Abstract

Colorectal cancer is a complex disease resulting from somatic genetic and epigenetic alterations, including locus-specific CpG island methylation and global DNA or LINE-1 hypomethylation. Global molecular characteristics such as microsatellite instability (MSI), CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), global DNA hypomethylation, and chromosomal instability cause alterations of gene function in a genome-wide scale. Activation of oncogenes including KRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA affects intracellular signaling pathways and has been associated with CIMP and MSI. Traditional epidemiology research has investigated various factors in relation to an overall risk of colon and/or rectal cancer. However, colorectal cancers comprise a heterogeneous group of diseases with different sets of genetic and epigenetic alterations. To better understand how a particular exposure influences the carcinogenic process, somatic molecular changes and tumor biomarkers have been studied in relation to the exposure of interest. Moreover, an investigation of interactive effects of tumor molecular changes and the exposures of interest on tumor behavior (prognosis or clinical outcome) can lead to a better understanding of tumor molecular changes, which may be prognostic or predictive tissue biomarkers. These new research efforts represent “Molecular Pathologic Epidemiology”, which is a multidisciplinary field of investigations of the interrelationship between exogenous and endogenous (e.g., genetic) factors, tumoral molecular signatures and tumor progression. Furthermore, integrating genome-wide association studies (GWAS) with molecular pathologic investigation is a promising area. Examining the relationship between susceptibility alleles identified by GWAS and specific molecular alterations can help elucidate the function of these alleles and provide insights into whether susceptibility alleles are truly causal. Although there are challenges, molecular pathologic epidemiology has unique strengths, and can provide insights into the pathogenic process and help optimize personalized prevention and therapy. In this review, we overview this relatively new field of research and discuss measures to overcome challenges and move this field forward.

Keywords: colorectal carcinoma; multistep carcinogenesis; etiologic; risk factor, survival; molecular change; prevention

Introduction to Molecular Pathologic Epidemiology

Molecular pathologic epidemiology, the concept of which has been consolidated by Ogino and Stampfer, [1] is a relatively new field of epidemiology based on molecular classification of cancer. In molecular pathologic epidemiology, a known or suspected etiologic factor is examined in relation to a specific somatic molecular change, in order to gain insights into the carcinogenic mechanism.[1] In recent years, there is a new direction of this field where we examine an interactive effect of tumoral molecular features and a lifestyle or other exposure factor on tumor behavior (prognosis or clinical outcome).[2] In this review, we focus on colorectal neoplasia, overview current status of molecular pathologic epidemiology, describe various challenges in this field, and propose future directions.

Molecular Classification of Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer is a disease which is characterized by uncontrolled growth of colorectal epithelial cells. According to the multistep carcinogenesis theory, [3, 4] colorectal epithelial cells accumulate a number of molecular changes and eventually become fully malignant cells. Genetic and epigenetic events during the carcinogenesis process differ considerably from tumor to tumor. Thus, colorectal cancer is not a single disease. Rather, colorectal cancer encompasses a heterogeneous complex of diseases with different sets of genetic and epigenetic alterations. Essentially, each tumor arises and behaves in a unique fashion that is unlikely to be exactly recapitulated by any other tumor.[5]

We typically classify colorectal cancers into categories according to a well-defined molecular feature (e.g., microsatellite instability, MSI-high vs. microsatellite stability, MSS), because substantial evidence suggests that tumors with similar characteristics (e.g., MSI-high) have arisen by similar mechanisms and will behave in a similar fashion.[5] Thus, the major purposes of molecular classification are: 1) to predict natural history (i.e., prognosis); 2) to predict response or resistance to a certain treatment or intervention; and 3) to examine the relationship between a certain etiologic factor (i.e., lifestyle, environmental or genetic) and a molecular subtype, so that we can provide evidence for causality and optimize preventive strategies.

For any marker for molecular classification, we need to consider two key points. The first question is whether a given molecular feature reflects genome-wide changes. For example, MSI, chromosomal instability (CIN), the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), and global DNA hypomethylation reflect genome-wide or epigenome-wide aberrations. Because these molecular features often confound the relationship between a locus-specific change and an exposure or outcome of interest, it is important to consider potential confounding by these genome-wide features whenever one examines locus-specific changes. The second question is whether a given molecular change has by itself driven cancer initiation or progression, or is simply linked to other important molecular events. For example, loss of heterozygosity (LOH) events may not by itself cause tumor progression; rather, underlying genomic instability (i.e., CIN) or functional loss of important genes within the lost chromosomal segment may cause tumor progression. Nevertheless, even if a given molecular change is consequential rather than causal, the change not only can be a good surrogate marker of a certain cancer pathway, but also may ultimately become a driver in later steps of tumor progression.

Emergence and Evolution of Molecular Pathologic Epidemiology

Traditional epidemiology research has investigated lifestyle, environmental or genetic factors that might increase or decrease risk of developing colorectal cancer.[6, 7] The weight of the evidence, in conjunction with results from in vitro and animal models or human experimental trials, can lead to particular factors being widely considered to be etiologically linked to cancer. Etiologic factors which have been implicated in colorectal carcinogenesis include red and processed meat, excess alcohol intake, deficiency of B and D vitamins, obesity, physical inactivity, diabetes mellitus, smoking, family history of colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel diseases, among others.[8] More recently, the field of molecular epidemiology has evolved since 1990s, encompassing genome-wide association studies (GWAS) since 2000s.[9, 10] Molecular epidemiology refers to a specialized field of epidemiology where investigators examine genetic and molecular variation in a population and its interaction with dietary, lifestyle or environmental factors, to find clues to plausible causative links between etiologic factors and diseases. However, the mechanisms with which plausible etiologic factors influence the carcinogenic process remain largely speculative.

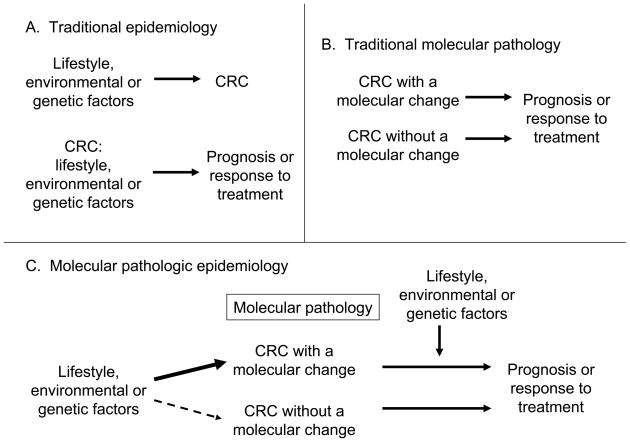

In traditional molecular pathology, investigators examine molecular characteristics in tumor cells to better understand carcinogenic processes and tumor cell behavior. In the last two decades, our knowledge on somatic molecular alterations in the carcinogenic process has substantially improved.[5, 11–16] As illustrated in Figure 1, these two approaches, epidemiology and molecular pathology, have converged to improve our understanding of how certain exposures influence carcinogenesis by examining molecular pathologic marks of tumor initiation or progression, in relation to the exposures of interest.[1] This represents a relatively new field of scientific investigation, which has been coined “Molecular Pathologic Epidemiology”.[1] If a specific lifestyle or dietary factor can prevent the occurrence of a specific somatic molecular change, it would add considerable scientific basis to such a preventive strategy. Specificity of the association for a certain molecular change provides further evidence for a causal relationship. For an individual who has a susceptibility to a specific somatic molecular change, we may be able to develop a personalized preventive strategy, which targets specific molecules or pathways.

Figure 1.

Illustration of traditional epidemiology (A), traditional molecular pathology (B), and molecular pathologic epidemiology (C). Note that molecular pathology plays a central role in molecular pathologic epidemiology. Molecular pathologic epidemiology addresses a question whether a particular exposure factor is associated with a specific molecular change in colorectal cancer (C, left side), as well as a question whether a specific molecular change can interact with a particular exposure factor to affect tumor cell behavior (C, right side). The latter represents a new direction of molecular pathologic epidemiology where results can provide additional insights on mechanism of how the tumoral molecular change and the exposure factor of interest influence tumor cell behavior. CRC, colorectal cancer.

Table 1 is a comprehensive list of molecular pathologic epidemiology studies on colorectal neoplasia.[17–45][46–88][89–101][102–151] One challenge is that, despite a number of studies on some topics (e.g., one-carbon metabolism gene polymorphisms and epigenetic changes), generalisable confirmed findings are uncommon. We discuss possible reasons and various challenges in a later section. Nonetheless, there have been observations confirmed by notable independent studies: a case-control study by the Slattery et al.’s group[114] and a prospective cohort study by Iowa Women’s Health Study (IWHS)[78] have independently shown that cigarette smoking is associated with CIMP-positive tumor, and with BRAF-mutated tumor. As another example, the association between obesity and microsatellite stable (MSS) tumor has been demonstrated by three independent case-control studies, including the Slattery et al.’s group, [123] North Carolina Colon Cancer Study (NCCCS), [116] and Colon Cancer Family Registry (CCFR).[35] With regard to germline genetic variants and molecular changes, MLH1 rs1800734 promoter SNP has been associated with MSI-high tumors in three independent case-case and case-control studies, [38, 108, 115] and MGMT rs16906252 promoter SNP has been associated with MGMT promoter methylation and loss of expression in colorectal cancer[94] and normal colorectal mucosa and peripheral blood cells in individuals without cancer.[152, 153] These consistent data across different studies increase validity of each other’s findings and support etiologic roles of cigarette smoking, obesity and germline variants in specific pathways of colorectal carcinogenesis. Ultimately, our understanding of these specific neoplasia pathways will clarify areas for disease intervention.

Table 1.

Molecular pathologic epidemiology studies on possible etiologic factors and molecular changes in colorectal neoplasia

| Ref. | First author | Year | Study design | Tissue specimens | Study cohort, sample sizes (N)* and notes | Exposure variables | Potential modifiable factors | Outcome variables | Main findings on modifiable (or genetic) factors and tumoral molecular changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case-case studies | |||||||||

| [17] | Arain | 2010 | Case-case | CC | 194 CC (63 interval CC), 0 non-cancer controls | Colonoscopy within 5 years prior to diagnosis of CC (interval cancer) | CIMP, MSI in CC | Colonoscopy within 5 years prior to diagnosis of CC is associated with CIMP and MSI in CC. | |

| [18] | Baba | 2009 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 621 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | CDX2 expression in CRC | BMI or family history of CRC is not significantly associated with loss of CDX2 expression in CRC. | |

| [19] | Baba | 2009 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 517 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | AURKA expression in CRC | BMI or family history of CRC is not significantly associated with AURKA expression in CRC. | |

| [20] | Baba | 2010 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 516 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | HIF1A, EPAS1 (HIF-2A) expression in CRC | BMI or family history of CRC is not significantly associated with HIF1A or EPAS1 expression in CRC. | |

| [21] | Baba | 2010 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 731 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | PTGER2 (prostaglandin EP2 receptor) expression in CRC | BMI or family history of CRC is not significantly associated with PTGER2 expression in CRC. | |

| [22] | Baba | 2010 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 869 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family hisotry of CRC, smoking | LINE-1 methylation in CRC | Family history of CRC may be associated with LINE-1 hypomethylation in CRC. LINE-1 extreme hypomethylators are associated with young age of onset. | |

| [23] | Baba | 2010 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 1105 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | IGF2 differentially methylated region-0 (DMR0) hypomethylation in CRC | Family history of CRC is associated with IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation. | |

| [24] | Baba | 2010 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 718 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | phospho-PRKA (AMPK) expression in CRC | Family history of CRC or BMI is not associated with phospho-PRKA (AMPK) expression in CRC. | |

| [25] | Baba | 2010 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 717 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | phospho-AKT expression in CRC | Family history of CRC or BMI is not associated with phospho-AKT expression in CRC. | |

| [26] | Bapat | 2009 | Case-case | CRC | CCFR.3143 CRC | Family history of CRC and endometrial cancer | MSI in CRC | Family history of CRC and endometrial cancer is associated with MSI-high in CRC. Familial risk associated with MSI-high CRC is primarily driven by the Amsterdam criteria patients. | |

| [30] | Brink | 2003 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NLCS.737 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | Family history of CRC | KRAS mutation in CRC | Family history of CRC is not associtade with KRAS mutation in CRC | |

| [37] | Chang | 2007 | Case-case | CRC | 195 CRC | MTHFR codon 222 SNP, plasma folate | MSI, aneuploidy in CRC | MTHFR codon 222 variant is associated with MSI-H CRC. Plasma folate is lower in aneuploid MSS CRC than in diploid MSS CRC. | |

| [38] | Chen | 2007 | Case-case | CRC | 387 CRC | MLH1 SNPs | MLH1 methylation in CRC | MLH1 rs1800734 (−93G>A) SNP is associated with MLH1 methylation in CRC. | |

| [40] | Clarizia | 2006 | Case-case | CRC | 105 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | MTHFR codon 222 SNP | MSI, methylation in MLH1, CDKN2A, MGMT, DAPK1, p14 in CRC | MTHFR codon 222 SNP variant is associated with MSI-H in CRC. | |

| [52] | Eaton | 2005 | Case-case | CC | NCCCS.486 CC, 0 non-cancer controls | MTHFR SNPs | Dietary and supplement folate | MSI in CRC | Among high folate intake group (≥400 ug/day), the presence of either MTHFR SNP variant is associated with MSS. |

| [54] | Fernandez-Peralta | 2010 | Case-case | CRC | 143 CRC | MTHFR SNPs | MSI, LOH at APC, DCC, TP53, MLH1, MSH2, mutation in KRAS, BAX, TGFBR2 in CRC | None of molecular feature in CRC is differentially related to MTHFR SNP with certainty. | |

| [55] | Ferraz | 2004 | Case-case | CRC | 165 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1, NAT2 genotypes | KRAS, TP53 mutations in CRC | GSTT1 or GSTP1 SNPs may be associated with KRAS or TP53 mutations in CRC. | |

| [57] | Firestein | 2010 | Case-case(in PCS) | CRC | 470 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis) | CDK8 expression in CRC | Female sex is associated with CDK8 expression in CRC. BMI (prediagnosis) is not associated with CDK8 expression in CRC. | |

| [58] | Gonzalo | 2010 | Case-case | CRC | 82 CRC patients (37 synchronous CRC patients, 4 metachronous CRC patients) | Tumor synchronicity/metachronicity | Methylation in MGMT, CDKN2A, SFRP1, TMEFF2, HS3ST2, RASSF1, GATA4 in CRC | Tumor synchronicity/metachronicity is associated with methylation in MGMT and RASSF1 in CRC. | |

| [59] | Gruber | 2007 | Case-case | CRC | MECCS (northern Israel). 133 CRC | SNP rs10505477 in 8q24 | mRNA expression of genes in 8q24 in CRC | SNP rs10505477 is not associated with any difference in expression of examined genes in 8q24. | |

| [60] | Hansen | 2010 | Case-case | CRC | 109 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | KDR SNPs | Microvessel density (assessed by immunohisto-chemistry for ENG and CD34) in CRC | KDR rs2305948 SNP T variant is associated with high microvessel density. | |

| [61] | Hazra | 2010 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS.182 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | SNPs in one-carbon metabolism genes | CIMP, LINE-1 methylation in CRC | MTHFR rs1801131 (codon 429) and TCN2 rs1801198 SNP variants are associated with CIMP-high in CRC. | |

| [62] | Huang | 2009 | Case-case | CRC | 151 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | NAT2 genotypes | KRAS mutation in CRC | NAT2 genotype may be associated with KRAS mutation in CRC in female. | |

| [65] | Irahara | 2010 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 225 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | NRAS mutation in CRC | There is no association between BMI or family history of CRC and NRAS mutation in CRC. | |

| [67] | Jensen | 2008 | Case-case | CRC | 130 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | Plasma homocysteine | MSI in CRC | MSI-H cases show higher plasma homocysteine level than MSS cases. | |

| [68] | Kang | 2008 | Case-case | CRC | 188 CRC | p14 (CDKN2A/ARF) SNPs | p14 methylation in CRC | p14 promoter SNP haplotype is associated with p14 methylation in CRC. | |

| [70] | Kawakami | 2003 | Case-case | CRC | 103 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | TYMS, MTHFR, MTR, CBS genotypes | 5, 10-methylene-tetrahydrofolate, tetrahydrofolate, methylation in MLH1, TIMP3, p14 (CDKN2A/ARF), CDKN2A, MINT-2, DAPK, APC in CRC | MTHFR rs1801133 SNP (codon 222) with decreased 5,10-methylene-tetrahydrofolate and tetrahydrofolate contents in CRC. homozygous variant is associated | |

| [71] | Konishi | 2009 | Case-case | CRC | 97 CRC patients (28 synchronous CRC patients) | Tumor synchronicity | Methylation in MINT-1, MINT-2, MINT-31, MLH1, CDKN2A, p14, MGMT, ESR1 in CRC | Synchronous CRC is associated with higher methylation levels at p14 methylation level at MINT-31 in CRC. (CDKN2A/ARF) and MGMT and lower | |

| [72] | Kure | 2009 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 619 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | VDR expression in CRC | BMI or family history of CRC is not significantly associated with VDR expression in CRC. | |

| [74] | Langerod | 2002 | Case-case | CRC | 162 CRC, 0 controls | TP53 codon 72 SNP | TP53 mutation in CRC | TP53 codon 72 SNP is not related to TP53 mutation in CRC, but to TP53 mutation in breast cancer (N=390). | |

| [79] | Lindor | 2010 | Case-case | CRC | CCFR. 789 CRC | Parent of origin family history of CRC | MSI in CRC | Among overall CRC cases, HNPCC, or MSS cancer cases, family history of CRC in father is associated with lower age of onset of CRC in daughters than in family history of CRC in mother, but no such difference in age of onset is present among affected sons. | |

| [81] | Lubbe | 2009 | Case-case | CRC | NSCCG. 488 CRC | Family history of CRC in first degree relatives | MSI in CRC | Family history of CRC in first degree relatives is associated with MSI-H CRC. | |

| [84] | Luchtenborg | 2005 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NLCS. 656 CRC | Family history of CRC | APC, KRAS mutation, MLH1 loss in CRC | APC, KRAS or MLH1 alteration is not associated with family history of CRC. | |

| [85] | Martinez | 1999 | Case-case | CRA | WBFT. 678 CRA, 0 non-cancer controls | Various nutrients, alcohol, family history, aspirin use, smoking, BMI, physical activity, hormone use | KRAS mutation in CRA | Folate intake is inversely associated with KRAS mutation in CRA. | |

| [86] | Mas | 2007 | Case-case | CRC | 120 CRC, 0 con-cancer controls | Various nutrients | CDKN2A (p16), p14, MLH1 methylation in CRC | Patents with CDKN2A methylation consumed less folate, vitamin A, vitamin B1, potassium and iron. Patients with p14 or MLH1 methylation consumed less vitamin A. |

|

| [87] | Mokarram | 2008 | Case-case | CC | 151 CC, 0 non-cancer controls | Folate, vitamin B12 in serum | MTHFR rs1801133 SNP | Methylation in MLH1, MSH2, CDKN2A (p16) in CC | Relation between folate/B12 and methylation in CC may be modified by MTHFR rs1801133 (codon 222) SNP. |

| [89] | Naguib | 2010 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | EPIC-Norfolk Study. 186 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI, smoking, physical activity, HRT, alcohol, dietary factors | KRAS and BRAF mutations in CRC | KRAS-mutated tumors are associated with higher white meat consumption, compared to KRAS-wild-type tumors. | |

| [91] | Nosho | 2009 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 863 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | Tumor synchronicity | BMI, family history of CRC | MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, 18q LOH, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, CTNNB1, CDKN1A (p21), CDKN1B (p27), CCND1, FASN, PTGS2 (COX-2) in CRC | Tumor synchronicity is associated with CIMP-high, MSI-H, and BRAF mutation. There is no significant modifying effect by BMI or family history of CRC. |

| [92] | Nosho | 2009 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 485 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | SIRT1 expression in CRC | BMI or family history of CRC is not significantly associated with SIRT1 expression in CRC. | |

| [93] | Nosho | 2009 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 766 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | JC virus T antigen expression in CRC | Family history of CRC may be inversely associated with JC virus T antigen expression in CRC. | |

| [94] | Ogino | 2007 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 182 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | MGMT SNPs | MGMT methylation, CIMP, MSI, 18q LOH, KRAS, BRAF mutation in CRC | MGMT rs16906252 SNP variant is associated with MGMT methylation (adjusted OR=18; 95% CI, 6.2–52) and loss of expression. | |

| [2] | Ogino | 2008 | Case-case (in PCS) | CC | NHS, HPFS. 623 CC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis) | FASN expression in CRC | There is an inverse relation between BMI and FASN expression in CRC. | |

| [95] | Ogino | 2009 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 470 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | PPARG expression in CRC | There is no relation between BMI or family history of CRC and PPARG expression in CRC. | |

| [96] | Ogino | 2009 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 546 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | STMN1 expression in CRC | There is no relation between BMI or family history of CRC and STMN1 expression in CRC. | |

| [97] | Ogino | 2009 | Case-case (in PCS) | CC | NHS, HPFS. 450 CC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis) | PIK3CA mutation in CC | There is no relation between BMI and PIK3CA mutation in CC. | |

| [98] | Ogino | 2009 | Case-case (in PCS) | CC | NHS, HPFS. 630 CC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | CDKN1B (p27) localization in CC | There is no relation between BMI or family history of CRC and CDKN1B (p27) localization in CC. | |

| [99] | Ogino | 2009 | Case-case (in PCS) | CC | NHS, HPFS. 647 CC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | CDKN1A (p21) expression in CC | There is no relation between BMI or family history of CRC and CDKN1A (p21) expression in CC. | |

| [100] | Ogino | 2009 | Case-case (in PCS) | CC | NHS, HPFS. 602 CC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | CCND1 (cyclin D1) expression in CC | There is no relation between BMI or family history of CRC and CCND1 expression in CC. | |

| [101] | Ogino | 2009 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 555 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC | 18q LOH in CRC | Obesity (prediagnosis) is associated with 18q LOH in CRC. | |

| [102] | Oyama | 2004 | Case-case | CRC | 194 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | MTHFR SNPs | Methylation in CDKN2A, MLH1, TIMP3, p14 in CRC | MTHFR codon 429 SNP variant is associated with CDKN2A methylation in CRC. | |

| [103] | Park | 2010 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | EPIC-Norfolk Study. 185 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | Dietary factors, family history, BMI, physical activity, smoking | TP53 mutation in CRC | There is a positive relation between meat intake and TP53 mutation in Duke’s stage C and D cases, while there is a positive relation between meat intake and wild-type TP53 in Duke’s stage A and B cases. | |

| [104] | Paz | 2002 | Case-case | CRC | 118 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | Genotypes of one-carbon metabolism genes | Methylation in CDKN2A, p14, MLH1, MGMT, APC, STK11, DAPK1, GSTP1, BRCA1, RARB, CDH1, RASSF1 in CRC | Results on all cancers (CRC, breast presented, and CRC-specific results are not presented. cancers, and lung cancers) are | |

| [109] | Ricciardiello | 2003 | Case-case | CRA | 70 CRA | Family history of CC | MSI, MLH1 methylation, expression of MLH1 and MSH2 in CRA | Family history of CC is associated with MLH1 methylation and loss of MLH1 in CRA. | |

| [110] | Rozek | 2008 | Case-case | CRC | MECCS (northern Isreal). 82 CRC | CDX2 SNPs and haplotypes | CDX2 mRNA expression in CRC | CDX2 SNPs or haplotypes are not associated with CDX2 mRNA expression in CRC. | |

| [112] | Samowitz | 1995 | Case-case | CC | 188 CC | Family history of CRC, GSTM1 genotype | MSI in CC | Family history of CRC or GSTM1 genotype is not associated with MSI in CC. | |

| [121] | Shima | 2010 | Case-case (in PCS) | CRC | HPFS, NHS. 902 CRC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI, family history of CRC | CDKN2A (p16) promoter methylation, loss of CDKN2A in CRC | There is no relation between BMI or family history of CRC and CDKN2A methylation (or loss of expression) in CRC. | |

| [122] | Sinicrope | 2010 | Case-case | CC | 7 colon cancer adjuvant therapy trials. 2222 CC, 0 non-cancer controls | BMI | Mismatch repair protein loss (or MSI-H) in CC | High BMI is inversely associated with MSI in CC. | |

| [141] | van Engeland | 2003 | Case-case | CRC | NLCS. 121 CRCs,0 non-cancer controls. | Various nutrients, alcohol | Methylation in APC, CDKN2A (p16), p14, MLH1, MGMT, RASSF1A in CRC | Folate and alcohol intake may be associated with promoter hypermethylation in CRC. | |

| [143] | Ward | 2004 | Case-case | CRC | 547 CRC | Family history of CRC, family history of any cancer | CIMP in CRC | CIMP in CRC is not associated with family history of CRC or any cancer. | |

| [149] | Wu | 2001 | Case-case | CC | Los Angeles County Cancer Surveillance Program (a part of SEER). 276 CC, 0 non-cancer controls | Smoking, red meat cooking practice | MSI in CC | Certain red meat cooking (well-doing) and heterocyclic amine score are associated with MSI-H CC. Smoking is associated with MSI-H CC. | |

| [150] | Wu | 2010 | Case-case | CC | Los Angeles County Cancer Surveillance Program (a part of SEER). 280 CC | Hormone therapy | ESR1, ESR2, PGR, CDKN2A, MGMT, MYOD1, MLH1 methylation in CC | There may be an inverse association between hormone therapy and ESR1 methylation in CC. | |

| Case-cohort studies | |||||||||

| [28] | Bongaerts | 2006 | Case-cohort study | CRC | NLCS. 4076 subcohort, 578 CRC | Alcohol intake | KRAS mutation in CRC | Alcohol intake does not influence KRAS mutation in CRC. | |

| [29] | Bongaerts | 2007 | Case-cohort study | CRC | NLCS. 4076 subcohort, 573 CRC | Alcohol intake | KRAS, APC mutation, TP53 expression, MLH1 loss in CRC | Alcohol intake does not influence KRAS, APC mutation, TP53 or MLH1 alteration in CRC. | |

| [31] | Brink | 2004 | Case-cohort study | CRC | NLCS. 2948 subcohort, 608 CRC | Various fat components | KRAS mutation in CRC | High intake of polyunsaturated fat is associated with risk of KRAS-mutated CC. | |

| [32] | Brink | 2005 | Case-cohort study | CRC | NLCS. 2948 subcohort, 608 CRC | Meat consumption | KRAS mutation in CRC | There may be an inverse association between pork consumption and KRAS wild-type CRC. | |

| [33] | Brink | 2005 | Case-cohort study | CRC | NLCS. 3048 subcohort, 330 CRC | Various nutrients | KRAS mutation in CRC | Folate intake is associated with lower risk of KRAS-mutated CRC in men, but not in women. | |

| [46] | de Vogel | 2006 | Case-cohort study | CRC | NLCS. 4343 subcohort. 547 CRC with APC data | Various nutrients | APC mutation in CRC | Folate may influence the occurrence of APC mutation in CRC. | |

| [47] | de Vogel | 2008 | Case-cohort study | CRC | NLCS. 4059 subcohort. 648 CRC | Various nutrients | MLH1 methylation, MLH1 expression, MSI, BRAF mutation in CRC | Among men, folate intake may increase risk of BRAF-mutated CRC, and vitamin B6 may increase risk of MLH1 methylated CRC. | |

| [48] | de Vogel | 2009 | Case-cohort study | CRC | NLCS. 4774 subcohort. 373 CRC | SNPs in folate enzyme genes metabolizing | CIMP, MLH1 methylation, MSI in CRC | MTR rs1805087 (A2756G) SNP is inversely associated with CIMP in men. | |

| [64] | Hughes | 2009 | Case-cohort study | CRC | NLCS. 4650 subcohort, 662 CRC | Hunger in adolescence and young adulthood | CIMP, MSI in CRC | Exposure to hunger in young age is associated with decreased risk of CIMP+ CRC, but not associated with CIMP-negative CRC. | |

| [82] | Luchtenborg | 2005 | Case-cohort study | CRC | NLCS. Subcohort 2948. 588 CRC | Meat and fish consumption | APC mutation, MLH1 loss in CRC | Beef consumption is associated with risk of CC without APC mutation. | |

| [83] | Luchtenborg | 2005 | Case-cohort study | CRC | NLCS. Subcohort 2948. 650 CRC | Smoking | GSTM1, GSTT1 genotypes | APC mutation, MLH1 loss in CRC | Smoking increases risk of APC-WT CRC, and there is no modifying effect of GSTM1 or GSTT1 genotypes. |

| [144] | Wark | 2005 | Case-cohort study | CRC | NLCS. 3048 subcohort, 441 CC | Fruits, vegetable consumption | MLH1 loss in CC | Fruits consumption decrease risk of MLH1-lost CC, but not that of MLH1-expressing CC. | |

| [146] | Weijenberg | 2007 | Case-cohort study | CRC | NLCS. 2948 subcohort, 531 CRC | Various fat components | APC, KRAS mutation, MLH1 loss in CRC | High intakes of polyunsaturated fatty acid and linoleic acid increase risk of KRAS-mutated CC. | |

| [147] | Weijenberg | 2008 | Case-cohort study | CRC | NLCS. 4083 subcohort, 428 CRC | Smoking | KRAS mutation in CRC | Effect of smoking on CRC risk is not different according to KRAS mutational status. | |

| Case-control studies (CCS) | |||||||||

| [27] | Bautista | 1997 | CCS | CRC | 106 CRC, 295 controls | Various nutrients | KRAS mutation in CRC | Monounsaturated fat is inversely associated with KRAS wild-type CRC compared to controls, but no such association is present for KRAS-mutated CRC. | |

| [34] | Campbell | 2009 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1211 CC, 1972 controls | SNPs in MLH1, MSH6 | Smoking, dietary pattern | MSI in CC | Smoking does not modify MSI-H CC risk that is conferred by MLH1 rs1800734 (−93G>A) SNP. |

| [35] | Campbell | 2010 | CCS | CRC | CCFR. 1250 CRC, 1880 controls (unaffected siblings) | BMI, BMI at age 20, weight gain | MSI in CRC | Obesity is associated with MSS CRC risk, but not with MSI-H CRC risk. | |

| [39] | Chia | 2006 | CCS | CRC | CCFR. 1792 CRC, 1501 controls. | Smoking, NSAIDs | MSI in CRC | Smoking is associated with increased risk of MSI-H CRC, but not strongly with that of MSI-L/MSS CRC. | |

| [41] | Curtin | 2007 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 916 CC, 1972 controls | SNPs in one-carbon metabolism genes | One-carbon nutrients, alcohol, dietary pattern | CIMP in CC | MTHFR rs1801131 (codon 429) SNP may interact with alcohol intake and dietary pattern to modify CIMP+ CC risk. |

| [42] | Curtin | 2007 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1206 CC, 1962 controls | TYMS SNPs | MSI, TP53, KRAS mutations in CC | TYMS SNPs are not differentially associated with CC by MSI, TP53 or KRAS status. | |

| [43] | Curtin | 2009 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1604 CC, 1969 controls | SNPs in base excision repair genes | Smoking | MSI, CIMP, mutations in BRAF, KRAS, TP53 in CC | There is no significant effect modification by smoking status. |

| [44] | Curtin | 2009 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1048 CC, 1964 controls | MSH6 rs1042821 SNP | Alcohol intake, age, family history | CIMP, MSI, BRAF mutation in CC | MSH6 rs1042821 SNP is associated with CIMP+ CC, and this relation is not modified by alcohol intake, age at diagnosis or family history. |

| [45] | Curtin | 2009 | CCS | Rectal cancer | KPMCP-UT-MN. 750 rectal cancers, 1201 controls | GSTM1, NAT2 genotypes | Smoking | MSI, CIMP, TP53, KRAS, BRAF mutation in rectal cancers | Smoking is associated with CIMP, TP53, BRAF mutation in rectal cancer. |

| [49] | Diergaarde | 2003 | CCS | CC | Population-based case-control study in The Netherlands. 176 CC, 249 controls | Smoking | KRAS, TP53, APC mutations, MSI in CC | Smoking may be associated with transversion mutations and with TP53-negative CC. | |

| [50] | Diergaarde | 2003 | CCS | CC | Population-based case-control study in The Netherlands. 184 CC, 259 controls | Various food and nutrients | MSI, MLH1 methylation, expression of MLH1 and MSH2 in CC | Red meat intake may differentially modify CC risk stratified by MSI status. | |

| [51] | Diergaarde | 2003 | CCS | CC | Population-based case-control study in The Netherlands. 184 CC, 259 controls | Various food and nutrients | APC mutation in CC | Alcohol intake may differentially modify CC risk stratified by APC mutation status. | |

| [56] | Figueiredo | 2010 | CCS | CRC | CCFR. 1200 CRC, 1880 matched unaffected sibling controls. | FOLR1, FPGS, GGH, SLC19A1 SNPs | Dietary one-carbon nutrients | MSI in CRC | CRC risks associated with any SNP do not significantly differ by MSI status. |

| [63] | Hubner | 2007 | CCS | CRC | NSCCG. 1649 CRC, 2692 non-cancer controls | MTHFR rs1801133 SNP | MSI in CRC | MTHFR rs1801133 SNP (codon 222) variant is associated with MSI-H CRC compared to controls, but not with MSS CRC. | |

| [66] | Jacobs | 2010 | CCS | CRC | CCFR. 1182 CRC, 1880 matched unaffected sibling controls. | SNPs in RXRA, CASR | MSI in CRC | RXRA SNP rs12004589 is associated with MSI-high cancer, but not with MSS/MSI-low cancer. | |

| [69] | Karpinski | 2010 | CCS | CRC | 186 CRC, 140 con-cancer controls | MTHFR, TYMS, DNMT3B genotypes | CIMP in CRC | Compared to controls, DNMT3B - 283T>C SNP is associated inversely with CIMP+ CRC, but not with CIMP− CRC. | |

| [73] | Lafuente | 2000 | CCS | CRC | 117 CRC, 296 controls | NQO1 SNP | KRAS mutation in CRC | KRAS codon 12 mutations are associated with NQO C609T SNP. | |

| [75] | Laso | 2004 | CCS | CRC | 117 CRC, 296 controls | Micro-nutrients | KRAS mutation in CRC | KRAS codon 12 mutations are associated with lower intake of vitamin A, B1, D and iron than controls. | |

| [76] | Levine | 2010 | CCS | CRC | CCFR. 1133 CRC, 1787 controls (unaffected siblings) | MTHFR SNPs | MSI in CRC | MTHFR rs1801133 (codon 222) SNP variant is associated with a decreased risk of MSI-L/MSS CRC. | |

| [77] | Levine | 2010 | CCS | CRC | CCFR. 1185 CRC, 1787? controls (unaffected siblings) | SNPs of one-carbon metabolism genes | Folate and multi-vitamin supplement use, dietary folate, family history of CRC | MSI in CRC | SNPs of one-carbon metabolism genes are not associated with CRC differently by MSI status. |

| [80] | Lindor | 2010 | CCS | CRC | CCFR. 940 CRC, 940 controls | Smoking, SERPINA1 SNP | MSI in CRC | Smoking is associated with MSI-H CRC in patients ≥age 50. | |

| [88] | Naghibalhos saini | 2010 | CCS | CRC | 151 CRC, 231 controls | MTHFR SNPs (rs1801133, rs1801131) | MSI in CRC | There is no significant difference in risks associated with MTHFR SNPs between MSI and MSS cancers. | |

| [90] | Newcomb | 2007 | CCS | CRC | Cancer Surveillance System (a part of SEER). 311 CRC, 1062 controls | Exogenous hormone use | MSI in CRC | The relation between hormone use and CRC risk does not differ by MSI status. | |

| [105] | Plaschke | 2003 | CCS | CRC | 287 CRC, 346 controls | MTHFR SNPs | MSI in CRC | MTHFR SNPs are not associated with MSI-H CRC. | |

| [106] | Poynter | 2009 | CCS | CRC | CCFR. Case-unaffected sibling design. 1564 CRC, 4486 controls | Smoking, alcohol | MSI in CRC | Smoking is associated with increased risk of MSI-H CRC (OR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.09–3.46). Alcohol intake is associated with increased risk of MSI-L CRC (OR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.06–3.24). | |

| [107] | Poynter | 2010 | CCS | CRC | CCFR. Case-unaffected sibling design. 1200 CRC, 1880 controls | VDR, GC SNPs | MSI in CRC | GC rs222029, rs222016 and rs16847039 SNPs are associated with lower risk of MSI-H CRC, but not associated with MSS CRC. | |

| [108] | Raptis | 2007 | CCS | CRC | 766 CRC, 1098 controls | MLH1, MSH2 SNPs | MSI in CRC | MLH1 rs1800734 (−93G>A) SNP is associated with MSI-H CRC. | |

| [111] | Rozek | 2010 | CCS | CRC | MECCS (northern Isreal). 1297 CRC, 2019 matched controls | Ethnicity, smoking, family history of CRC | BRAF mutation in CRC | Men who smoked are more likely to have BRAF-mutated tumor than women who never smoked. | |

| [113] | Samowitz | 2006 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1510 CC, 1981 controls | IRS1, IRS2, IGF1, IGFBP3 SNPs | MSI, KRAS, TP53 mutations in CC | IRS1 G972R SNP is associated with MSI CC. | |

| [114] | Samowitz | 2006 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1315 CC, 2392 controls | Smoking | CIMP, BRAF mutation in CC | Smoking ≥20 cigarettes/day is associated with CIMP+ (OR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.43–2.97) and BRAF mutation (OR, 3.16; 95% CI, 1.80–5.54) compared to controls, but smoking is not associated with CIMP-negative or BRAF-WT. | |

| [115] | Samowitz | 2008 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 795 CC, 1968 controls | MLH1 rs1800734 SNP | MSI, CIMP, BRAF mutation in CC | MLH1 rs1800734 (−93G>A) SNP is associated with CIMP, MLH1 methylation and BRAF mutation in MSI-H CC. | |

| [116] | Satia | 2005 | CCS | CC | NCCCS. 486 CC, 1048 controls | Various food and nutriens, BMI, smoking, physical activity, family history, NSAIDs, vitamin mineral supplements | MSI in CC | No dietary factor is differentially related to MSI-H compared to MSI-L/MSS CC. | |

| [120] | Shannon | 2002 | CCS | CRC | 456 CRC, 1207 controls | MTHFR SNP, CBS polymorphisms | MSI in CRC | CBS 844ins68 variant is inversely associated with MSI in proximal CRC. | |

| [123] | Slattery | 2000 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1510 CC, 2410 controls | BMI, physical activity, smoking, aspirin, NSAIDs | MSI in CC | Among both men and women, cigarette smoking is associated with MSI but not with MSS. | |

| [124] | Slattery | 2000 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1428 CC, 2410 controls | Various food and nutrients | KRAS mutation in CC | Low cruciferous vegetable intake may be differentially associated with KRAS mutation vs. WT (p=0.01). | |

| [125] | Slattery | 2001 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1428 CC, 2410 controls | BMI, dietary pattern, physical activity, smoking, aspirin, NSAIDs | KRAS mutation in CC | Among men, but not women, low physical activity is associated with KRAS mutation but not with KRAS-WT. | |

| [126] | Slattery | 2001 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1510 CC, 2410 controls | Various food and nutrients | MSI in CC | Alcohol intake may increase MSI cancer risk. | |

| [127] | Slattery | 2001 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1510 CC, 2410 controls | Oral contraceptive use, Estrogen replacement, number of pregnancies, BMI, physical activity | MSI in CC | Estrogen exposure in women may decrease MSI cancer risk. | |

| [128] | Slattery | 2002 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1457 CC, 2410 controls | Family history of CRC | MSI, KRAS, TP53 mutations in CC | Family history of CRC is not differentially associated with CC risk by MSI, KRAS or TP53 status. | |

| [129] | Slattery | 2002 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1458 CC, 2410 controls | Diet, physical activity, BMI, smoking, aspirin/NSAIDs use, | TP53 mutation in CC | Western dietary pattern, red meat, and high glycemic load are associated with TP53 mutation in CC. | |

| [130] | Slattery | 2002 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1344 CC, 1958 controls | GSTM1, NAT2 genotypes | Smoking | MSI, TP53, KRAS mutation in CC | GSTM1 genotype and smoking may interact to influence occurrence of KRAS mutation in CC. |

| [131] | Slattery | 2006 | CCS | CRC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1577 CC (unknown number for molecular data), 1971 controls | PPARG P12A SNP | MSI, TP53, KRAS mutations in CC | It is unknown whether PPARG SNP differentially relates to CC risk by MSI, TP53 or KRAS status. | |

| [132] | Slattery | 2007 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1154 CC, 2410 controls | BMI, nutrients, physical activity, smoking, aspirin, NSAIDs | MSI, CIMP, BRAF mutation in CC | Obesity is associated with CIMP-negative, but not CIMP+ (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.5–2.6). Among MSI-high tumors, high alcohol intake is associated with BRAF-WT (OR 2.2; 95% CI, 1.2–3.7), but not among MSS tumors. | |

| [133] | Slattery | 2009 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1375 CC, 2014 controls | Polymorphisms in various genes | MSI, CIMP, KRAS, TP53 mutations in CC | Variants of insulin-related genes are associated with CIMP and MSI-H CC, especially among aspirin users. | |

| [134] | Slattery | 2010 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1198 CC, 1987 controls | SMAD7 SNPs (rs4939827, rs12953717, rs4464148) | MSI, CIMP, KRAS, TP53 mutations in CC | SMAD7 SNPs were not differentially associated with CC risk by MSI, CIMP, KRAS or TP53 status. | |

| [135] | Slattery | 2010 | CCS | Rectal cancer | KPMCP-UT-MN. 750 rectal cancers, 1205 controls | Diet, physical activity, body size | CIMP, TP53 mutation, KRAS mutation in rectal cancer | Certain dietary factors and physical activity are associated with CIMP, TP53 mutation or KRAS mutation in rectal cancer. However, no comparison (CIMP+ vs. CIMP−; TP53 mutation vs. WT; KRAS mutation vs. WT) is performed. | |

| [136] | Slattery | 2010 | CCS | Rectal cancer | KPMCP-UT-MN. 750 rectal cancers, 1250 controls | Calcium, vitamin D, VDR genotypes | CIMP, TP53 mutation, KRAS mutation in rectal cancer | Vitamin D intake and certain VDR genotypes are associated with certain TP53 mutations in rectal cancer | |

| [137] | Slattery | 2010 | CCS | Rectal cancer | KPMCP-UT-MN. 337 rectal cancers, 1192 controls | Alcohol intake | CIMP, TP53 mutation, KRAS mutation in rectal cancer | Recent high beer consumption is associated with TP53 mutation in rectal cancer. However, no comparison (TP53 mutation vs. WT) is performed. | |

| [138] | Slattery | CCS | CRC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 794 CRC, 1956 controls | SNPs in metabolic signaling pathway genes (MTOR, PTEN, STK11, PRKAA1, PRKAG2, TSC1, TSC2, PIK3CA, AKT1) | CIMP, MSI, KRAS mutation, TP53 mutation in CRC | PRKAA1 SNP (rs461404) is inversely associated with CIMP, and PRKAA1 SNP rs13167906 is positively associated with CIMP. However, no comparison (CIMP+ vs. CIMP−; MSI-high vs. MSS; TP53 mutation vs. WT; KRAS mutation vs. WT) is performed. | ||

| [139] | Urlich | 2005 | CCS | CC | KPMCP-UT-MN. 1248 CC, 1972 controls | MTHFR SNPs | TP53, KRAS mutations in CC | MTHFR codon 222 SNP variant is inversely associated with G>A mutations at CpG sites in TP53 in CC. | |

| [140] | van den Donk | 2007 | CCS | CRA | POLIER study. 149 CRA, 286 controls | Various nutrients, MTHFR codon 222 SNP | Methylation in APC, CDKN2A (p16), p14, MLH1, MGMT, RASSF1A in CRC | Folate intake may increase risk of adenoma without promoter methylation. | |

| [145] | Wark | 2006 | CCS | CRA | 534 CRA, 709 controls | Smoking, various food and nutrients | KRAS mutation in CRA | Smoking may increase risk of KRAS-WT CRA, but not that of KRAS-mutated CRA. | |

| [151] | Yang | 2000 | CCS | CRC | 161 CRC, 191 controls | SERPINA1 (A1AT) SNP | smoking | MSI in CRC | SERPINA1 SNP variant and smoking may synergistically increase risk of MSI-H CRC. |

| Nested case-control study | |||||||||

| [142] | Van Guelpen | 2010 | Nested CCS (in PCS) | CRC | NSHDS. 190 CRC, 380 (?) controls | Plasma folate, vitamin B12, homocysteine; MTHFR SNPs | CIMP, MSI, BRAF mutation in CRC | MTHFR rs1801131 (codon 429) SNP variant may be associated with CIMP-negative CRC, but not with CIMP-high or CIMP-low CRC. | |

| Prospective cohort studies (PCS) | |||||||||

| [36] | Chan | 2007 | PCS | CRC | NHS, HPFS. 13,0274 participants, 636 CRC | Aspirin | PTGS2 (COX-2) expression in CRC | Aspirin is associated with decreased risk of PTGS2 (COX-2)-positive CRC, but not with PTGS2-negative CRC. | |

| [53] | English | 2008 | PCS | CRC | MCCS. 41528 participants, 582 CRC | Ethnicity (Anglo-Celtic vs. southern European origins) | CIMP, BRAF mutation in CRC | Southern European origin is associated with lower risk for CIMP+ or BRAF-mutated CRC, but not with risk for CIMP-negative or BRAF-wild-type CRC. | |

| [78] | Limsui | 2010 | PCS | CRC | IWHS. 37,399 participants, 540 CRC | Smoking | MSI, CIMP, BRAF mutation in CRC | Smoking increases risks of MSI-high cancer, CIMP-high cancer, and BRAF-mutated cancer, but not MSS-low/MSS, non-CIMP-high or BRAF-wild-type cancer. | |

| [117] | Schernhammer | 2008 | PCS | CC | NHS. 88,691 participants, 399 CC | Dietary one-carbon nutrients, alcohol | TP53 expression in CC | Folate intake decreases TP53-positive CC risk, but not TP53-negative CC risk. | |

| [118] | Schernhammer | 2008 | PCS | CC | NHS, HPFS. 136,062 participants, 669 CC | Dietary one-carbon nutrients, alcohol | MSI, KRAS mutation in CC | CC risk does not significantly differ by MSI or KRAS mutation status. | |

| [119] | Schernhammer | 2010 | PCS | CC | NHS, HPFS. 136,054 participants, 609 CC | Dietary one-carbon nutrients, alcohol | LINE-1 methylation level in CC | Folate intake decreases LINE-1 hypomethylated CC risk, but not LINE-1 hypermethylated CC risk. | |

| [148] | Wish | 2010 | PCS | CRC | 4337 at-risk first degree relatives of 552 index CRC patients in the Newfoundland Cancer Registry | MSI, BRAF mutation in CRC | CRC events in first degree relatives | Compared to family members of patients with MSS BRAF-wild-type CRC, family members of patients with MSI-high BRAF-mutated CRC and those with MSS BRAF-mutated CRC show higher risks of developing CRC. | |

Official gene and protein symbols are described in the HUGO-Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) website (www.genenames.org). Studies with less than 100 cases with tumor tissue data are not listed, except for studies on rarely examined exposures or outcome. Studies on etiologically well-known types (polyposis syndromes, hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease-associated CRC) are not listed.

Sample size is based on cases with available tumor tissue data.

Abbreviations: A1AT, alpha-1-antitrypsin; BMI, body mass index; CC, colon cancer; CCFR, Colon Cancer Family Registry; CCS, case-control study; CGH, comparative genomic hybridization; CI, confidence interval; CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype; COX-2, cyclooxygenase 2; CRA, colorectal adenoma; CRC, colorectal cancer; DMR, differentially methylated region; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study; HR, hazard ratio; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; IWHS, Iowa Women’s Health Study; KPMCP-UT-MN, Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program of Northern California, the state of Utah and the Twin City Metropolitan area of Minnesota (the M. Slattery group’s case-control study); LOH, loss of heterozygosity; MCCS, Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study; MECCS, Molecular Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Study; MSI, microsatellite instability; MSI-H, microsatellite instability-high; MSI-L, microsatellite instability-low; MSS, microsatellite stability; NCCCS, North Carolina Colon Cancer Study; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study; NLCS, The Netherlands Cohort Study; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; NSCCG, National Study of Colorectal Cancer Genetics (UK); NSHDS, Northern Sweden Health and Disease Study; OR, odds ratio; RR, incidence rate ratio; PCS, prospective cohort study; PTGS2, prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2; RCT, randomized, placebo-controlled trial; SEER, Surveillance Epidemiology, and End Results; SERPINA1, serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade A (alpha-1 antiproteinase, antitrypsin), member 1; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; WBFT, Wheat Bran Fiber Trial; WT, wild-type.

Recently, GWAS have identified a number of candidate susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer.[9, 10] Currently, a significant limitation in interpreting GWAS results is our limited understanding of the functional relevance of risk alleles identified by GWAS. As a promising future direction, a molecular pathologic epidemiology approach can be used to validate findings of GWAS in certain ways. First, if a candidate cancer susceptibility variant is hypothesized to regulate expression of a nearby gene, the relationship between the variant and gene expression in tumor tissue can be examined.[59] Second, if a candidate variant is hypothesized to cause a genetic or epigenetic alteration in a critical pathway, the relationship between the variant and tumoral molecular alterations in the particular pathway can be examined.[134] Specificity of the relationship between the variant and the tumor molecular alterations will provide additional evidence to support a causal effect of the putative cancer susceptibility allele.

Additional examples of studies and findings on three specific areas (energy balance, inflammation, and one-carbon metabolism) will be discussed in later sections because these have been particularly active areas of investigations.

Study Design in Molecular Pathologic Epidemiology

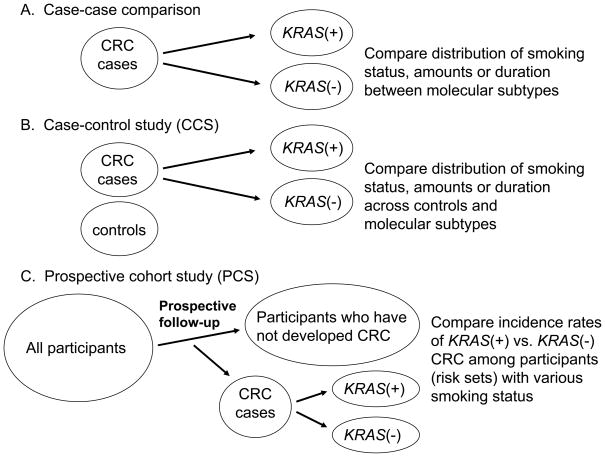

Figure 2 illustrates three basic approaches to investigate the relationship between an exposure (e.g., smoking) and a tumor molecular change (e.g., KRAS mutation). A fourth approach, an interventional cohort study (not illustrated in Figure 2) is a gold standard; however, to date no interventional molecular pathologic epidemiology data have been published.

Figure 2.

Comparison of a case-case study design (A), a case-control study design (B) and a prospective cohort study design (C). Smoking status is used as an example of an exposure variable, and KRAS mutation status in colorectal cancer as an outcome variable. See detailed explanations in text. CRC, colorectal cancer.

The first approach is a “case-case” approach (Figure 2A), where tumors are classified into subtypes according to a molecular feature, and then distributions of an exposure variable of interest among different subtypes are compared. For example, if it is hypothesized that smoking causes KRAS mutation, one may expect to observe that KRAS-mutated cancer patients contain a higher fraction of smokers than KRAS-wild-type cancer patients. A limitation of this approach is that it is not possible to obtain information on distribution of an exposure variable among the background population that has given rise to the cancer cases. Thus, the direction of any association cannot be determined; if there is a positive association between smoking and KRAS-mutated tumors (i.e., a negative association between smoking and KRAS-wild-type tumors), it is uncertain whether smoking protects against KRAS-wild-type tumors, or smoking causes KRAS-mutated tumors.

The second approach is a case-control study (Figure 2B), where non-cancer control subjects should ideally be randomly sampled from the background population that has given rise to the cancer cases. In traditional cancer epidemiology, distributions of an exposure of interest between cases and controls are compared. In molecular pathologic epidemiology, one can compare distributions of a given exposure between cancer cases with a specific molecular alteration (e.g., KRAS mutation), cancer cases without the alteration, and controls. If the exposure has caused the particular alteration, it is expected to see a higher fraction of exposed individuals among cancer cases with the alteration but not among cancer cases without the alteration, compared to controls. Nevertheless, case-control approaches in molecular pathologic epidemiology face the same inherent limitations of traditional case-control studies. Such caveats include recall bias, differential selection bias between cases and controls, among others. One advantage of a case-control design over a prospective cohort design is its relative ease to recruit a large number of colorectal cancer cases. Important examples of case-control studies include Colon Cancer Family Registry (CCFR), [26, 34, 35, 39, 56, 66, 76, 77, 79, 80, 106, 107, 154] a population-based case-control study of colorectal cancer by Slattery et al., [41–45, 113–115, 123–139, 155, 156] and the Molecular Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Study (MECCS) in northern Israel.[59, 110, 111, 157–159]

The third approach is a prospective cohort study (Figure 2C), which is less prone to potential bias related to case-case and case-control designs. A nested case-control design, a case-case design within a prospective cohort study, and a case-cohort design[160] are derivatives of prospective cohort studies. In molecular pathologic epidemiology, investigators examine the incidence rates of cancer with a specific alteration (e.g., KRAS mutation) in exposed vs. unexposed individuals, as well as the incidence rates of cancer without the specific alteration in exposed vs. unexposed individuals. If the exposure causes the particular alteration, one would expect to see a higher incidence rate of cancer with the alteration in exposed individuals than in unexposed individuals, and similar incidence rates of cancer without the alteration between the exposed and unexposed groups. In molecular pathologic epidemiology of colorectal cancer, to date, seven prospective cohort studies have published substantial data: European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC), [89, 103, 161–164] the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS), [2, 18–25, 36, 61, 65, 72, 91–101, 118, 119, 121] the Iowa Women’s Health Study (IWHS), [78, 165, 166] the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study (MCCS), [53, 167–169] the Netherlands Cohort Study (NLCS), [28–33, 46–48, 64, 82–84, 141, 144, 146, 147] the Northern Sweden Health and Disease Study (NSHDS), [142, 170, 171] and the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS).[2, 18–25, 36, 61, 65, 72, 91–101, 117–119, 121, 172] Prospective cohort studies require substantial amounts of participants, follow-up time and funding support, and substantial efforts of researchers and other personnel. Therefore, judicious utilization of the existing resource of prospective cohort studies is a cost effective approach.

Interactive Effect of Exposure and Tumoral Feature on Tumor Aggressiveness: New Direction of Molecular Pathologic Epidemiology

As a new direction of molecular pathologic epidemiology, our group has started examining how lifestyle or genetic factors interact with tumor molecular features to influence tumor cell behavior (prognosis or clinical outcome). Table 2 lists studies on interactive prognostic effects of lifestyle or genetic factors and tumoral features in colorectal cancer.[2, 18–21, 57, 72, 92, 93, 95–101, 173–178] In traditional molecular pathology, investigators examine tumoral molecular characteristics to better predict prognosis and response to specific treatments.[11] In addition to tumoral molecular features, lifestyle, environmental or genetic factors likely influence tumor cell behavior through the tumor microenvironment. Lifestyle factors (e.g., physical activity or smoking) or genetic factors (e.g., SNPs or family history) have been shown to influence clinical outcome of colorectal cancer patients.[168, 179–185] To better understand how a certain lifestyle, environmental or genetic factor influences tumor cell behavior, it is of interest to examine interactive prognostic effects of the lifestyle, environmental or genetic factor and tumoral molecular features. If a particular exposure is associated with worse outcome only among patients with a specific tumoral molecular change, but not among those without the molecular change, this provides evidence that the exposure factor might influence tumor aggressiveness through that molecular change or pathway. We will discuss specific examples in the following sections.

Table 2.

Molecular pathologic epidemiology studies to examine interactive prognostic effects of lifestyle or other etiologic factors and tumoral somatic changes in colorectal cancer.

| Ref. | First author | Year | Study design | Tissue specimens | Study cohort, sample sizes (N)* and notes | Tumoral feature | Hypothetical potential effect modifiers | Exploratory potential effect modifiers | Clinical outcome (number of events) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [18] | Baba | 2009 | PCS | CRC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 598 CRC | CDX2 expression in CRC | Sex, age, BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, CIN, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, CDKN1A (p21), CCND1, CTNNB1, PTGS2 (COX-2) | CRC-specific survival (156 events), overall survival (255 events) | Loss of CDX2 expression is associated with poor prognosis among patients with family history of CRC, but not those without family history of CRC. | |

| [19] | Baba | 2009 | PCS | CRC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 487 CRC | AURKA (Aurora-A) expression in CRC | Sex, age, BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, CIN, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, CDKN1A (p21), CCND1, CTNNB1, PTGS2 (COX-2), FASN | CRC-specific survival (124 events), overall survival (216 events) | AURKA expression in CRC is not associated with prognosis and there is no interaction between AURKA and any of the covariates. | |

| [20] | Baba | 2010 | PCS | CRC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 731 CRC | HIF1A, EPAS1 (HIF-2A) expression in CRC | Sex, age, BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, PTGS2 (COX-2) | CRC-specific survival (221 events), overall survival (344 events) | HIF1A expression in CRC is associated with poor prognosis, and its prognostic effect is consistent across any stratum of the covariates. EPAS1 (HIF-2A) expression in CRC is not associated with prognosis and there is no interaction between EPAS1 and any of the covariates. | |

| [21] | Baba | 2010 | PCS | CRC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 491 CRC | PTGER2 (prostaglandin EP2 receptor) expression in CRC | MSI, PTGS2 (COX-2) in CRC | Sex, age, BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, CTNNB1 | CRC-specific survival (139 events), overall survival (235 events) | PTGER2 expression in CRC is not associated with prognosis, and there is no interaction between PTGER2 and any of the covariates. |

| [23] | Baba | 2010 | PCS | CRC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 1033 CRC | IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation in CRC | Sex, age, BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation | CRC-specific survival (292 events), overall survival (494 events) | IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation in CRC is associated with poor prognosis, and there is no interaction between IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation and any of the covariates. | |

| [24] | Baba | 2010 | PCS | CRC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 718 CRC | Phosphorylated PRKA (AMPK) expression in CRC | Phosphorylated MAPK3/1 (ERK) expression in CRC | Sex, age, BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, FASN | CRC-specific survival (194 events), overall survival (306 events) | There is a significant interactive prognostic effect between p-PRKA (p-AMPK) and p-MAPK3/1 in CRC. p-PRKA expression is associated with good prognosis in p-MAPK3/1-positive cases, but not in p-MAPK3/1-negative cases. |

| [25] | Baba | 2010 | PCS | CRC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 717 CRC | Phosphorylated AKT expression in CRC | PIK3CA mutation in CRC | Sex, age, BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF mutation, expression of TP53, FASN | CRC-specific survival (210 events), overall survival (341 events) | p-AKT expression in CRC is associated with good prognosis, and there is no interaction between p-AKT and any of the covariates. |

| [173] | Chan | 2009 | PCS | CRC (stage I–III) | NHS, HPFS. 459 CRC | PTGS2 (COX-2) expression in CRC | Aspirin use (post-diagnosis) | CRC-specific survival (65 events), overall survival (167 events) | Aspirin decreases mortality of patients with PTGS2 (COX-2)-positive CRC, but not those with PTGS2-negative CRC. | |

| [57] | Fierstein | 2010 | PCS | CRC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 452 CRC | CDK8 expression in CRC | CTNNB1 in CRC | Sex, age, BMI (prediagnosis), tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, CDKN1A (p21), CDKN1B (p27), CCND1, PTGS2 (COX-2), FASN | CRC-specific survival (116 events), overall survival (202 events) | CDK8 expression in CC is associated with poor prognosis and there is no interaction between CDK8 and any of the covariates. |

| [72] | Kure | 2009 | PCS | CRC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 599 CRC | VDR expression in CRC | Sex, age, BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, CTNNB1, CDKN1A (p21), PTGS2 (COX-2) | CRC-specific survival (158 events), overall survival (260 events) | VDR expression in CRC is not associated with prognosis and there is no interaction between VDR and any of the covariates. | |

| [174] | Meyerhardt | 2009 | PCS | CC (stage I–III) | NHS, HPFS. 484 CRC | KRAS, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, CDKN1A (p21), CDKN1B (p27), FASN | Physical activity (post-diagnosis) | CC-specific survival (50 events), overall survival (152 events) | Beneficial prognostic effect of physical activity may be limited to patients with CDKN1B (p27) nuclear+ CC. | |

| [92] | Nosho | 2009 | PCS | CRC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 456 CRC | SIRT1 expression in CRC | BMI (pre-diagnosis) | Sex, age, family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, CTNNB1, FASN, PTGS2 (COX-2) | CRC-specific survival (116 events), overall survival (200 events) | SIRT1 expression in CRC is not associated with prognosis and there is no interaction between SIRT1 and any of the covariates. |

| [93] | Nosho | 2009 | PCS | CRC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 708 CRC | JC virus T antigen expression in CRC | Sex, age, BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, CTNNB1, FASN, PTGS2 (COX-2) | CRC-specific survival (182 events), overall survival (300 events) | JC virus T antigen expression in CRC is not associated with prognosis and there is no interaction between JC virus T antigen and any of the covariates. | |

| [175] | Nosho | 2009 | PCS | CRC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 733 CRC | DNMT3B expression in CRC | CIMP in CRC | Sex, age, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, CTNNB1 | CRC-specific survival (191 events), overall survival (313 events) | DNMT3B expression in CRC is not associated with prognosis and there is no interaction between DNMT3B and any of the covariates. |

| [2] | Ogino | 2008 | PCS | CC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 647 CC | FASN expression in CC | BMI (pre-diagnosis) | Sex, age, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, KRAS, BRAF mutation, TP53 expression | CC-specific survival (160 events), overall survival (279 events) | High prediagnosis BMI increases mortality of patients with FASN+ CC, but not those with FASN-negative CC. Beneficial prognostic effect of FASN+ is limited to patients with non-obese prediagnosis BMI. |

| [176] | Ogino | 2008 | PCS | CC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 662 CC | PTGS2 (COX-2) expression in CC | TP53 expression, MSI in CRC | Sex, age, tumor location, stage, grade, CIMP, KRAS, BRAF mutation | CC-specific survival (163 events), overall survival (283 events) | The adverse prognostic effect of PTGS2 (COX-2) is especially apparent in TP53-negative CC. |

| [177] | Ogino | 2008 | PCS | CC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 643 CC | LINE-1 methylation in CC | Sex, age, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, TP53 expression, KRAS, BRAF mutation | CC-specific survival (160 events), overall survival (276 events) | The adverse prognostic effect of LINE-1 hypomethylation is consistent across any stratum of potential effect modifiers. | |

| [95] | Ogino | 2009 | PCS | CRC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 470 CRC | PPARG expression in CRC | BMI (pre-diagnosis) | Sex, age, family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, CDKN1A (p21), CDKN1B (p27), CCND1, FASN, PTGS2 (COX-2), CTNNB1 | CRC-specific survival (118 events), overall survival (199 events) | PPARG expression is associated with good prognosis, and its effect is not modified by any of the covariates. |

| [96] | Ogino | 2009 | PCS | CRC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 546 CRC | STMN1 expression in CRC | BMI (pre-diagnosis) | Sex, age, family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, CDKN1A (p21), CDKN1B (p27), CCND1, FASN, PTGS2 (COX-2) | CRC-specific survival (147 events), overall survival (236 events) | Obesity (prediagnosis) increases mortality of patients with STMN1+ CRC, but not those with STMN1-negative CRC. The beneficial prognostic effect of STMN1+ is limited to patients with non-obese prediagnosis BMI. |

| [97] | Ogino | 2009 | PCS | CC (stage I–III) | NHS, HPFS. 450 CC | PIK3CA mutation in CC | BMI (pre-diagnosis), KRAS mutation in CRC | Sex, age, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, BRAF, expression of TP53 | CC-specific survival (66 events), overall survival (152 events) | PIK3CA mutation in CC is associated with poor prognosis, and its adverse effect may be limited to patients with KRAS-WT tumors. |

| [178] | Ogino | 2009 | CC (stage III) | Inter-group trial CALGB 89803. 508 CC | KRAS mutation in CC | Sex, age, BMI, tumor location, stage, performance status, clinical bowel obstruction, bowel perforation, treatment arm, MSI in CC. | Disease-free survival (196 events), recurrence-free survival (180 events), overall survival (149 events) | KRAS mutation is not associated with clinical outcome. There is no interaction between KRAS and any of the covariates. | ||

| [98] | Ogino | 2009 | PCS | CC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 630 CC | CDKN1B (p27) localization in CC | BMI (pre-diagnosis) | Sex, age, family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, CDKN1A (p21), CCND1, CTNNB1 (β-catenin), FASN, PTGS2 (COX-2) | CC-specific survival (160 events), overall survival (272 events) | Obesity (prediagnosis) increases mortality of patients with CDKN1B (p27) nuclear+ CC, but not those with CDKN1B-altered CC. The beneficial prognostic effect of CDKN1B alteration is limited to obese patients (prediagnosis). |

| [99] | Ogino | 2009 | PCS | CC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 647 CC | CDKN1A (p21) expression in CC | BMI (pre-diagnosis) | Sex, age, family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutation, expression of TP53, CCND1 | CC-specific survival (162 events), overall survival (279 events) | Obesity (prediagnosis) increases mortality of patients with CDKN1A (p21) expressing CC, but not those with CDKN1A-lost CC. CDKN1A loss is associated with good prognosis in patients 60 years old or older, but with poor prognosis in patients younger than 60 years. |

| [100] | Ogino | 2009 | PCS | CC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 602 CC | CCND1 (cyclin D1) expression in CC | MSI in CRC | Sex, age, BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, CIMP, KRAS, BRAF, mutation, expression of TP53, CDKN1A, CDKN1B, PTGS2 (COX-2), FASN | CC-specific survival (153 events), overall survival (259 events) | The beneficial prognostic effect of CCND1 expression in CC may be limited to MSI-low/MSS CC. |

| [101] | Ogino | 2009 | PCS | CC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 532 CRC | 18q LOH in CRC | Sex, age, BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, mutation, expression of TP53, CTNNB1, JC virus T antigen | CRC-specific survival (155 events), overall survival (239 events) | 18q LOH in CRC is not associated with prognosis. There is no interaction between 18q LOH and any of the covariates. | |

| [121] | Shima | 2010 | PCS | CRC (stage I–IV) | NHS, HPFS. 902 CRC | CDKN2A (p16) promoter methylation, loss of CDKN2A | Sex, age, BMI (prediagnosis), family history of CRC, tumor location, stage, grade, MSI, CIMP, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, mutation, expression of TP53, CDKN1A, CDKN1B, CCND1, CTNNB1, PTGS2, FASN. | CRC-specific survival (235 events), overall survival (409 events) | CDKN2A promoter methylation (or loss of expression) in CRC is not associated with prognosis. There is no interaction between CDKN2A and any of the covariates. |

Only studies with >300 tumor cases (generally with >100 events) are listed. To examine interactions with adequate statistical power, a sample size of at least 300 cases is necessary.

Official gene and protein symbols are described in the HUGO-Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) website (www.genenames.org).

Sample size is based on tumor tissue data available cases.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CALGB, Cancer and Leukemia Group B; CC, colon cancer; CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype; CIN, chromosomal instability; COX-2, cyclooxygenase 2; CRC, colorectal cancer; DMR, differentially methylated region; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study; HR, hazard ratio; LOH, loss of heterozygosity; MSI, microsatellite instability; MSI-H, microsatellite instability-high; MSI-L, microsatellite instability-low; MSS, microsatellite stability; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study; NLCS, The Netherlands Cohort Study; PCS, prospective cohort study; PTGS2, prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2; WT, wild-type.

Interactive Prognostic Effects of Obesity, Physical Activity and Tumoral Changes

Studies have shown that obesity is associated with worse survival of colon cancer patients.[168, 186–189] However, how obesity affects clinical outcome of cancer patients remains largely unknown. In 2008, our group started a new direction of molecular pathologic epidemiology, to examine an interactive prognostic effect of obesity (prediagnosis body mass index, BMI) and FASN (fatty acid synthase) expression in colon cancer.[2] We found that the adverse prognostic effect of obesity was present in patients with FASN-positive colon cancers, but not in patients with FASN-negative colon cancers.[2] These data suggest that excessive energy present in obese patients may contribute to growth and proliferation of tumor cells with FASN activation.[2] This study has opened new opportunities for investigating how lifestyle factors affect tumor cell behavior through cellular molecules. In traditional epidemiology, investigators examine the relationship between an exposure factor (e.g., obesity) and survival of cancer patients regardless of tumor molecular subtype; thus, mechanistic hypotheses remain speculative. For example, it is hypothesized that obesity increases tumor aggressiveness potentially through a certain cellular molecule such as FASN. Without analysis of FASN in tumor, the hypothesis still remains speculative. In molecular pathologic epidemiology, we can specifically test the hypothesis by examining the relations between obesity and patient survival in tumor FASN-positive cases and between obesity and patient survival in tumor FASN-negative cases.[2] If the hypothesis is true, we expect to observe the significant obesity/survival relationship in FASN-positive cases, but not in FASN-negative cases.[2]

Our subsequent investigations have found that a number of other tumor molecular changes interact with prediagnosis BMI to modify tumor aggressiveness.[96, 98, 99] Those tumor changes include STMN1 expression, [96] CDKN1A (p21) expression, [99] and CDKN1B (p27) cellular localization, [98] all of which have been linked to energy balance and related signal transduction pathways.[190–193] In addition, our analysis on interactive prognostic effects of physical activity and tumor markers have revealed that postdiagnosis physical activity is beneficial only in patients with CDKN1B-nuclear-positive colon cancers, but not in patients with CDKN1B-altered or lost colon cancers.[174] These results collectively provide evidence for tumor-host interactions (energy balance status and tumor molecular alterations) that influence tumor cell behavior.

Inflammation and Carcinogenesis

Epidemiological studies have shown that regular use of aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) is associated with decreased risks of colorectal cancer and adenomas.[194–203] Randomized trials have confirmed that regular use of aspirin[204–206] or other inhibitors of PTGS2 (prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2, cyclooxygenase-2, COX-2)[207–209] decreases risk of developing colorectal adenomas. Experimental evidence suggests an important role of PTGS2 in colorectal carcinogenesis.[210–212] Thus, it is hypothesized that PTGS2 (COX-2) inhibitors may prevent colorectal tumor through inhibition of PTGS2. Molecular pathologic epidemiology research has provided further insights on mechanisms of cancer preventive effect of PTGS2 inhibition. Utilizing the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS), we found that regular aspirin use decreases risk of cancers with PTGS2 (COX-2) overexpression, but not that of cancers without PTGS2 overexpression.[36] This specific inverse association between aspirin use and incidence of PTGS2-positive cancer provides further evidence for the carcinogenic role of PTGS2 (COX-2), and for the role of PTGS2 (COX-2) inhibitors in cancer prevention.

We have also shown that PTGS2 (COX-2) overexpression is associated with aggressive tumor behavior, [176] and that regular aspirin use after colorectal cancer diagnosis significantly decreases mortality in patients with PTGS2-positive cancers, but not in patients with PTGS2-negative cancers.[173] This specificity of the relation between aspirin use and low mortality in PTGS2-expressing cases provides additional evidence for the role of PTGS2 inhibition in prevention of cancer progression.

One-Carbon Metabolism, Germline Variants, and Somatic Epigenetic Changes

Colorectal cancer is a complex disease resulting from both genetic and epigenetic alterations, including abnormal DNA methylation patterns.[213, 214] DNA hypomethylation at LINE-1 repetitive elements has been associated with poor prognosis in colon cancer.[177] LINE-1 hypomethylation may provide alternative promoter activation, [215] and contribute to non-coding RNA expression that regulates expression of many genes.[216, 217] Retrotransposons activated by DNA hypomethylation may transpose themselves throughout the genome, leading to gene disruptions[218] and chromosomal instability (CIN).[219, 220] In addition, there exists a specific tumor phenotype – the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), characterized by propensity for widespread CpG island hypermethylation.[221] High degree of CIMP (CIMP-high) is a distinct phenotype, [5, 15, 222–225] and the most common cause of microsatellite instability (MSI) in colorectal cancer through epigenetic inactivation of a mismatch repair gene MLH1.[226–230] Independent of MSI, CIMP-high is associated with older age, female gender, proximal tumor location, [228, 231, 232] high tumor grade, signet ring cells, [233] BRAF mutation, [228, 231, 232] wild-type TP53, [228, 234] inactive PTGS2 (COX-2), [234] inactive CTNNB1 (β-catenin), [235] loss of CDKN1B (p27), [236] high-level LINE-1 methylation, [231, 237] stable chromosomes, [238, 239] and expression of DNMT3B, [175] CDKN1A (p21), [240] and SIRT1.[92] Thus, CIMP status is a potential confounder for many locus-specific tumor variables.[5] Moreover, the relationship between KRAS mutation and another type of CIMP {“CIMP-low”, [5, 231, 241–245] “CIMP2”, [246] and “intermediate-methylation epigenotype”[247]} has been demonstrated. Importantly, different CIMP subtypes appear to show different locus-specific methylation patterns.[231, 244, 246–248] Accumulating evidence suggests that CIMP-high colorectal cancers arise through the “serrated pathway”, [249–259] which has substantial implications in studies on colorectal polyps and adenomas, because of potential differences in detection rates, removal rates and natural histories between conventional and serrated precursor lesions. The elucidation of mechanisms of epigenetic aberrations will improve our understanding of the carcinogenic process.