Abstract

Background

Abdominal aortic calcification (AAC) is a measure of subclinical cardiovascular disease (CVD). Data are limited regarding its relation to other measures of atherosclerosis.

Methods

Among 1,812 subjects (49% female, 21% black, 14% Chinese, and 25% Hispanic) within the population-based Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, we examined the cross-sectional relation of AAC with coronary artery calcium (CAC), ankle brachial index (ABI), and carotid intimal medial thickness (CIMT), as well as multiple measures of subclinical CVD.

Results

AAC prevalence ranged from 34% in those aged 45–54 to 94% in those aged 75–84 (p<0.0001), was highest in Caucasians (79%) and lowest in blacks (62%) (p<0.0001). CAC prevalence, mean maximum CIMT ≥ 1 mm, and ABI<0.9 was greater in those with vs. without AAC: CAC 60% vs 16%, CIMT 38% vs 7%, and ABI 5% vs 1% for women and CAC 80% vs 37%, CIMT 43% vs 16%, and ABI 4% vs 2% for men (p<0.01 for all except p<0.05 for ABI in men). The presence of multi-site atherosclerosis (≥ 3 of the above) ranged from 20% in women and 30% in men (p<0.001), was highest in Caucasians (28%) and lowest in Chinese (16%) and ranged from 5% in those aged 45–54 to 53% in those aged 75–84 (p<0.01 to p<0.001). Finally, increased AAC was associated with 2 to 3-fold relative risks for the presence of increased CIMT, low ABI, or CAC.

Conclusions

AAC is associated with an increased likelihood of other vascular atherosclerosis. Its additive prognostic value to these other measures is of further interest.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, calcification, cardiovascular disease, epidemiology

Persons with increased levels of coronary artery calcium (CAC), reduced ankle-brachial index (ABI), and increased carotid intimal medial thickness (CIMT) are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events and mortality1–7. CAC is associated with thoracic aortic calcium and aortic valve calcium,8–9 and significant associations have been also reported with descending aortic, abdominal aortic, iliac calcification10 and with CIMT, carotid plaques, and ABI11. Persons with diabetes who had coronary or aortic calcium also have a higher prevalence of peripheral, coronary, and overall CVD.12 There are limited data from large prospective studies examining the association of abdominal aortic calcium (AAC) with these more established measures of subclinical atherosclerosis, and in particular, a lack of ethnic-specific data on atherosclerosis in multiple sites. Understanding these relationships can help better establish the significance of AAC and overall atherosclerotic burden.

In the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), we examined the association of AAC with other measures of subclinical atherosclerosis, namely CAC, ABI, and CIMT, as well as the overall degree of “multi-site atherosclerosis” based on disease in multiple vascular beds.

Methods

Study Population

MESA is a prospective epidemiologic study of the prevalence, risk factors and progression of subclinical cardiovascular disease (CVD).13 Briefly, 6,814 participants aged 45–84 free of clinical CVD, identified as White, African-American, Hispanic, or Chinese, were recruited from six U.S. communities (Forsyth County, NC, Northern Manhattan and the Bronx, NY, Baltimore City and Baltimore County, MD, St. Paul, MN, Chicago, IL, and Los Angeles County, CA) in 2000–2002. Participants were solicited from lists of residents, dwellings, telephone exchanges, Medicare beneficiaries, and from referrals by other participants. Approximately equal numbers of men and women were recruited according to pre-specified age and race/ethnicity quotas. All participants gave informed consent.

An ancillary study of MESA measured AAC at the same examination that CAC was evaluated in a random sample of participants recruited between August 2002 and September 2005 from five MESA field centers: Northwestern University, Wake Forest University, UCLA, Columbia University, and the University of Minnesota. Of 2202 MESA participants recruited, 2172 agreed to participate, and 1990 satisfied eligibility criteria. Ten individuals had missing or incomplete scans for a total of 1980 participants with completed computed tomography scanning of their abdominal aorta.

Subclinical Vascular Disease Assessment

CAC was assessed by chest-CT using either a cardiac-gated EBCT scanner (Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York Field Centers) or a multi-detector CT system (Forsyth County and St. Paul Field Centers). Participants were scanned twice. A phantom of known physical calcium concentration was included in the field of view. The reader-work station interface identified and quantified CAC from images calibrated according to the readings of the calcium phantom, with the average Agatston score from the two scans used for analysis. Further details of the scanning methodology have been previously published.14

To measure AAC, a single CT scan was performed using a scan collimation of 3mm, slice thickness of 6mm, reconstruction using 6mm (5mm for sites with multidetector scanners) slices with 35 cm field of view, and normal kernel. All scan scores were brightness adjusted with a standard phantom. Scans were read centrally by the MESA CT Reading Center, and calcium in an 8 cm segment of the distal abdominal aorta above the aortic bifurcation was used for the purposes of the analysis in this manuscript. Calcification was identified as a plaque of ≥ 1mm2 with a density of >130 Hounsfield units and quantified using the Agatston scoring method.

CIMT was assessed by performing a B-mode ultrasonography of the right and left near and far walls of the internal carotid and common carotid arteries using a Logiq 700 ultrasound device (General Electric Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI) to record images. An ultrasound reading center (Department of Radiology, New England Medical Center) measured maximal IMT of the internal and common carotid sites as the mean of the maximum IMT of the near and far walls of the right and left sides.

ABI was calculated as the highest SBP value in the posterior tibial or dorsalis pedis taken from both legs divided by the highest SBP taken from both arms. Measurements were detected with a continuous wave Doppler ultrasound probe and taken after participant rested supine for 5 minutes.

We identified 1,812 participants (693 from MESA exam 2 and 1,119 from exam 3) with valid data for abdominal aortic calcification (AAC), coronary artery calcium (CAC) and risk factors. These data were merged with ABI data from exam 3 (ABI was not measured in exam 2) and internal carotid artery (ICA-CIMT) and common carotid intimal medial thickness (CCA-CIMT) data from exam 1 (the only exam when both CCA-CIMT and ICA-CIMT measures were performed).

Risk Factor Assessments

For each individual, resting blood pressure was measured three times in the seated position, and the average of the 2nd and 3rd readings was recorded. Smokers were ascertained by self report. Participants who reported smoking in the last 30 days were classified as current smokers. Total cholesterol, HDL, and triglyceride were determined using a Hitachi-911 instrument. LDL was estimated using the Friedewald equation. The laboratory belonged to the CDC/NHLBI standardization program.

Definitions

The presence of AAC was defined as an AAC Agatston score >0, the presence of CAC was defined as a CAC Agatston score >0, and an increased CIMT was defined as mean of the maximum internal and common CIMT ≥ 1mm based on this cut point being previously demonstrated to be associated with important increases in CHD risk.15 Since there are no prognostic data available for AAC, we have arbitrarily chosen AAC categories of 0, 1–99, 100–399, and ≥400, adapted from previously used categories for CAC and thoracic aortic calcium.16 A low ABI was defined as <0.9 based on levels below this cutpoint also being associated with increased CVD event risk17. Multi-site atherosclerosis was defined as having at least 3 or the following: CAC >0, AAC>0, averaged CIMT ≥1mm, and/or ABI <0.9.

Statistical Analysis

Initially, the prevalence of AAC by gender, race/ethnicity (Caucasian, Chinese, African American, and Hispanic), and age groups was compared by the Chi-square test of proportions. Similar analyses examined prevalence of CAC, mean CIMT ≥1 mm, and/or ABI < 1.0 by presence of AAC. Due to the skewed distribution of AAC, CAC, ICA-IMT, and CCA-IMT differences across ethnicity were examined using Kruskal-Wallis test. Spearman correlations were also calculated comparing AAC score with CAC score, CIMT, and ABI.

Relative risk regression18 (suitable when the disease/outcome is of high prevalence) was used to examine risk factors associated with each subclinical disease measure individually, as well as the likelihood of each subclinical CVD measure and multi-site atherosclerosis according to AAC assessed continuously (log transformed: ln(AAC+1)) or categorically. Similar analyses were done by AAC category examining the likelihood of having any one, two, or three of the other measures of subclinical CVD. Age, gender, and ethnicity-adjusted relative risks (and 95% confidence intervals) are presented.

SAS statistical software19 version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) was used for analysis. The alpha probability level for statistical analyses was set to 0.05.

Results

Age, gender, cardiovascular risk factors and measures of subclinical atherosclerosis are presented overall and by ethnicity in Table 1. Approximately 21% of subjects were black, 25% Hispanic, and 14% Chinese and 49% of the sample was female. All major risk factors and measures of subclinical disease differed significantly (p<0.001) across ethnicity. Blood pressure levels, current smoking, and HDL-cholesterol levels were highest in blacks. LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, and diabetes prevalence were highest in Hispanics. Mean levels of both AAC and CAC were highest in Caucasians and lowest in blacks and Chinese. CIMT levels were lowest in Chinese.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics: Risk Factors and Subclinical Disease Measures by Ethnicity

| Overall (N=1812) | White (N=734) (40.5%) | Chinese-American (N=247) (13.6%) | African-American (N=381) (21.0%) | Hispanic (N=450) (24.8%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (% Female) | 49.2 | 47.1 | 47.4 | 55.1 | 48.7 |

| Age, years*** | 64.5 (9.6) | 65.4 (9.5) | 64.6 (9.8) | 64.3 (9.5) | 63.1 (9.5) |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/dl*** | 111.4 (31.2) | 107.9 (29.0) | 109.6 (27.6) | 114.3 (33.8) | 115.8 (33.2) |

| Lipid-lowering medication (%)*** | 25.2 | 30.8 | 24.0 | 17.2 | 23.2 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/dl*** | 51.6 (15.2) | 52.4 (16.0) | 51.5 (14.0) | 54.6 (16.3) | 48.0 (12.6) |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl*** | 132.8 (95.6) | 132.4 (84.5) | 140.8 (86.6) | 105.3 (121.6) | 152.5 (86.7) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg*** | 123.7 (20.5) | 121.2 (19.3) | 121.2 (19.0) | 129.9 (21.7) | 123.8 (21.0) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg*** | 70.1 (9.8) | 68.9 (9.4) | 69.6 (9.7) | 72.8 (10.1) | 70.0 (10.0) |

| Taking hypertension meds (%)*** | 43.1 | 42.6 | 34.1 | 56.9 | 37.4 |

| Smoker, current (%)*** | 11.4 | 11.8 | 4.1 | 16.0 | 10.7 |

| Smoker, former (%)*** | 38.5 | 43.5 | 21.9 | 42.0 | 36.7 |

| Diabetes (%)*** | 13.6 | 8.7 | 13.4 | 16.8 | 18.9 |

| Family history of myocardial infarction or stroke (%)*** | 54.9 | 62.8 | 38.5 | 55.9 | 50.2 |

| Abdominal aortic calcium score*** | 1185.7 (2144.1) | 1629.3 (2592.3) | 882.9 (1690.7) | 752.6 (1518.0) | 994.9 (1867.5) |

| Coronary artery calcium score*** | 175.8 (432.3) | 225.7 (473.6) | 130.1 (41.5) | 129.4 (375.3) | 159.0 (415.4) |

| Internal carotid artery intimal-medial thickness (mm)*** | 1.1 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.6) | 0.84 (0.40) | 1.10 (0.66) | 1.03 (0.57) |

| Common cartotid artery intimal-medial thickness (mm)*** | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.87 (0.20) | 0.83 (0.17) | 0.90 (0.20) | 0.86 (0.19) |

| Ankle brachial index | 1.1*** (0.1) | 1.14 (0.12) | 1.12 (0.12) | 1.10 (0.15) | 1.14 (0.12) |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001 across ethnicity; sample sizes vary slightly for some of the risk factors. Comparisons for CAC and AAC were based on the Kruskal-Wallis test for comparing rank sums.

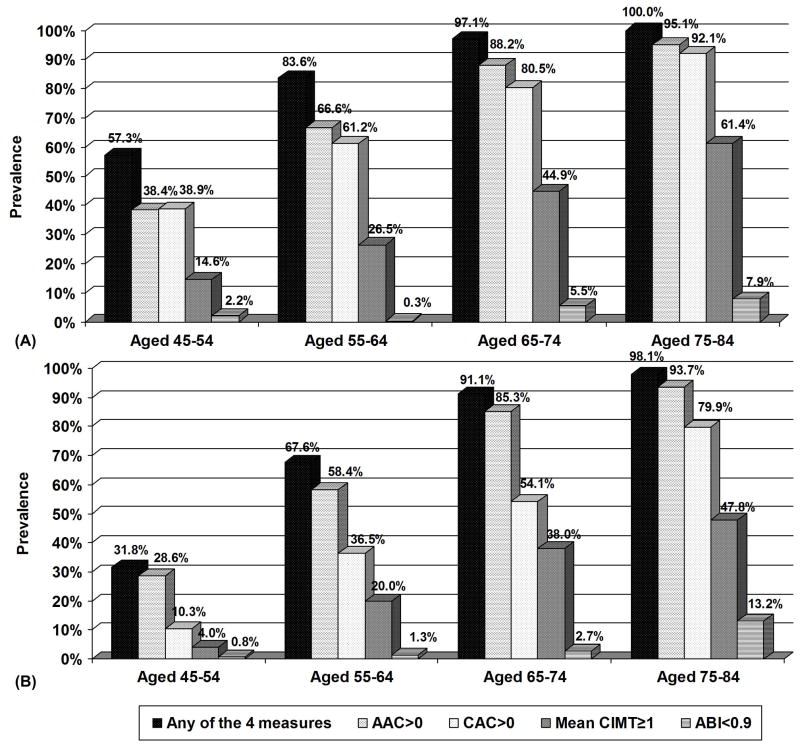

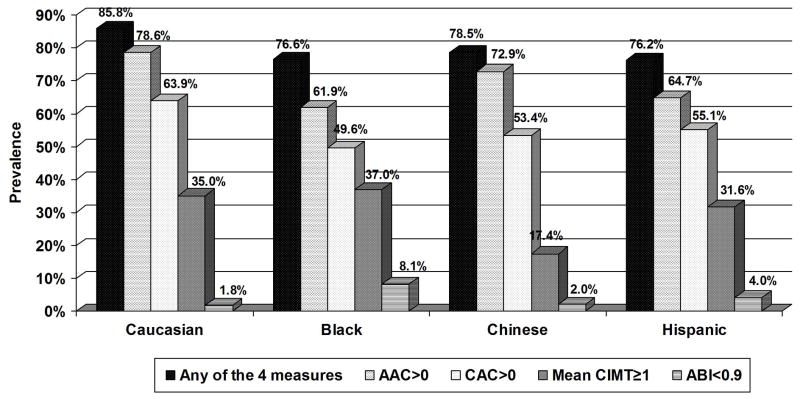

The prevalence of AAC>0, CAC>0, mean CIMT≥1, and ABI<0.9 increased across age groups in both men and women (Figure 1). 57% of men aged 45–54 to 100% of men aged 75–84 years had at least one of the four measures positive; for women these prevalences ranged from 32% to 98%, respectively. Caucasians had the highest prevalence of AAC and CAC. African-Americans had the highest prevalence of CIMT≥1 and ABI<0.9. Chinese, however, had the lowest prevalence of increased CIMT (p<0.01 across ethnicity) (Figure 2). Moreover, 86% of Caucasians, 77% of blacks, 79% of Chinese and 77% of Hispanics had at least one of the four measures positive. Overall Spearman correlations of AAC with other subclinical disease measures included 0.455 for CIMT, −0.181 for ABI, and 0.573 for CAC (all p<0.0001) and were similar by ethnicity (0.479, −0.203, and 0.579, respectively for Caucasians, 0.458, −0.115, and 0.594, respectively for Chinese, 0.465, −0.306, and 0.471, respectively for blacks, and 0.428, 0.150, and 0.571, respectively for Hispanics).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of AAC>0, CAC>0, mean maximum CIMT≥1mm, ABI<0.9, and any of the four measures by age in men (A) and women (B). p<0.001 for each measure across age categories in both men and women.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of AAC>0, CAC>0, mean maximum CIMT≥1mm, ABI<0.9, and any of the four measures by ethnicity. p<0.01 for each measure across ethnicity.

Among risk factors associated with AAC>0, CAC>0, CIMT>=1mm, and ABI<0.9 from multivariable relative risk regression (Table 2), age was most consistently related to all measures, but male gender was associated with a greater likelihood of CAC and increased CIMT only. Blacks and Hispanics were substantially more likely to have low ABI. Increased LDL-C and low HDL-C were associated with only AAC and low ABI. Current smoking related to an increased likelihood of AAC, increased CIMT, and low ABI, while former smoking was related to all measures except low ABI. Increased BMI was positively associated with CAC and CIMT, but negatively associated with ABI. Increased systolic blood pressure was most strongly related to increased CIMT and low ABI, while low diastolic blood pressure was associated only with increased CIMT. A family history of CHD was most strongly related to CAC while diabetes was strongly associated with both AAC and CAC.

Table 2.

Multivariable relative risk regression of risk factors for AAC>0, CAC>0, CIMT>1mm, and ABI<0.9 )

| AAC>0 (n=1774) | CAC>0 (n=1774) | CIMT>1 mm (n=1770) | ABI<0.9 (n=1774) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (per SD) | 1.27*** | 1.34*** | 1.43*** | 2.26*** |

| Gender (female vs. male) | 0.98 | 1.37*** | 1.49*** | 1.02 |

| African-American vs. Caucasian | 0.82*** | 0.82*** | 1.08 | 18.48*** |

| Chinese vs. Caucasian | 1.03 | 0.96 | 0.65** | 5.62* |

| Hispanic vs. Caucasian | 0.86*** | 0.95 | 0.95 | 10.92*** |

| LDL-cholesterol (per SD) | 1.05*** | 1.01 | 1.04 | 1.47** |

| HDL-cholesterol (per SD) | 0.95*** | 0.98 | 1.05 | 0.37*** |

| Triglycerides (per SD) | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.08 | 0.60 |

| Smoking, Current vs. Never | 1.36*** | 1.06 | 1.29* | 2.52** |

| Smoking, Former vs. Never | 1.19*** | 1.13*** | 1.29*** | 0.72 |

| Body mass index (per SD) | 1.02 | 1.07*** | 1.14*** | 0.61** |

| Systolic BP (per SD) | 1.04* | 1.02 | 1.24*** | 1.58*** |

| Diastolic BP (per SD) | 1.00 | 1.03 | 0.83*** | 0.83 |

| Family history CHD (yes vs. no) | 1.06* | 1.17*** | 1.14* | 0.79 |

| Diabetes (yes vs. no) | 1.11*** | 1.13** | 1.16* | 1.06 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

The prevalences of CAC > 0, mean CIMT ≥ 1mm, and ABI <0.9 were higher among those with versus without AAC (p<0.01) (Figure 3A, Supplementary Material). Among those with AAC, approximately 40% of women and 20% of men did not demonstrate evidence of CAC and 71% of women (84% of men) had at least one of the other 3 measures of atherosclerosis; however 21% of women (47% of men) among those without AAC had at least one of these 3 measures (p<0.0001 comparing men and women) showing that the absence of AAC does not exclude the likelihood of atherosclerosis in other vascular beds.

In all ethnic groups the prevalence of CAC > 0 and mean maximal CIMT ≥ 1mm were significantly higher among those with versus those without AAC (p<0.01). While the presence of AAC was associated with subclinical CVD in one or more of the other 3 locations 68–80% of the time depending on the ethnic group, among those without AAC, subclinical CVD in one or more of the other 3 locations was still present in 39% of Blacks, 34% of Caucasians, 33% of Hispanics and 21% of Chinese (Figure 3B, Supplementary Material).

For each log unit increment in AAC, the likelihood of CIMT ≥1 mm, ABI<0.9, and for CAC>0 and CAC≥400 increased. Higher categories of AAC were also associated with an increased likelihood of CAC and CIMT≥1mm (Table 3). Higher levels of AAC were also associated with an approximate 2-fold greater likelihood of having any measure (one or more of increased CIMT, low ABI, or positive CAC). Upon full multivariable adjustment (not shown), the RR’s remained essentially the same with a similar level of statistical significance. Similar analyses (data not shown) also showed higher AAC scores to be associated with higher RR’s for any 2 measures (RR’s range from 2.4 to 6.3, p<0.001) and for all 3 measures of subclinical CVD (RR 11.0, p<0.01 for those with AAC ≥400 vs. 0).

Table 3.

Multivariable relative risk (RR) estimates of elevated IMT, ABI<0.9, CAC>0, and CAC≥400 by continuous and categorical AAC (MESA Study)

| RR (95% CI) Likelihood of elevated IMT≥1 mm1 | RR (95% CI) Likelihood of ABI <0.9 | RR (95% CI) Likelihood of CAC >0 | RR (95% CI) Likelihood of CAC≥400 | RR (95% CI) Likelihood of any Measure of Subclinical CVD3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAC Continuous2 (n=1,812) | 1.19*** (1.15–1.22) | 1.30** (1.08–1.56) | 1.12*** (1.10–1.14) | 1.68*** (1.52–1.87) | 1.10*** (1.08–1.11) |

| AAC = 02 (n=528) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| AAC 1–99 (n=256) | 1.55* (1.11–2.18) | 0.38 (0.07–1.95) | 1.54*** (1.28–1.86) | 1.63 (0.61–4.34) | 1.48*** (1.26–1.72) |

| AAC 100–399 (n=253) | 1.99*** (1.47–2.70) | 1.25 (0.44–3.60) | 1.87*** (1.58–2.21) | 3.22** (1.36–7.61) | 1.76 *** (1.54–2.02) |

| AAC > 400 (n=775) | 3.06*** (2.36–3.98) | 1.53 (0.57–4.08) | 2.37*** (2.04–2.75) | 6.81*** (3.15–14.76) | 2.07*** (1.84 –2.35) |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001;

Defined as the averaged maximum ICA-IMT and CCA-IMT >1.0 mm;

Adjusted for age, gender, and ethnicity; ACC continuous is defined as ln(AAC + 1);

Defined as elevated IMT, ABI<0.9, and/or CAC >0. ACC continuous is defined as ln(AAC + 1); p<0.0001 for test of trend across AAC categories.

In addition, the prevalence rates of multi-site atherosclerosis (at least 3 of the following: AAC>0, CAC>0, mean CIMT≥1 mm, and ABI<0.9) ranged from 20% in women and 30% in men (p<0.001), was highest in Caucasians (28%), Hispanics (25%) and African-Americans (24%) and lowest in Chinese-Americans (16%) (p<0.001 across ethnicity) and ranged from 5% in those aged 45–54 to 53% in those aged 75–84 (p<0.01 to p<0.001).

Discussion

AAC is strongly associated with subclinical CVD in other vascular beds, including the coronary, carotid, and leg arteries. While less than 20% of persons under age 65 have evidence of subclinical atherosclerosis in ≥3 vascular beds, this increases to more than 50% after age 75. While the presence of AAC was closely associated with the presence of subclinical CVD elsewhere, even in the absence of AAC, subclinical CVD elsewhere was present in over one-fourth of women and nearly half of men. Importantly, among persons with AAC, approximately 40% of women and 20% of men did not demonstrate CAC, and in those without CAC, nearly 60% of women and over 50% of men had evidence of subclinical CVD elsewhere (with most of this including AAC), an important finding considering the popularity of screening for CAC as a measure of atherosclerosis.

The concordance of atherosclerosis in multiple vascular beds is not a new finding and extends throughout the lifespan. Decades ago, the International Atherosclerosis Project examined the concurrence of atherosclerosis in the cerebral and coronary arteries and the aorta from autopsy studies, finding a general association between the extent of raised lesions in one arterial bed with that of another; however, little association between atherosclerosis in the carotid arteries was found with that of the coronaries or the aorta.209 In the Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) study21, evidence of atherosclerotic lesions were seen in all of the aortas and about half of the right coronaries among youth aged 15–19 years, with the extent of intimal surface involved increasing with age. Allison and colleagues10 showed in a screened cohort of 650 asymptomatic subjects strong correlations of proximal and distal aortic calcium with calcium in the coronaries, and especially in the iliac arteries and that both the prevalence of proximal and distal aortic calcium was less than that of CAC until the 7th decade of life. More recently, in the MESA study, Takasu and colleagues22 demonstrated a strong association of descending thoracic aortic calcification (DTAC) (also measured by computed tomography) with CAC. Overall, while 44% had neither CAC nor DTAC, 28% had only CAC, only 6% had exclusively DTAC, and 22% had both CAC and DTAC. Moreover, in Chinese adults, AAC assessed by electron beam CT was independently associated with CAC.23 Among elderly participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study, Kuller et al. 24 showed 61% of subjects to have some measure of subclinical CVD (based on a composite of electrocardiographic abnormalities, ABI<0.9, increased CIMT, echocardiographic abnormalities, angina, or claudication), and such persons to be at increased risk of future CHD events.

Among 2,056 women aged 65 years and over, AAC measured by chest radiographs predicted all-cause mortality and non-CVD, with trend for CVD and CHD mortality over up to 13 years of follow-up. 25 Other smaller studies have confirmed the prognostic significance of aortic calcium (from the entire abdominal aorta) as detected by lateral spine images from bone densitometry in older women26, and in hemodialysis subjects with documented AAC from lateral abdominal roentgenographs.27 Moreover, we have recently demonstrated among 2,303 asymptomatic adults a modest relation of thoracic aortic calcium with CVD events, although there was no incremental predictive value over that provided by CAC.16

The multiethnic composition and strict standardization and quality control for assessment of AAC and the other subclinical CVD measures are strengths of our study. A limitation is that not all measures were obtained at the same time; some measures were obtained within a few years of each other. The cross-sectional nature of our study therefore precludes making any inferences regarding whether certain subclinical disease measures preceded others. Importantly, this manuscript does not address whether AAC provides prognostic information for CVD outcomes beyond that offered by CAC, which requires less radiation; this will be an important question for future research. It was also beyond the scope of this paper to examine relationships of AAC with thoracic aortic calcification, aortic dilatation, or aortic aneurysms. It is also possible that findings from earlier measures of CAC and ABI in Exam 1 may have influenced therapy, possibly affecting future measures; however, there is no evidence of such therapeutic effects in MESA, nor in clinical trials. Finally, our cutpoints for defining CAC, AAC, low ABI, or increased CIMT, while based on known scoring systems or associations with risk, are somewhat arbitrary, and use of different cutpoints would have altered relationships noted. For example, the 1mm cutpoint for CIMT has normally been used to refer to a mean of the mean internal and common IMT; however, in MESA it is being applied to the mean of the maximum IMT and thus the 1mm cutpoint in our study is reflective of less atherosclerosis.

In conclusion, we note a strong association of AAC measured by CT with other subclinical disease measures in a multiethnic cohort of U.S. adults. While the presence of AAC is closely associated with the presence of subclinical CVD elsewhere (particularly CAC), even in the absence of AAC, subclinical CVD elsewhere is not uncommon. However, before AAC can be considered as a potential target for screening, further follow-up of the MESA cohort will be essential to determine the prognostic significance of AAC, including whether it provides additional predictive value for CVD events over other measures such as CAC and CIMT.

Supplementary Material

Prevalence of CAC>0, mean maximum CIMT≥1mm, ABI<0.9, and any of the 3 by presence of AAC, by gender (A) and ethnicity (B). All gender comparisons p<0.01 when compared to no AAC. For ethnicity, all comparisons p<0.01 when compared to no AAC, except prevalence of ABI<0.9 for Caucasians (p<0.05), Chinese (p=0.20), and Hispanics (p<0.05).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by contracts N01-HC-95159 through N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95169, and R01 HL-65580 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The authors thank the other investigators, staff, and participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions, November 2006.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wong ND, Hsu JC, Detrano RC, Diamond G, Eisenberg H, Gardin JM. Coronary artery calcium evaluation by electron beam computed tomography: relation to new cardiovascular events. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:495–98. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01000-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arad Y, Spadaro LA, Goodman K, Newstein D, Guerci AD. Prediction of coronary events with electron beam computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1253–60. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00872-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Detrano RC, Wong ND, Doherty TM, Shavelle RM, Tang W, Doherty TM, Ginzton LE, Budoff MJ, Narahara KA. Coronary calcium does not accurately predict near-term future coronary events in high-risk adults. Circulation. 1999;99:2633–2638. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.20.2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kondos GT, Hoff JA, Sevrukov A, Daviglus ML, Garside DB, Devries SS, Chomka EV, Liu K. Electron-beam tomography coronary artery calcium and cardiac events: a 37-month follow-up of 5,635 initially asymptomatic low to intermediate-risk adults. Circulation. 2003;107:2571–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000068341.61180.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw LJ, Raggi P, Schisterman E, Berman DS, Callister TQ. Prognostic value of cardiac risk factors and coronary artery calcium for all-cause mortality. Radiology. 2003;228:826–33. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2283021006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, et al. for the Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:14–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Criqui MH, Langer RD, Fronek A, et al. Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:381–386. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202063260605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong ND, Sciammarella M, Miranda-Peats R, Whitcomb B, Gallagher A, Gransar H, Friedman J, Hayes S, Berman DS. Relation of Thoracic Aortic and Aortic Valve Calcium to Coronary Artery Calcium and Risk Assessment. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:951–55. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00976-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adler Y, Fisman EZ, Shemesh J, Schwammenthal E, Tanne D, Batavraham IR, Motro M, Tenenbaum A. Spiral computed tomography evidence of close correlation between coronary and thoracic aorta calcifications. Atherosclerosis. 2004;176:133–8. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allison MA, Criqui MH, Wright CM. Patterns and risk factors for systemic calcified atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:331–336. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000110786.02097.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oei HH, Vliegenthart R, Hak AE, Iglesias de Sol A, Hofman A, Oudkerk M, Witteman JC. The association between coronary calcification assessed by electron beam computed tomography and measures of extracoronary atherosclerosis: the Rotterdam Coronary Calcification Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1745–51. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reaven PD, Sacks J. Investigators for the VADT. Coronary artery and abdominal aortic calcification are associated with cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1640-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacobs DR, Kronmal R, Liu K, Clark Nelson J, O’Leary D, Saad MF, Shea S, Szklo M, Tracy RP. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;156:871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carr JJ, Nelson JC, Wong ND, McNitt-Gray M, Arad Y, Jacobs DR, Jr, Sidney S, Bild DE, Williams OD, Detrano R. Calcified Coronary Artery Plaque Measurement with Cardiac CT in Population-based Studies: Standardized Protocol of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Radiology. 2005;234:35–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chambless LE, Heiss G, Folsom AR, Rosamond W, Szklo M, Sharrett AR, Clegg LX. Association of coronary heart disease incidence with carotid arterial wall thickness and major risk factors: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, 1987–1993. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:483–94. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong ND, Gransar H, Shaw L, Polk D, Moon JH, Miranda-Peats R, Hayes SW, Thomson LEJ, Rozanski A, Friedman JD, Berman DS. Thoracic aortic calcium versus coronary artery calcium for the prediction of coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease events. J Am Coll Cardiol Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:319–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ankle Brachial Index Collaboration. Ankle brachial index combined with Framingham Risk Score to predict cardiovascular events and mortality. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:197–208. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lumley T, Kronmal RA, Ma S. UW Biostatistics Working Paper Series. University of Washington; 2006. Relative risk regression in medical research: models, contrasts, estimators and algorithms. paper 293, http://www.bepress.com/uwbiostat/paper293. [Google Scholar]

- 19.SAS Procedures Guide, version 6.12. 3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solberg LA, McGarry PA, Moossy J, Strong JP, Tejada C, Loken AC. Severity of atherosclerosis in cerebral arteries, coronary arteries, and aortas. Ann New York Acad Sci. 1968;149:956–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb53849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) Research Group. Natural history of aortic and coronary atherosclerotic lesions in youth. Findings from the PDAY Study. Arterioscler Thromb. 1993;13:1291–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.13.9.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takasu J, Budoff MJ, O’Brien KD, Shavelle DM, Probstfield JL, Carr JJ, Katz R. Relationship between coronary artery and descending thoracic aortic calcification as detected by computed tomography: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204:440–6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu MH, Chern MS, Chen LC, Lin YP, Sheu MH, Liu JC, Changh CY. Electron beam computed tomography evidence of aortic calcification as an independent determinant of coronary artery calcification. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69:409–14. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuller LH, Arnold AM, Psaty BM, Robbins JA, O’Leary DH, Tracy RP, Burke GL, Manolio TA, Chaves PHM. 10-year follow-up of subclinical cardiovascular disease and risk of coronary heart disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:71–78. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodondi N, Taylor BC, Bauer DC, Lui LY, Vogt MT, Fink HA, Browner WS, Cummings SR, Ensrud KE. Association between aortic calcification and total and cardiovascular mortality in older women. J Intern Med. 2007;261:238–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schousboe JT, Taylor BC, Kiel DP, Ensrud KE, Wilson KE, McCloskey EV. Abdominal aortic calcification detected on lateral spine images from a bone densitometer predicts incident myocardial infarction or stroke in older women. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:409–16. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.071024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okuno S, Ishimura E, Kitatani K, Fujino Y, Kohno K, Maeno Y, Maekawa K, Yamakawa T, Imanishi Y, Inaba M, Nishizawa Y. Presence of abdominal aortic calcification is significantly associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:417–25. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Prevalence of CAC>0, mean maximum CIMT≥1mm, ABI<0.9, and any of the 3 by presence of AAC, by gender (A) and ethnicity (B). All gender comparisons p<0.01 when compared to no AAC. For ethnicity, all comparisons p<0.01 when compared to no AAC, except prevalence of ABI<0.9 for Caucasians (p<0.05), Chinese (p=0.20), and Hispanics (p<0.05).