Abstract

Rationale: Damage to mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) by the production of reactive oxygen species during inflammatory states, such as sepsis, is repaired by poorly understood mechanisms.

Objectives: To test the hypothesis that the DNA repair enzyme, 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (OGG1), contributes to mtDNA repair in sepsis.

Methods: Using a well-characterized mouse model of Staphylococcus aureus sepsis, we analyzed molecular markers for mitochondrial biogenesis and OGG1 translocation into liver mitochondria as well as OGG1 mRNA expression at 0, 24, 48, and 72 hours after infection. The effects of OGG1 RNA silencing on mtDNA content were determined in control, tumor necrosis factor-α, and peptidoglycan-exposed rat hepatoma cells. Based on in situ analysis of the OGG1 promoter region, chromatin immunoprecipitation assays were performed for nuclear respiratory factor (NRF)-1 and NRF-2α GA-binding protein (GABP) binding to the promoter of OGG1.

Measurements and Main Results: Mice infected with 107 cfu S. aureus intraperitoneally demonstrated hepatic oxidative mtDNA damage and significantly lower hepatic mtDNA content as well as increased mitochondrial OGG1 protein and enzyme activity compared with control mice. The infection also caused increases in hepatic OGG1 transcript levels and NRF-1 and NRF-2α transcript and protein levels. A bioinformatics analysis of the Ogg1 gene locus identified several promoter sites containing NRF-1 and NRF-2α DNA binding motifs, and chromatin immunoprecipitation assays confirmed in situ binding of both transcription factors to the Ogg1 promoter within 24 hours of infection.

Conclusions: These studies identify OGG1 as an early mitochondrial response protein during sepsis under regulation by the NRF-1 and NRF-2α transcription factors that regulate mitochondrial biogenesis.

Keywords: mitochondrial DNA, 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase, nuclear respiratory factor-1, sepsis, reactive oxygen species

AT A GLANCE COMMENTARY.

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Multiple organ failure in sepsis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The molecular mechanisms of organ failure and the protective host responses to it are poorly understood.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This study examines the role of the mitochondrial DNA repair enzyme 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase in experimental sepsis and identifies novel transcriptional regulatory mechanisms and mitochondrial translocation of the active enzyme as an early part of coordinated activation of mitochondrial biogenesis involved in the organ recovery phase.

Multiple organ failure (MOF) from severe sepsis represents a significant global health burden that is increasing as the population ages. Sepsis is currently the 10th leading cause of death in the United States and since 1991 has accounted for more than $16 billion in annual healthcare expenditures (1, 2). Among a wide range of infections, Staphylococcus aureus is today the most common bacterial isolate (3). The mechanisms of MOF in sepsis are poorly understood in part because the innate intracellular responses acting to protect host cells and hence organs from intracellular damage are incompletely defined. A deeper understanding of these mechanisms is necessary to develop new therapies to prevent and treat MOF and to improve survival from sepsis syndrome.

Intracellular homeostasis and organ function require energy in the form of ATP generated primarily through the mitochondrial processes of respiration and oxidative phosphorylation (4). Respiration requires oxygen and carbon substrates but also produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) as a by-product (5); the latter process accelerates during inflammation and can damage mitochondrial proteins, lipids, and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is not afforded protection by histones (3, 4). In sepsis, ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) overproduction and mitochondrial damage are well-known consequences of the host response to inflammation (5–7).

Mitochondrial DNA is more easily damaged by ROS/RNS than nuclear DNA due to proximity to sites of ROS/RNS generation (8). One of the major oxidative effects on mtDNA is the formation of stable 8-hydroxyguanine (8-OHdG) (9), which if not excised and the genome repaired, permits base mismatch in the form of G:C to T:A transversions leading to mtDNA mutations (10, 11). Enzymatic mechanisms have evolved to remove 8-OHdG from DNA by base excision repair (BER) pathways, which are functionally present both in mitochondria and in the nucleus (12). The 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (OGG1) is a BER enzyme that plays a pivotal role in removing 8-OHdG from both nuclear and mtDNA (13, 14), but the role of mitochondrial OGG1, especially its timing and transcriptional regulation, has not been evaluated during sepsis.

The Ogg1 gene encodes four variants, and three of the proteins can be found in mitochondria (15, 16). Prior studies have shown that oxidative stress from sepsis-producing bacterial products such as LPS lead to significant but reversible mtDNA depletion, but whether OGG1 participates in mtDNA repair under such conditions is unknown (17). Previously, OGG1 has been shown to protect against ROS/RNS-induced apoptosis; for instance, targeting human OGG1 (hOGG1) to oligodendrocytes protects against cytokine-induced apoptosis (14). Similar protective effects of hOGG1 have been seen in INS-1 cells during free fatty acid–induced apoptosis (18). Because sepsis induces significant oxidative mtDNA damage, we tested the hypothesis that OGG1 accumulates in mitochondria in the early phase of sepsis to support mtDNA fidelity as part of the coordinated bigenomic response to maintain mitochondrial function through mitochondrial biogenesis.

Although activation of mitochondrial biogenesis is an important step in protection from organ failure in sepsis, no detailed mechanisms for resolution of mtDNA damage have been elucidated (19, 20). mtDNA integrity is required for mitochondrial biogenesis, and the success of the bigenomic program depends on high-fidelity mtDNA replication. The transcriptional program for mitochondrial biogenesis also requires the expression and nuclear translocation of the nuclear respiratory factor (NRF)-1 and NRF-2 transcription factors and appropriate coactivators. Whether the activation of this transcriptional program in sepsis also activates Ogg1 has not been reported and is the focus of this study.

METHODS

Materials

Antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA) or Genox (Baltimore, MD) (8-OHdG). NRF-1, NRF-2, and mitochondrial transcription factor-A (Tfam) antibodies were developed and characterized in our laboratory (21–23). Secondary antibodies were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) or Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Small interfering (si)RNA oligonucleotides were obtained from Ambion (Austin, TX).

Animals

The animal component was approved by Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male C57Bl6/J mice were obtained from Jackson (Bar Harbor, ME) and used at 12 to 16 weeks old. S. aureus clots were prepared and implanted abdominally as described (19) at a 107-cfu dose. Because our goal was to discover early enzyme recruitment into the mitochondria, we chose a dose of organisms that leads to minimal mortality by 3 days but results in 30 to 50% mortality by 7 days after infection. Mice that are alive by 7 days after implantation usually recover. Mice were monitored daily and killed at the desired times using isoflurane. Livers from three mice at each time were harvested immediately and divided to make total, mitochondrial, and nuclear protein fractions as described (21). The mitochondrial pellet was stored in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer with protease inhibitors at −80°C until they were used for Western blot analysis.

mtDNA Copy Number and Respiratory Proteins

mtDNA was quantified by SYBR green quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using an ABI Prism 7000 sequence-detector system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). mtDNA-encoded cytochrome c oxidase subunit I and NADH dehydrogenase subunit I mRNA were quantified by reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR and normalized to nuclear-encoded 18S and/or glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (24).

Real-Time RT-PCR

qRT-PCR was performed using an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System with TaqMan gene expression and premix assays for IL-6, Mm00446190_m1; tumor necrosis factor (TNF), Mm00443258_m1; Tfam, Mm01148667_m1; OGG1, Mm01184571_g1; NRF-1, Mm01135607_m1; NRF-2, Mm00484597_m1 (Applied Biosystems). 18S rRNA served as an endogenous control (24). Quantification of gene expression was determined by the comparative threshold cycle CT and relative quantification (RQ) method.

Protein Immunomethods and Assay

Liver total and mitochondrial protein were measured by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). For Western analysis, 20 μg protein samples were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate– polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using 8% or gradient gels. The separated protein was transferred to Immobilon P membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and blocked with 4% nonfat dry milk in TBST (Sigma). Membranes were incubated at 4°C overnight with polyclonal rabbit antibodies for phospho-Akt (1:1,000), Akt (1:1,000), OGG1 (1:1,000), porin (1:1,000), NRF-1 (1:1,000), NRF-2 (GA-binding protein [GABP]); 1:1,000, heme oxygenase (HO)-1 (1:100), histone (1:1,000), and Tfam (1:1,000). After application of primary antibodies, each membrane was washed with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-goat antibody, washed again, and developed using ECL chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The blots were digitized and the protein density quantified in the mid-dynamic range relative to tubulin, porin, or histone (BioRad ImageQuant software, Hercules, CA).

For immunohistochemistry, 4-μm sections of 10% formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded liver were immunolabeled with primary antibodies to 8-OHdG and OGG1; immunofluorescence was quantified as described (21, 22).

OGG1 Excision Assay

Liver mitochondria were used in a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-based OGG1 cleavage assay as described (25). Oligonucleotides were wild-type 5′FITC-ATACGCATATACCGCT(G)TCGGCCGATCTCCGAT8-oxo-G, 5′FITC-ATACGCATATACCGCT(8-oxo-G)TCGGCCGATCTCCGAT, and complementary 5′ATCGGAGATCGGCCGA(C)GGCGGTATATGCGTAT synthesized by Midlands and purified by affinity column (Sigma). Fifty micrograms of mitochondrial protein was incubated with 20 pmol of DS oligonucleotides for 4 hours and the reaction was stopped on ice. The products were separated on 20% acrylamide/7 M urea gels, and the gels were scanned on a Typhoon 9410 scanner (488 nm excitation/520 nm emission). A 10/60 oligonucleotide ladder (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) was used to assess product nucleotide size after Gelstar staining (Lonza, Switzerland).

Cell Culture and RNA Silencing

Rat H4IIE hepatoma cells were cultured in RPMI media at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 95% air. Cells were transfected with OGG1 siRNA or scrambled oligonucleotides as controls (Ambion–Applied Biosystems) using the FuGene HD transfection reagent (Roche, Madison, WI). Cells were exposed to 10 ng/ml peptidoglycan and TNF-α for 24 hours and mtDNA copy number was determined.

Bioinformatics

The mouse and human Ogg1 loci were aligned, and the DNA sequence homology was computed with the web-based rVISTA (www.gsd.lbl.gov/vista) (26). Promoter analysis was performed with consensus sequences for transcription factor binding located with DNASIS (Hitachi Software; Alameda, CA) and confirmed with MatInspector (Genomatix Software; München, Germany). Putative NRF-1 or NRF-2 binding sites of 92 to 100% homology were identified in the Ogg1 promoter region (Ensembl Gene ID ENSMUSG00000030271).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assays

The assay was performed with a commercial assay kit (chromatin immunoprecipitation [ChIP]-IT kit; Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) using a minor protocol modification (21). Cold, finely diced liver (200 mg) was suspended in phosphate-buffered saline and cross-linked in 1% (v/v) formaldehyde at room temperature. Reactions were stopped with glycine (0.125 M), the samples pelleted twice by centrifugation, and the final pellet suspended in ChIP buffer. Genomic DNA was sheared on ice using a Branson 250 sonifier and lysates were tumbled overnight at 4°C with salmon sperm DNA/protein A-agarose with anti-RNA polymerase II (Santa Cruz), anti–NRF-1, anti–NRF-2α antibodies, or rabbit IgG. Complexes were precipitated, washed, eluted, and adjusted to 200 mM NaCl and cross-linking reversed. DNA was purified using a PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). The samples were evaluated for NRF-1 or NRF-2α enrichment using PCR primers for regions upstream of the mouse Ogg1 genes (sequences available on request). The efficiency of each PCR primer was determined using input DNA (21, 24, 27).

Data Analysis

Each time point for analysis contained at least three samples from three mice per group for statistical analysis. Grouped data are expressed as means ± SD. Differences between groups were determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey analysis using Sigma Stat and Sigma Plot software (Systat Software Inc; Chicago, IL); P less than or equal to 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

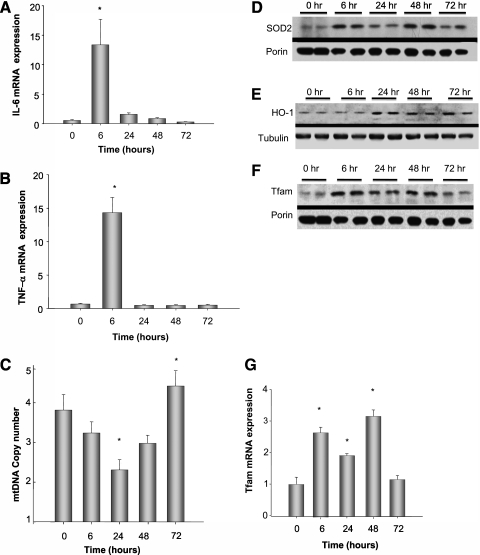

To determine the effect of the peritoneal sepsis model on liver-specific cytokine induction, liver mRNA was assayed for IL-6 and TNF-α by real-time PCR. The mRNA expression levels for both cytokines increased acutely 6 hours after clot implantation but returned to baseline by 24 hours (Figures 1A and 1B). Given the close relationship between mtDNA transcription and the tissue's capacity for oxidative phosphorylation, oxidized mtDNA accumulation and interference with template activity may contribute to the metabolic and bioenergetic deficits of bacterial sepsis and the reversible decline in mtDNA copy number during S. aureus peritonitis at 106 cfu (19). To extend these observations to a larger organism burden, C57BL/6J mice were infected with S. aureus at 107 cfu, which increased mortality to 30 to 50% by 7 days, but only approximately 5% by 3 days (data not shown). To avoid a survival bias, and to focus on the early events of mtDNA repair, mice were randomly evaluated at multiple times in the first 72 hours after infection. We evaluated mtDNA in these mice beginning at 6 hours after infection and found the steepest decline in copy number at 24 hours. Copy number returned to above baseline by 72 hours after infection, suggesting active mtDNA replication (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α mRNA expression, mitochondrial (mt)DNA copy number, antioxidant enzyme expression, and markers of mtDNA replication during Staphylococcus aureus peritonitis in mice. (A, B) Pooled analysis of three mice per time point of IL-6 and TNF-α mRNA expression by real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction in liver tissue from S. aureus–infected mice. Cytokine levels increased significantly by 6 hours and returned toward baseline by 24 hours. (C) mtDNA copy number amount significantly decreased to its lowest amount 24 hours after infection and significantly increased above baseline at 72 hours after infection, *P < 0.05 by analysis of variance follow-up by Tukey analysis. (D) Representative Western blot of the mitochondrial protein fraction from two mice at each time point for superoxide dismutase (SOD2) compared with porin. SOD2 increased at 6 hours after infection and remained elevated for 72 hours. (E) Representative Western blot of whole cell lysate for HO-1 expression compared with tubulin. HO-1 increased at 24 hours after infection. (G) Mitochondrial transcription factor-A (Tfam) mRNA levels in liver tissue from S. aureus–infected mice. Tfam levels increase significantly at 6 hours and return to baseline by 72 hours after infection, *P < 0.05 by analysis of variance. (F) Representative Western analysis of the mitochondrial fraction for Tfam protein demonstrating an increase in mitochondrial Tfam at 6 hours and remaining elevated at least for 48 hours in the mitochondrial fraction.

Because antioxidant enzymes are critical to mitochondrial protection from oxidative stress, we examined antioxidant enzyme profiles in the liver. By Western analysis, we found a significant increase in hepatic superoxide dismutase 2 and HO-1 protein expression after the S. aureus infection (Figures 1D and 1E). In addition, Tfam was checked, and pronounced increases were found in both cellular Tfam mRNA levels and protein accumulation in the mitochondria. (Figures 1F and 1G).

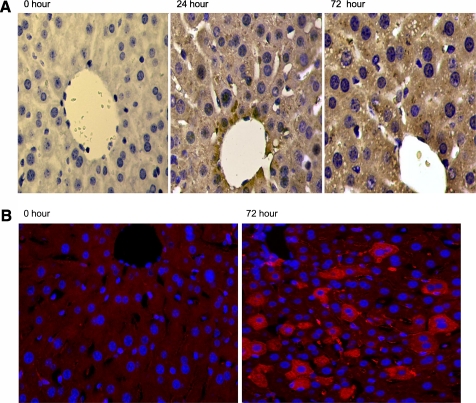

To assess the ROS activity acting on mtDNA in sepsis, we evaluated 8-OHdG products by immunohistochemistry using antibodies against 8-OHdG. Hepatic mtDNA oxidation was evaluated in mice at 0, 24, and 72 hours after intraperitoneal implantation of fibrin clots containing 106 and 107 cfu of S. aureus. Minimal staining indicating 8-OHdG labeling was visible in hepatocytes of control liver, but the liver sections from septic mice stained heavily in the cytoplasm with a punctuate, granular pattern, suggesting accumulation of 8-OHdG adducts in the mitochondrial compartment, although some nuclear staining was also present (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Hepatic 8-hydroxyguanine (8-OHdG) and 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (OGG1) staining in live S. aureus peritonitis in mice. (A) Left to right, hepatic 8-OHdG staining in C57Bl6 mice at time 0, 24, and 72 hours after intraperitoneal implantation of fibrin clot containing Staphylococcus aureus. 8-OHdG staining is brown and appears primarily as punctuate granules within the cytoplasm, suggesting mitochondrial DNA staining after infection. (B) Hepatic immunochemistry for OGG1 in mice infected with S. aureus. OGG1 by fluorescence immunohistochemistry (red staining) is increased in the liver at 72 hours after infection compared with control level. In this setting the bulk of the OGG1 is found in the cytoplasm.

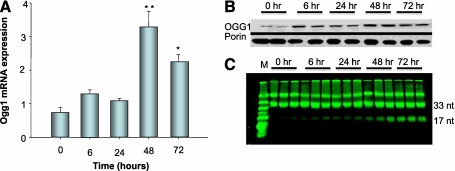

To determine if OGG1, which repairs mtDNA 8-OHdG adducts, is up-regulated and translocates to the mitochondria during sepsis, hepatic immunohistochemistry for OGG1 was performed. Compared with controls, liver sections from infected mice displayed an impressive cytoplasmic, mostly mitochondrial, pattern of red fluorescence staining at 72 hours (Figure 2B). Interestingly, not all cells stained for OGG1 suggesting a differential expression of OGG1 within regions of the whole organ. To confirm that OGG1 mitochondrial protein content and mRNA levels in the liver increase during the S. aureus infection, we performed real-time RT-PCR on total RNA and Western analysis for OGG1 protein on mitochondrial subcellular fractions. OGG1 mRNA expression levels revealed a sharp increase at 48 hours after infection (Figure 3A). OGG1 protein levels increased in the liver mitochondrial fraction as early as 6 hours with a sharp peak at 48 hours that was sustained at 72 hours after infection (Figure 3B). However, a similar increase of OGG1 within whole cell lysate from the liver was not found (data not shown), suggesting that the overall increase in the mitochondrial protein is a result of increased recruitment from the cytoplasm followed later by increases in total cell protein as seen by immunohistochemistry. These increases in OGG1 mRNA and mitochondrial protein suggest that the mitochondrial genome has been compromised by the S. aureus infection. The OGG1 activity assay demonstrated increases in 8-OHdG excision activity beginning at 6 hours and persisting for at least 72 hours (Figure 3C), consistent with our Western and histological findings. Taken together, this evidence implies that mtDNA repair processes and mitochondrial biogenesis are operating in concert to maintain mtDNA copy number.

Figure 3.

Analysis of hepatic Ogg1 in control and S. aureus–infected mice. (A) Pooled analysis of three mice at each time point of real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction for Ogg1 expression in liver tissues and indicates that transcript levels reached a peak 48 hours after infection and remained elevated at 72 hours; *P < 0.05 by analysis of variance with follow-up by Tukey analysis. (B) Representative Western blot from two mice for mitochondrial 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (OGG1) protein relative to porin. OGG1 protein increased within the mitochondrial fraction compared with porin within 6 hours of infection and remained elevated at 72 hours. Western analysis is shown for two mice at each time point; however, pooled data from three mice were used for statistical significance, which was present beginning 6 hours after infection (data not shown). (C) OGG1 excision assay of the liver mitochondrial fraction from S. aureus–infected mice against fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled 8-hydroxyguanine oligonucleotides. The samples were done in triplicate and show increased excision activity as demonstrated by increased 17mer nucleotide beginning at 6 hours and remaining elevated for at least 72 hours.

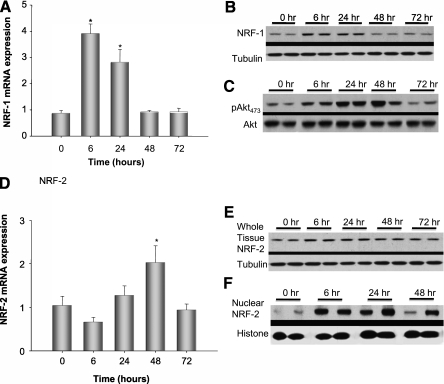

The NRF-1 and NRF-2 transcription factors are necessary for the coordinated nuclear–mitochondrial gene expression required to carry out mitochondrial biogenesis. Therefore, transcript and protein levels for NRF-1 and NRF-2 (GABP in mice) were checked after S. aureus infection along with the activation of Akt by serine 473 phosphorylation, necessary for NRF-1 nuclear translocation (Figures 4A–4E). NRF-1 mRNA and protein increased at 6 hours and remain elevated for at least 24 hours (Figures 4A and 4B). Akt activation by Western blot, measured as the ratio of total to phosphorylated Ser473 Akt, was activated by 6 hours and remained activated for 48 hours after infection (Figure 4C). Meanwhile, NRF-2 mRNA and protein increased by 6 hours and remained elevated for 48 hours; NRF-2 protein increased more significantly within the nuclear fraction than the whole cell lysate, suggesting translocation into the nucleus (Figures 4D–4F).

Figure 4.

Markers of hepatic mitochondrial biogenesis by real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction and Western blot analysis. (A) Pooled analysis of three mice at each time point for nuclear respiratory factor (NRF)-1 transcript levels by real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction. NRF-1 mRNA increased significantly by 6 hours and decreased by 48 hours after infection, *P < 0.05 by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey analysis. (B) Representative Western analysis from two mice per time point for NRF-1 relative to tubulin. NRF-1 protein, similar to mRNA expression, increased at 6 hours and decreased to baseline by 48 hours after infection. (C) Shows that Akt Ser473 phosphorylation by Western analysis is significantly increased by 6 hours after Staphylococcus aureus infection and sustained for at least 48 hours after infection. (D) Analysis of liver NRF-2 mRNA expression from the infected mice, *P < 0.05 by ANOVA. (E) Representative Western blot from two mice per time point for hepatic NRF-2. NRF-2 remained elevated even at 48 hours after infection. (F) Representative Western blot of NRF-2 from liver nuclear isolates. The increase in nuclear NRF-2 at 24 hours was more pronounced than in whole cell lysates. Three mice were used for each time point and statistical significance determined by ANOVA (data not shown). Representative Western blots from two mice are shown at each time point.

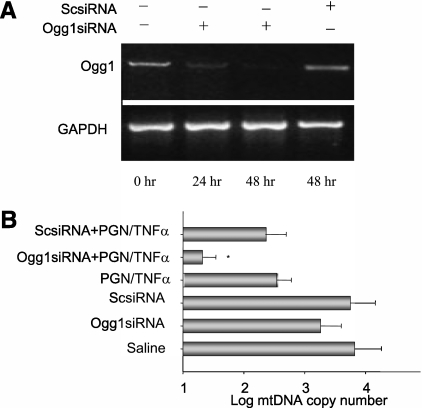

To determine if OGG1 is required to maintain mtDNA copy number in response to Toll-like receptor-2 activation and sepsis, we used siRNA to silence OGG1 in rat hepatoma cells. Cells were exposed to siOGG1 for 48 hours and then exposed to peptidoglycan and TNF-α for 24 hours. Figure 5A shows the transient loss of the Ogg1 transcript in the siRNA-treated cells relative to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Next, we demonstrated that peptidoglycan/TNF-α exposure reduced mtDNA copy number over 24 hours (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Ogg1 silencing in rat hepatoma cells. (A) Semiquantitative mRNA evaluation of rat hepatoma cells transfected with 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (OGG1) small interfering (si)RNA demonstrating decreased OGG1 mRNA levels compared with a scrambled siRNA control. OGG1 improves mitochondrial (mt)DNA copy number on exposure to the Toll-like receptor agonist, peptidoglycan (PGN), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. (B) Decreased mtDNA copy number in rat hepatoma cells transfected with siOGG1 and stimulated with peptidoglycan and TNF-α, *P < 0.05. GAPDH = glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

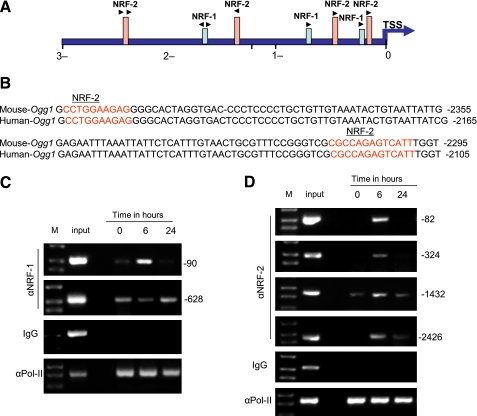

As Ogg1 mRNA levels increase during S. aureus sepsis, we examined whether sepsis directly stimulates Ogg1 gene transcription by NRF-1 and NRF-2 transcription factor binding to the Ogg1 promoter region. We performed a bioinformatics search for NRF-1 and NRF-2 binding sequences on the Ogg1 locus using rVISTA to identify interspecies-conserved sequences via linkage to the most widely used database, TRANSFAC. We also used in silico analysis of the proximal 3.0 kb of the Ogg1 5′UTR (DNAsis and Genmatox) in the mouse and human to identify potential NRF-1 or NRF-2 motifs within the Ogg1 5′-promoter sequence. Figures 6A and 6B show a diagram of the Ogg1 gene along with expansion of the human/mouse conserved region. The upstream region located at −120 to −1492 of Ogg1 transcription start site bears several sequences having a high probability of serving as NRF-1 and NRF-2 cis-acting promoter elements. The region between −2415 and −2295 in the mouse and −2225 and −2105 in human is highly conserved and harbors two NRF-2 consensus motifs that share 100% identity with the canonical NRF-2 in the two species. This suggested that NRF-1 and NRF-2 are particularly important for Ogg1 gene regulation.

Figure 6.

In silico and chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis of Ogg1 promoter site for nuclear respiratory factor (NRF)-1 and NRF-2α. NRF-1 and NRF-2α consensus site binding motifs were found for Ogg1 at 3 kb from the transcription start site. (A, B) Indicate the NRF-2α site within the Ogg1 promoter that is conserved between mice and humans. (C, D) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays of liver nuclei at time 0, 24, and 48 hours for NRF-1 and NRF-2α binding on the Ogg1 promoter after Staphylococcus aureus infection.

To verify NRF-1 and NRF-2 interactions with Ogg1 in situ, ChIP assays were performed in liver nuclear extracts. In S. aureus–treated mice, NRF-1 selectively bound to region −20 to −199 and −563 to −669 in the Ogg1 promoter. NRF-1 occupancy was only detected at 6 hours in the −20 to −199 site and appeared to decrease at 6 hours and then increase again by 24 hours at the −563 to −669 site (Figure 6C), suggesting that more than one mechanism is differentially regulating promoter DNA binding at various time points.

Next, ChIP assays were performed for NRF-2 binding with Ogg1 in liver nuclear extracts from S. aureus–infected and uninfected mice. PCR targeting the Ogg1 promoter region around the putative NRF-2 binding site was performed in parallel with input chromatin (i.e., before immunoprecipitation) used as a control for PCR efficiency. The proximal Ogg1 promoter region showed increases in NRF-2 occupancy after S. aureus infection, especially at 6 hours at the −45 to −160, −178 to −402, −1334 to −1583, and −2330 to −2608 sites (Figure 6D). Ogg1 promoter occupancy by NRF-1 and NRF-2 was accompanied by increased Pol-II recruitment, indicative of enhanced initiation of transcription. This is the first evidence that NRF-1 and NRF-2 regulate not only nuclear-encoded genes for mtDNA transcription and replication but also genes involved in the maintenance of mtDNA genomic integrity.

DISCUSSION

The hypothesis that OGG1 translocates to the mitochondria in the early phase of the response to S. aureus infection is based on the observed restoration of normal mtDNA copy number as part of the coordinated bigenomic response of mitochondrial biogenesis after sepsis-induced damage. This report provides the first evidence that an active mtDNA repair enzyme, OGG1, translocates promptly to the mitochondria during sepsis and that it supports maintenance of mtDNA copy number after activation of Toll-like receptor-2–mediated immune signaling in a liver cell line. Furthermore, Ogg1 is under transcriptional regulation by the NRF-1 and NRF-2 transcription factors, which are both up-regulated by sepsis. These data imply that NRF-1 and NRF-2, in addition to their roles in the regulation of nuclear-encoded genes for mitochondrial DNA transcription and replication, coordinate the BER pathway through Ogg1 transcriptional regulation that maintains mtDNA integrity during sepsis.

ROS production, especially superoxide anion and peroxynitrite, contribute to cell and organ injury in sepsis (23). In experimental sepsis models, increased ROS levels impair mitochondrial function, oxidize mitochondrial proteins, and damage organelle ultrastructure (7, 28, 29). In a sublethal rat model of LPS exposure, we have reported that mtDNA copy number is depleted in a reversible fashion. An LPS-induced mtDNA deletion in a G:C rich area near the D-loop occurred in the liver at 1 day postexposure, but the deletion was cleared and mtDNA copy number returned to baseline by 5 days, suggesting the recruitment of active DNA repair processes for oxidized mtDNA (17), although no specific mechanism was found.

BER of mtDNA, especially oxidized 8-oxoguanine DNA products (8-oxodG or 8-OHdG), is performed by the OGG1 protein, an 8-oxodeoxyguanine glycosylase, also called N-glycosylase/DNA lyase. Base excision repair studies in Ogg1-deficient mice suggest that OGG1 is responsible for more than 95% of BER, including BER 8-OHdG products of mtDNA (13, 30). Overexpression of human OGG1 in mitochondria of INS-1 cells has been shown to be protective from free fatty acid–induced mtDNA damage (18). The levels of mitochondrial-associated OGG1 are also higher in the livers of old mice compared with young mice; however, the protein appears to be associated with the outer mitochondrial membrane of old mice and not actively imported into the matrix as in young mice, which may contribute to the increased levels of 8-OHdG in mtDNA associated with aging (28). If OGG1 function is not as efficient in older compared with younger individuals or is not actively recruited into the matrix in response to mtDNA damage, this may play a role in the mtDNA depletion of severe sepsis. Furthermore, Ogg1 gene mutations are associated with tumorigenesis (29), indicating the critical importance of the enzyme to cellular homeostasis. Future studies in Ogg1 knockout mice in sepsis should be considered, but would require cautious interpretation because of the complex nuclear and mitochondrial roles of the enzyme (12).

It has been established that mitochondrial biogenesis is activated in mice that survive S. aureus sepsis and that mitochondrial biogenesis responds to increased mitochondrial ROS production in liver cells through a pathway that involves Akt-Ser473 phosphorylation of NRF-1 (24). NRF-1, a potent transcriptional activator of Tfam and the mitochondrial DNA polymerase (Polγ), is essential for mtDNA transcription and replication (19, 31, 32). This study confirms that Akt activation in conjunction with NRF-1 expression is associated with Tfam importation into the mitochondria during S. aureus sepsis, but newly demonstrates that NRF-1 and NRF-2 serve as active cis-acting DNA binding elements in the promoter region of Ogg1 and that mitochondrial OGG1 protein levels increase in association with restoration of hepatic mtDNA copy number. This is the first direct evidence that NRF-1 and NRF-2, as part of a major transcriptional program to support mitochondrial biogenesis during inflammation, includes the transcriptional regulation of an enzyme known to protect mtDNA from oxidative degradation. It is intriguing that the NRF-1 and NRF-2 DNA binding profiles for the proximal Ogg1 promoter region are significantly different by ChIP assay, implying that there are differential functions for the downstream mRNA translation and protein localization of OGG1. This observation however, will require further work.

It is important to put mitochondrial recruitment of OGG1 into the context of ongoing sepsis. Based on the available information on the other processes discussed above, an inability to import OGG1 to mitochondria would be expected to impair cell survival as well as impair cell proliferation, both of which are important to organ function in sepsis. It is clear that oxidative damage to mtDNA is associated with a higher susceptibility to extrinsic apoptosis in human lymphocytes (30), but moreover, it is also likely that intrinsic apoptosis would be activated by the failure to properly repair, transcribe, and replicate mtDNA during the metabolic stress of sepsis.

In summary, we have evaluated mtDNA repair during S. aureus sepsis in mice and for the first time demonstrate that active OGG1 repair enzyme is rapidly recruited to the mitochondria, presumably to ensure mtDNA fidelity and integrity. This process appears to be part of the coordinated program of mitochondrial biogenesis under the transcriptional control of NRF-1 and NRF-2. Future efforts to discern the actual molecular mechanisms responsible for mtDNA repair enzyme importation into the mitochondrial matrix may yield potential future targets for improving the host response to sepsis and for the prevention of organ dysfunction associated with mitochondrial damage.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lynn Teatro, Martha Salinas, and Craig Marshal for technical assistance.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants T32GM008600 (R.R.B.) and R01 AI0664789 (C.A.P.), and the Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200911-1709OC on August 23, 2010

Author Disclosure: R.R.B. received a sponsored grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for more than $100,001. H.B.S. received a sponsored grant from NIH for more than $100,001. P.F. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. K.W.W. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. M.S.C. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. N.C.M. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. C.M.W. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. T.E.S. received funding from Duke University MSTP (funded by NIH) for $10,001–$50,000. C.A.P. received a sponsored grant from NIH for more than $100,000.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 2001;29:1303–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton BE, Minino AM, Martin JA, Kochanek KD, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2005. Pediatrics 2007;119:345–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM, Ames BN. Oxidative damage and mitochondrial decay in aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:10771–10778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raha S, Robinson BH. Mitochondria, oxygen free radicals, disease and ageing. Trends Biochem Sci 2000;25:502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor DE, Kantrow SP, Piantadosi CA. Mitochondrial respiration after sepsis and prolonged hypoxia. Am J Physiol 1998;275:L139–L144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantrow SP, Taylor DE, Carraway MS, Piantadosi CA. Oxidative metabolism in rat hepatocytes and mitochondria during sepsis. Arch Biochem Biophys 1997;345:278–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor DE, Ghio AJ, Piantadosi CA. Reactive oxygen species produced by liver mitochondria of rats in sepsis. Arch Biochem Biophys 1995;316:70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anson RM, Hudson E, Bohr VA. Mitochondrial endogenous oxidative damage has been overestimated. FASEB J 2000;14:355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindahl T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature 1993;362:709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasai H, Nishimura S. Hydroxylation of deoxyguanosine at the C-8 position by ascorbic acid and other reducing agents. Nucleic Acids Res 1984;12:2137–2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osiewacz HD. Mitochondrial functions and aging. Gene 2002;286:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dianov GL, Souza-Pinto N, Nyaga SG, Thybo T, Stevnsner T, Bohr VA. Base excision repair in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 2001;68:285–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Souza-Pinto NC, Eide L, Hogue BA, Thybo T, Stevnsner T, Seeberg E, Klungland A, Bohr VA. Repair of 8-oxodeoxyguanosine lesions in mitochondrial DNA depends on the oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (OGG1) gene and 8-oxoguanine accumulates in the mitochondrial DNA of OGG1-defective mice. Cancer Res 2001;61:5378–5381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobson AW, Xu Y, Kelley MR, LeDoux SP, Wilson GL. Enhanced mitochondrial DNA repair and cellular survival after oxidative stress by targeting the human 8-oxoguanine glycosylase repair enzyme to mitochondria. J Biol Chem 2000;275:37518–37523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radicella JP, Dherin C, Desmaze C, Fox MS, Boiteux S. Cloning and characterization of hOGG1, a human homolog of the OGG1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997;94:8010–8015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takao M, Aburatani H, Kobayashi K, Yasui A. Mitochondrial targeting of human DNA glycosylases for repair of oxidative DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res 1998;26:2917–2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suliman HB, Carraway MS, Piantadosi CA. Postlipopolysaccharide oxidative damage of mitochondrial DNA. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:570–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rachek LI, Thornley NP, Grishko VI, LeDoux SP, Wilson GL. Protection of INS-1 cells from free fatty acid-induced apoptosis by targeting hOGG1 to mitochondria. Diabetes 2006;55:1022–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haden DW, Suliman HB, Carraway MS, Welty-Wolf KE, Ali AS, Shitara H, Yonekawa H, Piantadosi CA. Mitochondrial biogenesis restores oxidative metabolism during Staphylococcus aureus sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:768–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suliman HB, Welty-Wolf KE, Carraway MS, Schwartz DA, Hollingsworth JW, Piantadosi CA. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates mitochondrial DNA damage and biogenic responses after heat-inactivated E. coli. FASEB J 2005;19:1531–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suliman HB, Carraway MS, Ali AS, Reynolds CM, Welty-Wolf KE, Piantadosi CA. The CO/HO system reverses inhibition of mitochondrial biogenesis and prevents murine doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest 2007;117:3730–3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suliman HB, Carraway MS, Tatro LG, Piantadosi CA. A new activating role for CO in cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis. J Cell Sci 2007;120:299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piantadosi CA, Suliman HB. Mitochondrial transcription factor A induction by redox activation of nuclear respiratory factor 1. J Biol Chem 2006;281:324–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piantadosi CA, Carraway MS, Babiker A, Suliman HB. Heme oxygenase-1 regulates cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis via NRF2-mediated transcriptional control of nuclear respiratory factor-1. Circ Res 2008;103:1232–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ballal R, Cheema A, Ahmad W, Rosen EM, Saha T. Fluorescent oligonucleotides can serve as suitable alternatives to radiolabeled oligonucleotides. J Biomol Tech 2009;20:190–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuji-Takayama K, Suzuki M, Yamamoto M, Harashima A, Okochi A, Otani T, Inoue T, Sugimoto A, Toraya T, Takeuchi M, et al. The production of IL-10 by human regulatory T cells is enhanced by IL-2 through a STAT5-responsive intronic enhancer in the IL-10 locus. J Immunol 2008;181:3897–3905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piantadosi CA, Suliman HB. Transcriptional regulation of SDHa flavoprotein by nuclear respiratory factor-1 prevents pseudo-hypoxia in aerobic cardiac cells. J Biol Chem 2008;283:10967–10977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szczesny B, Hazra TK, Papaconstantinou J, Mitra S, Boldogh I. Age-dependent deficiency in import of mitochondrial DNA glycosylases required for repair of oxidatively damaged bases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:10670–10675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gangwar R, Ahirwar D, Mandhani A, Mittal RD. Do DNA repair genes OGG1, XRCC3 and XRCC7 have an impact on susceptibility to bladder cancer in the North Indian population? Mutat Res 2009.680:56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollins DL, Suliman HB, Piantadosi CA, Carraway MS. Glutathione regulates susceptibility to oxidant-induced mitochondrial DNA damage in human lymphocytes. Free Radic Biol Med 2006;40:1220–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gleyzer N, Vercauteren K, Scarpulla RC. Control of mitochondrial transcription specificity factors (TFB1M and TFB2M) by nuclear respiratory factors (NRF-1 and NRF-2) and PGC-1 family coactivators. Mol Cell Biol 2005;25:1354–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Virbasius JV, Scarpulla RC. Activation of the human mitochondrial transcription factor A gene by nuclear respiratory factors: a potential regulatory link between nuclear and mitochondrial gene expression in organelle biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:1309–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]