Abstract

We have developed a new expression vector, pcIts ind+, based upon the powerful rightward promoter of bacteriophage lambda, which is controlled by a temperature-sensitive and chemically-inducible version of the lambda repressor on the same plasmid. Locating the repressor gene on the plasmid makes this vector “portable” in that it can be used to transform any strain of E. coli. Hence, control over strains, induction conditions, and harvest times can be used to optimize yields of heterologous proteins. To provide a proof of concept, we show that Escherichia coli recA+ and recA− host cells transformed with pcIts ind+ modKlenTaq1 (a modified version of the large fragment of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase I) could be grown to high cell densities in multiple shake-flasks. A mutant version of modKlenTaq1 (V649C) could be induced by simply raising the thermostat setting from 30 to 37 °C and (in the case of recA+ cells) adding nalidixic acid to achieve full induction (12 to 13% of the total cellular protein). Using a rapid, two-step purification process, it was possible to purify nearly 300 mg of modKlenTaq1 V649C from six 2.8-liter baffle-bottomed shake-flasks each holding 1.5 liters of culture for a final yield of approximately 33 mg per liter or 3 mg of purified enzyme per gram of cells wet weight.

Keywords: KlenTaq, over-expression, heat-treated, heat stable, lambda promoter

Introduction

Enzyme structure and function studies require increasingly large amounts of pure enzymes. For example, to crystallize more complicated structures such as a DNA polymerase in a ternary complex with DNA plus an in-coming nucleotide, 100 milligram quantities of the enzyme are necessary to define and to optimize crystallization strategies. In addition, transient kinetic methods used to measure individual steps in an enzyme reaction pathway require that the enzyme be present in reagent concentrations [1]. It has become common practice for research enzymology labs to use recombinant DNA technology to produce the required amounts of enzymes typically using Escherichia coli (E. coli) because this organism is inexpensive and easy to culture in shake-flasks. Hence, over the course of the past two decades much attention has been focused on strong promoter systems and commercially available expression vectors [2] to improve heterologous gene expression in this host. High yields have been reported for many enzymes but this usually has meant a high yield per cell in relatively low cell density cultures. Overall enzyme yields have been typically only a few milligrams of purified protein per liter of culture. The production of hundred milligram quantities usually requires technology, such as stirred fermenters with nutrient feeding capabilities that are unavailable to the average enzymology laboratory. Even in industry where large fermenters are available, there is often a backlog in protein purification that limits productivity.

Existing expression vector systems based upon the strong phage promoters from bacteriophage lambda have been widely used for high specific cell yields of recombinant products. These vectors are typically controlled by a temperature sensitive and RecA cleavage-resistant form of the lambda repressor gene, λcI857, that has been located either in the host chromosome, or on an accessory plasmid, or on-board the expression vector, itself [3]. While popular, cI857-controlled expression vectors can only be induced by a temperature shock, typically, a rapid temperature increase from a non-permissive 32 °C to 42 °C to inactivate the repressor. Rapid temperature jumps are difficult to accomplish in multi-liter, multi-vessel, shaker-incubators.

We have designed an expression vector with several key characteristics in addition to high specific cell yield: 1) chemical and/or temperature induction; 2) moderate to high cell density capability in shake-flasks; and, 3) host strain “portability,” including recA+ hosts. This vector is based upon the powerful rightward promoter from bacteriophage lambda cloned into a high copy-number plasmid, pUC19 [4]. This promoter/copy-number combination ensures high levels of transcription per cell following induction [5]. The promoter/gene transcriptional unit is separated from the plasmid origin of replication by the T1T2 transcription terminators from the rrnB operon of E. coli [6] thus preventing post-induction transcription from interfering with plasmid replication and stability. Furthermore, transcription is controlled by a lambda repressor “on-board” the plasmid thus making it possible to rapidly screen a variety of host strains to optimize expression yields, stability, and solubility of recombinant products. This repressor makes it possible to use either chemical or temperature induction or both. In this report, we describe using the plasmid, pcIts ind+, to express a mutant version of the large fragment of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase I, as a test enzyme, using all three modes of induction: chemical alone, temperature shock, and chemical plus temperature shift. Cultures grown in shake-flasks routinely achieved final cell densities of 9 to 12 A600 and yielded purified polymerase in the range of 30 to 35 mg/liter of culture, or 300 mg per 9 liter batch. Thus, our optimized expression yielded amounts of purified protein usually attainable only in large-scale fermenters.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Bacteriophage lambda DNA, λcI857 ind 1 Sam7, pUC19 DNA, chemically competent E. coli C2984H cells (K12 F′ proA+B+ lacIq Δ lacZM15/fhu2A Δ (lac-proAB) glnV zgb-210::Tn10(TetR) endA1 thi-1 Δ (hsdS-mcrB)5 recA+), and all restriction enzymes were obtained from New England Biolabs. Chemically competent NovaBlue (endA1 hsdR17(rK12-mK12+) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac[F−proA+B+ lacIq ZDM15::Tn10(tetR)] and DH5α (Δ(arg-lac)169 f80ΔlacZ58(M15) glnV44(AS) l- rfbC1 gyrA96(NalR) recA1 endA1 spoT1 thi-1 hsdR17) chemically competent E. coli cells were purchased from Strategene. Thermus aquaticus YT-1 lyophilized cells (ATCC #25104) were obtained from the ATCC. Chromosomal DNA was isolated using the Genomic DNA Purification Protocol and columns from Qiagen Inc. according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Stoffel Fragment of Taq DNA polymerase, a modified form 544 amino acids long lacking the N-terminal 289 amino acids, was purchased from Applied Biosystems.

Culture Media

Transformed E. coli cells were grown in TBS medium [7] or on LB plates [8] at temperatures indicated in the text. Ampicillin (100 μg/ml) was added when necessary as indicated. Thermus aquaticus YT-1 cells were grown in Castenholtz 1% TYE plus vitamins and salts as described in the ATCC literature (recipe #461) with gentle shaking at 70 °C [9].

Cloning Thermus aquaticus DNA Polymerase I

The chromosomal DNA region spanning the DNA polymerase gene, Taq DNAP I, of Thermus aquaticus was isolated by PCR amplification using the DNAP I primers as shown in Table I and purified chromosomal DNA as template. The amplicon was cut with Bgl2 plus Sph1 and subcloned into pUC19. The modified KlenTaq (“modKlenTaq1”) version of this polymerase gene was constructed by PCR amplification of the catalytic domain region using the modKlenTaq and DNAP I Reverse Primers also shown in Table I. The forward primer adds an Nde1 site at the start of the coding region for the truncated version of the Taq DNAP1 gene which encodes the C-terminal amino acids 281–832. The forward primer also adds 7 additional amino acids at the N-terminal end of the coding region for improved solubility, MGKRKST [10]. A single amino acid substitution mutant, V649C (numbering referring to the full-length enzyme), was constructed using PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. Taq DNA polymerase does not contain any naturally occurring cysteines. Hence, this mutation which generates a surface exposed cysteine residue provides a unique labeling site for fluorescent dyes without affecting enzyme activity [11].

Table 1.

Oligodeoxynucleotide Primers

| DNAP I Forward Primer | gcatcagaagctcAGATCTacctgcctgag |

| DNAP I Reverse Primer | cagcaataGCATGCtcactccttggcggagagcca |

| mod-KlenTaq Primer | cgatgaCATATGggtaaacgtaaatctactgcctttctggagaggct |

| lambda 37151 | agctctaaGGCGGCggagtgaaaattcccctaattcgatgaagattct |

| lambda 38039 | ttgatacCATATG aacctccttagtacatgcaaccatt |

Table 1 lists the primers used to construct and modify the expression plasmid, pcIts ind+ modKlenTaq1. Primers that have “cryptic” restriction sites to facilitate insertions are shown in CAPS. Underlined bases represent portions of coding regions for the genes indicated.

The reverse primer adds an Sph1 site immediately adjacent to the stop codon. This amplicon was cut with Nde1 and Sph1 and subcloned into a modified pUC19 vector containing the T1T2 transcription terminator region from the rrnB operon of E. coli. The terminators are located between the multi-cloning site and the origin of replication region in the plasmid. This formed the “base” plasmid used to construct the final expression vector as described below.

Expression Vector Construction

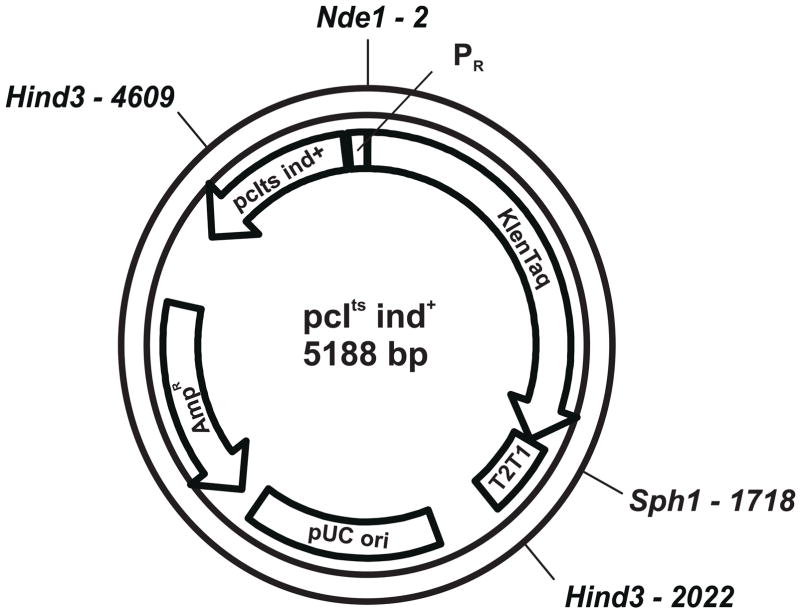

The region of the lambda genome containing the repressor gene, cI857 ind 1, and the rightward promoter, λPR, was isolated as a PCR amplicon spanning bases λ37151–λ38039 using the primers shown in Table I and purified lambda DNA as template. The reverse primer (λ37151) was designed to generate an Nde1 site at the original start codon for the λcro gene (“CATATG”). The forward primer (λ38039) was designed to add a Kas1 site 3′ to the λcI857 ind 1 gene. However, Kas1 digests of the amplicon generated a shorter than expected fragment suggesting additional cutting for unknown reasons within the coding region of the repressor gene. Therefore, the amplicon was cut with Mfe1 (originally at λ37186, downstream from the repressor gene) plus Nde1 and subcloned into the pUC19-T1T2 “base” plasmid described above that was cut with EcoR1 and Nde1 generating pcI857ts ind1-mKlenTaq1. The lambda repressor ind 1 mutation originally at position λ37589 was “back-mutated” to the wild-type sequence from T to C (with subsequent loss of the Hind3 site originally at λ37584) using site-directed mutagenesis forming the expression plasmid, pcIts ind+ modKlenTaqI as shown in Figure 1. This plasmid or the mutant version, V649C, were used for all expression testing.

Figure 1. Partial Restriction Site Map for pcIts ind+ modKlenTaqI.

The diagram shows the restriction sites used for insertion of the modified KlenTaq I gene, KlenTaq, as well as transcription terminators, T1T2; the β-lactamase gene, AMPR; the lambda repressor, pcIts ind+; and, the rightward promoter from bacteriophage lambda, PR. The map shows that there is only one Hind3 site (equivalent to λ37459, lambda genome numbering) in the repressor gene because the ind 1 to ind+ “back-mutation” eliminates the second site (equivalent to λ37589, T to C).

Expression Testing

The plasmid, pcIts ind+ modKlenTaqI, was transformed into chemically competent cells, spread onto LB plus ampicillin plates, and incubated at 30 °C. Ampicillin resistant colonies were selected and used to inoculate cultures to test expression, typically, 75 to 100 ml TBS in 500-ml baffle-bottomed erlenmeyer flasks shaken at 150 rpm at 30 or 32 °C, unless noted otherwise. When the cultures reached a cell density of 4 A600, the cells were induced by one of three methods: 1) Chemical Induction Alone, addition of nalidixic acid to 50 μg/ml; 2) Temperature Shock, the temperature was rapidly raised to 42 °C by swirling in a water bath and maintained at 42 °C for 20 minutes after which incubation was continued at 37 °C; or Both Chemical and Temperature Shift Induction, nalidixic acid was added to the culture and the temperature setting on the incubator shaker was simply reset to 37 °C with out the 42 °C heat shock step.

Gel Samples

At the times indicated in the figures, samples were removed from the cultures and placed on ice. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 6000 × g for 5 minutes at room temperature. Cell pellets were resuspended in Lysis Buffer (50 mM TRIS, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8) plus lysozyme (0.5 mg/ml) and incubated at 37 °C for 10 minutes. Sodium chloride was added to the lysate to a final concentration of 500 mM to prevent the polymerase from binding to DNA in the pellets. After briefly sonicating the lysate to reduce viscosity, an aliquot was removed as the Total Cell Protein Sample. The remainder of the lysate was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 minutes at room temperature and an aliquot was removed from the supernatant to represent the Soluble Protein Sample. The remainder of the supernatant was heat treated at 80 °C for 45 minutes and an aliquot was taken from as the Heat-treated Protein Sample after cooling. The pellet from this centrifugation step was resuspended and represented the Insoluble Material sample. Protein samples were analyzed by 8% SDS-PAGE [12]. Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay (BioRad, Richmond, CA).

Large-scale Cultures for modKlenTaq1 V649C

Six 2.8-liter baffle-bottomed Fernbach flasks (Bellco BioTech) each containing 1.5-liters of TBS plus ampicillin were used to grow C2984H cells transformed with pcIts ind+ modKlenTaqI V649C at 30 °C with shaking at 150 rpm. When the cultures reached cell densities above 3 A600, the cells were induced by Chemical + Temperature Shift by adding nalidixic acid to a final concentration of 50 mg/liter and raising the shaker incubator temperature setting to 37 °C. Pre-induction and Harvest Samples were removed and processed as described above for SDS-PAGE. The cells were harvested at 22 to 26 hours post inoculation by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4 °C. Cell pellets were weighed and stored at −20 °C.

Purification

Frozen cell pastes were resuspended on ice in 5 volumes of Lysis Buffer (50 mM TRIS, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 50 μM PMSF, pH 8) and lysozyme was added to 0.15 mg/ml. After 30 minutes on ice with stirring, the lysate was sonicated to reduce viscosity. Sodium chloride was added to a final concentration of 0.25 M, and the solution was slowly added with constant stirring to an equal volume of Lysis Buffer in a water bath at 80 °C. The temperature of the mixture was never allowed to drop below 60 °C during additions. After all of the lysate was added, the mixture was incubated at 80 °C with stirring for an additional 45 minutes to precipitate host proteins. The heat treated lysate was cooled on ice and 10% polyethyleneimine was added drop-wise with stirring to a final concentration of 0.3%.

After 30 minutes, cell debris and denatured proteins were pelleted at 10,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatant was diluted 3-fold with Column Buffer (20 mM TRIS, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% TWEEN-20, 1% glycerol, pH 8.0) to reduce the salt concentration and loaded onto tandem BioRex-70 (2.6 × 20 cm) and Heparin-Sepharose (2.6 × 15 cm) columns. After washing with Column Buffer plus 100 mM NaCl until the A280 returned to background, the enzyme was eluted from the Heparin-Sepharose column using a 5.5 CV linear gradient (100 to 1000 mM NaCl). The major peak eluting from the affinity column was modKlenTaq1. Each fraction was 14 ml. Aliquots from the fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE as indicated in the Figures. Peak fractions were pooled and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

Activity Measurements

The activities for purified samples of modKlenTaq1 V649C were determined by PCR titration experiments [13] using commercially available Stoffel Fragment of Taq DNA polymerase as a standard. PCR conditions were as suggested by the manufacturer using as template, the groEL/S operon from E. coli in pBB528 [14] with forward-primer 5′-CAATTTCACACAGAATTCATTAAAGAGGAGAAATTAACCATGAA and reverse primer 5′-TCAGCTAATTAAGCTTACATCATGCCGCCCA. The band intensities of the amplicons on the same gel were used to compare the activity of various dilutions of purified enzyme samples.

Results

Expression Plasmid Construction and Testing

The segment of the lamdba genome spanning the λcI repressor, λOR and λPR region is of special interest for the design and construction of expression plasmids because it can serve as a “self-contained” transcriptional/translational control unit. The lambda repressor is capable of very tight control over transcription from the rightward promoter and with the repressor gene on-board the plasmid, this vector is not limited to repressor expressing host strains. A segment of the lambda genome from λ37187 to λ38043 was amplified using PCR primers containing cryptic restriction sites as shown in Table I. By changing the bases just before the start codon of the λcro gene, a unique Nde1 site was introduced that could be used for the insertion of heterologous coding sequences. Figure 1 shows a partial restriction map for the plasmid, pcIts ind+ modKlenTaq1.

The λcI857 ind 1 repressor originally had two Hind3 restriction sites at positions λ37584 and λ37459 (numbering refers to the lambda genome sequence, GenBank accession number NC_001416). The former site contains the ind 1 mutation that renders the repressor resistant to cleavage by RecA protein. Using site-directed mutagenesis, the final T of the Hind3 site spanning the ind 1 mutation was changed to a C eliminating this restriction site which could be used to screen recombinants. This “back-mutation” of ind 1 to wild-type allows plasmid borne expression to be induced through the simple addition of nalidixic acid to the cultures. Nalidixic acid is a DNA gyrase inhibitor that blocks DNA synthesis which induces an SOS response [15]. One of the genes induced during an SOS response is recA. The RecA protein specifically cleaves the wild-type (ind+) lambda repressor.

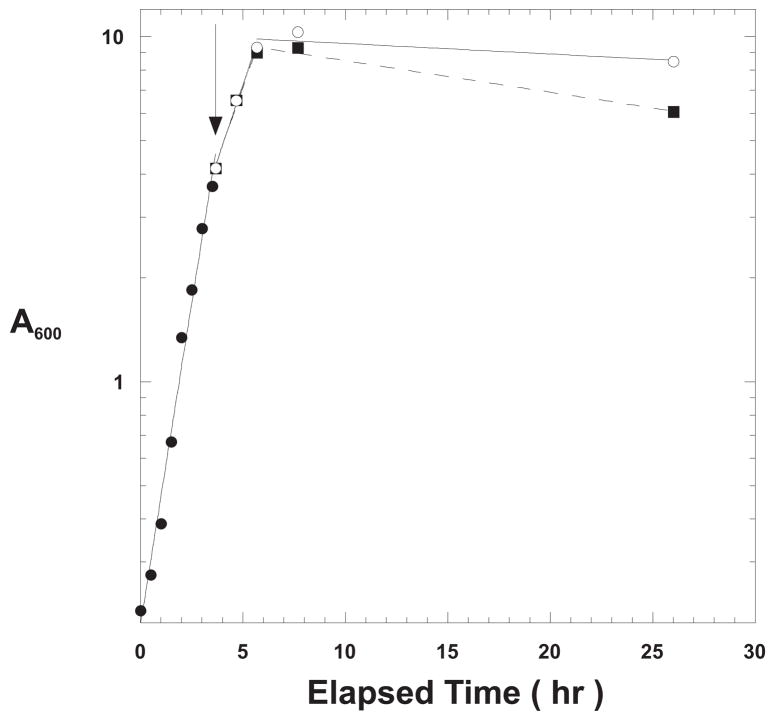

The unique Nde1 and Sph1 sites in the vector were used to insert a segment of the Thermus aquaticus chromosome encoding a portion of Taq DNA polymerase 1, “modKlenTaq1.” C2984H cells transformed with pcIts ind+ modKlenTaq1 were used to test different modes of induction as shown in Figure 2. A 500-ml baffle-bottomed Erlenmeyer flask containing 225 ml of TBS plus ampicillin was inoculated from an overnight culture of C2984K[pcIts ind+ modKlenTaq1] and incubated at 32 °C with shaking at 150 rpm. When the cell density reached 4 A600, a Pre-induction Sample was removed and held on ice while the remainder of the culture was split into two subcultures, 100 ml each: 1) Chemical Induction Alone; and, 2) Temperature Shock. In the case of the Chemical Induction Alone culture, nalidixic acid was added to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml and incubation was continued at 32 °C. The Temperature Shock culture was transferred to a 42 °C water bath, swirled for 20 minutes and then incubated at 37 °C with shaking for the duration of the experiment. This temperature induction regimen is the “classical” temperature induction method used for lambda promoter-based expression plasmids under the control of a temperature-sensitive lambda repressors [3]. The cultures showed very similar growth curves; although, the growth rate for the nalidixic acid treated culture lagged behind the temperature induced culture as shown in Figure 2. This may have been due to the different incubation temperatures following induction or more likely, due to induction of the SOS response. The concentration of nalidixic acid used in these induction tests was sufficiently high to eventually inhibit all chromosomal DNA replication [16].

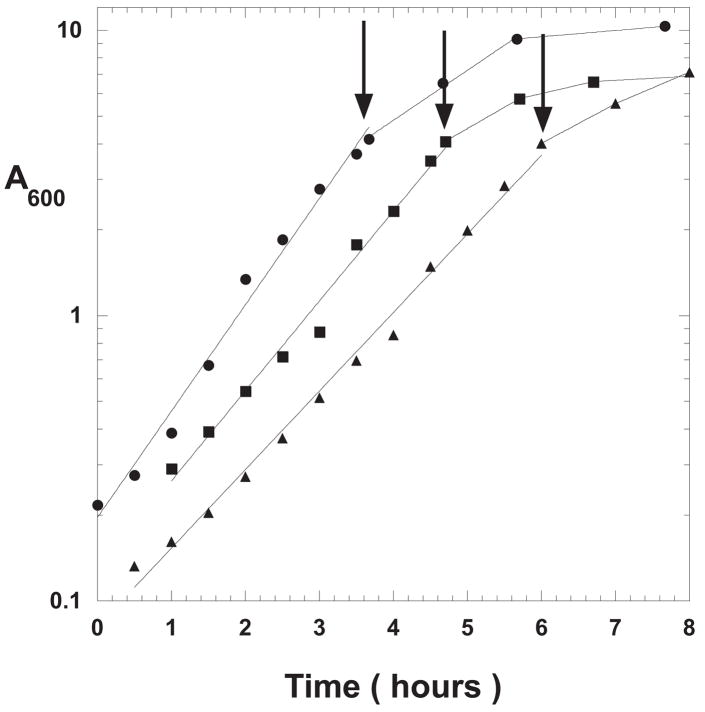

Figure 2. Growth Curves for Temperature vs. Chemically Induced Cells.

An overnight culture of C2984H cells transformed with pcIts ind+ modKlenTaqI was used to inoculate 225 ml TBS plus ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and grown at 32 °C (solid circles). At a cell density of 4 A600 (arrow), the culture was split into two subcultures: Chemical Induction Alone; filled squares (addition of nalidixic acid to 50 μg/ml and 30 °C for the duration of the experiment); and, Temperature Shock Induction; open circles (swirling in a 42 °C water bath for 20 minutes followed by incubation at 37 °C for the duration of the experiment).

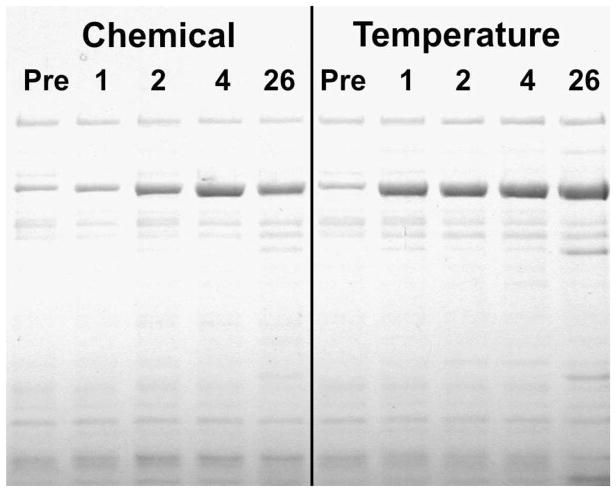

Samples were removed at the times indicated and processed as described in Material and Methods for analysis by 8% SDS-PAGE as shown in Figure 3. The gel shows only the heat treated samples for a comparison of the yields of modKlenTaq1. Each lane represents the protein from a cell sample equivalent to 0.1 A600-ml. The banding patterns showed that there was a low but detectable level of expression before induction. This may be the result of partial inactivation of the repressor at 32 °C [17] since subsequent experiments in which the cultures were incubated at 30 °C showed no detectable expression in the pre-induction samples.

Figure 3. Protein Yields for Temperature Shock vs. Chemically Induced Cultures.

Samples were removed from the cultures described in Figure 2 at times indicated (“Pre”, just prior to induction; 1, 2, 4, and 26 hours post induction) and processed as described in Materials and Methods. Aliquots from the heat-treated samples equivalent to 0.1 A600 Units were analyzed by 8% SDS PAGE. The darkest staining band corresponds to modKlenTaq1: 64,162 Da.

The gel in Figure 3 shows that the temperature shocked culture steadily accumulated modKlenTaq1 over the entire time course of the experiment. Whereas, the chemically induced culture showed somewhat slower accumulation with a maximum sometime between 4 and 26 hours. Gels resolving Total Cell Protein and Soluble Protein samples showed that modKlenTaq1 was only detected in the Total Cell Protein and Soluble Protein samples and not lost to insoluble material (data not shown). Microscopic examination using phase contrast indicated that the cells did not accumulate refractile bodies nor become filamentous in either case following induction (data not shown). Since the repressor gene was present on the plasmid but there was only a single copy of the recA gene in the host chromosome, nalidixic acid induction alone may have been less efficient than temperature shock due to differences in gene copy number. Nevertheless, the 4 hour Chemical Induction Alone and the 4 hour Temperature Shock samples showed comparable levels of expression.

Figure 4 shows the effects of adding both nalidixic acid and simply increasing or shifting the incubator temperature dial to 37 °C. The lanes represent the Total Cell Protein, “TCP,” and the Heat Treated samples, “ΔΔ.” Following induction, the accumulation profile for modKlenTaq1 was comparable to that observed for the Temperature Shock experiments described above. However, the overall yields for both Temperature Shift and Chemically Induced cells were somewhat higher than cells induced by only Temperature Shock judging from comparing the ModKlenTaq1 band intensities to the host proteins in the same lane.

Figure 4. Protein Yields Using Both Temperature Shift and Chemical Induction.

C2984H cells transformed with pcIts ind+ modKlenTaq1 were grown in 100 ml of TBS plus ampicillin in a 500-ml baffle-bottomed erlenmeyer flask at 32 °C with shaking at 150 rpm. When the cells reached a density of 4 A600 the cultures were induced by adding nalidixic acid to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml plus increasing the incubator temperature to 37 °C. Small shake-flasks under these conditions changed temperature from 32 to 37 °C in 12 minutes. Samples were removed at the times indicated and processed as described in Materials and Methods then resolved on an 8% SDS-PAGE. Each lane represents the equivalent of 0.1 A600-ml of cells. The Figure shows “TCP” (Total Cell Protein) and “ΔΔ” (Heat-treated Samples) for each of the time points. The major band in the Heat-treated sample lanes indicates modKlenTaq1.

Expression in recA− Strains

To determine if pcIts ind+ modKlenTaq1 is: 1) “portable,” meaning that it can be used for expression in other strains of E. coli; and 2) capable of efficient expression in recA− strains, the vector was transformed into NovaBlue and DH5α cells. Small scale cultures and protein samples were handled in the same manner as described above for C2984H transformed cells. Figure 5 shows that the growth rates for the recA− strains were slower than for C2984H cells. The doubling times for NovaBlue and DH5a cells were approximately 65 and 60 minutes, respectively, compared to approximately 45 minutes for C2984H cells. The faster growth rate for C2984H cells suggests that recA+ cells may be healthier and be advantageous for scaled-up production. In fact, we have found that other recA+ strains also show faster growth rates compared to isogenic recA− strains (data not shown). Of course, recA− strains can not be chemically induced, therefore, these test cultures were induced using the temperature shock method.

Figure 5. Growth Curves for Different E. coli Strains.

The figure compares the cell density measurements over time for small-scale cultures of C2984H (recA+; circles) and recA− strains NovaBlue (squares) and DH5α (triangles). Each strain was transformed with the expression plasmid, pcIts ind+ modKlenTaq1. All cultures were induced when the cell densities reached 4 A600 (arrows). Since recA−strains can not be chemically induced, all cultures were induced by Temperature Shock as described in the text.

The yields of modKlenTaq1 from NovaBlue and DH5α cells as determined by comparing band intensities on SDS-gels were compared to the yields described in Figure 3 for Temperature Shock Induction (data not shown).

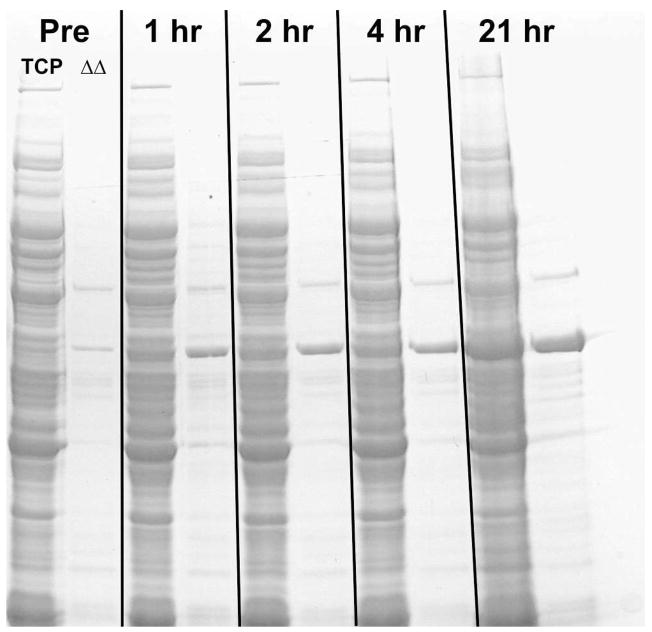

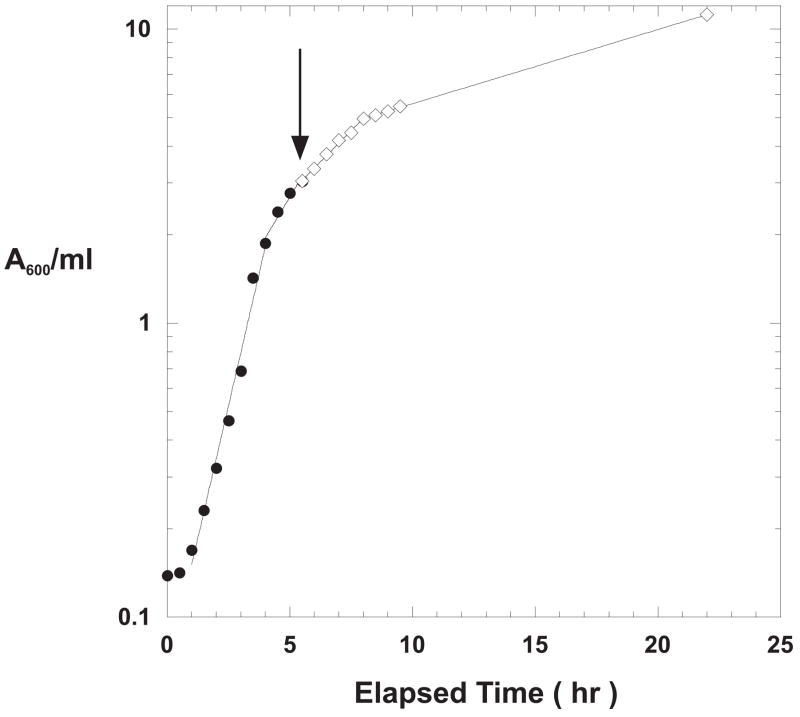

Large Scale Shake-flask Cultures for modKlenTaq1 V649C

Figure 6 shows the growth curve for one of six identical 2.8-liter baffle-bottomed Fernbach flask cultures each containing 1.5 liters of TBS plus ampicillin and inoculated with C2984H cells transformed with pcIts ind+ modKlenTaq1 V649C. The pre-induction incubation temperature was 30 °C to minimize pre-induction expression. One of the six flasks was used to monitor cell growth and to provide samples for gel analyses. The cells grew logarithmically up to a density of approximately 1.5 to 2 A600 with a doubling time of about 50 minutes. When the cell density reached 3 A600 in the large shake-flasks (shown by the arrow in Figure 6), nalidixic acid was added to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml, and the incubator temperature was increased to 37 °C. The Lab-Line Model 3530-1 Orbital Shaker used in these experiments was able to increase the chamber temperature from 30 to 37 °C in 6 minutes. The temperature change within the flasks was much slower taking approximately 25 minutes. After 22 hours of incubation, the final cell density was 11.2 A600 and the final cell yield was 96 gm wet weight. All six flasks showed comparable final cell densities (data not shown).

Figure 6. Growth Curve for Large-scale Shake-flask Expression Using Chemical and Temperature Shift Induction for modKlenTaq1 V649C.

One of six 2.8-liter baffle-bottomed Fernbach flasks each containing 1.5 liters of TBS plus ampicillin (100 μg/ml) was monitored for cell growth. Pre-induction growth was at 30 °C with shaking at 125 rpm. At an A600 of 3, nalidixic acid was added to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml and the temperature setting was increased to 37 °C as described in the text. The arrow indicates the time of induction. The final cell density was 11.2 A600; final cell wet weight was 96 gm.

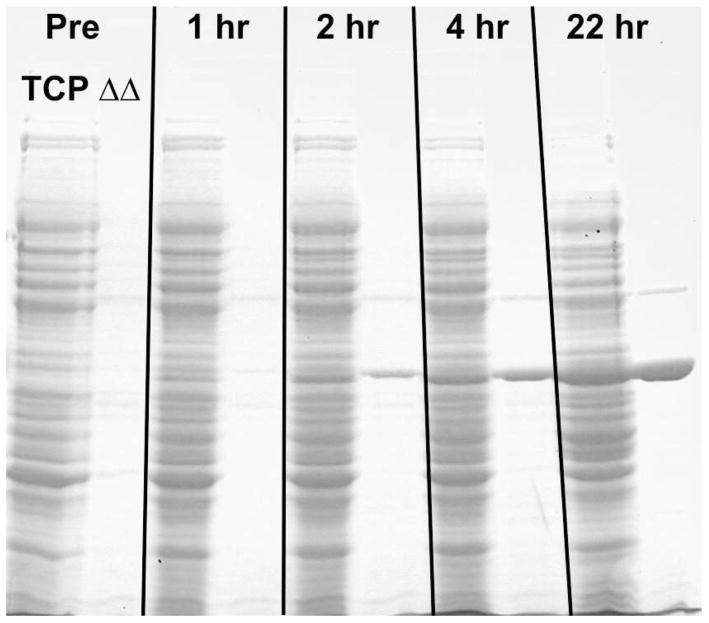

Samples were removed at the times indicated in Figure 7 for gel analysis as described above for Total Cell Protein and Heat-treated samples. Each lane was equivalent to 0.1 A600-ml units of cells as described above. The gel shows no detectable accumulation of modKlenTaq1 in the pre-induction sample indicating more efficient control over transcription from the λPR promoter at 30 °C. Accumulation of modKlenTaq1 was much slower in the large flasks compared to the rate of accumulation observed for the smaller scale cultures; however, the final yield after 22 hours of incubation was comparable in terms of cell specific yield and final cell density. Estimates of yields based upon scanning the stained gels were in the range of 12 to 13% of the total cellular protein (data not shown).

Figure 7. Protein Yields for Large-scale Shake-flask Expression Using Chemical and Temperature Shift Induction.

Samples were removed from the monitored flask described in Figure 5 at the times indicated and processed as described in Materials & Methods. Lanes: 1–2) Pre-induction Total Cell Protein (TCP) and Heat-treated (ΔΔ); 3–4) 1 Hour TCP and ΔΔ; 5–6) 2 Hour TCP and ΔΔ; 7–8) 4 Hour TCP and ΔΔ; and, 9–10) 22 Hour TCP and ΔΔ. A sample equivalent 0.2 A600-ml was loaded onto each lane on an 8% gel as in Figure 3. The major band in the Heat-treated sample lanes is modKlenTaq1 V649C.

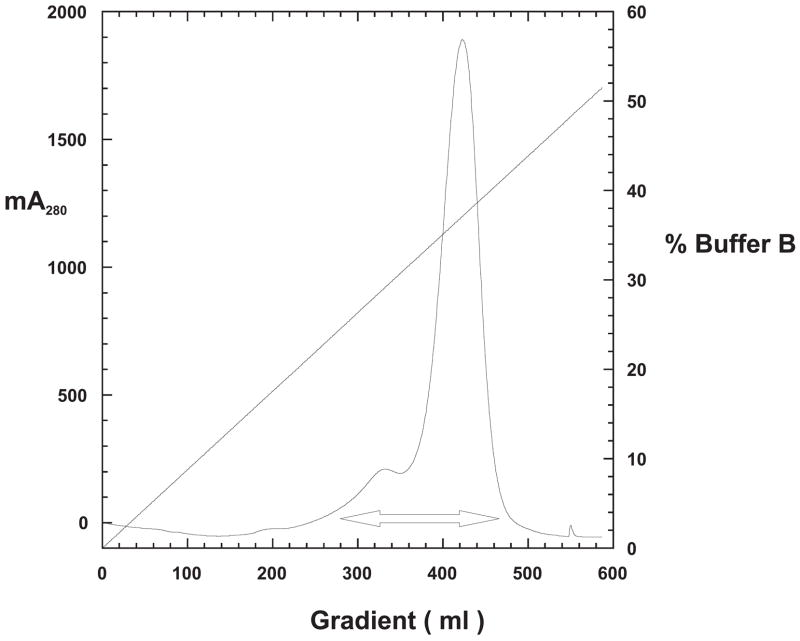

Purification of modKlenTaq1

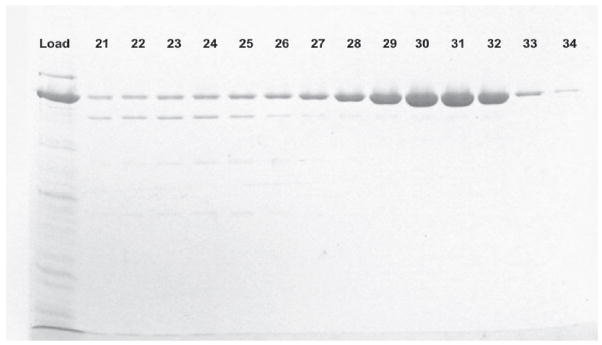

Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase 1 has been shown to be a remarkably thermostable enzyme [5]. Its large fragment (KlenTaq1) has been shown to be even more so [18]. Therefore, we developed a rapid, two-step rapid purification protocol that can easily be scaled-up. Frozen cell pellets were resuspended in Lysis Buffer and treated with lysozyme followed by sonication on ice to shear the DNA and reduce viscosity. The sonicate was slowly poured into an equal volume of Lysis Buffer in a water bath maintained at 80 °C, while stirring constantly. The temperature of the slurry was never allowed to fall below 60 °C during additions to ensure immediate denaturation of host proteins, especially proteases. After all of the sonicate was added, the slurry was incubated with stirring at 80 °C an additional 45 minutes. The slurry then was cooled, the salt concentration was increased, and PEI was added drop wise to precipitate DNA. High salt prevented modKlenTaq1 from binding to the DNA in the PEI-precipitate. After centrifugation, the supernatant was loaded onto two tandem columns: a weak cation exchanger, BioRad-70; followed by an affinity column, Heparin-Sepharose. The cation exchanger preceding the Heparin-Sepharose column removed excess PEI. After washing both columns in tandem until the A280 returned to baseline, the Heparin-Sepharose column was isolated and then modKlenTaq1 was eluted using a 5.5 × column volume linear gradient (100 mM to 1000 mM NaCl). Figure 8 shows the elution profile exhibited a single large peak with a leading shoulder. Samples from peak fractions designated by the double-headed arrow in Figure 8 were resolved by SDS-PAGE as shown by gel analysis in Figure 9. Peak fractions corresponding to gel lanes #29 through #32 were pooled. The final yield of purified modKlenTaq1 V649C in this example was 285 mg.

Figure 8. Elution Profile for the Heparin-agarose Affinity Column.

A sample equivalent to 48 gm of cell wet weight was processed as described in Materials and Methods and following treatment with PEI and centrifugation, the supernatant was pumped directly onto tandem BioRex-70 and Heparin-sepharose columns. After washing until the A280 signal returned to baseline, a 100 to 1000 mM NaCl-gradient was used to elute only the Heparin-sepharose column. ModKlenTaq1 eluted from the column at approximately 400 mM. The figure shows a plot of the protein profile (milli-equilivents, mA280) and conductivity (straight line, 100% Buffer B = 1000 mM NaCl) versus gradient volume. The double-headed arrow indicates the portion of the gradient shown as gel protein profiles in Figure 9. Each column fraction was 14 ml.

Figure 9. Gel Analysis of the Column Fractions.

Five μL aliquots from peak column fractions were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE.

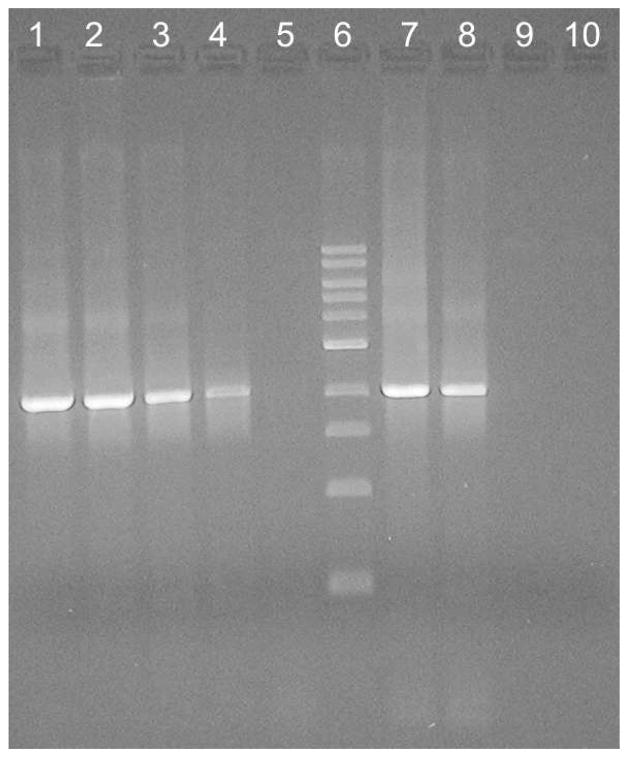

Enzyme activity was estimated by PCR titration experiments [13] comparing dilutions of Stoffel Fragment which is a commercially available N-terminal 289 amino acid truncated form of Taq DNA polymerase to dilutions of purified modKlenTaq1 V649C as shown in Figure 10. The gel shows that modKlenTaq1 V649C is active in PCR and that a 1:20 dilution of purified material matches the band intensity for an identical reaction containing 1.25 Units of Stoffel Fragment. The overall yield for this preparation then was approximately 1.4 × 106 Units for this enzyme by titration.

Figure 10. Activity Measurement for modKlenTaq1 V649C by PCR Titration.

Dilutions of either commercially available Stoffel Fragment of Taq DNA polymerase I or purified modKlenTaq1 V649C were added to PCR reactions (final reaction volume 50 μL) as described in Materials and Methods to amplify a 2 kbp region of the E. coli groEL/S operon in plasmid pBB528 [14]. Stoffel Fragment is a 289-amino acid N-terminal truncation of Taq DNAP I that is very similar to modKlenTaq1, a 280 amino acid truncation. Lanes: 1 –5) Stoffel Fragment at 10, 5, 2.5, 1.25 and 0.625 Units per reaction, respectively; Lane 6) 1 kbp DNA standard set from New England Biolabs (bands from top to bottom represent: 10, 8, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.5, 1, and 0.5 kbp); and, Lanes 7–10) modKlenTaq1 V649C at 1/10, 1/20, 1/40, and 1/80 dilutions, respectively.

Discussion

modKlenTaq1 Expression Using Chemical vs. Temperature Induction

The lambda rightward promoter, λPR, is normally active during the lytic cycle of this temperate bacteriophage and is repressed during lysogeny. Efficient repression is necessary to maintain the lysogenic state and is provided by binding of the lambda repressor to the λOR operator which, in turn represses the so-called anti-terminator gene, λcro. As long as the repressor concentration is moderately high, λcro remains repressed. Therefore, the region of the lamdba genome spanning the λcI repressor, λOR and λPR sequences is of special interest as a self-contained transcriptional control unit. Since the wild-type λcI repressor can be inactivated via a host encoded RecA protein through proteolysis, treatment of E. coli with either mitomycin-C or nalidixic acid causing induction of RecA can be used to induce heterologous gene expression on numerous plasmid constructs [16]. In one example, it has been possible using the leftward promoter to over express the gene for transcription factor rho to very high levels (30 to 40% of total protein) when it was induced using nalidixic acid in recA+ host cells that were also lambda cI+ (wild-type repressor) cryptic lysogens [19]. Taq DNA polymerase has been expressed at 1–2% of the total cellular protein using a pPR-TGATG-1 expression vector with the temperature-sensitive lambda repressor, λcI857, onboard the plasmid [5]. Therefore, we chose to use modKlenTaq1 expression as measure of expression for the plasmid, pcIts ind+.

Most expression vectors utilizing either of the lambda promoters, λPL or λPR or both, have been controlled by the temperature sensitive λcI857 repressor [3] which means that expression is limited to lysogenic hosts. Lysogens can be a disadvantage since all of the phage genes in the lysogen are induced along with the desired gene on the expression vector. One of the induced genes is lambda lysogen that can cause cell lysis from “within” limiting final cell densities and exposing product proteins to proteolysis following lysis of the host cells.

Typically, λcI857 repressor-based expression vectors are induced by Temperature Shock that requires the culture temperature be rapidly raised to 42 °C, held at 42 °C for 20 minutes, and then lowered to 37 °C. Rapidly raising the temperature of several large flasks has always been a practical problem for shake-flask cultures. Therefore, we have combined several desirable features in an expression construct that uses only the temperature sensitive form of the lambda repressor gene namely, λcIts ind+, thus providing for both temperature and/or chemical induction. As shown in Figure 1, the expression vector, pcIts ind+, contains the region from lambda, λcI857 ind 1 Sam7, that includes the λcI857 ind 1 repressor, the λPR promoter and the start codon of the λcro gene. The repressor was back-mutated to be ind+ while maintaining the temperature sensitive genotype. Restoring ind+ makes the repressor protein sensitive to RecA cleavage. The coding region for the λcro gene was deleted and a unique Nde1 insertion restriction site was constructed to overlap its ATG initiation codon. This construction added an additional base and changed a base in the sequence between the Shine-Dalgarno site and the initiator codon (…AGGAGGTTGT-ATG… to … AGGAGGTTcaT-ATG…). We found that despite the high %GC content of the coding sequence for modKlenTaq1, it was not necessary to use a “stutter-stop-start” pre-coding segment to avoid secondary structure in the mRNA [5]. A unique Sph1 restriction site was constructed immediately ahead of the T1T2 ribosomal terminators from the E. coli rrnB operon in the plasmid pUC19-T1T2 [6]. This plasmid has as its origin of replication, the high copy number pUC ori.

A portion of the Taq DNA polymerase 1 gene was amplified with PCR primers containing the same cryptic restriction sites to allow insertion of the modKlenTaq1 coding region into the Nde1 and Sph1 sites as shown in Figure 1 generating the plasmid, pcIts ind+ modKlenTaq1.

The expression plasmid, pcIts ind+ modKlenTaq1, was tested initially in the recA+ strain, C2984H. Small volume cultures were used to survey the effects of temperature shock vs. chemical induction. As shown in Figure 2, the growth curves for both types of induction were similar; however, gel analysis shown in Figure 3 indicates: 1) that the pre-induction temperature of 32 °C was not high enough to completely repress synthesis of modKlenTaq1 (at least as detectable on gels); and, 2) that there were differences in the rate of accumulation of modKlenTaq1. Chemically induced cultures typically lagged behind temperature shocked cultures. This observation suggested that thermal inactivation of the repressor must either begin at a temperature as low as 32 °C or that the level of repressor molecules was still too low to completely repress transcription despite the fact that the repressor gene was located on the same plasmid. We favor the former explanation because subsequent tests in which the pre-induction temperature was maintained at 30 °C showed no detectable pre-induction modKlenTaq1 band. Consequently, all large scale experiments were conducted at a pre-induction temperature of 30 °C and no pre-induction expression was detected on gels. Further testing will be required to determine just how tight repression is and whether or not this expression vector can be used to control expression of “lethal” genes in E. coli.

As mentioned above, λcI857 repressor controlled expression systems must be induced by Temperature Shock in order to achieve full induction through complete inactivation of the repressor. We have found that adding nalidixic acid and a simple temperature shift was sufficient to also achieve full induction as shown by comparing the final yields of modKlenTaq1 relative to other host protein bands in the same lanes as shown in Figures 3 and 4. This observation opened up the possibility of achieving full induction in multiple shake-flasks in a standard gyratory shaker incubator. In fact, we were eager to test whether or not combining this possibility with the more rapid growth rates observed for for recA+ strains as shown in Figure 5 would greatly facilitate shake-flask production of recombinant proteins for mass intensive studies.

Large-scale Shake-flask Expression Using Both Chemical and Temperature Induction

As shown in Figure 7, the yield for modKlenTaq1 relative to heat stable host proteins in the same lane was comparable to the yields achieved in smaller flasks despite the apparent lower availability of oxygen. The final cell density at harvest was moderately high reaching 11.2 A600 yielding 96 gm total cell wet weight or 10.6 gm/liter.

A rapid affinity column-based purification protocol yielded 285 mg (or approximately 32 mg/L) for a mutant form of modKlenTaq1 (V649C) which has been extensively characterized [11]. The purified enzyme was active in a PCR-based titration activity assay as shown in Figure 10 and in pre-steady state equilibrium titration, DNA binding studies (data not shown).

General usefulness of the pcIts ind+ expression vector

There are several advantages of the pcIts ind+ vector that should make it generally applicable to achieve high levels of protein expression. First, this vector is “portable” meaning that it can be used in any E. coli host, notably recA+ strains, because it carries an on-board repressor gene. Therefore, a wide variety of strains can be rapidly screened for improved expression of soluble product proteins. Second, this vector can be induced either thermally or chemically or both making it possible to optimize the induction method and timing for the maximum soluble yield of a desired protein or enzyme. Third, this vector lends itself to easy, full induction of heterologous genes in shake-flasks without the need for a rapid temperature jump to 42 °C. Fourth, this vector does not require hosts carrying “cryptic” lysogens that encode repressors or RNA polymerase genes. Thus, induction of the desired product does not also induce undesirable enzymes like lambda or T7 lysogens. Finally, this vector lends itself well to high cell densities thus improving yields per fermentation cycle and reducing the need to do multiple runs to accumulate sufficient protein for mass intensive studies like transient kinetics or crystallography. In our current work, we have achieved a 20-fold increase in yield of rat kinesin in E. coli through optimizing the host strain, the timing of, and type of induction, and the time of harvest (unpublished results).

Abbreviations used

- ATCC

American Type Culture Collection

- DNAP

DNA polymerase

- ΔΔ

heat-treated protein sample

- EDTA

ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid

- LB

Luria-Bertani broth

- A600

absorbance at 600 nm

- A280

absorbance at 280 nm

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PEI

polyethyleneimine

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- TBS

Terrific Broth plus Salts medium

- TCP

Total cell protein

- TRIS

tris hydroxymethylaminoethane

- TYE

tryptone-yeast extract medium

Footnotes

A patent has been filed in the names of John W. Brandis and Kenneth A. Johnson for the expression vector, pcIts ind+, PCT No. PCT/60/943,507 June 12, 2007. There is no other conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Johnson KA. Rapid quench kinetic analysis of polymerases, adenosinetriphosphatases, and enzyme intermediates. Methods in Enzymol. 1995;249:38–61. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)49030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baneyx F. Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1999;10:411–421. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(99)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makrides SC. Strategies for achieving high-level expression of genes in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:512–538. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.3.512-538.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yanish-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patrushev LI, Valiaev AG, Golovchenko PA, Vinogradov SV, Chikindas ML, Kieselev VI. Cloning of the gene for thermostable Thermus aquaticus YT-1 DNA polymerase and its expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Biol (Mosk) 1993;27:1100–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brosius J, Ulrich A, Baker MA, Gray A, Dull TJ, Gutell RG, Noller HF. Construction and fine mapping of recombinant plasmids containing the rrnB ribosomal RNA operon of E. coli. Plasmid. 1981;6:112–118. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(81)90058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tartoff KD, Hobbs CA. Improved media for growing plasmid and cosmid clones. Bethesda Research Labs Focus. 1987;9:12. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller JH. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; NY: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brock TD, Freeze H. Thermus aquaticus gen. n. and sp. n., a non-sporulating extreme thermophile. J Bacteriol. 1969;98:289–297. doi: 10.1128/jb.98.1.289-297.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korolev S, Murad N, Barnes WM, DiCera E, Waksman G. Crystal structure of the large fragment of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase 1 at 2.5 A: Structural basis for thermostability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9264–9268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothwell PJ, Mitaksov V, Waksman G. Motions of the fingers subdomain of KlenTaq1 are fast and not rate limiting: Implications for the molecular basis of fidelity in DNA polymerases. Molec Cell. 2005;10:345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engleke DR, Krikos A, Bruck ME, Ginsburg D. Purification of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase expressed in E. coli. Analyt Biochem. 1990;191:396–400. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Marco A, Deuerling E, Mogk A, Tomoyasu T, Bukau B. Chaperone-based procedure to increase yields of soluble recombinant proteins produced in E. coli. BMC Biotech. 2007;7:32–41. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Remaut E, Stanssens P, Fiers W. Plasmid vectors for high-efficiency expression controlled by the PL promoter of coliphage lambda. Gene. 1981;15:81–93. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(81)90106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts JW, Devoret R. In: Lambda II. Hendrix R, Roberts J, Stahl F, Weisberg R, editors. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: 1983. pp. 130–133. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villaverde A, Benito A, Viaplana E, Cubarsi R. Fine regulation of cI857-controlled gene expression in continuous culture of recombinant Escherichia coli by temperature. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3485–3487. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.10.3485-3487.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnes WM. The fidelity of Taq polymerase catalyzing PCR is improved by an N-terminal deletion. Gene. 1992;112:29–35. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mott JE, Grant RA, Ho YS, Platt T. Maximizing gene expression from plasmid vectors containing the λPL promoter: Strategies for over producing transcription terminator factor ρ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:88–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.1.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]