perceptions of adulthood to adult role behavior generally support this account. Shanahan and colleagues (2005), for example, find that family transitions are key predictors of subjective adulthood and that some situations and settings are especially conducive to adult role behavior, such as spending time with colleagues in the workplace. These settings provide reference groups and foster behaviors that increase commitment to adult roles and encourage beliefs and attitudes culturally identified with maturity, thereby influencing perceptions of adult status. For example, accepting responsibility for oneself, achieving financial independence, and making decisions autonomously are associated with both adult role behavior and subjective perceptions of adult status (Arnett 1998; Greene, Wheatley, and Aldava 1992; Scheer, Unger, and Brown 1996).

Both delinquency and official sanctions, however, can disrupt adult role transitions-- and those subject to such sanctions are well aware of this fact. In their influential Dover Borstal study, Bottoms and McClintock (1973:381) found incarcerated young men to be prescient in forecasting the problems they would experience in traversing life course markers. Criminal punishment activates labeling processes that handicap offenders in marriage and labor markets (Matsueda 1992; Matsueda and Heimer 1997:178; Thornberry 1987; Pager 2003; Maruna, Lebel, Mitchell, and Naples 2004; Western 2006). Symbolic interactionist theories further suggest that “criminal role commitments” (Heimer and Matsueda 1994; Matsueda and Heimer 1997) encourage persistence in delinquent behavior, in part because the relevant reference groups tend to support criminal rather than conforming behavior (Giordano, Cernkovich, and Rudolph 2002).

The key point is that many forms of delinquency are widely recognized as age-inappropriate for adults, and thus the continuation of such behaviors is inconsistent with adult status. At first blush, the contribution of minor delinquency to our conceptual model may seem counterintuitive. Yet less serious forms of delinquency, such as petty theft or defacing buildings, may be particularly likely to suppress feelings of adult status. It is precisely because of their petty -- indeed childish -- nature that such peccadilloes diminish feelings of adulthood, even in the absence of a formal response by the justice system. In contrast, more serious criminal acts are likely to invoke criminal sanctions, which themselves have implications for adult status.

With regard to such sanctions, George Herbert Mead contrasted the “reconstructive attitude” of the then-emerging juvenile justice system (1918:597) with the hostile “retribution, repression, and exclusion” of the adult criminal courts (at 590). For Mead, as for Durkheim ([1893] 1984), only the adult criminal courts were capable of “uniting all members of the community in the emotional solidarity of aggression” (at 591). The common revulsion against criminality calls out the response of a generalized other – an organized attitude against crime – and thus affirms one's own status as an adult of good standing. By this view, society cannot treat older criminals with the same understanding and forgiveness accorded “wayward” children, since to do so would diminish social solidarity and shared conceptions of appropriate adult conduct. Indeed, even against the recent tide of “get tough” crime policies, the public supports the notion of a separate juvenile justice system and maintaining different standards for adult and youthful offenders (Mears, Hay, Gertz, and Mancini 2007). Such support for age-based disparate treatment signals widely held conceptions regarding the age-appropriateness of illicit acts.

Given the societal consensus on age-appropriate behavior and the expectations of settling down accompanying aging, persistence in delinquency undermines claims to adult status. A symbolic interactionist model suggests that conventional adult role behavior gradually fosters desistance by increasing commitments and thereby discouraging behaviors that may jeopardize the role. This view is largely consistent with the age-graded economic and social control mechanisms hypothesized by Laub and Sampson (2003). In addition, however, interactionists specify processes of role-taking and reflected appraisals (Matsueda 1992) and cognitive and emotional identity transformation (Giordano, Schroeder, and Cernkovich 2007) as the social psychological mechanisms linking age-graded role behavior and desistance. To the extent that those who persist in crime view themselves from the standpoint of a generalized other – the law-abiding adult citizenry – they will have great difficulty conceptualizing themselves as adults.

Following Lemert's classic distinction between primary and secondary deviance (1951), Maruna and Farrall (2004) have distinguished between primary and secondary desistance. Whereas primary desistance involves any lull or gap in offending, secondary desistance involves “the movement from the behaviour of non-offending to the assumption of the role or identity of a `changed person'” (Maruna, Immarigeon, and LeBel 2004:19). As Meisenhelder describes the interactive process of desistance, “individuals convince themselves that they have convinced others to view them as conventional members of the community” (1982: 138). By voluntarily forgoing delinquent opportunities, desisters also signal to potential spouses and employers that it is safe to build them into their future plans in an orderly and effective manner. The less delinquency and uncertainty in their lives, the more society can make use of young adults (Goffman 1967:174). In contrast, youth who have yet to desist from crime lack the stability and continuity desired for social organization. To be sure, many adults continue to seek excitement or “action” in disciplined or attenuated forms. Organized sports and legal gambling, for example, fall within a socially approved range of respectable adult leisure activities (Berger 1962). Nevertheless, the transition from “hell-raiser to family man” (or family woman) is one of identity change over the life cycle: adults are expected to settle down to fulfill the roles of spouse, parent, and provider (Hill 1974:190).

The failure to desist also triggers sanctions that increase in severity with age, further impeding the behavioral and subjective transition to adulthood. Such punishment may thus impact self-conceptions of adult status, independent of the effect of criminal persistence. In his classic study of prison life, Sykes observed how incarceration reduces prisoners to “the weak, helpless dependent status of childhood” (Sykes 1958:75). By making age-inappropriateness public, even less intensive sanctions such as arrest, jail stays, and probation impose a stigma that vitiates claims to adult status. As Erikson (1962) has noted, some societies consider deviance to be a natural mode of behavior for the young, with defined ceremonies to mark the transition from delinquent youth to law-abiding adult. In the contemporary United States, there are no such institutional means to remove the stigma of a criminal label and, hence, to clear passage to adult status (Becker 1963; Goffman 1963; Pager 2003). Those who persist in delinquency and those publicly identified as delinquent should therefore be least likely to think of themselves as adults.

HYPOTHESES

Based on prior research and an interactionist understanding of the adult transition, we develop six hypotheses to test our conceptual model. Our first hypothesis predicts the same general pattern of association noted by Sampson and Laub (1993; Laub and Sampson 2003), Maruna (2001), Giordano and colleagues (2002; 2007), and other criminologists: desistance is associated with transitions to full-time employment and marriage, as well as other adult markers, such as having children and achieving financial independence. To test this idea, we undertake a latent class analysis (McCutcheon 1987) of the transition to adulthood, assessing whether the data support a model that places desistance alongside other behavioral markers. This empirically locates patterns of desistance alongside more traditional markers of adult status without imposing any a priori structure as to the patterns of association on the data. The relative support for various model specifications will help show whether desistance is associated with or independent of other adult markers, just as the data reveal whether having a child is associated with or independent of marriage. Given the increasing individualization of the transition to adulthood, we expect at least three classes to emerge. In particular, we anticipate that having children may be associated with successful socioeconomic transitions for some and problematic transitions for others.

Hypothesis 1, Desistance and Other Behavioral Markers of Adulthood: Desistance from delinquency will be positively associated with other behavioral markers of adulthood, such that a latent class model that includes desistance, family formation, childbearing, school completion, and financial self-sufficiency will be supported by the data.

Hypothesis 2 examines a mechanism suggested by symbolic interactionist theory, linking social expectations about the age-appropriateness of role behavior to respondents' actual performance in such roles. We anticipate that performing roles associated with conforming activities, such as spending time with one's children, working, or voting, will evoke self-appraisals of one's adult status. In contrast, because of the widely held societal views of the age-inappropriateness of such behavior, engaging in delinquency will retard feelings of adult status.

Hypothesis 2, Delinquent Activities, Conforming Activities, and the Subjective Transition to Adulthood: Given the strong societal consensus around age-appropriate behavior and adult status, individuals will feel less like adults while engaged in delinquent activities and more like adults when engaged in conforming activities.

Entanglement in the justice system often disrupts the timely and orderly attainment of school, work, and family markers of adulthood. Hypothesis 3 extends the age norms literature (Neugarten et al. 1965) to propose that this disruption similarly extends to subjective perceptions about the timely attainment of behavioral markers of adulthood. This hypothesis addresses the relationship between justice system contact and domain-specific adult self-appraisals – measured as being “on time” or “off time” in the passage of various markers of adulthood. Those arrested will be more likely to report being “off time” with regard to socioeconomic transitions, family transitions, and other adult role behavior.

Hypothesis 3, Arrest and the Timing of Adult Markers in Specific Domains: Individuals who have been recently arrested will be less likely to appraise themselves as being “on time” in attaining the behavioral markers of adulthood than people who have not been recently arrested.

Arrest represents an application of formal social control, publicly labeling behavior as delinquent and, we suggest, age-inappropriate. According to labeling and symbolic interactionist conceptions of punitive justice, such sanctions mark individual rule-violators as outsiders, unfit to stand “shoulder-to-shoulder” with their fellow citizens (Becker 1963; Mead 1918). Given the importance of the appraisals of reference groups, the fourth hypothesis predicts that arrestees will be less likely to appraise themselves as adults.

Hypothesis 4, Arrest and the Subjective Transition: People who have recently been arrested will be less likely to report “feeling like an adult most of the time” than people who have not been recently arrested.

While desistance is generally conceptualized as an individual-level phenomenon, people also measure their behavior against that of the generalized other (Maruna 2001; Warr 1998). Of course, desistance may imply something quite different for those living in high-crime neighborhoods than for those living in low-crime neighborhoods or in an ideal-typical “society of saints” (Durkheim [1895] 1982). In addition to assessing desistance in terms of absolute levels or thresholds, we therefore also examine desistance relative to friends and others. This hypothesis is rooted in the symbolic interactionist emphasis on reference groups and the criminological emphasis on peers in the etiology of delinquency (e.g., Warr 1998). Given the importance of reference groups and social comparisons as a standard to measure behavior and to guide appraisals of adult status, Hypothesis 5 predicts that those who believe they are less delinquent than others in their reference group will be more likely to view themselves as adults.

Hypothesis 5, Relative Desistance and Reference Groups: People who believe they now commit less delinquency than others their age will feel more like adults than people who believe they are committing as much or more delinquency than others their age.

Our sixth hypothesis links people's judgments of their own desistance with their judgments about whether they are adults. This “subjective desistance” hypothesis is perhaps most central to the symbolic interactionist model, rooted in classic work on temporal comparisons, contemporary “narrative” theories of desistance (Maruna 2001) and widely-held views on age-appropriate behavior. Individuals who have moderated their delinquent behavior should be more likely to self-appraise themselves as adults than individuals whose delinquency has increased or remained stable. Even if perceptions about desistance are erroneous or inconsistent with measured behavior, our model predicts a strong tie between an internalized self-image as a desister and an internalized self-image as an adult.

Hypothesis 6, Subjective Desistance and Adult Status: People who report committing less delinquency than they did five years ago will feel more like adults than people who report committing as much or more delinquency than they did five years ago.

DESIGN STRATEGY: DATA AND MEASURES

Evaluating the Hypotheses

To evaluate Hypothesis 1, we will test a model of the transition to adulthood that includes desistance among more traditional behavioral markers of adult status. For this portion of the analysis we use latent class techniques (Clogg 1995; Lazarsfeld and Henry 1968; McCutcheon 1987) to ask whether the covariation between desistance and other transition markers is due to their mutual relationship to an unobserved or latent “behavioral adulthood” construct.

Our second and third hypotheses are premised on the idea that behaviors linked to roles such as parent and spouse intensify feelings of adult status, whereas behaviors linked to delinquent roles diminish feelings of adult status. To bring some evidence to bear on Hypothesis 2, we use self-reported survey data to compare whether respondents feel more or less like adults while they are engaged in various delinquent and conforming activities. To test Hypothesis 3, we compare the extent to which arrestees and non-arrestees feel “off-time” in attaining different work and family markers of adulthood. These self-appraisals provide a direct test of key predictions from interactionist theory.

Our final hypotheses specify the effects of three conceptualizations of delinquency and desistance upon subjective feelings of adult status. Hypothesis 4 considers arrest, Hypothesis 5 assesses “reference group desistance” based on a social comparison with friends, and Hypothesis 6 tests “subjective desistance” based on a temporal comparison with oneself five years ago. Here we estimate the effects of each delinquency and desistance measure on subjective adulthood before and after adjusting for the effects of transition markers such as work and marriage.

Even after statistically controlling for the effects of behavioral transition markers, however, it is possible that the observed effects of desistance on subjective adulthood are spurious due to a common or correlated cause. Some portion of the measured association between desistance and adulthood may thus be attributable to underlying differences across respondents in unmeasured factors, such as intelligence or ambition, that influence both one's decision to desist and one's self-conception as an adult. Moffitt's influential developmental taxonomy (1993), for example, might suggest stability in both delinquency and subjective adulthood among “life course persistent” offenders. We therefore introduce a lagged measure of perceived adult status in our final models. By statistically controlling for a prior sense of oneself as an adult, this model provides a variant of the static score or conditional change regression (Finkel 1995:6–11). The resulting estimates provide a more stringent test of desistance effects on subjective adulthood because they adjust for the influence of stable and unmeasured person-specific differences that may affect both desistance and self-appraisals of adult status. Such models also help address concerns about potential social desirability effects and other biases: because we use a lagged measure to capture change in adult perceptions, the effects of stable person-specific response biases should be minimized.

Data and Measures

Our primary data source is the Youth Development Study or YDS (Mortimer 2003), supplemented with the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (see appendix) and a small sample of interviews with convicted felons, collected as part of a project on criminal sanctions and civic participation.3 The YDS is a longitudinal survey of 1000 young people who attended Saint Paul, Minnesota public schools in the 1980s. Since 1988, when respondents were high school freshmen, they have reported information about their school, work, and family activities, civic participation, and delinquent involvement. In the 2002 wave of data collection, when most respondents were 29 to 30 years of age, we added a battery of questions developed to test the preceding hypotheses on desistance, self-appraisals, normative age expectations, and the transition to adulthood. Descriptive statistics for the variables to be analyzed are presented in Table 1. Approximately 75 percent of the sample is white and 43 percent are male. By 2002, 45 percent of respondents were married and 55 percent had children. The sample size for most analyses presented below is 708. The panel remains generally representative of the St. Paul cohort from which it was drawn, although attrition has been somewhat greater among racial minorities and less advantaged respondents (see Mortimer 2003:37–43 for details on panel attrition). More specifically, the sample remains substantively similar to that of the first wave of data collection across key indicators, including socioeconomic background, mental health, substance use, and achievement (Mortimer 2003:39).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | Description | Coding | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascribed Characteristics | ||||

| Male | Self-reported sex | 0=Female 1=Male | 43% | .49 |

| White | Self-reported race | 0=Other 1=White | 75% | .43 |

| Behavioral Adult Transitions (2002) | ||||

| Children | Presence of children | 0=No 1=Yes | 55% | .50 |

| Marriage | Marital status | 0=No 1=Yes | 45% | .50 |

| Educ. Attainment | Post-secondary degree (AA or higher) | 0=No 1=Yes | 39% | .48 |

| Self-sufficiency | Respondent and/or partner responsible for all of their living costs | 0=No 1=Yes | 72% | .45 |

| Voting | Participation in 2000 election | 0=No 1=Yes | 67% | .47 |

| Abstain | No crime (drunk driving, shoplifting, or simple assault) before 1998 or during 1999–2000. | 0=No 1=Yes | 20% | .40 |

| Desist | Crime prior to 1998 but not during 1999–2000. | 0=No 1=Yes | 43% | .49 |

| Persist | Crime both prior to 1998 and 1999–2000. | 0=No 1=Yes | 36% | .48 |

| Deviance (1999– 2002) | ||||

| Arrest | Arrested in 2000, 2001, or 2002 | 0=No 1=Yes | 6% | .22 |

| Reference group Desistance | Compared to others your age, do you do less, more, or about the same amount of partying, breaking work rules, or breaking other rules (such as drunk driving)? | 0=Same or more 1=Less | 60% | .49 |

| Subjective desistance | Compared to five years ago, do you do more, less, or about the same amount of partying, breaking work rules, or breaking other rules? | 0=Same or more 1=Less | 75% | .43 |

| Subjective Adulthood (1999,2002) | ||||

| Sub. Adult. 2002 | Do you feel like an adult most of the time? | 0=No 1=Yes | 71% | .45 |

| Sub. Adult. 1999 | Do you feel like an adult most of the time? | 0=No 1=Yes | 58% | .45 |

| Missing dummy | Missing 1999 subjective adulthood. | 0=No 1=Yes | 15% | .35 |

| Subjective Adult Transitions (2002) | ||||

| Do you feel early, on time, or late for each of the following events?” | 0=Off-time: very early or very late 1=Right on time or slightly early or late | |||

| Parent | Becoming a parent? | 0=Off; 1=On time | 64% | .48 |

| Married | Get married? | 0=Off; 1=On time | 68% | .47 |

| Financial indep. | Become financially independent? | 0=Off; 1=On time | 68% | .46 |

| Education | Complete school? | 0=Off; 1=On time | 69% | .46 |

| Full-time job | Get a full-time job? | 0=Off; 1=On time | 75% | .43 |

| Start a career | Start a career? | 0=Off; 1=On time | 74% | .44 |

| Subjective Adulthood by Domain (2002) | ||||

| “People feel more or less like an adult in different situations.… Please indicate if you feel like an adult in following situations?” | 0=Not at all or somewhat like an adult. 1=Entirely like an adult. | |||

| Voting | When I vote? | 0=No 1=Yes | 91% | .27 |

| Volunteering | When doing volunteer work? | 0=No 1=Yes | 75% | .43 |

| With children | When I am with my child/children? | 0=No 1=Yes | 69% | .46 |

| Limiting drinking | When I limit my drinking because I am driving or a “designated driver”? | 0=No 1=Yes | 86% | .34 |

| Working | When I am at work? | 0=No 1=Yes | 80% | .41 |

| Something wrong | When I do something I know is wrong? | 0=No 1=Yes | 36% | .48 |

| Violating law | When I do something against the law? | 0=No 1=Yes | 23% | .42 |

Our measures of behavioral markers of adulthood include marriage, educational attainment, employment status, and whether respondents have children, all taken in 2002. Given debates around the conceptualization and measurement of desistance (Massoglia 2006; Maruna and Farrall 2004; Bottoms et al. 2004), we assess delinquency and desistance four different ways -- behavioral self reports, official contact with the justice system, behavior relative to peers, and behavior relative to earlier in the life course. We then judge the collective weight of the evidence bearing on our hypotheses rather than basing conclusions on any single measure. To assess behavioral change in self-reported delinquency in our latent class analysis, we examine prior and contemporaneous information on drunken driving, theft, and violence. To test hypotheses 3 and 4, we use self-reported arrest data from 2000–2002, the time intervening between our subjective adulthood measures and self-appraisals. To examine hypotheses about relative and subjective desistance, we crafted items asking respondents to compare their behavior to that of others their age and to the levels they displayed five years ago. These measures were specifically designed to tap the hypothesized temporal and social comparisons with peers and reference groups.

To test Hypothesis 2 about delinquency and subjective adulthood, we use domain-specific questions regarding illicit and conforming behaviors. Respondents reported whether they feel more or less like an adult while hanging out with friends, caring for children, voting, and doing something against the law. Our outcomes for testing Hypothesis 3 are self-reported perceptions of the timeliness of reaching behavioral markers of adulthood. We test whether arrest decreases the likelihood that respondents feel “on-time” with respect to parenthood, marriage, financial independence, completing school, and obtaining a full-time job and career.

Finally, our key outcome for testing hypotheses 4, 5, and 6 is a global measure of subjective adult status, taken in 2002. This item is a self-appraisal of whether respondents “feels like an adult” most of the time, paralleling Arnett's “personal conception” indicator (1998) and other research on the subjective transition (Shanahan et al. 2005). To test how delinquent and conforming activities alter subjective perceptions, we exploit the longitudinal YDS design, incorporating a lagged subjective adulthood measure in our multivariate models. That is, we estimate the effect of delinquency and desistance from 1999 to 2001 on whether one feels like an adult in 2002, while statistically controlling for earlier subjective feelings of adulthood. For arrest, these models take the form:

| (1) |

where i represents individual respondents, Adult indicates the probability of feeling like an adult in 2002 and the lagged measure taken in 1999, Arrest represents an arrest occurring between 2000 and 2002, β signifies the effect of the independent variables, X denotes other explanatory variables, and α represents a constant term.4

In sum, the YDS is a rich longitudinal data set that tracks changes in delinquency and the behavioral and subjective transition to adulthood. Because the questionnaire items were tailored to our hypotheses, these data are well-suited for testing the proposition that desistance is a separate facet of the adult transition. We then conduct two supplementary analyses, based on a nationally representative survey (Add Health) and a smaller set of semi-structured interviews with persons in prison or under community supervision.

RESULTS

To assess our first hypothesis on behavioral markers, we use latent class analysis to model the behavioral transition to adulthood. This latent class analysis has two main functions. The first is to use patterns of covariation among the observed indicators to test whether the data support a model that includes desistance along with other behavioral markers of adult status. The second is to cluster individuals into classes or groups based on their transition patterns. Latent class techniques thus tell us whether the data are consistent with including desistance as a facet of the transition to adulthood, the number of distinctive patterns of transition behavior evident in the data, and the specific probabilities associated with traversing each of the markers in each class. For these models, we measure adult roles using indicator variables for having a child, marriage, a post-secondary degree, and financial self-sufficiency.

As noted, we consider multiple delinquency and desistance measures. For the latent class analysis, we sought a simple behavioral measure capturing common delinquency to parallel the marital, employment and other behavioral indicators in the model. This measure indicates the persistence (or, for a handful of cases, the initial onset) of delinquent involvement, desistance, and stable abstinence based on a combination of violent, property, and substance use.5 To be classified as a desister for this analysis, respondents must have participated in at least some of these activities prior to 1998 (when they were in their mid-twenties), but abstained from at least 1999 to 2000. We specified models with 1 to 5 latent classes, finding that the 3-class model shown in Table 2 best fits the data (Dayton 1998; McCutcheon 1987). All fit statistics support a specification that includes delinquency among other facets of the transition to adulthood, consistent with Hypothesis 1.

Table 2.

Behavioral Desistance and the Latent Structure of the Transition to Adulthood

| Conditional Probabilities: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Behavioral Transition | Response | Multifaceted | Socioeconomic | Problematic |

| Children | No | .281 | .989 | .267 |

| Yes | .719 | .010 | .733 | |

| Marriage | No | .101 | .884 | .876 |

| Yes | .898 | .116 | .123 | |

| Educational Attainment | No | .400 | .195 | .674 |

| Yes | .600 | .805 | .326 | |

| Self-sufficient | No | .099 | .257 | .351 |

| Yes | .901 | .742 | .649 | |

| Desistance | ||||

| Abstain | Yes | .204 | .184 | .199 |

| Desist | Yes | .532 | .478 | .264 |

| Persist | Yes | .264 | .337 | .537 |

| Latent class probabilities | .306 | .456 | .237 | |

Note: N=648 chi-square=37 df=27 index of dissimilarity=0.075

Note: Desistance is measured based on three offenses: Driving while intoxicated (“driven a car after having too much to drink” on multiple occasions), shoplifting (“taking something from a store without paying for it”), and simple assault (“hitting or threatening to hit”).

The model suggests that the behavioral transition to adulthood can be summarized by three patterns, which we identify as multifaceted, socioeconomic, and problematic transitions. Approximately 31 percent of the population from which the sample was drawn make up the multifaceted transition group. They are most likely to have desisted from our delinquency items (probability = .53), to be married (.90), and to have become self-sufficient (.90). They also report a high probability of having children and earning a post-secondary degree. In sum, they appear to have made a multifaceted or complete behavioral transition.

A larger group, comprising 46 percent of the population, appears to have made successful education and employment transitions while avoiding marriage and childbearing. We identify this pattern as indicating a socioeconomic transition. Members of this group are much more likely to desist (.48) than to persist in delinquency (.34), and they are more likely to have attained a post-secondary degree than those in the other latent classes. In contrast to the multifaceted group, few have married or had children. Nevertheless, their socioeconomic behavior and their desistance over the past three years clearly signal a successful transition to adult roles.

The final latent class, comprising approximately 24 percent of the population, may indicate a problematic transition. This group shows the lowest levels of degree completion (.33) and financial self-sufficiency (.65), the highest rates of persistence in delinquency (.54), and the lowest probability of desistance (.26). While they also report low rates of marriage (.12), they are approximately as likely as those making multifaceted transitions to be parents (.73). Aside from childbearing, members of this class have yet to transition into roles associated with adult status. In keeping with Hypothesis 1, they are unlikely to have desisted from delinquency.6

If models that include desistance among the other markers had provided a poor fit to the data, it would provide evidence against our first hypothesis that desistance is a facet of the transition to adulthood. This analysis, however, shows that conceptualizing desistance from common delinquency alongside other adult markers is consistent with these data while also identifying specific patterns of the transition to adulthood. Those who fail to move away from delinquency are far and away the least likely to have made other adult transitions. Moreover, because rates of abstention are similar across the three classes (.18 to .20), this pattern is unlikely to be accounted for by stable differences between abstainers who never participated in delinquency and others who had some history of delinquent behavior. Having modeled how desistance covaries with other behavioral markers, we now consider how delinquent and conforming activities influence perceptions of adult status.

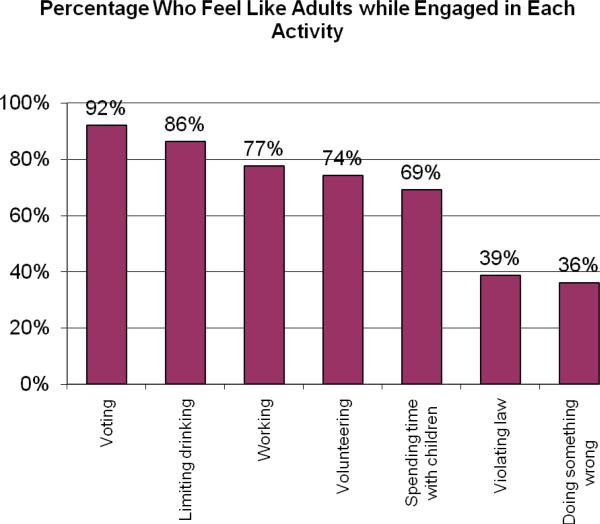

Figure 2 shows the relationship between participation in delinquency and feeling like an adult in different domains. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, behaviors associated with performing adult roles as parents, workers, volunteers, and law-abiding citizens – the latter measured by limiting drinking and serving as a designated driver – are much more strongly associated with adult status than are illegal or unethical behaviors. For example, a clear majority of respondents feel like adults when voting, working, and spending time with children but only 39 percent feel like adults when violating the law and 36 percent when doing things they know are wrong. This pattern supports the interactionist view that behaviors supporting roles such as parent and worker intensify feelings of adult status, whereas behaviors linked to roles such as law violator diminish such feelings. To the extent that the YDS sample represents a cross section of U.S. society, Figure 2 also helps establish the views of the generalized other and potential reference groups with regard to the age-appropriateness of delinquency and conformity.

Figure 2. Feelings of Adulthood when Engaged in Each Behavior.

Note: Percentages reflect those who report participation in each behavior (e.g., the time with children indicator reflects only those with children). The comparable percentages for the full sample are 81 percent for voting, 67 percent for limiting drinking, 72 percent for working 46 percent for volunteering, 39 percent for spending time with children, 31 percent for doing something wrong, and 23 percent for violating the law.

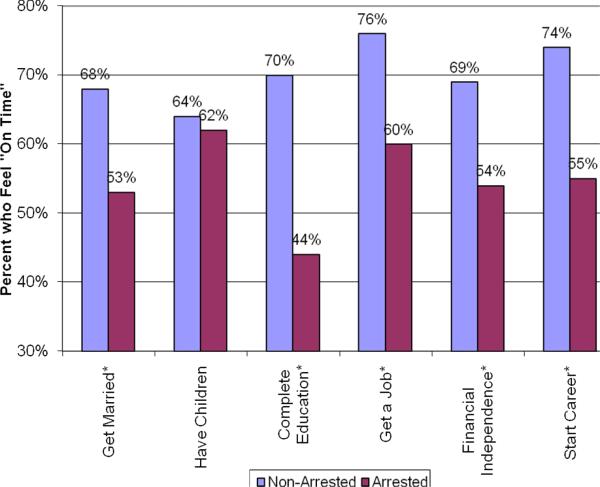

Hypothesis 3 returns to behavioral indicators of adult status and delinquency, in this case self-reported arrest. Figure 3 shows the percentage of respondents who believe they are “on-time” in attaining each behavioral marker, comparing those who had been arrested in the past three years with non-arrestees. As hypothesized, the recently arrested are significantly less likely to believe they are making timely progress in five of the six domains: marriage, schooling, employment, financial independence, and starting a career. Having children is the only marker in which we failed to detect a significant difference. Strikingly, only 44 percent of recent arrestees feel on-time with regard to completing their educations, relative to 70 percent of the non-arrestees.7

Figure 3. Percentage Reporting Feeling “On-Time” by Arrest Status.

Note: *p<.05 Respondents were asked to report whether they felt they were on-time for each behavioral marker. Response categories ranged from very early, to on time, to very late. Each outcome is coded 1 for on time and 0 for early or late in the attainment of these markers.

While the preceding analysis provides evidence linking delinquency to widely held conceptions of adulthood, it does not explicitly tap respondents' subjective sense of adult status. We next examine how delinquency is linked to a global self-appraisal of adult status. Each set of models incorporate demographic factors, behavioral markers, and lagged mirror measures of adult status taken prior to measures of delinquency and desistance. This lagged variable helps adjust for the effects of enduring differences across persons in stable characteristics such as impulsiveness or criminal propensity over the life course. We consider the effects of arrest in Table 3 and the effects of reference group desistance and subjective desistance in Table 4.

Table 3.

Arrest and Subjective Adult Status - Logistic Regression Estimates (Standard Errors in Parentheses)

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrest (1=arrest in 2000–2002) | −1.362*** (.337) | −1.528*** (.404) | |||

| Male | −.574*** (.169) | −.473** (.173) | −.420* (.194) | −.291 (.199) | |

| White | −.080 (.197) | .079 (.205) | .031 (.232) | .026 (.237) | |

| Marriage | .468** (.173) | .079 (.193) | .089 (.213) | .016 (.216) | |

| Educational Attainment | −.364* (.173) | −.156 (.183) | −.134 (.211) | −.209 (.215) | |

| Self sufficiency | .405* (.192) | .436* (.216) | .424* (.219) | ||

| Children | .866*** (.197) | .748*** (.219) | .867*** (.224) | ||

| Voting | .464* (.217) | .494** (.221) | |||

| Prior adult status (1999) | 2.222*** (.219) | 2.205*** (.221) | |||

| Missing dummy For prior adult status | .071 (.271) | .162 (.277) | |||

| Intercept | 999*** (.087) | .715** (.306) | −.296 (.326) | −1.075** (.400) | −.971* (.502) |

| N=708 | |||||

| −2 log likelihood | 831.94 | 825.93 | 802.82 | 677.14 | 662.47 |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.01

Table 4.

Reference Group Desistance, Subjective Desistance, and Subjective Adult Status - Logistic Regression Estimates (Standard Errors in Parentheses)

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Group Desistance | .472** (.168) | .245 (.200) | .096 (.215) | ||

| Subjective Desistance | .626*** (.183) | .557** (.221) | .518** (.235) | ||

| Arrest (1=arrest in 2000–2002) | −1.491*** (.406) | −1.552*** (.406) | −1.537*** (.408) | ||

| Male | −.304 (.199) | −.236 (.202) | −.238 (.202) | ||

| White | .035 (.237) | .015 (.238) | .023 (.239) | ||

| Marriage | −.013 (.219) | −.040 (.218) | .049 (.220) | ||

| Educational Attainment | −.187 (.215) | −.207 (.216) | −.201 (.216) | ||

| Self Sufficiency | .407* (.218) | .402* (.219) | .405* (.219) | ||

| Children | .860*** (.225) | .823*** (.225) | .817*** (.226) | ||

| Voting | .521** (.221) | .451* (.222) | .452* (.223) | ||

| Prior adult status (1999) | 2.171*** (.220) | 2.223*** (.224) | 2.226*** (.224) | ||

| Missing dummy for prior adult status | .157 (.278) | .091 (.281) | .084 (.280) | ||

| Intercept | .630*** (.125) | −1.082** (.415) | .457*** (.154) | −1.247*** (.426) | −1.268*** (.426) |

| N=708 | |||||

| −2 log likelihood | 841.72 | 663.78 | 837.04 | 656.12 | 655.47 |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.01

Note: Reference Group Desistance: Do you do less; a) partying, b) stealing from work c) other acts, (such as driving after having too much to drink) than friends your age?

Subjective Desistance: Do you do less; a) partying, b) stealing from work c) other acts, (such as driving after having too much to drink) than you did five years ago?

Estimates from logistic regressions of subjective adulthood on arrest are shown in Table 3. Model 1 reveals a strong bivariate association, with arrestees being about 74 percent less likely to report feeling like an adult (e−1.362 = .26).8 Model 2 shows the basic relationships between background indicators, behavioral markers such as marriage and employment, and subjective feelings of adult status. We find no evidence of significant race differences, but note sizable gender differences in subjective adulthood. On average, married respondents are more likely to feel like adults and those with higher levels of educational attainment are less likely to feel like adults.9 Model 3 folds in other adult markers, financial self-sufficiency and having children, using items mirroring those in the latent class analysis of the behavioral transition. Having children and attaining self-sufficiency, both positively associated with subjective adult status, reduce the effects of marriage and education to non-significance in model 3. Next, model 4 incorporates voting, an adult role behavior seldom considered in life course research, as well as the lagged measure of adult status. Both voting and, not surprisingly, prior subjective adult status are strong positive predictors of current subjective adulthood.10

Finally, model 5 of Table 3 incorporates each of the behavioral markers and a measure of arrest in the three years intervening between the subjective adulthood measures. Consistent with Hypothesis 4, arrest reduces the probability of feeling like an adult by approximately 78 percent (e−1.528 = .22). Including arrest in the model reduces the effect of gender to non-significance, suggesting that young men's greater likelihood of arrest partially explains why they are less likely to feel like adults than young women. With the exception of the lagged measure of adult status, the arrest coefficient is larger in size than any other predictor in the final model. The results in Table 3 thus provide strong evidence that arrest retards subjective adulthood, even net of behavioral transition markers, background factors, and prior feelings of adult status.

Having established a link between arrest and subjective adulthood, Table 4 considers the two conceptualizations of desistance suggested by our symbolic interactionist model and narrative accounts of the desistance process (Maruna 2001), as specified in Hypotheses 5 and 6. Reference group desistance refers to committing less delinquency than one's peers of the same age and subjective desistance refers to committing less delinquency than one had committed five years previously. Model 1 of Table 4 shows a significant correlation between reference group desistance and subjective adult status. Those who report committing less delinquency than others their age are about 60 percent more likely to report feeling like adults than those who report committing at least as much delinquency as their cohorts (e.472 = 1.60). In model 2, however, this relationship is rendered non-significant with the inclusion of a lagged indicator of adult status, voting, and other adult markers. As in Table 3, the negative effect of arrest remains statistically significant and large in magnitude.

In Table 4 model 3, we introduce our final delinquency indicator, subjective desistance. This measure taps whether respondents report committing less delinquency than they did five years ago. Model 3 shows that those who believe they are desisting are almost twice as likely to see themselves as adults as others (e.626 = 1.87). In contrast to reference group desistance, subjective desistance remains statistically significant when a lagged subjective indicator and the behavioral markers are included in the equation in model 4. Those who report subjective desistance are significantly more likely to feel like adults and those who are arrested are significantly less likely to feel like adults. As in the preceding models, financial independence, voting, and having children are all linked to subjective adulthood. Finally, model 5 of Table 4 includes all three delinquency measures. Although some precision may be lost due to collinearity across our multiple measures of delinquency and desistance, the results of this specification are again consistent with the preceding analyses. Arrest and subjective desistance predict subjective adulthood, with effects approximating or exceeding those of established markers such as marriage and employment.

To test the robustness of these findings on a nationally representative sample, we undertook supplementary analysis using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) in Appendix 1. In all cases, the analysis from Add Health supports the findings presented above. We emphasize the YDS analysis, however, because repeated subjective adulthood measures are needed for our lagged dependent variable approach to modeling individual change and because the subjective and reference group desistance items are only available in YDS. The Add Health analysis nevertheless helps confirm that the patterns observed in our Minnesota data may be generalized to a representative national sample. Appendix 1 shows that both serious and minor forms of delinquency are associated with decreased subjective adulthood in Add Health. Given the age structure of Add Health, we also tested for age effects in the relationship between offending and adult status. As the sample ages, delinquency becomes increasingly inconsistent with subjective feelings of adult status, in keeping with our interactionist model and the YDS results (not shown, available from authors).11

INTERVIEW DATA

While the relationships observed in our survey data are consistent with an interactionist account, these data cannot speak to all of the hypothesized mechanisms implied by this framework. To elaborate these results among those with more intensive involvement in the adult criminal justice system, we draw on the semi-structured interviews conducted with Minnesota felons described in note 3. Consistent with our conceptual model and the preceding analysis, interview participants clearly recognize the appraisals of others and the stigma associated with age-inappropriate delinquent behavior. Moreover, many linked movement away from crime to the process of becoming an adult, both behaviorally and subjectively. Their accounts are largely consistent with the interactionist model and our quantitative findings. For example, Michael, an African American probationer in his twenties, is acutely sensitive to the appraisals of others in recounting how a new robbery charge jeopardizes his standing as an adult in his neighborhood:

[I] caught a brand new case like three days ago, for narcotics. Now I've got to go to trial with that…For real. I'm about 25 now, and I need a decent family, decent job, car, going to work every day. I want to be there [in my neighborhood] so people would know, “hey, man, [Mike's] doing something, going to work every day, family going to church. He was out there wild, look at him now, he's changed.

For Michael, part of becoming an adult is “doing something” to attain the behavioral markers of adulthood, such as “going to work every day.” Also embedded in Michael's idea of adulthood, however, is moderating his “wild” earlier behavior, desisting from delinquency, and having a “decent” family (see, e.g., Anderson 1999). Michael's account is consistent with our survey results on moving away from delinquency – and forward with other aspects of life – during the passage to adulthood. Scott, another probationer in his mid-twenties, also pointed to his neighbors in distinguishing a “progression” toward adulthood from the simple passage of time:

You see the same alcoholic that you grew up with, or you seen drinking on the corner or you seen drinking around, or the same guy that used to be the best thief, that could steal anything, he's still doing it … the same girls, they've grown older, and they're doing the same things, you know? Then you got some people that … had the proper upbringing and the father and the- and you see them progress, or you hear about their progression, you know in the time that you were gone. This is just things that I noticed when I was locked up and this is the things that I seen. That's why I believe that things just don't change just because time goes by.

Scott's account echoes those of recent narrative models of desistance (Maruna 2001; Farrall 2002) and Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck's classic distinction between maturation and “chronological age” (1945:81). Returning from prison, he saw both desistance and persistence among the “guys and girls” in his neighborhood. Scott judges his adult passage against the behaviors and assessment of these peers -- what we have called reference group desistance -- and against earlier points in his own life -- what we have called subjective desistance. More generally, Scott's comments underscore the centrality of desistance in understanding the “progression” to adult status.

Other interview participants made more explicit temporal comparisons, referring to themselves as children or juveniles in recalling times of active offending. Thomas, a parolee in his twenties, noted he “was a kid back then,” but prison and “the fast life” became thoroughly incompatible with adopting desired adult family roles:

[Y]ou can't be a father when you're in jail… I never had a father, [he] was out doing God knows what. And I don't want my children to have to go through that, so knowing that, as you grow, the older you get, the wiser you become. The more right. You know what I'm saying? `Cause you can party `til your head fall off, but you know it ain't all about that. I wanted to live the fast life, but it ain't all about that anymore.

Such accounts are not limited to males. Pamela, a woman in her forties imprisoned on drug charges, similarly viewed fellow inmates as “kids” or children:

That's how the women are here, just beaten up. Beaten up little kids who grew up. They're like little kids walking around in woman bodies.

While Thomas and Pamela associated offending with childhood and adolescence, others elaborated on how the status of delinquent is inconsistent with other adult roles. Karen, a prisoner in her thirties, ticked off examples of successful adult role behavior, while noting that her passage was blocked by her felon status: “I am so much more than a felon, I am educated, I'm hard working, I'm a good mother, I am dependable, all of those things.” Dylan, who had served over a decade in prison for a crime committed while a teenager, lamented his slow progress toward assuming adult responsibilities:

I have so much to make up for, like lost time, and I have nothing to show for it. I'll get out when I'm 34. I have no house, no car, no anything.

Dylan clearly understood and internalized the widely-held cultural expectations surrounding a successful adult transition. He was thus keenly aware how his years in the justice system stunted his passage to adulthood, in both a material and a subjective sense.

Taken together, the interviews and the more systematic analysis of YDS survey data present a consistent picture of desistance and adult status. Across multiple indicators of desistance and contact with the justice system, movement away from delinquency emerges as an important part of the passage to adulthood. In the YDS analysis, the magnitude of the association between desistance and adult status is consistently exceeded only by having a child, marking desistance as one of the strongest predictors of subjective adulthood. These findings are similarly rendered in felons' accounts of their own passage. People measure their progress toward adult status against their earlier behavior and the expectations and behaviors of their reference groups. Those who do not move away from delinquency do not typically make a smooth adult transition, either subjectively or behaviorally. Such evidence supports conceptualizing desistance as a separate and important component of the multifaceted transition to adulthood.

TOWARD AN INTERACTIONIST THEORY OF DESISTANCE AND ADULTHOOD

Over four decades ago, classic life course studies identified strong societal consensus in the age norms governing social behavior (Neugarten et al. 1965). By this time, theory and research in the sociology of deviance had begun to link crime and punishment to conceptions of adulthood (Becker 1963; Erikson 1962; Sykes 1958). As correctional populations swell, scholars are increasingly blending these research traditions to consider crime and involvement with the justice system as a stratifying mechanism and an important life event (Laub and Sampson 2003; Western 2006). Our kernel notion here is that movement away from delinquency is a distinct dimension of the transition to adulthood. With the unique and perhaps expected exception of parenthood, those who fail to desist generally fail to attain the markers of adulthood in a timely fashion and are not accorded adult status by others. Internalizing these appraisals, they come to see themselves as less than adults. Clearly for some individuals and in some communities the correctional system impedes the timely transition to adulthood. People who have “done time” are significantly delayed in attaining markers of adulthood and some have suggested that the expansion of the penal state has reduced the number of “marriageable” male partners in some – predominantly African American – communities (Staples 1987; Wilson and Neckerman 1986; but see Lopoo and Western 2005).

Aside from involvement with the correctional system itself, however, a strong social expectation of desistance accompanies aging, such that cultural expectations about leaving crime parallel expectations about attaining markers such as marriage and self-sufficiency. People connect desistance with adulthood because they have internalized ideas about the age-appropriateness of delinquent conduct and its inconsistency with a sense of oneself as an adult. Continued involvement with the justice system and the failure to settle down or desist from delinquent behaviors further diminish these subjective feelings of adulthood.

We first tested a model of the adult transition that includes desistance from delinquency alongside work and family transition markers. Consistent with the predictions of developmental psychologists G. Stanley Hall (1904) and Jeffrey Arnett (2000), the latent class analysis reported in Table 2 shows how desistance is tightly bound up with other adult markers. We then asked whether people feel more like adults while engaged in conforming activities and less like adults while engaged in delinquent activities. Consistent with our interviews and symbolic interactionist theories of role behavior (Mead 1934; Wells and Stryker 1988), Figure 2 shows that pro-social acts such as voting evoke feelings of adulthood, while violating the law inhibits such feelings. Figure 3 offered support for our hypotheses about the importance of formal sanctions in the transition to adulthood (Becker 1963; Erikson 1962; Matsueda 1992; Maruna et al. 2004). Here, arrest diminishes perceptions that one is making timely progress toward adult markers across family, school, and work domains. We then considered the effects of delinquency and desistance on a global indicator of subjective adulthood. Consistent with labeling variants of symbolic interactionism, being arrested sharply diminishes the probability of feeling like an adult in our Tables 3 and 4. Moreover, as predicted by interactionist models of role transitions (Heimer and Matsueda 1994), subjective desistance increases the likelihood that individuals come to view themselves as adults.

The overall consistency and magnitude of the effects suggest that desistance from delinquency is a strongly predictive, and likely a constitutive, element of adulthood. In the final model of Table 4, those who subjectively desist are approximately 68 percent more likely to report feeling like adults than those who persist. Net of subjective desistance, formal justice system contact further bars passage to adulthood, as arrested individuals are about 79 percent less likely to report feeling like an adult than those who are not arrested. With the exception of having children and our lagged subjective adulthood indicator, these effects are stronger than all other variables in the model.

Settling down or transitioning from “hell raiser to family man” or woman (Hill 1974) is thus closely tied to both the behavioral transition to adulthood and the subjective sense that one has attained adult status. Considered in life course perspective, this study complements research suggesting that adolescents engage in delinquency specifically to attain adult status (Moffitt 1993; Greenberg 1977) or that associate minor deviance with precocious adult transitions among teenagers (Staff and Kreager 2008). When the current research is contrasted with studies on children and adolescents, it reveals an important irony regarding the relationship between delinquency and adult status: while delinquency may look like adult behavior to the teen or “tween,” we have shown that it consistently diminishes feelings of adult status for those in their late twenties and beyond.

The current study also helps refine research on identity shifts and desistance from crime (Giordano et al. 2002; Maruna 2001). Investigations based on interview data, case studies, and small-scale surveys are detailing a dynamic “secondary desistance” process, distinguishing simple gaps in offending from more fundamental identity transformations (Maruna, Immarigeon, and LeBel 2004:19; see also Giordano, Schroeder, and Cernkovich 2007:1613). The present analysis leverages longitudinal data from a representative community survey to explicitly model one such transformation – the development of an identity as a full-fledged adult. By examining repeated measures of subjective adulthood across multiple conceptions of delinquency and desistance, we find general support for the transformation processes described in other work.

It is perhaps noteworthy that the extension of adolescence has coincided with large-scale incarceration practices that increase the visibility and penetration of the justice system in everyday life. Our findings thus also accord with work on the extended adolescent period and recent documentation of a more halting and individualized progression toward adulthood in modern America (Furstenberg et al. 2004; Shanahan 2000), as well as research identifying incarceration as a common life event, particularly among less-educated African American men (Bonczar 2003; Dickson 1993; Pettit and Western 2004). Whereas prior work establishes the direct effect of punishment on adult status markers (Pager 2003; Staples 1987; Western 2006; Lopoo and Western 2005), however, we find that it also erodes individuals' sense of themselves as adults. We might speculate that erosion of adult status will, in turn, further delay progression into adult roles in the workplace, the family, and the community.

CONCLUSION