Abstract

CXCR4, a chemokine receptor, plays an important role in breast cancer growth, invasion, and metastasis. The transcriptional targets of CXCR4 signaling are not known. Microarray analysis of CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low subpopulations of the MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line, which has a constitutively active CXCR4 signaling network, revealed differential expression of ∼ 200 genes in the CXCR4-enriched subpopulation. ITF2, upregulated in CXCR4-enriched cells, was investigated further. Expression array datasets of primary breast tumors revealed higher ITF2 expression in estrogen receptor negative tumors, which correlated with reduced progression free and overall survival and suggested its relevance in breast cancer progression. CXCL12, a CXCR4 ligand, increased ITF2 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells. ITF2 is a basic helixloop-helix transcription factor that controls the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and the function of the ID family (inhibitor-of-differentiation) of transcription factors, such as ID2. ID2 promotes differentiation of breast epithelial cells and its reduced expression in breast cancer is associated with an unfavorable prognosis. Both CXCR4 and ITF2 repressed ID2 expression. In xenograft studies, CXCR4-enriched cells formed large tumors and exhibited significantly elevated lung metastasis. Short interfering RNA against ITF2 reduced invasion of the CXCR4-enriched MDA-MB-231 subpopulation, whereas ITF2 overexpression restored the invasive capacity of MDA-MB-231 cells expressing CXCR4shRNA. Furthermore, overexpression of ITF2 in these cells enhanced tumor growth. We propose that ITF2 is one of the CXCR4 targets, which is involved in CXCR4-dependent tumor growth and invasion of breast cancer cells.

Key words: CXCR4, breast cancer, ID2, ITF2B, invasion

Introduction

Metastasis is a non-random and organ-selective process. A number of proteins have been implicated in metastasis of breast cancer including chemokines and their receptors.1,2 Chemokines bind to their cognate G-protein coupled receptors to elicit a cellular response such as chemotaxis.3 Tumor cells and stroma secrete chemokines, which facilitate tumor growth through increased endothelial cell recruitment, subversion of immune surveillance and leukocyte trafficking.3,4 Additionally, chemokines facilitate organ-specific homing and metastasis.3

The chemokine CXCL12/SDF1α (stromal cell-derived factor-1α) and its receptor CXCR4 have received considerable attention due to overexpression of CXCR4 in at least 21 different types of cancers.3 The role of CXCR4 in organ specific metastasis was first described in breast cancer.5 Subsequent studies identified CXCR4 as a part of bone metastasis signature and with poor prognosis.6,7 CXCR4-mediated signaling is linked to HER2-mediated breast cancer progression and brain metastasis.8,9 We reported clonal selection of CXCR4-enriched cancer cells in the primary tumor and lung metastasis in a MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell-derived xenograft model.10 In several experimental models, CXCR4 inhibition resulted in reduced primary tumor growth and/or metastasis.11,12

CXCL12 secreted by the tumor cells or by the stroma activate CXCR4 in cancer cells.4,13 CXCL12-independent activation of CXCR4 through crosstalk with growth factor receptors has been reported.14 Recent studies have identified two non-cognate ligands for CXCR4: Trefoil factor 2 (TFF2) and macrophage migration inhibitory factor.15,16 However, signaling molecules that mediate the CXCR4 action within breast cancer cells are unknown. Using MDA-MB-231 cells as a model system, we have identified class I basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family transcription factors being involved in CXCR4 action.

Class I bHLH proteins are involved in cell growth and differentiation. These proteins form homodimers and heterodimers with other classes of bHLH proteins and recognize a consensus DNA sequence termed E-box.17 A related class of proteins, inhibitor-of-differentiation (IDs 1–4), lacks the DNA binding domain but dimerizes with bHLH proteins including ITF2 (immunoglobulin transcription factor, also called E2-2, SEF-2 and TCF4) and modulates the activity of bHLH proteins.17,18 ITF2, which is the focus of this study, is expressed as two isoforms, A and B, and displays transforming ability.18 ITF2, ID1 and ID2 comprise a network of transcription factors that govern proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis of mammary epithelial cells.19 We observed CXCR4-mediated upregulation of ITF2B and consequently reduced expression of ID2. We propose that CXCR4 mediated signaling pathways control the levels of ID2 homodimers and ID2:ITF2 heterodimers in cancer cells and this shift in the dynamics of these complexes impacts the expression of genes involved in metastatic progression.

Results

CXCR4-enriched subpopulation express unique set of genes.

We and others have observed that only a subset of cells in the breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 express CXCR4; these CXCR4-positive cells isolated through clonal selection show distinct biological properties.7,10 Similar differences in the biological properties of CXCR4-positive and CXCR4-negative subpopulation of cancer cells have been reported in pancreatic cancer.20 These observations prompted us to determine the gene expression pattern in CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low subpopulation to identify genes that are co-expressed with CXCR4 in breast cancer cells. We used tumor derived MDA-MB-231 cells (TMD-231) in which ∼30% of cells are CXCR4-positive.10 These cells have constitutively active CXCR4 due to crosstalk with growth factor receptors and display invasive properties without CXCL12 treatment in matrigel assays.14,21 Additionally, these cells express ∼200 fold higher levels of TFF2, a non-canonical ligand for CXCR4,16 compared to other breast cancer cell lines (Fig. 1A). Neutralizing antibodies against CXCR4 inhibit invasion of these cells, thus confirming constitutive activity of this receptor in these cells.21

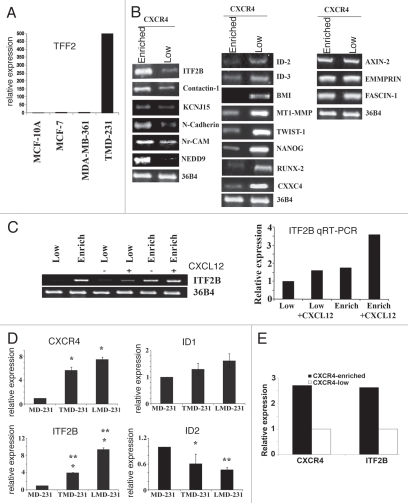

Figure 1.

CXCR4-dependent changes in gene expression in breast cancer cells. (A) TMD-231 cells express higher levels of TFF2, a CXCR4 ligand, compared to other breast cancer cell lines. TFF2 transcript levels were measured by qRT-PCR. (B) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of differentially expressed genes in CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low subpopulation of TMD-231 cells. Genes expressed at higher (left), lower (middle) or similar levels (right) in CXCR4-enriched compared to CXCR4-low cells are shown. (C) The effect of CXCL12 on ITF2B expression in CXCR4-low and CXCR4-enriched cells. Cells were treated with CXCL12 (100 ng/ml for four hours) and ITF2B expression was measured by RT-PCR and qRT-PCR. 36B4 was used as a control for RT-PCR. (D) ITF2B expression is elevated in TMD-231 and LMD-231 cells compared to parental MDA-MB-231 (MD-231) cells. Note that ID2 expression is lower in TMD-231 and LMD-231 compared to parental MDA-MB-231 cells. For CXCR4, *p ≤ 0.006 MD-231 versus TMD-231 or LMD-231; for ITF2B, *p ≤ 0.0009 MD-231 versus TMD-231 or LMD-231; for ID2, *p = 0.02 MD-231 versus TMD-231, **p = 0.004 MD-231 versus LMD-231. Difference in expression of ITF2B was significantly different between TMD-231 and LMD-231 (**p = 0.002). (E) CXCR4 and ITF2B show similar pattern of expression in CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low cells. CXCR4 and ITF2B expression was measured by qRT-PCR.

Among genes that showed more than 2-fold difference in expression with a p value of <0.05, 114 genes showed elevated expression (Table 1) and 97 genes showed reduced expression (Table S1) in cells expressing higher levels of CXCR4 (labeled CXCR4-enriched hereafter) compared to cells expressing lower level of CXCR4 (CXCR4-low). Difference in the expression levels of CXCR4 between CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low cells was 6.8-fold as per microarray analysis (Table 1); we have previously confirmed elevated expression of CXCR4 in CXCR4-enriched cells by RNAse protection assay.22 Consistent with the constitutive activity of CXCR4 in these cells, treatment of CXCR4-enriched cells with CXCL12 (100 ng/ml for 4 hours) resulted in elevated expression of additional 13 genes and downregulation of 11 genes (Table S2).

Table 1.

Genes upregulated in CXCR4-enriched cells compared to CXCR4-low cells

| Gene symbol | Genbank | Fold change | t-test | Description |

| THBS1 | NM_003246 | 3.16 | 9.08E-07 | thrombospondin1 |

| NEDD9 | NM_182966 | 3.43 | 1.54E-05 | neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally downregulated 9 |

| NNMT | NM_006169 | 3.62 | 3.75E-09 | nicotinamide N-methyltransferase |

| MATN2 | NM_030583 | 2.76 | 5.36E-06 | matrilin 2 |

| NRIP1 | NM_003489 | 3.61 | 1.04E-05 | nuclear receptor interacting protein 1 |

| THBS2 | NM_003247 | 6.9 | 1.39E-05 | thrombospondin 2 |

| DAPK1 | NM_004938 | 3.07 | 2.09E-05 | death-associated protein kinase 1 |

| ALDH1A3 | NM_000693 | 2.79 | 2.34E-04 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member A3 |

| SOCS2 | NM_003877 | 2.57 | 4.76E-05 | suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 |

| SGNE1 | NM_003020 | 4.67 | 6.39E-07 | secretory granule, neuroendocrine protein 1 (7B2 protein) |

| SLC4A4 | NM_003759 | 2.58 | 3.11E-06 | solute carrier family 4, sodium bicarbonate cotransporter, member 4 |

| ALOX5AP | NM_001629 | 3.54 | 4.98E-06 | arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein |

| RGS4 | NM_005613 | 5.01 | 1.75E-06 | regulator of G-protein signaling 4 |

| ARK5 | 2.8 | 6.77E-06 | KIAA 0537 gene product | |

| ITGB3 | NM_000212 | 3.15 | 1.66E-05 | integrin, beta3 (platelet glycoprotein IIIa, antigen CD61) |

| NAP1L3 | NM_004538 | 3.56 | 2.94E-07 | nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 3 |

| INHBA | NM_002192 | 7.74 | 1.83E-09 | inhibin, beta A (activin A, activin ABalpha polypeptide) |

| IL1B | NM_000576 | 3.98 | 2.82E-07 | interleukin 1beta |

| COCH | NM_004086 | 2.5 | 3.21E-04 | coagulation factor C homolog, cochlin (Limulus polyhemus) |

| TAGLN | NM_003186 | 15.3 | 6.39E-06 | transgelin |

| KISS1 | NM_002256 | 7.74 | 4.70E-06 | KiSS-1 metastasis-suppressor |

| WT1 | NM_024426 | 7.6 | 6.23E-06 | Wilms tumor 1 |

| RGS7 | NM_002924 | 4.06 | 3.88E-07 | regulator of G-protein signaling 7 |

| PCTK2 | NM_002595 | 2.59 | 5.04E-06 | PICTAIRE protein kinase 2 |

| CYP24A1 | NM_000782 | 3.29 | 2.26E-04 | cytochrome P450, family 24, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 |

| IL24 | NM_181339 | 3.16 | 2.77E-05 | interleukin 24 |

| EMR1 | NM_001974 | 6.85 | 1.02E-07 | egf-like module containing, mucin-like, hormone receptor-like 1 |

| RBPMS | NM_006867 | 3.77 | 7.75E-06 | RNA binding protein with multiple splicing |

| FGF5 | NM_033143 | 2.68 | 2.87E-06 | fibroblast growth factor 5 |

| LCP1 | NM_002298 | 4.61 | 4.20E-07 | lymphocyte cytosolic protein 1 (L-plastin) |

| CXCR4 | NM_003467 | 6.81 | 1.53E-07 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 |

| PSCDBP | NM_004288 | 5.03 | 2.75E-04 | pleckstrin homology, Sec7 and coiled-coil domains, binding protein |

| TRIM9 | NM_052978 | 3.77 | 1.33E-04 | tripartite motif-containing 9 |

| IL1A | NM_000575 | 4.33 | 2.75E-05 | interleukin 1alpha |

| KCNJ15 | NM_170737 | 9.99 | 1.08E-05 | potassium inwardly-rectifying channel, subfamily J, member15 |

| PTPRR | NM_130846 | 2.88 | 7.10E-05 | protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, R |

| POSTN | NM_006475 | 8.24 | 7.75E-04 | osteoblast specific factor 2 (fasciclin I-like) |

| AF1Q | NM_006818 | 2.95 | 8.34E-07 | ALL1-fused gene from chromosome 1q |

| TCF4/ITF-2 | NM_003199 | 6.31 | 8.91E-05 | transcription factor 4 |

| FN1 | NM_054034 | 2.54 | 1.27E-08 | fibronectin 1 |

| QKI | 3.44 | 4.61E-07 | quaking homolog, KH domain RNA binding (mouse) | |

| 3.94 | 1.74E-05 | Homo sapiens mRNA; cDNA DKFZp564B222 | ||

| PDE1C | NM_005020 | 2.53 | 1.09E-04 | phosphodiesterase 1C, calmodulin-dependent 70 kDa |

| PDGFD | NM_033135 | 3.68 | 2.30E-06 | spinal cord-derived growth factor-B |

| AK5 | NM_174858 | 3.16 | 2.23E-05 | adenylate kinase 5 |

| CENTA2 | NM_018404 | 3.15 | 2.10E-05 | centaurin, alpha2 |

| AHI1 | NM_017651 | 3.05 | 1.23E-05 | Abelson helper integration site |

| ADAMTS1 | NM_006988 | 6.09 | 1.94E-09 | a disintegrin-like and metalloprotease (reprolysin type) with thrombospondin type 1 motif 1 |

| FLJ11036 | NM_018306 | 10.3 | 3.50E-04 | hypothetical protein FLJ11036 |

| 8.6 | 6.34E-08 | Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ11041 fis, clone PLACE 1004405 | ||

| CNTN1 | NM_175038 | 10.2 | 6.57E-04 | contactin 1 |

| FLJ22761 | NM_025130 | 3.5 | 1.09E-06 | hypothetical protein FLJ22761 |

| 2.74 | 2.50E-06 | Homo sapiens LOC374963 (LOC374963), mRNA | ||

| DKFZp686A17109 | NM_198465 | 7.45 | 6.78E-08 | hypothetical protein DKFZp686A17109 |

| HAK | NM_052947 | 7.09 | 1.22E-07 | heart alpha-kinase |

| C6orf105 | NM_032744 | 2.62 | 2.86E-06 | chromosome 6 open reading frame 105 |

| 3.05 | 3.34E-05 | Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ41433 fis, clone BRHIP2007307 | ||

| F2RL2 | NM_004101 | 6.19 | 9.10E-06 | coagulation factor II (thrombin) receptor-like 2 |

| HAS2 | NM_005328 | 2.56 | 1.97E-06 | hyaluronan synthase 2 |

| 4.91 | 2.89E-04 | Homo sapiens transcribed sequence with weak similarity to protein pir:I49130 (M. musculus) I49130 revese transcriptase—mouse | ||

| NOG | NM_005450 | 2.71 | 1.41E-06 | noggin |

| ODZ2 | 6.25 | 1.57E-07 | odd Oz/ten-m homolog 2 | |

| FLJ23657 | NM_178497 | 6.07 | 4.58E-05 | hypothetical protein FLJ23657 |

| BMPER | NM_133468 | 4.56 | 9.01E-05 | BMP-binding endothelial regulator precursor protein |

| MGC40222 | NM_152738 | 3.17 | 9.02E-06 | hypothetical protein MGC40222 |

| C20orf75 | NM_152611 | 3.14 | 1.94E-04 | chromosome 20 open reading frame 75 |

| MGC23985 | 2.68 | 2.15E-06 | Homo sapiens clone DNA56859 AVLV472 (UNQ472) mRNA, complete cds | |

| ANXA8 | NM_001630 | 3.53 | 1.06E-06 | annexin A8 |

| CDH2 | NM_001792 | 5.06 | 1.97E-04 | cadherin 2, type 1, N-cadherin (neuronal) |

| NRCAM | NM_005010 | 3.56 | 1.05E-04 | neuronal cell adhesion molecule |

| HSD17B2 | NM_002153 | 3.54 | 1.20E-04 | hydroxysteroid (17-beta) dehydrogenase 2 |

| RARB | NM_016152 | 3.22 | 1.46E-05 | retinoic acid receptor, beta |

| BAI3 | NM_001704 | 5.43 | 1.53E-04 | brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor 3 |

| NCAM2 | NM_004540 | 4.17 | 3.91E-03 | neural cell adhesion molecule 2 |

| SLC3A1 | NM_000341 | 3.03 | 3.03E-04 | solute carrier family 3 (cystine, dibasic and neutral amino acid transporters) |

| MATN3 | NM_002381 | 3.91 | 1.09E-03 | matrilin 3 |

| MAGEC1 | NM_005462 | 3.02 | 3.50E-04 | melanoma antigen, family C, 1 |

| GCKR | NM_001486 | 3.99 | 1.77E-04 | glucokinase (hexokinase 4) regulatory protein |

| HCK | NM_002110 | 3.54 | 5.34E-03 | hemopoietic cell kinase |

| ESM1 | NM_007036 | 3.45 | 2.36E-06 | endothelial cell-specific molecule 1 |

| ENPP2 | NM_006209 | 3.22 | 4.63E-03 | ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 2 (autotaxin) |

| OLR1 | NM_002543 | 4.73 | 9.13E-06 | oxidised low density lipoprotein (lectin-like) receptor 1 |

| CSPG2 | NM_004385 | 3.39 | 1.99E-03 | chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 2 (versican) |

| KIAA1199 | NM_018689 | 4.74 | 3.09E-03 | KIAA1199 protein |

| HNOEL-iso | NM_020190 | 3.81 | 1.75E-04 | HNOEL-iso protein |

| SNCAIP | NM_005460 | 3.05 | 5.01E-04 | synuclein, alpha interacting protein (synphilin) |

| ADAMTS5 | NM_007038 | 3.84 | 3.87E-03 | a disintegrin-like and metalloprotease (reprolysin type) with thrombospondin type 1 motif 5 (aggrecanase-2) |

| LRRC2 | NM_024750 | 3.84 | 8.60E-05 | leucine rich repeat containing 2 |

| TPTE | NM_199261 | 3.06 | 3.54E-03 | transmembrane phosphatase with tensin homology |

| COLEC12 | NM_130386 | 3.99 | 2.13E-04 | collectin sub-family member 12 |

| HTR1F | NM_000866 | 3.07 | 1.75E-02 | 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 1F |

| TMLHE | NM_018196 | 4.65 | 3.83E-04 | trimethyllysine hydroxylllase, epsilon |

| CHST9 | NM_031422 | 10.1 | 6.02E-05 | carbohydrate (N-acetylgalactosamine 4-0) sulfotransferase 9 |

| PGM5 | NM_021965 | 3.13 | 1.61E-05 | phosphoglucomutase 5 |

| MOBKL2B | NM_024761 | 3.21 | 2.27E-04 | MOB3B protein |

| LAMA1 | NM_005559 | 4.37 | 1.72E-03 | laminin, alpha1 |

| MUC15 | NM_145650 | 4.59 | 8.63E-04 | mucin 15 |

| FLJ38507 | NM_016206 | 3.59 | 1.87E-04 | colon carcinoma related protein |

| JPH2 | NM_175913 | 3.57 | 1.81E-03 | junctophilin 2 |

| 3.43 | 4.40E-05 | Homo sapien similar to speckle-type POZ protein (LOC339744), mRNA | ||

| KIAA1462 | 5.42 | 6.70E-05 | KIAA 1462 protein | |

| 6.7 | 1.07E-04 | Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ11825 fis, clone HE MBA1006494 | ||

| 3.19 | 2.35E-02 | Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ11655 fis, clone HE MBA1004554 | ||

| UNQ3033 | NM_198481 | 5.06 | 3.17E-06 | LAIR hlog |

| KCTD4 | NM_198404 | 3.92 | 4.43E-04 | potassium channel tetramerisation domain containing 4 |

| 3 | 1.05E-04 | Human full-length cDNA 5-PRIME end of clone CS0DK007YB08 of HeLa cells of Homo sapiens (human) | ||

| 12.4 | 8.16E-07 | Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:5223469, partial cds | ||

| NEK11 | NM_145910 | 3.58 | 9.66E-03 | NIMA (never in mitosis gene a)—related kinase 11 |

| 5.96 | 2.57E-03 | Homo sapiens, clone IMAGE:5275263, mRNA | ||

| NY-BR-1.1 | 3.94 | 9.77E-04 | breast cancer antigen NY-BR-1.1 | |

| FLJ39531 | 4.77 | 1.72E-04 | Homo sapiens mRNA; cDNA DKFZp686B03201 (from clone DKFZp686B03201) | |

| 6.93 | 8.64E-06 | Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ25867 fis, clone CBR02018 | ||

| 3.54 | 1.73E-03 | Homo sapiens, clone IMAGE:5556045, mRNA | ||

| IQGAP3 | NM_178229 | 3.28 | 4.28E-04 | IQ motif containing GTPase activating protein 3 |

Kang et al. had previously characterized single cell-derived clones from MDA-MB-231 cells with propensity to metastasize to bones.7 These bone metastatic cells overexpressed 11 genes (CXCR4, IL-11, FGF5, ADAMTS1, NAP1L3, CTGF, FST, PRG1, NCF2, DUSP1 and MMP1) at 4-fold or higher levels compared to low metastatic clones. Three of these genes (FGF5, ADAMTS1 and NAP1L3) are overexpressed in CXCR4-enriched subpopulation compared to CXCR4-low subpopulation (Table 1). NEDD9, which has recently been linked to breast epithelial cell migration and metastasis,23,24 is expressed at higher levels in CXCR4-enriched cells. CXCR4-enriched cells displayed elevated expression of several pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin 1alpha (IL-1α) and IL-1β, which may be responsible for CXCR4 expression in these cells.10

CXCR4-enriched cells showed elevated expression of Kiss1, a metastasis suppressor gene, as well as thrombospondin 1 and thrombospondin 2, genes described to have both pro-metastatic and anti-metastatic activity.1,25 SPARC, an extracellular matrix protein involved in tumor-stroma interaction and is generally associated with metastasis,26 was expressed at higher level in CXCR4-low cells (Table S1). This protein, however, has been shown to reduce metastasis of MDA-MB-231 cells.27 Overall, the expression of genes associated with invasion and metastasis is elevated in CXCR4-enriched cells.

We validated differential expression of several of the candidate genes by semiquantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 1B). Similar to results of microarray analysis, the expression of KCNJ15, N-Cadherin, Contactin-1, TCF-4/ITF2 and NEDD9 was elevated in CXCR4-enriched cells (Fig. 1B, left), whereas the expression of ID2, ID3 and CXXC4 was lower in CXCR4-enriched cells (Fig. 1B, middle). We also examined the expression pattern of TWIST and MT1-MMP, which are linked to breast cancer invasion and/or metastasis.28,29 Interestingly, both of these genes were expressed at higher level in CXCR4-low cells. AXIN-2, Emmprin and FASCIN-1 are expressed at similar level in both cell types (Fig. 1B, right).

Previous studies have shown elevated CXCR4 expression in undifferentiated normal breast epithelial cells compared to differentiated cells.30 Therefore, we examined the expression pattern of BMI-1 and Nanog, which are linked to stemness phenotype. Surprisingly, the expression levels of all three of these genes were higher in CXCR4-low cells compared to CXCR4-enriched cells. Taken together, our results highlight differences in expression pattern of genes associated with invasion and metastasis among CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low cells.

To identify signaling pathways that may be active in CXCR4-enriched cells compared to CXCR4-low cells, we performed Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Ingenuity systems, Inc., Redwood city, CA) using genes elevated or downregulated in CXCR4-enriched cells. With genes elevated in CXCR4-enriched cells, three pathways were identified: NFκB/AP-1/TGFβ, IL-1 signaling and Wnt/β-catenin signaling linked to ITF2 (Fig. S1–3). We performed studies to evaluate the link between ITF2 and CXCR4 because ITF2 forms a network with ID family proteins and relatively little is known about the role of this protein in breast cancer.17

ITF2 expression is CXCL12 inducible and is elevated in cancer cells derived from tumors and metastatic sites compared to parental cells.

ITF2, a class I bHLH transcription factor, is a transforming gene downstream of Wnt/β-catenin.18 ITF2 (NM_003199) is also named TCF4 in the literature and is distinct from TCF4 (NM_009333) of the nuclear β-catenin transcription complex. ITF2B is the predominant isoform in majority of breast cancer cell lines (data not shown). Its expression was four-fold higher in CXCR4 enriched cells compared to CXCR4-low cells in our microarray (Table 1). To determine whether CXCR4/CXCL12 directly regulates ITF2B expression, we treated CXCR4-low and CXCR4-enriched cells with CXCL12 and measured ITF2B expression by semiquantitative RT-PCR and quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 1C left and right parts, respectively). CXCL12 increased ITF2B expression suggesting that CXCR4/CXCL12 activated signaling pathway directly regulates ITF2B expression. CXCL12 also increased ITF2B in MDA-MB-361 cell line, albeit modestly, possibly due to lower CXCR4 levels in these cells compared to MDA-MB-231 cells (data not shown).

We had previously reported elevated expression of CXCR4 in MDA-MB-231 cells grown as a primary tumor in the mammary fat pad of nude mice and in cancer cells that have metastasized to lungs compared to cultured parental cells.10 Elevated ITF2 expression is expected in tumor-derived (TMD-231) or lung metastasis-derived (LMD-231) MDA-MB-231 cells compared to parental cells, if ITF2 expression is regulated by CXCR4. Indeed, ITF2 expression was low in parental cells but markedly elevated in TMD-231 and LMD-231 cells (Fig. 1D). ID1 expression was similar to that of CXCR4, whereas ID2 expression showed inverse correlation with CXCR4 (Fig. 1D), which is consistent with the differences in ID2 expression observed between CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low cells (Fig. 1B). We confirmed a direct link between CXCR4 and ITF2B expression in CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low cells by qRT-PCR. A threefold enrichment of CXCR4 correlated with a three-fold increase in ITF2B expression (Fig. 1E). Thus, ITF2 expression parallels with CXCR4 expression.

ITF2 expression correlates with poor prognosis in estrogen receptor negative breast cancer.

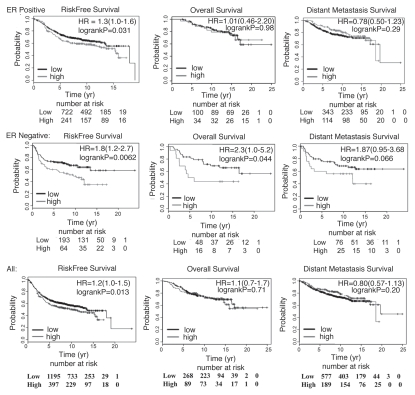

CXCR4 expression at protein level in primary breast cancer is associated with estrogen receptor alpha (ER) negativity and aggressive tumor growth.6 We used the recently reported online tool to analyze the expression levels of genes of interest in primary breast cancers and relate expression with survival.31 To avoid the influence of treatment on outcome, only truly prognostic datasets with no systemic therapy (GSE11121, GSE7390 and selected data from GSE3494, 2990 and 2034) were analyzed. Patients with expression levels at the upper quartile were grouped into high expression group and the remaining as low expression group. Survival analysis was done with the ER-positive, the ER-negative subgroups or all patients combined. In the ER-positive and all patients groups, risk free survival but not overall and metastasis free survival was significantly lower among patients with tumors expressing higher levels of ITF2 (Fig. 2 and for the ER-positive, p = 0.031; for all patients p = 0.013). In the ER-negative subgroup, risk free and overall survival was significantly lower among patients with tumors expressing higher levels of ITF2B (p = 0.0062 and 0.044 for risk free and overall survival, respectively). Metastasis free survival also showed a similar trend although differences did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.066). Overall, these results suggest a role for ITF2 expression in breast cancer progression, which may be dependent on breast cancer subtype. In the same dataset, higher CXCR4 expression correlated with reduced risk free (p < 0.00001) but not overall or metastasis free survival when data from all patients were considered (data not shown). CXCR4 expression lost prognostic utility when the analysis was restricted to the ER-positive or the ER-negative subgroups. Nonetheless, the above results showing a prognostic significance of ITF2 in primary breast cancer prompted us to perform additional studies of this molecule.

Figure 2.

ITF2B expression correlates with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses of patients with low and high ITF2 (upper quartile) expressing tumors are shown. Data from patients who had not received any systemic therapy were included. Analyses were as follows: patients with ER-positive tumors (top), ER-negative (middle) and all patients (bottom). Number of patients at risk in each subgroups at 0, 5, 10, 15 and 20 years post diagnosis along with hazard ratio (HR) and log rank p values are indicated.

ITF2 is downstream of CXCR4.

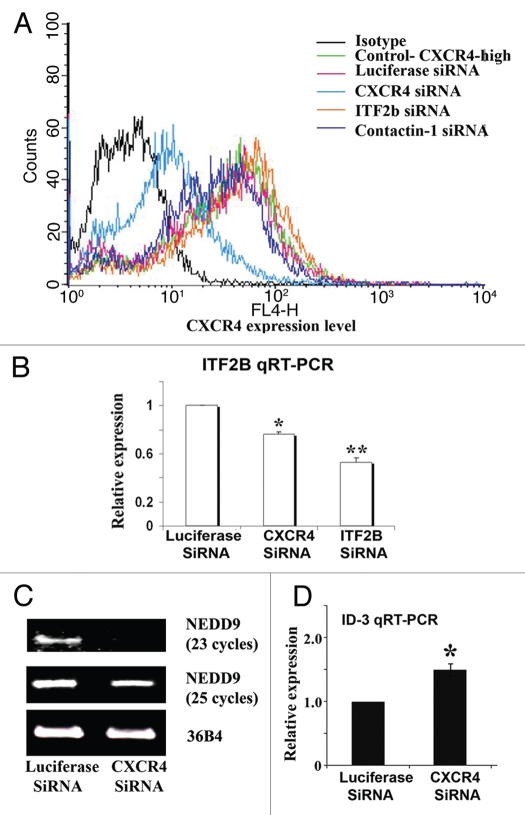

The modest effect of exogenous CXCL12 in increasing ITF2B expression in CXCR4-enriched cells suggested that the CXCR4 is already active in these cells. To further determine whether ITF2B is downstream of CXCR4, we reduced CXCR4 levels in CXCR4-enriched cells by siRNA. Cell surface CXCR4 protein levels were substantially lower in CXCR4 siRNA treated cells compared to control luciferase siRNA treated cells (Fig. 3A). The siRNA targeting ITF2 or contactin-1, another CXCR4-enriched cell overexpressed gene involved in Notch signaling,32 did not reduce CXCR4 levels (Fig. 3A). ITF2 levels were lower in CXCR4 siRNA and ITF2 siRNA treated cells (Fig. 3B). Although CXCR4 siRNA treated cells showed statistically significant reduction in ITF2B expression compared to control siRNA treated cells, 50% reduction in CXCR4 did not lead to similar reduction in ITF2B levels. This is not surprising since ITF2 expression is regulated by several transcription factors including β-catenin18 and these transcription factors may still contribute to ITF2B expression under conditions of lower CXCR4.

Figure 3.

ITF2B is a downstream target of CXCR4. (A) Flow cytometry of TMD-231 treated with control luciferase siRNA, CXCR4 siRNA, ITF2B siRNA or Contactin-1 siRNA for CXCR4 expression. (B) CXCR4 siRNA treated cells show reduced ITF2B expression. ITF2B expression was measured by qRT-PCR. *p = 0.003, luciferase siRNA versus CXCR4; **p = 0.002 luciferase siRNA versus ITF2B siRNA. (C) CXCR4 siRNA treated cells show reduced NEDD9 expression. RT-PCR was used to measure NEDD9 expression. (D) CXCR4 siRNA treated cells show elevated ID3. qRT-PCR was used to measure ID3. *p = 0.02 luciferase siRNA versus CXCR4 siRNA.

To determine whether positive correlation between NEDD9 and CXCR4 and negative correlation between ID3 and CXCR4 (Fig. 1 and Table S1) is linked to CXCR4 signaling or coincidental, we examined the expression levels of NEDD9 and ID3 in control luciferase and CXCR4 siRNA treated cells. NEDD9 expression was lower, whereas ID3 expression was higher in CXCR4 siRNA treated cells (Fig. 3C and D).

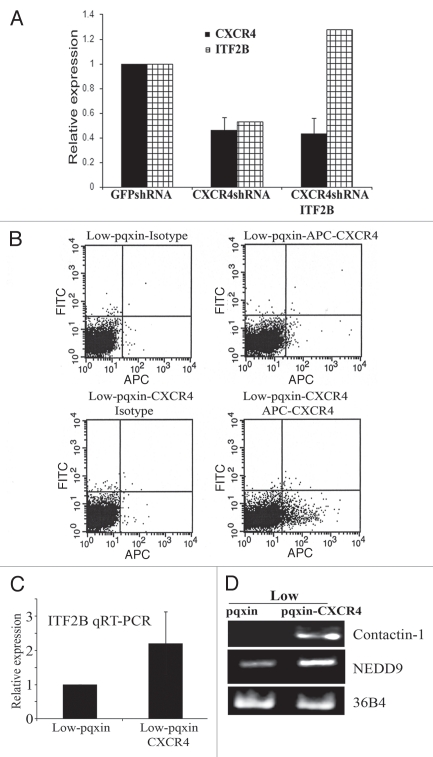

To further establish a direct link between CXCR4 and ITF2B, two additional series of experiments were performed. In the first series, we generated CXCR4-enriched cells stably expressing CXCR4 shRNA and the same cells overexpressing ITF2B (CXCR4shRNA-ITF2B) (Fig. 4A). GFPshRNA expressing cells were generated as controls. CXCR4shRNA cells expressed 60% lower CXCR4 transcripts compared to control GFPshRNA cells (Fig. 4A). As with siRNA treated cells, ITF2 expression was also reduced in CXCR4shRNA cells compared to GFPshRNA cells (Fig. 4A). In these stable cell lines, CXCR4 and ITF2B expression showed similar expression pattern. ITF2B overexpression in CXCR4shRNA cells had no effect on the CXCR4 status at mRNA level (Fig. 4A). Flow cytometry experiments confirmed lower levels of cell surface CXCR4 in CXCR4shRNA cells compared to GFPshRNA cells and the inability of ITF2B to rescue CXCR4 expression (data not shown). In the second series of experiments, we overexpressed CXCR4 in CXCR4-low cells by retrovirus mediated gene transfer (Fig. 4B). Despite selection of cells with a selectable marker, only ∼10% of cells expressed cell surface CXCR4. CXCR4 overexpressing cells expressed higher levels of ITF2B, Contactin-1 and NEDD9 compared to cells with vector alone (Fig. 4C and D). Collectively, microarray results, expression analysis in the presence and absence of CXCL12, knockdown of CXCR4 by siRNA and shRNA experiments and overexpression studies show CXCR4 regulating ITF2B expression but not vice versa, i.e., ITF2B regulating CXCR4 expression.

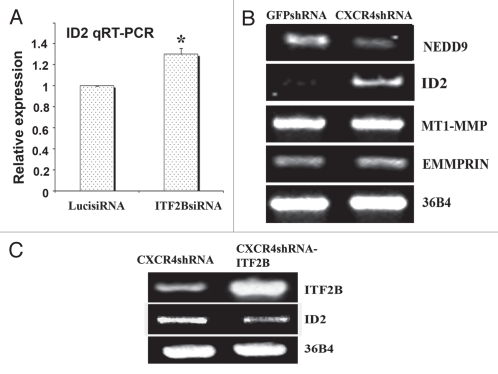

Figure 4.

The effects of CXCR4 knockdown and overexpression on ITF2B expression. (A) qRT-PCR showing CXCR4 and ITF2B expression in CXCR4-enriched cells stably expressing control GFPshRNA, CXCR4shRNA or CXCR4shRNA plus ITF2B. (B) Flow cytometry showing CXCR4 levels in CXCR4-low cells transduced with CXCR4 retrovirus. (C) CXCR4 overexpressing cells show elevated ITF2B. qRT-PCR was used to measure ITF2B expression. (D) CXCR4 overexpression also leads to elevated Contactin-1 and NEDD9.

CXCR4 and ITF2 control ID 2 expression.

The ITF2 function in mammary epithelial cells is intimately linked to ID family, particularly ID2.19 Interestingly, ID2 expression showed a negative correlation with CXCR4 and ITF2B expression in both microarray and in the analysis of MD-231, TMD-231 and LMD-231 cells (Table S1 and Fig. 1D). To analyze whether CXCR4 and ITF2B repress ID2, we examined the effects of CXCR4 and ITF2B manipulation on ID2 expression. Knockdown of ITF2B in CXCR4-enriched cells resulted in elevated expression of ID2 suggesting that ITF2B negatively regulates ID2 (Fig. 5A). ID2 expression was elevated in CXCR4shRNA cells compared to control GFPshRNA cells confirming negative regulation of ID2 by CXCR4 (Fig. 5B). In contrast to ID2, CXCR4shRNA cells expressed lower levels of NEDD9, which suggests that NEDD9 expression is positively regulated by CXCR4. CXCR4shRNA had no effect on the expression of MT1-MMP indicating that elevated expression of this gene in CXCR4-low cells is unrelated to CXCR4 activated signals.

Figure 5.

ID2 is downstream of CXCR4 and ITF2B in TMD-231 cells. (A) Expression of ID2 in luciferase siRNA and ITF2BsiRNA treated cells. ID2 expression was measured by qRT-PCR. *p = 0.02, luciferase siRNA versus ITF2B siRNA treated cells. (B) CXCR4shRNA reduces NEDD9 but increases ID2 expression. (C) ITF2B suppresses ID2 expression in CXCR4shRNA cells.

The role of ITF2 in suppressing ID2 expression was further confirmed in CXCR4shRNA cells with or without ITF2B overexpression (Fig. 5C). These results suggest the presence of CXCR4:ITF2B:ID2 axis in breast cancer cells.

ITF2B is essential for invasiveness of TMD-231 cells.

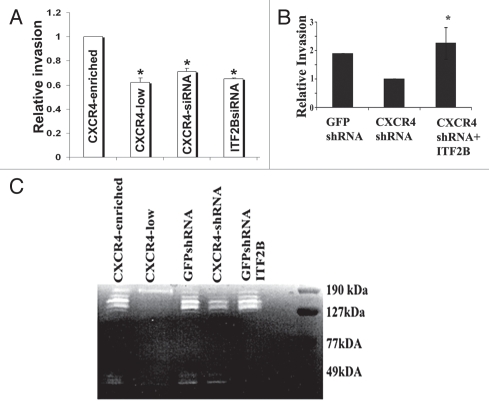

We used matrigel invasion assay to compare invasive properties of CXCR4-enriched, CXCR4-low, CXCR4siRNA-treated and ITF2BsiRNA-treated cells. CXCR4-enriched cells were more invasive compared to CXCR4-low cells (Fig. 6A). CXCR4siRNA and ITF2BsiRNA treated CXCR4-enriched cells exhibited significantly reduced invasion compared to control luciferase siRNA treated cells (Fig. 6A). Thus, invasion of CXCR4-enriched cells through matrigel is dependent on both CXCR4 and ITF2B.

Figure 6.

ITF2B plays a role in invasion of CXCR4-enriched cells. (A) CXCR4siRNA and ITF2BsiRNA reduce the invasion of CXCR4-enriched cells in matrigel invasion assay (left part). *p = 0.02, CXCR4-enriched cells versus other cell types. (B) ITF2B overexpression restores invasive capacity to CXCR4-enriched cells expressing CXCR4shRNA. CXCL12 (100 ng/ml) was added to the bottom chamber in invasion assay. *p = 0.01 CXCR4 shRNA versus CXCR4shRNA-ITF2B. (C) CXCR4 and ITF2B control the expression of ∼130 kDa gelatinase. Conditioned media from indicated cell types were subjected to gelatin zymography. Representative gel from three experiments is shown.

To determine whether ITF2B can restore invasive capacity to CXCR4-enriched cells expressing CXCR4 shRNA, matrigel invasion assay was performed with GFPshRNA, CXCR4shRNA and CXCR4shRNA-ITF2B cells. CXCR4shRNA-ITF2B cells were more invasive than CXCR4shRNA cells with control vector suggesting that ITF2B can functionally replace CXCR4 with respect to invasion (Fig. 6B).

Invasion of cancer cells requires the activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).33 Gelatin zymography with the conditioned media (CM) from CXCR4-enriched, CXCR4-low, GFPshRNA, CXCR4shRNA and CXCR4shRNA-ITF2B cells revealed elevated gelatinase activity around 130 kDa and 45 kDa regions in the CM from CXCR4-enriched and GFPshRNA cells compared to CM from CXCR4-low or CXCR4shRNA cells (Fig. 6C). The gelatinase activity at 45 kDa region may correspond to that of active MMP-13, which has previously been shown to be induced by CXCR4 and is expressed in breast cancer cells.34,35 CM from CXCR4shRNA-ITF2B cells showed 130 kDA gelatinase activities similar to that of GFPshRNA and CXCR4-enriched cells. Thus, ITF2B is likely to be involved in the expression of CXCR4-dependent pro-invasive genes. Identity of the 130 kDa gelatinase is unknown at present but may correspond to a ∼120 kDa gelatinase expressed in mammary epithelial cells in ID1-dependent manner.36

CXCR4-enriched cells form highly metastatic tumors compared to CXCR4-low cells.

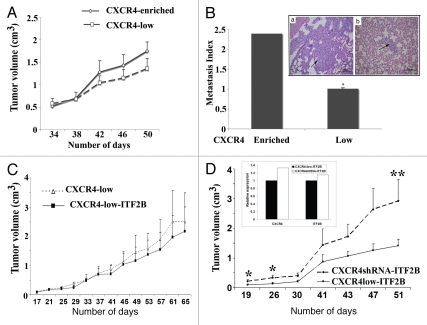

We compared tumor-forming abilities of CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low cells. CXCR4-enriched cells used in these experiments express 3-fold higher levels of CXCR4 and ITF2B compared to CXCR4-low cells (Fig. 1E). In general, CXCR4-enriched cells formed large tumors compared to CXCR4-low cells when implanted into the mammary fat pad of nude mice (Fig. 7A). However, differences did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.06) because animals with CXCR4-enriched cell-derived tumors had to be euthanized for humane reasons after 48 days. We examined whether CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low cell-derived tumors show different degree of lung metastasis. H&E staining and subsequent measurement of metastasis index showed significantly enhanced metastasis of CXCR4-enriched cell-derived tumors compared to CXCR4-low cellderived tumors (p = 0.02, Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Tumorigenic and metastatic properties of CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low cells. (A) Tumorigenic properties of CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low cells. Cells were injected into the mammary fat pad of female nude mice (n = 8 per group) and the tumor volume was measured on indicated days post injection. (B) Lung metastasis index in animals injected with CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low cells. H&E stained lung of a representative animal in both subgroups displaying a region of metastasis (indicated by an arrow) is shown. *p = 0.02, CXCR4-enriched versus CXCR4-low. (C) Tumorigenic properties of CXCR4-low cells with control vector or overexpressing ITF2B (n = 6). (D) Tumorigenic properties of CXCR4-low and CXCR4shRNA cells overexpressing ITF2B. These experiments were done in parallel (n = 6). *p = 0.03; **p = 0.07. Inset shows the expression levels of CXCR4 and ITF2B in two cell types.

ITF2B enhances CXCR4-mediated tumor growth.

We next examined the contribution of ITF2B in tumor growth and metastasis. CXCR4-low cells with control vector or overexpressing ITF2B were injected into the mammary fat pad of nude mice. Surprisingly, ITF2B overexpression alone did not lead to enhanced tumor growth (Fig. 7C). Lung metastasis was also similar with both groups (data not shown). We then compared tumor growth properties of CXCR4-low cells overexpressing ITF2B with CXCR4shRNA cells overexpressing ITF2B by performing xenograft studies at the same time. Note that CXCR4 and ITF2B expression levels in these two cell types were similar (Fig. 7D and inset). Interestingly, tumors appeared earlier and grew at much faster rate in animals implanted with CXCR4shRNA-ITF2B cells compared to animals injected with CXCR4low-ITF2B cells (Fig. 7D). At early timepoints, differences in the rate of tumor growth between two groups were statistically significant and the trend continued till early termination of the experiment due to excessive growth of CXCR4shRNA-ITF2B-derived tumors.

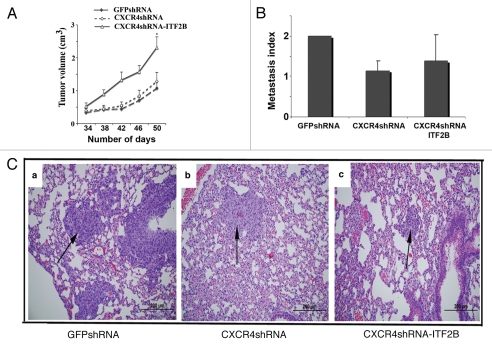

We then examined tumor growth and metastasis properties of GFPshRNA, CXCR4shRNA and CXCR4shRNA-ITF2B cells. CXCR4shRNA-ITF2B cells expressed 30% higher levels of ITF2B compared to GFPshRNA cells and three-fold higher levels of ITF2B compared to CXCR4shRNA cells (see Fig. 4A). CXCR4shRNA-ITF2B cells formed tumors that grew at significantly faster rate than tumors derived from other two cell types suggesting a role for ITF2B in tumor growth (p = 0.01, Fig. 8A). Thus, it appears that ITF2B promotes growth of cells that are originally CXCR4-positive and possibly functions in collaboration with other genes that are co-expressed with CXCR4. Although CXCR4shRNA cell-derived tumors showed reduced levels of metastasis compared to GFPshRNA cell-derived tumors (p = 0.26) and CXCR4shRNA-ITF2B-derived tumors were more metastatic than CXCR4shRNA-derived tumors (p = 0.6), none of these differences were statistically significant (Fig. 8B). A representative H&E staining showing lung metastasis is shown in Figure 8C. We did not attempt to generate stable cell lines with ITF2B shRNA due to general technical difficulties in maintaining shRNA expression for prolonged duration, particularly for in vivo studies. In summation, the above results reveal a role for ITF2B in primary tumor growth under specific cell-type background.

Figure 8.

Tumorigenic and metastasis properties of GFPshRNA, CXCR4shRNA and CXCR4shRNA-ITF2B cells. (A) Rate of tumor growth (n = 8 per group). *p = 0.01 (GFPshRNA or CXCR4shRNA cells versus CXCR4shRNA-ITF2B). (B) Lung metastasis index in GFPshRNA, CXCR4shRNA and CXCR4shRNA-ITF2B cell injected animals. (C) Representative lung metastasis in each group is shown.

Discussion

CXCR4 regulates important processes of tumor progression such as proliferation, angiogenesis, host immune responses against malignant cells and metastasis.37,38 CXCR4-enriched cancer cell subpopulation with distinct biological properties has been identified in breast, prostate and pancreatic cancers.7,20,39 In breast cancer cells, CXCR4 stimulation leads to tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase and cytoskeletal proteins such as paxillin and Crk.40 These events lead to activation of PI3 kinase, MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression and consequently altered cellular architecture and gene expression.40 The transcription factor NF.B is one of the nuclear messengers of CXCR4-activated signals depending on the cell type.41 However, global gene expression changes as a consequence of constitutive CXCR4 activation are yet to be reported. In this study, we present evidence for differential expression of ∼200 genes that correlated with CXCR4 signaling.

MDA-MD-231 cells provided an ideal model system for identifying genes that are linked to CXCR4 signaling because CXCR4 in these cells is constitutively active due to TFF2 expression and only a subpopulation of cells express CXCR4.10,16 These characteristics obviated the need for standardizing concentration and time of exposure to ligands. Recent studies have clearly shown that CXCL12 is not the sole ligand for CXCR4, which makes it even harder to study CXCR4-dependent gene expression changes.15,16

Under the constitutively active condition, CXCR4 signaling directly contributes to some of the gene expression differences between CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low cells. ITF2B, ID2 and NEDD9 are some of the examples. CXCL12 increased ITF2B expression in MDA-MB-361 cells, although the level of induction was of lower magnitude compared to MDA-MB-231 cells; this could possibly be due to lower level of CXCR4 in MDA-MB-361 compared to MDA-MB-231 (data not shown). As there are only few breast cancer cell lines that express significant levels of CXCR4 and MDA-MB-231 among them represent the most aggressive cell line with significant metastatic properties, we restricted our studies to only this cell line. We had previously demonstrated that CXCR4 inhibits the expression of five members of MHC class II family and this inhibition is mediated through the class II transactivator (CIITA).22 CIITA activates as well as represses genes; therefore, modulation of CIITA function by CXCR4 may be responsible for some of gene expression changes in CXCR4-enriched cells.42 Although CXCR4 has been shown to activate NFκB in several cell types43,44 and cytokines that induce NFκB are overexpressed in CXCR4-enriched cells compared to CXCR4-low cells (Table 1), constitutive NFκB DNA binding activity in CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low cells were similar (data not shown). Therefore, NFκB is less likely to be involved in differential expression of genes in CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low cells. CXCR4:CXCL12 induces pro-invasive and pro-survival genes through PI3 kinase/AKT pathway, which may partly contribute to differential expression of genes in CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low cells.45

Among three transcription regulatory proteins elevated in CXCR4-enriched cells (retinoic acid receptor beta, NRIP1 and ITF2), we verified the requirement of CXCR4 for ITF2 expression. ITF2 is expressed as two isoforms: ITF2A and ITF2B. ITF2A heterodimerizes with muscle specific E-box transcription factors such as MyoD to activate gene expression during muscle differentiation, whereas ITF2B heterodimerizes with MyoD to inhibit transcription.46 Majority of breast cancer cell lines that we have examined express higher levels of ITF2B compared to ITF2A (data not shown). Therefore, ITF2B may form transcription repression complex with other E-box binding proteins in CXCR4-positive cells. ITF2B heterodimerizes with ID1 and ID2;47 however, ITF2B:ID1 but not ITF2B:ID2 heterodimers may be predominant in CXCR4-enriched cells because CXCR4 and ITF2B reduced ID2 expression.

ID1 and ID2 have yin-yang relationship in the breast; ID1 prevents differentiation of normal breast and mediates tumor reinitiation and lung metastasis, whereas ID2 is essential for pregnancy-dependent differentiation of breast epithelial cells.36,48,49 Reduced expression of this protein in breast cancer is associated with poor prognosis.50 CXCR4 may tilt the balance in favor of ID1 by repressing ID2. ID1 or ID1:ITF2B complex, which is dominant in CXCR4-enriched cells, may alter the function of a host of bHLH transcription factors. These CXCR4-mediated changes in bHLH transcription factors may have a significant influence on epithelial to mesenchymal transition, a recently described function of ITF2B and consequently invasive phenotype of cancer cells.51 This property of ITF2B may have contributed to higher invasive properties of CXCR4-enriched cells compared to CXCR4-low cells. We were not able to show a role for ITF2B in metastasis in vivo. This could possibly be due to duration of the experiment. We had to terminate the study early because of excessive growth of ITF2B overexpressing cells. Interestingly, ITF2B mediated increase in tumor growth was observed only when it is overexpressed in CXCR4-enriched cells with CXCR4 shRNA but not in CXCR4-low cells (Fig. 7). These results suggest that tumor growth properties of ITF2B is restricted to specific subtype of cancer cells and is dependent on other proteins present in these cells. This is consistent with the results of gene expression analysis of primary tumors; elevated ITF2 expression correlating with poor prognosis mostly in ER-negative breast cancers (Fig. 2). It is likely that primary tumors show heterogeneity in ITF2B expression with focal expression depending on the expression levels of CXCR4, similar to heterogeneity observed in cell lines. Immunohistochemistry with both CXCR4 and ITF2B is essential to test this possibility. Since the function of ITF2 is dependent on the levels of E-box binding proteins including ID family,17 the cell type specific differences in the expression levels of E-box binding proteins may ultimately determine how ITF2 influences tumor growth and invasion. Thus, ITF2B, CXCR4 and E-box proteins may constitute a signaling network in breast cancer; percentage of cancer cells in a tumor with this network may ultimately determine the course of the tumor.

Material and Methods

Cell lines and plasmids.

MDA-MB-231 cells were maintained in MEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) plus insulin (10−9 M). The CXCR4 shRNA and GFP shRNA vector as a control were purchased from Open BioSystems (Huntsville, AL). ITF2B and CXCR4 cDNAs were cloned into the bicistronic retrovirus vector pcQXIN (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). Retroviruses were packaged using Amphophenix cell line. MDA-MB-231 cells were transduced with retroviruses and selected in media containing 750 ng/ml of G418. Recombinant CXCL12 was purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ).

Flow cytometry and microarray.

Details of flow cytometry sorting of CXCR4-enriched and CXCR4-low cells, RNA preparation, microarray and statistical analysis have been described previously.52 The gene expression array data have been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under the accession number GSE15893.

siRNA transfection.

Cells were seeded in MEM plus 10% FBS for 48 h and then transfected with 5 nM of siRNA (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) using Nucleofector reagent (Amaxa Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). Cells were harvested after four days of siRNA transfection and investigated using flow cytometry, RT-PCR and invasion assays.

RT-PCR and quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR).

Independent samples of total RNA were prepared using RNAeasy kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). First strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamers and superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). qRT-PCR was performed using the SyBr green according to the manufacturer's protocol (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). ITF2B expression was also verified using TaqMan probe (Applied Biosciences). Expression of the hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase or β-actin housekeeping genes was used as an internal control for normalization between samples. Sequences of primers used are presented as a supplementary file (Table S3).

Invasion assay.

Cell invasion assay was done using invasion assay kit (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) as described previously.21 Cells were serum starved overnight and then plated on the upper chamber. The lower chamber contained complete medium with or without additional CXCL12.

Mouse mammary fat pad injection, tumor and metastasis measurements.

Cells (106) were injected into the mammary fat pad of 7-week-old female nude mice.53 Tumors started developing after 2–3 weeks of injection. Tumor size was measured twice every week till the termination of the study and expressed as cm3. Tumor and lungs were collected in formalin, stained with H&E and metastasis index was calculated as described previously.53

Gelatin zymography.

Aliquots of serum-free conditioned medium (CM) from equal number of cells were analyzed by gelatin zymography as described previously.54 CM was concentrated 10 folds using Amicon 10 kDa cutoff filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA), loaded without reduction on gels and visualized for activated MMPs.

Analysis of gene expression array databases.

A recently developed database that contains expression levels of 22,277 genes in tumors from 1,809 breast cancer patients and permits survival analysis was used for the generation of Kaplan-Meier curve under various parameters.31 The tumor characteristics and RNA extraction methods used for the microarray analyses are in Table S4.

Statistical analysis.

Experiments were repeated 2–5 times. Results of qRT-PCR were analyzed using GraphPad software (Graphpad.com). Analysis of variance was employed to determine the p-values between mean measurements. A p value of <0.05 was deemed significant. Statistical analysis of metastasis index in different groups was performed using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Error bars on all histograms represent a standard deviation or standard error as indicated between the measurements.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Patricia Steeg (NIH) for MDA-MB-361 cells, H. J. Edenberg and Jeanette McClintick for microarray analysis and Ms. S.E. Rice (IU Simon Cancer Center flow cytometry core) for flow cytometry. We also thank Guo Wang for his help in ingenuity pathway analysis. This work is supported by the grant BCTR0601111 from Susan G. Komen for Cure (to H.N.). H.N. is Marian J. Morrison Professor of Breast Cancer Research.

Abbreviations

- bHLH

basic helix-loop-helix

- CIITA

class ii transactivator

- CM

conditioned media

- CXCR4

chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GEO

gene expression omnibus

- GFP

green fluorescence protein

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- ID

inhibitor-of-differentiation

- IL-1

interleukin 1

- ITF2

immunoglobulin transcription factor 2

- MMPs

matrix metalloproteinases

- NEDD9

neural precursor cell expressed developmentally downregulated gene 9

- NFκB

nuclear factor kappaB

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- SDF1α

stromal cell-derived factor-1α

- shRNA

small hairpin RNA

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TFF2

trefoil factor 2

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cbt/article/12586

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Eccles SA, Welch DR. Metastasis: recent discoveries and novel treatment strategies. Lancet. 2007;369:1742–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60781-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steeg PS. Tumor metastasis: mechanistic insights and clinical challenges. Nat Med. 2006;12:895–904. doi: 10.1038/nm1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:540–550. doi: 10.1038/nrc1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sgroi DC, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Delaunay T, Naeem R, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, et al. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410:50–56. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salvucci O, Bouchard A, Baccarelli A, Deschenes J, Sauter G, Simon R, et al. The role of CXCR4 receptor expression in breast cancer: a large tissue microarray study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;97:275–283. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang Y, Siegel PM, Shu W, Drobnjak M, Kakonen SM, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. A multigenic program mediating breast cancer metastasis to bone. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:537–549. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li YM, Pan Y, Wei Y, Cheng X, Zhou BP, Tan M, et al. Upregulation of CXCR4 is essential for HER2-mediated tumor metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinton CV, Avraham S, Avraham HK. Role of the CXCR4/CXCL12 signaling axis in breast cancer metastasis to the brain. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;27:97–105. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9210-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helbig G, Christopherson KW, 2nd, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Kumar S, Kishimoto H, Miller KD, et al. NFkappaB promotes breast cancer cell migration and metastasis by inducing the expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21631–21638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang Z, Yoon Y, Votaw J, Goodman MM, Williams L, Shim H. Silencing of CXCR4 blocks breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:967–971. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith MC, Luker KE, Garbow JR, Prior JL, Jackson E, Piwnica-Worms D, et al. CXCR4 regulates growth of both primary and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8604–8612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kishimoto H, Wang Z, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Chang D, Clarke R, Nakshatri H. The p160 family coactivators regulate breast cancer cell proliferation and invasion through autocrine/paracrine activity of SDF-1{alpha}/CXCL12. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1706–1715. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akekawatchai C, Holland JD, Kochetkova M, Wallace JC, McColl SR. Transactivation of CXCR4 by the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) in human MDA-MB-231 breast cancer epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39701–39708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509829200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernhagen J, Krohn R, Lue H, Gregory JL, Zernecke A, Koenen RR, et al. MIF is a noncognate ligand of CXC chemokine receptors in inflammatory and atherogenic cell recruitment. Nat Med. 2007;13:587–596. doi: 10.1038/nm1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubeykovskaya Z, Dubeykovskiy A, Solal-Cohen J, Wang TC. Secreted trefoil factor 2 activates the CXCR4 receptor in epithelial and lymphocytic cancer cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:3650–3662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804935200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perk J, Iavarone A, Benezra R. Id family of helix-loop-helix proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:603–614. doi: 10.1038/nrc1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolligs FT, Nieman MT, Winer I, Hu G, Van Mater D, Feng Y, et al. ITF-2, a downstream target of the Wnt/TCF pathway, is activated in human cancers with beta-catenin defects and promotes neoplastic transformation. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parrinello S, Lin CQ, Murata K, Itahana Y, Singh J, Krtolica A, et al. Id-1, ITF-2 and Id-2 comprise a network of helix-loop-helix proteins that regulate mammary epithelial cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39213–39219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hermann PC, Huber SL, Herrler T, Aicher A, Ellwart JW, Guba M, et al. Distinct populations of cancer stem cells determine tumor growth and metastatic activity in human pancreatic cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehta SA, Christopherson KW, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Goulet RJ, Jr, Broxmeyer HE, Kopelovich L, et al. Negative regulation of chemokine receptor CXCR4 by tumor suppressor p53 in breast cancer cells: implications of p53 mutation or isoform expression on breast cancer cell invasion. Oncogene. 2007;26:3329–3337. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheridan C, Sadaria M, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Goulet R, Jr, Edenberg HJ, McCarthy BP, et al. Negative regulation of MHC class II gene expression by CXCR4. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:1085–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Neill GM, Seo S, Serebriiskii IG, Lessin SR, Golemis EA. A new central scaffold for metastasis: parsing HEF1/Cas-L/NEDD9. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8975–8979. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson KJ, Selfors LM, Bui J, Reynolds A, Leake D, Khvorova A, et al. Identification of genes that regulate epithelial cell migration using an siRNA screening approach. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1027–1038. doi: 10.1038/ncb1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yee KO, Connolly CM, Duquette M, Kazerounian S, Washington R, Lawler J. The effect of thrombospondin-1 on breast cancer metastasis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;114:85–96. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9992-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Podhajcer OL, Benedetti L, Girotti MR, Prada F, Salvatierra E, Llera AS. The role of the matricellular protein SPARC in the dynamic interaction between the tumor and the host. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:523–537. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koblinski JE, Kaplan-Singer BR, VanOsdol SJ, Wu M, Engbring JA, Wang S, et al. Endogenous osteonectin/SPARC/BM-40 expression inhibits MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7370–7377. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu M, Yao J, Carroll DK, Weremowicz S, Chen H, Carrasco D, et al. Regulation of in situ to invasive breast carcinoma transition. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:394–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, et al. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dontu G, Abdallah WM, Foley JM, Jackson KW, Clarke MF, Kawamura MJ, et al. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1253–1270. doi: 10.1101/gad.1061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gyorffy B, Lanczky A, Eklund AC, Denkert C, Budczies J, Li Q, et al. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:725–731. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu QD, Ang BT, Karsak M, Hu WP, Cui XY, Duka T, et al. F3/contactin acts as a functional ligand for Notch during oligodendrocyte maturation. Cell. 2003;115:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00810-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Page-McCaw A, Ewald AJ, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:221–233. doi: 10.1038/nrm2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohrmann A, Kammerer U, Kapp M, Dietl J, Anacker J. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in primary human breast cancer and breast cancer cell lines: New findings and review of the literature. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:188. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan CT, Chu CY, Lu YC, Chang CC, Lin BR, Wu HH, et al. CXCL12/CXCR4 promotes laryngeal and hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma metastasis through MMP-13-dependent invasion via the ERK1/2/AP-1 pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1519–1527. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Desprez PY, Lin CQ, Thomasset N, Sympson CJ, Bissell MJ, Campisi J. A novel pathway for mammary epithelial cell invasion induced by the helix-loop-helix protein Id-1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4577–4588. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kucia M, Reca R, Miekus K, Wanzeck J, Wojakowski W, Janowska-Wieczorek A, et al. Trafficking of normal stem cells and metastasis of cancer stem cells involve similar mechanisms: pivotal role of the SDF-1-CXCR4 axis. Stem Cells. 2005;23:879–894. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corcoran KE, Trzaska KA, Fernandes H, Bryan M, Taborga M, Srinivas V, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells in early entry of breast cancer into bone marrow. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:2563. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miki J, Furusato B, Li H, Gu Y, Takahashi H, Egawa S, et al. Identification of putative stem cell markers, CD133 and CXCR4, in hTERT-immortalized primary nonmalignant and malignant tumor-derived human prostate epithelial cell lines and in prostate cancer specimens. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3153–3161. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandis AZ, Prasad A, Band H, Klosel R, Ganju RK. Regulation of CXCR4-mediated chemotaxis and chemoinvasion of breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:157–167. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ganju RK, Brubaker SA, Meyer J, Dutt P, Yang Y, Qin S, et al. The alpha-chemokine, stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha, binds to the transmembrane G-protein-coupled CXCR-4 receptor and activates multiple signal transduction pathways. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23169–23175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sengupta P, Xu Y, Wang L, Widom R, Smith BD. Collagen alpha1(I) gene (COL1A1) is repressed by RFX family. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21004–21014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413191200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alvarez S, Blanco A, Fresno M, Munoz-Fernandez MA. Nuclear factor-kappaB activation regulates Cyclooxygenase-2 induction in human astrocytes in response to CXCL12: Role in neuronal toxicity. J Neurochem. 2010;113:772–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang CY, Lee CY, Chen MY, Yang WH, Chen YH, Chang CH, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4 enhanced motility of human osteosarcoma cells involves MEK1/2, ERK and NFkappaB-dependent pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2009;221:204–212. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peng SB, Peek V, Zhai Y, Paul DC, Lou Q, Xia X, et al. Akt activation, but not extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation, is required for SDF-1alpha/CXCR4-mediated migration of epitheloid carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:227–236. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-04-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skerjanc IS, Truong J, Filion P, McBurney MW. A splice variant of the ITF-2 transcript encodes a transcription factor that inhibits MyoD activity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3555–3561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Itahana Y, Piens M, Fong S, Singh J, Sumida T, Desprez PY. Expression of Id and ITF-2 genes in the mammary gland during pregnancy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372:826–830. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miyoshi K, Meyer B, Gruss P, Cui Y, Renou JP, Morgan FV, et al. Mammary epithelial cells are not able to undergo pregnancy-dependent differentiation in the absence of the helix-loop-helix inhibitor Id2. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:2892–2901. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gupta GP, Perk J, Acharyya S, de Candia P, Mittal V, Todorova-Manova K, et al. ID genes mediate tumor reinitiation during breast cancer lung metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19506–19511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709185104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stighall M, Manetopoulos C, Axelson H, Landberg G. High ID2 protein expression correlates with a favourable prognosis in patients with primary breast cancer and reduces cellular invasiveness of breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:403–411. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sobrado VR, Moreno-Bueno G, Cubillo E, Holt LJ, Nieto MA, Portillo F, et al. The class I bHLH factors E2-2A and E2-2B regulate EMT. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1014–1024. doi: 10.1242/jcs.028241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheridan C, Kishimoto H, Fuchs RK, Mehrotra S, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Turner CH, et al. CD44+/CD24− breast cancer cells exhibit enhanced invasive properties: an early step necessary for metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:59. doi: 10.1186/bcr1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sweeney CJ, Mehrotra S, Sadaria MR, Kumar S, Shortle NH, Roman Y, et al. The sesquiterpene lactone parthenolide in combination with docetaxel reduces metastasis and improves survival in a xenograft model of breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1004–1012. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar S, Kishimoto H, Chua HL, Badve S, Miller KD, Bigsby RM, et al. Interleukin-1alpha promotes tumor growth and cachexia in MCF-7 xenograft model of breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2531–2541. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63608-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.