Abstract

A randomized trial of substance abuse treatment programs tested whether “enhanced profiles,” consisting of feedback and coaching about performance indicators, improved the performance of residential, methadone, and detoxification programs. These enhanced profiles were reviewed during quarterly on-site visits between October 2005 and July 2007. The performance indicators were the percentage of clients completing referrals to a lower level of care, and the percentage of clients admitted to a higher level of care within 30 days of discharge. Control programs received only “basic profiles,” consisting of emailed quarterly printouts of these performance indicators. Effectiveness was evaluated using hierarchical linear models with client-level information nested within agencies and regions of the state. Treatment programs receiving enhanced profiles (n = 74) did not perform significantly differently from those receiving only basic profiles (n = 29) on either performance measure. To improve performance, interventions with greater scope and incentives may be needed.

Keywords: Profiling, Continuity, Readmissions, Performance measures, Randomized

Introduction

Demonstrations of wide variability in clinical practice [Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA 2004)] and gaps between evidence and routine practice show the potential value of wider implementation of best practices (National Quality Forum 2007). For example, one study found only about one in ten patients with alcohol dependence received treatments that were consistent with scientific knowledge (McGlynn et al. 2003). With severely constrained budgets, public funders are searching for innovative and effective ways to improve the quality of substance abuse treatment services. Connecticut’s Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (DMHAS) was among the early adopters of provider profiling or feedback on performance, by first initiating quarterly distribution of profiles in 2001. During a period of leadership change, DMHAS suspended the distribution of basic profiles in April 2004. Basic profiles were re-introduced in October 2005 and operationally defined as the control condition in the present experiment. A related paper examines basic profiling (Daley et al. 2010). This article describes the implementation in 2005 and evaluation of enhanced profiling through a randomized trial in the public sector in Connecticut.

Provider profiling involves issuing periodic reports to health care programs comparing their performance on selected clinical standards to that of their peers (Flynn et al. 1997; Friedmann et al. 2000; Hagland 1998; Institute of Medicine 2006a; Joshi and Bernard 1999; Kizer et al. 2000; Mark and Garet 1997; McCorry et al. 2000; Mohan et al. 2006). The intention of profiling is to inform providers of their relative performance, raise awareness of problems and opportunities to improve, and encourage them to identify and adopt improved practices (e.g., Mohan et al. 2006).

Within the addictions field, one of the goals of profiling has been to encourage providers to adopt clinical practices that have been found to be associated with abstinence or stable recovery (Donabedian 1985; Eddy 1998; Garnick et al. 2009; McCorry et al. 2000). One specific practice was to help patients transition from higher to lower intensities of treatment. The goal of such continuity is to reinforce the gains achieved in intensive treatment, since better continuity promotes abstinence and reduces the likelihood of relapse and recidivism (Institute of Medicine 2006a, b; McKay 2001, 2005, 2009; Moos and Moos 2003). Despite this, nationally only about 17% of clients in the public treatment system complete the recommended continuum of care (OAS 2005).

Although it has been operationalized differently, continuity has been adopted as a quality measure by the Department of Veterans Affairs (Harris et al. 2006; Schaefer et al. 2004; Schaefer et al. 2008), the American Society on Addiction Medicine (ASAM) and the American Psychological Association. In addition, rapid re-admissions into acute care services are also considered problematic because they signify lack of clinical progress, consume expensive resources and can be a marker of inadequate or insufficiently effective community services (Barnett and Swindle 1997; Mattick and Hall 1996; Mertens et al. 2005; Thakur et al. 1998). The Washington Circle’s initiation and engagement measures similarly use claims to monitor provider performance (Garnick et al. 2009).

As evidence on profiling has accumulated, the impact of profiling in medical care was found to be mixed (Axt-Adam et al. 1993; Balas et al. 1996; Grimshaw et al. 2001; Foy et al. 2005; Mugford et al. 1991; O’Reilly 2008; Simon and Soumerai 2005; Wones 1987). Several well-designed trials that controlled for secular trends and other factors were unable to attribute any improvements directly to profiling (Dziuban et al. 1994; Ghali et al. 1997). Fung et al. (2008) concluded that profiling has served more as a catalyst for other quality improvement activities than a consistently favorable intervention for medical outcomes. However, many studies have reported marked improvement in health indicators after the introduction of profiling in both substance abuse treatment (Finney et al. 2000) and medical care (Kazandjian and Lied 1998).

We hypothesized that continuity and quality of care might be improved by “enhanced profiling,” an approach that combined the content of profiling with visits by state regional managers. We collaborated with DMHAS to randomize some providers to an “enhanced profiling” arm where they could receive additional coaching and instruction in quality improvement practices from their regional managers. The coaching component of enhanced profiling was adapted from the network for the improvement of addiction treatment (NIATx) program (McCarty et al. 2007; Wisdom et al. 2006; NIATx 2009). When the experiment began in October 2005, about 30% of admissions from higher levels of care (detoxification or residential) connected to a lower level of care within 30 days. Meanwhile, about a quarter of these admissions were followed by a re-admission to the same or higher level of care within 30 days, an event DMHAS sought to minimize.

Materials and Methods

Randomization of Agencies

In October 2005, approximately two-thirds of the 52 agencies (103 programs) that provided residential, detoxification and methadone maintenance services (ASAM levels IV.2D, III.7D, III.7R, III.3 and I.3) to approximately 28,000 low income general assistance clients annually were randomly assigned to enhanced profiles (36 agencies containing 74 programs). The remaining one-third of the agencies (16 agencies containing 29 programs) received basic profiles only. No programs were excluded from randomization or follow up. Randomization was carried by the research team using the random uniform distribution (RANUNI) function, SAS Version 9.1. Because some programs are managed together in multi-modal facilities, the units of randomization needed to be agencies, rather than programs although this resulted in some imbalance in the levels of care by arm. Randomizing programs independently, or by stratum (such as level of care) was problematic because we were concerned about contamination if two programs in the same agency were in opposite conditions and the agency director would have been in both the control and intervention conditions simultaneously. The enhanced profiling group was deliberately made larger than the basic profiling group to increase the statistical power of possible future research that would subdivide the enhanced profiling group. To increase objectivity, randomization and data analysis were conducted at Brandeis University, while the intervention was delivered or managed by DMHAS. Randomization details, including a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram showing eligible and excluded facilities, are available from the corresponding author.

Description of Basic Profiling

Basic profiles consisted of quarterly spreadsheet reports that were sent electronically to all treatment programs. The reports compared each program’s performance on continuity and re-admissions to that of all other programs in the state in the same level of care. These two performance measures were operationalized as follows:

Re-admissions: The number of client discharges with authorization for admission to a higher level of care within 30 days of discharge, divided by the total number of client admissions to the originating treatment program each quarter.

Connect-to-care: The number of client discharges with authorization for admission to a lower level of care within 30 days of discharge, divided by the total number of admissions to the originating treatment program each quarter. This measure is used for detoxification and residential programs, but not for methadone maintenance programs which are considered a stable level of care.

Description of Enhanced Profiling Intervention

After meetings with the regional managers, treatment providers, agency directors and state officials to obtain their input, we coordinated a 1-day training session with DMHAS regional managers and their staff in September 2005, in preparation for the start of the randomized experiment. The teaching materials were adapted from the NIATx Plan-Do-Study-Act procedures (McCarty et al. 2007; NIATx 2009 www.niatx.net), with input from a NIATx consultant (Jay Ford, personal communication, 2005). The intention was to discuss and select strategies for regional managers to help substance abuse treatment providers adopt clinical practices from the literature or their personal experience that had been shown to enhance continuity of care (McKay 2009; Schaefer et al. 2004, 2008; Dennis and Scott 2007). Plausible strategies included:

Improving referral networks with providers at the next level of care,

Encouraging continuity between staff and clients,

Linking clients with additional resources in the community,

Making follow-up telephone calls to recently discharged clients to make sure that they completed referrals to the next level of care,

Introducing clients to the clinicians who will treat them at the next level of care,

Contacting counselors at the next level of care to ensure that referred clients had arrived,

Facilitating access to transportation and child care.

Consistent with NIATx quality improvement techniques, regional managers were encouraged to teach providers to conduct a walk-through exercise at their sites to discover faulty processes, to solicit suggestions from consumers, clinicians and staff, to experiment with different procedures, do rapid cycle testing, and make an action plan to improve the referral process. The experimental condition of enhanced profiling consisted of the basic profiling reports, augmented with quarterly site visits and coaching from regional managers to instill new practices aimed at improving performance.

The researchers and DMHAS deliberately designed the study as an effectiveness evaluation of basic and enhanced profiling that could be sustained if effective. As grant funds tend to be ephemeral and state funds scarce, the intervention was designed to place virtually no demands on DMHAS. DMHAS deliberately implemented both basic and enhanced profiling within the existing system of publicly funded behavioral health care. Basic profiles were prepared by existing contractors and mailed by state officials. Existing DMHAS regional staff was asked to conduct training sessions and site visits on top of existing responsibilities. Both basic and enhanced profiles were confidential, so agencies received neither peer recognition for excellent performance nor public embarrassment for mediocrity.

Description of Site Visit Reports

As a qualitative component of the study, regional managers summarized their visits to agencies in the experimental arm. These site-visit reports documented procedural information (date of visit, number of staff present, length of visit, etc.) and topics discussed. Two members of the research team were responsible for monitoring and analyzing data from these site visits. Over the 21 months of the study, one member of research team met with the managers in person eight times with more frequent telephone contact to ensure compliance with protocols. All regional staff conducted visits and none of the study sites closed, merged, or refused enhanced profiling visits during the study period.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative assessments of agency performance were possible with quarterly profiling reports covering the 28 quarters from July 2000 through June 2007, showing the proportions of discharges in that quarter that had authorizations for entry to a lower level of care within 30 days, or led to actual admission to a higher level within 30 days. The 4.5 years of pre-randomization data allowed for an important covariate. Profiling reports were provided by DMHAS’s managed care vendor, Advanced Behavioral Health. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1.

Two-tailed unpaired student’s t-tests were conducted to determine if there were significant differences in connect-to-care and re-admission scores between the enhanced and the basic group during the enhanced profiling period (October 2005 through June 2007). To ensure that the two groups were matched at baseline, t-tests also compared scores for the “basic” and “enhanced” groups in the years prior to profiling. To test the effects of enhanced profiling quantitatively, we used generalized estimation equations (GEE). Specifically, we used SAS general modeling procedure (PROC GENMOD) with repeated measures and a link function for data with a normal distribution, a maximum likelihood method of parameter estimation for correlated data (clients within the same treatment programs). As used by previous researchers, these hierarchical models were used in order to quantify within-provider variation and improve estimates for small providers (Huang et al. 2005; Krumholz et al. 2006). Our models tested whether enhanced profiling was associated with improved scores on either of the performance measures after controlling for performance in the 2 years prior to randomization. Within the five levels of care, the 103 treatment programs were used as classification variables. Profile likelihood and Wald confidence intervals were calculated for the GEE parameter estimates.

Independent Variables

The unit of analysis was a program for a reporting period of 3 months. Control variables included the continuous variable time representing the 24 quarters between July 2000 and June 2007, a dichotomous variable denoting the enhanced profiling period, the baseline performance of the program, and an interaction term between time and the dichotomous variable.

Analyses by Region and Level of Care

Although the study was neither designed nor powered statistically to examine regional differences, the researchers compared changes in rates of connect-to-care and readmissions among the five regions with a Scheffe test as a post hoc analysis to test for unexpected large regional variations. These could arise due to differences in profiling implementation, receptivity, or local resources. GEE regressions were estimated for each of the five levels of care separately to assess whether there was improvement for the enhanced group.

Approval to conduct this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of Brandeis University and the State of Connecticut.

Results

Table 1 describes the treatment programs assigned to the experimental enhanced profiling and basic profiling control groups by region and level of care.

Table 1.

Characteristics of programs assigned to enhanced and basic profiling

| Program characteristics | Enhanced |

Basic |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Level of care | ||||

| Acute detoxification | 15 | 65 | 8 | 35 |

| Residential detoxification | 4 | 36 | 7 | 64 |

| Short term residential | 9 | 69 | 4 | 31 |

| Long term care | 28 | 82 | 6 | 18 |

| Methadone maintenance | 18 | 82 | 4 | 18 |

| Region in Connecticut | ||||

| 1 – Southwest | 14 | 64 | 8 | 36 |

| 2 – Southeast | 14 | 78 | 4 | 22 |

| 3 – Northeast | 10 | 63 | 6 | 37 |

| 4 – Hartford area | 25 | 74 | 9 | 26 |

| 5 – Northwest | 11 | 85 | 2 | 15 |

| Total | 74 | 72 | 29 | 28 |

Impact on Performance Measures

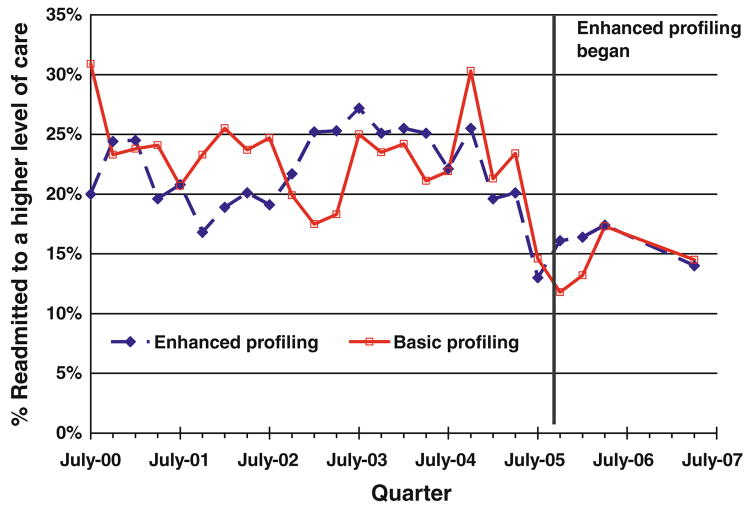

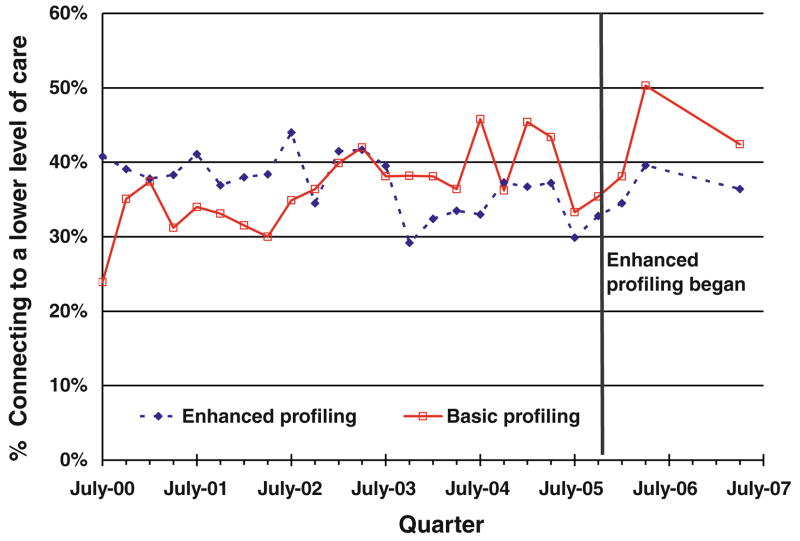

Figures 1 and 2 show quarterly average scores on the two outcomes of interest for agencies that were randomized in October 2005 to either enhanced or basic profiling. The data show that agencies were well matched, in that pre-randomization rates of connect-to-care and re-admissions were comparable between study arms. Findings also show that rates fluctuated several percentage points among quarters and between treatment arms. The data also point out the strength of the randomized design used here in distinguishing study interventions from environmental influences. Rates of re-admissions declined beginning in mid-2004, perhaps due to concurrent initiatives, such as DMHAS’s case management program for clients with frequent readmissions. The fact that this decline affected both arms of the study and occurred prior to the initiation of enhanced profiling shows that was likely unrelated to profiling.

Fig. 1.

Re-admissions to a higher level of care, July 2000 through June 2007

Fig. 2.

Rates of connecting to a lower level of care, July 2000 through June 2007

T-tests (Table 2) comparing scores for the latest profiling period suggest that there were no significant differences between the enhanced and basic groups on either readmissions (16% vs. 14%) or connect-to-care (40% vs. 44%). In the quarters prior to profiling, t-tests indicate that baseline measures for the enhanced and basic groups on readmissions (22% vs. 23%) and connect-to-care (36% vs. 37%) were virtually equivalent, confirming that the intervention and control groups were generally comparable prior to the study.

Table 2.

Comparison between groups and time periods in rates of readmission and connecting to a lower level of care

| Performance measure | Level (%) | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage re-admitted to a higher level of care | |||

| Enhanced group since enhanced profiling | 15.97 | ||

| Basic group since enhanced profiling | 14.19 | −0.93 | ns |

| Enhanced group in year prior to enhanced profiling | 21.90 | ||

| Basic group in year prior to enhanced profiling | 22.81 | 0.89 | ns |

| Percentage connecting to a lower level of care | |||

| Enhanced group since enhanced profiling | 39.91 | ||

| Basic group since enhanced profiling | 43.90 | 1.49 | ns |

| Enhanced group in year prior to enhanced profiling | 36.39 | ||

| Basic group in year prior to enhanced profiling | 36.91 | 0.44 | ns |

ns denotes not significant

Results from the GEE analysis also suggest that the “enhanced profiling” had no significant impact on re-admissions compared to basic profiling. This analysis controlled for secular trends, the baseline performance of the enhanced group and trends continuing at the re-introduction of basic profiling (see Table 3). The results from the GEE analysis on connecting to a lower level of care also suggest that the enhanced profiling had no additional impact on connect-to-care (see Table 4). Regional analyses, not shown in tables, found no significant variation in success among regions. There were also no significant differences in improvement for the enhanced group in any of the levels of care examined.

Table 3.

Generalized estimation equations analysis with repeated measures: Readmissions to a higher level of care July 2000 through June 2007

| Variable | Parameter estimates | Standard error | Confidence interval |

Z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lower | upper | |||||

| Intercept | 0.2378 | 0.0195 | 0.1996 | 0.2760 | 12.21 | < 0.0001 |

| Time (quarters) | −0.0008 | 0.0011 | −0.0030 | 0.0014 | −0.73 | 0.464 |

| Enhanced profiling period | −0.0764 | 0.0167 | −0.1092 | −0.0436 | −4.57 | < 0.0001 |

| Enhanced profiling arm | −0.0091 | 0.0238 | −0.0557 | 0.0376 | −0.38 | 0.7031 |

| Interaction: enhanced profiling period and enhanced profiling arm | 0.0269 | 0.0192 | −0.0107 | 0.0644 | 1.40 | 0.1614 |

Enhanced profiling period is 1 for period that enhanced profiles were active (beginning October 2005) and 0 previously. Enhanced profiling arm is 1 for facilities randomized to enhanced profiling, and 0 for those randomized to basic profiling. Interaction term is 1 for observations corresponding to programs randomized to enhanced profiling and quarters during enhanced profiling

Table 4.

Generalized estimating equations analysis with repeated measures: Connecting to a lower level of care July 2000 through June 2007

| Variable | Parameter estimates | Standard error | Confidence interval |

Z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Intercept | 0.3640 | 0.0251 | 0.3148 | 0.4131 | 14.52 | < 0.0001 |

| Time (quarter) | 0.0004 | 0.0016 | −0.0027 | 0.0036 | 0.27 | 0.7873 |

| Enhanced profiling period | 0.0645 | 0.0324 | 0.001 | 0.128 | 1.99 | 0.0465 |

| Enhanced profiling arm | −0.0055 | 0.0315 | −0.0672 | 0.0561 | −0.18 | 0.861 |

| Interaction: experimental and enhanced versus basic profiles | −0.0345 | 0.0324 | −0.0979 | 0.029 | −1.07 | 0.2868 |

Findings From Site Visit Reports

Over the first 21 months (through July 2007) 66 site visit reports were filed covering 111 individual visits. They showed that at least 92% of the enhanced profiling agencies (i.e., 33 of 36) received a visit. Programs that did not receive a visit tended to be large hospital based facilities located in remote areas that served only one or two clients a year. Site visit reports, which ranged from two to eight double-spaced pages, documented procedural information, each program’s current connect-to-care and re-admission rates, and topic discussed. Visits by the regional managers averaged 2.5 h (and ranged from 2 to 3.1 h) and focused on discussing strategies to improve continuity of care and imparting information about quality improvement. Each agency received 2.4 visits on average (with regional averages ranging from 2.2 to 2.8 visits). Facilities were eager to discuss ways they could improve their performance on completing client referrals and reducing readmissions. Almost all providers could answer questions about where specific clients had been referred and 80% of facilities (i.e., 29 of 36) reported adopting an action plan to address current policies or practices that were preventing their clients from connecting to further treatment. For example, several programs adopted a policy of calling clients after discharge, another made use of a Latino referral specialist and another conducted a client satisfaction survey.

About three-fourths of the visits entailed explanations about quality improvement, some of them quite extensive. The visits entailed a team of two or three DMHAS officials (the regional manager and assistant from the agency’s region and sometimes a staff member from the adjoining region) equipped with printouts of agency statistics from several previous quarters and detailed explanations. While negative reactions had been feared, in fact treatment agency staff appeared to be impressed by the interest and knowledge of the DMHAS officials and the precision of the printouts.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that the enhanced profiling program did not improve performance over basic profiling, measured as re-admissions to higher levels of care, or authorizations for admissions to lower levels of care. The design of the enhanced profiling intervention contained many elements that seemed promising. At the outset, DMHAS leadership and treatment providers were enthusiastic about providing feedback to treatment agencies. For example, a 2004 survey of DMHAS treatment providers found that 83% of agency directors were in favor of profiling (Shepard and Adams 2004). The training program for enhanced profiling for regional managers drew on previous work about coaching from the NIATx project and profiling from the literature (NIATx 2009; Jamtvedt et al. 2006; Axt-Adam et al. 1993; Grimshaw et al. 2001; Hagland 1998).

This trial of enhanced profiling was deliberately designed as an effectiveness study. It was designed to use existing personnel, supervision, and travel resources, with no external inputs except for contributions to the initial training sessions and training materials from the research team. This design ensured that the intervention being tested was one that could be widely used by public sector agencies. Furthermore, as the experiment included all agencies in the chosen levels of care—not just a self-selected group—findings should be broadly generalizable.

To understand better why enhanced profiling proved unsuccessful here in lowering re-admission rates and increasing connect-to-care, two mediating variables were examined through the site visit reports and researchers’ observations: (a) the frequency of DMHAS staff contacts with programs and (b) indications from comments about providers’ implementation of recommended strategies. The original design of the intervention recommended quarterly site visits to each program assigned to enhanced profiling, or seven times over the 21-month period of intervention. The average of 2.4 visits per agency represented only 34% of the target and was equivalent to one visit every 8.8 months. The quality assurance literature generally uses quicker feedback (Jamtvedt et al. 2006; McCarty et al. 2007). Furthermore, the comments in the site visit reports and researchers’ observations from some site visits documented virtually no increases in recommended strategies in response to enhanced profiling. Turnover in DMHAS leadership after the agency’s initial agreement to participate in this study, new initiatives, competing demands on staff time, and limited emphasis or follow up from DMHAS management all limited the priority for enhanced profiling visits. These circumstances highlight the importance of organizational leadership and the constraints from reliance entirely on existing resources.

By contrast, the NIATx initiative, which received substantial foundation and federal government funding, was essentially an efficacy evaluation. The 23 NIATx agencies represented the top 17% of the applicants selected based on their demonstrated commitment and/or capacity for organizational change. These agencies received coaching from expert consultants and $100,000 per year each in supplemental funding for quality improvement and participated in regular coaching calls and conferences around best practices. The NIATx goal of improving client retention in substance abuse treatment was similar to the enhanced profiling objective of increasing the rate of connect-to-care. Under NIATx, 87% of the agencies implemented rapid “change cycles” with initiatives similar to those recommended for enhanced profiling to increase client retention. NIATx improved early retention of clients (from their first through the third unit of care) significantly (from 62% to 73%). This favorable result was likely due to NIATx’s better resourced and more intensive intervention and its different study design. NIATx compared volunteer agencies before and after participation whereas enhanced profiling used a randomized design. This comparison between enhanced profiling and NIATx suggests that staff time, intensive training, and organizational leadership seem to be a necessary condition to change the mediating variables of providers implementing retention strategies (McCarty et al. 2007).

Despite this short term success, NIATx clients’ improvements failed to reach statistical significance on longer term retention (through the fourth unit of care). The NIATx evaluation noted the challenges in improving longer term retention and its dependence on multiple variables (McCarty et al. 2007). Echoing the NIATx evaluation, we expect that improving long term retention or connect-to-care likely requires addressing the multiple “facets” that affect these measures.

As agency profiles remained private and the regional managers, providers and staff did not receive any tangible incentives, we speculate that the intervention had neither the scope nor the incentive to stimulate favorable changes in clinical practice. In 2009, DMHAS replaced enhanced and basic profiles with semi-annual agency report cards. Beginning in 2011, DMHAS plans to post these on its website. As policy makers choose quality initiatives within the constraints of limited resources, it is important to examine both successes and failures.

It should be noted that programs varied in terms of size, location, staffing, case mix, ownership, vertical integration, proximity to other providers and other variables. Some external factors (e.g., vertical integration, with residential and outpatient programs on the same site) may have increased a program’s ability to transit clients to a lower level of care. Other factors, such as high staff turnover and fewer personal connections among counselors, could constrain all facilities. Some factors vary with level of care. In Connecticut, there were no capacity constraints on outpatient care, but other systems might face such constraints. The randomized design is a strength of this evaluation, because program’s advantages and obstacles would be equally present in the enhanced and basic groups.

The literature on outcomes research has identified a variety of evidence-based practices to improve continuity of care that could be alternatives or supplements to enhanced profiling. These approaches include motivational interviewing, contingency contracting, monitoring and early re-intervention, recovery management checkups, assertive continuing care and the use of contracts and incentives, prompts and social reinforcement. Telephone-based continuing care and internet-based continuing care are proving effective for expanding access to treatment for many previously underserved and hard to reach groups (Dennis and Scott 2007; Horgan et al. 2007; McKay et al. 2005; McKay 2009; Miller et al. 2006; Petry et al. 2002; Shepard et al. 2006; Simon et al. 2000; Strecher 2007; Weingardt et al. 2006). Like the NIATx previous work on coaching (McCarty et al. 2007), these evidence-based practices generally had external research support.

This study has demonstrated some capacity of public officials to serve as coaches to programs on top of their existing responsibilities. This design meant, however, that four layers existed between the policy of enhanced profiling and additional effective client services. First, DMHAS leadership spoke to DMHAS regional staff. Second, DMHAS regional staff visited program administrators. Third, program administrators communicated with program counselors. Fourth, program counselors delivered additional reminders and handoffs to their clients. Incomplete communications among any of these layers could undermine the profiling intervention. Furthermore, no mechanisms were set up to reinforce these exchanges. DMHAS staff were not commended for outstanding coaching nor penalized for low levels of coaching, and the profiles did not praise specific counselors for individual handoffs. In addition, because this application of profiling was based on dichotomous indicators, there was substantial variability in performance from one quarter year to the next. Performance measures that use continuous measures, such as the number of days to connect to a lower level of care, may reduce this random variation. Measurable improvements in outcomes of substance abuse treatment are likely to require more intensive and sustained application of chosen interventions than achieved here, more sensitive indicators, and likely a combination of evidence-based approaches.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported through the Brandeis/Harvard NIDA Center, #P50 DA010233, from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation under grant 65777 from its Substance Abuse Policy Research Program. The authors would like to thank Paul DiLeo, Linda Frisman, Thomas Kirk, Mark McAndrew, and Sue Tharnish of Connecticut’s DMHAS and Debbie O’Coin of Advanced Behavioral Health for their valuable contributions and ongoing support to the project. The authors also thank Clare L. Hurley for editorial assistance and Stephen Moss for assistance with coaching suggestions and training. Finally, the authors would like to acknowledge all the treatment professionals at DMHAS who contributed to the enhanced profiling experiment, including the regional managers and monitors, the treatment providers, the agency directors and the clinical staff for their expertise, support and cooperation.

Contributor Information

Marilyn Daley, Schneider Institutes for Health Policy, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, MS035, Brandeis University, P.O. Box 9110, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454-9110, USA.

Donald S. Shepard, Email: shepard@brandeis.edu, Schneider Institutes for Health Policy, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, MS035, Brandeis University, P.O. Box 9110, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454-9110, USA

Christopher Tompkins, Schneider Institutes for Health Policy, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, MS035, Brandeis University, P.O. Box 9110, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454-9110, USA.

Robert Dunigan, Schneider Institutes for Health Policy, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, MS035, Brandeis University, P.O. Box 9110, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454-9110, USA.

Sharon Reif, Schneider Institutes for Health Policy, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, MS035, Brandeis University, P.O. Box 9110, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454-9110, USA.

Jennifer Perloff, Schneider Institutes for Health Policy, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, MS035, Brandeis University, P.O. Box 9110, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454-9110, USA.

Lauren Siembab, Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, 410 Capitol Avenue, Hartford, CT 06134, USA.

Constance Horgan, Schneider Institutes for Health Policy, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, MS035, Brandeis University, P.O. Box 9110, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454-9110, USA.

References

- Axt-Adam P, van der Wouden JC, van der Does E. Influencing behavior of physicians ordering laboratory tests: A literature study. Medical Care. 1993;31:784–794. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199309000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balas E, Boren SA, Brown GD, Ewigman BG, Mitchell JA, Perkoff GT. Effect of physician profiling on utilization: Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1996;11:584–590. doi: 10.1007/BF02599025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett PG, Swindle RW. Cost-effectiveness of inpatient substance abuse treatment. Health Services Research. 1997;32:615–629. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley M, Shepard DS, Reif S, Dunigan R, Tompkins C, Perloff J, et al. Evaluation of provider profiling in the public sector. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2010;28(4) [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Scott CK. Managing addiction as a chronic condition. Addiction Science and Clinical Practice. 2007;4:45–55. doi: 10.1151/ascp074145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring. Vol. 3. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press; 1985. Methods and findings of quality assessment and monitoring: An illustrated analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Dziuban SW, McIlduff JB, Miller SJ, Dal Col RH. How a New York cardiac surgery program uses outcomes data. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1994;58:1871–1876. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)91730-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy DM. Performance measurement: problems and solutions. Health Affairs. 1998;17(4):7–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney JW, Willenbring ML, Moos RH. Improving the quality of VA care for patients with substance use disorders. Medical Care. 2000;38(6 supplement):I105–I113. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200006001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn L, Zieman GL, Kramer TL, Daniels AS, Lunghofer LA, Hughes R, et al. Measuring treatment effectiveness: Part one: Newly emerging outcomes databases for organizations. Behavioral Healthcare Tomorrow. 1997;6:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy R, Eccles MP, Jamtvedt J, Young JM, Grimshaw JM, Baker R. What do we know about how to do audit and feedback? Pitfalls in applying evidence from a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research. 2005;5:50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, D’Aunno TA, Jin L, Alexander JA. Medical and psychosocial services in drug abuse treatment: Do stronger linkages promote client utilization? Health Services Research. 2000;35:443–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung CH, Lim YW, Mattke S, Damberg C, Shekelle PG. Systematic review: The evidence that publishing patient care performance data improves quality of care. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148:111–123. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnick DW, Lee MT, Horgan CM, Acevedo A. Adapting Washington Circle performance measures for public sector substance abuse treatment systems. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:265–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghali WA, Ash AS, Hall RE, Moskowitz MA. Improving the outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery in New York State. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277:379–382. [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Bero L, et al. Changing provider behavior: An overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Medical Care. 2001;39(8):II-2–II-45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagland M. Provider profiling. Healthplan. 1998;39:32–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AHS, McKellar JD, Moos RH, Schaefer JA, Cronkite RA. Predictors of engagement in continuing care after substance use disorder treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgan CM, Merrick EL, Reif S, Stewart M. Internet based behavioral health services in health plans. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:307–308. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang IC, Dominici F, Frangakis C, Diette GB, Damberg CL, Wu AW. Is risk-adjustor selection more important than statistical approach for provider profiling? Asthma as an example. Medical Decision Making. 2005;25:20–34. doi: 10.1177/0272989X04273138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Improving the quality of health care for mental health and substance-use conditions. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2006a. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Performance measurement: Accelerating improvement. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2006b. [Google Scholar]

- Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristofferson DT, O’Brien MA, Oxman AD. Audit and feedback: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. 2006 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub2. Retrieved from Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Art. No. CD000259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi MS, Bernard DB. Classic CQI integrated with comprehensive disease management as a model for performance improvement. Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement. 1999;25(8):383–395. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazandjian VA, Lied TR. Caesarian section rates: Effects of participation in a performance measurement project. Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement. 1998;24(4):187–196. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizer KW, Demakis JG, Feussner JR. Reinventing VA health care: systematizing quality improvement and quality innovation. Medical Care. 2000;38(Suppl 6):I-7–I-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumholz HM, Brindis RG, Brush JE, Cohen DJ, Epstein AJ, Furie K, et al. Standards for statistical models used for public reporting of health outcomes: An American Heart Association scientific statement from the quality of care outcomes group. Circulation. 2006;113:456–462. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.170769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark H, Garet DE. Interpreting profiling data in behavioral health care for a continuous quality improvement cycle. Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement. 1997;23:521–528. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Hall W. Are detoxification programmes effective? Lancet. 1996;347:97–100. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty D, Gustafson DH, Wisdom JP, Ford J, Dongseok C, Molfenter T, et al. The network for the improvement of addiction treatment (NIATx): Enhancing access and retention. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCorry F, Garnick DW, Bartlett J, Cotter F, Chalk M. Improving performance measurement for alcohol and other drug services: Report of the Washington Circle Group, prepared for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Waltham, MA: Schneider Institutes for Health Policy, Brandeis University; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348:2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR. Effectiveness of continuing care interventions for substance abusers: Implications for the study of long-term treatment effects. Evaluation Review. 2001;25:211–231. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0102500205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR. Is there a case for extended interventions for alcohol and drug use disorders? Addiction. 2005;100:1594–1610. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR. Continuing care research: What we have learned and where we are going. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:131–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Lynch KG, Shepard DS, Pettinati HM. The effectiveness of telephone based continuing care for alcohol and cocaine dependence: 24 month outcomes. Archives General Psychiatry. 2005;62:199–207. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens JR, Weisner CM, Ray GT. Readmission among chemical dependency patients in private, outpatient treatment: Patterns, correlates and role in long-term outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:842–847. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Sorenson JL, Selzer JA, Brigham GS. Disseminating evidence based practices in substance abuse treatment: A review with suggestions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan R, Tikoo M, Capela S, Bernstein DJ. Increasing evaluation use among policymakers through performance measurement. New Directions for Evaluation. 2006;112:89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Long term influence of duration and intensity of treatment on previously untreated individuals with alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2003;98(3):325–327. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugford M, Banfield P, O’Hanlon M. Effects of feedback of information on clinical practice: A review. British Medical Journal. 1991;303:398–402. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6799.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Quality Forum. National voluntary consensus standards for the treatment of substance use conditions: Evidence based treatment practices. Washington, DC: NQF; 2007. [accessed June 23, 2009]. web: www.qualityforum.org. [Google Scholar]

- Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment. [accessed June 26, 2009];NIATx website. 2009 www.niatx.net.

- O’Reilly KB. Study questions impact of quality report cards. American Medical News; 2008. Feb 18, amednews.com. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Applied Studies (OAS) DHHS publication No. SMA 04–3967. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005. Treatment episode data set (TEDS) 2002: Discharges from substance abuse treatment services. [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney JL, Kanzler JR. Low cost contingency management for treatment to opioid and cocaine dependent patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;70:398–405. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer JA, Cronkite R, Ingudomnukul E. Assessing continuity of care practices in substance use disorder treatment programs. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:513–520. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer JA, Harris AHS, Cronkite RC, Turrubiartes P. Treatment staff’s continuity of care practices, patients’ engagement in continuing care, and abstinence following outpatient substance-use disorder treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:747–756. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard DS, Adams T. Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, Survey of treatment providers: Attitudes toward quality improvement practices. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, Schneider Institutes for Health Policy; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard DS, Calabro JAB, Love CT, McKay JR, Tetreault J, Yeom HS. Counselor incentives to improve client retention in an outpatient substance abuse treatment program. Administration and Policy In Mental Health. 2006;33:629–635. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon SR, Soumerai SB. Failure of internet-based audit and feedback to improve quality of care delivered by primary care residents. International Journal of Quality in Health Care. 2005;17:427–431. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, VonKorff M, Rutter C, Wagner E. Randomized trial of monitoring, feedback and management of care by telephone to improve treatment of depression in primary care. British Medical Journal. 2000;320:550–554. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecher V. Internet methods for delivering behavioral health care and health-related interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:53–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. DHHS Publication Number SMA 04–3964. NSDUH Series H-25. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. Results from the 2003 National Survey of Drug Use and Health: National Findings. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur NM, Hoff RA, Druss B, Catalanotto J. Using recidivism rates as a quality indicator for substance abuse treatment programs. Psychiatric Services. 1998;49:1347–1352. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.10.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingardt KR, Villafranca SW, Levin C. Technology based training in cognitive behavior therapy for substance abuse counselors. Substance Abuse. 2006;27:19–25. doi: 10.1300/J465v27n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisdom JP, Ford JH, Hayes RA, Edmundson E, Hoffman K, McCarty D. Addiction treatment agencies’ use of data: A qualitative assessment. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research. 2006;33:394–407. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wones RG. Failure of low-cost audit and feedback to reduce lab test utilization. Medical Care. 1987;25:78–82. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198701000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]