KT5823 modulates sodium/iodide symporter at multiple levels and will help uncover mechanisms underlying differential NIS regulation between thyroid and breast cancer cells.

Abstract

Na+/I− symporter (NIS)-mediated iodide uptake into thyroid follicular cells serves as the basis of radioiodine therapy for thyroid cancer. NIS protein is also expressed in the majority of breast tumors, raising potential for radionuclide therapy of breast cancer. KT5823, a staurosporine-related protein kinase inhibitor, has been shown to increase thyroid-stimulating hormone-induced NIS expression, and thus iodide uptake, in thyroid cells. In this study, we found that KT5823 does not increase but decreases iodide uptake within 0.5 h of treatment in trans-retinoic acid and hydrocortisone-treated MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Moreover, KT5823 accumulates hypoglycosylated NIS, and this effect is much more evident in breast cancer cells than thyroid cells. The hypoglycosylated NIS is core glycosylated, has not been processed through the Golgi apparatus, but is capable of trafficking to the cell surface. KT5823 impedes complex NIS glycosylation at a regulatory point similar to brefeldin A along the N-linked glycosylation pathway, rather than targeting a specific N-glycosylated site of NIS. KT5823-mediated effects on NIS activity and glycosylation are also observed in other breast cancer cells as well as human embryonic kidney cells expressing exogenous NIS. Taken together, KT5823 will serve as a valuable pharmacological reagent to uncover mechanisms underlying differential NIS regulation between thyroid and breast cancer cells at multiple levels.

The Na+/I− symporter (NIS) is a transmembrane glycoprotein that mediates iodide transport from the bloodstream into thyroid follicular cells for the biosynthesis of thyroid hormones. NIS also serves as the molecular basis of targeted radioiodine imaging and therapy of residual and metastatic thyroid cancer after thyroidectomy. Selective NIS expression and the retention of accumulated radioactive iodine by iodine organification in thyroid cells enhance the efficacy of radioiodide therapy of thyroid cancer and also minimize its adverse side effects in nontarget tissues (1).

Whereas NIS is not expressed in human nonlactating breast tissue, multiple studies have reported NIS expression in human breast cancers, suggesting a potential role of NIS-mediated 131I therapy (2–8). Unfortunately, only a minority of NIS-positive tumors have detectable radionuclide uptake in vivo (5–7). The predominant intracellular localization of NIS is believed to account for this because NIS must be at the cell surface to function in the process of active iodide uptake (2, 3). However, a recent paper indicated that NIS protein levels are generally low among breast cancers, and the observed intracellular staining is not specific to NIS (8). Strategies for selectively increasing cell surface NIS levels and/or radioactive iodide uptake (RAIU) activity in breast cancer are critical for realizing radionuclide therapy of breast cancer patients.

Along the same lines, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), which is the primary regulator of NIS expression in the thyroid, is elevated by T4 withdrawal or the administration of recombinant human TSH to selectively induce functional NIS expression in the thyroid gland for effective radioiodine therapy of thyroid cancer. In comparison, trans-retinoic acid (tRA) significantly induces functional NIS expression in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells (9), and glucocorticoids can further increase tRA-induced NIS expression in MCF-7 cells (10–13). Thus, tRA- and hydrocortisone-treated MCF-7 (MCF-7/tRA/H) cells serve as a convenient and effective model for studying NIS modulation in breast cancer. A better understanding of NIS regulation in breast cancer is necessary to devise strategies for selectively increasing cell surface NIS expression and function.

Many regulatory factors and cell signaling pathways have been shown to differentially modulate, sometimes even having opposite effects on, NIS expression and activity between thyroid and breast cancer cells. Interestingly, although TSH/forskolin/8-bromoadenosine-cAMP and other agonists of protein kinase A (PKA) signaling increase functional NIS expression in thyroid cells (14–18), they have no effect or slightly decrease NIS expression in MCF-7/tRA/H breast cancer cells (13). Similarly, although retinoic acid has been shown to increase functional NIS expression in MCF-7 cells (9) as well as in mouse mammary glands (12), it has previously been shown to decrease functional NIS expression in FRTL-5 nontransformed rat thyroid cells (13, 19). Kogai et al. (20) reported that pharmacological modulation of phosphoinositide-3 kinase signaling has opposite effects on NIS expression in FRTL-5 and MCF-7/tRA cells. Moreover, although inhibition of MAP/ERK kinase (MEK) signaling increases NIS mRNA (21) and protein levels (22) in RET/PTC-expressing PCCL3 rat thyroid cells, MEK inhibition leads to lysosomal-mediated NIS protein degradation in MCF-7/tRA/H cells (Zhang, Z., and S. Jhiang, unpublished data). Because KT5823, a staurosporine-related protein kinase inhibitor, was previously reported to further increase TSH-induced NIS mRNA expression and function in rat thyroid cells (23), we hypothesized that KT5823 may also regulate tRA/H-induced NIS expression in MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

In this study, we showed that KT5823 modulates NIS differentially between thyroid and breast cancer cells. We demonstrated that: 1) KT5823 further increases TSH-stimulated NIS expression in thyroid cells but has no effect on NIS expression in tRA/H MCF-7 cells; 2) KT5823 appears to modulate NIS activity at the posttranslational level in MCF-7/tRA/H cells but not in thyroid cells; and 3) KT5823 has a much more evident effect on the glycosylation status of de novo synthesized NIS in breast cancer cells than thyroid cells. Finally, the nature of hypoglycosylated NIS was characterized for the first time. The hypoglycosylated NIS is core glycosylated, has not been processed through the Golgi apparatus, but is capable of trafficking to the cell surface.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

PCCL3 rat thyroid cells were maintained in Coon's modified medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 5% calf serum, 2 mm glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 10 mm NaHCO3, and 6H hormone (1 mU/ml bovine TSH, 10 μg/ml bovine insulin, 10 nm hydrocortisone, 5 μg/ml transferrin, 10 ng/ml somatostatin, and 2 ng/ml l-glycyl-histidyl-lysine) unless otherwise specified. MCF-7 human breast cancer cells were maintained in a 1:1 ratio of DMEM and Ham's F-12 media (Life Technologies, Inc., Carlsbad, CA), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. MCF-7 cells were treated with tRA (1 μm)/H (1 μm) for 12 h for the induction of NIS expression, unless otherwise noted. Whereas MCF-7 cells were cultured in 5% charcoal-stripped FBS during treatments with tRA/H, they were cultured in 10% regular FBS after exogenous NIS transfection. SK-BR-3 and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies), 10% FBS, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells were cultured in DMEM (Life Technologies), 10% FBS, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. All cells were maintained in a 37 C incubator with 5% CO2.

Reagents

tRA, hydrocortisone, and KT5823, as well as the glycosylation inhibitors, tunicamycin, brefeldin A and monensin, and leupeptin and MG-132 were obtained from Sigma. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma) served as the vehicle control for the experiments involving KT5823.

Generation and transfection of full-length human NIS (FLhNIS) mutants

The FLhNIS cDNA clone (24) was used as a template for the generation of human NIS (hNIS) mutants by QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The introduction of mutations into the FLhNIS cDNA was confirmed by automated DNA sequencing (Plant-Microbe Genomics Facility, The Ohio State University). Wild-type (WT) and mutant hNIS cDNA were transfected into cells by electroporation (Amaxa nucleofector system; Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Radioactive iodide uptake assay

RAIU assay was performed as described by Knostman et al. (25). Briefly, 3 × 104 MCF-7 cells were seeded per well in triplicates. Then 2.0 μCi of I125 in 5 μm nonradioactive NaI was added to each well for 30 min at 37 C. Cells were washed with cold Hanks' balanced salt solution and incubated in cold 95% ethanol for 20 min to lyse cells and release intracellular I125. Cell lysate was counted in a γ-radiation counter and counts per minute were normalized to DNA amount using diphenylamine assay of trichloroacetic acid precipitates. RAIU activity not contributed by NIS-mediated iodide uptake was examined by conducting parallel experiments in the presence of perchlorate, a selective inhibitor for NIS-mediated iodide uptake.

Cell lysis and Western blot

Cells were lysed in buffer containing 50 mm Tris, pH 7.5; 150 mm NaCl; 5 mm EDTA; 1% Triton X-100; 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; 10 μg/ml aprotinin; and 10 μg/ml leupeptin. Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Western blot analysis was performed as described by Jhiang et al. (26) with the following modifications. Protein extracts of 100 μg in MCF-7/tRA/H cells and 50 μg in PCCL3 cells were subjected to 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. NIS protein in breast cancer cells was immunolabeled with the custom-generated rabbit anti-hNIS polyclonal antibody (26) (1:2000; Sigma Genosys, The Woodlands, TX), and rat NIS in PCCL3 thyroid cells was immunolabeled with PA716 rabbit antirat NIS (rNIS) polyclonal antibody (kindly provided by Dr. Bernard Rousset, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médical, Paris, France) (1:1500). Levels of phosphorylated vasodilator stimulated protein (VASP) (Ser 239) were detected with rabbit antiphosphorylated VASP (Ser 239) polyclonal antibodies (27) (1:500; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), and total VASP levels were immunolabeled with rabbit anti-VASP polyclonal antibodies (1:500; Cell Signaling Technology). Incubations with respective primary antibodies were followed by incubation with the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antirabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:4000; Invitrogen). Equivalent protein loading among samples was monitored by probing for β-actin with the mouse anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) followed by the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antimouse IgG secondary antibody (1:4000; Invitrogen).

Proteins were deglycosylated with peptide-N(4)-(N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminyl) asparagine amidase F (PNGase F), a glycosidase that eliminates all N-linked carbohydrates by cleaving carbohydrates adjacent to the asparagine residue. Briefly, 100 μg of protein was denatured with buffer (0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 0.04 m dithiothreitol) and incubated with 500 U of PNGase F (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). The deglycosylation reaction was enhanced by reducing buffer. Using procedures described for PNGase F, 100 μg of protein was also digested with endoglycosidase H (Endo H) (New England Biolabs), a glycosidase capable of cleaving high mannose oligosaccharides but not larger complex oligosaccharides.

Cell surface biotinylation

Cell surface biotinylation was performed as described by Vadysirisack et al. (22). Cells were washed with PBS supplemented with 0.1 mm CaCl2 and 1 mm MgCl2 and incubated with 1 mg/mL EZ-link Sulfo-NIHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for 45 min at 4 C. Cells were lysed after unreactive biotin was quenched with 20 mm glycine in PBS supplemented with 0.1 mm CaCl2 and 1 mm MgCl2 (Sigma). Approximately 1500 μg of total harvested protein was incubated with streptavidin-conjugated beads at 4 C overnight, beads were washed in lysis buffer, and cell surface proteins were eluted with SDS-PAGE loading buffer at 50 C for 5 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was loaded onto a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel for SDS-PAGE. Equivalent loading of cell surface proteins was monitored by probing for Na+/K+ ATPase with the mouse anti-Na+/K+ ATPase monoclonal antibody (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was performed as described in Marsee et al. (28) with the following modifications. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) and blocked with 1% BSA in permeabilizing buffer (0.1% saponin, 0.02% sodium azide, 0.1% BSA in PBS) overnight. After incubation with the affinity-purified p442 rabbit anti-hNIS polyclonal primary antibody (26) (1:500; Sigma Genosys) for 3 h, cells were washed with permeabilizing buffer followed by incubation with Cy3-conjugated donkey antirabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:1000; Invitrogen). Nuclei were stained with Hoescht 34580 (Invitrogen). Slides were mounted with Prolong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen). Cells immunolabeled with secondary antibody only served as a control for nonspecific fluorescence. NIS immunolabeling was detected and visualized with the Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope (Tokyo, Japan) at ×600 magnification using the Texas Red filter.

Statistical analysis

Simple two-group t tests were used to test for statistical significance. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

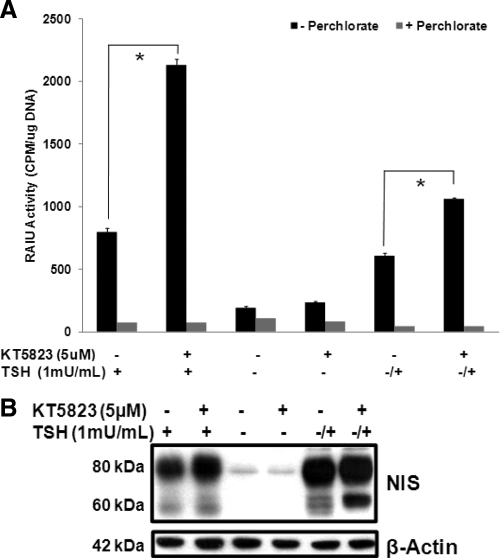

KT5823 further increases TSH-stimulated functional NIS expression in PCCL3 rat thyroid cells

In agreement with Fozzatti et al. (23), our results indicated that a 16-h treatment with 5 μm KT5823 increased RAIU activity (Fig. 1A) and NIS protein levels (Fig. 1B) by about 2-fold in PCCL3 rat thyroid cells chronically exposed to TSH. In PCCL3 cells deprived of TSH for 5 d and restimulated with TSH for 8 h to induce de novo NIS synthesis, KT5823 treatment increased RAIU activity by 74.4% and resulted in moderate increases in both 80 kDa mature glycosylated and 60 kDa hypoglycosylated NIS protein. However, a greater extent of increase in 60 kDa NIS compared with 80 kDa NIS suggests that KT5823 modestly inhibits glycosylation of de novo synthesized NIS protein. In the absence of TSH, KT5823 had no effect on NIS expression, suggesting that TSH was permissive for KT5823-mediated increases in the NIS expression. Taken together, although KT5823 alone was not sufficient to increase NIS expression in TSH-deprived PCCL3 thyroid cells, it further increased TSH-stimulated NIS expression, and thus radioiodide accumulation, in PCCL3 thyroid cells.

Fig. 1.

KT5823 further increases TSH-stimulated functional NIS expression in PCCL3 rat thyroid cells. A, KT5823 (5 μm) treatment for 16 h increased NIS-mediated RAIU activity in PCCL3 cells treated with TSH (1 mU/ml) chronically (+) or acutely after TSH deprivation (−/+). When PCCL3 cells were cultured in the absence of TSH for more than 5 d (−), KT5823 did not increase RAIU activity. NIS-mediated iodide uptake activity was confirmed by comparing with parallel experiments conducted in the presence of perchlorate, an inhibitor for iodide uptake mediated by NIS. *, Statistically significant difference in RAIU activity (P < 0.05). B, KT5823 treatment increased NIS protein levels in PCCL3 cells with chronic TSH (+) or acute TSH stimulation after TSH deprivation (−/+). A greater extent of increase in 60 kDa NIS compared with 80 kDa NIS with KT5823 treatment suggest modest KT5823-mediated inhibition of NIS glycosylation. In the absence of TSH (−), KT5823 had no effect on NIS protein levels. Equivalent protein loading among samples was monitored by β-actin levels. Experiments were performed twice with triplicates for each RAIU assay.

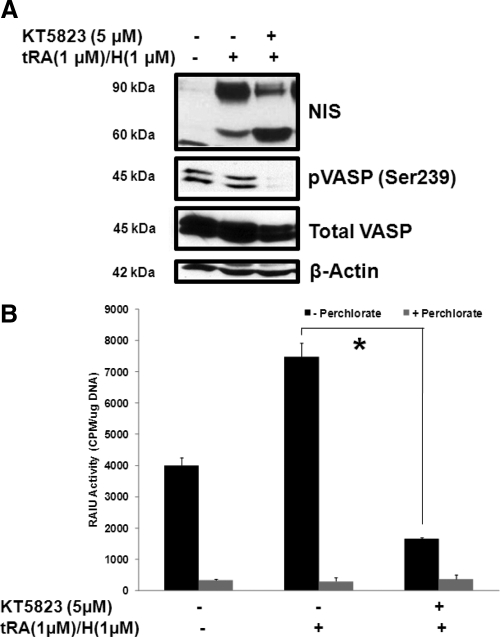

KT5823 accumulates 60 kDa hypoglycosylated NIS protein and reduces RAIU in tRA/H-treated MCF-7 breast cancer cells

To determine whether KT5823 also increases functional NIS expression in breast cancer, MCF-7 cells were treated with tRA (1 μm)/H (1 μm) for 8 h to initiate the induction of endogenous NIS expression followed by the addition of 5 μm KT5823 for 16 h. In contrast to thyroid cells, KT5823 treatment did not increase total NIS protein levels, i.e. the combination of 90 and 60 kDa NIS glycoforms, in MCF-7/tRA/H cells. Instead, KT5823 decreased mature glycosylated 90 kDa NIS and increased hypoglycosylated 60 kDa NIS in tRA/H-treated MCF-7 cells (Fig. 2A). Moreover, KT5823 reduced RAIU activity in tRA/H MCF-7 cells (Fig. 2B) in a dose-dependent manner (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). It is of interest to note that RAIU activity in KT5823 treated tRA/H-MCF-7 cells was much lower than noninduced MCF-7 cells (Fig 2B), despite that total NIS protein level was much higher in KT5823-treated tRA/H MCF-7 cells than noninduced MCF-7 cells (Fig. 2A). This discrepancy suggests that KT5823 may directly or indirectly decrease NIS activity at the posttranslational level in MCF-7 cells. In MCF-7 cells stably expressing exogenous NIS, KT5823 also dramatically decreased RAIU activity yet had little effect on NIS glycosylation status (Supplemental Fig. 2). This discrepancy is most likely due to the low turnover rate of NIS protein because the majority of NIS was already fully glycosylated before KT5823 treatment and cells were not actively synthesizing NIS protein during KT5823 treatment.

Fig. 2.

KT5823 reduces NIS-mediated RAIU activity and results in the accumulation of 60 kDa hypoglycosylated NIS protein. NIS expression in MCF-7 cells was induced by tRA (1 μm)/H (1 μm) for 8 h followed by the addition of KT5823 (5 μm) or DMSO vehicle for another 16 h. A, In contrast to thyroid cells, KT5823 treatment of MCF-7/tRA/H cells resulted in the accumulation of a 60-kDa hypoglycosylated NIS protein with little change in expression of total NIS protein levels (90 and 60 kDa glycoforms combined). Inhibition of protein kinase G/PKA, targets of KT5823, was confirmed by decreased phosphorylation of exogenously expressed VASP at Ser239 [pVASP (Ser239)], whereas total VASP protein levels were equivalent among samples. Equivalent protein loading among samples was monitored by β-actin levels. These results are representative of at least three independent trials with triplicate samples for each RAIU assay. B, KT5823 significantly reduced NIS-mediated RAIU activity in MCF-7/tRA/H cells. NIS-mediated iodide uptake activity was confirmed by comparing with parallel experiments conducted in the presence of perchlorate, an inhibitor for iodide uptake mediated by NIS. *, Statistically significant difference in RAIU activity (P < 0.05). Additional control experiments were performed to examine KT5823 effects on noninduced MCF-7 cells and on tRA/H-induced MCF-7 cells (see Supplemental Fig. 6).

KT5823 accumulated 60 kDa NIS protein in a dose-dependent manner (1–10 μm), and total NIS protein level was decreased at higher KT5823 concentrations (20 μm) (Supplemental Fig. 1). Thus, 60 kDa NIS may be slightly more susceptible to protein degradation than 90 kDa NIS. Indeed, our study showed that 60 kDa NIS was slightly more susceptible to proteasomal-mediated degradation than the 90 kDa form yet had similar susceptibility to lysosomal-mediated degradation compared with 90 kDa NIS (Supplemental Fig. 3). In addition, we noted the degree of 60 kDa NIS accumulation by KT5823 was variable among experiments, most likely due to the reported variable potency of KT5823 among different batches (29).

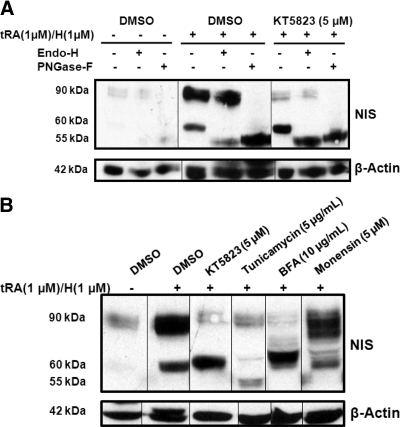

The accumulated 60 kDa NIS protein is core glycosylated and Endo H sensitive

To characterize the accumulated 60 kDa NIS protein, cell lysates were subjected to glycosidases PNGase F and Endo H (Fig. 3A). After digestion with PNGase F, both 90 and 60 kDa NIS glycoforms were deglycosylated to the anticipated 55-kDa molecular mass of nonglycosylated NIS (Fig. 3A, lanes 3, 6, and 9), indicating that both NIS glycoforms were N glycosylated. However, Endo H reduced the molecular mass of the 60-kDa glycoform but not the 90-kDa glycoform of NIS protein (Fig. 3A, lanes 2, 5, and 8), indicating that 90 kDa NIS was complex glycosylated (Endo H resistant), yet the accumulated 60 kDa NIS was an immature, high-mannose glycoform that had not been processed through the Golgi apparatus (Endo H sensitive).

Fig. 3.

The accumulated 60 kDa NIS protein is core glycosylated and Endo H sensitive. NIS expression was induced in MCF-7 cells by tRA (1 μm)/H (1 μm) treatment for 8 h followed by the addition of 5 μm KT5823 or DMSO vehicle for another 16 h. A, Cell lysate was harvested from DMSO-treated MCF-7 cells (lanes 1–3), DMSO-treated MCF-7/tRA/H cells (lanes 4–6), and KT5823-treated MCF-7/tRA/H cells (lanes 7–9) followed by protein digestion with PNGase F or Endo H glycosidase. Although both 90- and 60-kDa NIS glycoforms were deglycosylated by PNGase F to the anticipated 55-kDa nonglycosylated NIS (lanes 6 and 9), the 60-kDa NIS glycoform, but not the 90-kDa glycoform, was sensitive to Endo H digestion (lanes 5 and 8). B, NIS expression was induced by tRA/H treatment of MCF-7 cells for 8 h followed by treatment with inhibitors of the N-linked glycosylation pathway (tunicamycin, BFA, monensin) or DMSO vehicle. Tunicamycin treatment resulted in the anticipated molecular mass of nonglycosylated NIS (55 kDa) (lane 4). NIS from KT5823- and BFA-treated MCF-7/tRA/H cells had comparable molecular masses (∼60 kDa) (lane 3 vs. 5). Most NIS expressed in monensin-treated MCF-7 cells had molecular masses greater than 60 kDa (lane 3 vs. 6). Equivalent protein loading among samples was monitored by β-actin levels. These results are representative of two independent experiments.

KT5823 impedes NIS glycosylation at a regulatory point similar to brefeldin A

NIS glycosylation status in KT5823-treated MCF-7/tRA/H cells was further compared with cells treated with pharmacological inhibitors of the N-linked glycosylation pathway, including tunicamycin (5 μg/ml), brefeldin A (BFA) (10 μg/ml) or monensin (5 μm) (Fig. 3B). Treatment with tunicamycin, an inhibitor of the first step of N-linked glycosylation, resulted in the accumulation of nonglycosylated NIS protein with the expected molecular mass of 55 kDa (Fig. 3B, lane 4). Interestingly, NIS in MCF-7/tRA/H cells treated with BFA, an inhibitor of protein transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus, had a comparable molecular mass with the 60-kDa hypoglycosylated NIS from KT5823-treated MCF-7/tRA/H cells (Fig. 3B, lane 3 vs. 5). This result suggested that BFA and KT5823 may have inhibited NIS glycosylation at similar points along the pathway. MCF-7/tRA/H cells treated with monensin, an inhibitor of medial- to trans-Golgi transport, had NIS glycoforms of molecular masses greater than 60 kDa (Fig. 3B, lane 6), indicating that monensin targeted later stages along the N-linked glycosylation pathway. Taken together, KT5823 most likely inhibited NIS glycosylation after core glycosylation but before its trafficking through the Golgi apparatus. The 90-kDa NIS in treated cells is most likely to be expressed and processed before treatment with KT5823 or each respective inhibitor.

Incomplete NIS glycosylation plays little role in KT5823-mediated reductions in RAIU activity

Because it was previously reported that partially glycosylated and completely nonglycosylated rat NIS mutants have reduced RAIU activity compared with WT rat NIS (30), we hypothesized that incomplete NIS glycosylation accounts for corresponding reductions in RAIU activity and RAIU activity of nonglycosylated hNIS mutants would not be further decreased by KT5823.

As shown in Fig. 4A, replacing the asparagine residue N225, N489, or N502 with glutamine in hNIS resulted in partially glycosylated hNIS mutants. The triple hNIS mutant (N225Q/N489Q/N502Q) was nonglycosylated with the anticipated molecular mass of 55 kDa. KT5823 reduced the ratios of 90 kDa to 60 kDa NIS in cells expressing each single hNIS mutant (Fig. 4A, lanes 5 vs. 6, 7 vs. 8, 9 vs. 10). This indicates that KT5823 does not target a specific N-glycosylated site of NIS but acts on a yet-to-be identified regulatory point along the N-linked glycosylation pathway.

Fig. 4.

Incomplete NIS glycosylation plays little role in KT5823-mediated reductions in RAIU activity. Each or all three putatively glycosylated asparagine residues were replaced with glutamine to generate partially or nonglycosylated hNIS mutants (N225Q, N489Q, N502Q, N225Q/N489Q/N502Q). WT and mutant hNIS were transiently transfected into MCF-7 cells and treated with 5 μm KT5823 or DMSO vehicle for 16 h. A, The N225Q, N489Q, and N502Q single hNIS mutants were partially glycosylated as their molecular weights were reduced compared with that of WT NIS (lanes 5, 7, and 9 vs. lane 3, respectively). The N225Q/N489Q/N502Q triple hNIS mutant was nonglycosylated because it had the anticipated molecular mass of 55 kDa (lane 11 vs. lane 3). KT5823 treatment resulted in the accumulation of hypoglycosylated NIS protein in cells expressing exogenous WT hNIS as well as single hNIS mutants (lane 3 vs. 4; lane 5 vs. 6; lane 7 vs. 8 and lane 9 vs. 10). As expected, KT5823 treatment had no effect on the molecular weight of the triple, nonglycosylated mutant (lane 11 vs. 12). Equivalent protein loading among the samples was monitored by β-actin levels. B, Single hNIS mutants had moderately decreased RAIU activity and the triple hNIS mutant had significantly decreased RAIU activity compared with WT hNIS (lanes 9, 13, 17, and 21 vs. 5). KT5823 treatment significantly reduced RAIU activity of each partially and nonglycosylated hNIS mutant (lane 9 vs. 11; lane 13 vs. 15; lane 17 vs. 19; and lane 21 vs. 23). NIS-mediated iodide uptake activity was confirmed by comparing with the parallel experiments conducted in the presence of perchlorate, an inhibitor for iodide uptake mediated by NIS. *, Statistically significant differences in RAIU activity (P < 0.05). Western blot and RAIU experiments were performed three times, and triplicate samples were included for each RAIU assay.

As shown in Fig. 4B, single hNIS mutants had moderately decreased NIS-mediated RAIU activity compared with WT hNIS, while RAIU activity of the triple hNIS mutant was significantly decreased by more than 50% (Fig. 4B). However, KT5823 further reduced RAIU activity of partially and nonglycosylated hNIS mutants (Fig. 4B), indicating that KT5823-mediated reductions in RAIU activity were not mainly contributed by its effect on the inhibition of NIS complex glycosylation.

KT5823 reduces RAIU activity before inhibiting NIS glycosylation

A temporal profile of NIS expression/activity in KT5823-treated MCF-7/tRA/H cells was investigated. MCF-7 cells were treated with tRA/H for 12 h for the induction of NIS followed by treatment with 5 μm KT5823 or DMSO vehicle for an additional 0.5, 4, or 16 h, such that NIS was induced by tRA/H for the duration of 12.5, 16, or 28 h, respectively (Fig. 5A). As shown in Fig. 5, RAIU activity was decreased by 51.9% within 0.5 h of KT5823 treatment (Fig. 5B) despite no corresponding changes in NIS glycosylation status or NIS protein levels (Fig. 5C, lanes 2 vs. 3). KT5823's effect on NIS glycosylation status did not become evident until 16 h after treatment. A further reduction in RAIU activity was noted after 16 h of KT5823 treatment compared with 0.5 or 4 h of KT5823 treatment. These data indicate that the early reduction of RAIU activity by KT5823 is independent of its inhibition of NIS glycosylation.

Fig. 5.

KT5823 reduces NIS-mediated RAIU activity before inhibiting NIS glycosylation. A, NIS expression was induced in MCF-7 cells by tRA (1 μm)/H (1 μm) (solid black lines) for 12 h followed by the addition of 5 μm KT5823 or DMSO vehicle (solid gray lines) for another 0.5, 4.0, or 16.0 h, as depicted in the diagram. B, NIS-mediated RAIU activity significantly decreased after 0.5 or 4 h of KT5823 (lane 3 vs. 5 and lane 9 vs.11, respectively) and further decreased after 16 h of KT5823 treatment (lane 15 vs. 17). NIS-mediated iodide uptake activity was confirmed by comparing with parallel experiments conducted in the presence of perchlorate, an inhibitor for iodide uptake mediated by NIS. *, Statistically significant differences in RAIU activity (P < 0.05). C, No significant changes in NIS protein were observed after 0.5 h of KT5823 treatment (lane 2 vs. 3), and the accumulation of 60 kDa hypoglycosylated NIS protein was not evident until 16 h after KT5823 treatment (lane 8 vs. 9). Anti-β-actin antibodies were used to monitor the equal loading of protein among samples. These results represent two independent experiments with triplicate samples for each RAIU assay.

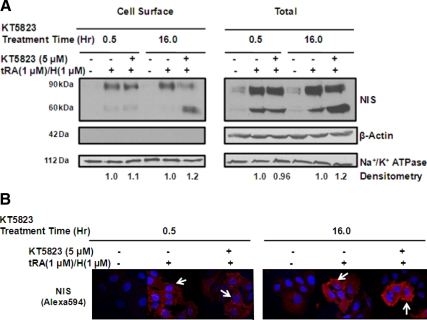

KT5823 does not alter cell surface NIS levels or iodide efflux rate

Because NIS must be localized at the cell surface to confer functional iodide uptake, we evaluated whether KT5823 decreased RAIU activity by impairing NIS cell surface trafficking such that less functional NIS was available at the cell surface. As shown in Fig. 6A, cell surface NIS protein levels were not altered by KT5823. Although 16 h of KT5823 treatment did result in accumulation of hypoglycosylated NIS protein, the 60-kDa hypoglycosylated NIS glycoform was capable of trafficking to the cell surface. Lack of intracellular β-actin protein in the cell surface protein fraction ruled out the possibility of contaminating intracellular proteins. This finding was further confirmed by immunofluorescence labeling of hNIS protein examined under the confocal microscope (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

KT5823 does not reduce cell surface NIS levels. NIS expression was induced in MCF-7 cells for 12 h by tRA (1 μm)/H (1 μm) followed by the addition of 5 μm KT5823 or DMSO vehicle for another 0.5 or 16 h. Cell surface proteins were biotinylated and isolated from intracellular proteins by streptavidin-coated beads followed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. A, Cell surface or total NIS levels were not decreased by 0.5 or 16 h KT5823 treatments (lanes 2 vs. 3; lane 5 vs. 6; lane 8 vs. 9; and lanes 11 vs. 12). Note that both mature glycosylated 90-kDa and hypoglycosylated 60-kDa NIS glycoforms were able to traffic to the cell surface. The lack of intracellular β-actin in the cell surface fraction ruled out the possibility of contamination with intracellular proteins. Na+/K+ ATPase levels indicated equivalent protein loading among samples. B, Immunofluorescence labeling of NIS protein in MCF-7/tRA/H cells confirmed that KT5823 did not reduce cell surface NIS levels (arrows). (Magnification, ×600). These results are representative of two sets of independent experiments.

Because RAIU activity represents the steady-state equilibrium between iodide uptake and iodide efflux, we also evaluated whether increased iodide efflux rates may contribute to KT5823-mediated reductions in RAIU activity. However, iodide efflux rates did not change after 0.5 or 16 h of KT5823 treatment (Supplemental Fig. 4). Because KT5823 did not decrease cell surface NIS levels or increase iodide efflux rates, KT5823 most likely decreased RAIU activity by decreasing iodide influx rate.

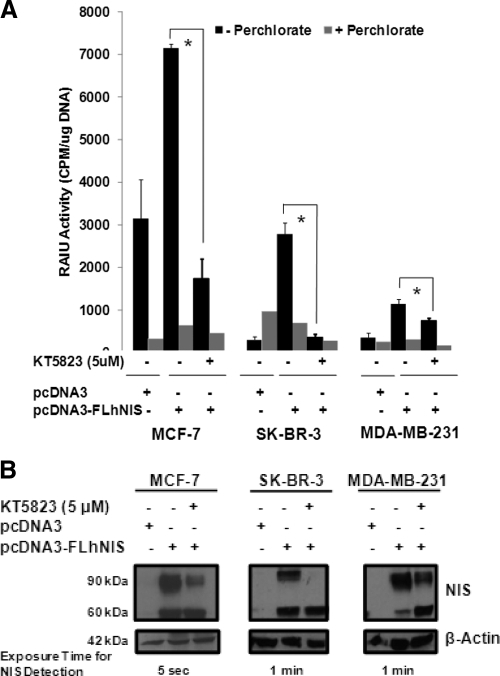

KT5823 inhibits activity and glycosylation of exogenous NIS expressed in three human breast cancer cell lines

To ensure that the observed KT5823-mediated effects on RAIU activity and NIS glycosylation were not restricted to MCF-7/tRA/H breast cancer cells, NIS-mediated RAIU activity and NIS glycosylation were examined in KT5823-treated MCF-7, SK-BR-3, and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells transiently expressing exogenous hNIS. KT5823 significantly reduced NIS-mediated RAIU activity (Fig. 7A) and inhibited NIS glycosylation (Fig. 7B) in all three human breast cancer cell lines. It is interesting to note that iodide uptake activity is very modest in MDA-MB-231 cells, albeit its NIS protein level is comparable with SK-BR-3 cells. This is consistent with our previous study showing that NIS protein levels are not always correlated with iodide uptake activity among different cells, most likely due to the differences in their rates of iodide efflux and/or cellular context that may modulate NIS activity (31). Finally, KT5823 also decreased RAIU activity and altered the NIS glycosylation status in hNIS-transfected HEK293 cells (Supplemental Fig. 5), suggesting that KT5823 exerts differential NIS modulation in thyroid vs. nonthyroid cells.

Fig. 7.

KT5823 reduces RAIU activity and inhibits NIS glycosylation in all human breast cancer cells examined. MCF-7, SK-BR-3, and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells were transiently transfected with exogenous FLhNIS followed by treatment with 5 μm KT5823 or DMSO vehicle for 16 h. A, KT5823 significantly reduced NIS-mediated RAIU activity in each human breast cancer cell line expressing exogenous hNIS. NIS-mediated iodide uptake activity was confirmed by comparing with parallel experiments conducted in the presence of perchlorate, an inhibitor for iodide uptake mediated by NIS. *, Statistically significant differences in RAIU activity (P < 0.05). B, KT5823 inhibited glycosylation of exogenous hNIS in each human breast cancer cell line. NIS expression was variable among breast cancer cell lines, as indicated by differences in the exposure times for NIS detection by Western blot. β-Actin served as a loading control to ensure equal protein loading among samples. Triplicate samples were included for RAIU assays.

Discussion

In this study, we found that KT5823 differentially regulated NIS expression, activity, and glycosylation between thyroid and breast cancer cells. Whereas KT5823 further increased TSH-induced NIS expression/function in PCCL3 rat thyroid cells, it reduced RAIU activity in tRA/H-treated MCF-7 human breast cells within 0.5 h of treatment. Thus, KT5823 appears to reduce NIS activity at the posttranslational level in breast cancer cells but not in thyroid cells. Moreover, a longer KT5823 treatment accumulated hypoglycosylated NIS in breast cancer cells to a much greater extent than in thyroid cells. The hypoglycosylated NIS was characterized for the first time and found to be core glycosylated, not yet processed through the Golgi apparatus, but capable of trafficking to the cell surface. Finally, KT5823-mediated effects on NIS activity and glycosylation were also observed in other breast cancer cells as well as human embryonic kidney cells expressing exogenous NIS.

For thyroid cancer patients prescribed for targeted radioiodine therapy, thyroidal NIS expression/function is selectively increased by administration of recombinant hTSH or by T4 withdrawal to elevate serum TSH levels. Indeed, TSH not only stimulates NIS expression (14–18) but has also been reported to increase NIS protein half-life and cell surface localization (32). However, novel approaches are needed to selectively increase NIS expression/function for patients with poorly differentiated thyroid cancers, which have reduced TSH receptor levels and/or impaired TSH-stimulated signaling pathways. In the thyroid, constitutively active signaling that contributes to malignant tumor progression, such as MEK or phosphoinositide-3 kinase/AKT activation, is involved in the negative regulation of NIS expression, i.e. malignant thyroid tumors almost always have reduced NIS expression. Consequently, pharmacological inhibitors targeting these signaling not only can serve as a chemotherapeutic agent to halt tumor progression but also increase NIS expression/function to improve the efficacy of radioiodine therapy.

In contrast to thyroid, increased NIS expression has been reported in breast tumors compared with nonmalignant tissue (2, 3). However, the functional expression level of NIS in most breast tumors is insufficient to facilitate radioiodine therapy (5, 6). Among all reagents reported, a combination treatment of tRA and glucocorticoids consistently induces NIS expression in MCF-7 cells (10–13) and MCF-7 cell xenografts (12) as well as the mammary glands of some mice (12). Unfortunately, Kogai et al. (10, 33) stated that the doses of tRA used to maximize NIS induction in MCF-7 cell xenografts in vivo are more than 10-fold greater than the tolerable tRA dose used in humans. Furthermore, it is yet to be determined whether the extent of iodide accumulation induced by the combination treatment of tRA and glucorticoids is sufficient for effective therapy. Accordingly, there is a need to identify pharmacological reagents that can selectively increase NIS expression/function in breast cancers.

Other than tRA, most agents have not been shown to consistently increase basal NIS expression in MCF-7 cells (34), which may be due to the inherent genomic instability and heterogeneity of the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line (35, 36). We observed that basal NIS protein levels vary among different MCF-7 cell populations (lane 1 in Fig. 2B vs. lane 1 in Fig. 3B) and appear to be independent of cell passage. Nevertheless, we noted that NIS expression/function is increased in MCF-7 cells cultured in 5% charcoal-stripped FBS compared with MCF-7 cells cultured in 10% FBS (Figs. 3B, lane 1, vs. 4A, lane 1), suggesting the presence of yet-to-be identified negative regulator(s) of NIS expression in FBS. Pharmacological reagents, such as AG490 (Janus kinase inhibitor), ML3403 (p38 MAPK inhibitor), and Rottlerin (inhibitor of protein kinase Cδ and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase III), have also been shown to significantly reduce basal as well as tRA-induced NIS mRNA levels in MCF-7 cells (20).

NIS modulation in both thyroid and breast appears to occur mainly at the expression level. However, a few pharmacologic reagents have been reported to modulate NIS at the posttranslational level (20, 22). In this study, we showed that KT5823 drastically reduced NIS-mediated iodide uptake activity within only 0.5 h of treatment in MCF-7/tRA/H cells, suggesting that KT5823 directly or indirectly modulated NIS or NIS-associated proteins at the posttranslational level. Riedel et al. (32) initially reported that NIS is a phosphoprotein. We later identified several phosphorylated amino acid residues in rNIS expressed in HEK293 cells and further suggested that NIS activity may be modulated by the phosphorylation status of Ser-43 and Ser-581 of rNIS (37). It is interesting to note that protein kinase G and other targets of KT5823, such as protein kinase C and PKA, are among the candidate kinases predicted to phosphorylate rNIS at Ser-43 or Ser-581. However, further studies should be conducted to investigate whether NIS phosphorylation status is altered by KT5823. Taken together, KT5823 will be useful in elucidating signaling that directly or indirectly modulates NIS-mediated RAIU activity in breast cancer cells.

NIS glycoprotein often presents as two major glycoforms, suggesting that NIS glycosylation is mainly regulated at a single step along the N-linked glycosylation pathway. However, the nature of hypoglycosylated NIS has not been previously characterized, and the underlying mechanism responsible for the accumulation of hypoglycosylated NIS remains elusive. The hypoglycosylated NIS is core glycosylated but has not been processed through the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 3A). We also showed that KT5823 impedes NIS complex glycosylation at a regulatory point similar to BFA along the N-linked glycosylation pathway (Fig. 3B), rather than targeting a specific N-glycosylated site of NIS (Fig. 4A). It has been reported that hypoglycosylation can be contributed by steric hindrance of client proteins during folding that prevents its processing by glycosylation-associated enzymes (38) or inhibition of the expression/activity of glycosylation-associated enzymes (39). Accordingly, KT5823 may modulate NIS protein folding or expression/activity of glycosylation-associated enzymes along the N-linked glycosylation pathway.

In summary, we have added KT5823 to the growing list of pharmacological reagents that differentially modulate NIS expression/activity between thyroid and breast cancer cells. Because KT5823 has multiple targets (40), one should be cautious that targets of KT5823 that modulate NIS expression levels in thyroid cells may not be the same targets that modulate NIS activity and glycosylation in breast cancer cells. Nevertheless, KT5823 will serve as a valuable tool in uncovering the signaling mechanisms that modulate NIS expression in thyroid cells and NIS activity/glycosylation in breast cancer cells. Moreover, our study is the first to characterize hypoglycosylated NIS protein and to explore possible mechanisms underlying the accumulation of hypoglycosylated NIS in breast cancer cells. We showed that hypoglycosylated NIS is capable of trafficking to the cell surface, although it is yet to be determined whether the activity of hypoglycosylated NIS is comparable with that of mature glycosylated NIS. Indeed, it remains uncertain whether further reductions in RAIU activity with longer KT5823 treatments (Fig. 5) are contributed by incomplete NIS glycosylation. A better understanding of the underlying mechanisms by which KT5823 potently reduces NIS-mediated RAIU activity may lead to novel strategies for selectively increasing NIS-mediated RAIU activity in NIS-positive breast tumors. Finally, it is also of interest to examine whether KT5823 has similar effects on other sodium-dependent transporters.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01CA124570 (project 3 leader: S.J.), T32GM068412 (trainee: S.B.), and the Science Foundation Ireland (to A.S.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BFA

- Brefeldin A

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- Endo H

- endoglycosidase H

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- FLhNIS

- full-length human NIS

- HEK293

- human embryonic kidney 293

- hNIS

- human NIS

- MEK

- MAP/ERK kinase

- NIS

- Na+/I− symporter

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- PNGase F

- peptide-N(4)-(N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminyl) asparagine amidase F

- RAIU

- radioactive iodide uptake

- rNIS

- rat NIS

- tRA

- trans-retinoic acid

- TSH

- thyroid-stimulating hormone

- VASP

- vasodilator stimulated protein

- WT

- wild type.

References

- 1. Mazzaferri EL, Kloos RT. 2001. Current approaches to primary therapy for papillary and follicular thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:1447–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tazebay UH, Wapnir IL, Levy O, Dohan O, Zuckier LS, Zhao QH, Deng HF, Amenta PS, Fineberg S, Pestell RG, Carrasco N. 2000. The mammary gland iodide transporter is expressed during lactation and in breast cancer. Nat Med 6:871–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wapnir IL, van de Rijn M, Nowels K, Amenta PS, Walton K, Montogomery K, Greco RS, Dohán R, Carrasco N. 2003. Immunohistochemical profile of the sodium/iodide symporter in thyroid, breast and other carcinomas using high density tissue microarray and conventional sections. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:1880–1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Renier C, Vogel H, Offor O, Yao C, Wapnir I. 2010. Breast cancer brain metastases express the sodium iodide symporter. J Neurooncol 96:331–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Renier C, Yao C, Goris M, Ghosh M, Katznelson L, Nowles K, Gambhir SS, Wapnir I. 2009. Endogenous NIS expression in triple-negative breast cancers. Ann Surg Oncol 16:962–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wapnir IL, Goris M, Yudd A, Dohan O, Adelman D, Nowels K, Carrasco N. 2004. The Na+/I− symporter mediates iodide uptake in breast cancer metastases and can be selectively down-regulated in the thyroid. Clin Cancer Res 10:4294–4302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moon DH, Lee JL, Park KY, Park KK, Ahn SH, Pai MS, Chang H, Lee HK, Ahn IM. 2001. Correlation between 99mTc-pertechnetate uptakes and expression of human sodium iodide symporter in breast tumor tissues. Nucl Med Biol 28:829–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peyrottes I, Navarro V, Ondo-Mendez A, Marcellin D, Bellanger L, Marsault R, Lindenthal S, Ettore F, Darcourt J, Pourcher T. 2009. Immunoanalysis indicates that the sodium iodide symporter is not overexpressed in intracellular compartments in thyroid and breast cancers. Eur J Endocrinol 160:215–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kogai T, Schultz JJ, Johnson LS, Huang M, Brent GA. 2000. Retinoic acid induces sodium/iodide symporter gene expression and radioiodide uptake in the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:8519–8524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kogai T, Kanamoto Y, Li AI, Che LH, Ohashi E, Taki K, Chandraratna RA, Saito T, Brent GA. 2005. Differential regulation of sodium/iodide symporter gene expression by nuclear receptor ligands in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Endocrinology 146:3059–3069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Unterholzner S, Willhauk MJ, Cengic N, Schütz M, Göke B, Morris JC, Spitzweg C. 2006. Dexamethasone stimulation of retinoic acid-induced sodium iodide symporter expression and cytotoxicity of 131-I in breast cancer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:69–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Willhauk MJ, Sharif-Samani B, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R, Wunderlich N, Göke B, Morris JC, Spitzweg C. 2008. Functional sodium iodide symporter expression in breast cancer xenografts in vivo after systemic treatment with retinoic acid and dexamethasone. Breast Cancer Res Treat 109:263–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dohán O, de la Vieja A, Carrasco N. 2006. Hydrocortisone and purinergic signaling stimulate sodium/iodide symporter (NIS)-mediated iodide transport in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol 20:1121–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weiss SJ, Philip NJ, Ambesi-Impiombato FS, Grollman EF. 1984. Thyrotropin stimulated iodide transport mediated by adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate and dependent on protein synthesis. Endocrinology 114:1099–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaminsky SM, Levy O, Salvador C, Dai G, Carrasco N. 1994. Na+ I− symporter activity is present in membrane vesicles from thyrotropin-deprived non-I(−)-transporting cultured thyroid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:3789–3793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kogai T, Endo T, Saito T, Miyazaki A, Kawaguchi A, Onaya T. 1997. Regulation by thyroid-stimulating hormone of sodium/iodide symporter gene expression and protein levels in FRTL-5 cells. Endocrinology 138:2227–2232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levy O, Dai G, Riedel C, Ginter CS, Paul EM, Lebowitz AN, Carrasco N. 1997. Characterization of the thyroid Na+/I− symporter with an anti-COOH terminus antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:5568–5573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saito T, Endo T, Kawaguchi A, Ikeda M, Nakazato M, Kogai T, Onaya T. 1997. Increased expression of the Na+/I− symporter in cultured human thyroid cells exposed to thyrotropin and in Graves' thyroid tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:3331–3336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schmutzler C, Winzer R, Meissner-Weigl J, Köhrle J. 1997. Retinoic acid increases sodium/iodide symporter mRNA levels in human thyroid cancer cell lines and suppresses expression of functional symporter in non-transformed FRTL-5 rat thyroid cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 240:832–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kogai T, Ohashi E, Jacobs MS, Sajid-Crockett S, Fisher ML, Kanamoto Y, Brent GA. 2008. Retinoic acid stimulation of the sodium/iodide symporter in MCF-7 breast cancer cells is meditated by the insulin growth factor-I/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:1884–1892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Knauf JA, Kuroda H, Basu S, Fagin JA. 2003. RET/PTC-induced dedifferentiation of thyroid cells is mediated through Y1062 signaling through SHC-RAS-MAP kinase. Oncogene 22:4406–4412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vadysirisack DD, Venkateswaran A, Zhang Z, Jhiang SM. 2007. MEK signaling modulates sodium iodide symporter at multiple levels and in a paradoxical manner. Endocr Relat Cancer 14:421–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fozzatti L, Vélez ML, Lucero AM, Nicola JP, Mascanfroni ID, Macció DR, Pellizas CG, Roth GA, Masini-Repiso AM. 2007. Endogenous thyrocyte-produced nitric oxide inhibits iodide uptake and thyroid-specific gene expression in FRTL-5 thyroid cells. J Endocrinol 192:627–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smanik PA, Liu Q, Furminger TL, Ryu K, Xing S, Mazzaferri EL, Jhiang SM. 1996. Cloning of the human sodium iodide symporter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 226:339–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Knostman KA, Cho JY, Ryu KY, Lin X, McCubrey JA, Hla T, Liu CH, Di Carlo E, Keri R, Zhang M, Hwang DY, Kisseberth WC, Capen CC, Jhiang SM. 2004. Signaling through 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate and phosphoinositide-3 kinase induces sodium/iodide symporter expression in breast cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:5196–5203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jhiang SM, Cho JY, Ryu KY, DeYoung BR, Smanik PA, McGaughy VR, Fischer AH, Mazzaferri EL. 1998. An immunohistochemical study of Na+/I− symporter in human thyroid tissues and salivary gland tissues. Endocrinology 139:4416–4419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smolenski A, Bachmann C, Reinhard K, Hönig-Liedl P, Jarchau T, Hoschuetzky H, Walter U. 1998. Functional analysis of cGMP-dependent protein kinases I and II as mediators of NO/cGMP effects. J Biol Chem 273:20029–20035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marsee DK, Venkateswaran A, Tao H, Vadysirisack D, Zhang Z, Vandre DD, Jhiang SM. 2004. Inhibition of heat shock protein 90, a novel RET/PTC1-associated protein, increases radioiodide accumulation in thyroid cells. J Biol Chem 279:43990–43997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Burkhardt M, Glazova M, Gambaryan S, Vollkommer T, Butt E, Bader B, Heermeier K, Lincoln TM, Walter U, Palmetshofer A. 2000. KT5823 inhibits cGMP-dependent protein kinase activity in vitro but not in intact human platelets and rat mesangial cells. J Biol Chem 275:33536–33541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Levy O, De la Vieja A, Ginter CS, Riedel C, Dai G, Carrasco N. 1998. N-linked glycosylation of the thyroid Na+/I− symporter (NIS). J Biol Chem 273:22657–22663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vadysirisack DD, Shen DH, Jhiang SM. 2006. Correlation of Na+/I− symporter expression and activity: implications of Na+/I− symporter as an imaging reporter gene. J Nucl Med 47:182–190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Riedel C, Levy O, Carrasco N. 2001. Post-transcriptional regulation of the sodium/iodide symporter by thyrotropin. J Biol Chem 276:21458–21463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kogai T, Kanamoto Y, Che LH, Taki K, Moatamed F, Schultz JJ, Brent GA. 2004. Systemic retinoic acid treatment induces sodium/iodide symporter expression and radioiodide uptake in mouse breast cancer models. Cancer Res 64:415–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arturi F, Ferretti E, Presta I, Mattei T, Scipioni A, Scarpelli D, Bruno R, Lacroix L, Tosi E, Gulino A, Russo D, Filetti S. 2005. Regulation of iodide uptake and sodium/iodide symporter expression in the MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:2321–2326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Osborne CK, Hobbs K, Trent JM. 1987. Biological differences among MCF-7 human breast cancer cell lines from different laboratories. Breast Cancer Res Treat 9:111–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Resnicoff M, Medrano EE, Podhajcer OL, Bravo AI, Bover L, Mordoh J. 1987. Subpopulations of MCF7 cells separated by Percoll gradient centrifugation: a model to analyze the heterogeneity of human breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84:7295–7299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vadysirisack DD, Chen ES, Zhang Z, Tsai MD, Chang GD, Jhiang SM. 2007. Identification of in vivo phosphorylation sites and their functional significance in the sodium iodide symporter. J Biol Chem 282:36820–36828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Suzuki N, Lee YC. 2004. Site-specific N-glycosylation of chicken serum IgG. Glycobiology 14:275–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bolander FF., Jr 2000. Rapid hormonal regulation of N-acetylglucosamine transferase I. J Mol Endocrinol 24:377–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smolenski A, Burkhardt AM, Eigenthaler M, Butt E, Gambaryan S, Lohmann SM, Walter U. 1998. Functional analysis of cGMP-dependent protein kinases I and II as mediators of NO/cGMP effects. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 358:134–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]