Abstract

The aim of this study was an in-depth investigation of the change process experienced by patients undergoing bariatric surgery. A prospective interview study was performed prior to as well as 1 and 2 years after surgery. Data analyses of the transcribed interviews were performed by means of the Grounded Theory method. A core category was identified: Wishing for deburdening through a sustainable control over eating and weight, comprising three related categories: hoping for deburdening and control through surgery, feeling deburdened and practising control through physical restriction, and feeling deburdened and trying to maintain control by own willpower. Before surgery, the participants experienced little or no control in relation to food and eating and hoped that the bariatric procedure would be the first brick in the building of a foundation that would lead to control in this area. The control thus achieved in turn affected the participants' relationship to themselves, their roles in society, and the family as well as to health care. One year after surgery they reported established routines regarding eating as well as higher self-esteem due to weight loss. In family and society they set limits and in relation to health care staff they felt their concern and reported satisfaction with the surgery. After 2 years, fear of weight gain resurfaced and their self-image was modified to be more realistic. They were no longer totally self-confident about their condition, but realised that maintaining control was a matter of struggle to obtaining a foundation of sustainable control. Between 1 and 2 years after surgery, the physical control mechanism over eating habits started to more or less fade for all participants. An implication is that when this occurs, health care professionals need to provide interventions that help to maintain the weight loss in order to achieve a good long-term outcome.

Keywords: Morbid obesity, surgery, prospective interview study, inside and outside perspective, feeling of control, eating behaviour, grounded theory

Introduction

Obesity leads to reduced life expectancy and is one of the greatest threats to well-being and health around the world today. The impact on health caused by obesity is large, with increased risk of co-morbidities such as heart-disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, and most forms of cancer. Obesity is also associated with psychological and social problems such as depression, interpersonal problems, low social adjustment, social isolation, and occupational problems as well as low quality of life (QoL; Van Hout et al., 2003). According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), approximately 1.6 billion adults globally are overweight (BMI >25 kg/m2), of whom at least 400 million are obese (BMI >30 kg/m2; WHO, 2010), see Table I for further BMI classifications.

Table I.

BMI classification by the WHO.

| Classification | BMI (kg/m2) |

|---|---|

| Normal range | 18.50–24.99 |

| Overweight | ≥25.00 |

| Pre-obese | 25.00–29.99 |

| Obese | ≥30.00 |

| Obese class I | 30.00–34.99 |

| Obese class II | 35.00–39.99 |

| Obese class III | ≥40.00 |

The only successful treatment for morbid obesity (BMI >40 kg/m2) is weight loss surgery, more commonly known as bariatric surgery. In Sweden, 1900 bariatric operations were performed in public hospitals during 2007, and an estimation for the coming years indicated that 2500–3000 operations per year would be carried out in 2008/2009. Considering that 175,000 Swedes have a BMI that requires surgery, this is not enough. A conservative estimate indicated the need for around 10–15,000 procedures per year in Sweden (Näslund et al., 2009).

Both the effects and the side-effects of bariatric procedures are well documented. For the majority of patients, this type of surgery results in long-term weight loss, a healthier life, and higher QoL (Karlsson, Taft, Ryden, Sjostrom, & Sullivan, 2007; Sjostrom et al., 2004). However, some patients are unable to maintain their weight loss over time, resulting in a negative long-term outcome regarding their mental and physical well-being (Hsu et al., 1998; Karlsson et al., 2007). The initial weight loss is achieved by surgically reducing, removing, or resecting a smaller or larger part of the stomach, with or without re-routing the small intestines. One side-effect of some bariatric procedures can be the so called “dumping syndrome” that leads to symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, weakness, and faintness and is caused by intake of food with a high calorie density. Dumping is often described as an adverse effect of surgery that makes patients avoid unhealthy food (Blackwood, 2004). So called hunger and satiation hormones (gut hormones) also influence the weight loss after surgery (le Roux et al., 2007). In conclusion, the medical aspect (e.g., co-morbidities, physical long-term outcome) of bariatric surgery is well documented. However, to our knowledge, very few studies are based on patients' own experience of life adjustments before and after surgery. Earlier qualitative research described how patients experienced major life changes after surgery. Such changes might include: a feeling of being in control in various ways (e.g., over food intake), having a higher sense of self-esteem, a better structure in life, and an overall feeling of empowerment (Bocchieri, Meana, & Fisher, 2002; Earvolino-Ramirez, 2008; Glinski, Wetzler, & Goodman, 2001; Ogden, Clementi, & Aylwin, 2006; Ogden, Clementi, Aylwin, & Patel, 2005; Wysoker, 2005).

From both a scientific and a clinical perspective, we know that bariatric surgery results in a long-term weight loss for many but not all patients and that a process of major life changes starts for the obese person after the procedure. However, we do not know how this process of change actually works and how it continues over time. Therefore, we found it very important to investigate this process of change, as it would enable us to provide continued care with a successful long-term outcome and not only view surgery as a selective measure. The key research question was: What is the main concern of the participants before bariatric surgery, as well as 1 and 2 years after surgery and how are they trying to resolve it? The present study was designed as a prospective interview study, which gave us the opportunity to determine what type of and at what point in time care interventions are needed.

Method

Study group

The study group consisted of 16 members before as well as 1 year after surgery and 11 took part 2 years after surgery (see detailed characteristics in Table II). The present study was part of a larger investigation designed to examine the outcome of two different types of surgery techniques in patients suffering from super obesity (BMI 50–60 kg/m2; Sovik et al., 2009). Study group selection was based on gender, age, and BMI in order to ensure a broad range of experience.

Table II.

Characteristics of the study participants who underwent bariatric surgery.

| Before surgery (n=16) | One year after surgery (n=16) | Two years after surgery (n=11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age; mean years (range) | 36.8 (24–44) | — | — |

| BMI; mean BMI, kg/m2 | 56.0 | 35.5 | 34.8 |

| Women (%) | 12 (75) | 12 (75) | 9 (82) |

| Men (%) | 4 (25) | 4 (25) | 2 (18) |

| Married or co-habiting (%) | 12 (75) | 13 (81) | 10 (91) |

| Single (%) | 4 (25) | 3 (19) | 1 (9) |

| Gainfully employed (%) | 10 (63) | 11 (69) | 8 (73)* |

| Student (%) | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | 1 (9) |

| Disability pension/sick leave (%) | 5 (31) | 4 (25) | 2 (18) |

Legend:

Two out of eight participants who were gainfully employed were on parental leave.

Data collection and data analysis

Our main concern was the wish to understand the process of change after bariatric surgery. Thus, the starting point was: What is the main concern before as well as after surgery and how do the participants deal with this? Data were collected by interviews lasting between 20 min and 1.5 h, using an interview guide consisting of questions such as: “What do you expect from surgery?” and “How does obesity affect you today?” And after surgery: “Please describe your life today.” Before surgery it was difficult to obtain comprehensive answers even to encouraging follow-up questions such as: Ok, interesting, tell me more. Can you please describe that feeling more in depth? and so on. To discover changes over time, we used the same type of questions 1 year after surgery, at which stage the answers were rich and often interpreted without the need for probing questions. To render the data conceptual, we followed Charmaz's (2006) recommendations and started with an open-coding phase, coding line-by-line and impartially searching for intelligible words and phrases that indicated important categories, qualities, or connections. In this regard, we increased our memo writing including thoughts and questions that emerged during the initial coding. We continued with focus coding, in order to determine whether the codes that emerged during the open-coding process were adequate throughout the data. This coding was guided by three questions: What is the main concern, Which are the consequences from the main concern, and Which strategies are used to deal with the main concern? The reason for this coding was to grasp the consequences through the eyes of the participants. Simultaneously, more “advanced” memos were written about how the categories and their relationships could be combined over time. Several new research questions arose during this analysis phase; that is, What do they actually do to deal with the obesity or weight loss? or Does a balanced eating behaviour lead to changes in family life or social life? The data revealed how social processes were affected by obesity and later the weight loss, what participants hoped for and expected from surgery, and also how the process of change occurred over time. This process formed the basis of our next data collection 2 years after surgery, giving us the opportunity to ask questions about how earlier expectations had been fulfilled, followed by questions such as: Can you please describe your relationship to food? How do you view yourself today? Can you please elaborate about your role in the family/society/health care? The rich narratives continued 2 years after surgery and led to saturation after 11 interviews. At this point we believed that the key question was answered. Saturation and the wish to complete the study within a reasonable time allowed us to finish data collection and continue with the analysis process. More recent data strengthened and confirmed our categories from previous data, although the content of the subcategories differed over time.

Ethical aspects

Before inclusion, the participants were informed verbally and in writing about the study design, voluntariness, confidentiality, and that they could withdraw without consequences for further care at any time during the 2 year follow-up. Written informed consent was obtained. Before conducting the interview after 1 and 2 years, respectively, we verbally repeated the information about voluntariness and that they could withdraw at any time. Preparations were made if further apprehending would be necessary in connection with the interviews. Two participants were referred to our social counsellor after surgery. The study was approved by the human research ethics committee at Gothenburg University, No. S 688-02.

Results

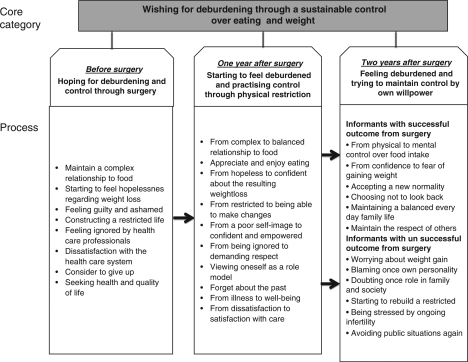

A core category, “wishing for deburdening through a sustainable control over eating and weight”, was identified and illuminates the main concern of all the participants when they approached and went through bariatric surgery. The hope for sustainable control was the main reason for surgery. The core category was related to all three categories that illuminated parts of the main concern at different times after surgery and involved all of the participants. It described the steps in the process of change from being burdened by obesity before surgery and hoping for control, to feeling deburdened by surgery one year afterwards, and practising control and a condition involving adjustment and a balanced relationship to food after 2 years, however starting to doubt the control. The basic driving force in the process seemed to be the wish for sustainable control over eating and weight, in turn leading to and resulting in control in several other areas of life. One main strategy throughout the whole process for obtaining and maintaining control was by reflecting on their previous condition of being morbidly obese. Each category was divided into subcategories, the content of which differed in some areas between patients with a successful weight loss and patients who did not succeed as expected to loose weight, as can be seen in Figure 1. In the text, the subcategories are presented in italics and represent strategies of how the informants dealt with the main concern or consequences from the main concern.

Figure 1.

Illustrating the core category: wishing for deburdening through a sustainable control over eating and weight, comprising three related categories: hoping for deburdening and control through surgery, starting to feel deburdened and practising control through physical restriction, and feeling deburdened and trying to maintain control by own willpower. The process of change is illustrated over a period of 2 years by subcategories describing how the participants dealt with the main concern.

Hoping for deburdening and control through surgery

The main concern before surgery was that all participants were burdened by obesity due to a total loss of control regarding food intake. They constantly hoped for control and wished to obtain help to lose weight. All participants were well aware that their eating behaviour was the main cause of their obesity. They maintained a complex relationship to food and used the following keywords: how, why, and what, when describing their relationship to food both before and after surgery. Initially, uncontrolled eating behaviour including meals per day, portions sizes, and unhealthy food choices were often described. Some connected their eating with emotional states such as sadness, happiness, or obstinacy. Others explained how they actually experienced a total lack of interest in food itself. Instead, they ate in a sort of life-supporting way, involving large portions of uniform, nutrient-poor food once or twice a day. Several ignored their feeling of hunger during the daytime and avoided eating in public, at work, or in school. However, when at home, the obstructive feeling ceased and they started to eat in an uncontrolled manner, often without thinking. Afterwards, feelings of despair and sadness occurred. Many informants viewed their relationship to food as an abuse and some draw analogues to alcoholism.

I view this as an addiction. In the same way as alcoholism is an addiction, I am addicted to food. I eat when I'm sad, when I need comfort, when I celebrate or when I'm happy or hungry. Yes, that's my point of view.

This uncontrolled eating and weight situation resulted in a state where they started to feel hopelessness regarding weight loss. Loosing weight and regaining it again involving feelings of hopelessness was a common experience among the informants. They believed that the help of surgery only could stop the endless roller coaster of unsuccessful dieting

So, I've tried all other ways, and I had so many backlashes and I wanted something more permanent. So I thought that surgery was the only thing.

The informants thought of and described their bodies in a negative and dissatisfied way. Often they avoided mirrors and they seldom used a scale to avoid the fact of their looks. They felt hatred and disgust towards themselves. These feelings were empowered when getting evil and defamatory comments from people around them.

I have like no idea, like I haven't measured my weight for over a year, until today then, and today I shut my eyes.

Being obese often leads to a personality change reported by the informants. They felt guilty and ashamed about themselves. A self-image built on laziness, shame, self-contempt, and enervating feelings were often described by the participants. These feelings were accusations against their own personality for being less valuable persons compared to others and were seldom directly connected with the burden of being obese. Feelings of being looked down on by others were common, as was feeling rejected in various situations (e.g., on the employment market). They thought that others viewed them as victims of their obesity, trapped in a large body and hardly able to do anything. These deprecatory feelings and those they perceived that others had of them caused many of the participants to enter into a state in which they felt unable to influence their life situation.

Everybody stares and have an opinion about you. I actually don't care what they think. It's more what I think of myself. Then I feel sorrier for people who need to look at me.

A majority of the informants constructed a restricted life before surgery when it came to family, friends, and society. Living beside life and not playing an active part in one's family or in society was the main feeling of many of the participants. In order to cope with their everyday life they often needed help from family members, leading to feelings of dependency and helplessness. Within the group, dependency varied from help with personal hygiene to getting up from the sofa. Others had a permanently guilty conscience because family members had to take care of all household tasks such as shopping, cleaning, and doing the washing. Their role in the family and society was much affected by their obesity rather than their personality, which was not what they wanted.

[T]he children, soon they will be adults, but still you would like to have strength left for them as well. I often used to feel tired and grumpy, and I think that it was due to my weight. And even my sex life at home, I think it will improve.

Several of the participants were unemployed or on long-term sick leave and felt unwanted in society. Some narrated how they had lost job opportunities because the employer just did not want someone who was so obese. Feeling isolated was common and could be due to various factors. Not going to school or work led to isolation. On the other hand after a day at work, some of the participants reported feeling so tired that it was almost impossible to manage other activities, for example, going out with friends. Other reasons for isolation were fear or being tired of hurtful comments. A short walk was too demanding as was not knowing whether the restaurant chairs were wide enough to sit on. Being unable to find attractive clothes in their size bothered many and made them “stick out” in a negative way. They hoped that after surgery they would be able to shop in a regular store.

Today I feel that I have so many limitations. I would like to be able to go out with the dog. I have to plan my life and the number of metres, as I have to make sure that I don't walk too much. And if I'm going somewhere, I have to take it easy or otherwise I can do no more. I have to plan where I park the car, because I can't walk too far, I can't manage it.

The participants' experiences of health care can be divided into three areas: caring encounters, health perspective, and motive for surgery. The informants felt ignored by health care professionals. Receiving proper help (i.e., surgery) for their morbid obesity had often been a long and difficult journey. When seeking help at the local care centre, they encountered staff that had a serious lack of knowledge of how to treat morbidly obese persons. Several health care providers still thought that the only way was by means of conventional methods such as diet and exercise. This led to huge dissatisfaction with the health care system on the part of the participants, because they had undergone conventional treatment on several occasions with no effect at all. What ever other disease or illness they sought help for, they always were advised to loose weight in order to make all other physical or medical problems disappear.

The only answer they give me is that if I lose weight my back will be fine. That's my experience. And if I tell them that my arm is broken they say: lose weight and your arm will be fine. I have met that attitude both from physicians and other health care professionals.

When they finally obtained a referral to the hospital for surgery they had another unpleasant surprise in that the waiting time was at least 2 and in some cases up to 5 years. Some described that they considered to give up when they found out how long the waiting list was. Others narrated how they lost the little control they had in terms of restraining their eating. From a health perspective, obesity was often described as a feeling of ill health caused by fatigue and restrictions due to their size. Family members (e.g., mother or husband) often viewed the participants as unhealthier than they themselves experienced. At the same time, one of the main motives for surgery along with a control mechanism for eating was a desire to become healthier. Whether or not they suffered from co-morbidities, many stated that they were seeking health and quality of life since they were afraid of becoming ill and had a fear of death. This fear was mainly described by study participants who had children, as they feared not being there when their child was growing up. Another major health issue and motive for surgery for several of the women in our study was infertility.

In conclusion, a major part of choosing surgery and experiencing motivation for it was the feeling of loss of control and the huge burden caused by obesity. Many of the informants narrated that they desired a mechanism in their body to help them control their eating behaviour.

I need this superior person telling me what to do. I view the operation as a superior person, since the operation will make my bowel smaller, thus obliging me to eat less. It may sound strange, but somehow my stomach will set the limit. At present my stomach tells me to eat more and more. I won't have that after the operation.

Hoping to have a some quality of life involved the hope of getting out more from life itself, to get an energy catalyser with a more normal weight; that is, become more physically active and being able to keep or receive a job as well as becoming happier. Having a well-functioning social situation in the family, with friends, and playing an active part in the society was something that the informants were hoping to achieve with help from the surgery and the weight loss that was supposed to follow.

I expect to have less pain and that my stiffness will disappear. I expect to get better self-esteem; I expect to become even more social than I am today.

Starting to feel deburdened and practising control through physical restriction

During the first year after surgery, the relationship to food went from complex to balanced and totally transformed. Now the reason they ate mainly depended on their bodies' own physical signals, which sent out strong demands for meals several times a day with regular intervals in-between. Some also experienced dumping symptoms when eating the “wrong” type of food. If they ignored the bodily signals and skipped meals, symptoms such as nausea, fatigue, and annoyance appeared, which among other things led them to cease avoiding eating at work. Healthier food choices, both for meals and in-between meals, were the new reality with the food containing more vegetables, less gravy, and comprising smaller portions. Despite smaller and healthier portions, many described, with great joy, how for the first time for many years they felt satiation after a meal and how they now appreciated and enjoyed eating. The participants felt in control of their eating pattern.

The healthier choice of food was due to three factors: Firstly, food with a high calorie density could lead to strong negative physical responses such as irregular heartbeat, drop in blood pressure, diarrhoea, or just feeling very tired. Surprisingly, none of the participants described these symptoms as negative; on the contrary, they appreciated this strong bodily signal that made them avoid meals containing a high level of carbohydrates or fat. Secondly, several of the participants were now aware of what they actually ate; they often connected their choice of food with their new healthier life-style and weight loss. They also described a new found interest in food and cooking and how they had become more open-minded in terms of trying new and different types of food, for example more vegetarian dishes. And finally, the participants had a strong desire to never return to their previous situation. This controlled eating behaviour led to the long wished for weight loss without the sensation of dieting. The feeling of control and confidence in their relationship with food also strongly affected the other domains in life.

[B]efore I could skip meals and so, you know, skip breakfast, skip lunch and then when I came home, I was starving and just grabbed whatever was there, and I often chose unnecessary things such as chocolate wafer biscuits and whatever. And then I [am] very full and hyperactive due to the high sugar level and at 9 p.m. I did not have the energy to do anything, and would order a pizza or so, and that's why I weighed 150 kilo. It's a vicious circle. Nowadays if I miss breakfast I become furious, I sort of have to have food (laugh), I have to have lunch; I have to have fruit as a light meal. I eat mandarins all the time, even now and Clementines.

The informants went from hopeless to confident about the resulting weight loss. However, along with these positive feelings related to control and weight loss, there were often worries about regaining weight due to uncontrolled eating behaviour. Although most of the participants felt satisfied with the physical control over their food consumption, some would have preferred a stronger signal (e.g., more dumping) when choosing less healthy food or large portions. They were worried that a new normality would rapidly establish itself in relation to food, although some of the food chosen was healthier and 1 year after surgery they were able to eat a normal portion of food.

The first year after surgery was filled with feelings of, for example, energy, single-mindedness, and happiness. The previously described inability to influence themselves and those around them was now transformed into feelings of almost euphoric energy in terms of moving from being restricted to an ability to make changes. It was a time of reconstructing (more or less consciously) from a poor self-image to someone confident and empowered. When this improved self-image emerged, many looked back and could see how the obesity, and not their personality, was the cause of their previous negative self-image. They experienced that others viewed them as the person they actually were and not just as a poor obese body. Both pleasant and unpleasant feelings occurred when experiencing how people treated them with respect. In one way it was wonderful to be treated with respect, but at the same time they felt sad that people had previously been unable to see them as they really were. Another, less positive state was still feeling obese, despite having lost a great deal of weight.

It's how you look at yourself, you still think that you're big, and even if you hear many comments like oh, you are looking so good and so on, and of course it helps a great deal, but the image of myself when looking in the mirror is that my belly is still big and so, ah, I still think it's hard.

One year after surgery the passive role had changed to a very active one thanks to the feelings of confidence and empowerment. They now had plenty of energy to manage work or go back to studies and to be a complete family member. For some, all of a sudden one job was not enough. They got a second one, or switched careers, and a previously unemployed patient had been able to find work. Participants with children described how they enjoyed an active and happy relationship with each other. For example, the joy of being able to shop for clothes with their teenage daughters; they could find sizes for themselves and did not have to be afraid that their children would be ashamed of them. All children and teenagers probably did not totally appreciate their parent's new role, because the situation at home could become more educative and demanding than before.

And it's everything, joy and belief in the future, work and what I manage at work, there is just no comparison. Before it was just to get to work, to get out of the car, everything was a task, an effort and I often fell asleep before I got out of the car at home, you know I even fell asleep in the yard, my children found me there, because I could not manage any longer. And now when I get home its like, well now I shall do this and that and I have other activities besides my job, like evening courses, so there is no comparison.

None of the participants mentioned isolation anymore. They no longer had to plan for every move due to lack of vitality and their life became more “easy going.” For example, if friends phoned and asked if they wanted to go to the cinema, they had the energy to come along, and did not have to worry about fitting into the cinema seats. Being treated with respect in shops, restaurants, by passers-by on the street, and in some cases also within the family was now commonly reported. Perhaps this situation was partly due to the fact that the participants now have moved from being ignored to demanding respect from others. Before surgery many wished for a more “normal” appearance and being able to blend in and be more invisible in society. But now some viewed themselves as role models for other morbidly obese people and wanted to help them. In the same way as with self-image some preferred not to look back, as they realised how poor their life had been before, how their children had been ashamed of them, and how much they had been stigmatised by others, so now they tried to forget all about the past.

Life has become better and also my relationship with my wife and it couldn't be better (pause), it's a new beginning, a very short time has passed, but you can almost feel that (pause) the other life is history, it was just a dream, a nightmare or something.

One year after surgery, feelings of well-being and regained health due to weight loss resulted in great satisfaction. The participants began to feel deburdened, not only by weight loss but at many areas in life. For example, the participants were able to wake up without experiencing any bodily pain and were able to take a walk without aching back, feet, and knees. They viewed their health with a more open mind and compared with their situation before surgery they had moved from illness to well-being. Some reminded themselves of their pre-surgical condition as a strategy to keep up their motivation to maintain a healthier lifestyle (e.g., food intake and exercise). Overall, the narratives contained little about health issues at this point of the data collection. The participants had moved from dissatisfaction to satisfaction with care during their hospital stay as well as the three follow-up visits during the first year after discharge.

It's almost impossible to think, I can't really understand, sometimes you sort of look back, that's right, yes that is how it was, my God, it was so hard. You know when I arrive at a place I haven't been to for a long time, I think that the last time I didn't manage to walk that distance, and I didn't want to admit that to myself, but now, with the result in my hand, I realise how bad I actually felt, yes.

Feeling deburdened and trying to maintain control by own willpower

After 2 years, the process of change differed between those with a successful and unsuccessful outcome as shown in Figure 1. Depending on outcome, the participants handled the main concern differently. Two years after the bariatric procedure, the physically controlled system related to how, why, and what the participants ate had gradually changed from physical to mental control over food intake. Several still experienced a physical restraint characterised by feelings of satiation and dumping, but not to the same extent as the year before. Willpower to never return to obesity and uncontrolled eating helped the participants to restrain themselves. When it came to food choice, they consumed much healthier food compared to before surgery and, although the portion sizes had become larger compared to 1 year after surgery, they were still smaller than before. Several participants still felt a reduced craving for sweets and crisps. Their tastes changed, which meant that they avoided food such as sausages and burgers, which they had often consumed before surgery, as these no longer tasted good. Some participants worried about weight gain and felt sad when describing a loss of the physical and mental stop mechanism for overeating. Participants with good control over their food intake also described a move from confidence to fear of gaining weight, which thoughts often preoccupied them. The confident feeling of control that was present a year ago had now changed into a more doubtful state. This made the participants aware of how they had to strive to maintain what they had achieved so far in terms of weight loss as well as self-image, their role in the family and society, and their improved health.

I do eat more often, I think so at least, a bit more often than before. I don't eat the same things; since I started to work I have breakfast, lunch and dinner every day. But I don't eat a bag of crisps for supper, I don't eat a whole packet of biscuits, even if I would really like to sometimes.

At 2 years postoperatively, many of the positive feelings towards themselves from 1 year after surgery still remained but in a more balanced way, and they accepted a new normality. Within this new normality was also the consisted facilitative feeling of being allowed to be oneself. When this occurred, many repeated what they had said a year before, about how they chose not to look back at their life before surgery.

… I'm living this life now, and you become rather spoilt, you forget fairly fast, but I see photos for example, and that's not funny, you want it to be a closed chapter.

A few participants, all of whom had regained weight, reported that they had yet again started to view themselves in a more negative way. They blamed their own personality for being weak or lazy because of their inability to mentally control their eating habits and weight.

After 2 years they maintained a balanced everyday family life, built on permanence, participation, and established roles on the part of the informants as well as other family members. For some, this led to time, opportunity, and the urge to take part in or begin new projects in their spare time (e.g., courses, a small business, or singing in a choir). Participants who had previously been single had now started to look for a partner and gone on dates, something that they had considered impossible before surgery. In terms of society, many still talked about how they had become more confident and took a tougher attitude towards others. They did not adjust in a way that made them feel uncomfortable and were still very aware of maintaining the respect of others.

Before, I could stand and listen and chat for 2 h, but now I can't manage that anymore, I just end the conversation and that can be perceived as a bit cocky, I just do it to show that I've had enough.

Participants who regained weight or were still on sick leave or unemployed 2 years after surgery doubted their own role in the family and society. They narrated that the overall positive feeling they had experienced 1 year after surgery had now started to evaporate. This affected their relationship at home as once again they were unable to equally share household chores, and negative feelings arose between partners when the non-obese partner commented on increased food intake. From an outside perspective, the participants started to re build a restricted life and were unable to take part as a full member.

When 2 years had elapsed since surgery, many participants could not remember the last time they had felt sick, had a headache, or bodily pain.

I feel very well, I haven't needed any more medication for my rheumatism, and it feels wonderful.

Two out of four women who had been unable to become pregnant before surgery had now given birth to a child and for them that was the biggest benefit of surgery. They described their joy, not only of becoming pregnant, but also about how they could be active in their parenting role. The remaining two women, on the other hand, were very stressed by their ongoing infertility and described it as a major concern. They hoped for further weight loss that would lead to increased fertility or that they could obtain help with in vitro fertilisation if they achieved a BMI of 30 kg/m2.

One negative side effect after surgery was the surplus skin that became a big health and well-being problem for several of the participants. Once again, they were in need of health care, and it was very frustrating having to wait for the health care system to help them. Because of the embarrassment of the surplus skin, they avoided public situations again. These actions involved situations that they previously avoided because of their obesity, for example going to the beach with their family.

[Y]es, I have periods when I upset myself a lot about everything, and it's hard, you always have lumps of skin that bulge out under your arms. If you sleep on your belly at night, you get fungus or heat eczema, and you always have spots all over your stomach, so sometimes it's just too much and you cannot take any more. I just want to cut everything away, everything that is hanging out. Just cut it off, and sometimes I actually really miss, I mean I almost wish all the kilos back just to fill out the skin (pause), because it will never be totally perfect.

Discussion

Our main reason for choosing the Grounded Theory method with a prospective design and in-depth interview is that, according to Charmaz (2006), it provides a deeper understanding of the participants' lives compared to a structured and informal interview. Since we had a great interest in the inside perspective, we used an open interviewing technique, as described by Sällfors and Hallberg (2009), to explore the participants' subjectively experienced lifeworld. In order to collect as much open data as possible and avoid early saturation, we followed Hallberg's (2006) recommendation on late theoretical sampling and did not start theoretical coding until all interviewes had been performed 1 year after surgery.

The aim of this study was to investigate in-depth the process of change from the inside perspective of participants who underwent bariatric surgery. The design of this study is unique due to the combination of in-depth interviews, the inside perspective, and the prospective data collection. The use of Grounded Theory to analyse the data permitted a fundamental understanding of the issue of deburdening and control in the process of change from being morbidly obese, through bariatric surgery to becoming a healthier person who weighed much less. Our main finding was the core category: wishing for deburdening through a sustainable control over eating and weight, built on the three conceptual categories: Hoping for deburdening and control through surgery, Starting to feel deburdened and practising control through physical restriction, and Feeling deburdened and trying to maintain control by own willpower. Before surgery the participants experienced hopelessness and lack of control concerning their relationship to food and weight, which affected their family and social life as well as their mental and physical health. They were very burdened by obesity and they mainly viewed themselves negatively and believed that others despised them. Overall, they felt unable to control or change this vicious life circle. Surgery provided control over unhealthy eating habits, resulting in weight loss and leading to a very positive spin-off effect in many other areas of life. Feelings of empowerment and new found energy gave the participants the strength to improve their life situation within the family and society. For the first time in many years, the informants experienced being in charge of their total life situation instead of subjected to the restrictions of an obese body. Two years after surgery, when this “new” life had become routine, the participants still felt deburdened, but also strived to maintain control and improve the balance in terms of food intake, self-esteem, social life, as well as mental and physical well-being. The bodily signal system created by surgery was no longer the single key factor in maintaining weight loss. The participants described how their own willpower was necessary to sustain their changed behaviour towards food in order to maintain what they had achieved. A small group of participants was unable to maintain control over eating habits and started to gain weight. This led to fear of and anxiety about further weight gain and its consequences as well as serving as a reminder of how bad life had been before surgery. The process of change, from being morbidly obese to having a balanced life including a balanced nutritional intake and reasonable weight involved a strive at all levels to build a firm foundation for sustainable control over eating and weight, aimed at ensuring that life never collapses again.

This perspective concerned the participant's view of obesity as a disease and its consequences for his/her daily life. Previous studies, however, often present a perspective on symptoms of the disease based on patophysiology (Buchwald et al., 2004; Sjostrom et al., 2004). According to Toombs (1992), the outside and the inside perspective can also be termed the professional and the personal understanding of disease. These perspectives differ from each other in four respects:

The focus on the current situation

Attitude towards the disease

Relevance (i.e., what is important)

Perception of time

Both outside and inside perspectives are important and valid; there is no contradiction between them, but it is essential to be aware of the different perspectives and above all one's own personal attitude (Toombs, 1992). Staff members expect the patient to adhere to restrictions as well as advice regarding nutritional intake and recommended lifestyle changes. The participants, on the other hand, view the disease in terms of the consequences for their daily lives and interpret its meaning in a different way. One example is that the informants viewed dumping as an important control mechanism that prevented a relapse into food abuse. This was a completely new finding, in total contrast to earlier studies. None of our 16 participants reported dumping as something negative. Instead, they considered this symptom helpful for keeping up their new healthier lifestyle, and several reported how they wished for it to come back when it eased over time. However, from an outside and professional perspective based on patophysiology, dumping is viewed as an adverse side-effect after surgery.

In everyday clinical encounters we as health care professionals converse with and educate the bariatric patient mostly from an outside perspective, with little knowledge of adult patients' perspective on their recovery from bariatric surgery and transformed everyday life. We can capture the lived experiences of bariatric patients by illuminating their inside perspective by means of interviews. We can also learn from this perspective in order to improve nursing interventions, educational skills, and optimise encounters to be even more person centred and confirmatory. Supporting the strive for control as well as evaluating self-efficacy and overall strategies for mastering the situation of no longer being obese seems vital in the light of this study.

Within the literature we found similar results to our study. From an outside perspective, being unable to control one's eating behaviour has been discussed by White, Kalarchian, Masheb, Marcus, and Grilo (2009). Their questionnaire study revealed that before surgery, 61% of the participants reported uncontrolled feelings towards food intake and after 2 years this figure was reduced to 39%. Furthermore, they described how weight loss and psychosocial outcome were correlated with such feelings after surgery. However, these factors were not predictors of a negative outcome if only reported before the procedure. A similar conclusion can be drawn from our study, where the majority of participants expressed these feelings before surgery and a smaller group experienced them afterwards. From the inside perspective, our participants described how they had to struggle over time with their relationship to food by thinking more and more of what, why, and how they ate. The “bodily” restriction decreased for all participants but to various degrees. Some still had a strong bodily restriction after 2 years, while for others this was no major concern since new routines such as healthier food choices, set mealtimes, and less craving for sweets and junk food helped them to maintain their weight loss. Many of our participants were surprised and worried when the physical control started to fade. This could be viewed as a result of lack of information and preparation from, for example, the bariatric nurse. However, there is insufficient knowledge among clinicians about this reaction such a long time after surgery. The follow-up programme only lasts for 1 year and then the patients are supposed to manage on their own or seek help outside the hospital. On the basis of our results, we argue that these patients should be admitted to an out-patient support group and be enrolled in a long-term follow-up programme lasting at least 2 years. This is important since a small group was unable to keep to the restricted food intake and had started to gain weight 2 years after surgery. These participants blamed themselves and their character for being unable to control the situation. By providing access to support groups and sharing with other persons in the same situation, health care providers can help the bariatric patient to understand that several aspects are involved in the process of losing weight after surgery. Due to gastric hormones, all individuals have different preconditions when it comes to the feeling of restriction and/or dumping as well as hunger and satiation. This outside perspective might help these patients to change their negative opinion about themselves and not give up the struggle to maintain control.

The literature review by van Hout, Verschure, and van Heck (2005) involving quantitative research described how feelings of higher self-esteem can be a psychosocial predictor of success following bariatric surgery. Our result revealed how higher self-esteem was experienced by all participants after surgery, particularly during the first year. We draw the conclusion that the participants who were able to keep this higher self-esteem 2 years after surgery were able to maintain control over their weight as well as find a meaningful occupation. When this improved feeling lasted over time, many described how they took care of problems that occurred in the family, at work, uncontrolled food intake, and so on and did not merely accept a bad situation, as they had done many times before surgery. This aspect of being an active member of the family and society again has also been described by Magdaleno, Chaim, Pareja, and Turato (2009) who interviewed participants between 3 months and 3 years after bariatric surgery and analysed data using content analysis. The informants described how the experience of social reinsertion and acceptance was the most important benefit of surgery. They argued that it is of the utmost importance for the health care team to be aware of the absence of these important predictors, since they are directly influenced by self-esteem, which in turn is a strong positive predictive factor.

In spite of substantial weight loss, some informants still felt obese 1 year after surgery, leading to a more negative self-image. From an outside perspective, only focusing on the kilos lost, these patients might be viewed as successful, but from the inside perspective they had failed. Here, we as health care providers need to be sensitive so that we can strengthen their self-image and help them to continue their strive for further weight loss. Participants who still were unemployed 2 years after surgery described how they once again felt dejected, how they had started to eat for consolation, and how this despondent feeling also negatively affected their role in the family and society. This new knowledge provides us with information that the inside perspective can also make patients regress into unhealthy eating patterns. We cannot solve their unemployment problem, but we can support them to strive for sustainable eating control.

The participants in our study reported a mainly negative view of their relationship to health care before surgery, due to feelings of discrimination and ill-treatment caused by their bodily size. This has previously been described in two reviews (Brown, 2006; Reto, 2003). A new perspective is that patients felt frustrated when meeting health care providers with a great lack of knowledge about how morbid obesity should be treated. This led to a situation where some participants almost gave up, often avoiding new health care contacts, even those not concerning their obesity. This inside perspective highlights the important fact that all health care providers must be more sensitive to “new” treatments, and if not, many people will be exposed to unnecessary physical and mental suffering in our society. We also believe and agree with Fagerstrom (1998) that in order to care for obese patients we need to discuss bias among staff members, who have an obligation to understand, accept and adopt a professional attitude towards these patients. If we fail to establish a professional and holistic attitude towards the patients from the beginning, it will be difficult to create a relationship in which the patient feels safe to share his/her experiences and concerns.

Another health issue often reported 1 years after surgery was problems with surplus skin. Biorserud, Olbers, and Fagevik Olsen (2009) reported that 84% (94 out of 112) of the participants in their questionnaire study experienced problems with surplus skin after surgery, e.g., fungal infections, itching, physical unpleasantness, as well as problems performing physical activities. They found no correlation between the degree of experienced problems and age, weight loss, or activity and concluded that while surgery reduces medical risks some psychosocial problems may remain. Our participants described two problems in this area. First, the surplus skin itself, resulting in medical problems and perceived illness as reported by Biorserud et al., (2009). It also made them avoid situations similar to those they previously avoided due to their obesity, e.g., going for a swim or undressing in the presence of their partner. Having a body that looked much older than it was also affected their self-esteem. Secondly, they once again needed a health care intervention that is difficult to obtain, namely, plastic surgery. We know that due to lack of resources, this is a problem at many care centres that perform bariatric procedures today. Another issue concerning surplus skin and the current lack of resources is whether all bariatric patients should be offered cosmetic surgery, even if they do not have any medical problems. It is important that both before and after bariatric surgery, patients receive information and facts about surplus skin, for example, that it might become a problem, what kind of criteria the hospital uses for performing plastic surgery, and that the waiting time could be long.

Finally, our interpretation of the findings is that a key factor in wishing for deburdening through a sustainable control over eating and weight and for the bariatric patient lies in Bandura's (1977) socio-cognitive concept, self-efficacy. The participants need to believe in their own ability to achieve certain goals pertaining to the bariatric surgical treatment and not only rely on the surgery as such. Within the framework of a professional educational conversation, health care providers need to discuss the importance of realistic expectations from the procedure such as weight loss, possible weight regain, and why the latter may happen. This conversation is necessary in order to make the patients aware of their own role in a successful outcome. Reflecting on our findings, we believe that it can be difficult to convince patients about their self-efficacy before surgery but we must nevertheless attempt to do so. When higher self-esteem and empowerment emerge after surgery, we as health care providers can boost self-efficacy and support the patients' potential to achieve their own goals.

In summary, the process of change after bariatric surgery involves a fundamental striving to create a foundation for sustainable control over eating and weight. From both an inside and an outside perspective, the long-term goal after bariatric surgery is remarkably similar (i.e., sustainable control). From the professional perspective, this is achieved by a physical restraining system imposed by surgery. From the perspective of the bariatric patients, the goal is achieved by means of self-efficacy, the mental strength to maintain willpower and control over their eating behaviour. Factors supporting this strive are regained control over eating habits, substantial weight loss, and improved physical, mental, and social well-being. A cause of concern was that between 1 and 2 years after surgery, the physical control mechanism over the eating habits generally started to fade more or less for all informants. This led to fear of once again losing the grip on their eating behaviour and reverting to their poor pre-surgical condition as totally burdened by obesity. At this stage of the process, supportive and educational interventions seem essential in order to put those at risk of weight gain back on the right track. In order to achieve a satisfactory long-term outcome, today's fairly short follow-up programmes should be extended to at least 2 years after surgery and involve long-term and mandatory participation in, for example, a support group led by a bariatric nurse.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors report no conflict of interest, and they alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biorserud C., Olbers T., Fagevik Olsen M. Patients' experience of surplus skin after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obesity Surgery. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9849-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood H. S. Obesity: A rapidly expanding challenge. Nursing Management. 2004;35(5):27–35. doi: 10.1097/00006247-200405000-00009. quiz 35–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocchieri L. E., Meana M., Fisher B. L. Perceived psychosocial outcomes of gastric bypass surgery: A qualitative study. Obesity Surgery. 2002;12(6):781–788. doi: 10.1381/096089202320995556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown I. Nurses' attitudes towards adult patients who are obese: Literature review. Journal of Advance Nursing. 2006;53(2):221–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald H., Avidor Y., Braunwald E., Jensen M. D., Pories W., Fahrbach K., et al. Bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(14):1724–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Earvolino-Ramirez M. Living with bariatric surgery. Totally different but still envolving. Bariatric Nursing and Surgical Patient Care. 2008;3(1):17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom L. The patient's perceived caring needs as a message of suffering. Journal of Advance Nursing. 1998;28(5):978–987. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glinski J., Wetzler S., Goodman E. The psychology of gastric bypass surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2001;11(5):581–588. doi: 10.1381/09608920160557057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallberg L. The “core category” of grounded theory: Making constant comparisons. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being. 2006;1(3):141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu L. K., Benotti P. N., Dwyer J., Roberts S. B., Saltzman E., Shikora S., et al. Nonsurgical factors that influence the outcome of bariatric surgery: A review. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1998;60(3):338–346. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson J., Taft C., Ryden A., Sjostrom L., Sullivan M. Ten-year trends in health-related quality of life after surgical and conventional treatment for severe obesity: The SOS intervention study. International Journal of Obesity. 2007;31:1248–1261. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le Roux C. W., Welbourn R., Werling M., Osborne A., Kokkinos A., Laurenius A., et al. Gut hormones as mediators of appetite and weight loss after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Annals of Surgery. 2007;246(5):780–785. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180caa3e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdaleno R., Jr., Chaim E. A., Pareja J. C., Turato E. R. The psychology of bariatric patient: What replaces obesity? A qualitative research with Brazilian women. Obesity Surgery. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9824-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näslund I., Boman L., Näslund E., Granström L., Hedenbro J., Krook H., et al. NIOK 2.0: Nationella Indikationer för Obesitas Kirurgi. 2009. Retrieved December 1, 2010, from http://www.sfoak.se/wp-content/niok_2009.pdf.

- Ogden J., Clementi C., Aylwin S. The impact of obesity surgery and the paradox of control: A qualitative study. Psychology & Health. 2006;21(2):273–293. doi: 10.1080/14768320500129064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden J., Clementi C., Aylwin S., Patel A. Exploring the impact of obesity surgery on patients' health status: A quantitative and qualitative study. Obesity Surgery. 2005;15(2):266–272. doi: 10.1381/0960892053268291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reto C. S. Psychological aspects of delivering nursing care to the bariatric patient. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly. 2003;26(2):139–149. doi: 10.1097/00002727-200304000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sällfors C., Hallberg L. Fitting into the prevailing teenage culture: A grounded theory on female adolescents with chronic arthritis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being. 2009;4(4):106–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sjostrom L., Lindroos A. K., Peltonen M., Torgerson J., Bouchard C., Carlsson B., et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351(26):2683–2693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sovik T. T., Taha O., Aasheim E. T., Engstrom M., Kristinsson J., Bjorkman S., et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic gastric bypass versus laparoscopic duodenal switch for superobesity. The British Journal of Surgery. 2009;97(2):160–166. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toombs S. K. The meaning of illness: A phenomenological account of the different perspectives of physician and patient. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hout G. C., Leibbrandt A. J., Jakimowicz J. J., Smulders J. F., Schoon E. J., Van Spreeuwel J. P., et al. Bariatric surgery and bariatric psychology: General overview and the Dutch approach. Obesity Surgery. 2003;13(6):926–931. doi: 10.1381/096089203322618795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hout G. C., Verschure S. K., van Heck G. L. Psychosocial predictors of success following bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2005;15(4):552–560. doi: 10.1381/0960892053723484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White M. A., Kalarchian M. A., Masheb R. M., Marcus M. D., Grilo C. M. Loss of control over eating predicts outcomes in bariatric surgery patients: A prospective, 24-month follow-up study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;71(2):175–184. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04328blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO homepage. 2010 Retrieved December 1, 2010, from http://www.who.int/topics/obesity/en/

- Wysoker M. The lived experienced of choosing bariatric surgery to lose weight. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2005;11(1):26–34. [Google Scholar]