Abstract

Rationale: Acetaminophen has been hypothesized to increase the risk of asthma and allergic disease, and geohelminth infection to reduce the risk, but evidence from longitudinal cohort studies is lacking.

Objectives: To investigate the independent effects of these exposures on the incidence of wheeze and eczema in a birth cohort.

Methods: In 2005–2006 a population-based cohort of 1,065 pregnant women from Butajira, Ethiopia, was established, to whom 1,006 live singleton babies were born. At ages 1 and 3, questionnaire data were collected on wheeze, eczema, child's use of acetaminophen, and various potential confounders, along with a stool sample for geohelminth analysis. Those without wheeze (n = 756) or eczema (n = 780) at age 1 were analyzed to determine the independent effects of geohelminth infection and acetaminophen use in the first year of life on the incidence of wheeze and eczema by age 3.

Measurements and Main Results: Wheeze and eczema incidence between the ages of 1 and 3 were reported in 7.7% (58 of 756) and 7.3% (57 of 780) of children, respectively. Acetaminophen use was significantly associated with a dose-dependent increased risk of incident wheeze (adjusted odds ratio = 1.88 and 95% confidence interval 1.03–3.44 for one to three tablets and 7.25 and 2.02–25.95 for ≥4 tablets in the past month at age 1 vs. never), but not eczema. Geohelminth infection was insufficiently prevalent (<4%) to compute estimates of effect.

Conclusions: These findings suggest frequent acetaminophen use early in life increases the risk of new-onset wheeze, whereas the role of geohelminth infection on allergic disease incidence remains to be seen as the cohort matures.

Keywords: acetaminophen, parasite, asthma, wheeze, eczema

AT A GLANCE COMMENTARY.

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Acetaminophen has been consistently linked with an increased risk of asthma and allergy but evidence of causality is limited by a lack of longitudinal studies.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This study explores the longitudinal effect of acetaminophen use in early life on the incidence of allergic disease in children and shows a positive dose–response association with the risk of new-onset wheeze, providing further support for a causal role of acetaminophen in the etiology of asthma.

Asthma has become one of the most common disorders among children and adults (1). Epidemiologic studies have demonstrated a higher prevalence of asthma and related allergic conditions in more developed countries, and increases in prevalence over recent decades in both developed and developing countries, observations that are likely largely caused by environmental factors (1–3). One such environmental factor that has attracted interest, and that fits with the “hygiene hypothesis” (4), is geohelminth infection. An increasing body of evidence points to geohelminth infection, particularly hookworm infection, protecting against asthma and allergic conditions (5, 6).

Also attracting recent interest but lacking longitudinal support is the hypothesis that acetaminophen use might increase the risk of asthma and allergic disease, and that the shift from aspirin to acetaminophen use may have contributed to the rise in these conditions over recent decades (7). The evidence to date implicating acetaminophen in the etiology of asthma and other allergic diseases has been remarkably consistent (7–20), with adverse effects reported in relation to acetaminophen exposure in utero (8–11), during infancy (11, 12), in childhood (13, 14), and during adult life (15–18). The relation also extends to objective markers of allergy (14–16). However, support from prospective data is limited to one study in women that reported an increased risk of adult-onset asthma in relation to frequent use of acetaminophen (18). Studies have also tended to rely on recall of acetaminophen use in the past, or have not adequately eliminated the possibility of confounding by early respiratory infections, a problem highlighted by Beasley and coworkers (13). Moreover, in studies based in developed countries, the possibility that acetaminophen and asthma are associated through aspirin avoidance is difficult to exclude.

The aim of this study was therefore to establish the temporal relation between early infection with geohelminths and use of acetaminophen in the first year of life, and the incidence of childhood wheeze and eczema in an Ethiopian birth cohort. Some of the results of this study have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (21).

METHODS

Study Setting and Design

The study was sited in and around Butajira, which is located 130 km south of the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa. The Butajira Rural Health Program (BRHP), a demographic surveillance site covering nine rural and one urban (Butajira town) administrative areas, was set up in 1987 (22). In 2005 a birth cohort nested in the BRHP was established, a detailed description of which has been published previously (23, 24). In brief, all women in the BRHP aged 15–49 and in their third trimester of pregnancy were identified by the BRHP fieldworkers between July 2005 and February 2006 and invited to participate in the study. Of the 1,234 eligible women, 1,065 were recruited (86% of eligible) and all live singleton babies born to these women (n = 1006) were followed-up as a birth cohort.

Data Collection and Measurements

Data were collected on the cohort at intervals from pregnancy to age 3, primarily using interview-led questionnaires administered to mothers. Information on demographic factors was collected during pregnancy and numerous additional potential confounders at birth, 2 months, first birthday, and third birthday (see online supplement). Symptoms of respiratory tract infection (cough, fast breathing, and fever) were collected at 2 months and 1 year.

At age 1 and 3, wheeze-ever and eczema-ever were ascertained using questions from the International Study for Asthma and Allergies in Children, and mothers were also asked if the child had taken any acetaminophen in the last year and if so, how much in the last month (see online supplement). In addition to the questionnaire, stool samples were collected at age 1 and 3 and qualitatively examined for geohelminth infections using the formol-ether concentration method (25).

Statistical Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 11 (Statacorp, College Station, TX). Exposure to any geohelminth infection was defined as infection with any of hookworm, Ascaris lumbricoides, or Trichuris trichiura. To assess associations with incidence of new-onset wheeze between age 1 and 3, those children without reported wheeze-ever at age 1 were selected for analysis, and the outcome defined as reported wheeze-ever at age 3. Similarly, children without eczema-ever at age 1 were selected for analysis of incident eczema, defined as a positive response at age 3. Multiple logistic regression was performed to compute adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for incident wheeze and eczema in relation to the acetaminophen group and geohelminth infection, controlling for a priori confounders place of residence, child's sex, and maternal education (as a marker of socioeconomic status). The impact of further controlling for any other potential confounders collected including early life respiratory tract infections (cough, fever, and fast breathing) was also explored.

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted by the National Ethics Review Committee of the Ethiopian Science and Technology Ministry and the University of Nottingham ethics committee, United Kingdom. Written consent was obtained from the mothers, and in keeping with the requirements of the Ethiopian ethics committee all women and their children were reimbursed for health care costs.

Role of the Funding Source

The study sponsors had no role in study design, data collection, analysis of the data, interpretation and writing of the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

RESULTS

Description of Cohort Participants

Of the 1,006 babies in the cohort, 64 (6.4%) had died and 10 (0.9%) migrated from the study area before their first birthday, and a further 33 had missing data on core variables at age 1, leaving 899 (89%) available for analyses at 1 year. A detailed description of the cohort at year 1 is reported elsewhere (24). Of these, 95% (853) were followed-up and outcome data collected at age 3; 17 died, 27 migrated, and 2 were lost with unidentified reason between ages 1 and 3.

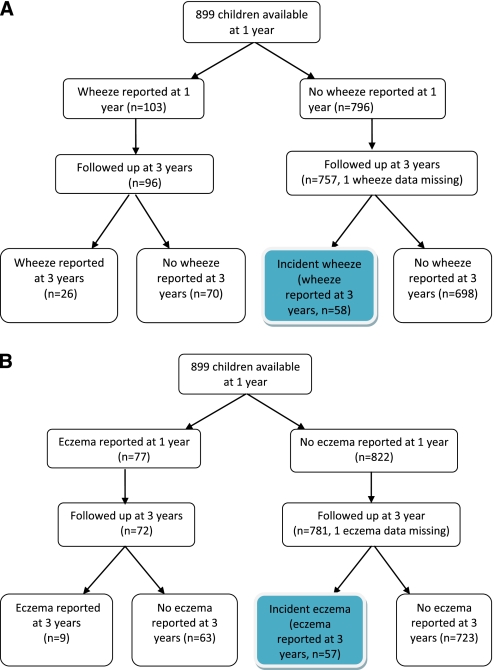

Natural History of Wheeze and Eczema between Ages One and Three

Of the 96 children with reported wheeze-ever at age 1 who were successfully followed-up, 26 (27.1%) still reported wheeze-ever at age 3 and 70 (72.9%) did not report wheeze-ever at age 3 (Figure 1A). Of the 756 nonwheezers at age 1, 58 (7.7%) reported wheeze-ever at age 3 and were defined as incident wheezers (Figure 1A). Similarly, of the 72 children with reported eczema-ever at age 1, 9 (12.5%) still reported eczema at age 3, with the other 63 (87.5%) not reporting eczema at age 3 (Figure 1B). Incident eczema was reported in 7.3% (57 of 780) of children without reported eczema at age 1 followed to age 3 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Flow chart showing reporting of wheeze between 1 and 3 years. (B) Flow chart showing reporting of eczema between 1 and 3 years.

Determinants of Incident Wheeze and Eczema

Table 1 shows the distribution of demographic and potential confounding variables among the wheeze- and eczema-free children at age 1 on whom subsequent analyses were performed. Most of the children lived in rural areas (87%) and had mothers without formal education (80%). The risk of incident wheeze was nonsignificantly greater in urban children and in boys, and significantly greater in those of low birth weight (Table 1). There was a borderline significant increased risk of new-onset eczema in girls and those in large households, and a significant increased risk with increasing number of older siblings (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

DISTRIBUTION OF POTENTIAL CONFOUNDERS AND ASSOCIATION WITH INCIDENCE OF WHEEZE AND ECZEMA

| Wheeze Never at Age 1 (n = 756) | Eczema Never at Age 1 (n = 780) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Overall n (%) | New Wheeze* n (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | P Value | Overall n (%) | New Eczema* n (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | P Value |

| Area of residence | ||||||||

| Urban | 95 (12.6) | 10 (10.5) | 1.50 (0.73–3.08) | 0.27 | 98 (12.6) | 8 (8.2) | 1.15 (0.53–2.50) | 0.73 |

| Rural | 661 (87.4) | 48 (7.3) | 1 | 682 (87.4) | 49 (7.2) | 1 | ||

| Maternal age | 0.92† | 0.32† | ||||||

| 15–24 | 293 (38.8) | 21 (7.2) | 0.88 (0.39–1.99) | 0.71‡ | 297 (38.1) | 19 (6.4) | 1.25 (0.49–3.22) | 0.96‡ |

| 25–34 | 351 (46.4) | 28 (8) | 0.99 (0.45–2.17) | 367 (47.1) | 32 (8.7) | 1.75 (0.71–4.30) | ||

| 35–44 | 112 (14.8) | 9 (8) | 1 | 116 (14.9) | 6 (5.2) | |||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 378 (50) | 33 (8.7) | 1.35 (0.79–2.32) | 0.28 | 394 (50.5) | 22 (5.6) | 0.59 (0.34–1.03) | 0.06 |

| Female | 378 (50) | 25 (6.6) | 1 | 386 (49.5) | 35 (9.1) | 1 | ||

| Maternal education | ||||||||

| Formal | 148 (19.6) | 16 (10.8) | 1.63 (0.89–2.99) | 0.11 | 155 (19.9) | 12 (7.7) | 1.08 (0.56–2.10) | 0.82 |

| No formal | 608 (80.4) | 42 (6.9) | 1 | 625 (80.1) | 45 (7.2) | 1 | ||

| Exclusively breastfed§ | ||||||||

| Yes | 633 (84.1) | 51 (8.1) | 1.41 (0.63–3.20) | 0.40 | 659 (84.7) | 49 (7.4) | 1.11 (0.51–2.42) | 0.78 |

| No | 120 (15.9) | 7 (5.8) | 1 | 119 (15.3) | 8 (6.7) | 1 | ||

| Vaccination at 2 mo‖ | ||||||||

| Yes | 443 (58.8) | 35 (7.9) | 1.07 (0.62–1.85) | 0.81 | 463 (59.5) | 34 (7.3) | 1.01 (0.58–1.74) | 0.98 |

| No | 310 (41.2) | 23 (7.4) | 1 | 315 (40.5) | 23 (7.3) | 1 | ||

| Birth weight | ||||||||

| Low (<2.5 kg) | 35 (7) | 6 (17.1) | 2.73 (1.06–7.04) | 0.04 | 39 (7.4) | 1 (2.6) | 0.32 (0.04–2.40) | 0.27 |

| Normal | 468 (93) | 33 (7.1) | 1 | 487 (92.6) | 37 (7.6) | 1 | ||

| Parental allergic history | ||||||||

| Yes | 39 (5.2) | 4 (10.3) | 1.40 (0.48–4.08) | 0.54 | 42 (5.4) | 3 (7.1) | 0.97 (0.29–3.25) | 0.96 |

| No | 714 (94.8) | 54 (7.6) | 1 | 736 (94.6) | 54 (7.3) | 1 | ||

| Insecticide use in home | ||||||||

| Yes | 623 (82.4) | 46 (7.4) | 0.81 (0.42–1.57) | 0.53 | 648 (83.3) | 50 (7.7) | 1.47 (0.65–3.32) | 0.36 |

| No | 133 (17.6) | 12 (9) | 1 | 130 (16.7) | 7 (5.4) | 1 | ||

| Household size | 0.58† | 0.11† | ||||||

| 1–3 | 98 (13) | 7 (7.1) | 1 | 0.58‡ | 89 (11.4) | 5 (5.6) | 1 | 0.06‡ |

| 4–6 | 422 (55.8) | 36 (8.5) | 1.21 (0.52–2.81) | 446 (57.3) | 27 (6.1) | 1.08 (0.41–2.89) | ||

| 7+ | 236 (31.2) | 15 (6.4) | 0.88 (0.35–2.24) | 243 (31.2) | 25 (10.3) | 1.93 (0.71–5.20) | ||

| No. of older siblings | 0.52† | 0.01† | ||||||

| 0 | 111 (14.7) | 7 (6.3) | 1 | 0.81‡ | 104 (13.4) | 3 (2.9) | 1 | 0.002‡ |

| 1–3 | 415 (54.9) | 36 (8.7) | 1.41 (0.61–3.26) | 437 (56.2) | 27 (6.2) | 2.22 (0.66–7.45) | ||

| 4–10 | 230 (30.4) | 15 (6.5) | 1.04 (0.41–2.62) | 237 (30.5) | 27 (11.4) | 4.33 (1.28–14.61) | ||

| Child's sleeping place | 0.87† | 0.89† | ||||||

| Bed/platform | 59 (7.8) | 5 (8.5) | 1 | 59 (7.6) | 5 (8.5) | 1 | ||

| Floor | 324 (42.9) | 23 (7.1) | 0.83 (0.30–2.26) | 344 (44.3) | 26 (7.6) | 0.88 (0.32–2.40) | ||

| Grass matting | 372 (49.3) | 30 (8.1) | 0.95 (0.35–2.55) | 374 (48.1) | 26 (7) | 0.81 (0.30–2.19) | ||

| Indoor cooking | ||||||||

| Yes | 609 (80.9) | 46 (7.6) | 0.90 (0.46–1.74) | 0.75 | 628 (80.7) | 46 (7.3) | 1.00 (0.50–1.98) | 0.99 |

| No | 144 (19.1) | 12 (8.3) | 1 | 150 (19.3) | 11 (7.3) | 1 | ||

| Indoor kerosene use | ||||||||

| Yes | 88 (11.7) | 6 (6.8) | 0.86 (0.36–2.07) | 0.74 | 87 (11.2) | 6 (6.9) | 0.93 (0.39–2.23) | 0.87 |

| No | 665 (88.3) | 52 (7.8) | 1 | 691 (88.8) | 51 (7.4) | 1 | ||

| Types of roof | ||||||||

| Thatched | 578 (76.8) | 41 (7.1) | 0.71 (0.39–1.28) | 0.26 | 595 (76.5) | 42 (7.1) | 0.85 (0.46–1.57) | 0.61 |

| Corrugated iron | 175 (23.2) | 17 (9.7) | 1 | 183 (23.5) | 15 (8.2) | 1 | ||

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Reported wheeze- and eczema-ever at year 3 follow-up.

Likelihood ratio test.

P for trend.

Exclusive breastfeeding status at 2 months.

Any vaccination history at 2 months.

Table 2 shows that infantile symptoms of respiratory infections (cough, fast breathing, and fever) were commonly reported at age 2 months but not related to wheeze or eczema incidence. All three symptoms in the first year of life, however, were significantly positively associated with the incidence of wheeze between ages 1 and 3, but not eczema (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

PREVALENCE OF SYMPTOMS OF RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS IN EARLY LIFE IN THOSE WITH AND WITHOUT INCIDENT WHEEZE AND ECZEMA BETWEEN AGES 1 AND 3

| Wheeze Never at Age 1 (n = 756) | Eczema Never at Age 1 (n = 780) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms of Respiratory Infections | All Children | With Incident Wheeze | Without Incident Wheeze | P Value | All Children | With Incident Eczema | Without Incident Eczema | P Value |

| Respiratory infection symptoms at 2 mo, n (%) | ||||||||

| Cough | 298 (39.6) | 22 (37.9) | 276 (39.7) | 0.79 | 318 (40.9) | 23 (40.4) | 295 (40.9) | 0.93 |

| Fast breathing | 180 (23.9) | 15 (25.9) | 165 (23.7) | 0.72 | 192 (24.7) | 13 (22.8) | 197 (24.8) | 0.73 |

| Fever | 248 (32.9) | 21 (36.2) | 227 (32.7) | 0.58 | 275 (35.4) | 17 (29.8) | 258 (35.8) | 0.37 |

| Respiratory infection symptoms at 1 yr, n (%) | ||||||||

| Cough | 443 (58.6) | 41 (70.7) | 402 (57.6) | 0.05 | 487 (62.4) | 37 (64.9) | 450 (62.2) | 0.67 |

| Fast breathing | 251 (33.2) | 27 (46.6) | 224 (32.1) | 0.03 | 297 (38.1) | 24 (42.1) | 273 (37.8) | 0.52 |

| Fever | 581 (76.9) | 51 (87.9) | 530 (75.9) | 0.04 | 618 (79.2) | 48 (84.2) | 570 (78.8) | 0.34 |

Missing data on symptoms of respiratory infection at age 2 mo on three in wheeze-free cohort and two in eczema-free cohort.

Geohelminth infection at age 1 was found in only 4% of children, with hookworm being the most common infection (2.3%), followed by A. lumbricoides (1.4%) and T. trichiura (0.4%). The risk of new-onset wheeze was lower in those infected (3.6%) than uninfected (7.8%), but the 95% CI was wide and significance not reached (crude OR, 0.44 and 95% CI, 0.06–3.27 for any infection; OR, 0.80 and 95% CI, 0.10–6.16 for hookworm infection). Because only one infected child had incident wheeze, no further adjusted analysis could be performed. No children with geohelminth infection reported incident eczema, and therefore ORs could not be computed or further analysis performed.

Acetaminophen use in the first year of life was commonly reported (36% in wheeze cohort and 39% in eczema cohort), with around a quarter reporting use in the past month (Table 3). Use was significantly associated with the incidence of wheeze (P = 0.009), with risks increased in the one to three tablets per month group (adjusted OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.03–3.44) and the greater than or equal to four tablets per month group (adjusted OR, 7.25; 95% CI, 2.02–5.95) compared with the never-users. A significant trend across the categories of dose in the past month (zero, one to three, greater than four tablets) was also seen (P trend = 0.001). Further control for other potential confounders collected, including postnatal maternal acetaminophen use, which was strongly related to child's use (see Table E1), did not materially alter the associations. Use was seen to be associated with symptoms of respiratory infections in the first year of life (Table E1) and adjustment for these slightly reduced the strength of the wheeze association but overall significance remained (Table 3) (overall P = 0.014; P trend = 0.001). The population-attributable risk of wheezing associated with the use of acetaminophen in the first year of life (use in past month) was 20%. For eczema, the OR for use of acetaminophen in the past month was increased (adjusted OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 0.92–2.98) compared with never-use, but no overall significant association was seen (Table 3). Findings were similar when recent use of acetaminophen as reported at age 3 was examined, with a significant dose-dependent effect on incident wheeze (fully adjusted P trend = 0.01) but not eczema (Table E2).

TABLE 3.

UNIVARIATE AND MULTIVARIATE ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN CHILD'S USE OF ACETAMINOPHEN IN THE FIRST YEAR OF LIFE AND INCIDENT WHEEZE AND ECZEMA BETWEEN AGES 1 AND 3

| Outcome | Acetaminophen Use in the First Year of Life | Overall N (%) | New Disease N (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | P Value | Further Adjusted OR† (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incident wheeze (n = 756) | Never | 486 (64.3) | 31 (6.4) | 1 | 1 | 0.009‡ | 1 | 0.014‡ |

| Yes but not in the past month | 83 (11) | 4 (4.8) | 0.74 (0.26–2.16) | 0.73 (0.25–2.14) | 0.001§ | 0.70 (0.24–2.04) | 0.001§ | |

| 1–3 tablets per month | 175 (23.2) | 19 (10.7) | 1.79 (0.98–3.26) | 1.88 (1.03–3.44) | 1.77 (0.96–3.26) | |||

| ≥4 tablets per month | 12 (1.6) | 4 (33.3) | 7.34 (2.09–25.72) | 7.25 (2.02–25.95) | 6.78 (1.89–24.39) | |||

| Incident eczema (n = 780) | Never | 477 (61.3) | 30 (6.3) | 1 | 1 | 0.25‡ | 1 | 0.30‡ |

| Yes but not in the past month | 86 (11.1) | 6 (7) | 1.12 (0.45–2.77) | 1.17 (0.47–2.91) | 1.14 (0.45–2.87) | |||

| ≥1 tablet per month | 215 (27.6) | 21 (9.8) | 1.61 (0.90–2.89) | 1.66 (0.92–2.98) | 1.62 (0.89–2.96) |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

ORs adjusted for sex, urban rural residence, and maternal education.

ORs adjusted for child's sex, place of living, and maternal education and additionally adjusted for symptoms of respiratory infections in the first year of life.

Overall P value (likelihood ratio test).

P value for trend (computed for dose of acetaminophen intake in the past month: 0, 1–3, and ≥4 tablets).

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal birth cohort in Ethiopia, we have been able to look for the first time at the effect of acetaminophen use in infancy (first year of life) on the incidence of childhood allergic disease symptoms and found a positive dose–response association with incident wheeze but not eczema with a population-attributable risk of 20%. We have also explored effects of geohelminth infection in the first year of life, but small numbers resulted in insufficient power to determine independent effects on incident wheeze and eczema at this age, and any effect remains to be seen as the cohort matures and more children become infected.

The strengths of this study are the longitudinal design, ensuring that exposures precede the outcomes, and the high response rate and good retention of participants between birth and 3 years. In addition, the large number of demographic and lifestyle variables collected allowed us to control for potential confounders. Of particular concern was confounding by socioeconomic status, because this may influence access to acetaminophen. However, we found that none of our markers of social advantage and affluence (urban or rural residence, maternal education, and maternal occupation and income) were related to acetaminophen use and therefore the effects seen are unlikely to be caused by residual confounding by social advantage. Acetaminophen was found to be commonly used in our study population (use in first year of life reported in over one-third of infants), but because the information was not collected, we do not know specifically about the indications of acetaminophen use in these infants. However, it is likely to be used for the common causes of infant morbidity in Ethiopia, namely malaria, upper and lower respiratory tract infections, gastroenteritis and colitis, and fever of unknown origin (26). We therefore explored the possibility of confounding by indication, particularly that arising from acetaminophen being taken by children for respiratory tract infections in early life, who are also more susceptible to the subsequent development of allergic diseases (27). When we adjusted for the main symptoms of respiratory infections in the first year of life, the wheeze association reduced in magnitude slightly but remained highly statistically significant.

The possibility of reporting bias, introduced by the use of interview-led questionnaires, needs to be considered when interpreting our findings. We were unable to collect outcome and exposure data using daily diaries because the literacy level of many mothers was low. Instead, mothers were asked to recall symptoms since birth and poor recall may have led to a degree of error in our wheeze and eczema variables. Our observation of a large proportion of children with reported wheeze-ever at age 1 having a negative response to ever-wheeze at age 3 is likely to be explained by mothers not remembering wheeze symptoms experienced by their child as a baby but which then resolved. This transient wheeze phenotype is thought to be infection-related and more common in those born with small airways (28), and in our previous risk factor analysis of the cohort at age 1, evidence of such a phenotype was found (24). The implications of poor recall on our current findings are that some incident cases may have been missed if symptoms only occurred early in the 1- to 3-year follow-up period, although such nonpersistent cases are likely to those with mild disease. For eczema, although we have previously shown that the symptoms being reported seem to be linked to an allergic etiology (24), some degree of misclassification with scabies or other skin conditions cannot be ruled out. To ascertain a child's use of acetaminophen, mothers were asked about use in the first year of life at the 1-year follow-up, and additionally about consumption in the past month to minimize recall bias and quantify use. Because our previous qualitative and quantitative work in the same setting has shown that our study participants were able to distinguish different analgesics, and that most of the general population in the study area know acetaminophen to be different from aspirin (15, 29), reporting error is likely to be low.

An issue in previous studies has been the possibility that observed associations between acetaminophen and wheeze have arisen through aspirin avoidance in those with asthma. Although this is unlikely to confound our findings because of the fact that acetaminophen consumption preceded the outcome in our study, there is the possibility that parents with asthma may avoid giving their child aspirin and hence an association arises because children with genetic susceptibility are more likely to be given acetaminophen. However, we have previously established that only 1% of the population in the study area reported avoidance of aspirin because of asthma risk (29), making this an unlikely explanation for the observed association. Information on use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs that may be linked to asthma and allergic diseases (12) was not collected because they are not readily available or affordable in this rural community.

The acetaminophen and asthma hypothesis has attracted interest for more than a decade (19) and many studies, although primarily cross-sectional, have independently demonstrated an increased prevalence of asthma and other allergic conditions among acetaminophen users (8, 9, 11–19). Our current findings fit with our previous research in children and adults in the same Butajira study area, which reported a similar level of acetaminophen use (42% vs. 39% in the current study), and a significant dose-dependent association with wheeze (15). Findings from the large International Study for Asthma and Allergies in Children multicountry study of 205,487 6- to 7-year old children of a significant association between current and first year use of acetaminophen and the risk of asthma (13) also fit with our findings. However, both these cross-sectional studies reported significant associations with eczema, not seen in our current study, and effects on other allergic outcomes (13, 15). Prospective evidence has been limited to a handful of studies showing a positive relation between acetaminophen exposure in the intrauterine environment, particularly in late pregnancy, and the risk of wheeze but not eczema during childhood (8–11), and a single study looking at personal consumption, which was in adults not children, and reported a positive relation between acetaminophen use and adult-onset asthma in women (18). The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, for example, showed highly significant associations between frequent acetaminophen use in late pregnancy (most days/daily) and wheezing in children at age 30–42 months and later at age 69–81 months, although the ORs were not as large as those seen here (2.10 and 1.86, respectively) (8, 9). The reason why no prospective study, including ours, has found independent associations between acetaminophen use and eczema may be attributed to low statistical power or misclassification of eczema symptoms, or there may be no true effect and underlying mechanisms relate specifically to the lung.

Possible suggested mechanisms whereby acetaminophen intake might increase the risk of asthma and allergic diseases include the depletion of pulmonary glutathione concentration (30, 31) and the inhibition of basal INF-α and IL-6 secretion, predisposing the lung to epithelial damage, mast cell activation, excess mucus secretion, and bronchoconstriction (30, 31). The animal model used demonstrated that the lung was the first organ in which this depletion action persisted further potentiating other toxic products (32). Peterson and coworkers (33), using two immunologic animal models, suggest that depletion of glutathione decreased levels of Th1 cytokine responses thereby favoring allergenic patterns of Th2.

The hypothesis that geohelminth infections, which are highly prevalent in areas where allergy remains rare, may protect against asthma and allergic diseases has gained support from a range of independent studies, metaanalyses, and systematic reviews (5, 6). Although we found no significant associations in our study, the observed effects were in the expected direction, and our analyses were limited by insufficient statistical power as a result of the low prevalence of geohelminth infection in the first year of life and small numbers with the outcomes among the infected children. The low prevalence of geohelminths in children in this population is probably linked to a mass deworming strategy that started in 2006 in children under 5 years old in this area (34). We anticipate that as the cohort ages, more children will become infected and we will be better able to assess these associations.

In conclusion, this longitudinal study from a developing country birth cohort provides further support for an association between infantile use of acetaminophen and increased risk of incident wheeze, which is unlikely to be explained by aspirin avoidance, reverse causation, or confounding by indication. Because the use of acetaminophen preceded the outcomes, a causal explanation is increasingly likely. Further research is therefore needed, particularly randomized controlled trials and longitudinal birth cohort studies. We found no significant association between geohelminth exposure in the first year of life and risk of incident wheeze and eczema but were limited by low geohelminth prevalence. We intend to continue following-up these children, to further explore the temporal relationships between acetaminophen, geohelminth exposure, and allergic outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the mothers and children who participated in the birth cohort; the data collectors for their stamina during the field work; and the technicians of Aklilu Lemma Institute of Pathobiology for examining the stool samples.

Supported by Asthma UK (grant 07/036) and the Wellcome Trust (WT081504/Z/06/Z).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201006-0989OC on October 8, 2010

Author Disclosure: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Eder W, Ege MJ, von Mutius E. The asthma epidemic. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2226–2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel S, Jarvelin MR, Little M. Systematic review of worldwide variations of the prevalence of wheezing symptoms in children. Environ Health 2008;7:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asher MI, Montefort S, Bjorksten B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, Williams H. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicounty cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 2006;368:733–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strachan DP. Family size, infection and atopy: the first decade of the hygiene hypothesis. Thorax 2000;55:S2–S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leonardi-Bee J, Pritchard D, Britton J; Parasites in Asthma Collaboration. Asthma and current intestinal parasite infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:514–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flohr C, Quinnell RJ, Britton J. Do helminth parasites protect against atopy and allergic disease? Clin Exp Allergy 2009;39:20–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varner AE, Busse WW, Lemanske RF. Hypothesis: decreased use of pediatric aspirin has contributed to the increasing prevalence of childhood asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1998;81:347–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaheen SO, Newson RB, Sherriff A, Henderson AJ, Heron JE, Burney PGJ, Golding J; ALSPAC Study Team. Paracetamol use in pregnancy and wheezing in early childhood. Thorax 2002;57:958–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaheen SO, Newson RB, Henderson AJ, Headley JE, Stratton FD, Jones RW, Strachan DP. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and risk of asthma and elevated immunoglobulin E in childhood. Clin Exp Allergy 2005;35:18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rebordosa C, Kogevinas M, Sorensen HT, Olsen J. Pre-natal exposure to paracetamol and risk of wheezing and asthma in children: a birth cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:583–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Persky V, Piorkowski J, Hernandez E, Chavez N, Wagner-Cassanova C, Vergara C, Pelzel D, Enriquez R, Gutierrez S, Busso A. Prenatal exposure to acetaminophen and respiratory symptoms in the first year of life. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008;101:271–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lesko SM, Louik C, Vezina RM, Mitchell AA. Asthma morbidity after the short-term use of ibuprofen in children. Pediatrics 2002;109:e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beasley R, Clayton T, Crane J, von Mutius E, Lai CK, Montefort S, Stewart A; ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Association between paracetamol use in infancy and childhood, and risk of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in children aged 6–7 years: analysis from Phase Three of the ISAAC program. Lancet 2008;372:1039–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newson RB, Shaheen SO, Chinn S, Burney PG. Paracetamol sales and atopic disease in children and adults: an ecological analysis. Eur Respir J 2000;16:817–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davey G, Berhane Y, Duncan P, Aref-Adib G, Britton J, Venn A. Use of acetaminophen and the risk of self-reported allergic symptoms and skin sensitization in Butajira, Ethiopia. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;116:863–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKeever TM, Lewis SA, Smit HA, Burney P, Britton JR, Cassano PA. The association of acetaminophen, aspirin, and ibuprofen with respiratory disease and lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:966–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaheen SO, Sterne JAC, Songhurst CE, Burney PGJ. Frequent paracetamol use and asthma in adults. Thorax 2000;55:266–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barr RG, Wentowski CC, Curhan GC, Somers SC, Stampfer MJ, Schwartz J, Speizer FE, Camargo CA Jr. Prospective study of acetaminophen use and newly diagnosed asthma among women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;169:836–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farquhar H, Stewart A, Mitchell E, Crane J, Eyers S, Weatherall M, Beasley R. The role of paracetamol in the pathogenesis of asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2010;40:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eneli I, Sadri K, Camargo C, Barr RG. Acetaminophen and the risk of asthma. Chest 2005;127:604–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amberbir A, Medhin G, Alem A, Britton J, Davey G, Venn A. The role of paracetamol, geohelminths and other environmental exposures on the incidence of wheeze and eczema in an Ethiopian birth cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;181:A2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berhane Y, Wall S, Kebede D, Emmelin A, Enquselassie F, Byass P, Muhe L, Andersson T, Deyesssa N, Hogberg U, et al. Establishing an epidemiological field laboratory in rural areas-potential for public health research and interventions. Ethiop J Health Dev 1999;S13:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanlon C, Medhin G, Alem A, Tesfaye F, Lakew Z, Worku B, Dewey M, Araya M, Abdulahi A, Hughes M, et al. Impact of antenatal common mental disorders upon perinatal outcomes in Ethiopia: the P-MaMiE population-based cohort study. Trop Med Int Health 2009;14:156–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belyhun Y, Amberbir A, Medhin G, Erko B, Hanlon C, Venn A, Britton J, Davey G. Prevalence and risk factors of wheeze and eczema in one year old children: the Butajira birth cohort, Ethiopia. Clin Exp Allergy 2010;40:619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO. Basic laboratory methods in medical parasitology. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1991.

- 26.Federal Ministry of Health. Health and health related indicators. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2007.

- 27.Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, Bergmann R, Niggemann B, Sommerfeld C, Wahn U, and the MAS Group. Early childhood infectious diseases and the development of asthma up to school age: a birth cohort study. BMJ 2001;322:390–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Morgan WJ, The MAS Group. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. N Engl J Med 1995;332:133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duncan P, Aref-Adib G, Venn A, Britton J, Davey G. Use and misuse of aspirin in rural Ethiopia. East Afr Med J 2006;83:31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nuttall SL, Williams J, Kendall MJ. Does paracetamol cause asthma? J Clin Pharm Ther 2003;28:251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimova S, Hoet PHM, Dinsdale D, Nemery B. Acetaminophen decreases intracellular glutathione levels and modulates cytokine production in human alveolar macrophages and type II pneumocytes in vitro. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2005;37:1727–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Micheli L, Cerretani D, Fiaschi A, Gioorgi G, Romeo R, Runci RF. Effect of acetaminophen on glutathione levels in rat testis and lung. Environ Health Perspect 1994;102:63–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson JD, Herzenberg LA, Vasquez K, Waltenbaugh C. Glutathione levels in antigen-presenting cells modulate Th1 versus Th2 response patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95:3071–3076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Federal Ministry of Health. Guidelines for the Enhanced Outreach Strategy (EOS) for child survival interventions. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: MOH; 2004.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.