Abstract

In the context of nurse migration, experts view trade agreements as either vehicles for facilitating migration or as contributing to brain-drain phenomena. Using a case study design, this study explored the effects of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) on the development of Mexican nursing. Drawing results from a general thematic analysis of 48 interviews with Mexican nurses and 410 primary and secondary sources, findings show that NAFTA changed the relationship between the State and Mexican nursing. The changed relationship improved the infrastructure capable of producing and monitoring nursing human resources in Mexico. It did not lead to the mass migration of Mexican nurses to the United States and Canada. At the same time, the economic instability provoked by the peso crisis of 1995 slowed the implementation of planned advances. Subsequent neoliberal reforms decreased nurses’ security as workers by minimizing access to full-time positions with benefits, and decreased wages. This article discusses the linkages of these events and the effects on Mexican nurses and the development of the profession. The findings have implications for nursing human resources policy-making and trade in services.

Keywords: Nurses, nurse migration, trade agreements, human resources, health professionals, Mexico

KEY MESSAGES.

When nurse migration is not yet a problem for a country, a trade agreement can change the relationship between the State and the profession to one that focuses on professional infrastructure investment that increases nursing human resource production capacity.

For nurses, even when a vehicle for legal migration via a trade agreement exists, language barriers and role differences can provide significant obstacles to migration.

Minimum educational requirements for nurses that change after the inception of a trade agreement may benefit patient outcomes in the long term due to improved quality of care provided by nurses, but additional studies are needed to demonstrate this effect.

Introduction

The phenomenon of global nurse migration is a multi-billion dollar industry loaded with monetary incentives for governments to promote the migration of their nurses, even if the pattern is harmful to the health system of the country (Kingma 2006). Trade agreements can facilitate an individual nurse’s ability to migrate, contribute to a professional brain-drain in sending countries, or provide critical restrictions on the number of nurses who can migrate annually (Buchan 2006; Kingma 2006; Yan 2006). Yet outside of brain-drain effects on health systems, policy-makers in both trade and human resources for health do not have a good understanding of the domestic effects of trade agreements on the development of the nursing profession, and subsequently, the national system for producing nursing human resources.

In a collective effort, Canada, the United States (USA) and Mexico established the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) to reduce or eliminate trade barriers between the three countries (Frenk et al. 1994; Arboleda Flórez et al. 1999; Gómez Dantes et al. 1997; Sebastian and Hurtig 2004). Mexico offers a unique opportunity to study the long-term effects of a major regional trade agreement on the development of the nursing profession in a country where international nurse migration is not yet a problem. No studies have explored the effects NAFTA had, if any, on the Mexican nursing profession. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to examine whether NAFTA influenced the development of the Mexican nursing profession and if so, how.

Background

In the region of the Americas alone, 83% of all nurses (approximately 3.3 million) work in the USA and Canada (PAHO 2008). With roughly 200 000 nurses in Mexico, they represent approximately 45% of the Mexican health care workforce (CNSM 2004; PAHO 2008; SIARHE 2008). Mexican nursing has multiple levels of education for entry into the profession and graduate education in nursing available up to the PhD level. The Comisión Permanente de Enfermería (CPE) estimates that about 8% of all Mexican nurses have a bachelor’s degree (licenciatura) or higher, thus resulting in a significant shortage of professionally prepared nurses (SIARHE 2008).

In the early stages of NAFTA’s design and implementation, nurses from Mexico, Canada and the USA took the opportunity to compare the status of nurses between the three countries and target areas for development and collaboration (TINAN 1996). More recent research suggests that the incentives for full-time employed nurses to remain practising in Mexico may far outweigh the benefits of migrating for higher salaries and improved working conditions (Squires 2007). In other literature, common themes about the NAFTA and health focus on the potential and actual effects of the agreement upon health, the health care system and health services delivery. Few researchers directly mention Mexican nurses and NAFTA (Laurell and Ortega 1992; Hernández Peña et al. 1993; Frenk et al. 1994; Juan López 1994; Brown 1997; Gómez Dantes et al. 1997; McGuinness 2000). Analyses focused on the traditionally male dominated professions, like law, medicine and engineering, and how the agreement could improve educational standards and the quality of professional services (Ramos Sánchez 1998).

Despite gaps in the literature, the migration of Mexican nurses using Trade Negotiation Visas (TNV) to find legal work as nurses in the USA is always a great source of speculation on both sides of the border. The classic migration push factor of ‘low salaries’ could serve as a migration driver in Mexico because the Comisión Nacional de Salarios Mínimos (CNSM) only recognizes Mexican nurses with licenciatura levels of education—equivalent to a bachelor of science in nursing in the USA—as ‘professionals’ in their salary categories (Cárdenas Jiménez and Zárate Grajales 2001; CNSM 2004). Mexican nursing salaries (from auxiliary nurses to professors) can be as low as US$150 per month, to as high as US$4000 per month (Salas Segura et al. 2002). Geographic location of the nurse’s workplace and type of hospital (public vs. private) affect income, as well as union membership (a positive effect on nurses’ income). Private hospitals in Mexico pay 25–50% less than public, government managed hospitals (Salas Segura et al. 2002; Squires 2007), except in the case of State-level, decentralized hospitals, which pay roughly the same as private hospitals. Historically, however, Mexican health care institutions (public or private) have favoured hiring nurses with the lowest levels of education to keep operating costs low; in the case of private hospitals, the practice aims to maximize profits for the physician owners (PEF 1983; Subsecretaría de Planeación 1986; Balseiro Almario 1987; Rosales Rodríguez and López Andrade 1987; SSA 1989a, b; de Gortari Gorostiza 1991; PEF 1991; Salinas de Gortari 1991).

In consideration of all these factors and since nurses remain a critical component of health services delivery at both the primary and acute care levels in Mexico, determining what kind of effect NAFTA had on the development of the profession and the global mobility of Mexican nurses is important because nurses ultimately affect patient outcomes in a health system and its capacity to respond to population health needs. An analysis of a trade agreement’s effects on the nursing profession may also reveal strategies for mediating the effects of international nurse migration and inform trade agreement design.

Methods

A secondary analysis from a descriptive case study about the professionalization of Mexican nursing between 1980 and 2005 structured this research. Descriptive case studies allow researchers to manage and synthesize large volumes of data, both qualitative and quantitative, with the specific purpose of discovering the nature of relationships between variables (Yin 2009). Secondary analyses permit a researcher to ‘use an existing dataset to find answers to a research question that differs from the primary study’ (Hinds et al. 1997, p. 408). From the initial case study, it was apparent that a significant shift in the professionalization of Mexican nursing occurred after NAFTA that merited deeper exploration and further research.

Therefore, a secondary, directed content analysis structured the analytic approach of the qualitative data from the original case study and descriptive statistics were incorporated to illustrate specific effects of NAFTA on the profession’s infrastructure. Data for this study came from 410 primary and secondary sources about nursing human resources in Mexico and 48 semi-structured, Spanish language interviews with Mexican nurses about professionalization. Participants came from a small network of key informants who were recruited through targeted convenience and snowball sampling techniques. The demographics of the participants from the initial case study are shown in Table 1. The sample was 90% women and 10% men, who were highly professionalized, with 70% of the sample possessing a bachelor’s degree at the time of the interview. Not all had attained a bachelor’s degree as their mode of entry into the profession. The nurses interviewed for the study lived in four states that covered the major geographic and economic regions of the country. Even though interviews were in Spanish, data were coded in English and audited by an independent, bilingual professional to verify the conceptual congruence of the translated coding process. International Review Board (IRB) approval for the study came from the University of Pennsylvania.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Women | 43 (90) |

| Men | 5 (10) |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean | 38.7 |

| Range | 24–62 |

| Experience (%) | |

| Average years (range) | 15.6 (1–42) |

| Adult health/medical–surgical | 60 |

| Paediatric | 26 |

| Ob/gyn | 20 |

| OR/ICU/ED | 24 |

| Administration | 38 |

| Education (hospital) | 17 |

| Education (university) | 36 |

| Public health | 12 |

| Other | 7 |

| Education (%) | |

| Technical/associates | 75 |

| Bachelors | 70 |

| Masters or higher | 43 |

| Civil status and children (%) | |

| Single, never married | 34 |

| Single mother | 24 |

| Married | 68 |

| Divorced | 22 |

| With children | 76 |

| With children at home | 53 |

Findings

In the literature about professions, scholars widely recognize that the relationship between the State and the profession is a critical factor in development and regulation. The significant finding from this analysis is that the creation of NAFTA served as a catalyst for changing the relationship between the Mexican State and the nursing profession. The changed relationship made creating the professional infrastructure that nurses required to support their development easier than in previous periods in Mexican nursing history. The 1995 peso crisis, however, complicated the overall infrastructure development process because it slowed the rate at which these endeavours could occur. Economic policies also altered the workplace of Mexican nurses by making it increasingly difficult to obtain a full-time position in the well-paying, State-managed health care system. The inception of the trade agreement also inserted globalization language into the nursing discourse, appearing in the nursing literature only after NAFTA’s enactment and spontaneously in the interviews with nurses. In sum, NAFTA’s inception appears to have had a series of indirect effects on the development of Mexican nursing that continue to influence its development, even today. The following sections describe the series of effects and their consequences to the profession.

A changed relationship: Mexican nursing and the State

The most important finding of the study is the changed relationship between the State and Mexican nursing. For context, it is useful to know that prior to NAFTA’s creation, nurses were politically marginalized in the policy-making process and health system goals for human resources development rarely aligned with Mexican nursing’s professional development goals. As a result, from the late 1970s through the 1980s, Mexican nursing experienced a deprofessionalization process that diminished their technical authority in the workplace and eliminated nursing leadership within the Department of Health (Squires 2007).

With the advent of NAFTA, however, new incentives for the State to critically examine nursing emerged. NAFTA’s implementation generated what appears to be a federal-level incentive to evaluate the state of nursing in Mexico in preparation for the agreement’s design. The inclusion of North American nurses in the process to develop NAFTA, through the Tri-lateral Initiative for North American Nursing, helped produce concrete evidence of the significant differences between nursing roles. In Mexico, the results of the collective effort began changing the relationship between the nursing profession and the State. The comparative analysis illustrated the potential for Mexican nurses to legally migrate to the USA and Canada for work and send home remittances, but also showed the State and the profession where to focus professional infrastructure building to facilitate the production of nurses and improve the quality of services provided by nurses in Mexico.

The nurses’ new level of access to previously eliminated political capital evolved because if Mexican nursing was to develop to a similar level of professional standing to its North American counterparts, thus placing them on equal grounds for trade in services, the State had to develop or redirect investments towards the development of nursing human resources in Mexico. Hiring patterns also changed in the government-run health system, moving away from their previous bias toward hiring auxiliary nursing personnel. Within the profession, these investments shifted nursing human resources production toward associate degree equivalent and bachelor’s degree prepared nurses. The newfound political capital gave the nurses more freedom to enact changes within their own profession, but as one retired nursing professor stated during an interview, “It would have gone a lot faster if we had the money to make the changes we needed.”

Gender was also a factor in the relationship between the State and the profession as female nursing leaders in Mexico often face multiple competing demands on their time due to social expectations about their roles as wives, mothers, daughters and extended family members. Many expressed frustration that these sociocultural demands hinder the rate at which they can enact change or contribute to the political dialogue, especially if they have children at home. Males participating in the study freely admitted that political relationships were easier for them to make because they faced fewer demands at home, and because most politicians and Secretary of Health leadership are also men.

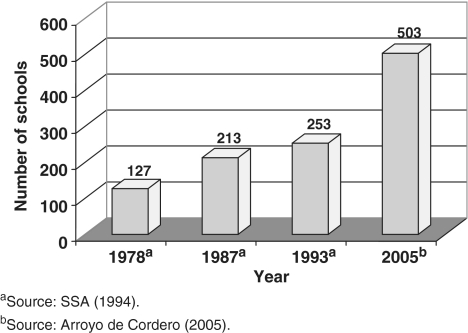

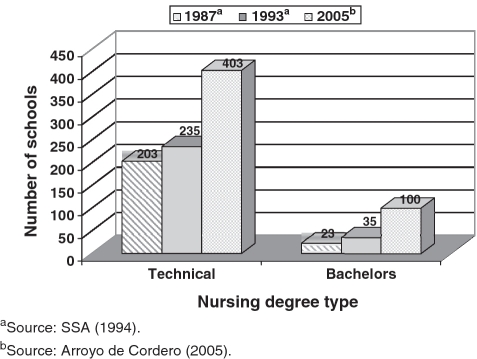

Growth in the production capacity of nursing personnel post-NAFTA

After NAFTA’s 1994 implementation, the growth of private and public nursing programmes, especially at the technical and licenciatura levels, soared. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the growth in nursing schools. Figure 1 shows that in 1993 there were approximately 253 nursing programmes in the country (SSA 1994), nearly doubling to 503 in 2005 (Arroyo de Cordero 2007). As shown in Figure 2, 100 schools offered BSN-level education in 2005 compared with fewer than 40 in 1993. Growth in nursing education programmes did occur, however, without solid accreditation programmes and few educational standards. Shifting the production of nursing human resources to university-based programmes also created a shortage of qualified teachers due to the rapid growth in schools and the lack of bachelor’s and graduate prepared nurses to fill teaching positions. Labour studies by Müggenburg-Rodríguez Vigil and colleagues also indicate that retention rates, even in top nursing programmes, remain low, with the country only graduating around 13 000 nurses per year from all programmes (Müggenburg-Rodríguez Vigil et al. 2000; Müggenburg-Rodríguez Vigil 2004; Müggenburg-Rodríguez Vigil et al. 2006). She and her colleagues attribute high attrition rates to the sociocultural demands placed on the high number of female students from low-income families, who often expect daughters to drop out of school to work when the family faces financial difficulties.

Figure 1.

Growth in total number of Mexican nursing schools: 1978–2005

Figure 2.

Growth in type of nursing programmes: 1987–2005

In consideration of these factors, it becomes apparent that growth in production capacity does not necessarily mean that the national market becomes flooded with nurses and that the excess workers will migrate to work in nursing jobs abroad. Two nursing professors added another dimension to this equation as they described the role of performance capacity of Mexican nurses that evolves from the current educational system, which ultimately affects Mexican nurses’ ability to migrate to work abroad, whether they are male or female. The first professor had a master's degree in health services administration and had worked as a nursing department administrator in the Instituto de Seguridad y Servicio Social para Trabajadores del Estado (ISSSTE) prior to moving to teach in academia in the early 1990s. In her experience, she found that most of the nurses working under her or returning for technical or bachelor’s degree preparation “ … have practiced based on empiric observation of others and just to do the tasks, but not think about what they’re doing … They do not have a sense of what it is to act autonomously and make good decisions.” The second professor provided more detail that illustrates the challenges of working with adult nursing students completing técnico and licenciatura programmes. She said:

“I told you that Mexican nurses…have a facility, an excellent ability to perform procedures. They can compete with any nurse in that area, from any place, but they cannot explain the principles that serve as the foundation for their actions. They know when there is a contraindication (if that happens to be the case)…the reason why there is a danger for a reaction, but they cannot explain the ‘why’ of it, because they lack the theoretical background. Now nurses here have great technical experience, but they lack the theory behind it and the scientific reasoning to justify their actions or describe their reasoning process.”

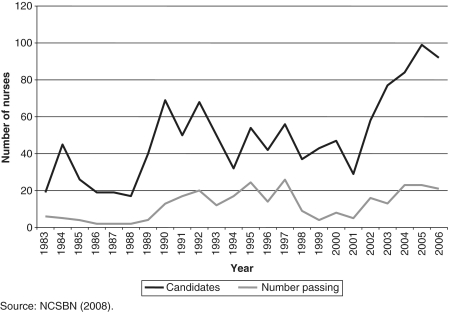

While there are always exceptions to the professors’ assessment, their quotes suggest that having a large capacity to produce nurses does not necessarily mean While there are always exceptions to the professors assessment, their quotes suggest that nurses capable of migrating abroad will emerge from the programmes, especially when English language skills are not part of the curriculum. Yet before even considering the language issues, nurses like the ones the professors described would be unlikely to pass a licensure exam like the US NCLEX-RN nursing licensure examination. In support of the professor's statements, Figure 3 illustrates how 20 plus years of pass rates compare with the numbers of nurses taking the exam (NCSBN 2008). The figure shows that while more nurses have taken the exam in recent years, likely indicating a growing interest in migration for work in the USA, trends in pass rates among Mexican nurses on the NCLEX-RN exam have remained flat over a 25-year period (NCSBN 2008). Until Mexican nursing education is universally standards based with appropriate enforcement through programme accreditation, the quality of graduates will continue to vary widely. Mexico will continue to have good technicians at the bedside, but not necessarily nurses with the critical thinking skills required for improving nursing services within Mexico, let alone migrating abroad for work in US hospitals.

Figure 3.

Trends in Mexican nurses NCLEX examination and pass rates

Fortifying the professional institution

NAFTA appears to have generated a broader professionalization movement within the Mexican government that continues to the present day. Policy changes occurred not only with ‘hard’ infrastructure developments like more nursing schools, but also with soft ones that aligned the broader group characteristics with those classically associated with the professions, like Codes of Ethics and salary changes. This section illustrates the policy progression that fortified professional nursing infrastructure and began after NAFTA’s implementation.

Professionalizing nurses was part of a larger process adopted by the 1994–2000 Zedillo administration in an attempt to professionalize State employees. Professionalization language was found more frequently in national state-of-the-union reports after the implementation of NAFTA. The Zedillo administration used the term ‘professionalizing’ or ‘professionalization’ of government employees in every annual report published during its term. The State viewed professionalization as a means of reducing corruption in the country and improving worker performance (PEF 1997). Regardless of the corruption-tainted reality outside the policy sphere, the desired effect was to make Mexican workers more competitive internationally and create additional opportunities for revenue through remittances sent back to Mexico through worker migration to developed nations. For Mexican nursing during this period, this meant moving entry-level training to the university level and laying the foundation for educational programme accreditation, both important elements in professionalization.

As professional culture development among State employees like nurses progressed into the early 21st century, under the Fox administration the Secretaria de Salud y Asistencia (SSA) collaborated with health care professionals to develop professional Codes of Ethics for all health care workers, a key element of soft professional infrastructure. Yet ahead of these State-driven initiatives, Mexican nurses developed their own Codes of Ethics for dissemination throughout the country 3 years in advance of the publication of Codes of Ethics for other health care professionals (CIE 2001a, b). The State provided the institutional support to organize the committee charged with developing the Codes of Ethics and its eventual publication. Nonetheless, in an illustration of the academic and practice reality disconnection common within professions, this study found that the dissemination of the Codes of Ethics was poor as none of the 28 staff nurses and only seven out of 14 nursing administrators in this study were aware of its existence.

For Mexican nursing, another key ‘hard’ professional infrastructure investment by the State was the development of the national nursing human resources database in the SSA, known as the Sistema de Información Administrativa de Recursos Humanos en Enfermería (SIARHE). The SSA also developed both national and decentralized State-level commissions to address nursing human resources development issues nationally and locally (IMSS 1996; SSA 1997; PEF 1999). A fully operational system, however, took nearly 10 years to develop because the rate of implementation was slowed by the 1995 peso crisis and the ensuing economic instability that lasted until about 1999.

Nonetheless, the development of SIARHE eventually led to the creation of the Comisión Interinstitucional de Enfermería (CIE) in 2002, perhaps the biggest symbol of the improved quality of professional institutions that Mexican nurses gained after NAFTA (CIE 2001b). The CIE was a national, State-supported division of the SSA designed to support the development of nursing services throughout the country. Nurses lead the institution and have a representative from every state so that policies and programmes emerging from the CIE can disseminate to the local nursing communities. It provides a centralized leadership body for Mexican nursing within the Mexican government with the capacity to tailor broad policy goals to local needs through the state representatives.

The sustainability of the institution, however, depends largely on the political will of the State to continue supporting its operations and the ability of nurses to produce qualified leadership to run it. To provide some sustainability for the institution, President Felipe Calderón made the institution a permanent part of the Ministry of Health through a presidential decree in 2007, creating the Comisión Permanente de Enfermería (CPE). Furthermore, in a local level example, in the state of Nuevo Leon in northern Mexico that borders Texas, the state government supported the creation of a centralized nursing institution to help disseminate the CPE’s work and provided them office space to coordinate their activities. The building now houses all professional nursing and other nursing specialty organizations in the state.

Challenges to institutions and capacity building: the 1995 peso crisis

A paediatric nurse in the study described the 1995 peso crisis as “ … the moment when everything stopped”. The 1995 peso crisis negatively effected how Mexican states were able to provide health services as many could not cope with the loss of resources from the federal system. Health care financing within the Instituto Mexicano de Seguro Social (IMSS) was reduced by 89.5% (PEF 1995). Decreased financing forced states to decrease investment in health system infrastructure and freeze wages in order to maintain basic services. Enrolments in nursing schools also dropped by 50% or more (Sánchez de Leon and Castro Ibarra 1996; Vargas Daza and Solis Guzmán 1997). For Mexican nursing, professional infrastructure developments begun as part of NAFTA’s implementation slowed to a trickle and priorities shifted to simply keeping existing infrastructure running. Other studies conducted by Mexican nurse researchers show that family demands rooted in familial financial difficulties formed the top reason for dropping out of any kind of nursing programme (Sánchez de Leon and Castro Ibarra 1996; Uribe Calderón 1997; Vargas Daza and Solis Guzmán 1997). The combination of these factors affected the rate at which NAFTA-generated changes within Mexican nursing could progress.

The private sector

Notably absent from the intersection between NAFTA and Mexican nursing is the role of the private sector. The results from this study showed that despite a host of incentives—especially those related to the recruitment and placement of nurses—the private sector plays no significant role within or apart from Mexican nursing, other than the existence of private hospitals as a low-paid employment option. Only one private hospital consortium does provide financial support for the only non-State-funded Mexican nursing journal, Desarollo Científico en Enfermería, but that is about the extent of its involvement in the development of the profession. A variety of media also reported on other private sector examples in the early 2000s as several businesses developed agencies to facilitate Mexican nurse migration to the USA through TNVs. Yet, the majority of these ventures failed because the owners grossly underestimated the extent to which they would have to invest in English language training, nursing licensure exam preparation and role transition issues.

Discussion

This study had several limitations related to the data, sample demographics, geographical distribution of the participants, sampling strategy, translation and researcher identity. The generalizability of these findings to other countries in Latin America or other parts of the world may be limited. A general limitation of case studies and secondary analyses is that the quality of the data affects the results (Hinds et al. 1997; Yin 2009). While Mexico has reliable data and excellent archives, the nursing data were sparse and not gender differentiated. National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) data do not differentiate scores by gender, so exploring the gender effect on NCLEX-RN testing by Mexican nurses was not possible. The fact that translated qualitative data were part of this study automatically makes it a limitation because of the risk of conceptual drift during the translation processes (Squires 2008). Finally, the researcher’s identity as a foreigner may have affected participant responses during the interviews.

Despite the limitations, the findings from this study suggest that trade agreements like NAFTA, with provisions for trade in nursing services, appear to provide an incentive for national governments to improve the quality of the professional institutions and the infrastructure that supports nursing at the country level. When these incentives become sufficient for the State to make that kind of investment, it changes the nature of the political relationship between the State and nursing professionals. In this case, the relationship appeared to improve because roles for nurses in health system policy-making increased and they gained greater autonomy in professional governance. The success and strength of the new relationship, however, appears tied to economic stability.

Somewhat ironically, a stronger relationship between the profession and the State goes against one of the tenets of Neoliberalism, the economic theory that has driven most economic policies around the world in the last 30 years. The theory advocates minimizing the role of the State in all aspects of public life and letting market forces address as much as possible. From this study, it was apparent that a lack of a relationship between the State and the nursing profession had hampered the development of the profession and affected the quality of nursing services. Market forces created the least prepared nurses to work in Mexican health care facilities. The private sector had no incentive to get involved in developing nursing human resources because, as noted previously, the capital and time investment proved too high and too risky for most private sector investors. Furthermore, Mexican nursing, as a female-dominated profession drawing candidates largely from the middle and lower classes, faced multiple barriers (social roles, class barriers, gender related, etc.) to steering its own development due to the inability to secure financial or political capital that would enhance its development as a group. That leaves the State and the profession as the institutions that can invest in developing nursing services, from entry-level personnel through to researchers who can study nursing interventions that can improve the quality of care.

Even with a more productive relationship investing in institution building that promotes the development of nursing human resources, the dynamics of a national economy, affected by a trade agreement or not, permeate every aspect of the process of building professional infrastructure. From the results, it was very clear that the economic instability occurring after NAFTA had a profound effect on the development of Mexican nursing as a profession and their place of work. As a capital-dependent process, professionalization requires financial resources to facilitate education, political relationships with the State and knowledge production. For Mexican nurses, these financial resources are tied into the State’s economic policies and, of course, influenced by the trade agreements that shape them. Economic instability produced by these policies then inhibits the rate at which professionalization occurs because nurses have more difficulty securing the capital they need to promote the advancement of the group as a whole and to improve the quality of services they provide to the public. Thus, in the face of economic instability, migration for work as a nurse removes itself as an option without a strong professional development system derived from strong infrastructure.

Yet as Figure 3 shows, more Mexican nurses take the licensure exam every year. The data indicate a growing interest among Mexican nurses in migrating abroad for work, but the proportion that passes the exam remains low. That suggests that despite the incentives provided by NAFTA for legal migration to the USA, the current institutional infrastructure is not capable of producing large numbers of bilingual nursing professionals capable of passing the NCLEX-RN exam. This finding indicates that there are opportunities for the private sector and others to invest in developing nurses or their educational programmes so that Mexican nurses who choose to work abroad are capable of passing the exam. This type of venture may also require more capital (both financial and in human expertise) than many enterprising business people can find or would be willing to invest. This investment would also require significant cooperation with not only the organized arms of Mexican nursing, but also the State.

In light of these factors, the State will have to continue to invest in the Mexican nursing profession in ways that promote sustainable growth in personnel and infrastructure. Expecting capacity development to come entirely from the profession itself is unrealistic at this time in Mexico or in most developing countries. Mexican nursing’s 20th century history as a female-dominated profession with a history of political marginalization, the primary sources of entrants into the profession coming from economically marginalized lower and middle classes in Mexico, and their competing roles as Mexican wives and mothers, confound the collective ability for Mexican nurses to take a larger role in infrastructure development. It becomes considerably more difficult for them to independently secure capital for their individual and group development when these factors are present. These changes will occur, but at the pace the profession is able to generate. This may prove slower than many interested parties desire. History, however, does show a high return on investment in developing the capacity of nursing professionals, as with increased autonomy, resources and governance over their profession, the quality of nursing services improves in concert with population health.

In the long term, NAFTA’s indirect effects on professional infrastructure development coupled with changes within Mexican nursing might affect patient outcomes in hospitals, public or private. For example, now that the licenciatura is the preferred level of education required of nurses for obtaining a TNV, it has set a standard for Mexican nursing education and also shifted public-sector hiring practices. Domestically, this policy change also has the potential to positively change patient outcomes, at least in the hospital setting. The previous bias in hiring practices toward hiring only auxiliary nurses may have cost the health system more money in the long term because, as nursing workforce research now demonstrates, nurses with low levels of education result in poor quality of care and poor patient outcomes (Aiken et al. 2001a, b; Stanton 2003; McElmurray et al. 2006; Lake 2007). Studies capturing patient outcome trends related to nurse staffing and the demographics of nursing in Mexican hospitals would be able to evaluate trends in patient outcomes before and after NAFTA’s implementation and further quantify the existence of that kind of effect, if such data exist.

In conclusion, the findings from this study are complex in the series of relationships and consequences resulting from a trade agreement like NAFTA. The findings suggest that designers of trade agreements should consider thinking beyond remittances and look more at how an agreement promotes infrastructure development that supports the production and retention of nursing personnel. Overall, this study demonstrates the need for more research about the domestic effects of trade agreements on the complex developmental process of nursing and health care human resources production and professional infrastructure development. Data from these studies will help shed further light on the positive and negative effects trade agreements have on health care professionals.

Funding

This work was funded by a post-doctoral fellowship from the National Institute for Nursing Research, NIH award ‘Advanced Training in Nursing Outcomes Research’ (T32-NR-007104, Linda Aiken, PI), the Yale MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies Pre-Dissertation and Dissertation Support Small Grants, Sigma Theta Tau International – Delta Mu Chapter Small Research Grant, and Sigma Theta Tau International Small Grants.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the 48 participants and countless other Mexican nurses who inspired this research.

References

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski JA. An international perspective on hospital nurses’ work environments: the case for reform. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice. 2001a;2:255–63. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, et al. Nurses’ reports on hospital care in five countries. Health Affairs. 2001b;20:43–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arboleda Flórez J, Stuart HL, Freeman P, González Block MA. Access to Health Services Under NAFTA. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo de Cordero G. Sistema Educativo de Enfermería. 2005 Powerpoint presentation online at: http:/www.salud.gob.mx/unidades/dgces/foro_enf/descargas/06.ppt, accessed 5 May 2007. Comision Interinstitucional de Enfermería, Mexico D.F. [Google Scholar]

- Balseiro Almario L. La organización de enfermería y su repercusión en la toma de decisiones (primera parte) [The organization of nursing and the repercussions on decision making] Enfermera al Día. 1987;12:11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JC. What historians reveal about labor and free trade in Latin America. Work and Occupations. 1997;24:381–98. [Google Scholar]

- Buchan J. The impact of global nursing migration on health services delivery. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice. 2006;7:16S–25S. doi: 10.1177/1527154406291520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas Jiménez M, Zárate Grajales RA. La formación y la práctica social de la profesión de enfermería en México. [The formation and social practice of the nursing profession in Mexico] Investigación y Educación en Enfermería. 2001;19:92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Interinstitucional de Enfermería [CIE] Código de Etica para las Enfermeras y Enfermeros en México. [Code of Ethics for Mexican Nurses] Mexico D.F.: Secretaria de Salud y Asistencia; 2001a. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Interinstitucional de Enfermería [CIE] Plan Rector de Enfermería. 2001b [Governing Plan for the Development of Nursing.]. Mexico D.F.: Secretaria de Salud y Asistencia. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional de Salarios Mínimos [CNSM] Boletín de prensa. 2004. 16 December. Mexico, D.F.: Comisión Nacional de Salarios Minimos. [Google Scholar]

- de Gortari Gorostiza E. Recursos humanos y materiales para la atención de la salud [Human resources and supplies for healthcare] 1991 Primera reunión nacional: salud y enfermedad en el medio rural de México [First national conference on health and illness in the rural setting]. Mexico, D.F.: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, pp. 161–71. [Google Scholar]

- Frenk J, Gómez Dantes O, Cruz C, et al. Consequences of the North American Free Trade Agreement for Health Services: a perspective from Mexico. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:1591–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.10.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Dantes O, Frenk J, Cruz C. Commerce in health services in North America within the context of the North American Free Trade Agreement. Pan American Journal of Public Health. 1997;1:460–5. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49891997000600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Peña P, Gutierrez Zuniga C, Zurutuza Fernández R, Jiménez González O. The free-trade-agreement and environmental health in Mexico. Salud Pública de México. 1993;35:119–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds PS, Vogel RJ, Clarke-Steffen R. The possibilities and pitfalls of doing a secondary analysis of a qualitative dataset. Qualitative Health Research. 1997;7:408–24. [Google Scholar]

- IMSS. Lineamientos Estrategicos: 1996–2000. 1996. [Strategic Development Initiatives]. Mexico, D.F.: Instituto Mexicano de Seguro Social. [Google Scholar]

- Juan López M. Sanitary regulation in Mexico and the North American Free Trade Agreement. Salud Pública de México. 1994;36:617–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingma M. Nurses on the Move: Migration and the Global Health Care Economy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lake ET. The nursing practice environment: measurement and evidence. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(Suppl)(.):104S–22S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707299253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurell AC, Ortega ME. The free-trade agreement and the Mexican health sector. International Journal of Health Services. 1992;22:331–7. doi: 10.2190/V2XG-18V2-5UX1-QGKE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElmurray BJ, Solheim K, Kishi R, et al. Ethical concerns in nurse migration. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2006;22:226–35. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness MJ. The politics of labor regulation in North America: a reconsideration of labor law enforcement in Mexico. University of Pennsylvania International Journal of Economic Law. 2000;21:1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Müggenburg-Rodríguez Vigil MC. Mercado de trabajo – profesión de enfermería – egresados de la ENEO. [The labor market, nursing profession, and ENEO graduates.] Enfermería Universitaria. 2004;1:31–4. [Google Scholar]

- Müggenburg-Rodríguez Vigil MC, Castañeda Sánchez E, Franco Paredes W. Seguimiento de los egresados de la ENEO en 1995, a los tres años de su egreso (1998). [Follow-up of 1995 graduates from the ENEO, three years later (1998).] Enfermeras. 2000;36:4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Müggenburg-Rodríguez Vigil MC, Barreto Plácido F, Garcia Ortíz M. Seguimiento de egresados de la licenciatura en enfermería de la ENEO en 2000 a los tres años (2003). [Follow-up of nursing bachelor's degree graduates from the ENEO in 2000 three years later (2003).] Enfermería Universitaria. 2006;3:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing [NCSBN] Nurse licensure and NCLEX examination statistics: 1983–2008. 2008 Online at: https://www.ncsbn.org/1236.htm, accessed 19 January 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) PAHO Mexico Regional Office, National Health Statistics. 2008 Online at: http://www.mex.ops-oms.org/, accessed 1 November 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Poder Ejecutivo Federal (PEF) Plan Nacional de Desarollo 1983–1988 [National Development Plan 1983–1988] Mexico, D.F.: Poder Ejecutivo Federal; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Poder Ejecutivo Federal (PEF) Plan Nacional de Desarollo: Informe de Ejecución 1990 – Anexo [National Development Plan: 1990 Progress Report, Appendix] Mexico, D.F.: Poder Ejecutivo Federal; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Poder Ejecutivo Federal (PEF) Programa de Reforma del Sector Salud: 1995–2000 [Program for Health Sector Reform: 1995–2000] Mexico D.F.: Poder Ejecutivo Federal; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Poder Ejecutivo Federal (PEF) Plan Nacional de Desarollo: Informe de Ejecución 1996 [National Development Plan: 1996 Progress Report] Mexico D.F.: Poder Ejecutivo Federal; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Poder Ejecutivo Federal (PEF) Quinto Informe de Gobierno [Fifth Government Progress Report] Mexico D.F.: Poder Ejecutivo Federal; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos Sánchez D. La Inserción de México en la Globalización y Regionalización de las Profesiones [The Insertion of Mexico into the Process of Globalization and Regionalization of the Professions] Mexico, D.F.: Instituto Politécnico Nacional; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rosales Rodríguez L, López Andrade G. 1987. El perfil de enfermería en salud pública para el modelo de atención primaria de la salud. Enfermería [The role of public health nursing in primary care. In: Nursing.]. Mexico, D.F.: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, pp. 81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Salas Segura S, Zárate Grajales R, Rubio Dominguez S. Aportaciones de la Enfermería en el Sistema de Salud: Estudio de Caso [Contributions of Nursing to the Health Care System: A Case Study.] Mexico, D.F.: Escuela Nacional de Enfermería y Obstetricia; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas de Gortari C. Tercer Informe del Gobierno [Third Government Progress Report] Mexico, D.F.: Poder Ejecutivo Federal; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez de Leon ME, Castro Ibarra EM. Factores asociados a la deserción de la enfermera de los cursos post-técnicos de instituto mexicano de seguro social. [Factors associated with nurse desertion from post-technical training courses in the Mexican social security institute.] Desarollo Científico de Enfermería. 1996;4:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian MS, Hurtig AK. Moving on from NAFTA to the FTAA? The impact of trade agreements on social and health conditions in the Americas. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública/Pan American Journal of Public Health. 2004;16:272–8. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892004001000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIARHE. Estadisticas de Personal de Enfermería. 2008 Online at: http://www.salud.gob.mx/unidades/cie/siarhe/, accessed 1 November 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Squires AP. A case study of the professionalization of Mexican nursing: 1980 to 2005. 2007 Doctoral dissertation, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Squires A. Language barriers and qualitative research: methodological considerations. International Nursing Review. 2008;55:265–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SSA. Avances en el Cumplimiento de Compromisos Presidenciales en Materia de Salud [Advancements in the Completion of Presidencial Promises in Health Matters] Mexico, D.F.: Secretaria de Salud y Asistencia; 1989a. [Google Scholar]

- SSA. Servicios Coordinados de Salud Pública en el Estado de Oaxaca: Programa de Apoyo a los Servicios de Salud Para Población Abierta [Coordinated Public Health Services in Oaxaca State: Program of Support for the Uncovered Population] Mexico, D.F.: Secretaría de Salud y Asistencia; 1989b. [Google Scholar]

- SSA. Directorio de Facultades y Escuelas de Enfermería por Entidad Federativa [State Directory of Nursing Colleges and Universities] Mexico, D.F.: Secretaría de Salud y Asistencia; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- SSA. Programa de Estímulos a la Productividad y Calidad en Favor del Personal de Enfermería [Stimulus Program for Improving the Productivity and Quality of Nursing Personnel] Mexico, D.F.: Secretaría de Salud y Asistencia; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton MW. Hospital nurse staffing and quality of care: research in action. Hospital Nurse Staffing and Quality of Care. 2003;14:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Subsecretaría de Planeación. Programa de Mejoramiento de Servicios de Salud: Mexico – Banco Interamericano de Desarollo [Health Services Improvement Program from the Interamerican Development Bank] Mexico, D.F.: Secretaría de Salud y Asistencia; 1986. pp. 29–32, 58–61, 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Trilateral Initiative on North American Nursing [TINAN] An Assessment of North American Nursing. Philadelphia: Commission on Graduates of Foreign Nursing Schools; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Uribe Calderón F. Informe Anual: 1996 marzo 1997. Mexico D.F.: Cruz Roja Mexicana; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Daza ER, Solis Guzmán C. Causas que generan la falta de titulación de los egresados de los cursos de enfermería a nivel técnico ENEO-UNAM. [Causes of failure to graduate among technical level students in the ENEO-UNAM.] Desarollo Científico de Enfermería. 1997;5:117–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yan J. Health services delivery: reframing policies for global nursing migration in North America – a Caribbean perspective. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice. 2006;7:71S–75S. doi: 10.1177/1527154406294629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. (4th edn). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]