Knockdown of NOBOX in early embryos results in impaired embryonic development and reduced expression of genes important for early embryogenesis.

Abstract

Newborn ovary homeobox (NOBOX) is an oocyte-specific transcription factor essential for folliculogenesis and expression of many germ cell-specific genes in mice. Here we report the characterization of the bovine NOBOX gene and its role in early embryogenesis. The cloned cDNA for bovine NOBOX contains an open reading frame encoding a protein of 500 amino acids with a conserved homeodomain. mRNA for NOBOX is preferentially expressed in ovaries and undetectable by RT-PCR in somatic tissues examined. NOBOX protein is present in oocytes throughout folliculogenesis. NOBOX is expressed in a stage-specific manner during oocyte maturation and early embryonic development and of maternal origin. Knockdown of NOBOX in early embryos using small interfering RNA demonstrated that NOBOX is required for embryonic development to the blastocyst stage. Depletion of NOBOX in early embryos caused significant down-regulation of genes associated with transcriptional regulation, signal transduction, and cell cycle regulation during embryonic genome activation. In addition, NOBOX depletion in early embryos reduced expression of pluripotency genes (POU5F1/OCT4 and NANOG) and number of inner cell mass cells in embryos that reached the blastocyst stage. This study demonstrates that NOBOX is an essential maternal-derived transcription factor during bovine early embryogenesis, which functions in regulation of embryonic genome activation, pluripotency gene expression, and blastocyst cell allocation.

During oogenesis, there is an accumulation and storage of maternal RNAs and proteins that are obligatory not only for successful folliculogenesis and germ cell maturation, but also for activation of the embryonic genome and subsequent early embryonic development (1, 2). A growing body of evidence supports a role for oocyte-derived growth factors, such as growth differentiation factor-9 and bone morphogenetic protein-15 in regulation of ovarian follicular development, and several oocyte-specific transcription factors have been identified that are required for follicle formation or progression during development. For example, FIGLA (Factor in the germline α), an oocyte-specific basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor required for primordial follicle formation (3), is implicated in the coordinate expression of the three zona pellucida genes (Zp1, Zp2, Zp3) essential for fertilization (4). However, less is known about maternal regulation of early embryonic development.

The time period during development spanning from fertilization until when control of early embryogenesis changes from regulation by oocyte-derived factors to regulation by products of the embryonic genome is referred to as the “maternal-to-embryonic transition.” The products of numerous maternal-effect genes transcribed and stored during oogenesis mediate this transition. Maternal antigen that embryos required (Mater or Nlrp5) is the first oocyte-specific maternal factor identified in mouse and is known to be essential for the development of embryos beyond the two-cell stage (5). The roles of additional oocyte-specific genes Zar1 (Zygotic arrest 1) and Npm2 (Nucleoplasmin 2) in early embryonic development have been revealed from gene-targeting studies in mice. Zar1-knockout embryos are arrested at the one-cell stage and show marked reduction in the synthesis of the transcription-requiring complex during the maternal-to-embryonic transition (6). Npm2-knockout females have fertility defects due to reduced cleavage, absence of coalesced nucleolar structures, and heterochromatin loss, suggesting that Npm2 is a critical chromatin remodeling during early embryonic development (7). Recently, another maternal-effect gene, FILIA, was discovered in mice. FILIA binds to MATER and is essential for maintaining euploidy during cleavage-stage embryogenesis (8).

Understanding of maternal-effect genes required for early embryogenesis has clearly been enhanced through results of gene targeting studies in mice. However, due to inherent species-specific differences in the duration and number of cell cycles required for embryonic genome activation (EGA) and completion of the maternal-to-embryonic transition in mice vs. humans and cattle or other livestock species (9), the regulatory mechanisms and maternal-effect genes mediating this transition may vary. Furthermore, understanding of the regulatory role of many known oocyte-derived transcription factors in early embryonic development through gene-targeting models is limited due to defective follicular development and female sterility. One such transcription factor is newborn ovary homeobox (NOBOX)-encoding gene. NOBOX mRNA and protein are preferentially expressed in the germ cells throughout folliculogenesis (10). Female mice lacking NOBOX are infertile due to postnatal oocyte loss and a disrupted transition in follicular development from primordial to primary follicle (11). Furthermore, expression of numerous genes in oocytes linked to female fertility (e.g. Pou5f1/Oct4, Gdf9, Bmp15, Zar1, and Mos) and certain microRNAs were drastically reduced in newborn ovaries that lack NOBOX (11, 12). Recently, mutations in the NOBOX gene that are associated with premature ovarian failure in humans have been identified (13, 14). However, despite its established role in control of oocyte gene expression, the requirement of NOBOX for early embryonic development has not been investigated.

We hypothesize that maternal (oocyte-derived) NOBOX also is required for early embryonic development and expression of NOBOX-responsive genes at EGA critical for normal blastocyst development. The objectives of the present studies were 1) to clone and determine intraovarian localization of the bovine NOBOX gene, and 2) to elucidate the functional role of bovine NOBOX in early embryonic development.

Materials and Methods

Tissue collection

Bovine tissue samples including adult ovary, adult testis, liver, thymus, kidney, muscle, heart, cortex (brain), spleen, pituitary, adrenal, lung, fetal ovary, and fetal testis were obtained at a local slaughterhouse. Age of fetuses from which fetal ovaries were collected was estimated by measuring the crown-rump length (15). Granulosa cells (16) and cumulus cells (17) were isolated as described. All samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 C until use.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After treatment with TURBO™ DNaseI (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX), reverse transcription was performed on approximately 1 μg of isolated RNA in 20 μl of reaction solution using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The RT-PCR was performed by denaturation at 95 C for 3 min followed by 35 cycles of 95 C for 30 sec, 58 C for 45 sec, and 72 C for 90 sec and final extension at 72 C for 10 min. The amplified products were separated through a 1% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Amplification of cDNA for bovine ribosomal protein L19 (RPL19) was used as a positive control for RNA quality and RT. See Supplemental Table.1 published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://end.endojournals.org for the list of primer sequences.

Cloning of bovine NOBOX cDNA

Based on the predicted cDNA sequence for the bovine NOBOX gene in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Database, primers were designed (Supplemental Table 1) to amplify 1500 bp fragment from bovine fetal ovary (enriched source of oocytes). The amplified cDNA fragment (1500 bp) was cloned using a TOPO cloning kit (Invitrogen) and completely sequenced. Gene-specific rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) primers (Supplemental Table 1) were designed based on the obtained sequence, and 5′- and 3′-RACE was performed to extend the 5′- and 3′-end of the cDNA sequence using the second-generation 5′/3′ RACE kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Northern blot analysis

For determining the size of the bovine NOBOX transcript, Northern blot analysis was performed as described previously (18).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed using Ultrasensitive avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex staining kit (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, approximately 10-μm serial sections of bovine fetal ovary (d 230 of gestation) were prepared and mounted onto polylysine-coated slides. The sections were deparaffinized in xylene and then rehydrated in graded alcohol. After treatment with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol to eliminate endogenous peroxidase activity, the sections were blocked for 30 min with blocking buffer. After blocking, rabbit polyclonal anti-NOBOX antibody (ab41612; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) diluted 1:100 in blocking buffer was applied to each section and incubated for 1 h. The sections were then washed for 15 min in PBS and incubated with biotinylated antirabbit IgG for 1 h, followed by incubation with avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex reagent for 1 h at room temperature. The sections were developed using a metal-enhanced DAB Substrate kit (Pierce) for 2–10 min and were then counterstained with VECTOR Hematoxylin QS (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and mounted with Permount (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ). For negative controls, sections were incubated in the absence of anti-NOBOX antibody.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

The oocytes and embryo samples used in the experiment included germinal vesicle (GV)- and metaphase II (MII)-stage oocytes and pronuclear, two-cell, four-cell, eight-cell, 16-cell, and morula- and blastocyst-stage embryos (n = 5 pools of 10 embryos) generated by in vitro fertilization of abattoir-derived oocytes as described elsewhere (19). Procedures used for RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative real-time PCR analysis of mRNA abundance during oocyte maturation and early embryonic development were conducted as described previously (18, 19). See Supplemental Table 1 for the list of primer sequences.

RNA interference (RNAi) experiments

Knockdown of endogenous NOBOX in bovine embryos was performed via microinjection of NOBOX small interfering RNA (siRNA). RNAi experiments were conducted according to our published procedures (18, 20, 21) with modifications noted herein. The publicly available siRNA design algorithm (siRNA target finder, Ambion) was used to design four distinct siRNA species targeting the open reading frame of bovine NOBOX mRNA (designated as siRNA species 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively). The candidate siRNA species were interrogated by using the basic local alignment tool program (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) to rule out homology to any other known genes in the bovine expressed sequence tag and genomic database. The NOBOX siRNA species were synthesized using the Silencer siRNA construction kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sense and antisense oligonucleotide template sequences for both siRNA species are given in Supplemental Table 1. Procedures for in vitro maturation of oocytes (obtained from abattoir-derived ovaries) and in vitro fertilization to generate zygotes for microinjection, and for subsequent embryo culture, were conducted basically as described elsewhere (19). Presumptive zygotes collected at 16–18 h post insemination (hpi) were used in all microinjection experiments. Each individual siRNA species was validated for efficacy of NOBOX mRNA knockdown in early embryos. Presumptive zygotes were microinjected with approximately 20 pl of individual NOBOX siRNA species (25 μm concentration each), and four-cell embryos were collected at 42–44 hpi for real-time PCR analysis of NOBOX mRNA. Uninjected embryos and embryos injected with a negative siRNA (universal control no. 1; Ambion) were used as control groups (n = 4 pools of 10 embryos per treatment). Efficacy of NOBOX siRNA in reducing NOBOX protein in early embryos was determined by NOBOX immunostaining of eight-cell embryos collected 72 hpi (n = 10–15 embryos per group). The development of the uninjected or injected embryos (with NOBOX siRNA or negative control siRNA) was evaluated by recording the proportion of embryos that cleaved (48 h after insemination) and reached eight- to 16-cell stage (72 h after insemination) and blastocyst stage (7 d after insemination). Each group contained 25–30 embryos per treatment (n = 4 replicates).

Immunofluorescent staining

Immunoflorescent staining was performed according to previously published procedures (22) with modifications noted herein. Oocytes and embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. Fixed oocytes and embryos were washed in PBS three times and quenched for 5 min with 0.05% (wt/vol) solution of sodium borohydrate in PBS to reduce fluorescence background. They were washed again in PBS three times and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min. After washing with PBS, samples were incubated in blocking solution (2% BSA and 10% normal goat serum in PBS) for at least 1 h. Immunoflorescent staining was performed by incubating samples in rabbit polyclonal anti-NOBOX antibody diluted 1:50 in PBS containing 0.5% (wt/vol) BSA and 0.1% (wt/vol) NaN3 overnight at 4 C. Oocytes and embryos were then washed for 45 min in PBS containing 0.1% (wt/vol) Tween-20 at room temperature, transferred to the fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody (F9887; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) diluted in PBS containing 0.5% (wt/vol) BSA and 3% normal goat serum and incubated for 60 min. Finally they were washed with PBS containing 0.1% (wt/vol) Tween 20 for 30 min and mounted on slides using an antifading medium containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI; Invitrogen). At least 10 oocytes/embryo were processed for each stage per treatment, and experiments were replicated at least three times. For negative control, the oocytes and embryos were incubated in the absence of anti-NOBOX antibody.

Identification of zygotic transcripts in eight-cell embryos by microarray analysis

In vitro maturation of oocytes and in vitro fertilization were conducted as described previously (19). Presumptive zygotes were cultured in potassium simplex optimization medium containing 0.3% BSA in the presence or absence of 50 mg/ml of the transcription inhibitor α-amanitin, and eight-cell embryos were collected 52 h later. Groups of eight-cell embryos were pooled within treatment (n = 10 embryos per pool; n = 3 replicates for α-amanitin and n = 4 replicates for untreated controls) and frozen in 20 μl PicoPure lysis buffer, and RNA purification was performed using PicoPure RNA isolation kit. Purified RNA was subjected to two rounds of reverse transcription and in vitro transcription with biotinylated nucleotides according to Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) two-cycle eukaryotic target labeling protocol. Biotin-labeled cRNA samples were fragmented and hybridized to Affymetrix Bovine Genome Arrays at the University of Pennsylvania Microarray Core Facility. Raw probe level data were imported into Affymetrix Expression Console 1.1, and a quantile normalization and summarization were performed using the Robust Multichip Analysis function. For Significant Analysis of Microarray, analysis probe sets were first filtered by detection calls using Affymetrix MAS 5.0. Only those probe sets called “Present” in at least three of four replicates were considered for Significant Analysis of Microarray. Probe sets identified as differentially expressed at the False Discovery Rate less than 5% were analyzed further by Student's t test. Probe sets that were higher in untreated embryos at P < 0.05 and hence down-regulated by α-amanitin treatment were considered as α-amanitin-sensitive probe sets representing transcripts of embryonic origin in eight-cell embryos.

Effect of NOBOX knockdown on expression of predicted NOBOX-responsive genes at EGA

To determine the effects of NOBOX knockdown on expression of predicted NOBOX-responsive genes at EGA, presumptive zygotes were subjected to NOBOX siRNA microinjection. Uninjected embryos and embryos injected with a negative control scrambled siRNA (universal control no. 1; Ambion) were used as control groups. After microinjection, groups of embryos were cultured in 75- to 90-μl drops of potassium simplex optimization medium (Specialty Media, Phillipsburg, NJ) supplemented with 0.3% BSA, and eight-cell embryos were collected at 52 hpi for real-time PCR analysis of predicted NOBOX-responsive genes (n = 10 embryos per treatment; n = 4 replicates) (see Supplemental Table 1 for the list of primer sequences). oPOSSUM analysis software (http://www.cisreg.ca/cgibin/oPOSSUM/opossum) (23) was used to identify the NOBOX-binding elements (NBEs) in the promoter regions of zygotic transcripts at EGA. A combination of a Z score more than 10, Fisher P value < 0.01, and transcription factor binding score more than 10 was used, which is known to provide minimal likelihood of false-positive results (23).

Effects of NOBOX knockdown on cell allocation to trophectoderm (TE) and inner cell mass (ICM) in bovine blastocyts

To determine the effect of NOBOX depletion on total cell numbers and allocation to TE vs. ICM cells, NOBOX siRNA-injected embryos that reached the blastocyst stage were subjected to differential staining using a previously published procedure (24). The uninjected embryos and negative control siRNA-injected embryos that reached the blastocyst stage were used as controls. At least 10 blastocyts were processed for each treatment, and experiments were replicated four times. A subset of blastocysts from each treatment group were pooled (n = 4 pools of three blastocysts) and subjected to real-time RT-PCR analysis of mRNA abundance for POU5F1/OCT4, ICM marker NANOG, and TE marker CDX2 (see Supplemental Table.1 for the list of primer sequences).

Statistical analysis

For real-time PCR experiments, differences in NOBOX mRNA abundance were analyzed by one-way ANOVA using the general linear models procedure of SAS. For microinjection experiments, rates of embryo development (eight- to 16-cell and blastocyst stages) and blastocyst cell numbers (TE, ICM, and total cell numbers) percent data were subjected to arc-sin transformation before analysis as described above. Differences in treatment means were compared using Fisher's protected least significant difference test. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Results

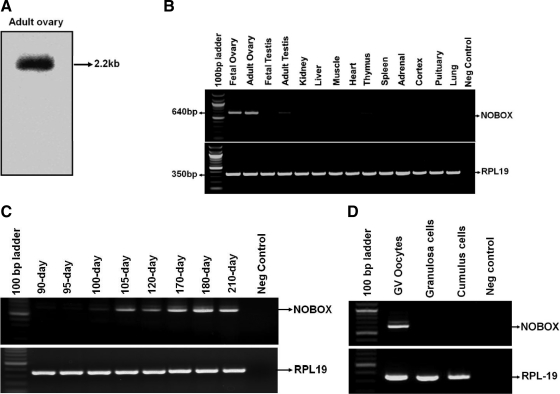

cDNA cloning and genome organization of bovine NOBOX

Using the primers designed based on the predicted bovine NOBOX cDNA sequence, we successfully amplified a cDNA fragment (1500 bp) representing the coding region of bovine NOBOX from bovine fetal ovary cDNA. Northern blot analysis revealed a single transcript of approximately 2.2 kb in bovine adult ovary sample (Fig. 1A). Thus additional 5′- (463 bp) and 3′- (312 bp) sequences were obtained using RACE procedures. The assembled full-length NOBOX cDNA (HQ589330) is 2275 bp containing an open reading frame encoding a protein of 500 amino acids with a conserved homeodomain and typical nuclear localization signal (Supplemental Fig. 1). The predicted NOBOX protein shares 61% and 49% amino acid sequence identity with its human and mouse counterparts, respectively (Supplemental Fig. 2). A basic local alignment tool search of the bovine genome database at National Center for Biotechnology Information revealed that the bovine NOBOX gene is located on chromosome 4, and spans approximately 5.5 kb. Exon and intron boundaries of the genes were determined using the Spidey program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Spidey/). The bovine NOBOX gene has seven exons and six introns as determined by the program (Supplemental Table 2), and all splice sites are in agreement with the consensus sequence (GT-AG rule).

Fig. 1.

Expression of NOBOX mRNA. A, Northern blot analysis of bovine NOBOX transcript. B, Bovine NOBOX mRNA expression in ovary, testis, and 11 somatic tissues determined by RT-PCR analysis. C, RT-PCR analysis of bovine NOBOX mRNA expression in bovine fetal ovaries of different developmental stages. D, Expression of bovine NOBOX mRNA in GV stage oocytes, granulosa cells, and cumulus cells. Bovine RLP19 was used as an internal control.

Tissue distribution of bovine NOBOX mRNA

RT-PCR analysis of RNA samples from a panel of 14 different bovine tissues revealed that expression of NOBOX mRNA is restricted to adult and fetal ovaries with very minor expression in adult testicular samples (Fig. 1B). Analysis of NOBOX mRNA expression in bovine fetal ovaries of different developmental stages showed that the NOBOX mRNA could be detected in fetal ovaries harvested as early as 100 d of gestation (when primary follicles start to form in cows), and is highly abundant in the fetal ovaries of late gestation (Fig. 1C). RT-PCR analysis using RNA isolated from oocytes, granulosa cells, and cumulus cells indicates that bovine NOBOX is expressed in oocytes but not in other follicular somatic cells examined (Fig. 1D).

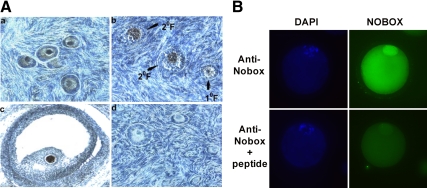

Intraovarian and intraoocyte localization of NOBOX protein

Immunohistochemical localization of NOBOX protein within fetal ovary sections revealed that NOBOX protein is present in oocytes of growing follicles at the primordial (Fig. 2A, panel a; single layer of flattened granulosa cells), primary (Fig. 2A, panel b; single layer of cuboidal granulosa cells), and secondary (Fig. 2A, panel b; multiple layers of cuboidal granulosa cells) through antral follicle stages (Fig. 2A, panel c). Immunoreactivity was not detected in granulosa cells, theca cells, cumulus cells, and control tissue sections incubated in absence of NOBOX antibody (Fig. 2A, panel d). Immunocytochemical analysis of NOBOX protein in GV oocytes using confocal spinning-disk microscopy demonstrated that NOBOX protein is localized in both the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Intraovarian and intraoocyte localization of NOBOX protein. A, Immunohistochemical localization of NOBOX protein in bovine adult ovary. Oocyte-specific localization of NOBOX protein in primordial follicles (panel a), primary follicle (panel b, 1 F), secondary follicle (panel b, 2 F), and antral follicle (panel c) was observed. No staining signal was observed in the oocytes incubated in the absence of NOBOX antibody (panel d). B, Localization of NOBOX protein in GV oocytes by immunocytochemical analysis using confocal spinning-disk microscopy. For negative control, oocytes were incubated with NOBOX antibody preabsorbed with excess antigen (ab41611; Abcam, Cambridge, MA). DAPI, 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole.

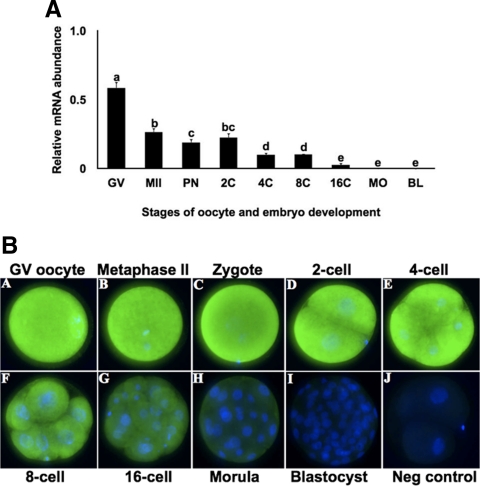

Spatiotemporal expression of bovine NOBOX mRNA and protein during oocyte maturation and early embryonic development

To determine the function of NOBOX during bovine early embryonic development, the temporal expression characteristics of NOBOX in oocytes and early bovine embryos were first investigated. NOBOX mRNA was abundant in GV and MII stage oocytes, as well as pronuclear to eight-cell stage embryos but barely detectable in embryos collected at morula and blastocyst stages (Fig. 3A), suggesting that NOBOX mRNA was maternal in origin. Furthermore, NOBOX mRNA abundance in eight-cell embryos was not diminished by culture in the presence of the transcriptional inhibitor α-amanitin (data not shown). Immunocytochemical analysis demonstrated that NOBOX protein was abundant in GV- and MII-stage oocytes as well as in pronuclear, two-cell and four-cell stage embryos, but immunostaining for the NOBOX protein abundance declined by the eight-cell stage and was barely detectable at morula and blastocyst stages (Fig. 3B). Based on the observed spatiotemporal expression pattern, we hypothesized that NOBOX may have a functional role in bovine early embryonic development.

Fig. 3.

Expression characteristics of bovine NOBOX mRNA and protein during oocyte maturation and early embryonic development. A, Relative abundance of NOBOX mRNA in bovine oocytes and in vitro produced bovine early embryos: GV and MII stage oocytes, pronuclear (PN), two-cell (2C), four-cell (4C), eight-cell (8C), 16-cell (16C), morula (MO), and blastocyst (BL)-stage embryos. Nobox transcript levels were normalized relative to abundance of exogenous control (GFP) RNA and are shown as mean ± sem (n = 4 pools of 10 embryos per treatment). Different letters indicate statistical difference (P < 0.05). B, Immunofluorescent localization of NOBOX protein during oocyte maturation and preimplantation bovine embryos. Nuclear DNA was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Neg, Negative.

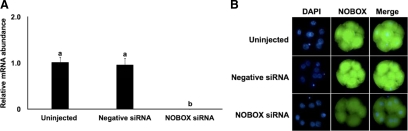

NOBOX is required for bovine early embryonic development

To investigate the function of NOBOX in early embryonic development, we performed RNAi experiments to reduce NOBOX expression in bovine embryos. Four NOBOX siRNA species targeting different regions of the NOBOX transcript were produced in vitro, and initial experiments were performed to test the efficacy and specificity in silencing the NOBOX gene. siRNA 2 and siRNA 3 each resulted in a more than 80% reduction (P < 0.05) in NOBOX mRNA in four-cell embryos relative to uninjected control (Supplemental Fig. 3). Microinjection of a cocktail of NOBOX siRNA 2 and -3 significantly reduced NOBOX mRNA levels in four-cell embryos by more than 95% relative to uninjected and negative control siRNA-injected embryos (Fig. 4A). Microinjection of the siRNA mixture (siRNA 2 and siRNA 3) also dramatically reduced NOBOX immunostaining in eight-cell embryos (Fig. 4B). Further analysis by Western blot also showed reduced NOBOX protein in siRNA-injected embryos (Supplemental Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect of NOBOX siRNA injection in bovine zygotes on expression of NOBOX mRNA and protein in resulting embryos. A, Effect of NOBOX siRNA microinjection on abundance of NOBOX mRNA in four-cell embryos as determined by real-time PCR. Data were normalized relative to abundance of endogenous control ribosomal protein S18 (RSP18) and are shown as mean ± sem (n = 4 pools of 10 embryos per treatment). Different letters indicate statistical difference (P < 0.05). B, Effect of NOBOX siRNA microinjection on abundance of NOBOX protein in eight-cell stage embryos as determined by immunofluorescent staining (n = 4 pools of five to 10 embryos per treatment). Uninjected embryos and embryos injected with a nonspecific siRNA (Neg siRNA) were used as control. Nuclear DNA was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

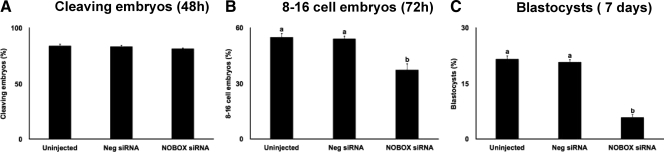

To determine whether knockdown of NOBOX in bovine embryos has any effect on embryonic development, cleavage rate, and proportion of embryos developing to eight- to 16-cell and blastocyst stage for NOBOX siRNA-injected vs. uninjected and negative control siRNA-injected embryos were determined. NOBOX siRNA (siRNA 2 and siRNA 3) injection into bovine zygotes did not affect the cleavage rates (Fig. 5A) but reduced the proportion of embryos developing to eight- to 16-cell stage (Fig. 5B) and blastocyst stage (Fig. 5C) relative to the uninjected and negative control siRNA-injected embryos. These results clearly indicate that knockdown of NOBOX in bovine zygotes impaired development to the blastocyst stage.

Fig. 5.

Effect of RNAi mediated depletion of NOBOX on early embryonic development. A, Proportion of embryos that cleaved within 48 h after fertilization. B, Proportion of embryos developing to eight- to 16-cell stage (determined 72 hpi). C, Proportion of embryos developing to blastocyst stage (determined on d 7). Uninjected embryos and embryos injected with a nonspecific siRNA (Neg siRNA) were used as controls. Data are expressed as mean ± sem from four replicates (n = 25–30 zygotes per treatment per replicate). Values with different letters across treatments indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). Neg, Negative.

NOBOX is essential for induction of specific zygotic transcripts during EGA

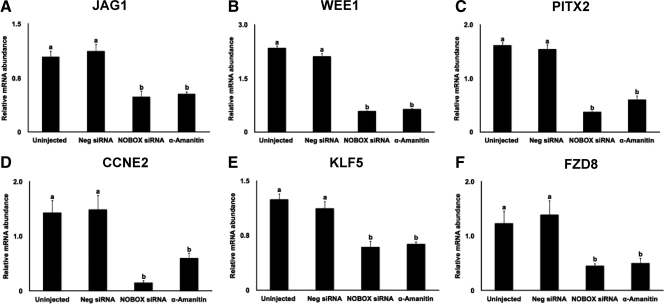

Given the effect on preimplantation development, we tested whether NOBOX regulates expression of zygotic transcripts synthesized during embryogenesis. Microarray analysis of control and α-amanitin-treated embryos collected at the eight-cell stage was used to identify transcripts of embryonic origin induced coincident with EGA (Supplemental Table 3). A total of 198 gene transcripts, which were decreased by 10-fold and greater range in α-amanitin-treated eight-cell stage embryos was selected to identify NBEs in their promoter regions using the oPOSSUM analysis software (http://www.cisreg.ca/cgibin/oPOSSUM/opossum) (23). A total of 21 genes with NBEs that are significantly overrepresented in their promoter regions was identified (Supplemental Table 4). Six such genes (JAG1, WEE1, PITX2, CCNE1, KLF5, and FZD8) were chosen for further examination based on their function and importance during embryogenesis. Interestingly, all six mRNAs were significantly diminished in abundance in NOBOX siRNA-injected embryos collected at the eight-cell stage (Fig. 6, A–F). The expression of these transcripts was also suppressed in the α-amanitin-treated embryos collected at eight-cell stage, confirming they originated from the embryonic genome. Our results suggest that NOBOX either directly or indirectly up-regulates expression of genes from the embryonic genome linked to early development.

Fig. 6.

Knockdown of NOBOX down-regulates the expression of zygotic transcripts (α-amanitin sensitive) in eight-cell stage embryos. Quantitative real-time PCR was used to analyze the expression level of zygotic genes containing NBEs in their promoter regions: JAG1 (A), WEE1 (B), PITX2 (C), CCNE2 (D), KLF5 (E), and FZD8 (F). Data were normalized relative to abundance of endogenous control ribosomal protein S18 (RSP18) and are shown as mean ± sem (n = 4 pools of 10 embryos per treatment). Uninjected embryos and embryos injected with a nonspecific siRNA (Neg siRNA) were used as controls. α-Amanitin-treated embryos were used to confirm the zygotic origin of the transcripts. Different letters indicate statistical difference (P < 0.05). Neg, Negative.

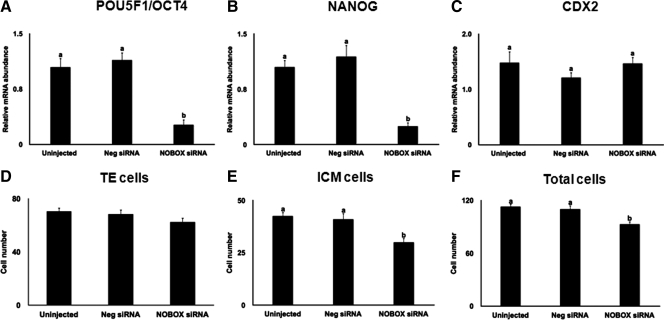

NOBOX regulation of blastocyst cell allocation

NOBOX directly regulates the transcription of Pou5f1/Oct4 in mouse oocytes during folliculogenesis (25). Therefore, we sought to address whether the expression of POU5F1/OCT4 and other genes linked to blastocyst cell allocation (NANOG and CDX2) was affected in the NOBOX siRNA-injected embryos that reached the blastocyst stage. By performing quantitative real-time PCR analysis, we found that the POU5F1/OCT4 and NANOG mRNA expression levels were significantly reduced in the NOBOX siRNA-injected embryos that reached the blastocyst stage compared with the uninjected embryos and negative control siRNA-injected embryos that reached the blastocyst stage (Fig. 7, A and B). No effect of NOBOX siRNA on CDX2 (marker of TE) mRNA abundance in the resulting blastocysts was observed (Fig. 7 C). NOBOX knockdown dramatically reduced the numbers of ICM cells and total cell numbers but did not influence numbers of TE cell in resulting blastocysts (Fig. 7, D–F). Collectively, these results support a functional role for NOBOX in regulating pluripotency genes and cell allocation in bovine blastocysts.

Fig. 7.

Knockdown of NOBOX alters the expression of pluripotency genes and bovine blastocyst cell allocation. Expression of POU5F1/OCT4 (A), NANOG (B), and CDX2 (C) in bovine blastocysts collected on d 7 after insemination. Data were normalized relative to abundance of endogenous control ribosomal protein S18 (RSP18) and are shown as mean ± sem (n = 4 pools of three blastocyst per treatment). Uninjected embryos and embryos injected with a nonspecific siRNA (Neg siRNA) were used as control. Different letters indicate statistical difference (P < 0.05). NOBOX regulation of bovine blastocyst cell allocation (D), number of TE cells (E), number of ICM cells (F), and total cell numbers. Data are expressed as mean ± sem from four replicates (n = 25–30 blastocysts per replicate). Uninjected embryos and embryos injected with a nonspecific siRNA (Neg siRNA) were used as control. Different letters indicate statistical difference (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Our results established a functional role for the oocyte-derived transcription factor NOBOX in regulation of early embryonic development. NOBOX is expressed in a stage-specific manner during early embryonic development, and its depletion in bovine zygotes by siRNA microinjection impaired embryo development to the blastocyst stage. Moreover, knockdown of NOBOX affected the expression of genes from the embryonic genome critical to early development, and expression of pluripotency genes and blastocyst cell allocation were altered in the NOBOX siRNA-injected embryos that reached the blastocyst stage. Previous studies have established an important functional requirement for NOBOX for normal follicular development in mice (11, 12) and women (13, 14) and ovarian expression of specific genes linked to fertility. To our knowledge, a functional role for NOBOX in regulation of early embryonic development has not been reported.

The data for mouse and bovine together thus indicate an important functional requirement of the oocyte transcription factor NOBOX in the regulation of both follicular development and early embryogenesis. However, a requirement of NOBOX for early embryonic development could not be directly ascertained from previous gene-targeting studies in mice. Whereas the contribution of gene-targeting technology to enhanced understanding of oocyte regulation of follicular development and early embryonic development is unquestionable, important functional roles of oocyte-derived gene products in early embryogenesis could, in fact, be undetected in gene-targeting models with an ovarian phenotype due to disruptions in follicular development that preclude development/release of oocytes from null mutant mothers and presence of oocyte-derived RNA and protein for targeted gene in null mutant embryos derived from mothers heterozygous for the mutation. These limitations to the study of the functional role of oocyte-derived factors in early embryogenesis can be overcome by cytoplasmic microinjection of double-stranded RNA into wild-type embryos after fertilization, which can result in specific and effective translational block through later stages of preimplantation embryo development (26–28). The absence of targeted gene product during these developmental stages would reveal important information on gene function and unmask a functional role in early embryogenesis that may not be detectable using conventional gene-targeting strategies. Results of the present studies clearly support a functional role for NOBOX in regulation of multiple aspects of early embryonic development in cattle. For reasons stated above, it is unclear whether the observed role of NOBOX in early embryogenesis is conserved across multiple species, including the mouse, or in fact the role of NOBOX in early embryogenesis is species specific. It is known that EGA occurs later in monoovulatory species, such as cattle and primates including human, compared with the polyovulatory mouse. Thus the maternal-effect genes required to promote initial cleavage divisions and ensure successful early embryonic development in such monotocous species may be distinct from those required in the polytocous mouse model. A species-specific role for the oocyte-specific JY-1 gene in regulation of early embryonic development in cattle has been reported previously (20).

The inability of an embryo to reprogram chromatin and activate transcription of important genes during EGA critical to subsequent development is believed to be the one of the major causes of embryo developmental block in vitro (29, 30) and presumably early embryonic loss in general. Among the early genes that are transcribed at EGA include genes involved in cell cycle progression, transcription regulation, signal transduction, epigenetic modification, transporters, and metabolism (31). However, the specific maternal transcription factors that mediate up-regulation of these early expressed transcripts and proteins during embryonic development are poorly defined. Our results indicate that siRNA-mediated ablation of NOBOX in early embryos blocks induction of key zygotic transcripts at EGA linked to transcriptional (KLF5, PITX2) (32, 33), cell cycle (WEE1, CCNE2) (34, 35), and signaling functions (JAG1, FZD8) (36, 37) during embryogenesis. Hence, the reduced development of NOBOX-depleted embryos to the blastocyst stage may be attributed to defects in EGA and absence of expression of specific zygotic transcripts critical to development.

The first cell lineage allocation event in mammalian embryogenesis occurs at compaction in mouse embryos and results in the formation of the ICM and TE lineages in the blastocyst (38). Multiple lines of evidence indicate the transcription factor Oct4 is essential for the control of early lineage development (39) and the level of Oct4 is crucial for determining the development of distinct cell fates of embryonic stem (ES) cells. Artificial repression of Pou5f1/Oct4 in ES cells induces differentiation of the TE lineage; but when Pou5f1/Oct4 is overexpressed ES cells differentiate mainly into primitive endoderm-like cells (40). In addition, only 1.5-fold-elevated expression of Pou5f1/Oct4 in germ cells leads to development of gonadal tumors (41), and loss of Pou5f1/Oct4 in germ cells results in apoptosis (42). Furthermore, morpholino-mediated depletion of Pou5f1/Oct4 in one- to two-cell stage mouse embryos affected embryonic development before the blastocyst stage (43). Interestingly, such studies also reported that Pou5f1/Oct4 plays a critical role in reprogramming the early embryo during the maternal-to-embryonic transition by regulating genes that encode for transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulators (43). Therefore, Pou5f1/Oct4 expression must be strictly controlled in a developmental stage- and cell type-specific manner. However, the precise mechanism and the number of transcription factors involved in the regulation of POU5F1/OCT4 levels in vivo during development are not well understood. Recently, several factors have been identified, such as NANOG (44), SOX2 (45), FOXD3 (44), and SALL4 (46), that are critical in modulating ES cell pluripotency and early embryonic development via transcriptional regulation of POU5F1/OCT4. Results of the present studies demonstrated that ablation of NOBOX in early embryos significantly reduced the zygotic transcription of POU5F1/OCT4 in embryos that reached the blastocyst stage, indicating that NOBOX is also a key regulator of POU5F1/OCT4 expression during early embryonic development. NOBOX binding and transactivation of the mouse Pou5f1/Oct4 promoter have been previously reported (25).

Ablation of NOBOX in early embryos also impacted cell lineage determination in embryos that reached the blastocyst stage resulting in reduced total cell numbers and numbers of ICM cells. Effects of NOBOX depletion on cell allocation in embryos reaching the blastocyst stage may be directly linked to reduced expression of POU5F1/OCT4. Previous studies demonstrated that POU5F1/OCT4 knockdown in bovine zygotes resulted in reduced numbers of ICM cells in resulting blastocysts (48). Reduced expression of NANOG mRNA in blastocysts derived from NOBOX siRNA-injected embryos was also observed in the present studies. Previous studies reported that POU5F1/OCT4 is required for the transcriptional regulation of Nanog, because knockdown of Pou5f1/Oct4 through RNAi in mouse ES cells significantly reduced Nanog promoter activity (49). Hence, the decreased expression of NANOG mRNA and reduced number of ICM cells might also be directly attributed to down-regulation of POU5F1/OCT4 expression in NOBOX-depleted embryos.

No effect of NOBOX ablation on numbers of TE cells or expression of the TE-specific transcription factor CDX2 mRNA was observed in the present studies, supporting specific effects of NOBOX ablation on the ICM lineage. In contrast, Pou5f1/Oct4 regulation of Cdx2 and the TE lineage has been reported previously in the mouse model. Suppression of Pou5f1/Oct4 mRNA in mouse ES cells caused induction of characteristics of trophectodermal differentiation and an increase in expression of the trophoblast-specific factor CDX2 (50, 51). More recent studies have described the function of maternally and zygotically provided CDX2 in maintaining appropriate polarization of blastomeres at the eight- and 16-cell stage and TE lineage-specific differentiation during early development of the mouse embryo (52). More detailed analysis will be required to determine the specific mechanisms responsible for reduced numbers of ICM, but not TE cells, in blastocysts derived from NOBOX-depleted embryos and the specific role of oocyte-derived NOBOX in regulatory networks in embryo-derived pluripotent stem cells.

In summary, results of the present studies establish a novel functional role for NOBOX during early embryonic development in the bovine model. Results support an important requirement of NOBOX for embryonic development to the blastocyst stage and blastocyst cell allocation and suggest that NOBOX mediates up-regulation of specific zygotic transcripts at EGA critical to subsequent development. Results also provide critical new information regarding the spatiotemporal expression of NOBOX during oocyte and early embryonic development. In the unique developmental context of the maternal-embryonic transition, accompanied by deadenylation and degradation of maternal transcripts, it will be interesting to determine the posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms that mediate observed temporal changes in NOBOX mRNA and protein in early embryos and the functional significance of this expression pattern characteristic of other maternal effect genes critical to early embryogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jason Knott and Dr. Jason B. Cibelli (Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI) for graciously supporting our microscopy work.

This work was supported by National Research Initiative Competitive Grant 2008-35203-19094 from the US Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture (to G.W.S.), Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant 2009-65203-05706 from the US Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture (to J.Y.), National Institutes of Health Grant RR15253 (to K.L.), and funds from the West Virginia Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station (Hatch project no. 427). The study is published with the approval of the station director as scientific paper No. 3085.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- EGA

- Embryonic genome activation

- ES

- embryonic stem

- GV

- germinal vesicle

- hpi

- hours post insemination

- ICM

- inner cell mass

- NBE

- NOBOX-binding element

- NOBOX

- newborn ovary homeobox

- RACE

- rapid amplification of cDNA ends

- RNAi

- RNA interference

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- TE

- trophectoderm.

References

- 1. Amleh A, Dean J. 2002. Mouse genetics provides insight into folliculogenesis, fertilization and early embryonic development. Hum Reprod Update 8:395–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. De Sousa PA, Watson AJ, Schultz GA, Bilodeau-Goeseels S. 1998. Oogenetic and zygotic gene expression directing early bovine embryogenesis: a review. Mol Reprod Dev 51:112–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Soyal SM, Amleh A, Dean J. 2000. FIGalpha, a germ cell-specific transcription factor required for ovarian follicle formation. Development 127:4645–4654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liang L, Soyal SM, Dean J. 1997. FIGα, a germ cell specific transcription factor involved in the coordinate expression of the zona pellucida genes. Development 124:4939–4947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tong ZB, Gold L, Pfeifer KE, Dorward H, Lee E, Bondy CA, Dean J, Nelson LM. 2000. Mater, a maternal effect gene required for early embryonic development in mice. Nat Genet 26:267–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu X, Viveiros MM, Eppig JJ, Bai Y, Fitzpatrick SL, Matzuk MM. 2003. Zygote arrest 1 (Zar1) is a novel maternal-effect gene critical for the oocyte-to-embryo transition. Nat Genet 33:187–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burns KH, Viveiros MM, Ren Y, Wang P, DeMayo FJ, Frail DE, Eppig JJ, Matzuk MM. 2003. Roles of NPM2 in chromatin and nucleolar organization in oocytes and embryos. Science 300:633–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zheng P, Dean J. 2009. Role of Filia, a maternal effect gene, in maintaining euploidy during cleavage-stage mouse embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:7473–7478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bettegowda A, Lee KB, Smith GW. 2008. Cytoplasmic and nuclear determinants of the maternal-to-embryonic transition. Reprod Fertil Dev 20:45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Suzumori N, Yan C, Matzuk MM, Rajkovic A. 2002. Nobox is a homeobox-encoding gene preferentially expressed in primordial and growing oocytes. Mech Dev 111:137–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rajkovic A, Pangas SA, Ballow D, Suzumori N, Matzuk MM. 2004. NOBOX deficiency disrupts early folliculogenesis and oocyte-specific gene expression. Science 305:1157–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Choi Y, Qin Y, Berger MF, Ballow DJ, Bulyk ML, Rajkovic A. 2007. Microarray analyses of newborn mouse ovaries lacking Nobox. Biol Reprod 77:312–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Qin Y, Choi Y, Zhao H, Simpson JL, Chen ZJ, Rajkovic A. 2007. NOBOX homeobox mutation causes premature ovarian failure. Am J Hum Genet 81:576–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Qin Y, Shi Y, Zhao Y, Carson SA, Simpson JL, Chen ZJ. 2009. Mutation analysis of NOBOX homeodomain in Chinese women with premature ovarian failure. Fertil Steril 91:1507–1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Richardson C, Jones PC, Barnard V, Hebert CN, Terlecki S, Wijeratne WV. 1990. Estimation of the developmental age of the bovine fetus and newborn calf. Vet Rec 126:279–284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Murdoch WJ, Dailey RA, Inskeep EK. 1981. Preovulatory changes prostaglandins E2 and F2 α in ovine follicles. J Anim Sci 53:192–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bettegowda A, Patel OV, Lee KB, Park KE, Salem M, Yao J, Ireland JJ, Smith GW. 2008. Identification of novel bovine cumulus cell molecular markers predictive of oocyte competence: functional and diagnostic implications. Biol Reprod 79:301–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tejomurtula J, Lee KB, Tripurani SK, Smith GW, Yao J. 2009. Role of importin α8, a new member of the importin α family of nuclear transport proteins, in early embryonic development in cattle. Biol Reprod 81:333–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bettegowda A, Patel OV, Ireland JJ, Smith GW. 2006. Quantitative analysis of messenger RNA abundance for ribosomal protein L-15, cyclophilin-A, phosphoglycerokinase, β-glucuronidase, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, β-actin, and histone H2A during bovine oocyte maturation and early embryogenesis in vitro. Mol Reprod Dev 73:267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bettegowda A, Yao J, Sen A, Li Q, Lee KB, Kobayashi Y, Patel OV, Coussens PM, Ireland JJ, Smith GW. 2007. JY-1, an oocyte-specific gene, regulates granulosa cell function and early embryonic development in cattle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:17602–17607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee KB, Bettegowda A, Wee G, Ireland JJ, Smith GW. 2009. Molecular determinants of oocyte competence: potential functional role for maternal (oocyte-derived) follistatin in promoting bovine early embryogenesis. Endocrinology 150:2463–2471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Silva CC, Groome NP, Knight PG. 2003. Immunohistochemical localization of inhibin/activin α, β(A) and β(B) subunits and follistatin in bovine oocytes during in vitro maturation and fertilization. Reproduction 125:33–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ho Sui SJ, Fulton DL, Arenillas DJ, Kwon AT, Wasserman WW. 2007. oPOSSUM: integrated tools for analysis of regulatory motif over-representation. Nucleic Acids Res 35:W245–W252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Machaty Z, Day B, Prather R. 1998. Development of early porcine embryos in vitro and in vivo. Biol Reprod 59:451–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Choi Y, Rajkovic A. 2006. Characterization of NOBOX DNA binding specificity and its regulation of Gdf9 and Pou5f1 promoters. J Biol Chem 281:35747–35756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wianny F, Zernicka-Goetz M. 2000. Specific interference with gene function by double-stranded RNA in early mouse development. Nat Cell Biol 2:70–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Paradis F, Vigneault C, Robert C, Sirard MA. 2005. RNA interference as a tool to study gene function in bovine oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev 70:111–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schellander K, Hoelker M, Tesfaye D. 2007. Selective degradation of transcripts in mammalian oocytes and embryos. Theriogenology 68(Suppl 1):S107–S115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Betts DH, King WA. 2001. Genetic regulation of embryo death and senescence. Theriogenology 55:171–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sirard MA, Richard F, Blondin P, Robert C. 2006. Contribution of the oocyte to embryo quality. Theriogenology 65:126–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Misirlioglu M, Page GP, Sagirkaya H, Kaya A, Parrish JJ, First NL, Memili E. 2006. Dynamics of global transcriptome in bovine matured oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:18905–18910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rodríguez-León J, Rodríguez Esteban C, Martí M, Santiago-Josefat B, Dubova I, Rubiralta X, Izpisúa Belmonte JC. 2008. Pitx2 regulates gonad morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:11242–11247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Parisi S, Passaro F, Aloia L, Manabe I, Nagai R, Pastore L, Russo T. 2008. Klf5 is involved in self-renewal of mouse embryonic stem cells. J Cell Sci 121:2629–2634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tominaga Y, Li C, Wang RH, Deng CX. 2006. Murine Wee1 plays a critical role in cell cycle regulation and pre-implantation stages of embryonic development. Int J Biol Sci 2:161–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gotoh T, Shigemoto N, Kishimoto T. 2007. Cyclin E2 is required for embryogenesis in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol 310:341–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Deardorff MA, Tan C, Conrad LJ, Klein PS. 1998. Frizzled-8 is expressed in the Spemann organizer and plays a role in early morphogenesis. Development 125:2687–2700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Xue Y, Gao X, Lindsell CE, Norton CR, Chang B, Hicks C, Gendron-Maguire M, Rand EB, Weinmaster G, Gridley T. 1999. Embryonic lethality and vascular defects in mice lacking the Notch ligand JAGGED1. Hum Mol Genet 8:723–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rossant J, Tam PPL. 2009. Blastocyst lineage formation, early embryonic asymmetries and axis patterning in the mouse. Development 136:701–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pei D. 2009. Regulation of pluripotency and reprogramming by transcription factors. J Biol Chem 284:3365–3369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Niwa H, Miyazaki J, Smith AG. 2000. Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat Genet 24:372–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gidekel S, Pizov G, Bergman Y, Pikarsky E. 2003. Oct-3/4 is a dose-dependent oncogenic fate determinant. Cancer Cell 4:361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kehler J, Tolkunova E, Koschorz B, Pesce M, Gentile L, Boiani M, Lomelí H, Nagy A, McLaughlin KJ, Schöler HR, Tomilin A. 2004. Oct4 is required for primordial germ cell survival. EMBO Rep 5:1078–1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Foygel K, Choi B, Jun S, Leong DE, Lee A, Wong CC, Zuo E, Eckart M, Reijo Pera RA, Wong WH, Yao MWM. 2008. A novel and critical role for Oct4 as a regulator of the maternal-embryonic transition. PLoS ONE 3:e4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pan G, Li J, Zhou Y, Zheng H, Pei D. 2006. A negative feedback loop of transcription factors that controls stem cell pluripotency and self-renewal. FASEB J 20:1730–1732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chew JL, Loh YH, Zhang W, Chen X, Tam WL, Yeap LS, Li P, Ang YS, Lim B, Robson P, Ng HH. 2005. Reciprocal transcriptional regulation of Pou5f1 and Sox2 via the Oct4/Sox2 complex in embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol 25:6031–6046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang J, Tam WL, Tong GQ, Wu Q, Chan HY, Soh BS, Lou Y, Yang J, Ma Y, Chai L, Ng HH, Lufkin T, Robson P, Lim B. 2006. Sall4 modulates embryonic stem cell pluripotency and early embryonic development by the transcriptional regulation of Pou5f1. Nat Cell Biol 8:1114–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nordhoff V, Hübner K, Bauer A, Orlova I, Malapetsa A, Schöler HR. 2001. Comparative analysis of human, bovine, and murine Oct-4 upstream promoter sequences. Mamm Genome 12:309–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nganvongpanit K, Müller H, Rings F, Hoelker M, Jennen D, Tholen E, Havlicek V, Besenfelder U, Schellander K, Tesfaye D. 2006. Selective degradation of maternal and embryonic transcripts in in vitro produced bovine oocytes and embryos using sequence specific double-stranded RNA. Reproduction 131:861–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rodda DJ, Chew JL, Lim LH, Loh YH, Wang B, Ng HH, Robson P. 2005. Transcriptional regulation of nanog by OCT4 and SOX2. J Biol Chem 280:24731–24737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Velkey JM, O'Shea KS. 2003. Oct4 RNA interference induces trophectoderm differentiation in mouse embryonic stem cells. Genesis 37:18–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hay DC, Sutherland L, Clark J, Burdon T. 2004. Oct-4 knockdown induces similar patterns of endoderm and trophoblast differentiation markers in human and mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 22:225–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jedrusik A, Bruce AW, Tan MH, Leong DE, Skamagki M, Yao M, Zernicka-Goetz M. 2010. Maternally and zygotically provided Cdx2 have novel and critical roles for early development of the mouse embryo. Dev Biol 344:66–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]