Abstract

Objective

To assess the effect of using stunting versus underweight as the indicator of child undernutrition for determining whether countries in Latin America and the Caribbean are on track to meet the component of Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 1 pertaining to the eradication of hunger, namely to reduce undernutrition by half between 1990 and 2015.

Methods

The prevalence of underweight and stunting among children less than 5 years of age was calculated for 13 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean by applying the WHO Child Growth Standards to nationally-representative, publicly available anthropometric data. The predicted trend (based on the trend in previous years) and the target trend (based on MDG 1) for stunting and underweight were estimated using linear regression.

Findings

The choice of indicator affects the conclusions regarding which countries are on track to reach MDG 1. All countries are on track when underweight is used to assess progress towards the target prevalence, but only 6 of them are on track when stunting is used instead. Another two countries come within 2 percentage points of the target prevalence of stunting.

Conclusion

Whether countries are determined to be on track to meet the nutritional component of MDG 1 or not depends on the choice of stunting versus underweight as the indicator. Unfortunately, underweight is the indicator officially used to monitor progress towards MDG 1. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the use of underweight for this purpose will fail to take account of the large remaining burden of stunting.

Résumé

Objectif

Évaluer l’effet de l’utilisation du retard de croissance comme indicateur de la dénutrition chez l’enfant au lieu du poids insuffisant afin de déterminer si les pays d’Amérique latine et des Caraïbes sont sur la bonne voie pour atteindre le composant de l’objectif 1 du Millénaire pour le développement (OMD) relatif à l’éradication de la faim, c’est-à-dire la diminution de moitié de la dénutrition entre 1990 et 2015.

Méthodes

La prévalence d’un poids insuffisant et d’un retard de croissance chez les enfants âgés de moins de 5 ans a été calculée pour 13 pays d’Amérique latine et des Caraïbes en appliquant les normes de croissance de l’enfant de l’OMS aux données anthropométriques accessibles au public et représentatives sur le plan national. La prévision de tendance (basée sur la tendance des années précédentes) et la tendance cible (basée sur l’OMD 1) du retard de croissance et du poids insuffisant ont été estimées à l’aide de la régression linéaire.

Résultats

Le choix de l’indicateur a des conséquences sur les conclusions concernant les pays qui sont sur la voie de l’OMD 1. Tous les pays sont sur la bonne voie lorsque le poids insuffisant est utilisé pour évaluer la progression vers la prévalence cible, mais seuls 6 d'entre eux le sont lorsque c’est l’indicateur du retard de croissance qui est utilisé. Deux autres pays présentent 2% de la prévalence cible du retard de croissance.

Conclusion

La détermination des pays à être sur la voie pour atteindre ou non le composant nutritionnel de l’OMD 1 dépend du choix du retard de croissance comme indicateur au lieu du poids insuffisant. Malheureusement, le poids insuffisant est l’indicateur qui est officiellement utilisé pour contrôler les avancées vers l’OMD 1. En Amérique latine et dans les Caraïbes, l’utilisation du poids insuffisant à cette fin ne parviendra pas à compter avec le fardeau restant du retard de croissance.

Resumen

Objetivo

Evaluar el efecto de la utilización del retraso del crecimiento o la delgadez como indicador de desnutrición infantil, para determinar si los países de América Latina y el Caribe están bien encaminados a cumplir la parte del Objetivo de Desarrollo del Milenio (ODM) 1, relativa a la erradicación del hambre, es decir, a reducir la desnutrición a la mitad entre 1990 y 2015.

Métodos

Se calculó la prevalencia de la delgadez y el retraso del crecimiento entre los niños menores de 5 años, en 13 países de América Latina y el Caribe, aplicando los Patrones de crecimiento infantil de la OMS a los datos antropométricos nacionales, representativos del país y disponibles al público. Para calcular la tendencia prevista (basada en la tendencia de años anteriores) y la tendencia objetivo (basada en el ODM 1) del retraso del crecimiento y la delgadez se empleó una regresión lineal.

Resultados

La elección del indicador influye en las conclusiones, por lo que respecta a qué países se encuentran en el camino correcto para alcanzar el ODM 1. Todos los países estaban encaminados cuando se empleó la delgadez como indicador para evaluar el progreso hacia la prevalencia del objetivo, mientras que sólo 6 de ellos se encontraron en el camino correcto cuando se empleó el retraso del crecimiento como indicador. Otros dos países se situaron a 2 puntos porcentuales de la prevalencia de referencia del retraso del crecimiento.

Conclusión

Los países se encontrarán o no en el buen camino para cumplir con el apartado relativo a la nutrición dentro del ODM 1 dependiendo de la elección del retraso del crecimiento o la delgadez como indicador. Desafortunadamente, el peso insuficiente es el indicador que se emplea oficialmente para controlar el progreso hacia el ODM 1. En América Latina y el Caribe, el uso de la delgadez con este objetivo no podrá tener en cuenta la gran carga restante del retraso del crecimiento.

ملخص

الهدف

تقييم أثر استخدام التقـزّم مقابل انخفاض الوزن كمؤشـر على قلة تغذية الأطفال من أجل تحديد سير أو عدم سير بلدان أمريكا اللاتينية وجزر الكاريبي على نهج بلوغ مكونات المرمى الأول من المرامي الإنمائية للألفية والذي يقضى بالقضاء على الجوع، وتحديداً تقليص معدلات قلة التغذية إلى النصف بين عامي 1990 و2015.

الطريقة

حُسِبَ معدل انتشار الوزن المنخفض والتقـزّم بين الأطفال دون عمر خمس سنوات في 13 بلداً من بلدان أمريكا اللاتينية وجزر الكاريبي من خلال تطبيق معايير منظمة الصحة العالمية لنمو الطفل على المعطيات الأنثروبومترية الممثلة للسكان والمتاحة للعامة.وباستخدام التحوف الخطي تم تقييم الاتجاه التنبؤي (الذي اعتمد على الاتجاه السائد في السنوات السابقة) مع الاتجاه المستهدف (وفقا للمرامي الإنمائية للألفية) في ما يختص بالتقـزّم وانخفاض الوزن.

الموجودات

يؤثر اختيار المؤشر على الاستنتاجات الخاصة بتحديد سير البلدان أو عدم سيرها في مسار بلوغ المرمى الأول من المرامي الإنمائية للألفية. وقد سلكت جميع البلدان هذا المسار عندما استخدم انخفاض الوزن كمؤشر في تقييم التقدم المحرز نحو معدل الانتشار المستهدف، لكن عند استخدام التقزم كمؤشر بدلا من انخفاض الوزن ظهر أن هناك ستة بلدان فقط هي التي تسلك هذا المسار. وهناك بلدان آخران قاربا على الوصول إلى 2% من نقاط معدل الانتشار المستهدف للتقـزّم.

الاستنتاج

إن تحديدسعيالبلدان لبلوغ المكون التغذوي للمرمى الأول من المرامي الإنمائية للألفية من عدمه يعتمد على اختيار مؤشر التقـزّم مقابل مؤشر انخفاض الوزن. ومن المؤسف، أن انخفاض الوزن هو المؤشر الرسمي المستخدم لرصد التقدم نحو بلوغ هذا المرمي. وفي بلدان أمريكا اللاتينية وجزر الكاريبي، فإن الاعتماد على استخدام انخفاض الوزن لهذا الغرض سيفشل في تقدير العبء المتبقي والمتمثل في التقـزّم.

Резюме

Цель

Оценить результат использования показателя задержки роста по сравнению с показателем недостаточного веса в качестве индикатора недостаточного питания у детей с тем, чтобы определить, движутся ли страны Латинской Америки и Карибского бассейна по пути достижения пищевого компонента Цели ООН №1 в области развития, сформулированной в Декларации тысячелетия (ЦРДТ), связанной с искоренением голода, а именно, по пути снижения вдвое доли населения, страдающего от недостаточного питания, в период с 1990 по 2015 год.

Методы

Распространенность недостаточного веса и задержки роста у детей в возрасте до 5 лет рассчитывалась для 13 стран Латинской Америки и Карибского бассейна путем применения Стандартных показателей ВОЗ в области развития ребенка к национально-репрезентативным общедоступным антропометрическим данным. Прогнозируемая тенденция (основанная на тренде за предыдущие годы) и целевая тенденция (основанная на ЦРДТ 1) применительно к задержке роста и недостаточному весу оценивались с использованием линейной регрессии.

Результаты

На выводы о том, движутся ли страны по пути к достижению ЦРДТ 1, влияет выбор индикатора. Если использовать индикатор недостаточного веса для оценки прогресса в отношении целевого показателя распространенности, то на правильном пути находятся все страны, но если использовать показатель задержки роста, то таких стран оказывается только шесть. В остальных двух странах наблюдается отставание от целевого показателя распространенности задержки в пределах двух процентов.

Выводы

Оценка того, находятся ли страны на пути к достижению ЦРДТ 1 в отношении питания, зависит от выбора недостаточного веса или задержки роста в качестве оценочного показателя. К сожалению, недостаточный вес является официально признанным индикатором прогресса на пути к достижению ЦРДТ 1. Использование для этой цели показателя недостаточного веса в странах Латинской Америки и Карибского бассейна не позволяет учесть сохраняющееся значительное бремя задержки роста.

摘要

目的

旨在评估使用发育不良和体重不足作为儿童营养不良的指标的效果,从而决定拉丁美洲和加勒比地区国家是否有望实现千年发展目标一(MDG1)中关于消除饥饿的部分,即在1990至2015年间减少一半的营养不良状况。

方法

通过将世界卫生组织儿童生长标准运用到可公开获得的具有全国代表性的人体测量数据上,计算出拉丁美洲和加勒比地区13个国家5周岁以下儿童中体重不足和发育不良的患病率。对于发育不良和体重不足是基于前几年数据预测的趋势和MDG1的目标趋势并使用线性回归进行的估计。

结果

指标的选择对国家有望达到MDG1结论有影响。当体重不足用来评估达到目标患病率的进程,所有国家均有望实现该目标。但是当发育不良用作该评估指标时,仅有6个国家有望实现所述目标。另有两个国家离目标发育不良患病率仍差2个百分点。

结论

要决定这些国家是否有望实现MDG1的营养部分取决于选择发育不良还是选择体重不足作为评估指标。遗憾的是,体重不足被正式用作评估指标,监测实现MDG1的进程。在拉丁美洲和加勒比地区,使用体重不足作为评估指标将不能正确解释大量的发育不良造成的疾病负担问题。

Introduction

Child growth is a gauge of individual and population-level well-being.1–3 Child height, in particular, reflects the cumulative effects of intergenerational poverty, poor maternal and early childhood nutrition and repeated childhood episodes of illness.4–6 It also reflects insufficient household purchasing power and poor access to education, housing, water and sanitation, and health services. Height not only tells the story of a nation with regard to maternal and child health and nutrition, but also of how equitably these have been distributed. This is particularly true in Latin America, which has some of the most pronounced inequity in the world.7

Maternal and child undernutrition contributed to more than one-third of all child deaths and to more than 10% of the total global disease burden in 2005.8 Of the nutritional factors leading to child death, stunting, severe wasting and intrauterine growth retardation together were responsible for 2.2 million deaths and 21% of disability-adjusted life-years. Therefore, improving nutrition in infants and young children is essential to achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) related to child survival (MDG 4) and the eradication of extreme poverty and hunger (MDG 1). Because of the intergenerational and far-reaching effects of early childhood nutrition on health and cognitive development,8–11 improving nutrition in infants and young children would indirectly contribute to progress towards achieving MDGs pertaining to universal primary education, gender equity, the empowerment of women and improved maternal health.

Growth in height and weight in accordance with the new child growth standards of the World Health Organization (WHO),12 which are internationally accepted, is used to evaluate the nutritional status of individual children and paediatric populations. Both weight gain and linear growth most directly reflect dietary intake and the effects of illness, as well as the interaction between these factors.5,6,13 However, linear growth is probably more indicative of nutrition in the intrauterine environment and of subsequent dietary quality. For population-level assessment, stunting is a better indicator than underweight because it reflects a cumulative growth deficit,14,15 which, unlike weight, cannot be reversed and is usually permanent when children remain in an environment marked by poverty.16

Because child height captures the effects of a broad range of economic and social influences on health, it is useful for monitoring progress towards several health and development objectives, including MDG 1. Unfortunately, underweight is the indicator of child undernutrition officially used to monitor progress towards achieving one of the targets linked to MDG 1, namely to reduce the prevalence of undernutrition by half between 1990 and 2015 throughout the world. This indicator has the disadvantage that it cannot distinguish between a drop in the prevalence of underweight resulting from improved linear growth or from increased weight-for-length/height. Increased weight-for-length/height across the population is not desirable because overweight in childhood predisposes to chronic non-communicable diseases in adulthood. The choice of indicator is decisive in determining whether countries are on track to meet the nutritional component of MDG 1 or not. In this paper we use both stunting and underweight as indicators to make this determination for countries in Latin America and the Caribbean and compare the results obtained with both indicators.

Methods

We applied the new WHO Child Growth Standards to anthropometric data provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, United States of America (USA), or downloaded, with permission, from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) web site (http://www.measuredhs.com/accesssurveys/start.cfm). All nationally-representative, publicly available data sets with anthropometric data for countries in Latin America and the Caribbean were included. Multiple data sets were available for 10 countries (the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua and Peru). Data from published reports, which used the new WHO Child Growth Standards, were extracted for the Plurinational State of Bolivia (2008),18 Brazil (2006),19 Costa Rica (1982, 1996, 2008),20 El Salvador (1966, 1988, 2008)20,21 the Dominican Republic (2007),17 Guatemala (1966)20, Honduras (1966, 1987),20 Mexico (1988, 1999, 2006),22 Nicaragua (1966, 1993, 2008)20,23 and Panama (1966, 1997, 2003).20 The preliminary report of the most recent national survey in Guatemala (2008) used the growth reference population of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) rather than WHO to report prevalence figures and thus could not be included in the present analysis. Only countries with nationally-representative surveys were included in the analysis. This limited the analysis to the subset of 13 countries with trend data represented in this study. The surveys are identified by country name, the year in which they were performed and sample size (Table 1). The most recent Peruvian survey, Peru 2004–2008, is ongoing and is being completed in several cycles. The anthropometric data used for all analyses for Peru, except for the subregional analyses, were collected in 2005. The data for the subregional analyses were collected in 2005, 2007 and the first round of 2008 (expanded survey). For the DHS data sets, starting in approximately 1999 (the fourth phase of surveys) all children less than 5 years of age in the household, and not just the children of the respondent woman, were measured for height and weight.

Table 1. Trends in the prevalence of underweight and stunting in 13 countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, by survey year (1966–2008).

| Country | Year | na | Prevalence |

Survey interval | Average yearly change in prevalence |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight |

Stunting |

Underweight |

Stunting |

||||

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | PP | PP | ||||

| Bolivia (Plurinational State of) | 1989 | 2 681 | 9.0 (7.7 to 10.4) | 42.1 (39.7 to 44.4) | – | – | – |

| 1994 | 3 008 | 12.6 (11.3 to 13.9)b | 34.6 (32.7 to 36.4)b | 1989–94 | 0.88 | −1.50 | |

| 1998 | 6 420 | 6.0 (5.4 to 6.7)b | 33.5 (32.2 to 34.8) | 1994–98 | −1.64 | −0.27 | |

| 2003 | 9 925 | 6.0 (5.4 to 6.7) | 32.6 (31.5 to 33.8) | 1998–03 | 0.00 | −0.17 | |

| 2008c | 8 422 | 4.1 (4.3 to 4.3)b | 26.8 (26.8 to 27.4)b | 2003–08 | −0.38 | −1.17 | |

| Overall | −0.26 | −0.80 | |||||

| Brazild | 1989 | 1 190 | 10.0 (8.2 to 11.7) | 19.9 (17.8–21.9) | – | – | – |

| 1996 | 4 364 | 4.7 (4.0 to 5.4)b | 13.5 (12.1–14.8)b | 1989–96 | −0.76 | −0.99 | |

| 2007 | 4 034 | 2.2 (NA) | 6.8 (5.4 to 8.3)b | 1996–06 | −0.23 | −0.57 | |

| Overall | −0.39 | −0.66 | |||||

| Colombia | 1986 | 1 335 | 8.7 (7.0 to 10.2) | 26.1 (23.7 to 28.6) | – | – | – |

| 1995 | 4 561 | 6.5 (5.7 to 7.2)b | 19.9 (18.7 to 21.1)b | 1986–95 | −0.24 | −0.69 | |

| 2000 | 4 239 | 5.0 (4.3 to 5.7)b | 18.3 (17.1 to 19.6)b | 1995–00 | −0.30 | −0.31 | |

| 2005 | 14 007 | 5.2 (4.7 to 5.6) | 16.3 (15.5 to 17.0)b | 2000–05 | 0.04 | −0.41 | |

| Overall | −0.18 | −0.52 | |||||

| Costa Rica | 1982e | 1 831 | 4.3 (NA) | 8.5 (NA) | – | – | – |

| 1996e | 662 | 2.1 (NA) | 7.6 (NA) | 1982–96 | −0.16 | −0.06 | |

| 2008–09 | 351 | 1.1 (NA) | 5.6 (NA) | 1996–08 | −0.08 | −0.17 | |

| Overall | −0.12 | −0.11 | |||||

| Dominican Republic | 1986 | 1 972 | 9.2 (7.8 to 10.6) | 22.3 (20.3 to 24.4) | – | – | – |

| 1991 | 3 284 | 8.5 (7.3 to 9.8) | 21.3 (19.5 to 23.2)b | 1986–91 | −0.14 | −0.20 | |

| 1996 | 3 841 | 4.8 (4.0 to 5.4)b | 13.7 (12.5 to 15.0)b | 1991–96 | −0.75 | −1.53 | |

| 2002 | 11 170 | 4.2 (3.8 to 4.8) | 11.8 (11.0 to 12.6) | 1996–02 | −0.08 | −0.32 | |

| 2007f | 10 522 | 3.1 (NA) | 9.8 (NA) | 2002–07 | −0.24 | −0.40 | |

| Overall | −0.29 | −0.60 | |||||

| El Salvador | 1966e | 635 | 22.4 (NA) | 56.7 (NA) | – | – | – |

| 1988e | 1 993 | 11.1 (NA) | 36.6 (NA) | 1966–88 | −0.51 | −0.91 | |

| 1993 | 3 518 | 7.0 (6.0 to 7.9) | 26.2 (24.6 to 27.8) | 1988–93 | −0.83 | −2.07 | |

| 1998 | 6 590 | 8.7 (7.8 to 9.5)b | 29.5 (28.1 to 30.9)b | 1993–98 | 0.34 | 0.65 | |

| 2003 | 5 294 | 5.5 (4.6 to 6.3)b | 20.8 (19.2 to 22.3)b | 1998–03 | −0.63 | −1.74 | |

| 2008b | 5 173 | 5.6 (NA) | 19.2 (NA) | 2008–03 | 0.02 | −0.31 | |

| Overall | −0.40 | −0.89 | |||||

| Guatemala | 1966e | 828 | 28.4 (NA) | 63.5 (NA) | – | – | – |

| 1987 | 2 250 | 27.9 (26.0 to 29.7) | 62.4 (60.4 to 64.4) | 1966–87 | −0.03 | −0.05 | |

| 1995 | 8 792 | 22.0 (20.9 to 23.0)b | 55.5 (54.1 to 56.9)b | 1987–95 | −0.73 | −0.86 | |

| 1999 | 4 055 | 20.5 (18.6 to 22.3) | 53.4 (51.0 to 55.8)b | 1995–99 | −0.38 | −0.53 | |

| 2002 | 6 505 | 18.0 (16.9 to 19.2) | 54.5 (52.8 to 56.2) | 1999–02 | −0.82 | 0.36 | |

| Overall | −0.29 | −0.25 | |||||

| Haiti | 1995 | 2 874 | 24.2 (22.6 to 25.8) | 37.5 (35.7 to 39.3) | – | – | – |

| 2000 | 6 502 | 14.1 (12.8 to 15.3)b | 28.9 (27.0 to 30.8)b | 1995–00 | −2.03 | −1.71 | |

| 2005 | 2 987 | 15.3 (17.4 to 20.9)g | 30.1 (28.1 to 32.2) | 2000–05 | 1.03 | 0.24 | |

| Overall | −0.50 | −0.74 | |||||

| Honduras | 1966e | 573 | 24.9 (NA) | 51.4 (NA) | – | – | – |

| 1987e | 6 147 | 14.8 (NA) | 42.7 (NA) | 1966–87 | −0.72 | −0.62 | |

| 2001 | 5 664 | 12.6 (11.6 to 13.5) | 34.6 (33.2 to 35.9) | 1987–01 | −0.16 | −0.58 | |

| 2005 | 10 320 | 8.7 (8.1 to 9.3)b | 30.1 (29.2 to 31.1)b | 2001–05 | −0.97 | −1.10 | |

| Overall | −0.41 | 0.54 | |||||

| Mexico | 1988h | 6 937 | 10.8 (NA) | 26.9 (NA) | – | – | – |

| 1999h | 7 590 | 5.6 (NA) | 21.5 (NA) | 1988–99 | −0.47 | −0.49 | |

| 2006h | 7 707 | 3.4 (15.4 to 15.7) | 15.5 (3.4 to 3.5) | 1999–06 | −0.31 | −0.86 | |

| Overall | −0.41 | −0.63 | |||||

| Nicaragua | 1966e | 573 | 24.9 (NA) | 51.4 (NA) | – | – | – |

| 1993 | 3 609 | 9.6 (NA) | 29.3 (NA) | 1966–93 | −0.57 | −0.82 | |

| 1998 | 7 200 | 10.4 (9.6 to 11.2) | 30.7 (29.5 to 31.9) | 1993–98 | 0.16 | −0.28 | |

| 2001 | 6 138 | 7.8 (7.1 to 8.6)b | 25.4 (24.1 to 26.6)b | 1998–01 | −0.86 | −1.78 | |

| 2006i | 6 535 | 5.5 (NA) | 21.7 (NA) | 2001–06 | −0.47 | −1.22 | |

| Overall | −0.49 | −0.74 | |||||

| Panama | 1966e | 600 | 9.6 (NA) | 29.4 (NA) | – | – | – |

| 1997e | 2 282 | 5.0 (NA) | 16.8 (NA) | 1966–97 | −0.15 | −0.41 | |

| 2003e | 2 893 | 5.3 (NA) | 23.7 (NA) | 1997–03 | 0.05 | 1.15 | |

| Overall | −0.12 | −0.15 | |||||

| Peru | 1992 | 7 874 | 8.9 (8.3 to 9.6) | 37.8 (36.6 to 38.9) | – | – | – |

| 1996 | 15 354 | 5.8 (5.4 to 6.2)b | 31.9 (30.1 to 32.8)b | 1992–96 | −0.78 | −1.47 | |

| 2000c | 11 884 | 5.2 (4.8 to 5.7) | 31.6 (30.6 to 32.6) | 1996–00 | −0.09 | −0.04 | |

| 2004–08j | 2 347 | 5.6 (4.5 to 6.7) | 29.8 (27.6 to 32.1) | 2000–05 | 0.08 | −0.36 | |

| Overall | −0.25 | −0.61 | |||||

CI, confidence interval; NA, not available; PP, percentage points.

Unless otherwise indicated data estimates are from analyses of DHS or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveys.

a Number of observations for weight-for-age calculations (represents maximum sample size) for children 0–60 months of age.

b Significantly lower than in previous survey (95% CIs do not overlap).

c Data from reference.18

d Data on underweight from the WHO Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition (http://www.who.int/nutgrowthdb/database/en/) [accessed 12 May 2009]. Data on stunting from reference.19

e Data from reference.20

f Data from reference.17

g Significantly higher than in previous survey (95% CIs do not overlap).

h Data from reference.22 Represents data for children 6–60 months of age.

i Data from reference.23

j For regional estimates only, data are from the 2005, 2007 and first-trimester amplified survey of 2008 (n = 9047 for weight and n = 8969 for height).

Analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Systems for Windows Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, USA) or STATA for Windows Version 11.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, USA). Individual z-scores for three anthropometric indices (weight-for-age, length/height-for-age, weight-for-length/height) in accordance with the WHO Standards12 were calculated using the SAS macro downloaded from the WHO web site (www.who.int/childgrowth/software). From the country survey data available we derived summary statistics to calculate the overall prevalence of underweight, stunting, wasting and overweight, along with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), as well as mean z-scores nationally and within particular subgroups (e.g. subregions, age categories). We defined underweight as a weight-for-age more than 2 standard deviations (SD) below the median; stunting as a length/height-for-age more than 2 SD below the median; wasting as a weight-for-length/height of more than 2 SD below the median, and overweight as a weight-for-length/height more than 2 SD above the median.

We used independent linear regression models and the prevalence figures for each country in Table 1 to study prevalence trends over time for stunting and underweight. Using regression coefficients, we estimated the prevalences for 1990 and 2015 and computed the yearly percent reduction in prevalence between 1990 and 2015. We then compared the estimated prevalences of stunting and underweight for 2015 with the target established for MDG 1(half of the estimated 1990 baseline prevalence). To evaluate progress we applied the classifications of “on track” and “insufficient,” used in the Countdown to 201524; countries were deemed to be “on track” if they were within 2 percentage points of the target prevalence.

Results

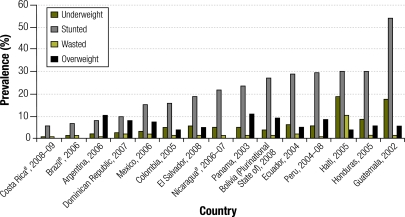

Stunting is the most common growth deficiency in Latin America and Haiti among children aged less than 5 years. Its prevalence in this group ranges from 5.6% in Costa Rica to 54.5% in Guatemala (Fig. 1). In contrast, the prevalence of underweight is less than 9% in all countries except Guatemala (18.0%) and Haiti (19.2%). In approximately half of the countries, the prevalence of wasting is lower than expected in a population with a normal distribution of weight-for-length/height. It is highest in Haiti (10.3%) and lowest in Honduras (1.4%), respectively. Overweight ranges from about 4% in Colombia and Haiti to 9% or more in Argentina, the Plurinational State of Bolivia, the Dominican Republic, Panama and Peru.

Fig. 1.

Estimated prevalence of underweight,a stunting,b wastingc and overweightd according to the WHO Child Growth Standards, most recent survey data for 15 countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, 2002–2008

a Weight-for-age 2 or more standard deviations below the median.

b Length/height-for-age 2 or more standard deviations below the median.

c Weight-for-length/height 2 or more standard deviations below the median.

d Weight-for-length/height 2 or more standard deviations above the median.

e Data for overweight are not available for Brazil, Costa Rica and Nicaragua.

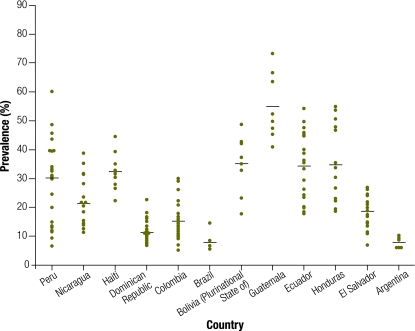

National prevalence estimates mask enormous within-country differences that are most pronounced in the case of stunting (Fig. 2). These within-country differences are sometimes larger than the differences observed between different countries in the region. Peru showed some of the largest within-country differences; the prevalence of stunting for the country as a whole was 29.8% but subregional estimates ranged from a low of 6.7% to a high of 60.1%. In general, within-country differences in the prevalence of underweight followed a similar pattern; regions with the highest prevalence of stunting also had the highest prevalence of underweight.

Fig. 2.

Within-country differences in the prevalencea of stunting, survey data for 12 countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, 1996–2006

a Each point represents the prevalence in each region; the country mean prevalence is represented by the horizontal line.

Although stunting has decreased gradually in all countries over the period covered by the surveys, different patterns emerge (Table 1). Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico and Nicaragua have experienced large declines in stunting between surveys. Brazil, with the largest decline, has seen a drop in stunting prevalence from 19.9% in 1989 to 6.8% in 2006. Costa Rica stands out for its very low prevalence figures throughout the measurement period. In the Plurinational State of Bolivia, stunting declined significantly between 1989 and 1994, remained stagnant between 1994 and 2003 and then declined again between 2003 and 2008. In Guatemala, stunting declined significantly between 1987 and 1995 and again between 1995 and 1999, but not between 1999 and 2002. Peru also had a large decline in stunting between 1992 and 1996, but not in the two subsequent surveys. El Salvador showed important declines until the last two surveys but none since. Haiti had a decline of almost 10 percentage points between 1995 and 2000 but stagnated between 2000 and 2005. Panama had a reduction of 13 percentage points between the first two surveys but had an increase of 7 percentage points between the last two. Overall, the average annual decline between the earliest and the most recent surveys (1966–2008) for all countries combined ranged from 0.89 percentage points in El Salvador to 0.25 percentage points or less in Costa Rica, Guatemala and Panama (Table 1).

Underweight declined following a pattern generally similar to that of stunting, with several exceptions (Table 1). In the Plurinational State of Bolivia, underweight declined significantly between 1994 and 1998, while stunting remained unchanged. Both Colombia and Guatemala experienced important declines in stunting between surveys, but not in underweight. Only Haiti displayed a significant increase in the observed prevalence of undernutrition; underweight showed a large increase during the last survey interval (2000–2005), while stunting did not change.

If underweight (the official MDG indicator) is used as the indicator to monitor undernutrition, all 13 countries analysed are on track to meet the target prevalence established for achievement of MDG 1 (Table 2). In contrast, if stunting is used as the indicator, only 6 of the 13 countries (Brazil, Colombia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Mexico and Nicaragua) are on track. Another two countries, Costa Rica and Haiti, are within 2 percentage points of the goal (Table 3) and are therefore considered on track as well. At the current predicted trends in stunting, the remaining 5 countries (the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama and Peru) are not on track to reach their goal, though the Plurinational State of Bolivia is within 3 percentage points of being on track.

Table 2. Estimated average yearly drop in underweight prevalence, estimated prevalence (1990 and 2015) and target prevalence for achieving Millennium Development Goal 1 in 13 countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, data for 1966–2008.

| Country | Drop in prevalence |

95% CI | Prevalence |

Progressb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated |

Target | |||||

| PP | 1990 | 2015a | ||||

| Bolivia (Plurinational state of) | −0.34 | −0.87 to 0.18 | 10.4 | 1.9 | 5.2 | On track |

| Brazil | −0.41 | −2.25 to 1.42 | 8.7 | 0.0c | 4.0 | On track |

| Colombia | −0.20 | −0.39 to −0.01 | 7.6 | 2.6 | 3.8 | On track |

| Costa Rica | −0.12 | −0.39 to 0.14 | 3.2 | 0.1 | 1.6 | On track |

| Dominican Republic | −0. 31 | −0.49 to −0.13 | 8.0 | 0.2 | 4.0 | On track |

| El Salvador | −0.42 | −0.58 to −0.25 | 11.1 | 0.8 | 5.6 | On track |

| Guatemala | −0.64 | −0.85 to −0.44 | 25.8 | 9.8 | 12.9 | On track |

| Haiti | −0.50 | −11.72 to 10.72 | 24.2 | 11.7 | 12.1 | On track |

| Honduras | −0.38 | −0.62 to −0.15 | 15.2 | 5.5 | 7.6 | On track |

| Mexico | −0.88 | −5.23 to 3.48 | 16.8 | 0.0c | 8.4 | On track |

| Nicaragua | −0.60 | −1.93 to 0.73 | 14.9 | 0.0c | 7.5 | On track |

| Panama | −0.13 | −0.47 to 0.22 | 6.5 | 3.3 | 3.3 | On track |

| Peru | −0.23 | −0.83 to 0.37 | 8.3 | 2.5 | 4.2 | On track |

CI, confidence interval; PP, percentage points.

a The predicted prevalence in 2015 was estimated by calculating the average annual change (in PP) per year between the first and last survey for each indicator in each country and applying the same rate of decline until 2015.

b Countries were deemed to be on track towards achieving MDG 1 if they were within 2 percentage points of the target prevalence.

c Estimated prevalences that had a predicted negative number in 2015 were set equal to 0.

Table 3. Estimated average yearly drop in stunting prevalence, estimated prevalence (1990 and 2015) and target prevalence for achieving Millennium Development Goal 1 in 13 countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, data for 1966–2008.

| Country | Drop in prevalence |

95% CI | Prevalence |

Progressb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated |

Target | |||||

| PP | 1990 | 2015a | ||||

| Bolivia (Plurinational State of) | −0.68 | −1.12 to −0.24 | 39.7 | 22.7 | 19.9 | Insufficient |

| Brazil | −0.72 | 2.14 to 0.70 | 18.6 | 0.6 | 9.3 | On track |

| Colombia | −0.51 | −0.79 to −0.24 | 23.5 | 10.6 | 11.8 | On track |

| Costa Rica | −0.11 | −0.48 to 0.26 | 7.8 | 5.1 | 3.9 | On track |

| Dominican Republic | −0.65 | −1.00 to −0.29 | 20.0 | 3.7 | 10.0 | On track |

| El Salvador | −0.89 | −1.17 to 0.61 | 34.1 | 11.9 | 17.1 | On track |

| Guatemala | −0.58 | −1.28 to 0.12 | 59.8 | 45.3 | 29.9 | Insufficient |

| Haiti | −0.74 | −7.92 to 6.45 | 39.5 | 21.2 | 19.8 | On track |

| Honduras | −0.53 | −0.77 to −0.28 | 39.6 | 26.4 | 19.8 | Insufficient |

| Mexico | −1.40 | −3.42 to 0.62 | 37.7 | 2.6 | 18.9 | On track |

| Nicaragua | −1.09 | −4.6 to 2.4 | 38.6 | 11.4 | 19.3 | On track |

| Panama | −0.24 | −2.93 to 2.46 | 23.0 | 17.1 | 11.5 | Insufficient |

| Peru | −0.55 | −1.41 to 0.31 | 37.3 | 23.6 | 18.7 | Insufficient |

CI, confidence interval; PP, percentage points.

a The predicted prevalence in 2015 was estimated by calculating the average annual change (in PP) per year between the first and last survey for each indicator in each country and applying the same rate of decline until 2015.

b Countries were deemed to be on track towards achieving MDG 1 if they were within 2 percentage points of the target prevalence.

Discussion

The choice of indicator for undernutrition clearly affects the conclusions about which countries are on track to reach the targets for reducing hunger related to MDG 1. Guatemala and Peru, the only two countries in the Americas among the 36 countries where 90% of the world’s stunted children live,8 illustrate the influence the choice of indicator can exert. Both countries are on track to achieve MDG 1 if underweight is used as the indicator, but not if stunting is used. If underweight is used as the indicator for undernutrition, countries will appear to be on track towards achieving the targeted prevalence established under MDG 1, but the large remaining burden of stunting will be ignored. In addition, as stunting is directly related to child mortality, actively monitoring its prevalence is also necessary to assess progress towards achieving MDG 4.

The relationship between stunting and underweight25 and between stunting and wasting shows regional differences26 that may affect the extent to which the analysis presented in our paper is applicable to other world regions. However, Latin America is not the only region in the world where stunting has a higher prevalence than underweight. An analysis of all recent surveys (2003–2004 to 2008) from 32 African and Asian countries using the Demographic and Health Survey STATComplier (accessed 4 March 2010) showed that all countries but four (Bangladesh, 2007; India 2005–06; Nepal, 2006 and Senegal, 2005), or 88%, had a prevalence of stunting that exceeded that of underweight. Therefore, the results of our study, which demonstrate the importance of the indicator used to determine whether countries are on track to meet the nutritional targets related to MDG 1, may be relevant to other world regions, although this requires empirical testing.

Our analyses have several limitations. Because no country had a survey in 1990, the baseline year for the MDGs, we used regression analysis to estimate the 1990 prevalence figures. Our predicted trends are also based on past trends and we cannot foresee whether the same rate of progress will continue until 2015, particularly since many of the governments of the countries included in the analysis have put reducing child stunting high on the political agenda with concomitant investment in resources. In addition, our analysis assumes that the progress between the first and last survey was linear, which was not always the case. Many countries experienced sharper declines during earlier surveys than in more recent years.

Regardless of which indicator is used for undernutrition, making it an objective to reduce the mean prevalence of undernutrition by half at the national level ignores the enormous within-country differences in the prevalence of undernutrition illustrated in Fig. 2 and will fail to identify regions whose lack of progress may be masked by the attainments of other regions. Thus, an additional objective under MDG 1 should be to set specific prevalence targets by subregion. The goal, for example, could be to reduce by half the prevalence of stunting in each subregion identified in the survey. This goal is particularly relevant in countries having the widest internal disparities in stunting.

Effective interventions to reduce stunting are available.27 Such interventions can also bring about improvements in human capital28 measured in terms of educational attainment, productivity and income and a reduced risk of developing chronic, non-communicable diseases.29 However, platforms for the delivery of these interventions, such as primary health- care networks, are weak,30,31 particularly in settings where stunting is a common problem. In the words of an expert, “we have the silver bullets to reduce child undernutrition but lack the rifles” (Victora CG, personal communication, 2010). Investment in improving delivery platforms and operations research to maximize the impact of this investment are urgently needed to maximize efficiency and deliver nutrition interventions known to be effective.

Efforts to address the underlying determinants of stunting can also bring about remarkable reductions in prevalence when accompanied by political leadership and investment, as shown by the recent decline of nearly 50% in Brazil (from 13.5% to 6.8% between 1996 and 2006).19,32 Two-thirds of this reduction is attributable to four factors: 25.7% to improved maternal schooling; 21.7% to an increase in the purchasing power of families; 11.6% to the expansion of health care; and 4.3% to improved sanitation. Importantly, the reductions were greatest in the poorest areas of Brazil, with a resultant decrease in disparities in stunting prevalence and in its detrimental consequences for individual and national development.33 Mexico has also achieved remarkable reductions through a concerted government effort targeting the poorest rural communities, where the demand for health and education services is created through conditional cash transfers.22,34 Although addressing the underlying determinants of stunting has been described as a long route to improving nutrition, the remarkable achievements by the governments of Brazil and Mexico over a relatively short period should trigger a re-evaluation of the timeframe required for strategies that address underlying determinants to achieve results. It should also make us reflect on how best to reduce stunting through an integrated strategy that implements the effective interventions identified in the recent Lancet series on maternal and child nutritional health27 while addressing the underlying determinants of undernutrition.

Countries throughout the world and the United Nations have made an important commitment to achieve the MDGs by 2015. Their actions should be guided by those policy frameworks, strategies and interventions that are most effective and the results should be evaluated vis-à-vis the indicator that best reflects the intended goal. As our results show, stunting rather than underweight should be included as a target for assessing progress towards achieving MDG 1, since, unlike underweight, it reflects the cumulative effects of undernutrition and predicts health and well-being in adulthood.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Garza C, de Onis M. Rationale for developing a new international growth reference. Food Nutr Bull. 2004;25(Suppl):S5–14. doi: 10.1177/15648265040251S102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Repositioning nutrition as central to development: a strategy for large-scale action Washington: The World Bank; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuklina EV, Ramakrishnan U, Stein AD, Barnhart HH, Martorell R. Early childhood growth and development in rural Guatemala. Early Hum Dev. 2006;82:425–33. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown KH. Diarrhea and malnutrition. J Nutr. 2003;133(Suppl):328S–32S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.1.328S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martorell R, Rivera JA, Lutter CK. Interaction of diet and disease in child growth. In: Atkinson SA, Hanson LA, Chandra RK, editors. Breastfeeding, nutrition, infection and infant growth in developed and emerging countries St John's: ARTS Biomedical Publishers and Distributors; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lutter CK, Mora JO, Habicht JP, Rasmussen KM, Robson DS, Sellers SG, et al. Nutritional supplementation: effects on child stunting because of diarrhea. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50:1–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/50.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Ferranti D, Perry G, Ferreira FHG, Walton M. Inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean: breaking with history. Washington: The World Bank; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, et al. Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371:243–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lozoff B, Georgieff MK. Iron deficiency and brain development. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006;13:158–65. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lozoff B, Jimenez E, Smith JB. Double burden of iron deficiency in infancy and low socioeconomic status: a longitudinal analysis of cognitive test scores to age 19 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:1108–13. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.11.1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramakrishnan U, Martorell R, Schroeder DG, Flores R. Role of intergenerational effects on linear growth. J Nutr. 1999;129(Suppl):544S–9S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.2.544S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO Child Growth Standards methods and development: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martorell R, Yarbrough C, Yarbrough S, Klein RE. The impact of ordinary illnesses on the dietary intakes of malnourished children. Am J Clin Nutr. 1980;33:345–50. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/33.2.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO Working Group Use and interpretation of anthropometric indicators of nutritional status. Bull World Health Organ. 1986;64:929–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lutter CK. Meeting the challenge to improve complementary feeding. In: United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition. SCN News. 2003;27:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martorell R, Khan LK, Schroeder DG. Reversibility of stunting: epidemiological findings in children from developing countries. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1994;48(Suppl 1):S45–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centro de Estudios Sociales y Demográficos. Encuesta Demográficia y de Salud, República Dominicana 2007 Calverton: Macro International Inc.; 2007. Spanish.

- 18.Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud 2008 La Paz: Ministerio de Salud y Deportes, Programa Reforma de Salud, Instituto Nacional de Estadística & Macro International Inc.; 2009. Spanish.

- 19.Monteiro CA, Benicio MH, Konno SC, Silva AC, Lima AL, Conde WL. Causes for the decline in child under-nutrition in Brazil, 1996–2007. Rev Saude Publica. 2009;43:35–43. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102009000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmieri Santisteban M, Mendéz Cabrera H, Delgado Valenzuela H, Flores Ayala R, Palma de Fulladolsa P. ¿Ha crecido Centroamérica? Análisis de la situación antropométrica-nutricional en niños menores de 5 años de edad en Centroamérica y República Dominicana para el período 1965-2006 San Salvador: Programa Regional de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutricional para Centroamérica; 2009. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demográfica E, de Salud F. 2008. San Salvador: Asociación Demográfica Salvadoreña; 2009. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rivera JA, Irizarry LM, González-de Cossío T. Overview of the nutritional status of the Mexican population in the last two decades. Salud Publica Mex. 2009;51(Suppl 4):S645–56. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342009001000020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Encuesta Nicaragüense de Demografía y Salud 2006–07. Atlanta: CDC; 2008. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bryce J, Harris J. Countdown to 2015: tracking progress in maternal, newborn and child survival New York: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sixth report on the world nutrition situation Geneva: United Nations Standing Committee on Nutrition; 2010.

- 26.Victora CG. The association between wasting and stunting: an international perspective. J Nutr. 1992;122:1105–10. doi: 10.1093/jn/122.5.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, Cousens S, Dewey KG, Giugliani ERJ, et al. Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet. 2008;371:417–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61693-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C, Hallal PC, Martorell R, Richter L, et al. Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet. 2008;371:340–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoddinott J, Maluccio JA, Behrman JR, Flores R, Martorell R. Effect of a nutrition intervention during early childhood on economic productivity in Guatemalan adults. Lancet. 2008;371:411–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shekar M. Delivery sciences in nutrition. Lancet. 2008;371:1751. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60757-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhutta ZA, Shekar M, Ahmed T. Mainstreaming interventions in the health sector to address maternal and child undernutrition. Matern Child Nutr. 2008;4(Suppl 1):1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lima ALL, Silva AC, Konno SC, Conde WL, Benicio MH, Monteiro CA. Causes of the accelerated decline in child undernutrition in Northeastern Brazil (1986–1996–2006). Rev Saude Publica. 2010;44:17–27. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102010000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monteiro CA, Benicio MH, Conde WL, Konno S, Lovadino AL, Barros AJ, et al. Narrowing socioeconomic inequality in child stunting: the Brazilian experience, 1974–2007. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:305–11. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.069195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rivera JA, Sotres-Alvarez D, Habicht JP, Shamah T, Villalpando S. Impact of the Mexican program for education, health, and nutrition (Progresa) on rates of growth and anemia in infants and young children: a randomized effectiveness study. JAMA. 2004;291:2563–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]