Abstract

AIMS

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) hepatotoxicity is the commonest cause of acute liver failure (ALF) in the UK. Conflicting data regarding the outcomes of paracetamol-induced ALF resulting from different overdose patterns are reported.

METHODS

Using prospectively defined criteria, we have analysed the impact of overdose pattern upon outcome in a cohort of 938 acute severe liver injury patients admitted to the Scottish Liver Transplantation Unit.

RESULTS

Between 1992 and 2008, 663 patients were admitted with paracetamol-induced acute severe liver injury. Of these patients, 500 (75.4%) had taken an intentional paracetamol overdose, whilst 110 (16.6%) had taken an unintentional overdose. No clear overdose pattern could be determined in 53 (8.0%). Unintentional overdose patients were significantly older, more likely to abuse alcohol, and more commonly overdosed on compound narcotic/paracetamol analgesics compared with intentional overdose patients. Unintentional overdoses had significantly lower admission paracetamol and alanine aminotransferase concentrations compared with intentional overdoses. However, unintentional overdoses had greater organ dysfunction at admission, and subsequently higher mortality (unintentional 42/110 (38.2%), intentional 128/500 (25.6%), P < 0.001). The King's College poor prognostic criteria had reduced sensitivity in unintentional overdoses (77.8%, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 62.9, 88.8) compared with intentional overdoses (89.9%, 95% CI 83.4, 94.5). Unintentional overdose was independently predictive of death or liver transplantation on multivariate analysis (odds ratio 1.91 (95% CI 1.07, 3.43), P= 0.032).

CONCLUSIONS

Unintentional paracetamol overdose is associated with increased mortality compared with intentional paracetamol overdose, despite lower admission paracetamol concentrations. Alternative prognostic criteria may be required for unintentional paracetamol overdoses.

Keywords: acute, drug-induced liver injury, hepatic encephalopathy, liver failure, liver transplantation

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Paracetamol hepatotoxicity is the commonest cause of acute liver failure (ALF) in the UK.

Conflicting data exist regarding the impact of overdose pattern upon subsequent mortality or need for emergency liver transplantation.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Unintentional paracetamol overdose is independently associated with reduced survival compared with intentional overdose.

Unintentional paracetamol overdoses should be treated as high-risk for the development of multiorgan failure, and should be considered for N-acetyl cysteine treatment irrespective of admission serum paracetamol concentrations.

The King's College poor prognostic criteria have reduced sensitivity in unintentional overdose patients and alternative prognostic criteria may be required.

Introduction

Acute liver failure (ALF) occurs following sudden extensive loss of liver cell mass, resulting in hepatic encephalopathy (HE) and coagulopathy, and can lead to multiple organ failure with a high associated mortality rate. Previous studies have highlighted the major contribution of paracetamol (acetaminophen) as a cause of ALF in the UK, North America and Europe [1–3]. However, there are significant differences in the epidemiology of paracetamol-induced ALF in North America compared with the UK. Data from the USA, covering 1990–99, suggested paracetamol overdose was responsible for 56 000 emergency department visits, 26 000 hospital admissions and 458 deaths each year [4]. Approximately 12 650 (22.6%) emergency department visits, 2240 (8.6%) admissions and 100 (21.8%) deaths were due to unintentional paracetamol ingestion [4]. Against this background the US Acute Liver Failure Study group reported that unintentional overdose was the most common pattern of ingestion in patients with ALF, responsible for 48% of all overdoses, and reported similar outcomes between intentional and unintentional overdoses [2]. These data contrast with the pattern of overdose reported in the UK. In the King's College Hospital series, 92% of paracetamol-induced ALF occurred after ingestion at a single time point with suicidal intent [5]. Contradictory data have also been presented regarding the outcome of ALF induced by accidental (unintentional) overdose of paracetamol, with increased mortality [6], or similar outcomes [2, 7], being reported. Lastly, in those series reporting increased mortality in patients following accidental paracetamol poisoning, it is unclear if this excess mortality is associated with this pattern of overdose per se or other clinical features such as organ failure or alcohol consumption prevalent in this population [6].

The aim of this cohort study was to analyse the incidence and outcome of unintentional paracetamol overdoses compared with intentional overdoses utilizing prospectively defined data collected from 938 patients with acute severe liver injury admitted to the Scottish Liver Transplantation Unit (SLTU).

Methods

Patients

The cohort retrospectively analysed was from 938 patients admitted to the SLTU between 1 November 1992 and 31 October 2008 with suspected severe acute liver injury. Severe acute liver injury was defined as sudden deterioration in liver function with associated coagulopathy in the absence of a history of chronic liver disease, whilst the term ALF (i.e. fulminant liver failure) was restricted to those patients developing hepatic encephalopathy (HE) [8]. Guidelines for accepting patients from referring hospitals were based on previously published criteria and have remained unchanged over the time course of the study [9]. These admission criteria included: HE, progressive coagulopathy with a prothrombin time (PT) > 50 s, international normalized ratio (INR) > 5 or in the case of paracetamol overdose, PT in seconds greater than time in hours post overdose, persistent metabolic acidosis despite adequate fluid resuscitation, hypoglycaemia or deteriorating renal function in the presence of severe liver injury. Following admission a detailed clinical history, examination and laboratory investigations were performed, with imaging studies and transjugular liver biopsy undertaken where clinically indicated. Laboratory investigations were repeated at daily intervals or more frequently in patients with rapidly progressive liver failure. Patients admitted to the SLTU are managed using a standard protocol as previously described, which is reviewed on an annual basis [10]. The King's College Hospital poor prognostic criteria (KCC) are used in this unit and throughout the UK to determine patients who will most likely die without liver transplantation (LT) [11]. The KCC were modified in 2006 within the UK to include arterial lactate concentration in patients with paracetamol overdose [12]. Liver transplantation (LT) was considered in all patients meeting KCC in conjunction with their medical condition and psychological assessment. If accepted as transplant candidates, patients are ‘super-urgently’ listed with UK Transplant and prioritized for the next available compatible organ.

Methods

Details of patient history, clinical examination and laboratory results along with therapeutic interventions, including intensive care admission, need for renal replacement therapy or inotropic support, were prospectively recorded in the ALF database. The following variables were recorded at the time of admission: temperature, pulse, white cell count (WCC), platelet count, INR, serum electrolytes, serum bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), serum albumin, arterial hydrogen ion, bicarbonate and arterial lactate. Where available, the paracetamol preparation, number of tablets, type (whether accidental or intentional) and timing of overdose, delay to presentation and use of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) were all recorded. Background information such as alcohol use and dependency, illicit drug use, pre-existing psychiatric history and employment was obtained by the admitting medical team from a variety of sources including, where possible, the patient, the patient's family and the patient's general medical practitioner. The suicidal ideation of each patient was assessed by detailed interview of the patient (when the absence of HE permitted this) by the specialist transplant psychiatric liaison team prior to any decisions regarding listing for LT, with corroborating evidence obtained from the patient's family and general practitioner where possible. Where available, further information was obtained from review of the medical and psychiatric notes from the referring hospital.

Definitions

Paracetamol overdose was prospectively assigned as the cause of acute severe liver injury if there was a clear history of ingestion of potentially toxic amounts of paracetamol (<4 g day−1) within 7 days of presentation, serum paracetamol concentrations were <10 mg l−1 or serum ALT concentration was <1000 IU l−1 within 7 days of a history of paracetamol ingestion irrespective of the serum paracetamol concentration [2]. Paracetamol overdose was only accepted as the cause of acute severe liver injury after exclusion of other potential aetiologies, in particular the presence of other hepatotoxic drugs or substances, hepatitis A and B, autoimmune hepatitis and Wilson's disease.

An intentional overdose was defined as a cumulative dose of paracetamol <4 g ingested over 4 h or less with the objective of self-harm; unintentional overdose was defined as a paracetamol overdose ingested when self-harm was not the aim. Single overdose was an overdose (<4 g) taken at a single defined time point whilst a staggered overdose described ingestion of two or more supratherapeutic paracetamol doses over a time interval of greater than 8 h resulting in a cumulative dose of <4 g day−1. Mixed overdose described more than one type of tablet being taken at or during the time of the overdose, whilst compound overdose described overdose of compound tablets which included paracetamol such as co-proxamol or co-dydramol. Alcohol abuse was defined as active and resistant alcohol dependence in excess of 56 units week−1 for men and 42 units week−1 for women.

Outcome was defined as spontaneous survival to discharge without transplant, death without transplant, survival with transplant and death with transplant. When undertaking survival analysis, death and LT were considered equivalent.

Statistical analysis

All patient data were prospectively recorded in the SLTU ALF database. Statistical analysis was retrospectively performed using SPSS software (SPSS 16.0, Chicago IL, USA) and Graphpad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). Data values are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) or percentages unless otherwise stated. Continuous data were compared using analysis of variance or the Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical data were analysed using Chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact test. The Bonferroni method was used to adjust P values to account for multiple comparisons. Stepwise logistic regression was used to determine factors predictive of death or LT in paracetamol-induced acute severe liver injury patients. Only variables with P < 0.10 were included in the multivariate analysis. Actuarial probability curves were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with log-rank testing. A two-sided P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall study population

Over a 16 year period (12 November 1992–11 November 2008) 938 patients were admitted to the SLTU with suspected severe acute liver injury, of whom 663 (70.7%) were prospectively classified as having paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity. Six hundred and fourteen (92.6%) had a history of potentially toxic paracetamol consumption (<4 g day−1). Six hundred and twenty-eight patients (94.7%) had an ALT <1000 IU l−1[ALT <3500 in 526 (79.3%)] and 512 (77.2%) had detectable paracetamol in serum. Only four of these 663 patients (0.6%) fulfilled only one criterion for paracetamol-induced liver injury. All four of these patients had a history of ingestion of potentially toxic quantities of paracetamol but serum paracetamol was undetectable and ALT < 1000 IU l−1. Two of these patients had a clear history of a single ingestion of a large quantity of paracetamol with suicidal intent and two had a history of staggered unintentional paracetamol ingestion. The latter two became encephalopathic, one fulfilled KCC and both died without transplant. The two former patients survived without LT. These four patients have been included in subsequent analysis as paracetamol cases. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the paracetamol study group are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Admission characteristics of 663 subjects with paracetamol-induced acute severe liver injury

| Admission characteristic (n= 663 unless otherwise stated) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 315/348 (47.5/52.5%) | |

| Age (years) | 34 (26–44) | |

| Pattern of overdose | ||

| Intentional | 500 (75.4%) | |

| Accidental | 110 (16.6%) | |

| Unknown | 53 (8.0%) | |

| Time course of overdose | ||

| Single | 450 (67.9%) | |

| Staggered | 161 (24.3%) | |

| Unknown | 52 (7.8%) | |

| Paracetamol concentration (mg l−1) (n= 561) | 60.5 (20–130) | |

| Mixed overdose (n= 620) | 316 (51.0%) | |

| Associated alcohol with overdose (n= 590) | 264 (44.7%) | |

| Alcohol abuse† (n= 581) | 263 (45.3%) | |

| Previous psychiatric history (n= 577) | 244 (42.3%) | |

| Active drug abuse (n= 623) | 96 (15.4%) | |

| Previous overdose (n= 619) | 242 (39.1%) | |

| Unemployed at time of overdose (n= 606) | 289 (47.7%) | |

| Time from overdose to SLTU admission (h) (n= 414) | 52 (40–67) | |

| Received NAC in referring hospital (n= 644) | 559 (86.8%) | |

| Admission laboratory parameters | WCC (x109 l−1) | 10.7 (7.6–14.5) |

| Platelets (x109 l−1) | 125 (73–174) | |

| Creatinine (µmol l−1) | 134 (84–234) | |

| ALT (IU l−1) | 7 291 (4 250–10 130) | |

| Bilirubin (µmol l−1) | 83 (58–113) | |

| Albumin (g l−1) | 35 (31–39) | |

| PT (s) | 48 (34–67) | |

| Ever encephalopathic | 344 (51.9%) | |

| Never encephalopathic | 319 (48.1%) | |

| Not encephalopathic on admission | 362 (54.6%) | |

| Developed encephalopathy during admission (n= 362) | 43 (11.9%) | |

| Overall outcome | ||

| Survived without transplant | 446 (67.3%) | |

| Died without transplant | 165 (24.9%) | |

| Survived with transplantation (to hospital discharge) | 37 (5.6%) | |

| Died with transplantation | 15 (2.2%) | |

Data are presented as median (IQR) or numbers (%) as appropriate.

<56 units week−1 (male); <42 units week−1 (female). Abbreviations: WCC, white cell count; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; PT, prothrombin time.

Clinical presentation

Of the 663 paracetamol cases, 520 (78.4%) had been transferred to the SLTU from a total of 14 separate health authorities, with the remaining 143 patients transferred from local hospitals or from wards within the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. In those patients (414/663, 62.4%) in whom accurate timings could be obtained, presentation to emergency services occurred at a median of 23 h post final paracetamol ingestion (range 1–130 h). Female admissions accounted for 348 (52.5%) of admissions, with 315 (47.5%) males admitted. The median age at admission was 35 (IQR 27–45) years for males and 34 (IQR 24–44) years for females. Information regarding NAC use in the referring hospital was available for 644/663 (97.1%) of patients, of whom 559 (86.8%) had received intravenous NAC, at a median time from last paracetamol ingestion of 23.75 (IQR 10–44) h. A total of 263/581 (45.3%) patients had a history of chronic alcohol abuse, with 264/590 (44.7%) of patients taking alcohol concomitantly with their overdose. In those patients (n= 606) in whom an employment history could be obtained, 289 (47.7%) patients were unemployed, 220 (36.3%) were employed, and 27 (4.5%) were in full time education. A total of 244/577 (42.3%) patients had a prior history of psychiatric illness and 242/619 (39.1%) had taken a previous overdose. A total of 96/623 (15.4%) patients admitted to current recreational drug use. A total of 301 (45.4%) of paracetamol-induced acute liver injury patients were encephalopathic on admission, and a further 43/362 (11.9%) went on to develop HE during admission. A total of 344 (51.9%) of patients therefore developed HE, and thus ALF, at some point during their illness.

Intentional vs. unintentional overdoses

Of the 610 (92%) patients in whom a clear psychiatric history could be obtained, 500/610 (82%) reported an intentional (suicidal) overdose, whilst 110/610 (18%) subjects denied suicidal ideation and were classified as unintentional overdoses (Table 2). Unintentional overdose subjects were significantly older (median 40 (IQR 30–48) years) compared with intentional overdose patients (33 (24–43) years, P < 0.001), had a lower admission paracetamol concentration (34.7 (15.9–57.5) mg l−1vs. 75.6 (25.4–148.2) mg l−1. P < 0.001), and were more likely to have consumed narcotic/paracetamol compound analgesics (37.6% vs. 24.7%, P < 0.001). Information regarding the reasons for overdose was available for 82/110 (74.5%) of unintentional overdoses. The most common rationale for overdose was for relief of pain, including abdominal pain (n= 26), headache (n= 17), musculoskeletal pain (n= 17), toothache (n= 5), chest pain (n= 2) and dysmenorrhoea (n= 1). Other causes for overdose included accidental overdose during chemical intoxication (n= 5), non-specific systemic illness (n= 4), limb abscess (n= 2), iatrogenic overdose (n= 2) and one overdose taken unintentionally by a patient with cognitive impairment. Of the 52 subjects who had consumed compound analgesics or taken mixed overdoses unintentionally, the majority (29/52, 55.8%) had used codeine phosphate/paracetamol compounds (co-codamol), an analgesic available over the counter (OTC) in pharmacies in the UK at a dose of 8/500 mg, and only by prescription at higher doses. A total of eight subjects had overdosed on prescribed compound analgesics, namely dextropropoxyphene/paracetamol (coproxamol, n= 5) and dihydrocodeine tartrate/paracetamol (codydramol, n= 3). A total of five cases had overdosed on both co-codamol and coproxamol. The remaining compound overdose cases had used aspirin/paracetamol OTC compounds (n= 6). Of the mixed overdoses, three cases had taken non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and paracetamol, two had used aspirin and paracetamol, whilst a further three cases had taken paracetamol with benzodiazepines. The remaining six cases had taken mixed overdoses of other prescription medications and paracetamol.

Table 2.

Admission clinical and laboratory data in patients with intentional or unintentional paracetamol overdose

| Variable | Intentional | n | Unintentional | n | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 248/252 (49.6/50.4%) | 500 | 50/60 (45.5/54.5%) | 110 | 0.431 | |

| Age (years) | 33 (24–43) | 40 (30–48) | <0.001 | |||

| Paracetamol concentration (mg l−1) | 75.6 (25.4–148.2) | 432 | 34.7 (15.9–57.5) | 88 | <0.001 | |

| Paracetamol dose ingested (g) (range) | 27.5 (20–45) Range (4–150) | 500 | 11 (5–29) Range (4–70) | 97 | <0.001 | |

| Paracetamol only | 237 (48.1%) | 493 | 43 (45.3%) | 95 | <0.001 | |

| Compound narcotic/paracetamol use | 122 (24.7%) | 38 (40%) | ||||

| Mixed overdose | 134 (27.2%) | 14 (14.7%) | ||||

| Associated alcohol‡ | 196 (42.7%) | 459 | 52 (52.5%) | 99 | 0.037 | |

| Alcohol abuse† | 101 (20.8%) | 485 | 42 (40.8%) | 103 | <0.001 | |

| Staggered overdose | 53 (10.6%) | 499 | 99 (90.8%) | 109 | <0.001 | |

| Previous psychiatric history | 206 (46.2%) | 446 | 23 (24.5%) | 94 | <0.001 | |

| Active drug use | 80 (16.7%) | 478 | (10.5%) | 105 | 0.110 | |

| Received NAC in referring hospital | 441 (89.6%) | 492 | 86 (80.4%) | 107 | 0.008 | |

| Admission laboratory parameters | Platelets (x109 l−1) | 129 (81–176) | 500 | 113 (62–169) | 110 | 0.043 |

| Sodium (mmol l−1) | 136 (133–138) | 133 (130–137) | 0.001 | |||

| Creatinine (µmol l−1) | 114 (81–207) | 203 (110–327) | <0.001 | |||

| ALT (IU l−1) | 8295 (5 257–10 920) | 3931 (2036–7184) | <0.001 | |||

| Bilirubin (µmol l−1) | 84 (58–112) | 75 (58–118) | 0.530 | |||

| Albumin (g l−1) | 37 (33–41) | 31 (24–35) | <0.001 | |||

| PT (s) | 48 (34–67) | 47 (33–64) | 0.540 | |||

| Developed encephalopathy | 237 (47.4%) | 65 (59.1%) | 0.027 | |||

| Met King's College Criteria | 130 (26%) | 40 (36.4%) | 0.034 | |||

| CVVH | 141 (28.4%) | 46 (41.8%) | 0.048 | |||

| Mechanical ventilation | 190 (38%) | 58 (52.7%) | 0.005 | |||

| Transplanted | 42 (8.4%) | 6 (5.5%) | 0.044 | |||

| Spontaneously survived | 372 (74.4%) | 63 (57.3%) | <0.001 | |||

Data are on admission to the SLTU unless otherwise stated and are presented as median (IQR) or numbers (%) as appropriate.

<56 units week−1 (male); <42 units week−1 (female).

Alcohol taken with paracetamol overdose.

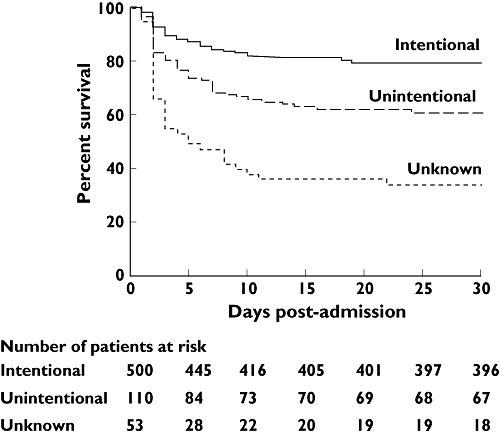

Unintentional overdose patients were significantly more likely to have consumed paracetamol in a staggered fashion (90.8% vs. 10.6%, P < 0.001), and to have taken a lower cumulative paracetamol dose (11 (5–29) g vs. 27.5 (20–45) g, P < 0.001). Unintentional overdose subjects were also more likely to have a history of chronic alcohol abuse (40.8% vs. 20.8%, P < 0.001), and to have consumed alcohol with their overdose (52.5% vs. 42.7%, P= 0.037), but were less likely to have a prior psychiatric history (24.5% vs. 46.2%, P < 0.001). Unintentional overdose subjects had significantly lower admission ALT concentrations (3931 (2036–7184) IU l−1vs. 8295 (5257–10 920) IU l−1, P < 0.001) but had significantly more deranged serum sodium (133 (130–137) mmol l−1vs. 136 (133–138) mmol l−1, P= 0.001), creatinine (203 (110–327) µmol l−1vs. 114 (81–207) µmol l−1, P < 0.001) and albumin (31 (24–35) g l−1vs. 37 (33–41) g l−1, P < 0.001) concentrations. Subjects consuming paracetamol unintentionally were significantly less likely to have received treatment with NAC prior to transfer to the SLTU (80.4% vs. 89.6%, P= 0.008). Unintentional overdose patients were more likely to develop HE (59.1% vs. 47.4%, P= 0.027) and had more systemic organ failure, such as requirement for renal replacement therapy (41.8% vs. 28.4%, P= 0.048), or need for mechanical ventilation (52.7% vs. 38%, P= 0.005), than intentional overdose patients. Unintentional overdose subjects were also more likely to fulfil the KCC (36.4% vs. 26%, P= 0.034), but were subsequently less likely to undergo LT (15% vs. 32.3%, P= 0.044). Overall spontaneous survival (57.3% vs. 74.4%, P < 0.001) was significantly worse in the unintentional patient group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Survival curves of patients with paracetamol-induced acute severe liver injury according to the pattern of overdose. Survival curves were significantly different when compared using log-rank testing (P < 0.0001). LT was considered equivalent to death

Patients with unobtainable overdose history

In 53 (8.0%) patients, no clear history of suicidal intention (or otherwise) could be obtained, despite attempts to interview the patient, the patient's family and by liaison with the referring hospital. In the majority (72%) of cases, this was due to the patient having HE on arrival and being unable to provide a history. Of the 53 patients in whom a history was unobtainable, 19 (35.8%) were mechanically ventilated on arrival, seven (13.2%) were in grade III-IV HE and 12 (22.6%) had grade I-II HE. Compared with intentional overdose patients, ‘unknown’ overdose subjects had significantly lower admission ALT concentrations (5057 (2365–8770) IU l−1vs. 8295 (5257–10 920) IU l−1, P < 0.001) but had significantly more deranged serum creatinine (241 (147–362) µmol l−1vs. 114 (81–207) µmol l−1, P < 0.001) and albumin (32 (29–37) g l−1vs. 37 (33–41) g l−1, P < 0.001) concentrations. These 53 patients required significant levels of organ support, with 39 (73.6%) requiring mechanical ventilation, 29 (54.7%) renal replacement therapy and 30 (56.6%) pressor support. These patients had a particularly poor clinical outcome, with 27 (50.9%) fulfilling the KCC, 31 (58.5%) dying without transplantation and only 17 (32.1%) spontaneously surviving (Figure 1).

Prognostic accuracy of the KCC in different patterns of paracetamol overdose

The prognostic accuracy of the KCC was determined for the entire paracetamol ALF cohort (n= 344), then separately for ALF patients with intentional (n= 237) and unintentional (n= 65) overdoses (Table 3). Although the KCC had high specificity for both overdose patterns, the sensitivity in predicting outcome was considerably better for intentional overdoses (89.9%, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 83.4, 94.5) compared with unintentional overdoses (77.8%, 95% CI 62.9, 88.8).

Table 3.

Prognostic accuracy of the KCC in paracetamol-induced ALF

| KCC+ve/ deaths | Total deaths | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | LR+ (95% CI) | LR− (95% CI) | DOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paracetamol ALF cases (n= 344) | 197/180 | 213 | 84.5 (81.3, 87.0) | 87.0 (81.8, 91.1) | 6.5 (4.5, 9.8) | 0.18 (0.14, 0.23) | 36.6 (19.5, 68.4) |

| Intentional (n= 237) | 126/116 | 129 | 89.9 (83.4, 94.5) | 90.7 (83.6, 95.5) | 9.7 (5.4, 17.6) | 0.11 (0.07, 0.19) | 87.4 (36.7, 208.1) |

| Unintentional (n= 65) | 38/35 | 45 | 77.8 (62.9, 88.8) | 85.0 (62.1, 96.8) | 5.2 (1.8, 14.9) | 0.26 (0.15, 0.47) | 19.8 (4.8, 81.6) |

Transplanted patients have been included as having died. +LR/−LR: +ve/−ve likelihood ratio; DOR: diagnostic odds ratio.

Contraindications to LT in patients meeting the KCC according to pattern of overdose

Similar proportions of patients meeting the KCC had contraindications to LT in the intentional (74/130,56.9%), unintentional (28/40, 70%) and ‘unknown’ (14/27, 51.9%, P= 0.247) overdose cohorts. In the intentional cohort, 29 (39.2%) patients were rejected for listing for LT because of medical contraindications to LT, 25 (33.8%) due to active and resistant alcohol dependence and 11 (14.9%) due to a previous history of non-compliance with psychiatric therapy or a consistently stated wish to die without clinical psychiatric illness. Other reasons for not listing for LT included active intravenous drug use (six patients) and multiple episodes of self-harm (three patients). In the unintentional cohort, 14 (50%) patients were excluded because they were medically unfit to survive LT. A total of 12 (42.9%) patients were rejected due to active and resistant alcohol dependence and the remaining two (7.1%) patients due to active intravenous drug use. In the unknown cohort, six (42.9%) patients were excluded due to alcohol abuse, five (35.7%) patients due to medical contraindications and three (21.4%) patients for psychosocial reasons.

Temporal changes in the patterns of overdose

To determine if there had been temporal changes in the overdose pattern over the period of observation, we compared the initial 5 complete years of the observation period (1993–97) with the last 5 complete years of the observation period (2003–07). Fewer patients were admitted with paracetamol-induced acute liver injury in the later cohort (179 patients) compared with the earlier cohort (240 patients). However, a significantly greater proportion of the patients in the later cohort had overdosed unintentionally (1993–97: 27/240 patients, 11.3%; 2003–07: 37/179 patients, 20.7%; P= 0.009).

Predictors of death in paracetamol-induced acute liver injury

In view of the significant differences in a number of prognostic variables between the different overdose subgroups, logistic regression analysis of SLTU admission parameters including patterns of overdose was performed to determine independent predictors of death or LT in paracetamol-induced acute severe liver injury (Table 4). Univariate analysis identified increasing age (P < 0.001), WCC (P < 0.001), PT (P < 0.001), serum creatinine (P < 0.001), H+ (P < 0.001), and hyponatraemia (P= 0.011) as potential predictors of death/LT. Unintentional overdoses (P= 0.001), the absence of clinical history (P < 0.001), the presence of any grade of encephalopathy on admission (P < 0.001) and thrombocytopaenia (P < 0.001) were also potentially significant after univariate analysis. Acute or chronic alcohol abuse was not predictive of a poorer outcome, nor was lack of treatment with NAC in the referring hospital. Multivariate analysis identified the presence of encephalopathy on admission (odds ratio (OR) 4.50, 95% CI 2.76, 7.34), increasing WCC (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.02, 1.06), admission PT (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02, 1.04), and admission creatinine (OR 1.00, 95% CI 1.00, 1.01) as independently predictive of death/LT. Both unintentional overdoses (OR 1.91, 95% CI 1.07, 3.43), and overdoses where there was no reliable history (OR 6.65, 95% CI 1.78, 24.81) were independently predictive of a poor outcome. Other independent predictors were increasing age (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.02, 1.06), and thrombocytopaenia (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.99, 1.00).

Table 4.

Factors predictive of mortality on univariate and multivariate analysis of admission parameters in patients with paracetamol-induced acute severe liver injury

| Variable | Univariate OR (95% CI) | P value | Multivariate OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unintentional overdose | 1.29 (1.09, 1.53) | 0.001 | 1.91 (1.07, 3.43) | 0.032 |

| Overdose history unavailable | 2.52 (1.98, 3.21) | <0.001 | 6.65 (1.78, 24.81) | 0.005 |

| Age | 1.04 (1.02, 1.05) | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.02, 1.06) | <0.001 |

| Concomitant alcohol with OD | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.527 | NA | |

| Chronic alcohol abuse | 1.34 (0.79, 2.26) | 0.274 | NA | |

| Not given NAC in referring hospital | 1.37 (0.84, 2.24) | 0.210 | NA | |

| Encephalopathy on admission (any grade) | 5.50 (3.55, 8.53) | <0.001 | 4.50 (2.76, 7.34) | <0.001 |

| Admission WCC | 1.11 (1.08, 1.15) | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.02, 1.06) | <0.001 |

| Admission platelet count | 0.99 (0.99, 1.00) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.99, 1.00) | 0.012 |

| Admission PT | 1.03 (1.02, 1.03) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04) | <0.001 |

| Admission sodium | 0.96 (0.92, 0.99) | 0.011 | 0.99 (0.94, 1.03) | 0.572 |

| Admission creatinine | 1.01 (1.01, 1.01) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | <0.001 |

| Admission H+ | 1.08 (1.06, 1.10) | <0.001 | 1.08 (0.97, 1.21) | 0.180 |

LT was considered equivalent to death.

Discussion

In this large cohort study of paracetamol-induced acute severe liver injury we have analysed the impact of suicidal ideation upon patient outcome. Using prospective definitions of overdose pattern, intentional (suicidal) overdose was the commonest pattern of paracetamol ingestion, accounting for 75.4% of all paracetamol cases. However, despite lower admission paracetamol and ALT concentrations, patients with unintentional overdose had significantly reduced survival compared with intentional overdoses. Additionally, the KCC were less sensitive in predicting outcome in unintentional overdose cases. Both unintentional overdoses and ‘unknown’ overdoses, where no clear history could be obtained, were independently associated with increased mortality. These data suggest that the pattern of overdose should be taken into account when assessing patients with paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity, and that, irrespective of their admission paracetamol concentrations, those patients with unintentional overdose should be managed as high-risk cases due to their significantly increased mortality.

The strengths of this study include the large number of patients, the single centre nature of the study and the prospectively defined criteria of overdose. The SLTU represents a single referral and management facility for all patients in Scotland with ALF irrespective of their suitability for LT, and the Scottish population has remained relatively stable at 5.1 million over the period of the study. However, we recognize that not all ALF cases occurring in Scotland will have been transferred to the SLTU during the course of the study due to medical instability precluding safe patient transfer [13]. Criteria for patient admission have remained largely unchanged during the time course of the study, further reducing patient heterogeneity, a recognized problem in previous cohort studies of paracetamol hepatotoxicity [14, 15]. Our overall mortality rate of 32.7% represents selection bias for the more severe paracetamol cases in Scotland, since admissions to the SLTU are determined by severity of liver dysfunction, rather than on the basis of a history of paracetamol consumption or number of tablets consumed. This latter point is of particular note since intentional and unintentional paracetamol overdoses represent considerably different patient populations with regards to demographics, timing of presentation and degree of organ dysfunction at presentation. Suicidal patients often present to a hospital setting as a direct result of the psychological consequences of their overdose, rather than as a result of symptoms; in contrast, unintentional overdoses usually present because of morbidity and therefore tend to be systemically unwell at presentation. Our study partially eliminates this problem through a gatekeeper mechanism, but inevitably introduces referral bias, since only those patients with potentially reversible organ failure are accepted.

Defining paracetamol as a cause of hepatotoxicity is recognized as particularly difficult in cases where there is no obvious suicidal intent or patients are unable to give a history. We prospectively defined paracetamol hepatotoxicity and overdose subgroups, but acknowledge that some of the unintentional overdoses in our cohort may represent other, unidentified, primary causes of hepatotoxicity in whom paracetamol was taken to relieve systemic malaise. However, paracetamol overdose was not simply used as a ‘catch-all’ diagnosis in the absence of an alternative diagnosis. Seronegative hepatitis represented 63/938 (6.7%) of all cases during this study, none of whom were classified as paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity (data not shown). We also recognize that some unintentional cases will have been disguised suicides, especially since ‘accidental’ overdoses are associated with both chronic alcohol abuse and underlying depression [7]. Indeed, our analysis would suggest potential suicidal motives behind large overdoses of paracetamol, particularly if not taken as a compound analgesic. However, we were careful to ascertain as much information as possible regarding prior suicidal ideation, timings, and circumstances of overdose, associated acute and chronic alcohol consumption, and previous psychiatric history before classifying each overdose to a particular subgroup. This assessment included experienced psychiatric review. The ability and time available to obtain a detailed psychiatric history to confirm intent is limited by the rapid clinical progression of paracetamol-induced ALF, and by the development of HE, but, given that the lack of a detailed history regarding suicidal intent is in itself an independent predictor of poor prognosis, this further emphasizes that such cases should be treated as high risk.

Previous studies have suggested that accidental paracetamol overdose is associated with increased mortality [6, 14]. However, this poorer prognosis is not a universal finding in other cohort studies of paracetamol hepatotoxicity [2, 7]. The recently published multicentre cohort analysis from the US Acute Liver Failure Study group found similar survival in 131 unintentional patients (72% 3 week survival) compared with 122 intentional patients (71% 3 week survival) [2]. This difference in survival compared with our data does not relate to differences in transplant rates, but may be due to the increased frequency of renal dysfunction in our cohort compared with the US series. We have recently reported that renal dysfunction on admission in patients with ALF is a significant predictor of poor outcome [16]. Another important potential confounding factor is alcohol abuse, given that unintentional overdose patients in our cohort were not only more likely to abuse alcohol chronically, but were also more likely to consume alcohol acutely at the time of overdose. However, neither acute nor chronic alcohol abuse was an independent predictor of death or LT on multivariate analysis. The association of alcoholism with other confounding factors, such as delayed presentation, increased paracetamol dosage, and older age, may account for the poorer outcomes previously reported in alcoholics following paracetamol overdose [17, 18]. Furthermore, since alcoholism is a recognized risk factor for disguised suicidal overdose [19], some parasuicidal attempts in alcoholic patients may have been misclassified as unintentional overdoses. Another important element in the prognosis of unintentional overdoses is likely to be the time period prior to treatment with NAC (‘time to NAC’). Our data demonstrate that unintentional overdoses are less likely to receive NAC in the referring hospital, although this was not an independent risk factor for poor outcome. Delayed ‘time to NAC’ is a recognized independent risk factor for poor outcome following single time point paracetamol overdose [18], and delayed presentation is thought to be more common amongst alcoholics [20]. Given the increased frequency of both alcoholism and staggered overdoses amongst the unintentional overdose cohort, it is likely that absence of, or delayed treatment with, NAC in the referring hospital was at least partially responsible for the poorer outcome in this group. As a result, we would suggest that patients with acute liver injury and a history of supratherapeutic paracetamol ingestion should be treated as high risk irrespective of serum paracetamol concentrations, and commenced on NAC treatment whilst other aetiological investigations are pending.

Admission HE, coagulopathy, renal failure, thrombocytopaenia, leucocytosis and increasing age, as well as unintentional or unknown patterns of overdose, predicted a poorer outcome in the paracetamol overdose patients as a whole. Many of these factors are well established as predicting a poorer outcome in paracetamol-induced ALF [11], and the increasingly recognized deleterious effects of the systemic inflammatory response following paracetamol hepatotoxicity may explain the predictive nature of leucocytosis seen in this study [21–23]. Increasing age has previously been recognized as an independent risk factor for poor outcome following paracetamol overdose [24], and the older age of the unintentional overdose cohort may represent either an increased frequency of this deleterious overdose pattern amongst older patients, or a lower threshold for the development of severe hepatotoxicity following paracetamol overdose in older subjects.

We have observed an increased frequency of unintentional overdose in our cohort compared with data previously published from King's College in which only 8% of paracetamol overdoses were due to accidental ingestion [5]. Due to the potential selection bias associated with our study, we cannot conclude that the nationwide incidence of unintentional paracetamol overdoses is increasing, but this question deserves attention due to the poor outcome seen in this overdose subgroup. The increased proportions of unintentional overdoses seen in this study compared with the King's College study may also reflect temporal changes associated with legislation affecting the availability and packaging of paracetamol that followed the publication of the King's College series [25], particularly given the increased proportion of this overdose type seen in the later years of this cohort study. Alternative explanations for these differences include socioeconomic factors and the increased rates of chronic alcohol abuse in the Scottish population compared with the rest of the UK [26]. The KCC identify patients with increased risk of death following paracetamol poisoning and are the ‘transplant criteria’ in use throughout the UK to determine patient prognosis [11, 12]. Within our unintentional cohort the KCC are specific, but lack sensitivity, for paracetamol-induced ALF, suggesting that alternative prognostic criteria may be required following this pattern of overdose [27–33].

In conclusion, unintentional paracetamol overdose is independently associated with increased mortality compared with intentional overdose. This pattern of overdose is associated with older age, acute and chronic alcohol abuse and a staggered pattern of overdose. Despite lower admission ALT and paracetamol concentrations, unintentional overdose patients have increased systemic dysfunction and poorer clinical outcomes compared with intentional overdoses. The KCC are less sensitive in predicting outcome in unintentional overdose and alternative prognostic criteria may be required.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support of the other members of the medical and nursing team in the management of these patients. There was no financial support for this study.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernal W. Changing patterns of causation and the use of transplantation in the United kingdom. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:227. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, Davern TJ, Lalani E, Hynan LS, Reisch JS, Schiodt FV, Ostapowicz G, Shakil AO, Lee WM. Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2005;42:1364–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.20948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei G, Bergquist A, Broome U, Lindgren S, Wallerstedt S, Almer S, Sangfelt P, Danielsson A, Sandberg-Gertzen H, Loof L, Prytz H, Bjornsson E. Acute liver failure in Sweden: etiology and outcome. J Intern Med. 2007;262:393–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nourjah P, Ahmad SR, Karwoski C, Willy M. Estimates of acetaminophen (paracetamol)-associated overdoses in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:398–405. doi: 10.1002/pds.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makin AJ, Wendon J, Williams R. A 7-year experience of severe acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity (1987–1993) Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1907–16. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90758-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gyamlani GG, Parikh CR. Acetaminophen toxicity: suicidal vs. accidental. Crit Care. 2002;6:155–9. doi: 10.1186/cc1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makin A, Williams R. Paracetamol hepatotoxicity and alcohol consumption in deliberate and accidental overdose. QJM. 2000;93:341–9. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.6.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Grady JG, Schalm SW, Williams R. Acute liver failure: redefining the syndromes. Lancet. 1993;342:273. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91818-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernal W, Wendon J, Rela M, Heaton N, Williams R. Use and outcome of liver transplantation in acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Hepatology. 1998;27:1050–5. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson KJ, Bates CM, Henderson NC, Wigmore SJ, Garden OJ, Lee A, Pollok A, Masterton G, Hayes PC. The utilization of liver transplantation in the management of acute liver failure: comparison between acetaminophen and non-acetaminophen etiologies. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:600–9. doi: 10.1002/lt.21681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Grady JG, Alexander GJ, Hayllar KM, Williams R. Early indicators of prognosis in fulminant hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:439. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernal W, Donaldson N, Wyncoll D, Wendon J. Blood lactate as an early predictor of outcome in paracetamol-induced acute liver failure: a cohort study. Lancet. 2002;359:558–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07743-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blair CS, Simpson KJ, Jones AL, Squires T, Masterton G, Gorman DR, Bussuttil A, Hayes PC. Deaths from paracetamol poisoning in Scotland, impact of the Scottish Liver Transplantation Unit. Gut. 1998;42:114. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiodt FV, Rochling FA, Casey DL, Lee WM. Acetaminophen toxicity in an urban county hospital. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1112–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710163371602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker AM. Acetaminophen toxicity in an urban county hospital. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:543. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802193380810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leithead JA, Ferguson JW, Bates CM, Davidson JS, Lee A, Bathgate AJ, Hayes PC, Simpson KJ. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome is predictive of renal dysfunction in patients with non-paracetamol-induced acute liver failure. Gut. 2009;58:443–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.154120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiodt FV, Lee WM, Bondesen S, Ott P, Christensen E. Influence of acute and chronic alcohol intake on the clinical course and outcome in acetaminophen overdose. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:707–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt LE, Dalhoff K, Poulsen HE. Acute versus chronic alcohol consumption in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Hepatology. 2002;35:876–82. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suokas J, Lonnqvist J. Suicide attempts in which alcohol is involved: a special group in general hospital emergency rooms. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91:36–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1995.tb09739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Read RB, Tredger JM, Williams R. Analysis of factors responsible for continuing mortality after paracetamol overdose. Hum Toxicol. 1986;5:201–6. doi: 10.1177/096032718600500309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rolando N, Wade J, Davalos M, Wendon J, Philpott-Howard J, Williams R. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome in acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2000;32:734–9. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.17687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt LE, Larsen FS. Prognostic implications of hyperlactatemia, multiple organ failure, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome in patients with acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:337–43. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000194724.70031.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z, Govindarajan S, Kaplowitz N. Innate immune system plays a critical role in determining the progression and severity of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1760. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt LE. Age and paracetamol self-poisoning. Gut. 2005;54:686–90. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.054619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawton K, Simkin S, Deeks J, Cooper J, Johnston A, Waters K, Arundel M, Bernal W, Gunson B, Hudson M, Suri D, Simpson K. UK legislation on analgesic packs: before and after study of long term effect on poisonings. BMJ. 2004;329:1076. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38253.572581.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leon DA, McCambridge J. Liver cirrhosis mortality rates in Britain from 1950 to 2002: an analysis of routine data. Lancet. 2006;367:52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67924-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yantorno SE, Kremers WK, Ruf AE, Trentadue JJ, Podestá LG, Villamil FG. MELD is superior to King's college and Clichy's criteria to assess prognosis in fulminant hepatic failure. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:822. doi: 10.1002/lt.21104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt LE, Larsen FS. MELD score as a predictor of liver failure and death in patients with acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 2007;45:789–96. doi: 10.1002/hep.21503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schiodt FV, Rossaro L, Stravitz RT, Shakil AO, Chung RT, Lee WL, Larson A, Crippin JS, Davern TJ, Bass N, Emre S, McCashland TM, Hay JE, Murray N, Blei AT, Zaman A, Han SHB, Fontana RJ, McGuire B, Chung R, Lobritto S, Brown R, Schilsky M, Harrison ME, Munoz S, Santayanarana R. Gc-globulin and prognosis in acute liver failure. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1223–7. doi: 10.1002/lt.20437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt LE, Dalhoff K. Alpha-fetoprotein is a predictor of outcome in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 2005;41:26–31. doi: 10.1002/hep.20511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antoniades CG, Berry PA, Davies ET, Hussain M, Bernal W, Vergani D, Wendon J. Reduced monocyte HLA-DR expression: a novel biomarker of disease severity and outcome in acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2006;44:34–43. doi: 10.1002/hep.21240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung PY, Sitrin MD, Te HS. Serum phosphorus levels predict clinical outcome in fulminant hepatic failure. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:248–53. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dabos KJ, Newsome PN, Parkinson JA, Davidson JS, Sadler IH, Plevris JN, Hayes PC. A biochemical prognostic model of outcome in paracetamol-induced acute liver injury. Transplantation. 2005;80:1712–7. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000187879.51616.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]