Abstract

Acute Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection is associated with central and peripheral neurological complications such as meningitis, encephalitis, myelitis and radiculopathy in 0.5-7.5% of patients (1). The peripheral nervous system manifestations of acute EBV infection include mononeuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex, autonomic neuropathy, and polyradiculopathy (2). Brachial plexopathy in children and immunocompromised adults with acute EBV infection has been described, likely as a dysimmune neuropathy triggered by the EBV (3, 4). We present a case of brachial plexopathy complicating prior EBV infection in a healthy adult.

Key words: EBV, amyotrophy, demyelinating

Case report

A previously healthy, 26-year-old female presented with a three-month history of slowly progressive weakness and wasting of her left hand muscles. Two-three weeks prior to the onset of the weakness, she had a severe flu-like illness lasting for seven days with full recovery. She did not have shoulder, scapular or neck pain. The patient noted numbness in the tips of her fingers, but no other sensory symptoms. She did not have bulbar or constitutional symptoms. Her symptoms had progressed for 3 months and then stabilized during the 3 months before initial assessment. Examination showed normal cranial nerves; specifically, Horner’s syndrome was not present. She had severe atrophy of the left intrinsic and hypothenar muscles and mild atrophy of the thenar muscles. Power in left hand muscles was reduced: finger extensors grade 4, intrinsic hand muscles grade 2 (in keeping with atrophy), thenar muscles grade 3- (not proportional to the atrophy) on the MRC scale. All other muscle groups were normal. Pinprick sensation was reduced over the palmar aspect of the left fourth and fifth digits. The neurological examination, including deep tendon reflexes, was otherwise normal.

Nerve conduction studies were abnormal in the left arm with low amplitudes of the evoked motor responses, more evident with proximal stimulation with possible multilevel conduction blocks of the left ulnar nerve, across Erb’s point, in the axilla and in the forearm. The median and ulnar nerve F wave responses were absent. Distal motor latencies were prolonged. Sensory nerve conduction studies demonstrated low amplitude of the ulnar sensory nerve action and slowing of the ulnar sensory nerve conduction velocity. Median sensory nerve conduction studies were normal. Nerve conduction studies in the right arm were normal. The left medial antebrachial sensory nerve conduction study was normal as well (Table 1). Electromyography showed reduced recruitment in the extensor digitorum communis, abductor pollicis brevis (APB) and first dorsal interosseus (FDI) muscles. Chronic neurogenic type motor units with increased amplitudes, prolonged durations and polyphasic morphology were present in the left FDI and APB muscles. Fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves were noted in the left FDI (1+), but not in other muscles. More proximal muscles of the left arm were normal. These studies indicated the presence of a left brachial plexopathy with primarily demyelinating features given the lack of frequent abnormal spontaneous activity on electromyography, the discrepancy between atrophy and strength on clinical examination, the prolongation of distal motor latencies, the reduced conduction velocities, the loss of F waves and the conduction block. Imaging of the brachial plexus was done to exclude a compressive lesion such as thoracic outlet syndrome although the nerve conduction studies showed a multilevel process of the ulnar nerve in the extremity and distal median nerve impairment.

Table 1. Neurophysiological findings.

| Motor Nerve Conduction Studies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerve-Muscle | Stimulation site | Onset latency, ms | F-wave | Amplitude Motor (mV) | Conduction velocity (m/s) |

| Left Median- Abductor Pollicis Brevis | Erb's | 13.8 | NR | 5.1 | 66 |

| Axilla | 9.5 | 5.1 | 57 | ||

| Elbow | 8.1 | 5.4 | 51 | ||

| Wrist | 3.9 | 5.8 | |||

| Left Ulnar- Abductor Digiti Quinti | Erb's | NR | NR | ||

| Axilla | 20.5 | 0.8 | 54 | ||

| Above Elbow | 19.2 | 0.9 | 50 | ||

| Below Elbow | 17.2 | 0.9 | 16 | ||

| Wrist | 7.2 | 2.1 | |||

| Sensory Nerve Conduction Studies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerve | Stimulation site | Onset latency (ms) | Amplitude Sensory (μV) | Conduction velocity (m/s) |

| Left Median | Palm-wrist | 1.2 | 138.4 | 58 |

| Dig II- wrist | 2.1 | 63.8 | 52 | |

| Left Ulnar | Palm-wrist | 1.4 | 3.9 | 44 |

| Dig V-wrist | 2.1 | 2.4 | 43 | |

| Left Medial | 1.2 | 11.8 | 68 | |

| Antebrachial | ||||

| Left Lateral | 0.9 | 42.3 | 67 | |

| Antebrachial | ||||

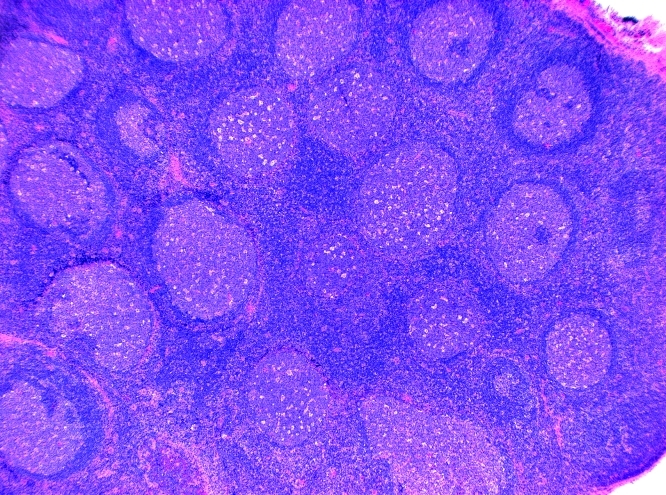

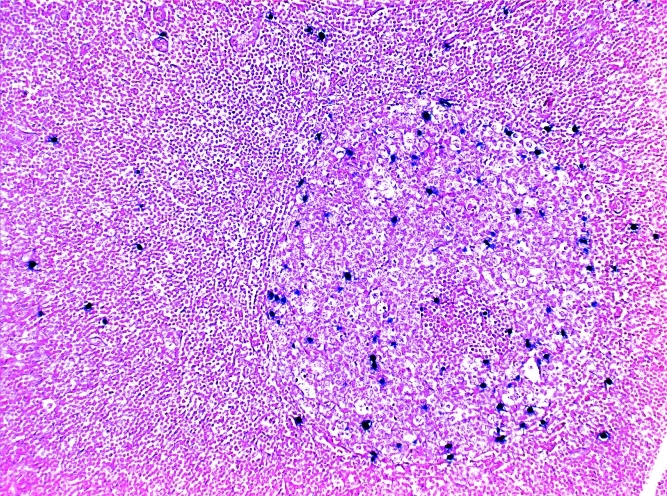

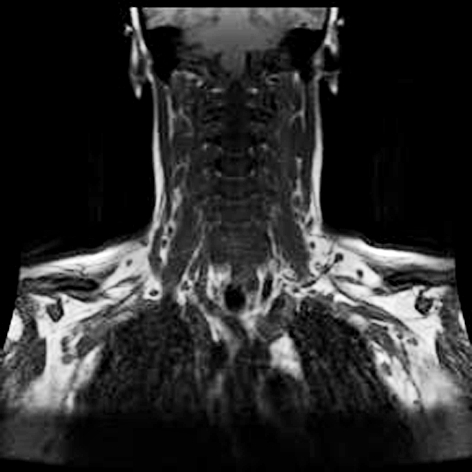

An MRI of the left brachial plexus was normal, without evidence of compression, but showed diffuse bilateral lymphadenopathy involving the neck, supraclavicular and axial regions (Fig. 1). The appearance suggested a diagnosis of lymphoma, and the patient was referred for lymph node biopsy that showed evidence of Epstein - Barr virus infection, but not lymphoma (Fig. 2). Serology was positive for EBV and CMV IgG, and HBs antibodies. Other lab tests were unremarkable, including TSH, ESR, ANA, vitamin B12, serum protein electrophoresis, Lyme titres, A1C, FBS, CBC, creatinine, liver function tests, rheumatoid factor, anti-ds DNA, C3, and C4 complement levels. Anti-GM1 Ganglioside antibodies were negative.

Figure 1. MR T1W coronal image showing diffuse cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy.

Figure 2. A) Lymph node biopsy: H&E-stained slide, showing prominent reactive follicular hyperplasia. B) Staining for EBER, a high power views shows the concentration of the EBER positive cells in a germinal centre.

The patient was treated with intravenous immunoglobulin, 2G/kg, without effect and with physiotherapy. She declined other interventions due to concerns about losing time from work. She is now 18 months following the onset of her neurological illness and remains stable.

Discussion

The literature contains a few case reports of radiculoplexopathy complicating acute EBV infection in children (3, 4). The prognosis for recovery was good in these cases. Our case is unique in that the brachial plexopathy occurred in an adult and her course is not as benign as previously described. Vucic et al. have reported a case similar to ours of brachial plexopathy in an adult with acute EBV infection (5). Our case differs in the prolonged temporal course between infection and weakness, complete lack of pain, and lack of improvement at 18 months after onset. It is unique as being the first case of a biopsy documented EBV lympho-adenopathy associated with painless focal amyotrophy. It is interesting to speculate about the mechanism of nerve injury in our patient. Compression by the lymphadenopathy should be considered due to the extensive nature of the lymph node enlargement and the involvement of the lower part of the brachial plexus presenting as a thoracic outlet syndrome. Still, the brachial plexus involvement is of the lower plexus only and the lymphadenopathy is extensive. This discrepancy and the lack of pain suggest that compression is not the most likely mechanism. Post-infectious demyelination caused by EBV infection analogous to brachial neuritis needs to be considered. Confounding both of these diagnoses is the lack of pain at any time during the course of her illness. Furthermore, post-infectious brachial plexopathies more typically involve upper parts of the plexus.

Other diagnosis that we considered in this patient were: monomelic amyotrophy/Hirayama disease in which a history of progression for several years prior to stabilization and a lack lymphadenopathy and demyelination on nerve conduction studies are expected; multifocal motor neuropathy characterized by lack of sensory involvement and positive response to IVIG; multifocal CIDP characterized by response to IVIG and lack of EB positive lymphadenopathy; and hereditary predisposition to pressure palsies with expected positive family history, conduction blocks at compressive sites, and histories of nerve palsies with spontaneous improvement. Our patient did not have the characteristics of these disorders but had onset of her neurological disorder 2-3 weeks after a viral infection suggesting a causal relationship and points out the need to include EBV infection with lymphadenopathy in the differential diagnosis of lesions involving the lower trunk of the brachial plexus and presenting with painless amyotrophy of the hand.

References

- 1.Portegies P, Corssmit N. Epstein-Barr Virus and the Nervous System. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2000;13:301–304. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200006000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Gilden DH. The Expanding Spectrum of Herpesvirus Infections of the Nervous system. Brain Pathology. 2001;11:440–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2001.tb00413.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dussaix E, Touzé P, Tardieu M. Neuropathy of the brachial plexus complicating infectious mononucleosis in an 18-month-old child. Arch Fr Pediatr. 1986;43:129–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janes SE, Whitehouse WP. Brachial Neuritis Following Infection with Epstein-Barr virus. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2003;7:413–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vucic S, Palmer W, Cros D. Radiculoplexopathy with Conduction Block Caused by Acute Epstein-Barr Virus Infection. Neurology. 2005;64:530–532. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150582.80346.2C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]