Abstract

Chemotaxis plays a critical role in tissue development and wound repair, and is widely studied using ex vivo model systems in applications such as immunotherapy. However, typical chemotactic models employ 2D systems that are less physiologically relevant or use end-point assays, that reveal little about the stepwise dynamics of the migration process. To overcome these limitations, we developed a new model system using microfabrication techniques, sustained drug delivery approaches, and theoretical modeling of chemotactic agent diffusion. This model system allows us to study the effects of 3D architecture and chemotactic agent gradient on immune cell migration in real time. We find that dendritic cell migration is characterized by a strong interplay between matrix architecture and chemotactic gradients, and migration is also influenced dramatically by the cell activation state. Our results indicate that Lipopolysaccharide-activated dendritic cells studied in a traditional transwell system actually exhibit anomalous migration behavior. Such a 3D ex vivo system lends itself for analyzing cell migratory behavior in response to single or multiple competitive cues and could prove useful in vaccine development.

Introduction

Concentration gradients of bioactive signaling molecules regulate processes ranging from embryonic development[1] to wound repair,[2] as cells express directional locomotion directed by these gradients in a process termed chemotaxis. Commonly used chemotactic assays include Boyden chamber,[3] under-agarose assay,[4] Zigmond chamber,[5, 6] Dunn chamber,[7] and micropipette assay [8]. These assays, although inexpensive and easy to use, have several limitations; they restrict observation of cell migration to two dimensions, do not allow one to monitor the dynamics of migration and do not sustain the signaling gradients for more than a few hours.[9] For example, the Boyden chamber, which is an endpoint assay, does not allow observation of chemotaxis visually, and cannot directly distinguish chemotaxis (oriented locomotion) from chemokinesis (stimulated nondirected or random locomotion). Various confounding variables, including variations in the pore size and thickness of membranes used in this assay further obscure the migratory response of cells to chemokines.[10, 11] Variations to existing systems allow for the development of gradients with better stability[12, 13]. Microfluidics-based methods for generating stable concentration gradients have recently been developed,[14, 15] but they typically expose cells to shear flow, which can bias directional motility[16] and inadvertently dilute autocrine/paracrine factors secreted by the cells. Current microfluidic chemotaxis chambers also limit studies of cell migration to two-dimensional (2D) substrates, but many relevant biological processes including immune cell migration and cancer cell invasion, involve migration in a three-dimensional (3D) environment.

A particularly important example of 3D cell migration is the chemotaxis of dendritic cells (DCs). DCs act as sentinels for the immune system, with immature dendritic cells patrolling the body to seek out foreign agents such as bacteria, viruses, or toxins. The dendritic cells bind, ingest, and present fragments of antigens on cell surface receptors; in addition, encounters with antigens also trigger dendritic cell maturation (or activation), which enables these cells to home to the lymph nodes in response to chemotactic agents (chemokines) secreted from the node.[17] The upregulation of chemokine receptors upon the activation of DCs allows chemotactic migration of these cells.[18] Specifically, mature dendritic cells upregulate CCR7, a chemotactic factor receptor that binds the lymph node-derived chemokines CCL19 and CCL21.[18, 19] Expression of CCR7 enables the directed migration of these cells to the spleen, or through the lymphatic system to a lymph node, where they present antigens to other immune cells, and generate an immune response to the antigen.[20, 21] Maturation also involves upregulation of other cell-surface receptors including CD80 (B7.1), CD86 (B7.2), and CD40, that act as co-receptors and enhance T-cell activation.[17] In spite of the importance of dendritic cell migration to proper immune system function and successful DC-based anti-tumor therapy, quantitative understanding of 3D dendritic cell migration is currently quite limited.

In this paper, we describe an approach to simultaneously study the influence of chemotactic signals and 3D architectural features of an adhesion substrate on directed 3D dendritic cell migration. We used two-photon polymerization to fabricate 3D interconnected scaffolds with precise architectural control at the micrometer scale. A sustained release system is integrated into a microfabricated chamber to generate chemotactic gradients in the scaffolds containing cells. We developed a theoretical model to obtain the concentration, release and gradient profiles of chemokines and to predict a range of scaffold architectural parameters that either promote or restrain the motion of cells in response to a chemokine gradient. Finally, a live imaging and analysis system permits us to study chemotactic cell migration within the scaffolds, and to directly test how architectural features regulated chemokine-driven chemotaxis.

Materials and Methods

Primary cells (DCs) isolation and culture

A protocol developed by Lutz, et al.[22] was adopted for generation and purification of primary bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs). Briefly, bone marrow cells were flushed from the femurs of green fluorescent protein-expressing (GFP) C57BL/6 mice and cultured in 100-mm bacteriological petri dishes (Falcon number 1029/Becton Dickinson). Cell culture medium RPMI-1640 (R10) (Sigma) was supplemented with 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Invitrogen), 2 mM L-Glutamine (Invitrogen), 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma) and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen). At day 0, bone marrow leukocytes were seeded at 2 × 106 cells per 100-mm dish in 10 ml R10 medium containing 20 ng/ml granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GMCSF) (Peprotech). At day 3 another 10 ml R10 medium containing 20 ng/mL GMCSF was added to the plates. At days 6 and 8, half of the culture supernatant was collected and centrifuged, the cell pellet was resuspended in 10 ml fresh R10 containing 20 ng/mL GMCSF, and placed back into the original plate. We used the non-adherent cell population in the culture supernatant between days 8 and 12 for all our experiments.

Transwell migration

Transwell migration studies were performed by plating cells in the top well, and adding chemokine/adjuvant to the bottom well underneath the porous membrane. 600 μL of media with 300 ng/mL of CCL19 (Peprotech) was added to the bottom wells. 3 × 105 cells suspended in 100 μL of conditioned media were added to the top transwell. Three cell conditions were tested: (1) unstimulated cells, (2) cells stimulated with condensed 5 g/mL CpG (Invivogen) (with 1 g/mL prostaglandin E2 (PGE2, from Cayman Chemical) and (3) cells stimulated with 1 g/mL LPS (Sigma). The number of cells that migrated from the top well to the bottom well through the porous membrane was counted at the end of 12 h to quantify migration. Cells that had migrated to the bottom well were collected by treatment with 0.25% trypsin-0.03% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, Invitrogen) and counted with a Z2 coulter counter (Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

FACS staining and sorting

CpG was condensed with polyethyleneimine (PEI, Sigma)[23] to decrease its size and enhance its uptake by cells. As PGE2 has been reported to enhance dendritic cell activation and migration in vitro[24, 25] it was used in conjunction with CpG activation. For activation, 5 μg/mL of condensed CpG and 1 μg/mL of PGE2 were used, or 1 μg/mL of LPS.

For fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) characterization, cells were stimulated with CpG/PGE2 or LPS for 24 h, and then collected (3 × 106 cells for each condition) to stain and quantify for surface presence of the costimulatory molecule CD86. For staining, the cells were washed and resuspended in a wash medium‘ consisting of phosphate buffered saline solution with 10% FBS (Invitrogen) and 1% sodium azide (Sigma). Using 0.06 μg of antibody per million cells in a 100-μL volume of wash medium, cells were incubated with a fluorophore tagged anti-CD86 molecule (Ebioscience) for 30 min over ice on a shaker. The cells were washed thrice in wash medium and FACS analysis was used to quantify the number of fluorescently labeled cells for different stimulatory conditions. The percentage activation was measured against the isotype control, to account for non-specific staining.

To separate the 100% activated cell population from their unactivated counterparts, the cells were preactivated with CpG for 24 h. They were then stained with CD86 antibody as described above and sorted using FACS machine to collect both positive and negative populations.

Fabrication of L-shaped device

An L-shaped device for studying chemotaxis was made using a combination of two-photon polymerization and polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) molding. First, two-photon polymerization was used to fabricate a scaffold using triacrylate polymer on a coverglass as described in detail in our previous work.[26] Briefly, the triacrylate monomer was placed on a coverglass and polymerized using a focused femtosecond laser beam. The unpolymerized monomer was washed off using a solvent to yield a three-dimensional interconnected scaffold. The scaffolds were 600 μm long, 600 μm wide and about 100 μm high. Then PDMS walls 1 mm in height by 1 mm in width, as shown in Figure 1, were replicated from an L-shaped mold made from plastic. The center of middle chamber of the L-shaped device was aligned with the center of the scaffold under a microscope and the walls were stuck to the cover glass with the scaffolds. Each chamber in the L-shaped device was 3 mm × 3 mm.

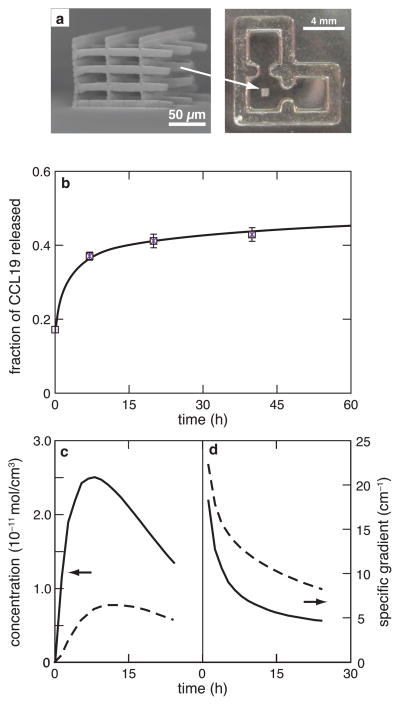

Figure 1.

Development of migration system. (a) Left: Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of two-photon polymerized scaffold showing its interconnected and porous three-dimensional structure; right: brightfield image of a PDMS-molded, L-shaped device with a two-photon polymerized scaffold in the center; (b) amount of chemokine released from collagen gels, measured as a fraction of total chemokine incorporated; time dependence of the (c) concentration and (d) specific gradient of the chemokine in the center of the scaffold (solid line) and at the left edge of the device (dashed line), as predicted by finite element modeling.

Chemokine release study

To measure the release profile of chemokine, a collagen solution containing the chemokine was prepared. Collagen gel discs were prepared by placing 50-μL drops of each of this solution in a 24-well plate and allowing them to gel for 1 h. The discs were placed in blank media and the surrounding medium was collected and replenished at regular time intervals. Cumulative release of the chemokine in the surrounding medium was measured using an Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit for analyzing and measuring CCL19.

Collagen gel preparation, cell seeding and device set-up

Rat tail collagen I (BD Biosciences) was used for all the experiments with collagen and is referred to as the stock solution, which has a starting concentration of 3.5 mg/mL. A neutralized working solution of collagen was prepared by mixing the collagen stock solution with 10× RPMI medium in a 9:1 ratio and adding 23 μL of 1M NaOH (sodium hydroxide) for every mL of collagen stock solution. The pH of the working solution was adjusted to 7–7.4 using 1M NaOH or 1M HCL solutions. Finally, a 1.2-mg/mL solution of collagen was prepared by mixing the required amount of 1× RPMI medium to the neutralized working solution of collagen. This solution would gel if kept under physiological conditions of 37 C, 5% CO2, and humidified atmosphere for 1 h.

Green fluorescent protein-expressing dendritic cells isolated from GFP mice and cultured as described above, were encapsulated in collagen gel by making a low density (106 cells/mL) suspension of cells in collagen solution. 17.5 μL of the cell-collagen suspension was added to the center chamber of the —L-shaped chamber and the device was kept inside an incubator maintained at 37° C and 5% CO2 for 10 min. Then 15 μL of 1.2-mg/mL solution of collagen (blank or with chemokine) was added to the side chambers, as required and kept in the incubator for 30 min. After that, 600 μL of blank collagen solution was added on the top and again kept in the incubator for 1 h. Finally, RPMI medium without GMCSF was added to prevent the collagen gel from drying. For all experiments, the chemokine source (collagen gel with chemokine) was placed in the right chamber, so that the cells would experience a pull in the positive x-direction in the presence of a chemokine. Soon after the cells were seeded into the chamber, live imaging was started. Z-stacks of fluorescence images were taken at the center of the chamber.

Live imaging, cell tracking and analysis

Snapshots were taken at the center of chamber, where the scaffold is present and also outside the scaffold (on the right side) to compare the motion of cells within and outside of scaffold. Images were taken at intervals of 4 min for a period of 24 h. Imaris software was then used to analyze the images and track the motion of cells. To take into account the movement of cells with respect to the chemokine chamber, average x-velocity was defined and calculated as the total displacement in the x-direction divided by the total imaging time for each cell, and averaging this value for all the cells in a given condition. If the chemokine is placed on the right side of the cells then a positive average x-velocity corresponds to a directed motion towards the chemokine. Average y- and average z-velocities were calculated in a similar manner. The overall average speed of the cells was also calculated, and defined as the total distance travelled by each cell divided by total imaging time.

Modeling

The concentration of a chemokine inside any part of the device was calculated from Fick‘s law of diffusion given by:

| (1) |

Here, c is the concentration of the chemokine varying in time and space, D is the diffusion coefficient of the chemokine in gel and R is the reaction rate of the chemokine. The diffusion coefficient in gel and water were assumed to be similar and the value used for calculation was 1.4 × 10 6 cm2/sec. The degradation of the chemoattractant was assumed to follow a first-order reaction. ELISA was used to measure its bioactivity and calculate the half-life, which was found to be 12 h (data not shown). This led to a reaction rate of −0.000016c. COMSOL finite element modeling software was used for simulations.

A one dimensional model was used to describe the cell concentration u in time t and space by [31]:

| (2) |

Here, c is the concentration of the chemokine varying in time and space, χ is a chemotactic coefficient and μ is the random motility (i.e., cell diffusion) coefficient. μ and χ are taken to be constant about the values of c and δc/δx that are considered. The concentration of the chemokine c follows the diffusion law given by Eq. 1. A continuum model was used so that the effect of architecture could be incorporated as well (Figure 6). Using the necessary initial and boundary conditions inside the specified architecture of the system, Eqs. 1 and 2 were solved, accounting for the dynamic interplay of cell and chemokine concentrations.

Figure 6.

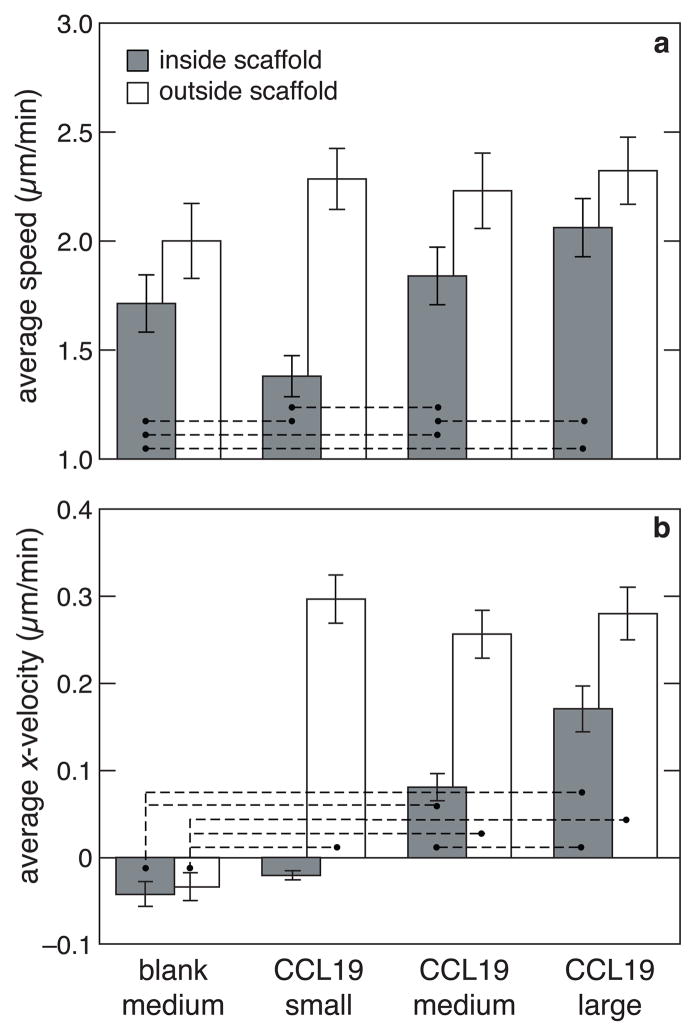

Combined effect of chemotactic signaling and architecture on the speed and velocity of dendritic cells. (a) average speed of cells inside small, medium and large scaffolds in the presence of CCL19 compared to a control of cells in a medium scaffold in the absence of CCL19 (blank medium). Gray bars indicate the speeds within the scaffold while white bars indicate the speed of cells outside the scaffold. Statistical significance was evaluated for difference in values between the control (blank medium) and the remaining three conditions and also for difference between various pairs. For pairs connected by a dashed line p < 0.05. (b) Average x-velocity of cells inside and outside the scaffolds for all the above conditions. For each condition, statistical significance was evaluated for non-zero x-velocity values. Statistical significance was also evaluated for difference in values between other pairs. For pairs connected by a dashed line p < than 0.05.

The initial conditions were set to take into account the presence of a source of chemokine on the right side and the presence of cells in the center chamber. The boundary conditions were set for the flux of the cells (ngD∇u = 0) and that of the chemokine (ngD∇c = 0) to be zero inside the solid beams of the scaffold. Also, the concentration of both the cells (u = 0) and the chemokine (c = 0) were set to zero. For all the simulation work, parameters were derived from the experimental values.

Results

Development of migration system

As described previously,[26] two-photon polymerization was used to fabricate scaffolds for studying the migration of cells in three dimensions. The photopolymerized scaffolds were fabricated in the shape of interconnected woodpile structures, that were approximately 600 μm long and wide, and 100 μm high (Fig. 1a). The pore sizes used for this study were 25 μm, 50 μm and 75 μm; the corresponding scaffolds are designated as small, medium and large, respectively. All chemotaxis related experiments in this study were carried out with CCL19 as the chemokine. In order to monitor the real-time CCL19 effects on directed migration of cells, a device was fabricated to generate chemotactic gradients. This device was modeled in an L-shape, with the CCL19 localized in collagen gel in one of the end-chambers (Fig. 1a). This chamber served as chemokine source for cells localized in the middle chamber. Finite element modeling was used to determine the required dimensions and the role of CCL19 release kinetics in generating gradients in the device. The time evolution of concentration of CCL19 in the cell chamber was calculated from Fick‘s law of diffusion. CCL19 was mixed directly into a gel and placed in one of the end-chambers. Direct measurement of chemokine release from the gel revealed that most of the chemokine is released during the first 24 h (Fig. 1b). The concentration (c) profile of CCL19 in the cell chamber showed an initial increase, followed by a gradual decrease (Fig. 1c) due to depletion of CCL19 from the gel and its limited half-life after release.[27] While the concentration and the concentration gradient (δc/δx ) exhibited similar profiles, the specific gradient ((1/δc) δc/δx), which represents the fractional change in concentration per unit distance from the source, decreased but stayed above 5 cm 1 (Fig. 1d), which is a threshold for directed cell migration.[5, 28] The time evolution of the concentration and gradient in the center of the device depends, among other variables, on the dimensions of the system. The concentration and specific gradient profile of the chemokine varies with position inside the chamber as shown in Figure 1c and 1d. We used an interative process to determine that for an experiment to be conducted within 24 h, appropriate dimensions for each chamber of the device are 3 mm in length and width and 1 mm in height, and the data shown are for a device with these dimensions.

Effect of dendritic cell activation state on directed migration in Transwell system

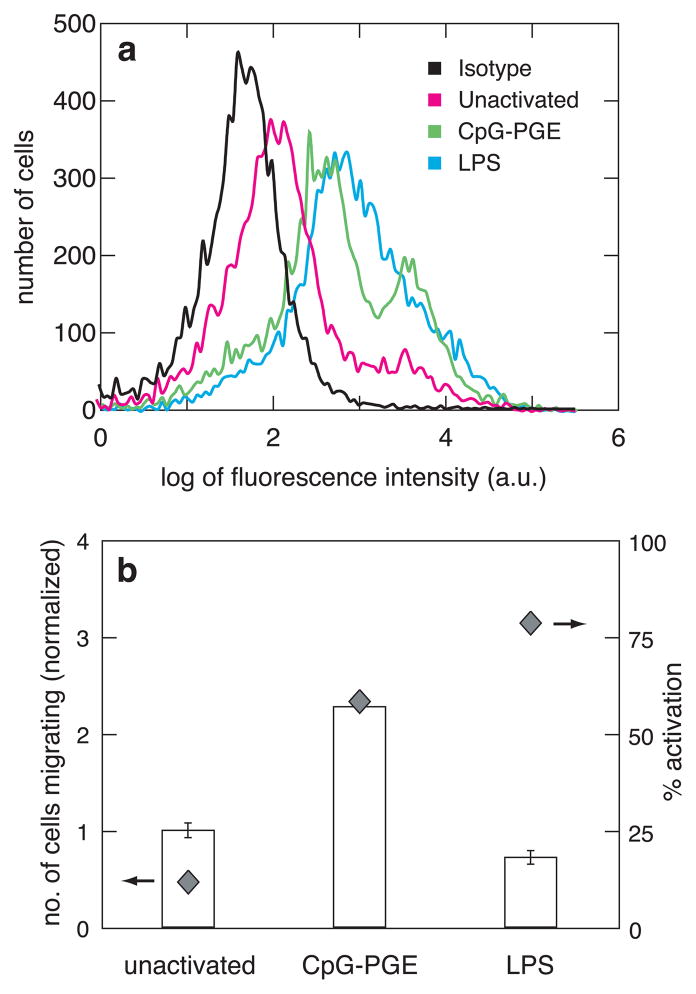

Dendritic cell migration studies were next performed using a traditional transwell system to determine a baseline relationship between cell activation and chemotaxis. Transwell systems are multi-well plate assemblies with porous membrane inserts used to culture cells. Transient gradients are created between the top of the wells (above membranes) and the bottom compartment by placing the chemotactic agent only in the bottom compartment and cells in the top compartment. The activation state and migratory abilities of unstimulated cells were compared to those stimulated by either cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS), two bacterially-derived agents commonly serving as surrogates for bacterial infection for in vitro studies. To analyze DC activation, the percentage of cells expressing CD86 on their surface was determined using fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). CpG treatment led to 59% CD86+ cells and LPS treatment led to 79% CD86+ cells (Figure 2a), suggesting that LPS is a better activating agent than CpG for dendritic cells. Next the migratory behavior of dendritic cells was monitored in response to the chemokine CCL19, following activation with either CpG or LPS. CpG induced more migration in activated cells compared with unactivated cells (Figure 2b), confirming that stimulated cells migrate faster towards CCL19. Even though LPS induced more CD86 expression in these cells than CpG, the migratory effect was comparable to that of the unactivated cells (Figure 2b). Because the transwell system and other traditional migration systems do not permit monitoring cell migration in real time, they limit one‘s ability to understand this behavior.

Figure 2.

(a) Activation of cells as measured by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). The different curves show the isotype staining of unactivated cells or the CD86 staining of unactivated, CpG-PGE-activated or LPS-activated cells. y-axis shows the number of cells expressing fluorescence and x-axis measures the log of fluorescence intensity of the cells from the fluorophore attached to the CD86 surface marker (quantifying activation) or the isotype control (measuring background fluorescence from cellular autofluorescence and nonantigen-specific binding). (b) Bars (left axis): The number of cells (normalized to the unactivated condition) migrating towards the chemokine (CCL19) under various activation conditions, as measured using the transwell assay. Diamonds (right axis): Percentage activation of cells under each condition measured against the isotype control.

Dendritic cell chemotaxis in the microfabricated migration system

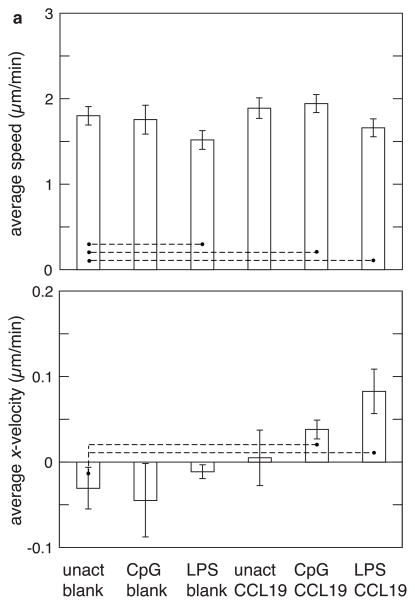

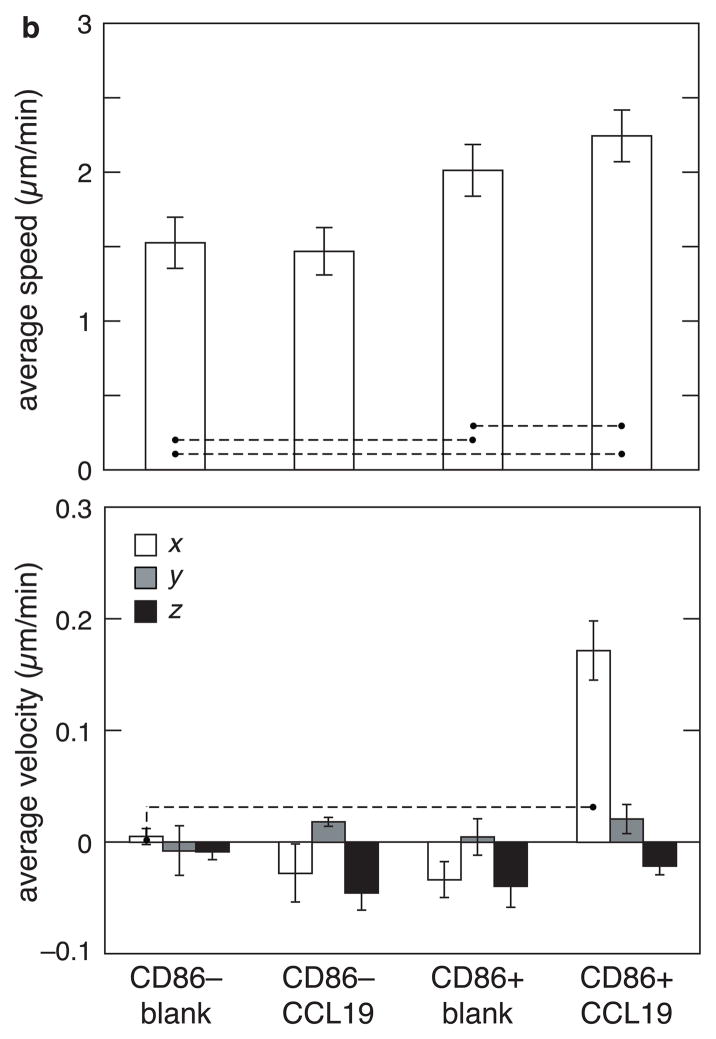

The advantages of utilizing a 3D-microfabricated system to study chemotaxis of activated dendritic cells include the ability to carry out precise measurements of cell migration speeds and velocities in real time. Dendritic cells were first placed in a collagen gel in the cell chamber, and their average velocity in the x-direction and overall speed were measured, with or without CCL19 in the chemokine chamber. For unactivated cells without chemokine (Unact Blank), the average x-velocity was not statistically different from zero, indicating a random walk process, as expected (Figure 3a). When CCL19 was introduced in the right chamber (Unact-CCL19), the average x-velocity remained approximately zero, indicating that CCL19 did not induce a chemotactic effect on unactivated cells. Activating cells in the absence of CCL19 (CpG-Blank) also did not lead to a migratory trend in any direction. However, when cells were both activated with CpG and exposed to CCL19 (CpG-CCL19), a weak but statistically-significant trend of cells migrating towards CCL19 was observed (Figure 3a). To better characterize the chemotactic effect of CCL19, cells activated with CpG were separated with FACS into homogeneous activated and unactivated cell populations, based on expression of the surface marker CD86. The migration behavior of the two cell populations was then analyzed. In the presence of CCL19 the average x-velocity of CD86+ cells increased dramatically (Figure 3b), and the x-velocity of these cells was approximately 4-fold greater than that of control CpG-activated cells. A substantial increase in the speed of CD86+ cells in the presence of the CCL19 as compared to CD86–cells was also observed (Figure 3b). To confirm a chemotactic effect on the x-velocity of CCL19 on CD86+ cells, and to rule out the possibility that these effects were simply due to a general increase in cell speed, the average y- and average z-velocities (directions perpendicular to the CCL19 gradient) were also measured for all conditions. The y- and z- velocities were all close to zero (Figure 3b). This finding indicates that the activation of cells specifically regulates the chemotactic migration of DCs towards the lymph-node derived chemokine, CCL19. In general, the speed of activated cells was higher than that of unactivated cells, and further increased in the presence of a chemotactic gradient.

Figure 3.

Effect of activation and presence of chemokine on the speed and velocity of dendritic cells as measured using the fabricated device. (a) Effect of the activation agents (CpG and LPS) and the presence of the chemokine (CCL19) on migration of dendritic cells. The average speed (top) and average x-velocity towards CCL19 source (bottom) of unactivated cells in the absence (unact blank) and presence of CCL19 (unact CCL19) was compared with that of CpG-activated and LPS-activated cells in the absence (CpG blank and LPS blank) and presence of CCL19 (CpG CCL19 and and LPS CCL19). (b) Separating the activated cells from unactivated cells (after CpG activation) using FACS sorting improves the signal-to-noise ratio. The average overall speed (top) and average x-velocity (bottom) of 100% unactivated cells in the absence (CD86-Neg-Blank) and presence of CCL19 (CD86-Neg-CCL19) was compared with that of 100% activated cells in the absence (CD86-Pos-Blank) and presence of CCL19 (CD86-Pos-CCL19). For comparison, average y- and average z-velocities were also plotted. For speed, statistical significance was evaluated for difference in values between the control (first condition of all the experiments) and the remaining conditions, and also between some of the pairs. For velocity, statistical significance was evaluated for non-zero velocity values in each condition and compared with the blank. For pairs connected by a dashed line p < 0.05. The error bars represent standard deviations.

As mentioned previously, experiments in the transwell system yielded anomalous results—high LPS activation yielded low migration. This anomaly can be further explored by comparing the migration of LPS-activated cells in the 3D-microfabricated system to that of CpG-activated cells. Calculation of the x-velocity towards CCL19 in the 3D system revealed a stronger chemotactic effect of LPS (Figure 3a), confirming the expected relation between the efficacy of LPS and CpG in DC activation and subsequent ability to migrate towards CCL19. However, the average speed of cells in the presence of LPS is lower than that of unstimulated cells (Figure 3a). This unanticipated finding—LPS exposure slows overall DC speed, but enhances directed migration—likely partially explains the confusing result found in transwell studies, as that system cannot independently measure these two facets of activated DC response to chemotactic gradients. The faster overall DC speed following exposure to CpG, as compared to LPS, probably leads to more cells crossing the transmembrane filter in a random and undirected manner. Further, the concentration and steepness of the gradient in a transwell setup are very different from that in a 3D-microfabricated system, which might also cause the LPS-activated cells to respond differently in the two migration assays.

Effect of architecture on cell chemotaxis

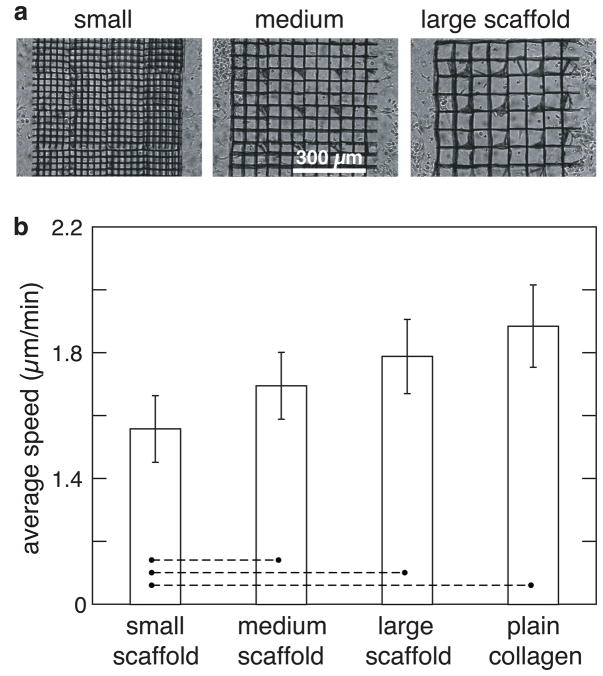

Finally, we examined how architectural features in a microfabricated 3D environment regulate the chemotactic response from activated cells, as cell migration through 3D structures is especially pertinent in cell therapies using a biomaterial carrier or scaffold.[29, 30] First, the random migration of dendritic cells embedded in a collagen gel infiltrated with scaffolds of different pore-sizes, i.e., 25-μm (small), 50-μm (medium), and 75-μm (large) features was analyzed (Figure 4). All scaffolds inhibited cell migration, as the average speed of the cells was lower within the scaffolds than in the same collagen gel outside the scaffold. Further, the speed of cells decreased with decreasing pore size due to increased obstruction from the matrix. The struts of scaffolds obstructed the movement of cells more frequently with decreasing pore size, causing a decrease in their speed. This result is similar to what we have shown earlier with HT1080 fibrosarcoma tumor cell line.[26]

Figure 4.

Scaffold effects on migration speed of dendritic cells. (a) Brightfield top-view image of different pore-sized scaffolds, referring to 25- m, 50- m and 75- m pore-sized scaffolds as ‘small’, ‘medium’ and ‘large’ scaffolds, respectively. (b) Comparison of the average speed of cells inside small, medium and large scaffolds. The speed was also measured for the condition in which cells were embedded in a gel without scaffold (plain-collagen). Statistical significance was evaluated for difference in values between small scaffold and other conditions. For pairs connected by a dashed line p < 0.05.

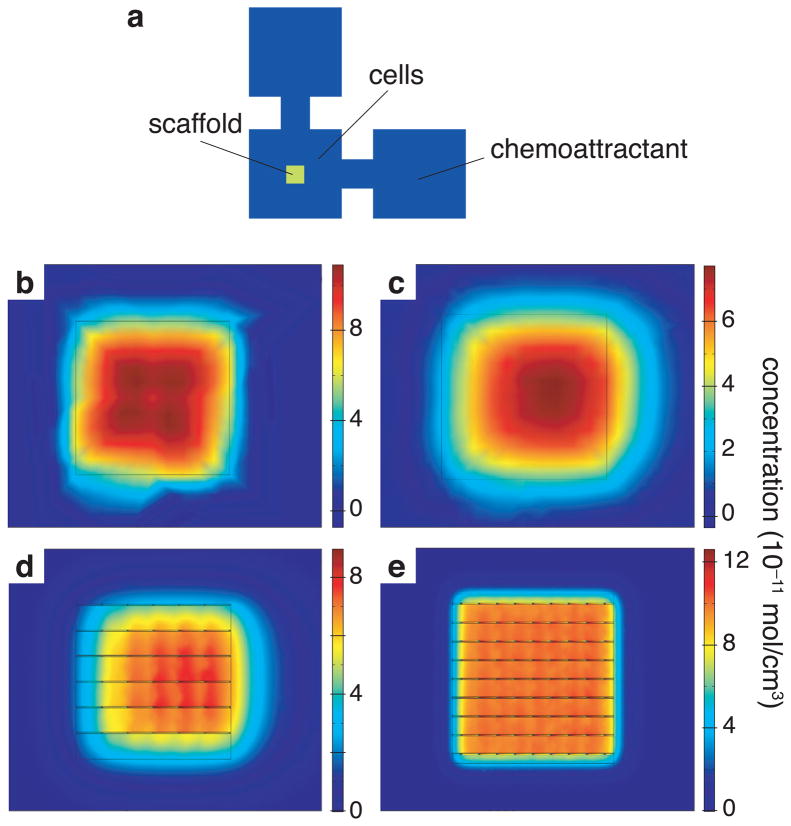

In order to probe the variable effects of alterations in architectural complexity of the microenvironment and chemokine gradients, a three dimensional advection-diffusion type continuum migration model was used to simulate how these two variables would interact.[31] This model predicted that an originally homogeneously-distributed cell population (Figure 5b) would be pulled towards the chemokine source over time, as expected. The mean x-coordinate of cell distribution inside a 75-μm pore-sized scaffold, when a chemokine gradient is present, was predicted to shift by 100 μm towards the chemokine source at the end of 8 h (Figure 5d). This shift was smaller than the 120-μm shift predicted in the absence of a scaffold (Figure 5c). Furthermore, 25-μm pore-sized scaffolds were predicted to allow a mean x-displacement of the cells of only 5 μm (Figure 5e). These modeling results suggest a hindering effect on chemotaxis that becomes more pronounced with a decrease in the pore size of the scaffolds. This is not due to the diffusion and distribution of chemokine, because the chemokine molecule is small enough to have a similar concentration gradient profile across different pore-sized scaffolds (analysis not shown).

Figure 5.

Calculated combined effect of chemotaxis and architecture on the directed migration of cells. (a) Schematic of chamber showing the outline of scaffold in the center of cell chamber and the position of cells and chemokine with respect to the scaffold; (b) simulated distribution of cells in the center region in the absence of scaffold but presence of chemotactic gradient at the beginning of the experiment and (c) at the end of 8 hours; (d) simulated distribution of cells at the end of 8 h in the presence of chemotactic gradient in large (75-µm pore size) scaffold and (e) in small (25-µm pore size) scaffold.

Chemotaxis experiments were next conducted using the range of scaffold architectural features shown by the modeling to impact cell migration. The average speeds, x-velocities, and cell distributions of activated cells in the presence and absence of chemokine were compared. The average speed decreased with decreasing pore size, and was highest in the absence of the scaffold (Figure 6), as predicted by the model. The cell speed in the large (75 μm) pore-sized scaffold was very similar to that in collagen without any scaffold, suggesting that constraining effects of architecture become negligible with pores around this size. Comparison of the average x-velocity for different conditions revealed that it was close to zero both within and outside the scaffolds in the absence of chemokine, as expected (Figure 6). In the presence of CCL19, the x- velocity decreased as the pore size decreases. The velocity of cells outside the scaffolds was much higher than that of cells inside the scaffolds, and this contrast was most pronounced in the smallest (25 μm) pore-sized scaffolds.

Discussion

In this work, a system was developed to study the effects of chemotaxis and architecture on dendritic cell migration using a combination of simulations and experiments. The results suggest that this system can separate the effects of speed and velocity in the process of migration, and the activation of dendritic cells affects their overall migration towards the lymph node chemokine, CCL19. Additionally, the architecture of the microenvironment of the cells strongly influences their chemotactic motility.

An L-shaped‘ device, which can be used to study the effects of two chemokines/growth factors on the migration of cells, was developed. If desired, the shape of the device could also be modified from an L-shape‘ to a Plus-shape‘ to study the role of conflicting gradients by placing more than two chemokines in various end chambers of the device. The dimensions of the device were chosen based on the values of absolute concentration and specific gradient of the chemokine as predicted by the simulation. Chemotaxis is driven by the detection of differences in attractant concentration over the length of the cell via cell surface chemokine receptors. In order for chemokines to effectively direct migration of cells, both the local concentration of the attractant and the specific gradient must take values within a limited range appropriate for support of chemotaxis.[5, 28] Some chemokines bind with high affinity to their receptors on cells; such chemokines function best at very low concentrations, as a very high chemokine concentration saturates the chemokines receptors and prevents detection of any gradient.[32] In addition to absolute concentration, the specific gradient is a critical factor in chemotaxis, and must be large enough for detection by cells. Theoretical[5] and experimental[5, 28] analyses suggest that soluble chemokines must form a specific gradient on the order of 5–10 cm−1 to elicit directed migration, corresponding to a minimum 0.5–1.0% change in attractant concentration over the length of a typical cell (10 μm diameter). This prediction is consistent with the results of this study, as a specific concentration of 5 cm−1 efficiently drove dendritic cell chemotaxis.

Dendritic cells provide a vital link to the response of other immune cells to the environment. The results of these studies demonstrate that one can quantitatively control the directed migration of dendritic cells by optimizing their activation state and by localizing chemotactic gradients. Interestingly, the effect of dendritic cell activation on average cell speed varied significantly depending on the activation agent used. CpG increased the average cell speed (random cell motion), whereas LPS yielded a decrease. Cells activated by either cue exhibited chemotaxis towards a source of CCL19. The increased magnitude of chemotaxis (x-velocity) with LPS treatment was likely due to these cells not migrating as randomly as CpG-activated cells, yielding a more specific response to the cytokine. The lack of correlation between activation state and chemotaxis found in the transwell system suggests that, although standard migration assays may be simpler, they can be misleading, as they do not allow one to separately analyze random versus directed cell migration.

The results of these studies demonstrate a striking interplay between architectural features of the material through which the cells are migrating, and chemokine gradients in directing dendritic cell migration. First, the random motility of cells migrating inside scaffolds was found to decrease, in both simulations and experiments, as the pore size decreased, likely due to the hindrance to cell movement from scaffolds. As the pore size inside the scaffold increased, however, the cell movement started to resemble migration outside of scaffolds. This suggests that, beyond a particular size range, the presence of a scaffold does not have a significant effect on chemotactic cell migration. Directed cell migration in response to a CCL19 gradient, as measured by the average x-velocity of cells, also decreased as the pore size decreased, slowing cell migration towards the chemokine source. Even when a matrix structure is not physically tortuous enough to affect chemokine distribution, it can still hinder cell locomotion, and architectural features can play a dominating factor in the chemotactic migration of cells.

Conclusion

A 3D ex vivo system with chemokine gradients was developed to study the interplay of matrix architecture and chemokine gradients in directed cell migration. The major strengths of this system are the ability to quantify both random cell migration and chemotaxis, allowing one to clarify data arising from traditional migration assays. The finding that matrix architecture dramatically affects chemotaxis is likely to impact current approaches in vaccine development which involve immune cell trafficking in vitro and in vivo,[33, 34] and tissue engineering strategies that rely on progenitor cell chemotaxis.[35–37]

Acknowledgments

The research described in this paper was supported by the NSF-sponsored Materials Research Science and Engineering Center under contract DMR-0213805, NIH under contract R37 DE013033, NSF under contract CBET-0854288 and BASF funding. P.T. conceived of the basic idea for this work, designed and carried out the experiments, and analyzed the results. D.M. and E.M. supervised the research, analysis of the data, and the development of the manuscript. P.T. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; all authors subsequently took part in the revision process and approved the final copy of the manuscript. The authors would like to thank V. Nuzzo, P. Peng and J. Dowd for providing feedback on the manuscript throughout its development.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Driever W, Nussleinvolhard C. A gradient of bicoid protein in drosophila embryos. Cell. 1988;54(1):83–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ochoa O, Torres FM, Shireman PK. Chemokines and diabetic wound healing. Vascular. 2007;15(6):350–5. doi: 10.2310/6670.2007.00056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyden S. Chemotactic effect of mixtures of antibody and antigen on polymorphonuclear leucocytes. J Exp Med. 1962;115(3):453. doi: 10.1084/jem.115.3.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson RD, Quie PG, Simmons RL. Chemotaxis under agarose - new and simple method for measuring chemotaxis and spontaneous migration of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes and monocytes. J Immunol. 1975;115(6):1650–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zigmond SH. Ability of polymorphonuclear leukocytes to orient in gradients of chemotactic factors. J Cell Biol. 1977;75(2):606–16. doi: 10.1083/jcb.75.2.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zigmond SH, Hirsch JG. Leukocyte locomotion and chemotaxis - new methods for evaluation and demonstration of a cell-derived chemotactic factor. J Exp Med. 1973;137(2):387–410. doi: 10.1084/jem.137.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zicha D, Dunn GA, Brown AF. A new direct-viewing chemotaxis chamber. J Cell Sci. 1991;99:769–75. doi: 10.1242/jcs.99.4.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerisch G, Keller HU. Chemotactic reorientation of granulocytes stimulated with micropipets containing fMet-Leu-Phe. J Cell Sci. 1981;52:1–10. doi: 10.1242/jcs.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosoff WJ, McAllister R, Esrick MA, Goodhill GJ, Urbach JS. Generating controlled molecular gradients in 3D gels. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;91(6):754–9. doi: 10.1002/bit.20564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells A, Kassis J, Solava J, Turner T, Lauffenburger DA. Growth factor-induced cell motility in tumor invasion. Acta Oncol. 2002;41(2):124–30. doi: 10.1080/028418602753669481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkinson PC. Assays of leukocyte locomotion and chemotaxis. J Immunol Methods. 1998;216(1–2):139–53. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao X, Shoichet MS. Defining the concentration gradient of nerve growth factor for guided neurite outgrowth. Neuroscience. 2001;103(3):831–40. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher PR, Merkl R, Gerisch G. Quantitative-analysis of cell motility and chemotaxis in dictyostelium-discoideum by using an image-processing system and a novel chemotaxis chamber providing stationary chemical gradients. J Cell Biol. 1989;108(3):973–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.3.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dertinger SKW, Chiu DT, Jeon NL, Whitesides GM. Generation of gradients having complex shapes using microfluidic networks. Anal Chem. 2001;73(6):1240–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeon NL, Dertinger SKW, Chiu DT, Choi IS, Stroock AD, Whitesides GM. Generation of solution and surface gradients using microfluidic systems. Langmuir. 2000;16(22):8311–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker GM, Sai JQ, Richmond A, Stremler M, Chung CY, Wikswo JP. Effects of flow and diffusion on chemotaxis studies in a microfabricated gradient generator. Lab Chip. 2005;5(6):611–8. doi: 10.1039/b417245k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392(6673):245–52. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sozzani S, Allavena P, D'Amico G, Luini W, Bianchi G, Kataura M, et al. Cutting edge: Differential regulation of chemokine receptors during dendritic cell maturation: A model for their trafficking properties. J Immunol. 1998;161(3):1083–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yanagihara S, Komura E, Nagafune J, Watarai H, Yamaguchi Y. EBI1/CCR7 is a new member of dendritic cell chemokine receptor that is up-regulated upon maturation. J Immunol. 1998;161(6):3096–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forster R, Schubel A, Breitfeld D, Kremmer E, Renner-Muller I, Wolf E, et al. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell. 1999;99(1):23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Understanding dendritic cell and T-lymphocyte traffic through the analysis of chemokine receptor expression. Immunol Rev. 2000;177:134–40. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.17717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lutz MB, Kukutsch N, Ogilvie ALJ, Rossner S, Koch F, Romani N, et al. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J Immunol Methods. 1999;223(1):77–92. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali OA, Mooney DJ. Sustained GM-CSF and PEI condensed pDNA presentation increases the level and duration of gene expression in dendritic cells. J Control Release. 2008;132(3):273–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luft T, Jefford M, Luetjens P, Toy T, Hochrein H, Masterman KA, et al. Functionally distinct dendritic cell (DC) populations induced by physiologic stimuli: prostaglandin E-2 regulates the migratory capacity of specific DC subsets. Blood. 2002;100(4):1362–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scandella E, Men Y, Gillessen S, Forster R, Groettrup M. Prostaglandin E2 is a key factor for CCR7 surface expression and migration of monocyte-derived denctritic cells. Blood. 2002;100(4):1354–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tayalia P, Mendonca CR, Baldacchini T, Mooney DJ, Mazur E. 3D cell-migration studies using two-photon engineered polymer scaffolds. Adv Mater. 2008;20(23):4494–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krautwald S, Ziegler E, Forster R, Ohl L, Amann K, Kunzendorf U. Ectopic expression of CCL19 impairs alloimmune response in mice. Immunology. 2004;112(2):301–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moghe PV, Nelson RD, Tranquillo RT. Cytokine-stimulated chemotaxis of human neutrophils in a 3-D conjoined fibrin gel assay. J Immunol Methods. 1995;180(2):193–211. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)00314-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coutu DL, Yousefi AM, Galipeau J. Three-dimensional porous scaffolds at the crossroads of tissue engineering and cell-based gene therapy. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108(3):537–46. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Y, El Haj AJ. Biodegradable scaffolds - delivery systems for cell therapies. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2006;6(5):485–98. doi: 10.1517/14712598.6.5.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.James N, Kara K, Richard W, Elizabeth OQ, Matthew W, Barbara B, et al. Proceedings of the 2007 summer computer simulation conference. San Diego, California: Society for Computer Simulation International; 2007. A discrete cell migration model. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varona R, Zaballos A, Gutierrez J, Martin P, Roncal F, Albar JP, et al. Molecular cloning, functional characterization and mRNA expression analysis of the murine chemokine receptor CCR6 and its specific ligand MIP-3 alpha. FEBS Lett. 1998;440(1–2):188–94. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01450-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali OA, Huebsch N, Cao L, Dranoff G, Mooney DJ. Infection-mimicking materials to program dendritic cells in situ. Nat Mater. 2009;8(2):151–8. doi: 10.1038/nmat2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hori Y, Winans AM, Huang CC, Horrigan EM, Irvine DJ. Injectable dendritic cell-carrying alginate gels for immunization and immunotherapy. Biomaterials. 2008;29(27):3671–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burkus JK, Transfeldt EE, Kitchel SH, Watkins RG, Balderston RA. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of anterior lumbar interbody fusion using recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. Spine. 2002;27(21):2396–408. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200211010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hill E, Boontheekul T, Mooney DJ. Regulating activation of transplanted cells controls tissue regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(8):2494–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506004103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silva EA, Kim ES, Kong HJ, Mooney DJ. Material-based deployment enhances efficacy of endothelial progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(38):14347–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803873105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]