Abstract

Many patients assume that allergic reactions against foods are responsible for triggering or worsening their allergic symptoms. Therefore, it is important to identify patients who would benefit from an elimination diet, while avoiding unnecessary dietary restrictions. The diagnosis of food allergy depends on the thorough review of the patients's medical history, results of supplemented trials of dietary elimination, and in vivo and in vitro tests for measuring specific IgE levels. However, in some cases the reliability of such procedures is suboptimal. Oral food challenges are procedures employed for making an accurate diagnosis of immediate and occasionally delayed adverse reactions to foods. The timing and type of the challenge, preparation of patients, foods to be tested, and dosing schedule should be determined on the basis of the patient's history, age, and experience. Although double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges(DBPCFC) are used to establish definitively if a food is the cause of adverse reactions, they are time-consuming, expensive and troublesome for physician and patients. In practice, An open challenge controlled by trained personnel is sufficient especially in infants and young children. The interpretation of the results and follow-up after a challenge are also important. Since theses challenges are relatively safe and informative, controlled oral food challenges could become the measure of choice in children.

Keywords: Oral food challenge, Food allergy, Child

Introduction

Adverse reactions to food are among the most common complaints in children. However, only 2-4% of these reactions can be attributed to reproducible, IgE-mediated food allergies1). Atopic dermatitis (AD) is commonly associated with a food allergy2). Gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms may also be caused by a food allergy.

The diagnostic work-up of a suspected food allergy includes the patient's history, a skin-prick test (SPT)3), measurement of food-specific IgE antibodies using serologic assays4), and, more recently, the atopy patch test5).

Since the introduction of oral food challenges (OFCs) in clinical practice, double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges (DBPCFCs) have been used to definitively establish whether a food is the cause of adverse reactions. However, DBPCFCs are time-consuming, expensive, and troublesome for physicians and patients. An open challenge controlled by trained personnel is sufficient, especially in infants and young children6). This review covers the indications, the practical performance (including preparation and dosing), and the interpretation of OFCs.

Indications for OFCs

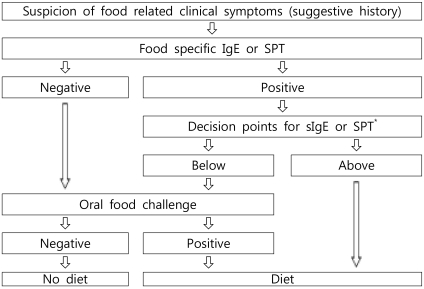

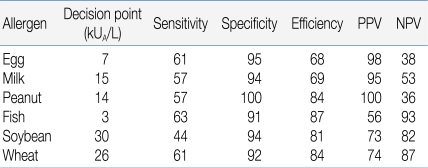

An OFC should be performed for establishment or exclusion of a diagnosis, for scientific purposes in clinical trials, or for the determination of the threshold value or the allergenicity of foods. Fig. 1 provides an algorithm for proceeding from the suspicion of food-related symptoms to the final decision for recommending a specific therapeutic elimination diet. The process includes the measurement of specific IgE levels or an SPT in the decision-making process6, 7). Diagnostic decision points for specific IgE, with a 90% predictive probability for 4 major food allergens, have been described by Sampson et al. (Table 1)4). However, predictive decision points vary remarkably among authors and the studied population8). Therefore, decision points must be studied for each food allergen in the target population. These efforts may help avoid unnecessary OFCs.

Fig. 1.

How to proceed from the suspicion of food-repeated symptoms to the final decision on recommending a therapeutic specific elimination diet. *Diagnostic decision points appear to be population, age, and allergen dependent.

Table 1.

Performance Characteristics of 90% Specificity Diagnostic Decision Points Generated in a Retrospective Study13) in Diagnosing Food Allergy in 100 Consecutive Children and Adolescents Referred for Evaluation of Food Hypersensitivity

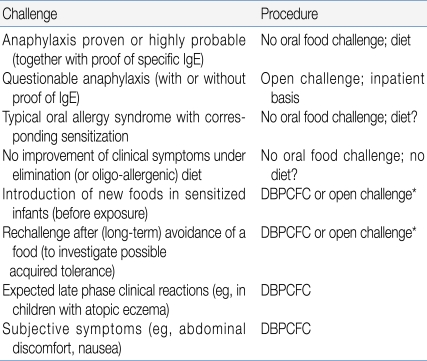

Types of OFC

There has been a debate about whether OFCs should be done in an open or double-blind fashion. In an open OFC, the food is given in its natural form. For a single-blind OFC, the food or placebo is given in a vehicle that disguises the appearance and the taste of the food. The patient is unaware of the nature of the food given, whereas staff involved in the procedure have this information. For DBPCFCs, none of the parties involved is aware of the composition of the product. Placebo challenges are indicated if day-to-day variation plays a major role in symptoms, for example in children with AD, or in cases where there are subjective symptoms such as abdominal discomfort, a burning sensation on the tongue, or palpitations9, 10). Common clinical indications for OFC and the corresponding procedures are shown in Table 210). Although DBPCFC is generally the preferred scientific research protocol, open challenge may be indicated in infants and children younger than 3 years of age, according to a review by the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology11).

Table 2.

Clinical Indications for Oral Food Challenges and the Corresponding Procedures

*Depending on type of symptoms (eg, presence of atopic eczema).

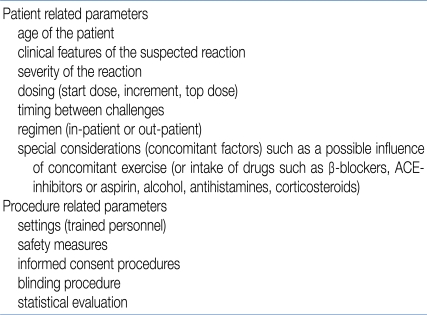

Preparation for OFC

There are several issues to be considered prior to an OFC in patients. These can be divided into patient-related and procedure-related parameters (Table 3)11).

Table 3.

Several Issues to be Determined Prior to Commencing a food Challenge in a Patient

1. Settings

The OFC should be designed and carried out by experienced health care professionals in a facility where the challenge can be closely monitored and measures for the treatment of potential life-threatening reactions are available. Hospital admission or, occasionally, the intensive care unit, may be necessary in certain cases12). The timing, type, and severity of expected symptoms may influence the selection of the OFC location13).

2. Food preparation

Food for an open OFC can be brought from home by the patient or parent, whereas for a blind OFC, the test material should be provided by a physician to ensure proper masking. The food should be prepared without cross-contamination or contact with other foods to which the patient may react13). The procedure must be adjusted according to the stability and allergenicity of the food in question14). Thermal processing, heating, and cooking change protein conformation and may result in a change in allergenicity15). Thus, tolerance to the cooked versions of many foods does not predict tolerance to less cooked forms.

The original OFC vehicle used for blinding was an opaque capsule. However, these capsules have considerable limitations: difficulty in administering adequate quantities of food, possible destruction of allergenicity, probable difficulty in swallowing, bypass of early oral symptoms, and delayed absorption13). Only in cases where there is a suspected reaction to additives is masking in gelatin capsules recommended11). For most OFCs in young children, infant formulas and applesauce are convenient vehicles11, 13).

Dosing schedule for OFC

1. Total dose for OFCs

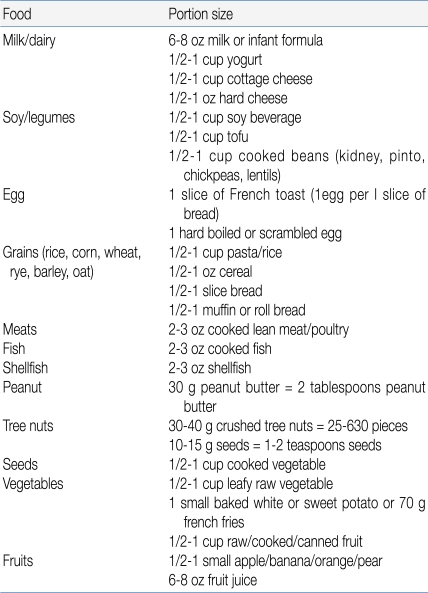

The total dose, that is, the maximal amount of the substance administered, should generally be the normal daily intake in a serving of the food in question, adjusted for the age of the patient. In 1 approach, the total amount administered during a gradually escalating OFC equals 8-10 g of the dry food, 16-26 g of meat or fish, and 100 mL of the wet food16). The challenge food is mixed with the vehicle and administered in gradually increasing increments every 15 minutes. This time interval is preferred because most acute reactions occur within 15 minutes; however, the dosing interval must be adjusted on the basis of a patient's history11, 17). If the patient is expected to tolerate the tested food, an age-appropriated serving of food in its natural form may be served in small potions over a period of 30 to 60 minutes (Table 4)13).

Table 4.

Examples of Portion Sizes *for an Open Food Challenge with Common Food Allergens

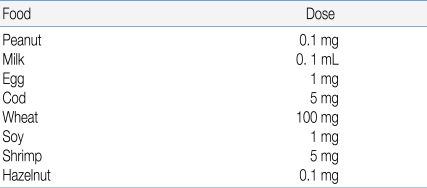

2. Initial challenge dose

The starting dose should be evaluated based on the patient's history and available data from the literature (Table 5)11). According to published data, 5% of patients react to less than 1mg of peanut, whereas 15% of milk allergic patients react to less than 5 mL of cow's milk18, 19). Attempts to predict the outcome of OFCs for egg, through specific IgE assays or SPT end-point titration, have also been made20). If possible, the initial OFC dose should be lower than the expected threshold dose, for example, the amount that the patient developed a reaction to previously. In an open OFC performed according to a simplified protocol, the entire serving of challenge food may be divided into 3 equal portions13).

Table 5.

Proposed Starting Dose for Different Foods

The actual starting dose must always be considered in the actual patient.

Interpretation of OFC

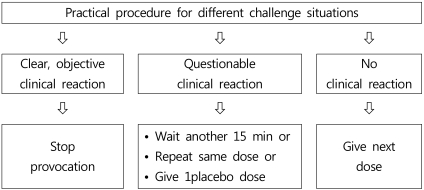

Despite controlled conditions, it is sometimes difficult to determine whether clinical symptoms are sufficiently clear to make a decision. Niggemann et al. proposed a decision tree for various situations during an OFC procedure, which is reproduced in Fig. 27).

Fig. 2.

Decision tree for various situations during oral food challenge procedure.

Different approaches should be taken for patients presenting classical allergic symptoms with objective signs of a reaction on OFC, and for patients presenting subjective symptoms only. In a classical type I allergy with objectively measurable signs, reactions to a placebo are relatively rare and a procedure using one active OFC and one placebo is sufficient21). In contrast, the frequency of reactions to placebo seen in patients presenting subjective symptoms is higher. In these cases, repeated OFC is necessary22). Where an OFC gives a positive result, food elimination may be continued under nutritional supervision. If a negative OFC result is obtained, it is important to ensure that the quantity tolerated by the patient on the day of test corresponds to the amount likely to be eaten during a normal meal.

Risks of OFCs

OFCs should be performed in a setting suitable for the handling of any side effects, including anaphylaxis. This covers the location, the presence of trained personnel, monitoring facilities, and suitable equipment for medical intervention. Intravenous access is a basic safety measure, but complications related to such procedures have been reported, which ranged from local irritation through to thrombophlebitis of the hand or arm23).

It is important to bear in mind the possibility of anaphylactic reaction and to recognize the initial symptoms. Such awareness of symptoms may prevent progression to a more serious clinical situation. H1 antihistamines can mask the early signs of anaphylaxis, and patients with asthma have a higher risk of anaphylaxis10).

Conclusion

The OFC is a valuable tool in the diagnosis and management of children with suspected food allergy. In most cases, OFCs can be performed in a controlled manner without risk. Efforts to standardize OFCs, so that they enable physicians to reach better decisions and avoid unnecessary elimination diets, have been made by The Korean Academy of Pediatric Allergy and Respiratory Disease.

References

- 1.Roehr CC, Edenharter G, Reimann S, Ehlers I, Worm M, Zuberbier T, et al. Food allergy and non-allergic food hypersensitivity in children and adolescents. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1534–1541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sampson HA, McCaskill CC. Food hypersensitivity and atopic dermatitis: evaluation of 113 patients. J Pediatr. 1985;107:669–675. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80390-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verstege A, Mehl A, Rolinck-Werninghaus C, Staden U, nocon M, Beyer K, et al. The predictive value of the skin prick test wheal size for the outcome of oral food challenges. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:1220–1226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.2324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sampson HA. Utility of food-specific IgE concentrations in predicting symptomatic food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:891–896. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.114708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niggemann B, Reibel S, Wahn U. The atopy patch test (APT)-a useful tool for the diagnosis of food allergy in children with atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2000;55:281–285. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruijnzeel-Koomen C, Ortolani C, Aas K, Bindslev-Jensen C, Bjorksten B, Moneret-Vautrin D, et al. Adverse reaction to food. European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology Subcommittee. Allergy. 1995;50:623–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1995.tb02579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niggemann B, Beyer K. Diagnosis of food allergy in children: toward a standardization of food challenge. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:399–404. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318054b0c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niggemann B, Rolinck-Werninghaus C, Mehl A, Binder C, Ziegert M, Beyer K. Controlled oral food challenges in children-when indicated when superfluous? Allergy. 2005;60:865–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gellerstedt M, Magnusson J, Grajö U. Interpretation of subjective symptoms in double-blind placebo-controlled food challenges-interobserver reliability. Allergy. 2004;59:354–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2003.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rance F, Deschildre A, Villard-Truc F, Gomez SA, Paty E, Santos C, et al. Oral food challenge in children: an expert review position paper of the section of Pediatrics of the French Society of Allergology and Clinical Immunology and of the Pediatric Society of Pulmunology and Allergology. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;41:35–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bindslev-Jensen C, Ballmer-Weber BK, Bengtsson U, Blanco C, Ebner C, Hourihane J, et al. Standardization of food challenges in patients with immediate reactions to foods-position paper from the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. Allergy. 2004;59:690–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bahna SL. Food challenge procedure: optimal choices for clinical practice. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007;28:640–646. doi: 10.2500/aap.2007.28.3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Assa'ad AH, Bahna SL, Bock SA, Sicherer SH, Teuber SS. Work group report: oral food challenge testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(6 Suppl):S365–S383. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noè D, Bartemucci L, Mariani N, Cantari D. Practical aspects of preparation of foods for double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge. Allergy. 1998;53(46 Suppl):75–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1998.tb04967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas K, Herouet-Guicheney C, Ladics G. Evaluating the effect of food processing on the potential human allergenicity of novel proteins: international workshop report. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:1116–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mofidi S, Bock SA. A health professional's guide to food challenges. Fairfax: Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor SL, Hefle SL, Bindslev-Jensen C. A consensus protocol for the determination of the threshold dose for allergenic foods: how much is too much? Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:689–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.1886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moneret-Vautrin DA. Cow's milk allergy. Allerg Immunol (Paris) 1999;31:201–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rance F, Abbal M, Lauwers-Cances V. Improved screening for peanut allergy by the combined use of skin prick tests and specific IgE assays. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:1027–1033. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.124775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tripodi S, Di Rienzo Businco A, Alessandri C, Panetta V, Restani P, Matricardi PM. Predicting the outcome of oral food challenges with hen's egg through skin test end-point titration. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:1225–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballmer-Weber BK, Wuthrich B, Wangorsch A, Fotisch K, Altmann F, Vieths S. Carrot allergy: double-blinded, placebo-controlled food challenge and identification of allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:301–307. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.116430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bindslev-Jensen C. Standardization of double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges. Allergy. 2001;56(Suppl 67):75–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2001.00922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reibel S, Rhor C, Ziegert M. What safety measures need to be undertaken in oral food challenge in children? Allergy. 2000;55:940–944. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]