The experimental anti-tumor compound, DMXAA, shown previously to be a potent IFN-β-inducer in vitro, exhibits antiviral activity in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: macrophage, influenza

Abstract

The 2009 outbreak of pandemic H1N1 influenza, increased drug resistance, and the significant delay in obtaining adequate numbers of vaccine doses have heightened awareness of the need to develop new antiviral drugs that can be used prophylactically or therapeutically. Previously, we showed that the experimental anti-tumor drug DMXAA potently induced IFN-β but relatively low TNF-α expression in vitro. This study confirms these findings in vivo and demonstrates further that DMXAA induces potent antiviral activity in vitro and in vivo. In vitro, DMXAA protected RAW 264.7 macrophage-like cells from VSV-induced cytotoxicity and moreover, inhibited replication of influenza, including the Tamiflu®-resistant H1N1 influenza A/Br strain, in MDCK cells. In vivo, DMXAA protected WT C57BL/6J but not IFN-β−/− mice from lethality induced by the mouse-adapted H1N1 PR8 influenza strain when administered before or after infection. Protection was accompanied by mitigation of weight loss, increased IFN-β mRNA and protein levels in the lung, and significant inhibition of viral replication in vivo early after DMXAA treatment. Collectively, this study provides data to support the use of DMXAA as a novel antiviral agent.

Introduction

Influenza virus infection continues to be a major health concern globally and is associated with high morbidity and mortality. Seasonal influenza causes ∼36,000 deaths and ∼226,000 hospitalizations annually in the United States alone [1, 2]. Rapid antigenic changes of the virus and the resultant yearly emergence of new influenza strains are responsible for the seasonal epidemics and occasional pandemics that often require hospitalization.

Antiviral medications currently licensed in the United States for the treatment of influenza infection include the adamantane M2 ion channel blockers amantadine and rimantadine and the neuraminidase inhibitors oseltamivir (Tamiflu®) and zanamivir (Relenza®) [3, 4]. However, viral resistance to the adamantanes has become common [5]. For example, H3N2 seasonal influenza strains have been resistant to the adamantanes since 2005. Resistance to oseltamivir is less common [6]; however, the dominant circulating seasonal H1N1 influenza strain in the United States as of 2009, prior to the emergence of the swine-origin pandemic H1N1 influenza strain, was completely oseltamivir-resistant [7]. Zanamivir-resistant influenza A variants have been isolated from immunocompromised patients [8]. In addition, as a result of poor bioavailability, zanamivir must be administered directly into the respiratory tract via an inhalation device, and thus, this drug is generally not recommended for use in persons with underlying lung disease, e.g., asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The recent emergence of the swine-origin pandemic H1N1 influenza strain resulted in the issuance of an Emergency Use Authorization for i.v. peramivir, an investigational neuraminidase inhibitor, to be used in hospitalized patients with severe and potentially fatal H1N1 influenza infection by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [9]. However, the efficacy and biosafety profile of peramivir are still uncertain.

Thus, as a consequence of an increased appearance of drug-resistant influenza strains and some unwanted side-effects seen in patients treated with these approved antiviral drugs, e.g., CNS side-effects, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and bronchospasm, there remains an urgent need to incorporate novel anti-influenza drugs into the current armamentarium and therefore, provide more options for antiviral prophylaxis or therapy. Currently, IFNs, originally identified for their antiviral activity [10, 11], are used clinically for treatment of certain viral diseases, e.g., hepatitis B and C infections [12, 13], as well as noninfectious illnesses such as multiple sclerosis and malignant melanoma [14, 15]. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, type I IFN was available as a nasal spray in Moscow pharmacies for prophylaxis and treatment of influenza [16, 17]. The reported success attracted the interest of Western scientists who subsequently tested these claims using human volunteers, stronger natural preparations of type I IFN, and standardized influenza challenges [18, 19]. The therapeutic effects on influenza-induced disease were minimal, but after only one prophylactic treatment, IFN resulted in a marked delay in the total clinical score in IFN-treated patients [18], suggesting the presence of an inhibitory effect on symptoms that was not sustained over time. Common, undesirable side-effects of IFN administration include injection-site reactions, alterations in liver enzymes, and lymphopenia, as well as flu-like symptoms (e.g., fever, fatigue, headache, muscle aches, etc.). Sustained IFN-β treatment also induces the generation of neutralizing antibodies, thus limiting its efficacy and potency in vivo. Therefore, induction of endogenous IFN-β in tissues targeted by viruses such as influenza should be considered as a strategy that is likely to be more effective with fewer side-effects than exogenous IFN administration.

We reported originally that DMXAA, a compound originally developed as an anti-cancer drug [20], is a much more potent inducer of IFN-β and the IFN-β-inducible chemokine, IFN-inducible protein 10, in mouse peritoneal macrophages than the prototype TLR4 agonist LPS. In contrast, LPS induced much higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines, e.g., TNF-α and IL-1β, and lower levels of IFN-β than DMXAA [21]. Enhanced induction of IFN-β by DMXAA was a result of augmented TBK-1-mediated phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of IRF-3 [22], a key transcription factor for activation of the IFN-β promoter [23]. Given the strong capacity for DMXAA to induce IFN-β and the well-characterized antiviral properties of IFN, we hypothesized that DMXAA, an experimental anti-tumor agent with an excellent safety profile in humans [24], may represent a novel, potent IFN-β-inducing agent that may be used to mitigate virus-induced disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Six- to 10-week-old WT C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). IFN-β−/− mice (backcrossed >N8 on a C57BL/6 background) were the kind gift of Dr. Eleanor Fish (University of Toronto, Canada) and were bred at University of Maryland, Baltimore (Maryland, USA). All experiments were conducted with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval.

Reagents

DMXAA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) stocks were prepared at 10 mg/ml in 7.5% sodium bicarbonate and kept frozen at –20°C. Tamiflu® (oseltamivir phosphate; Roche Laboratories Inc., Nutley, NJ, USA) and Relenza® (zanamivir; GlaxoSmithKline, Chapel Hill, NC, USA) were dissolved in distilled water at concentrations of 1.75 mg/ml and 0.5 mg/ml, respectively, at the time of use. Protein-free Escherichia coli K235 LPS was prepared as reported previously [25].

Viruses

VSV (Indiana strain) was propagated as described previously [26]. Influenza A/Wuhan virus and Tamiflu®-resistant influenza A/Br virus were propagated in MDCK cells as described previously [27]. Mouse-adapted H1N1 influenza PR8 virus (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) was grown in the allantoic fluid of 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs, as described previously [28].

In vitro and in vivo viral infections

RAW 264.7 macrophages were cultured as described previously [22] and plated at 1 × 105 cells/well in a 96-well plate (Nalge-Nunc International, Rochester, NY, USA). After overnight incubation at 37°C, cells were treated with medium containing vehicle or DMXAA (100 μg/ml). After 6 h, the culture medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM containing VSV at the indicated MOI for 1 h. Cells were then maintained in complete DMEM with 10% FBS. Twenty-four hours later, cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 10% buffered formalin (Sigma-Aldrich), and rinsed thoroughly with distilled H2O. Adherent cells were stained with crystal violet [29].

Two assays were used to determine the ability of DMXAA to protect cultured cells against influenza infection. MDCK cells were plated and incubated overnight at 37°C. Antiviral activity of DMXAA was assessed by pre-incubating 1 × 103 TCID50 influenza virus (A/Wuhan or A/Br) with the indicated concentrations of DMXAA for 1 h at 37°C. Positive controls were Tamiflu® (0.1–10 μg/ml) and Relenza® (0.12 μg/ml). MDCK cells were then inoculated with the pre-incubated mixture (virus pretreatment). After 96 h, cells were stained with crystal violet, and the absence or presence of CPE was determined at 40× magnification. In addition, antiviral activity was assessed by addition of DMXAA to the cell culture 1 h before inoculation with 1 × 103 TCID50 (“cell pretreatment”). Cells were maintained and CPE quantified as described for the virus pretreatment assay.

To confirm the data obtained using CPE as an end-point, virus titers were obtained from supernatants of infected MDCK cells, as described previously [27], and are expressed as TCID50/ml.

In vivo treatments

To test the efficacy of DMXAA in vivo, mice were injected i.p. with 0.5 ml saline or DMXAA (25 mg/kg; ∼500 μg/mouse). After 3 h, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and infected i.n. with 50 μl PR8 influenza (200 p.f.u./mouse). A second i.p. dose of saline or DMXAA was given on Day 2 p.i. (∼48 h). Survival was monitored daily for 14 days. Weight loss was monitored on individual mice after infection. In some experiments, mice were killed after treatment to harvest lungs for analysis of gene expression or viral titers. Where indicated, DMXAA was administered 3 h after infection and on Day 2 p.i.

qPCR

qPCR was carried out for the detection of mRNA expression of IFN-β, TNF-α, and the housekeeping gene HPRT, as described previously [22, 25].

RESULTS

DMXAA is a more potent inducer of IFN-β and a relatively poor inducer of TNF-α than LPS in vivo

We reported previously that DMXAA was a potent and specific inducer of the TBK-1–IRF-3–IFN-β axis [22], a major signaling pathway activated by several innate-immune PRRs, e.g., TLR4, TLR3, RIG-I, and MDA-5 [30]. The cellular target of DMXAA is unknown; however, we have excluded all known TLRs, RIG-I, and MDA-5 [22], as well as the DNA-dependent activator of IRF [31] (unpublished observations). In murine macrophages, DMXAA had a minimal effect on NF-κB activation [22]. In comparison, LPS elicited significantly higher levels of NF-κB-dependent proinflammatory cytokines, e.g., TNF-α and IL-1β, which correlated with rapid degradation of IκBα and increased nuclear NF-κB translocation [21, 22]. Furthermore, under conditions in which LPS strongly activated MAPKs within 15 min, DMXAA had no measurable effect over a 2-h time course [22]. Recently, we have found that IFN-β mRNA is similarly up-regulated by DMXAA in primary human monocytes (data not shown).

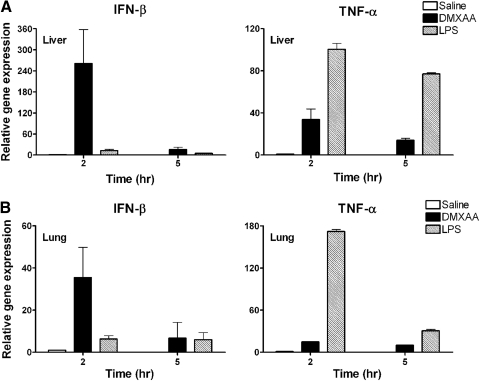

Given the potency of DMXAA and its apparent preferential capacity for IFN-β induction in vitro, we sought to extend these findings by comparing the relative ability of DMXAA and LPS to induce expression of IFN-β and TNF-α in vivo. DMXAA (25 mg/kg) or LPS (25 μg/mouse) was administered to WT C57BL/6J mice i.p., followed by measurement of IFN-β and TNF-α mRNA expression by qPCR in livers (Fig. 1A) and lungs (Fig. 1B) at 2 and 5 h. This dose of DMXAA is well-tolerated by mice and well below that recommended for human use (i.e., 1000–2000 mg/m2 [32]). The data in Fig. 1 mirrored the previously published in vitro data. In vivo, DMXAA was a more potent inducer of IFN-β mRNA and a relatively poor inducer of TNF-α mRNA when compared with LPS.

Figure 1. Differential induction of IFN-β and TNF-α mRNA expression by DMXAA and LPS in vivo.

C57BL6/J mice were injected i.p. with 0.5 ml saline (n=6), DMXAA (25 mg/kg; ∼500 μg/mouse; n=7), or E. coli LPS (25 μg/mouse; n=7). At 2 h and 5 h (n=3 for each treatment group) after treatment, livers (A) and lungs (B) were extracted, and relative gene expression was analyzed by qPCR and normalized to HPRT. Results represent the mean ± sd.

DMXAA treatment inhibits VSV-induced cytotoxicity and influenza virus replication in vitro

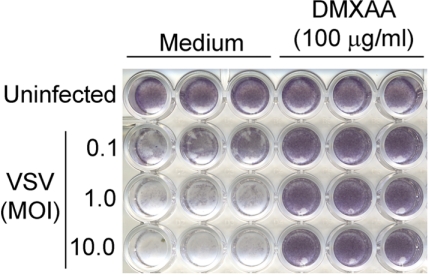

Although originally developed as an anti-tumor agent [20, 24, 33], the ability of DMXAA to induce such a strong IFN-β response in vitro and in vivo suggested the possibility that DMXAA might alternatively be used as an antiviral agent. As much of our earlier work had been carried out in murine macrophages [21, 22], we next tested the ability of DMXAA to induce antiviral activity against VSV infection in the mouse macrophage cell line RAW 264.7. In murine macrophages, we have tested DMXAA up to 1000 μg/ml and have found no detectable cellular toxicity, as evidenced by normal cellular morphology, no loss of trypan blue exclusion, and the failure of DMXAA to affect expression of “housekeeping genes”, such as hprt, assessed by qPCR (data not shown) [21, 22]. RAW 264.7 macrophages were pretreated with medium or DMXAA for 6 h and then infected with VSV at a MOI of 0.1, 1.0, or 10 for 24 h. Virus-induced cell death was measured as decreased crystal violet staining of cell monolayers as a result of the detachment of dead macrophages [34]. As shown in Fig. 2, DMXAA-treated cells were protected from VSV-induced cytotoxicity at all MOIs in contrast to medium-pretreated macrophages. This provided the first evidence that DMXAA could directly induce an antiviral state in macrophages.

Figure 2. DMXAA protects from VSV infection in vitro.

RAW 264.7 cells were treated with DMXAA (100 μg/ml) for 6 h, washed, and infected with VSV with increasing MOIs as indicated. After 24 h, cells were washed with PBS, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, and stained with crystal violet. The results are derived from a single representative experiment (n=3).

DMXAA induces antiviral activity against influenza in vitro

To test whether the antiviral effect of DMXAA extended to other IFN-sensitive viruses and in nonmacrophage cell types, an in vitro model of influenza virus infection in MDCK cells was next used. MDCK cells were plated and divided into two groups. One group of cells was treated with increasing DMXAA concentrations that had been premixed with human H3N2 influenza A/Wuhan virus for 1 h prior to addition of the mixture to cells (virus pretreatment). The second group of cells was first pretreated with DMXAA for 1 h (cell pretreatment column; Table 1) and then infected with this same strain of influenza virus. Table 1 indicates that DMXAA induces a powerful antiviral state in the cultured cells over a broad concentration range (6.25–100 μg/ml) that inhibits viral replication, as measured by decreased CPE, of a highly infectious influenza virus strain, whether present concurrently with or prior to virus infection without affecting cellular metabolism (i.e., luciferase gene reporter activity in MDCK cells treated with these same concentrations of DMXAA was identical to the activity of vehicle-treated cells; data not shown). Indeed, protection from influenza virus infection afforded by DMXAA was comparable with that induced by Tamiflu® (oseltamivir) and Relenza® (zanamivir), the two neuraminidase inhibitors currently approved for use against influenza infection in the United States. Thus, the data shown in Fig. 2 and Table 1 provide strong evidence that in vitro treatment of cells with DMXAA leads to a protective antiviral state.

Table 1. DMXAA Inhibits Influenza A/Wuhan Replication In Vitro.

| Drug (μg/ml) | Virus pretreatment | Cell pretreatment |

|---|---|---|

| DMXAA (100) | + + + +a | + + + + |

| DMXAA (25) | + + + + | + + + + |

| DMXAA (6.25) | + + + + | + + + + |

| DMXAA (1.56) | + − + − | + + + − |

| DMXAA (0.39) | − − − − | − − + − |

| Tamiflu® (0.1) | − + + + | |

| Relenza® (0.12) | − + + + | |

| Virus control | − − − − |

+ and − indicate the presence or absence, respectively, of antiviral activity measured in each of quadruplicate cultures by a plaque assay in MDCK cells.

DMXAA protects cells against a Tamiflu®-resistant influenza replication in vitro

Influenza is known to develop resistance to antiviral agents that target neuraminidase. In particular, oseltamivir (Tamiflu®)-resistant, seasonal H1N1 influenza virus strains are now rampant globally [35, 36] and have become an increasing health problem. We sought to determine if DMXAA could be effective against Tamiflu®-resistant influenza virus. Using a Tamiflu®-resistant strain of influenza, A/Br, we tested the efficacy of DMXAA treatment in vitro in the MDCK culture system. As expected, influenza A/Wuhan, but not the resistant A/Br strain, was inhibited by Tamiflu® (Table 2). Importantly, DMXAA effectively inhibited growth of both strains of influenza (Table 2), demonstrating the potential of DMXAA for treatment of drug-resistant strains of human influenza.

Table 2. DMXAA Inhibits Tamiflu®-Resistant Influenza A/B Replication In Vitro.

| Drug (μg/ml) | A/B |

A/Wuhan |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus pretreatment | Cell pretreatment | Virus pretreatment | Cell pretreatment | |

| DMXAA (25) | + + + +a | + + + + | + + + + | + + + + |

| DMXAA (6.25) | + + + + | + + + + | + + + + | + + + + |

| Tamiflu® (10) | − − − − | − − − − | + + + + | + + + + |

| Tamiflu® (2.5) | − − − − | − − − − | + + + + | + + + − |

+ and − indicate the presence or absence, respectively, of antiviral activity measured in each of quadruplicate cultures by a plaque assay in MDCK cells.

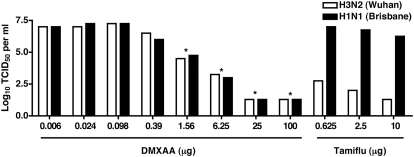

To confirm and extend these observations, MDCK cells were treated with DMXAA or Tamiflu® and infected with the Tamiflu®-sensitive or Tamiflu®-resistant strain. Supernatants derived from these cultures were assayed for viral titers. Consistent with the data shown in Table 1, as little as 1.56 μg/ml DMXAA inhibited viral replication of the Tamiflu®-sensitive strain, as well as the Tamiflu®-resistant influenza (Fig. 3). The controls in Fig. 3 indicate that Tamiflu® failed to reduce virus titers in the cells infected with the resistant strain. These data further indicate that protection from CPE correlates well with decreased viral titer.

Figure 3. DMXAA inhibits influenza A/Wuhan and Tamiflu®-resistant influenza A/Br replication in vitro.

Increasing concentration of DMXAA and Tamiflu® was incubated with the indicated viruses (3.0 Log10 TCID50) for 1 h at room temperature and then added to confluent cultures of MDCK cells. Twenty-four hours later, supernatants were collected for measurement of viral titers by the TCID50 assay. Each bar represents the mean of four wells; *P < 0.05.

DMXAA protects WT C57BL/6J, but not IFN-β null, mice from mouse-adapted, influenza-induced lethality

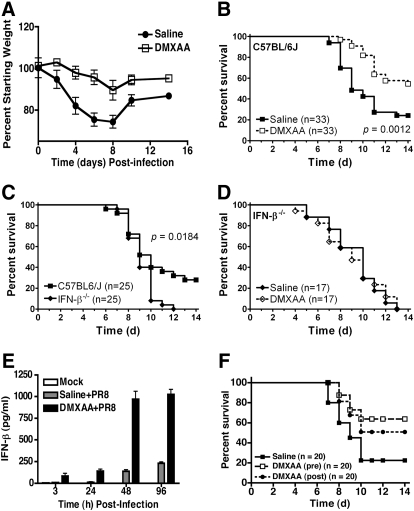

Next, we sought to determine if in vivo administration of the potent IFN-β inducer DMXAA would protect mice against lethal infection with a mouse-adapted H1N1 influenza virus, strain PR8. In Fig. 4, A–E, saline or DMXAA was administered i.p. 3 h prior to i.n. infection with influenza virus, followed by saline or DMXAA treatment 2 days later. Weight loss is often used as a surrogate marker for influenza-induced disease in mice. Fig. 4A shows that influenza infection of WT C57BL/6 mice caused a marked decrease in weight loss that reached its nadir 8 days after infection, the point at which control mice begin to die and after which survivors regain weight. DMXAA administration led to significantly less weight loss in influenza-infected mice. Consistent with our recent report [25], saline-treated WT C57BL/6J mice infected i.n. with 200 p.f.u. mouse-adapted H1N1 influenza PR8 virus exhibited ∼20% survival over the course of 14 days, whereas DMXAA-treated mice were protected significantly (∼60% survival; P=0.0012; Fig. 4B). This supports the hypothesis that the DMXAA may also be used as an antiviral agent in vivo.

Figure 4. IFN-β-dependent, DMXAA-mediated protection of mice against influenza-induced lethality.

(A) DMXAA protects C57BL/6J mice against influenza-induced weight loss. WT C57BL/6J mice were injected i.p. with saline or DMXAA (25 mg/kg; ∼500 μg/mouse). Three hours later, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and infected i.n. with 50 μl mouse-adapted H1N1 influenza virus (PR8; 200 p.f.u./mouse). Mice received a second i.p. dose of saline or DMXAA (25 mg/kg; ∼500 μg/mouse) on Day 2 after infection. Weight loss was monitored daily for 14 days. Results are compiled from three separate experiments. (B) DMXAA protects C57BL/6J mice against influenza-induced lethality. WT C57BL/6J mice were treated as in A and survival monitored daily for 14 days. Results are compiled from five separate experiments. (C) IFN-β-deficient mice are hypersusceptible to influenza virus-induced lethality. WT C57BL/6J and IFN-β−/− mice were infected with influenza virus as described in A and survival monitored daily for 14 days. Data are compiled from three separate experiments. (D) DMXAA fails to protect IFN-β−/− mice from influenza-induced lethality. WT C57BL/6 or IFN-β−/− mice were treated with saline or DMXAA and infected with influenza virus as described in A. Results are compiled from three separate experiments. The total numbers of mice in each group are shown in parentheses. (E) DMXAA-treated mice have increased IFN-β levels in lung homogenates. C57BL/6J mice were injected i.p. with saline or DMXAA. Three hours later, mice were infected i.n. with 50 μl mouse-adapted H1N1 influenza virus. Mice were killed 3, 24, 48, and 96 h p.i., and lungs were harvested to measure IFN-β protein by ELISA. Results are compiled from two separate experiments (mean±sem). (F) DMXAA provides protection when administered therapeutically. WT C57BL/6J mice were injected i.p. with saline or DMXAA (25 mg/kg; ∼500 μg/mouse) 3 h prior to or 3 h after i.n. infection with mouse-adapted H1N1 influenza virus (PR8; 200 p.f.u./mouse). Mice received a second i.p. dose of saline or DMXAA (25 mg/kg; ∼500 μg/mouse) on Day 2 after infection. Survival was monitored daily for 14 days. Data are compiled from two separate experiments.

To determine if IFN-β contributed to DMXAA-mediated protection against influenza infection, WT C57BL/6J and IFN-β−/− mice were administered saline or DMXAA and then infected with influenza virus. Fig. 4C shows that WT mice that express an intact IFN-β gene were significantly more resistant to influenza infection than IFN-β−/− mice, even in the absence of DMXAA treatment. More importantly, DMXAA administration did not increase survival in influenza-infected IFN-β−/− mice (Fig. 4D), indicating that IFN-β is central to the protection afforded to mice administered DMXAA. Consistent with these observations, mice treated with DMXAA and infected with influenza PR8 virus exhibited significantly increased levels of IFN-β mRNA (data not shown) and protein (Fig. 4E) in lungs than saline-treated, infected mice. Within 1 day of treatment with DMXAA, virus titers in lung homogenates were reduced ∼25-fold (from 5.3 Log10 to 4.7 Log10 TCID50/ml). Collectively, these data indicate that the protection afforded by DMXAA against influenza virus infection of WT mice is IFN-β-dependent.

Finally, we assessed the potential of DMXAA as a therapeutic agent for influenza infection. Consistent with the data in Fig. 4B, Fig. 4F shows that mice, which had been treated with DMXAA 3 h prior to infection, were protected significantly (∼62% survival; P=0.0013). Mice administered DMXAA i.p. 3 h after infection were also protected significantly (∼51% survival; P=0.0047) in comparison with saline-treated, infected mice (Fig. 4F). There was no significant difference in survival between treating mice 3 h before or 3 h after infection (P>0.05). Taken together, the data further support DMXAA as an antiviral prophylactic and therapeutic agent.

DISCUSSION

In summary, our data provide strong support for the hypothesis that DMXAA, a small molecule that has shown promise as an anti-tumor agent, may be used as a novel antiviral agent against human influenza and perhaps other IFN-sensitive viruses. Together, our data support the conclusion that DMXAA is an immunomodulatory agent that affords protection from virus-induced morbidity and mortality via induction of a potent “antiviral state.” Through its activation of IRF-3-mediated transcription and particularly, of IFN-β, DMXAA induces the expression of a number of known antiviral cytokines and chemokines [22]. As such, IFN-β amplifies and diversifies the antiviral response, providing the host with a primed defense against invading virus. Importantly, we showed that DMXAA was effective against several strains of influenza A virus, including the influenza strain A/Br, which is resistant to Tamiflu®. This is a key finding, as antiviral drug resistance is a growing problem in the clinic. For example, the pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza virus was initially susceptible to oseltamivir [37]; however, reports of clinical isolates resistant to oseltamivir have now emerged in several countries [38–40]. Our data suggest that DMXAA should be tested further as a novel antiviral agent for possible use in endemic and future emergency pandemic influenza situations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, R01 AI18797 (S.N.V.) and U19 AI083022 (D.L.F.), and Virion Systems, Inc., corporate funds (J.C.B.). This work was carried out in partial fulfillment of Ph.D. requirements (Q.M.N. and Z.J.R.). We thank Dr. Daniel Perez for providing the Tamiflu®-resistant influenza A/Brisbane/59/07 strain.

SEE CORRESPONDING EDITORIAL ON PAGE 327

- A/Br

- A/Brisbane/59/07 H1N1

- A/Wuhan

- A/Wuhan/359/95 H3N2

- CPE

- cytopathic effects

- DMXAA

- 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid

- HPRT

- hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyltransferase

- i.n.

- intranasal

- IRF-3

- IFN regulatory factor-3

- Log10

- decadic logarithm

- MDA-5

- melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5

- MDCK

- Madin-Darby canine kidney

- p.i.

- post-infection

- PR8

- A/PR/8/34

- qPCR

- quantitative real-time PCR

- RIG-I

- retinoic acid-inducible gene I

- TBK-1

- TRAF family member-associated NF-κB activator-binding kinase-1

- TCID50

- tissue culture infectious dose 50

AUTHORSHIP

K.A.S., Q.M.N., Z.J.R., J.C.B., and S.N.V. carried out the study design; K.A.S., Q.M.N., K.C.Y., Z.J.R., and J.R.T. performed experiments; J.R.T. and D.L.F. provided crucial reagents and guidance for in vivo studies; K.A.S., Q.M.N., J.C.B., and S.N.V. prepared the manuscript, with approval of all other coauthors.

REFERENCES

- 1. Thompson W. W., Shay D. K., Weintraub E., Brammer L., Cox N., Anderson L. J., Fukuda K. (2003) Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA 289, 179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thompson W. W., Shay D. K., Weintraub E., Brammer L., Bridges C. B., Cox N. J., Fukuda K. (2004) Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA 292, 1333–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moscona A. (2005) Neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 1363–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Oxford J. S., Bossuyt S., Balasingam S., Mann A., Novelli P., Lambkin R. (2003) Treatment of epidemic and pandemic influenza with neuraminidase and M2 proton channel inhibitors. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 9, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bright R. A., Medina M. J., Xu X., Perez-Oronoz G., Wallis T. R., Davis X. M., Povinelli L., Cox N. J., Klimov A. I. (2005) Incidence of adamantane resistance among influenza A (H3N2) viruses isolated worldwide from 1994 to 2005: a cause for concern. Lancet 366, 1175–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Democratis J., Pareek M., Stephenson I. (2006) Use of neuraminidase inhibitors to combat pandemic influenza. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58, 911–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moscona A. (2009) Global transmission of oseltamivir-resistant influenza. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 953–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ison M. G., Gubareva L. V., Atmar R. L., Treanor J., Hayden F. G. (2006) Recovery of drug-resistant influenza virus from immunocompromised patients: a case series. J. Infect. Dis. 193, 760–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Birnkrant D., Cox E. (2009) The Emergency Use Authorization of peramivir for treatment of 2009 H1N1 influenza. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 2204–2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Isaacs A., Lindenmann J. (1957) Virus interference. I. The interferon. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 147, 258–267 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Isaacs A., Lindenmann J., Valentine R. C. (1957) Virus interference. II. Some properties of interferon. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 147, 268–273 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keating G. M. (2009) Peginterferon-α-2a (40 kD): a review of its use in chronic hepatitis B. Drugs 69, 2633–2660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Foster G. R. (2010) Pegylated interferons for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: pharmacological and clinical differences between peginterferon-α-2a and peginterferon-α-2b. Drugs 70, 147–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Noseworthy J. H., Lucchinetti C., Rodriguez M., Weinshenker B. G. (2000) Multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 343, 938–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ascierto P. A., Kirkwood J. M. (2008) Adjuvant therapy of melanoma with interferon: lessons of the past decade. J. Transl. Med. 6, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Solov′ev V. D. (1969) The results of controlled observations on the prophylaxis of influenza with interferon. Bull. World Health Organ. 41, 683–688 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jordan W. S., Jr., Dowdle W. R., Easterday B. C., Ennis F. A., Gregg B. M., Kilbourne E. D., Seal J. A., Sloan F. A. (1974) Influenza research in the Soviet Union—1974. J. Infect. Dis. 130, 686–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Merigan T. C., Reed S. E., Hall T. S., Tyrrell D. A. (1973) Inhibition of respiratory virus infection by locally applied interferon. Lancet 1, 563–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Treanor J. J., Betts R. F., Erb S. M., Roth F. K., Dolin R. (1987) Intranasally administered interferon as prophylaxis against experimentally induced influenza A virus infection in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 156, 379–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Head M., Jameson M. B. (2010) The development of the tumor vascular-disrupting agent ASA404 (vadimezan, DMXAA): current status and future opportunities. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 19, 295–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Perera P. Y., Barber S. A., Ching L. M., Vogel S. N. (1994) Activation of LPS-inducible genes by the antitumor agent 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid in primary murine macrophages. Dissection of signaling pathways leading to gene induction and tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Immunol. 153, 4684–4693 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Roberts Z. J., Goutagny N., Perera P. Y., Kato H., Kumar H., Kawai T., Akira S., Savan R., van Echo D., Fitzgerald K. A., Young H. A., Ching L. M., Vogel S. N. (2007) The chemotherapeutic agent DMXAA potently and specifically activates the TBK1-IRF-3 signaling axis. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1559–1569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schafer S. L., Lin R., Moore P. A., Hiscott J., Pitha P. M. (1998) Regulation of type I interferon gene expression by interferon regulatory factor-3. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 2714–2720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McKeage M. J., Fong P., Jeffery M., Baguley B. C., Kestell P., Ravic M., Jameson M. B. (2006) 5,6-Dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid in the treatment of refractory tumors: a phase I safety study of a vascular disrupting agent. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 1776–1784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nhu Q. M., Shirey K., Teijaro J. R., Farber D. L., Netzel-Arnett S., Antalis T. M., Fasano A., Vogel S. N. (2010) Novel signaling interactions between proteinase-activated receptor 2 and Toll-like receptors in vitro and in vivo. Mucosal Immunol. 3, 29–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vogel S. N., Friedman R. M., Hogan M. M. (2001) Measurement of antiviral activity induced by interferons α, β, and γ. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. Chapter 6, Unit 6.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ottolini M. G., Blanco J. C., Eichelberger M. C., Porter D. D., Pletneva L., Richardson J. Y., Prince G. A. (2005) The cotton rat provides a useful small-animal model for the study of influenza virus pathogenesis. J. Gen. Virol. 86, 2823–2830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Teijaro J. R., Njau M. N., Verhoeven D., Chandran S., Nadler S. G., Hasday J., Farber D. L. (2009) Costimulation modulation uncouples protection from immunopathology in memory T cell responses to influenza virus. J. Immunol. 182, 6834–6843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vogel S. N., Fertsch D. (1987) Macrophages from endotoxin-hyporesponsive (Lpsd) C3H/HeJ mice are permissive for vesicular stomatitis virus because of reduced levels of endogenous interferon: possible mechanism for natural resistance to virus infection. J. Virol. 61, 812–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kawai T., Akira S. (2006) Innate immune recognition of viral infection. Nat. Immunol. 7, 131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Takaoka A., Wang Z., Choi M. K., Yanai H., Negishi H., Ban T., Lu Y., Miyagishi M., Kodama T., Honda K., Ohba Y., Taniguchi T. (2007) DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature 448, 501–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li J., Jameson M. B., Baguley B. C., Pili R., Baker S. D. (2008) Population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic model of the vascular-disrupting agent 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid in cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 2102–2110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tozer G. M., Kanthou C., Baguley B. C. (2005) Disrupting tumor blood vessels. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 423–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Falk L. A. (2001) Measurement of interferon-mediated antiviral activity of macrophages. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. Chapter 14, Unit 14.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hurt A. C., Ernest J., Deng Y. M., Iannello P., Besselaar T. G., Birch C., Buchy P., Chittaganpitch M., Chiu S. C., Dwyer D., et al. (2009) Emergence and spread of oseltamivir-resistant A(H1N1) influenza viruses in Oceania, South East Asia and South Africa. Antiviral Res. 83, 90–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hauge S. H., Dudman S., Borgen K., Lackenby A., Hungnes O. (2009) Oseltamivir-resistant influenza viruses A (H1N1), Norway, 2007–08. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15, 155–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2009) Update: drug susceptibility of swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) viruses, April 2009. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 58, 433–435 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Baz M., Abed Y., Papenburg J., Bouhy X., Hamelin M. E., Boivin G. (2009) Emergence of oseltamivir-resistant pandemic H1N1 virus during prophylaxis. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 2296–2297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen H., Cheung C. L., Tai H., Zhao P., Chan J. F., Cheng V. C., Chan K. H., Yuen K. Y. (2009) Oseltamivir-resistant influenza A pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus, Hong Kong, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15, 1970–1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Memoli M. J., Hrabal R. J., Hassantoufighi A., Eichelberger M. C., Taubenberger J. K. (2010) Rapid selection of oseltamivir- and peramivir-resistant pandemic H1N1 virus during therapy in 2 immunocompromised hosts. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50, 1252–1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]