Abstract

Introduction

We examined race/ethnic differences in treatment-related job loss and the financial impact of treatment-related job loss, in a population-based sample of women diagnosed with breast cancer.

Methods

Three thousand two hundred fifty two women with non-metastatic breast cancer diagnosed (August 2005–February 2007) within the Los Angeles County and Detroit Metropolitan Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results registries, were identified and asked to complete a survey (mean time from diagnosis = 8.9 months). Latina and African American women were over-sampled (n = 2268, eligible response rate 72.1%).

Results

One thousand one hundred eleven women (69.6%) of working age (<65 years) were working for pay at time of diagnosis. Of these women, 10.4% (24.1% Latina, 10.1% African American, 6.9% White, p < 0.001) reported that they lost or quit their job since diagnosis due to breast cancer or its treatment (defined as job loss). Latina women were more likely to experience job loss compared to White women (OR = 2.0, p = 0.013)), independent of sociodemographic factors. There were no significant differences in job loss between African American and White women, independent of sociodemographic factors. Additional adjustments for clinical and treatment factors revealed a significant interaction between race/ethnicity and chemotherapy (p = 0.007). Among women who received chemotherapy, Latina women were more likely to lose their job compared to White women (OR = 3.2, p < 0.001), however, there were no significant differences between Latina and White women among those who did not receive chemotherapy. Women who lost their job were more likely to experience financial strain (e.g. difficulty paying bills 27% vs. 11%, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Job loss is a serious consequence of treatment for women with breast cancer. Clinicians and staff need to be aware of aspects of treatment course that place women at higher risk for job loss, especially ethnic minorities receiving chemotherapy.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Survivorship, Employment, Racial/ethnic disparities

Introduction

Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in survivorship outcomes for individuals with cancer is an important research priority. Since over half of women diagnosed with breast cancer are of working age (less than 65 years) at the time of diagnosis, paid work and employment outcomes are a key component of their survivorship [1–3]. Many women diagnosed with breast cancer must undergo a complex and arduous treatment program while negotiating work and family responsibilities. Although some studies suggest that cancer and its treatment does not limit a women’s ability to return to work [1, 2, 4–8], return to work and other work outcomes may vary by race/ethnicity [4].

Racial and ethnic minorities may be vulnerable to poor work outcomes because they are generally diagnosed with more advanced disease [9, 10], require more aggressive treatment course [11–14], and have more co-morbidities [15]. Additionally, Latina and African American women tend to be disproportionately represented in lower paying jobs and unsupportive employment settings [16–18]. Despite these concerns, racial/ethnic variation in work outcomes remain understudied. The few studies that have examined such variation have produced mixed results with some documenting racial/ethnic differences in work outcomes [1] and others finding no differences [8, 19]. These studies have been limited by small samples and a lack of diversity by socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity. Latinas have been particularly under-studied despite their growing proportion among breast cancer survivors [20].

Losing one’s job is perhaps the most severe work-related consequence and may have significant social and economic implications. Several qualitative reports have suggested that patient’s concerns about financial matters influence their decisions to continue paid work during cancer treatment [21–23]. However, few studies have assessed job loss or its financial impact in women with breast cancer [6, 19, 24–26]. To address these issues, we used a multi-ethnic population-based sample of women recently diagnosed with breast cancer in Los Angeles County and Metropolitan Detroit to examine racial/ethnic differences in job loss and patient report of the financial impact. Specifically, we asked: 1) What is the extent of job loss experienced by women diagnosed with breast cancer? 2) Are there racial/ethnic differences in job loss? 3) What clinical and treatment factors might explain racial/ethnic differences in job loss? and 4) Is job loss associated with financial strain?

Patients and methods

Study population

Our study sample consisted of women who were residents of Los Angeles and County and Metropolitan Detroit between June 2005 and February 2007. Eligibility criteria included: 1) 20–79 years of age, 2) a primary diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in-situ or invasive breast cancer (American Joint commission on Cancer Stage I–III) [27], and 3) ability to complete a questionnaire in English or Spanish. We excluded patients who died prior to the survey in addition to Asian women in Los Angeles because these women were already being enrolled in other studies. African American women in both regions were over-sampled as well as Latinas in Los Angeles.

Sampling and data collection

Eligible patients were identified via rapid case ascertainment as they were reported to the Los Angeles Cancer Surveillance Program (LACSP) and the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System (MDCSS)—the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program registries for the metropolitan areas of Los Angeles, California and Detroit, Michigan. In both regions, we selected all African American women based on demographic information from the treating hospitals. Because Latina status is often inaccurately reported by the treating hospitals, we used a surname-based sampling strategy to increase the representation of Los Angeles resident Latina women in the study, an approach validated by our research team [28]. After selecting these racial/ethnic subgroups, we selected an approximate one-third random sample of the remaining white (non-Spanish surnamed) patients from both regions.

After physician notification, we mailed an introductory letter, survey materials, and a $10 cash gift to eligible subjects. The patient survey was translated into Spanish using a standard approach [29] and distributed to patients in LA who were likely to be Latina. The Spanish version was not made available to Detroit subjects because there are very few monolingual Spanish speaking patients in the metropolitan Detroit area. A modified version of the Dillman survey method was employed to encourage survey response including: 1) a postcard reminder to non-respondents at 2 weeks, 2) a second letter and survey at 6 weeks, and 3) a follow-up phone call at 10 weeks [30]. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Michigan, the University of Southern California, and Wayne State University.

Of the 3252 eligible patients who were identified for selection, 119 were excluded because they were too ill, did not speak English or Spanish, denied having cancer, or their physician refused contact. Study materials were then sent to the remaining 3133 patients, however 432 (13.8%) could not be contacted, 411 (13.1%) patients were contacted but did not participate in the survey, and 22 (0.7%) completed the survey but this information could not be merged to SEER data. Thus, 2268 (72.4% overall; 72.4% for Hispanics; 65.8% for African Americans; and 75.4% for whites) were included in the final analytic sample (96.5% of whom completed a self-administered questionnaire and 3.5% completed a telephone survey).

The survey information was merged to SEER data for patients in the final sample. An analysis of non-respondents versus respondents showed that there were no significant differences by age at diagnosis or Hispanic ethnicity. However, compared to respondents, non-respondents were more likely to be African American (34.9% vs. 26.2%, p < .001), to have never married (23.0% vs. 19.3%, p = .010), to have stage II or III disease (43.4% vs. 40.5%, p = .005), and to have received a mastectomy (45.4% vs. 36.8%, p = 0.020).

Study measures

The main dependent variable for this study was job loss after diagnosis of breast cancer. Job loss was defined from two separate questions from the patient survey. Women were asked if they quit or lost their job since diagnosis due to breast cancer or its treatment (each with yes/no response options). We combined reports of quitting and losing the job to create an overall measure of job loss because: 1) the distribution of quitting and losing the job was similar (4.3% quit; 5.5% lost; 0.6% reported both; 89.6% reported neither) and 2) multivariable models (with quitting vs. losing the job as separate dependent variables) produced comparable results in terms of both the direction and magnitude of associations. Although we did not collect information on the exact timing of job loss, we did ask women if they were working during breast cancer treatment (yes/no).

An additional dependent variable was patient perceptions regarding the financial strain of breast cancer. Women were asked to indicate whether or not (yes/no) breast cancer diagnosis or treatments resulted in various dimensions of financial strain including: facing an inability to pay bills, having to use savings, or to cut down on spending for a variety of things (food and/or clothes, health care for other family members, children activities recreational activities, or household items. We also asked women to report the average number of hours worked per week (full-time ≥35; part-time <35 h). To characterize employment support, we asked women if either paid sick leave or a flexible work schedule was available through their employer or work at time of diagnosis (each with a yes/no response option). We created an employment support variable to indicate if women had none (neither paid sick leave nor flexible work schedule), one (either paid sick leave or flexible work schedule) or two (both paid sick leave and flexible work schedule) sources of employment support.

Information was also collected on sociodemographic and treatment factors via questionnaire. Sociodemographic factors included study site, age at the time of diagnosis, race/ethnicity, education, income, number supported by family income, marital status, and time from breast cancer diagnosis to survey completion. Treatment factors included first surgical procedure, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. Clinical factors were taken from the SEER record and patient report and included breast cancer stage at diagnosis (using American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM Staging System for breast cancer) [27], and patient reported number of co-morbidities (chronic bronchitis/emphysema, heart disease, other cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, stroke, arthritis).

Statistical analysis

The analytic sample was restricted to women of working age (<65 years, n = 1595) who were working at the time of breast cancer diagnosis (n = 1111, 69.6%). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the distribution of the study variables overall and by race/ethnicity. Population weights were included in all analyses to account for differential selection by race, ethnicity, and non-response. For each racial/ethnic group we calculated site-specific (Los Angeles; Detroit) weights as the inverse of the number of patients in our sample divided by the number of that race/ethnic group in the population (defined by the SEER registry).

Bivariate associations between job loss and each of the independent variables were tested using Wald’s Chi-square test. To determine the factors that may explain any observed racial/ethnic differences in job loss based on bivariate associations, we ran a series of logistic regression models to adjust for potential confounders and mediators. Model 1 estimated the odds of job loss by race/ethnicity, independent of study site, age at diagnosis, and time since breast cancer diagnosis. Model 2 additionally controlled for other sociodemographic confounding factors and potential mediating factors were added in Model 3 (clinical and treatment factors).

Based on prior research, [25] we examined the interplay between race/ethnicity, chemotherapy, and employment support (paid sick leave/flexible work schedule) in relation to job loss. In Model 3, we tested all two interactions between race/ethnicity, receipt of chemotherapy, and employment support factors as well as the three way interaction. Statistically significant interactions (p < 0.05) were retained in final models. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1.3 programming language.

Results

Three quarters (75.5%) were working full-time at the time of breast cancer diagnosis and 24.5% were working part-time; the mean age was 50.8 (SD = 7.8); and 16.5%, 15.5%, and 68.0% were Latina, African American, and White respectively (Table 1). The majority of women were married (61.6%), had no co-morbidities (56.3%), received a lumpectomy (71.6%), radiation therapy (70.7%), and chemotherapy (54.5%). Among women receiving chemotherapy, 64.8% of women had completed treatment and 63.9% of women receiving radiation therapy had also completed treatment (not shown in Table 1). More than half of women had paid sick leave (54.6%) or a flexible work schedule (61.5%) available at the time of diagnosis and 40.5% of women had both (Table 1). The mean time from diagnosis to survey completion was 8.9 months (range: 1 month–26 months).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics overall and by race/ethnicity (N = 1111)

| N | Overall | Latina (N = 278) | African American (N = 304) | White (N = 497) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %weighted | % weighted | % weighted | % weighted | |||

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||||

| Site | ||||||

| Detroit | 513 | 28.2 | 2.6 | 36.6 | 31.0 | <0.001 |

| Los Angeles | 598 | 71.8 | 97.4 | 63.4 | 69.0 | |

| Age | ||||||

| <45 | 239 | 19.7 | 28.8 | 25.7 | 16.3 | <0.001 |

| 45–54 | 472 | 42.0 | 41.7 | 36.5 | 43.0 | |

| 55–64 | 400 | 38.3 | 29.5 | 37.8 | 40.7 | |

| Education | ||||||

| H.S diploma or less | 305 | 29.2 | 53.6 | 17.1 | 15.7 | <0.001 |

| Some college | 426 | 40.7 | 31.1 | 48.4 | 41.8 | |

| College graduate and beyond | 369 | 30.1 | 15.3 | 34.5 | 42.5 | |

| Family income | ||||||

| unknown | 118 | 9.8 | 18.0 | 6.6 | 8.6 | <0.001 |

| <$30,000 | 230 | 15.9 | 36.7 | 24.7 | 8.8 | |

| $30,000–$59,999 | 289 | 24.3 | 23.0 | 33.2 | 22.5 | |

| $60,000+ | 474 | 50.0 | 22.3 | 35.5 | 60.1 | |

| Number supported by family income | ||||||

| 1 | 270 | 25.0 | 19.5 | 32.4 | 24.5 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 371 | 35.0 | 30.0 | 31.7 | 36.8 | |

| 3+ | 448 | 40.0 | 50.5 | 35.9 | 38.7 | |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Full-time | 785 | 75.5 | 74.2 | 82.2 | 74.4 | 0.038 |

| Part-time | 248 | 24.5 | 25.8 | 17.8 | 25.6 | |

| Paid sick leave | ||||||

| Yes | 589 | 54.5 | 37.8 | 61.8 | 57.5 | <0.001 |

| No | 522 | 45.4 | 62.2 | 38.2 | 42.5 | |

| Flexible work schedule | ||||||

| Yes | 642 | 61.5 | 47.2 | 49.3 | 68.0 | <0.001 |

| No | 469 | 38.5 | 52.8 | 50.7 | 32.0 | |

| Employment support (paid leave/flexible schedule)a | ||||||

| None | 297 | 24.4 | 41.7 | 26.4 | 19.5 | <0.001 |

| Only one | 397 | 35.1 | 31.7 | 36.2 | 35.4 | |

| Both | 417 | 40.5 | 26.6 | 37.4 | 45.1 | |

| Married/domestic partner | ||||||

| Yes | 656 | 61.6 | 63.9 | 40.7 | 65.6 | <0.001 |

| No | 444 | 38.4 | 36.1 | 59.3 | 34.4 | |

| Time from diagnosis (months)b | 1090 | 9.1 (6.0) | 10.4 | 8.9 | 8.9 | <0.001 |

| Clinical/treatment factors | ||||||

| Number of co-morbidities | ||||||

| 0 | 607 | 56.3 | 64.0 | 45.1 | 57.2 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 314 | 28.2 | 25.2 | 30.0 | 28.6 | |

| 2+ | 190 | 15.5 | 10.8 | 24.9 | 14.2 | |

| Stage | ||||||

| 0 | 218 | 20.9 | 19.4 | 21.2 | 21.3 | 0.282 |

| I | 366 | 33.8 | 29.9 | 30.2 | 35.3 | |

| II | 379 | 31.8 | 37.1 | 36.5 | 29.4 | |

| III | 141 | 13.5 | 13.6 | 12.1 | 14.0 | |

| Surgical procedure | ||||||

| Lumpectomy | 758 | 71.6 | 66.2 | 74.7 | 72.3 | 0.137 |

| Mastectomy | 318 | 28.4 | 33.8 | 25.3 | 27.7 | |

| Radiation therapy | ||||||

| Yes | 769 | 70.7 | 63.7 | 72.4 | 71.7 | 0.021 |

| No | 320 | 29.3 | 36.3 | 27.6 | 28.3 | |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| Yes | 646 | 54.5 | 66.5 | 55.8 | 51.5 | 0.005 |

| No | 465 | 45.5 | 33.5 | 44.2 | 48.5 | |

| Study outcome | ||||||

| Job loss | ||||||

| Yes | 144 | 10.4 | 24.1 | 10.1 | 6.9 | <0.001 |

| No | 967 | 89.6 | 75.9 | 89.9 | 93.1 | |

N = 32 other race/ethnicity were excluded due to limited sample size <2% missing on all covariates

Percents are weighted to account for differential selection by race/ethnicity, and non-response

aone refers to either flexible work schedule or paid sick leave available through employer

And both refers to both paid sick leave and flexible work schedule available

bmeans (standard deviation) reported

p-value for chi-square test of overall significance

Job loss after diagnosis (quitting or losing one’s job) was reported by 10.4% of working women and among these women, 84.6% did not work during breast cancer treatment. Job loss was associated with race/ethnicity in bivariate analyses (p < 0.001). Latina women had the highest prevalence of job loss followed by African American and White women (24.1%, 10.1%, and 6.9% respectively). There was also racial/ethnic variation in all sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment factors (excluding breast cancer stage at diagnosis and surgical procedure). African American women were most likely to have two or more co-morbidities and least likely to be married. Latinas had the lowest levels of education and income, were most likely to receive chemotherapy, and least likely to have paid sick leave or a flexible work schedule available through work.

Table 2 shows the adjusted odds ratios of job loss by categories of race/ethnicity controlling for sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment factors. In initial models adjusted for study site, age, and time from breast cancer diagnosis. (Model 1), the relative odds of job loss (as compared to Whites) was 4.3 [95% C.I.: 2.6–7.0] for Latinas. There were no significant differences in job loss between African American and White women in Model 1 (OR, 95% C.I. 1.5 [0.9–2.8]). When additional sociodemographic factors (education, income, number supported by family income, marital status, and paid sick leave and/or flexible work schedule) were included, the relative odds of job loss (as compared to Whites) were substantively reduced to 2.2 [95% C.I: 1.2–4.1] for Latinas and remained statistically insignificant for African Americans. In final models (Model 3) adjusting for treatment and clinical factors, we found a statistically significant interaction between race/ethnicity and receipt of chemotherapy (p = 0.007). The relative odds of job loss (as compared to Whites) was 3.8 [95% C.I: 1.7–8.2) for Latinas and 1.3 [95% C.I.: 0.5–3.3] for African Americans, among women who received chemotherapy. However, there were no significant differences between Latinas and Whites (OR = 0.5, 95% C.I: 0.1–1.7) or African Americans and Whites (OR = 0.3, 95% C.I.: 0.1–1.3) among women who did not receive chemotherapy. In final models, the number of co-morbidities, and employment support (paid sick leave/flexible work schedule) were also significantly associated with job loss. Women with two or more co-morbidities were more likely to experience job loss when compared to women with none (OR = 2.5 [95% C.I.:1.3–4.9]). Women who did not have employment support (neither paid sick leave nor flexible work schedule) and women who had only one source of employment support were more likely to experience job loss as compared to women who had both sources of support (OR = 7.3 [95% C.I: 3.6–14.9 for no source of support; OR = 2.4 [95% C.I.: 1.1–4.9] for one source of support).

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratio [95% C.I] of job loss by sociodemographic, and clinical/treatment factors

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site | |||

| Detroit | 1.2 [0.7–2.0] | 1.3 [0.7–2.3] | 1.1 [0.6–2.0] |

| Los Angeles | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Age | |||

| <45 | 1.0 [0.6–1.7] | 1.1 [0.6–2.0] | 1.1 [0.5–2.3] |

| 45–54 | 0.9 [0.6–1.4] | 1.0 [0.6–1.7] | 1.1 [0.6–2.0] |

| 55–64 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Χ 2 p-value | 0.892 | 0.970 | 0.933 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Latina | 4.3 [2.6–7.0] | 2.2 [1.2–4.1] | N/A |

| African American | 1.5 [0.9–2.8] | 0.9 [0.4–1.7] | |

| White | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Χ 2 p-value | <0.001 | 0.024 | 0.401 |

| Education | |||

| H.S diploma or less | 1.1 [0.6–2.3] | 1.2 [0.6–2.6] | |

| Some College | 1.1 [0.6–1.9] | 1.1 [0.6–2.0] | |

| College graduate and beyond | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Χ 2 p-value | 0.935 | 0.880 | |

| Income | |||

| Unknown | 1.4 [0.6–3.0] | 1.6 [0.7–3.7] | |

| <$30,000 | 1.6 [0.8–3.3] | 1.3 [0.6–3.0] | |

| $30,000–$59,999 | 0.7 [0.4–1.5] | 0.6 [0.3–1.2] | |

| ≥$60,000 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Χ 2 p-value | 0.160 | 0.101 | |

| Employment status | |||

| Full-time | 1.2 [0.7–2.0] | 1.2 [0.7–2.1] | |

| Part-time | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Employment support (paid leave/flexible schedule)a | |||

| None | 7.5 [3.9–14.5] | 7.3 [3.6–14.9] | |

| Only One | 2.3 [1.1–4.5] | 2.4 [1.1–4.9] | |

| Both | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Χ 2 p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Married/domestic partner | |||

| Yes | 0.8 [0.4–1.4] | 0.9 [0.4–1.6] | |

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Stage at diagnosis | |||

| 0/I | 1.0 [0.5–2.0] | ||

| II/III | 1.0 | ||

| Number of co-morbidities | |||

| 2+ | 2.5 [1.3–4.9] | ||

| 1 | 0.7 [0.4–1.3] | ||

| 0 | 1.0 | ||

| Χ 2 p-value | 0.003 | ||

| Surgical procedure | |||

| Mastectomy | 1.5 [0.8–2.7] | ||

| Lumpectomy | 1.0 | ||

| Radiation therapy | |||

| Yes | 0.6 [0.4–1.1] | ||

| No | 1.0 | ||

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Yes | N/A | ||

| No | |||

| Race/Ethnicity by chemotherapy | |||

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Latina | 3.8 [1.7–8.2] | ||

| African American | 1.3 [0.5–3.3] | ||

| White | 1.0 | ||

| No chemotherapy | |||

| Latina | 0.5 [0.1–1.7] | ||

| African American | 0.3 [0.1–1.3] | ||

| White | 1.0 | ||

| Χ 2 p-value for interaction | 0.007 | ||

Model 1: study site, age, race/ethnicity, time from breast cancer diagnosis

Model 2: Model 1+ age, education, income, number supported by income, marital status, full-time employment, employment support (paid leave/flexible schedule);

Model 3: Model 2+ number of co-morbidities, breast cancer stage, surgical procedure, radiation therapy, chemotherapy <2% missing on all covariates

Χ 2represents the p-value for the chi-square test for overall significance between job loss and categorical variables with more than two levels

aone refers to either flexible work schedule or paid sick leave available through employer

And both refers to both paid sick leave and flexible work schedule available

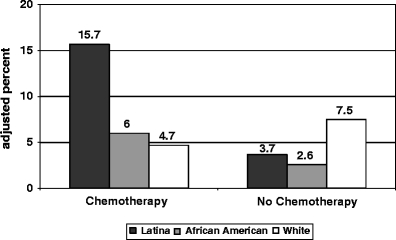

The interaction between race/ethnicity and chemotherapy is further illustrated in Fig. 1. Among women who received chemotherapy, job loss was most prevalent in Latinas with 15.7% reporting job loss as compared to only 6.0% of African American women and 4.7% of White women (independent of sociodemographic, treatment, and clinical factors). However, among women who did not receive chemotherapy, there were minimal differences in job loss across racial/ethnic groups (7.5%, 3.7%, and 2.6% among White, Latina, and African American women respectively) and no statistically significant differences between Latinas and White women or African American and White women. In investigating the interplay between race/ethnicity, receipt of chemotherapy, and employment support (paid sick leave/flexible work schedule), we found no statistically significant interactions between employment support and race/ethnicity or employment support and chemotherapy. The three way interaction between race/ethnicity, employment support, and receipt of chemotherapy was also not statistically significant (all p’s >0.10)

Fig. 1.

Adjusted percent job loss by race/ethnicity and chemotherapy. Model includes: age, race/ethnicity, chemotherapy, race/ethnicity*chemotherapy interaction term, education, family income, number supported by family income, full-time employment, employment support (paid sick leave/flexible work schedule), marital status, time from breast cancer diagnosis, number of co-morbidities, breast cancer stage, surgical procedure, receipt of radiation therapy. p-value for interaction between race/ethnicity and receipt of chemotherapy p = 0.007

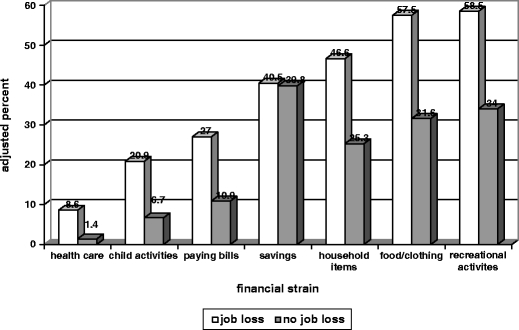

Job loss was highly associated with most financial strain measures (except use of savings) even after adjusting for sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment factors (Fig. 2). Women who experienced job loss compared to women who did not, more often reported that they could not make credit card payments or other bills (27.0% vs. 10.9%), had to cut down on purchasing food and clothing (57.5% vs. 31.6%), and had to cut down on general expenses (76.4% vs. 52.8%). The only racial/ethnic differences in financial strain was for difficulty paying bills (p = 0.005). African American women reported having more difficulty paying bills as compared to Whites after adjusting for sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment related factors (OR [95% C.I.]: 2.2 [1.3–3.6]).

Fig. 2.

Patient report of the financial impact of breast cancer by job loss categories, p-values: savings (p = 0.946); all else (p < 0.001), X-axis represents patient reports of experiencing each type of financial strain. Model adjusts for age, time from initial diagnosis, race/ethnicity, education, income, number supported by income, marital status, breast cancer stage, number of co-morbidities, surgical treatment, receipt of radiation therapy, and receipt of chemotherapy. <2% missing data on all covariate

Discussion

This study examined racial and ethnic differences in treatment-related job loss in a diverse population-based sample of working-aged women recently diagnosed with breast cancer. We found that 10.4% of women who were working for pay at the time of diagnosis reported job loss at the time of survey completion (~9 months after diagnosis). Importantly, there were substantial racial/ethnic differences in job loss in the context of the treatment experience. Among patients who received chemotherapy, Latina women were more likely to lose their job after diagnosis than women of other racial/ethnic groups but this was not observed for women who did not receive chemotherapy. These findings were observed after controlling for sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment factors.

Prior research on paid work outcomes related to breast cancer have generally been reassuring regarding women’s ability to return to work after diagnosis and treatment for breast cancer [1, 2, 4–6, 8, 25]. Yet we are unaware of any studies that have specifically evaluated racial/ethnic differences in treatment-related job loss. Moreover, these studies have been limited by low power and insufficient representation of ethnic minorities. We contribute to a growing body of research on breast cancer and paid work outcomes by focusing on African American and Latina women in a population-based sample with sufficient representation of these women. A previous paper by our research team described patterns and correlates of missed paid work during the breast cancer treatment period in a similar patient sample [25]. Some missed work was commonly observed (24% missed more than 1 month) after diagnosis, and missed work was highly associated with complexity of treatment and level of employment support (paid sick leave/flexible work schedule). African American and Latina women were more likely than Whites to miss more work days as were women who received aggressive treatment (mastectomy and chemotherapy) or were in unsupportive employment settings (no paid sick leave, no flexible work schedule).

In contrast, this analysis showed that treatment-related job loss was much less frequent (10.4%) than missed work. We also found that there was an interaction between race/ethnicity and receipt of chemotherapy such that racial/ethnic differences in job loss were only statistically significant for women who received chemotherapy in fully adjusted models. Latina women within this context were particularly vulnerable to job loss, independent of being in supportive employment settings (having paid sick leave and a flexible work schedule). Latinas may be at particular risk for job loss because they may have more difficulty navigating the health care system and in turn balancing work and treatment [18, 31, 32]. Additionally, this vulnerability may be due to language barriers and unmeasured socioeconomic and employment factors (more isolated work settings, multiple employers, or temporary employment) [31, 32].

Strengths of this study include the use of a multi-ethnic population-based sample. We also obtained information on a comprehensive set of sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment factors. Some limitations to our study also merit comment. Although we have a large study and over-sampled for Latina and African American women, we had limited power to detect small differences in job loss due to the low prevalence of job loss in the study population. Additionally, the cross-sectional design of our study limits inferences on causal relationships between breast cancer treatments on job loss. Patient report of experiences such as job loss and employment accommodations may be subject to recall bias, which may have resulted in an under or over-estimate of experiences with job loss. However, we interviewed women an average of 9 months post cancer diagnosis and we have no apriori reason to believe that recall bias differs by race/ethnicity. Finally, we did not have objective measures of employment support and did not measure a comprehensive set of employment support factors. Some women who lost their jobs may have indicated their employment settings were unsupportive, irrespective of the actual conditions.

Our results have important implications for clinical policy and future research. Because maintaining a healthy and satisfying work life may prevent financial strain and social isolation, doing so is an important issue for many women with a new diagnosis of cancer. Clinicians and staff need to be aware of the potential for job loss especially in ethnic minority breast cancer patients who receive a recommendation for chemotherapy. For these women balancing treatment and work may be particularly difficult even in supportive employment settings. Interventions delivered at the practice-level should encourage clinicians and staff to discuss job demands with patients and offer treatment scheduling options and symptom management strategies to help women balance cancer and work. Future research is needed to examine the long-term consequences of treatment-related job loss across the continuum of care and into the survivorship period.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants R01 CA109696 and R01 CA088370 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to the University of Michigan. Dr. Mujahid was a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health & Society Scholar during the study period. Dr. Katz was supported by an Established Investigator Award in Cancer Prevention, Control, Behavioral, and Population Sciences Research from the NCI (K05CA111340). The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Health Services as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract N01-PC-35136 awarded to the Northern California Cancer Center, contract N01-PC-35139 awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract N02-PC-15105 awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreement #U55/CCR921930 awarded to the Public Health Institute. The collection of metropolitan Detroit cancer incidence data was supported by the NCI SEER Program contract N01-PC-35145. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and endorsement by the State of California, Department of Public Health the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Bouknight RR, Bradley CJ, Luo Z. Correlates of return to work for breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(3):345–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maunsell E, Drolet M, Brisson J, Brisson C, Masse B, Deschenes L. Work situation after breast cancer: results from a population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(24):1813–22. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman B. Cancer survivors at work: a generation of progress. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(5):271–80. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.5.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley CJ, Neumark D, Luo Z, Schenk M. Employment and cancer: findings from a longitudinal study of breast and prostate cancer survivors. Cancer Invest. 2007;25(1):47–54. doi: 10.1080/07357900601130664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drolet M, Maunsell E, Brisson J, Brisson C, Masse B, Deschenes L. Not working 3 years after breast cancer: predictors in a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(33):8305–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drolet M, Maunsell E, Mondor M, Brisson C, Brisson J, Masse B, et al. Work absence after breast cancer diagnosis: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2005;173(7):765–71. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spelten ER, Mirjam AG, Sprangers MA. Factors reported to influence the return to work of cancer survivors: a literature review. Psycho-Oncology. 2002;11(2):124–31. doi: 10.1002/pon.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley CJ, Bednarek HL, Neumark D. Breast cancer and women’s labor supply. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1309–28. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sassi F, Luft HS, Guadagnoli E. Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in female breast cancer: screening rates and stage at diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2165–72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lantz PM, Mujahid M, Schwartz K, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, Salem B, et al. The influence of race, ethnicity, and individual socioeconomic factors on breast cancer stage at diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2173–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hershman D, McBride R, Jacobson JS, Lamerato L, Roberts K, Grann VR, et al. Racial disparities in treatment and survival among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(27):6639–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz SJ, Lantz PM, Paredes Y, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, Liu L, et al. Breast cancer treatment experiences of Latinas in Los Angeles County. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(12):2225–30. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du W, Simon MS. Racial disparities in treatment and survival of women with stage I–III breast cancer at a large academic medical center in metropolitan Detroit. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;91(3):243–8. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-0324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Race, socioeconomic status, and breast cancer treatment and survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(7):490–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.7.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adderley-Kelly B, Williams-Stephens E. The relationship between obesity and breast cancer. ABNF J. 2003;14(3):61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy E, Graff EJ (2005) Getting even: why women don’t get paid like men-and what to do about it. Simon and Schuster

- 17.Reskin BF, Padavic I (2006) Sex, race, and ethnic inequality in United States workplaces. In: Chafetz JS (ed) Handbook of the sociology of gender. Springer

- 18.Browne I (1999) Latinas and African American women at work: race, gender, and economic inequality. Russell Sage Foundation

- 19.Bradley CJ, Oberst K, Schenk M. Absenteeism from work: the experience of employed breast and prostate cancer patients in the months following diagnosis. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15(8):739–47. doi: 10.1002/pon.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ries L, Melbert D, Krapcho M, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Feuer EJ, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2004. National Cancer Institue, Bethesda, MD: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2004/, based on November 2006 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER website, 2007, Contract No.: Document Number|.

- 21.Kennedy F, Haslam C, Munir F, Pryce J. Returning to work following cancer: a qualitative exploratory study into the experience of returning to work following cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2007;16(1):17–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Main DS, Nowels CT, Cavender TA, Etschmaier M, Steiner JF. A qualitative study of work and work return in cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2005;14(11):992–1004. doi: 10.1002/pon.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maunsell E, Brisson C, Dubois L, Lauzier S, Fraser A. Work problems after breast cancer: an exploratory qualitative study. Psychooncology. 1999;8(6):467–73. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199911/12)8:6<467::AID-PON400>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi KS, Kim EJ, Lim JH, Kim SG, Lim MK, Park JG, et al. Job loss and reemployment after a cancer diagnosis in Koreans—a prospective cohort study. Psychooncology. 2007;16(3):205–13. doi: 10.1002/pon.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mujahid MS, Janz NK, Hawley SH, Hamilton AS, Katz SJ. The impact of sociodemographic, treatment, and work support factors on the amount of missed work after breast cancer diagnosis Breast Cancer Res Treat. [In Press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Bradley CJ, Bednarek HL, Neumark D. Breast cancer survival, work, and earnings. J Health Econ. 2002;21(5):757–79. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benson JR, Weaver DL, Mittra I, Hayashi M. The TNM staging system and breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4(1):56–60. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(03)00961-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamilton AS, Hofer TP, Hawley ST, Morrell D, Leventhal M, Deapen D, et al. Latinas and breast cancer outcomes: population-based sampling, ethnic identity and acculturation assessment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2009;7(18):2022–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9(2):183–205. doi: 10.1177/07399863870092005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anema MG, Brown BE. Increasing survey responses using the total design method. J Contin Educ Nurs. 1995;26(3):109–14. doi: 10.3928/0022-0124-19950501-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kraemer J, Wright K, Coscarelli A, et al. Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: a qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2004;13(6):408–28. doi: 10.1002/pon.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla GV, Bohorquez DE, Tejero JS, Garcia M. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Latina women. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2006;24(3):19–52. doi: 10.1300/J077v24n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]