Synopsis

The electrophysiological properties of the sleeping brain profoundly influence memory function in various species, yet the molecular nature by which sleep and memory interact remains unclear. We summarize work that has established the cAMP-PKA-CREB intracellular signaling pathway as a major mechanism involved in the wakeful consolidation of memory in many organisms while highlighting newer evidence that this pathway has a role in sleep regulation, sleep deprivation and potentially sleep-memory interactions. We explore the possibility that sleep might influence memory processing by reactivating the same molecular cascades first recruited during learning during a sort of “molecular replay”. Lastly, we discuss how new approaches together with established techniques will aid in our understanding of the nature of sleep-memory interactions.

Keywords: cAMP, PKA, CREB, learning, memory, NREM, REM, oscillation

I. Introduction

The “sleep-for-memory” hypothesis has gained considerable momentum in response to a growing body of literature detailing the beneficial effects of sleep on memory function. Indeed, memory function from humans to flies appears to benefit from, if not depend on, some core property of sleep. Over time, sleep has been proposed to serve a variety of functions 120. However, it has been argued that the core function of sleep is likely cellular since the function of proteins from membrane receptors to transcription factors are remarkably consistent across phylogenetic lines, as is the need for sleep, regardless of differences in sleep architecture and brain complexity 21. The sleep-for-memory hypothesis posits that a primary cellular function of sleep is memory consolidation, the process by which newly acquired information is stabilized and stored. Like the need for sleep, the molecular mechanisms that mediate memory consolidation are also conserved across species. Although little is known about the molecular mechanisms mediating sleep-dependent memory processing, there is evidence to suggest that wakeful experience is recapitulated during sleep, suggesting, by extension, that the same molecular processes that promote memory consolidation might be re-engaged during sleep to further stabilize and improve memory.

Here we present several key concepts and molecular processes that are known to underlie learning and memory consolidation. We then give an overview of some the electrophysiological events specific to various sleep states that might serve to modulate activity within these signaling pathways. We address recent progress, questions still unanswered, and the challenges and limitations associated with the methodologies used to study sleep-memory interactions on a molecular level.

II. Stages of memory processing

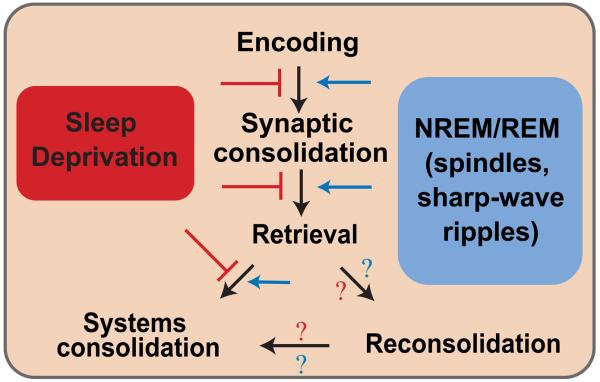

Memory storage is often differentiated into pharmacologically dissociable stages 1. During the encoding or acquisition phase, perceived information is transformed into synaptic activity through the propagation of electric and chemical signals between neurons at synapses. Changes in synaptic activity resulting from the encoding process must be stabilized or consolidated if they are to become part of an enduring memory. The consolidation process can be further distinguished into three forms: synaptic consolidation, which occurs soon after acquisition or encoding; systems consolidation, whereby memory is reorganized throughout the brain over weeks to years; and reconsolidation which is a stabilization process that can occur after the retrieval of a memory. Often, multiple sessions or trials are required to form a particular association and related memory. Therefore, memory of those associations might involve multiple iterations of acquisition, consolidation and reconsolidation. In this way, sleep could potentially influence multiple stages of memory processing (see Figure 1) 170. Here we review some of the key molecular events involved in each stage of learning and memory formation with the idea that some or all of the processes described below could potentially be re-engaged during sleep-dependent memory processing. The reader is also referred to Figure 2 for a schematic of the molecular pathways involved in memory consolidation.

Fig. 1. Permissive and inhibitory effects of sleep and sleep deprivation on the stages of memory formation.

Encoding allows relevant environmental information to be converted into a neural construct that can be stored within the brain and recalled at a later time. Newly learned information must be stabilized by strengthening and stabilizing synapses that were activated during learning. Once consolidated, memory can be retrieved and used by the organism. Under certain conditions, retrieved memories render them sensitive to disruption, requiring them to undergo the process of reconsolidation. Reconsolidated and previously learned memories may also be consolidated on a systems level. Systems consolidation typically refers to the reorganization or transference of memory traces out of the hippocampus to areas in the neocortex. Sleep-dependent processing of memory has been shown in impact all stages of memory formation. Neural oscillations during NREM and REM sleep have permissive, enhancing effects on each stage of memory formation (depicted with blue arrows), whereas sleep-deprivation or the prevention of sleep-related oscillations impairs memory formation (shown with red lines). The role of sleep and sleep deprivation in reconsolidation is less understood and is denoted with question marks.

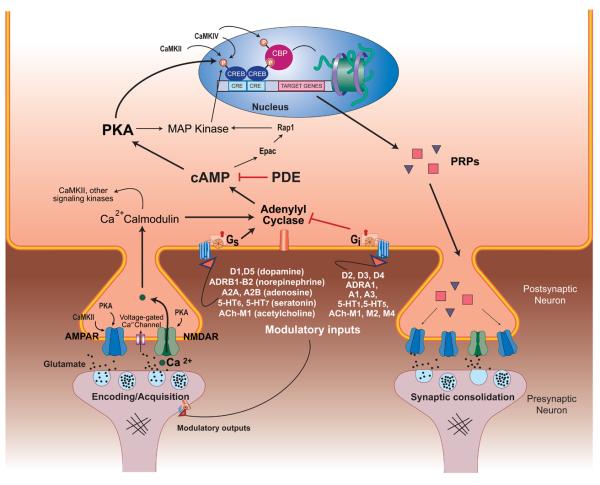

Fig. 2. Signaling pathways involved in the encoding and consolidation of learning and memory.

During encoding, presynaptic release of glutamate activates NMDA and AMPA-Rs in the postsynaptic cell (synapse shown on the left). Ca2+ influx through these receptors and through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels activates Ca2+-calmodulin which can activate CaMKII, PKA and others, which can then increase AMPA and NMDA receptors through the phosphorylation of various receptor subunits. Long-term memory formation requires transcription and translation dependent mechanisms in order to strengthen and stabilize synaptic connectivity. Ca2+ influx during encoding can activate adenylyl cyclase (AC) which increases intracellular levels of the second messenger cAMP. Increased cAMP levels upregulate PKA-dependent phosphorylation of other protein kinases (e.g., the MAP kinases) which, together with PKA, can translocate to the nucleus to activate the transcription factor CREB. cAMP also activates Epac98, although the role of Epac in sleep-related plasticity has not been investigated. Other signaling proteins such as CAMKIV and CAMKII2,19,37,75,86,104,173,175 also play a role in CREB activation. CREB together with its coactivator CBP (and others) regulate gene transcription by promoting the binding of transcriptional machinery to target genes and by making target genes more accessible to transcriptional machinery by altering chromatin structure9,12,18,45,57,77,134,165. Proteins synthesized in the soma or locally in dendrites 152 are transported to synapses that have been tagged by prior activity. AMPA-R trafficking into the post-synaptic membrane (shown in the synapse on the right) plays an important role in the long-term maintenance of synaptic strength. Importantly, cAMP signaling can be regulated by the actions of neurotransmitters that bind to G protein-coupled receptors. Levels of modulatory neurotransmitters, many of which are coupled to both Gs- and Gi-coupled receptors, change dramatically during the sleep-wake cycle. Activation of Gs- and Gi-coupled receptors stimulate and inhibit AC activity, respectively, which alters cAMP production accordingly 1. Sleep deprivation and circadian rhythms can also alter intracellular levels of cAMP, MAPK and other plasticity-associated molecules 35,164.

Acquisition/Encoding

Many neurotransmitters systems are involved in the encoding process, but the study of glutamate-mediated transmission of information through α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPA-R) and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDA-R), has occupied center stage in the study of learning and memory and its cellular correlate, long-term potentiation (LTP, discussed below) 87,119. Transduction of environmental information through glutamate and other modulatory receptors triggers transcriptional and translational mechanisms that mediate gene expression, synaptic plasticity and ultimately behavior. Specifically, Ca2+ influx through glutamate receptors can trigger the covalent modification (e.g., phosphorylation) of pre-existing proteins at active synapses 67,135 resulting in short-term changes in synaptic strength. These short-term changes, along with changes in the presynaptic neuron, alter the probability of the post-synaptic neuron firing to future stimuli. As shown in Figure 2, activity-dependent increases in intracellular Ca2+ levels can activate Ca2+-calmodulin which can then activate calmodulin dependent protein kinase, (CaMKII) and protein kinase A (PKA). CaMKII and PKA can then phosphorylate AMPA and NMDA-R subunits thereby altering synaptic transmission. This increase in receptor function is temporary and allows information to be conveyed in the short term. Short-term memory can then be committed to long-term memory (LTM) or forgotten as the synaptic connections eventually weaken.

Two main theories have been proposed to explain how sleep might influence learning and memory formation. The “active systems” theory proposes that cellular activity observed during learning is replayed or recapitulated in some form during post-learning sleep 82,174. Cellular replay during sleep could mimic the encoding process or help to link new memories to previously consolidated memory networks. According to the “synaptic homeostasis” hypothesis 157, the net strength of synapses increase during wake and are downscaled during sleep. Indeed, AMPA-R subunit phosphorylation has been shown to be higher during wake and lower after sleep in the cortex and hippocampus of rats 166 (but see 60). The elimination of synapses that have only undergone weak encoding, and are not needed for LTM formation, could reduce the “signal to noise” ratio in the brain and allow the encoding of new information to proceed more efficiently. Both theories cite mechanisms that could impact encoding and memory processing and are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Synaptic consolidation

Gene transcription and translation is required for the consolidation of LTM (reviewed in 67) and for the maintenance of LTP 131, the long-lasting enhancement of signal transmission between neurons at synapses that have been repeatedly stimulated. Like STM and LTM, LTP can be distinguished into at least two forms: early (E-LTP) and late (L-LTP) where L-LTP requires transcription and translation. An important aspect of L-LTP is the maintenance of increased synaptic strength brought about by the trafficking of AMPA-Rs containing the GluR1 subunit to the appropriate synapses. Conversely, the strength of synapses can also be decreased during synaptic depression by the removal of AMPA-Rs from the synapse 22,99. This balance between potentiation and depression, or plasticity, is generally thought of as the basis of memory formation 113. Indeed, the study of LTP has contributed a great deal to our understanding of the cellular and molecular biology of learning and memory and is becoming an important tool in understanding sleep-memory interactions 10,97,131.

Increases in intracellular Ca2+ also play a critical role in plasticity-associated transcription and translation. Ca2+ influx stimulates the production of the second messenger 3′-5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) by adenylyl cyclase. cAMP activates at least three targets important in memory processing: PKA, exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac), and hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (HCN) channels (see 4 for review). Once activated, PKA and other plasticity-associated kinases (e.g., MAP kinase, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), CaMKII and CaMKIV 37,104) can phosphorylate and activate the transcription factor cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) which, together with its co-activators regulate, plasticity-associated gene transcription 2,124,132,133 cAMP can also activate Epac, which through Rap1 and other targets, can promote memory formation possibly through CREB activation 52,98. Plasticity-related gene products (PRPs) are translated and targeted to previously activated synapses that require stabilization. Protein synthesis occurring locally in the dendrites can also be regulated by calcium influx through NMDA receptors, and has been shown to play an important role in memory formation 17.

At least one round of transcription- and translation-dependent consolidation is required to stabilize a new memory. However, Bourtchouladze, et. al. 12 and others 18,45,57, have shown that, depending on the training protocol used, two or more waves of PKA activation and protein synthesis are required after training 9,77,134. The exact nature of these waves of activity is unknown but their existence suggests that some sort of feedback or cyclical activity occurs during the post-training time – a time when the experimental subjects were likely sleeping.

Fluctuations in the levels of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters that occur during sleep and extended wakefulness can have important influences on memory consolidation (see 58,96 for recent reviews). For example, sleep-dependent fluctuations of neurotransmitters that bind to G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) can stimulate or inhibit adenylyl cyclase to modulate cAMP levels (see Figure 2). Dopamine and acetylcholine levels are known to vary dramatically during different sleep stages and can activate both stimulatory and inhibitory GPCRs. Thus, the overall neuromodulatory effect of sleep-related neurotransmission may also depend on brain region-specific expression patterns of a particular GPCR. Extended wakefulness and sleep deprivation can also increase levels of adenosine which decreases cAMP by binding Gi-coupled GPCRs. In addition, sleep deprivation can increase levels of phosphodiesterase, the enzyme responsible for degrading cAMP, although the mechanism of this increase is still under investigation 164.

So how might neurons keep a “record” of which synapses out of thousands should be strengthened and maintained? This could be an even bigger problem during sleep when we are unable to intentionally rehearse information. Restated from a molecular level perspective, how does encoding at a particular synapse instruct the cell to deliver the required PRPs resulting from gene transcription and translation to a particular synapse? To solve this problem, it was proposed that encoding triggers the production or delivery of molecular “tags” at synapses activated during learning, providing an “address” to facilitate the delivery of PRPs 46,114. Evidence of synaptic tagging was first demonstrated in various neuronal preparations 47,48,102,103 and has been tied to CREB- and transcription-dependent mechanisms 103,125 and to A kinase-anchoring proteins (AKAPs), that serve to compartmentalize PKA in functionally distinct regions of the neuron 71. The identity of the tag(s) and specific PRPs remain, for the most part, unknown. However, Homer1a has been proposed to fulfill most criteria of a potential tag 117 and is upregulated in mice after sleep deprivation suggesting there may be a connection between the overall level of activated synapses and tag expression with extended wakefulness 100. PKMzeta is also thought to be a PRP that plays a role in the maintenance of L-LTP and memory 139,177. Indeed, any of the cellular machinery involved in local translation might serve as a tag. Importantly, a behavioral correlate of tagging has recently been described 109 where weak inhibitory avoidance training in rats, which does not normally produce LTM for the event, can be consolidated into LTM by exposure to a novel environment. This conversion requires protein synthesis and dopamine (D1/D5) receptor activity. In light of these findings, tagging might be a method by which PRPs mobilized during post-learning wake and sleep are targeted to the appropriate synapses.

Because bouts of sleep occurring soon after learning enhance memory (reviewed in 169), it appears that sleep benefits synaptic consolidation in particular. Sleep can improve speed and reduce errors in motor performance tasks or in word recall tasks 50,106. Whether these benefits are conferred by sleep-specific molecular pathways or boost activity in molecular pathways already activated during wakeful consolidation is not fully understood. The fact that sleep-specific gene expression has been demonstrated could argue for former possibility, but it does not exclude the latter. That is, sleep-dependent gene expression in addition to sleep-dependent modulation of gene expression initiated during learning could occur in parallel.

Systems consolidation

Once consolidated on a synaptic level, newly formed memories undergo a process of reorganization on a broader, systems level. Systems consolidation traditionally refers to the slow transference of memory out of the hippocampus to the neocortex for permanent storage 25,44,151, but more current views include mechanisms by which new memories are incorporated into distributed networks of previously consolidated memories 128. Further, it has been cited that some memories always remain hippocampus dependent and that others have never resided there, stressing the notion that the neocortex is likely more involved during early consolidation than previously appreciated 161,172. These theories are beginning to bridge the events that occur during synaptic consolidation to those classically defined as systems consolidation 25, incorporating a role of sleep in both processes.

The sleep-for-memory hypothesis also posits that sleep, in addition to enhancing encoding and synaptic consolidation, promotes the reorganization of memory during systems consolidation. Pharmacological studies of the function of sleep in systems consolidation are difficult to perform due to the long time-course of memory reorganization and the distributed nature of memory traces, but genetic studies in mice 112 and human imaging studies appear to be consistent with a role for sleep in systems consolidation. Using a declarative word-pair learning task, Gais et al. 49 showed that sleep after learning increased functional connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus during retrieval tests 48 hrs later and enhanced activity in prefrontal cortex during retrieval 6 months later. Sleep-dependent shifts to neocortical-based memory representations could result in more efficient retrieval 128,155. A recent functional MRI study conducted by Orban et al. 118 also demonstrates that sleep promotes the reorganization of brain activity over long periods of time. The authors trained human subjects in a place-finding navigational task; those that slept after training tended to use an extended hippocampo-neocortical network to perform the task in early retrieval sessions and striatal regions in later sessions. However, subjects that were sleep deprived showed significantly less striatal activity during later retrieval tests, suggesting sleep deprivation altered the normal course of memory reorganization over time. Interestingly, performance between the two groups was unaltered, demonstrating that the reorganization of memory between systems does not always enhance performance in learning and memory tasks but can reflect the transference of well-learned information to systems designed to process automated behaviors.

Retrieval and Reconsolidation

Retrieval refers to the reactivation of memory traces. Under certain conditions, retrieval of a memory trace renders it sensitive to disruption by amnesic treatments for a short period of time 55,107,137. Such sensitized memories require “reconsolidation,” during which the retrieved memories undergo further consolidation to be restabilized and stored. Reconsolidation could be a mechanism by which older memories are update and crosslinked with newly formed memories 92. Although, much less is known about the molecular events underlying retrieval and reconsolidation, they appear to have unique molecular signatures involving specific molecular pathways and brain regions 93,111,127. However, PKA activity appears to be a consistent requirement for the retrieval and reconsolidation of many forms of memory, at least in some brain regions 105,110. For example, retrieval of 1-trial inhibitory avoidance memory requires the activation of AMPA and NMDA-Rs in addition to PKA and ERK in the hippocampus and cortex. However, in the amygdala, only AMPA-R activity is required for retrieval; NMDA-R activity, PKA and ERK are unnecessary 8,80,81. Although reconsolidation has been demonstrated in humans 167 there has been much debate on the boundary conditions that dictate whether reconsolidation of a retrieved memory occurs 160 and if amnesia related to the blockade of reconsolidation reflects memory erasure or impaired retrieval 111. The effect of sleep on retrieval and reconsolidation has been less studied, but sleep may affect the reorganization of memories that undergo reconsolidation (see 128,148 for more detailed reviews on the role of sleep in memory reactivation and reconsolidation) and REM sleep deprivation impairs the retrieval of discriminative avoidance training in rats 3.

Summary of Part I

Memory traces instantiated during wake appear to be altered in a sleep-dependent fashion. Sleep occurring within several hours of training, can improve performance in a variety of memory tasks and induce changes in retrieval-associated brain activity 40,171, suggesting that the neuronal substrates of memory are redistributed during sleep 30. Initial studies suggest that sleep-dependent plasticity, much like the initial encoding and consolidation of memory, requires the activation of NMDA-Rs, AMPA-Rs, and PKA 6,42,43,50. Synaptic tagging and multiple waves of intracellular activity might guide and induce the sleep-related strengthening of memories, respectively. However, it is not entirely clear whether sleep-dependent plasticity is controlled by cellular and molecular events that precede sleep, in a sense priming the trace for further modification during sleep, or whether sleep acts more or less independently on memory. Thus, a primary goal from a molecular standpoint is to determine how the unique properties of the sleeping brain might tap into the molecular mechanisms known to instantiate memories during wake. Below we examine how sleep might interact with the molecular pathways involved in memory consolidation.

II. Sleep states and memory

In many organisms, sleep can be broadly characterized as fluctuating between two states: rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and non-rapid-eye movement (NREM) sleep 89 and each of these states may contribute differentially to memory consolidation 130. Several fundamental oscillatory patterns can be seen in the EEG during wake and sleep, including delta (< 1.0-4 Hz), theta (4-9 Hz), beta (15-35 Hz) and gamma (>40 Hz) oscillations 76. During wake, low-amplitude, high frequency gamma oscillations can be observed throughout the cortex69,146 but as the brain transitions from wake to NREM sleep (which has four stages in humans), gamma oscillations give way to the characteristic high amplitude, low-frequency slow waves (<4 Hz) of NREM sleep 144. During REM sleep, rapid desynchronous gamma oscillations are obvious in the cortical EEG as are oscillations in the theta frequency 15,156,162 which are similar to theta rhythms observed during exploratory movements performed during wake 7,13,59,74,116. REM sleep is further characterized by the presence of muscle atonia except for eye and whisker movements in humans and rodents, respectively 5,27,28,84.

Several approaches have been traditionally used to study sleep-memory interactions. As illustrated above, sleep deprivation has been a useful tool but can produce unintended effects on learning and memory as it can be quite stressful on the organism. A second approach correlates sleep-related oscillations (e.g., their duration, frequency, phase and power) to gains in task performance. A third approach examines how learning alters subsequent sleep architecture and EEG patterns. Newer approaches attempt to alter or prevent the occurrence of specific oscillatory rhythms during sleep to provide more direct evidence of sleep-memory interactions. In the following sections, we further examine how oscillatory patterns characteristic to NREM and REM sleep might influence plasticity-associated signaling pathways which are summarized in Figure 2. We also discuss how homeostatic and circadian control of sleep states might influence sleep-memory interactions on a molecular level.

NREM and memory

During NREM sleep, slow-wave oscillations in the delta frequency and specialized oscillations known as sleep spindles (11-15 Hz) 115,136 and sharp wave-ripple (SPW-R) complexes (140-200 Hz) can be observed in the hippocampus and neocortex 14,116,178. Spindle activity during stage II NREM appears to correlate well with improvements in memory tasks (see 26 for a detailed review on sleep spindles). Stages III and IV constitute deep sleep and are collectively referred to as slow wave sleep (SWS). Slow waves reflect the synchronous transitions between “up states” during which neurons of the cortex and hippocampus are collectively depolarized and fire together, and “down states” during which they are hyperpolarized and relatively silent 79. Indeed, evidence suggests that spindles and SPW-Rs play a particularly important role in sleep-memory interactions29,70 and tend to occur together during SWS 38,108,140,141 This temporal coherence is thought to reflect the coordinated transfer of information between the hippocampus and neocortex 126,140, however the exact nature of this hippocampal-neocortical “dialogue” is not fully understood on a cellular or molecular level 158,29,147. Interestingly, the sequence in which specific neurons (e.g., place cells in the hippocampus) are activated during wake appears to be recapitulated, or “replayed,” in various forms during subsequent periods of wake 90, NREM (in particular during SPW-R events 90,174), and REM sleep 174. Furthermore, blockade of hippocampal output in genetically modified mice impaired systems consolidation and reduced the frequency of hippocampal ripples and experience-dependent, ripple-associated reactivation of hippocampal cell pairs 112.

In light of evidence demonstrating that sequences of neuronal activation seen during learning reoccur during post-learning periods of wake and sleep, it is tempting to hypothesize that there is an ensuing period of “molecular replay” when molecular events engaged during learning are re-engaged during sleep. Several studies support the notion that signaling pathways mediating hippocampal long-term plasticity must be reactivated to consolidate memory, perhaps even for its maintenance as a ‘remote’, cortex-dependent memory trace 9,24,138,159.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence that sleep-associated oscillations influence memory processing has been obtained from studies in which oscillations have been either ehanced or inhibited after learning. Marshall et al. used transcranial electrical stimulation in humans to stimulate SWA during NREM sleep after learning in two different hippocampus-dependent tasks or two procedural motor skill tasks 101. Stimulation with slow, 0.75 Hz oscillations during early night NREM sleep selectively enhanced memory retention in the hippocampus-dependent tasks and increased slow wave sleep, as well as endogenous cortical slow oscillations and spindle activity in the frontal cortex, providing the most direct evidence of a role for sleep-associated oscillatory rhythms in memory. Stimulation at 5 Hz or at 0.75 Hz late in the night had no enhancing effect relative to sham stimulation. Interestingly, although memory for the procedural tasks benefitted from sleep in general, no further gains were observed with slow-wave stimulation. Another recent study examined the effect of suppression of SPW-R complexes in rats trained in a hippocampus-dependent spatial-reference memory task using the radial arm maze 54. SPW-R events blocked by stimulation of the ventral hippocampal commissure during post-learning rest and sleep significantly impaired performance relative to rats that received the same number of stimulations but that had intact SPW-R events. Lastly, it has been demonstrated that re-exposure to olfactory cues during SWS, that were part of a training context in a prior learning task, was found to enhance subsequent memory 129. Thus, the type and timing of oscillations during NREM sleep appear to play an important role in sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Despite advances in our understanding of sleep-memory interactions on an electrophysiological level and of the molecular biology of LTM formation, little direct evidence exists to link sleep-related oscillations with memory processing on a molecular level.

REM and memory

During REM sleep, brain activity in the gamma and theta frequency range is similar to that during wake 94,145, but the body is paralyzed due to atonia; for this reason, REM is often referred to as paradoxical sleep. Interestingly, REM sleep deprivation can result in memory impairments; however the degree of impairment appears to be determined by the complexity of the task. Indeed, simple tasks (e.g., passive avoidance, one-way active avoidance and simple mazes), which are quickly learned, are less affected by REM sleep deprivation. Conversely, tasks which require more complex associations to be learned (e.g., discriminative and probabilistic learning, complex maze learning and instrumental conditioning) are particularly sensitive to REM sleep deprivation 66,123. Furthermore, REM sleep deprivation is effective only if the animal has reached a certain level of learning 34,66. In humans, the amount of REM sleep late in sleep cycle (and NREM sleep early in the night) correlates with improvements on a visual discrimination tasks 149. Similar results have been found in a number of tasks and species and have been recently reviewed in detail elsewhere 29,70.

On a molecular level, little is known of the effects of REM sleep on memory processing. REM sleep deprivation, however, has been linked to lower binding of noradrenaline to alpha-and beta-adrenergic receptors throughout the brain 68 which could result in memory impairments by lowering cAMP via decreased Gs stimulation of adenylyl cyclase. REM sleep deprivation has also be been linked to lower levels of phosphorylated CREB and deprivation of both NREM and REM for 5 hrs has recently been shown to produce decreased cAMP signaling in the hippocampus accompanied by impairments in the consolidation of contextual fear memory in mice 164. Thus, cAMP-related signaling appears to also play a role in the effects of REM sleep deprivation on memory consolidation.

III. Homeostatic and circadian control of sleep-dependent memory processing

To understand sleep-memory interactions, we must also understand how sleep and synaptic plasticity are regulated by homeostatic and circadian processes. The homeostatic regulation of sleep can be seen in increased levels of adenosine during sleep deprivation, changes in gene expression, the post-translational modification of proteins, and increases in SWS during periods of sleep rebound after sleep deprivation 163. Importantly, wakeful experience and learning have been shown to increase the length of time spent in NREM and REM sleep 62. Increased sleep duration due to learning, for example, could provide a longer window of time for oscillatory events including spindles and SPW-Rs to occur, thereby increasing the overall beneficial effects of sleep on memory consolidation. Alternatively, increased sleep duration could accompany learning-dependent alterations in the electrophysiological properties (e.g., power) of sleep-associated oscillatory activity. Indeed, learning-dependent increases in sleep need accompanied by increased SWA during NREM sleep and higher numbers of spindles in brain regions activated during learning have been demonstrated and correlated with levels of sleep-dependent performance enhancements 61,72,73. Thus, sleep need, at least under certain circumstances, appears to be regulated at local and global levels, warranting further investigation 153. In contrast, Walker et al. 168 has shown that doubling the quantity of initial training does not alter the amount of sleep-dependent learning in a finger tapping motor task. However, it has been shown that more difficult motor sequences benefit more from sleep than easy motor sequences 32,91. This could be because weakly encoded procedural memories experience a greater benefit from sleep than strongly encoded memories, simply because there is more room for improvement. If task performance in well-learned memories is near maximal, as far as accuracy and speed are concerned, then little benefit from sleep might be expected.

In associative learning paradigms (e.g., fear conditioning), task difficulty might predict the magnitude of post-learning changes in sleep architecture and oscillatory patterns. Indeed, Steenland et al. 143 recently examined the effects of trace fear conditioning where the associative strength between a conditioned stimulus (a tone) and the unconditioned stimulus (a footshock) was altered by changing the difficulty of the task. That is the task can be made more difficult to learn by lengthening the duration of trace time - the delay between termination of the CS and presentation of the US. Mice conditioning using a short, 15 sec trace resulted in significant enhancements in delta power during subsequent NREM sleep relative to baseline, whereas mice conditioned with a more difficult 30 sec trace showed no significant enhancements in delta power relative to baseline. Together, these data suggest learning and plasticity affects sleep need and the electrophysiological properties of subsequent sleep, which, in turn, can modulate sleep-dependent memory enhancements.

Circadian rhythms, in addition to homeostatic mechanisms, can influence memory processing and post-learning sleep 11 through the regulation of transcription and translation within various brain regions 53,154. For example, hippocampal gene expression and enzyme activity have been shown to vary over the course of the day 20,31,35. In fact, up to 10% of the mammalian transcriptome may be under the control of circadian rhythms 19,33,95,121 Relevant to the role of cAMP-PKA-CREB pathway in sleep-memory interactions, Eckel-Mahan et al. have recently shown that ERK, MAPK and CREB phosphorylation, in addition to cAMP levels, undergo circadian oscillations in the hippocampus. Interference with these oscillations with physiological and pharmacological agents impaired the maintenance of hippocampal-dependent LTM suggesting reactivation of the cAMP-CREB pathway is influenced in part by circadian rhythms 35.

Clock genes (including Clock, Bmal1, Period, Cryptochrome, and Timeless in Drosophila) genes are also intimately tied to circadian rhythms in mammals and Drosophila and are thought to modulate learning and memory but there role in sleep-memory interactions have been largely unexplored 36,65. Clock genes could provide a means of binding sleep and memory consolidation. For example, clock genes may play a role in the temporally restricted expression of the effects of learning on sleep (i.e., increased slow wave activity confined to the first few hours of sleep) or to explain why sleep can be delayed until later in the same day yet still benefit memory 39,88,150,168 Certainly, genetic models targeting clock genes will prove useful in determining their role in sleep-memory interactions.

IV. Molecular replay and sleep-dependent memory processing

The replay of hippocampal cellular activity, during ripple events for example, is thought to reflect cellular activity that occurred during prior bouts of wake 41,85,122,142,174 Therefore, it may be possible that cellular replay during sleep could trigger a similar replay of the molecular events that occurred during encoding and early consolidation 51. Although the notion of molecular replay is far from conclusive, many of the signaling pathways shown in Figure 2 function in synaptic plasticity 75, synaptic homeostasis 75 learning and memory 86,173,175 and sleep 19,63. Indeed, the cAMP-PKA-CREB pathway plays a role in the transduction of environmental information during memory formation and is modulated by sleep deprivation, circadian rhythms and neurotransmitter systems involved in sleep-wake regulation.56,63,64,83,164,176. Thus, the cAMP-PKA-CREB signaling pathway is well-suited to play an integrative role in sleep-memory interactions.

V. The use of genetic models to study sleep-memory interactions

The ability to manipulate gene expression in mice and other organisms is an important tool in understanding sleep 23. Regional and even cell type-specific expression of altered genetic material can assess the role of those genes within precise loci in the brain. While the temporal control of gene expression has improved 78, the required temporal resolution to study sleep-memory interactions in mice, for example, must be on the order of minutes, since most studies are conducted while test subjects are otherwise sleeping. Moreover, rapid regulation is required because mice return to sleep shortly after training. Without this level of temporal control, genetic modifications could produce non-specific effects on memory and sleep or alter sleep-wake regulation preventing a direct analysis of sleep-memory interactions. Approaches similar to those used in optogenetic systems, whereby specific cell types can be optically stimulated in vivo via expression of light-activated channel rhodopsins 16, could be engineered to precisely modulate oscillatory patterns that occur during sleep to provide a direct measure of their effects on memory.

VI. Conclusion

Mounting evidence demonstrates that sleep plays a beneficial role in memory consolidation. Multifunctional signaling pathways involved in memory, sleep and sleep-wake regulation may have evolved to integrate the effects of sleep with memory processing. However, in order to better understand the role of sleep in memory processing, we need to establish testable, falsifiable hypotheses using a combination of new genetic approaches and methods that regulate the electrophysiological properties of the brain during sleep. These approaches will provide more direct evidence of sleep-memory interactions that extend beyond the correlational confines of standard methodologies toward a deeper understanding of the molecular basis of sleep-memory interactions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from NIA (AG-18199), NIMH (MH-60244), NHLBI (HL-60287), the Whitehall Foundation, the John Merck Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation (T.A.); NSF(0706858) (P.H).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Abel T, Lattal KM. Molecular mechanisms of memory acquisition, consolidation and retrieval. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:180. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed T, Frey JU. Plasticity-specific phosphorylation of CaMKII, MAP-kinases and CREB during late-LTP in rat hippocampal slices in vitro. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:477. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarenga TA, Patti CL, Andersen ML, et al. Paradoxical sleep deprivation impairs acquisition, consolidation, and retrieval of a discriminative avoidance task in rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;90:624. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnsten AF. Catecholamine and second messenger influences on prefrontal cortical networks of “representational knowledge”: a rational bridge between genetics and the symptoms of mental illness. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(Suppl 1):i6. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aserinsky E, Kleitman N. Regularly occurring periods of eye motility, and concomitant phenomena, during sleep. Science. 1953;118:273. doi: 10.1126/science.118.3062.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aton SJ, Seibt J, Dumoulin M, et al. Mechanisms of sleep-dependent consolidation of cortical plasticity. Neuron. 2009;61:454. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Axmacher N, Mormann F, Fernandez G, et al. Memory formation by neuronal synchronization. Brain Res Rev. 2006;52:170. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barros DM, Izquierdo LA, Mello e Souza T, et al. Molecular signalling pathways in the cerebral cortex are required for retrieval of one-trial avoidance learning in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2000;114:183. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bekinschtein P, Cammarota M, Igaz LM, et al. Persistence of long-term memory storage requires a late protein synthesis- and BDNF- dependent phase in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2007;53:261. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borbely A, Achermann P. In: Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. Kryger M, Roth T, Dement W, editors. W. B. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2000. p. 377. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourtchouladze R, Abel T, Berman N, et al. Different training procedures recruit either one or two critical periods for contextual memory consolidation, each of which requires protein synthesis and PKA. Learn Mem. 1998;5:365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buzsaki G. Theta oscillations in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2002;33:325. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buzsaki G, Leung LW, Vanderwolf CH. Cellular bases of hippocampal EEG in the behaving rat. Brain Res. 1983;287:139. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(83)90037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cantero JL, Atienza M, Stickgold R, et al. Sleep-dependent theta oscillations in the human hippocampus and neocortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10897.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cardin JA, Carlen M, Meletis K, et al. Targeted optogenetic stimulation and recording of neurons in vivo using cell-type-specific expression of Channelrhodopsin-2. Nat Protoc. 5:247. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casadio A, Martin KC, Giustetto M, et al. A transient, neuron-wide form of CREB-mediated long-term facilitation can be stabilized at specific synapses by local protein synthesis. Cell. 1999;99:221. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81653-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chew SJ, Vicario DS, Nottebohm F. Quantal duration of auditory memories. Science. 1996;274:1909. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cirelli C, Gutierrez CM, Tononi G. Extensive and divergent effects of sleep and wakefulness on brain gene expression. Neuron. 2004;41:35. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00814-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cirelli C, Tononi G. Differential expression of plasticity-related genes in waking and sleep and their regulation by the noradrenergic system. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9187. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09187.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cirelli C, Tononi G. Is Sleep Essential? PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collingridge GL, Isaac JT, Wang YT. Receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:952. doi: 10.1038/nrn1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crocker A, Sehgal A. Genetic analysis of sleep. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1220. doi: 10.1101/gad.1913110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui Z, Wang H, Tan Y, et al. Inducible and reversible NR1 knockout reveals crucial role of the NMDA receptor in preserving remote memories in the brain. Neuron. 2004;41:781. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dash PK, Hebert AE, Runyan JD. A unified theory for systems and cellular memory consolidation. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;45:30. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Gennaro L, Ferrara M. Sleep spindles: an overview. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7:423. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dement W, Kleitman N. Cyclic variations in EEG during sleep and their relation to eye movements, body motility, and dreaming. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1957;9:673. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(57)90088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dement W, Kleitman N. The relation of eye movements during sleep to dream activity: an objective method for the study of dreaming. J Exp Psychol. 1957;53:339. doi: 10.1037/h0048189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diekelmann S, Born J. The memory function of sleep. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:114. doi: 10.1038/nrn2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diekelmann S, Born J. One memory, two ways to consolidate? Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1085. doi: 10.1038/nn0907-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dolci C, Montaruli A, Roveda E, et al. Circadian variations in expression of the trkB receptor in adult rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2003;994:67. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drosopoulos S, Windau E, Wagner U, et al. Sleep enforces the temporal order in memory. PLoS One. 2007;2:e376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duffield GE, Best JD, Meurers BH, et al. Circadian programs of transcriptional activation, signaling, and protein turnover revealed by microarray analysis of mammalian cells. Curr Biol. 2002;12:551. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00765-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dujardin K, Guerrien A, Leconte P. Sleep, brain activation and cognition. Physiol Behav. 1990;47:1271. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90382-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eckel-Mahan KL, Phan T, Han S, et al. Circadian oscillation of hippocampal MAPK activity and cAmp: implications for memory persistence. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1074. doi: 10.1038/nn.2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eckel-Mahan KL, Storm DR. Circadian rhythms and memory: not so simple as cogs and gears. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:584. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enslen H, Sun P, Brickey D, et al. Characterization of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV. Role in transcriptional regulation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eschenko O, Molle M, Born J, et al. Elevated sleep spindle density after learning or after retrieval in rats. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12914. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3175-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fischer S, Hallschmid M, Elsner AL, et al. Sleep forms memory for finger skills. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182178199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fischer S, Nitschke MF, Melchert UH, et al. Motor memory consolidation in sleep shapes more effective neuronal representations. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11248. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1743-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foster DJ, Wilson MA. Reverse replay of behavioural sequences in hippocampal place cells during the awake state. Nature. 2006;440:680. doi: 10.1038/nature04587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frank MG, Issa NP, Stryker MP. Sleep enhances plasticity in the developing visual cortex. Neuron. 2001;30:275. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frank MG, Jha SK, Coleman T. Blockade of postsynaptic activity in sleep inhibits developmental plasticity in visual cortex. Neuroreport. 2006;17:1459. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000233100.05408.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frankland PW, Bontempi B. The organization of recent and remote memories. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:119. doi: 10.1038/nrn1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Freeman FM, Rose SP, Scholey AB. Two time windows of anisomycin-induced amnesia for passive avoidance training in the day-old chick. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 1995;63:291. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1995.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frey U, Krug M, Reymann KG, et al. Anisomycin, an inhibitor of protein synthesis, blocks late phases of LTP phenomena in the hippocampal CA1 region in vitro. Brain Research. 1988;452:57. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frey U, Morris RG. Synaptic tagging and long-term potentiation. Nature. 1997;385:533. doi: 10.1038/385533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frey U, Morris RG. Weak before strong: dissociating synaptic tagging and plasticity-factor accounts of late-LTP. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:545. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gais S, Albouy G, Boly M, et al. Sleep transforms the cerebral trace of declarative memories. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705454104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gais S, Rasch B, Wagner U, et al. Visual-procedural memory consolidation during sleep blocked by glutamatergic receptor antagonists. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5513. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5374-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ganguly-Fitzgerald I, Donlea J, Shaw PJ. Waking experience affects sleep need in Drosophila. Science. 2006;313:1775. doi: 10.1126/science.1130408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gelinas JN, Banko JL, Peters MM, et al. Activation of exchange protein activated by cyclic-AMP enhances long-lasting synaptic potentiation in the hippocampus. Learn Mem. 2008;15:403. doi: 10.1101/lm.830008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gerstner JR, Lyons LC, Wright KP, Jr., et al. Cycling Behavior and Memory Formation. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:12824. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3353-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Girardeau G, Benchenane K, Wiener SI, et al. Selective suppression of hippocampal ripples impairs spatial memory. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1222. doi: 10.1038/nn.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gordon W. Similarities of recently acquired and reactivated memories in interference. Am. J. Psychol. 1977;90:231. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gottlieb DJ, O'Connor GT, Wilk JB. Genome-wide association of sleep and circadian phenotypes. BMC Med Genet. 2007;8(Suppl 1):S9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grecksch G, Matthies H. Two sensitive periods for the amnesic effect of anisomycin. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 1980;12:663. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(80)90145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gvilia I. Underlying brain mechanisms that regulate sleep-wakefulness cycles. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2010;93:1. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(10)93001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Habib D, Dringenberg HC. Low-frequency-induced synaptic potentiation: a paradigm shift in the field of memory-related plasticity mechanisms? Hippocampus. 2010;20:29. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hagewoud R, Havekes R, Novati A, et al. Sleep deprivation impairs spatial working memory and reduces hippocampal AMPA receptor phosphorylation. J Sleep Res. 2010;19:280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hanlon EC, Faraguna U, Vyazovskiy VV, et al. Effects of skilled training on sleep slow wave activity and cortical gene expression in the rat. Sleep. 2009;32:719. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.6.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hellman K, Abel T. Fear conditioning increases NREM sleep. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2007;121:310. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.2.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hellman K, Hernandez P, Park A, et al. Genetic evidence for a role for protein kinase A in the maintenance of sleep and thalamocortical oscillations. Sleep. 2010;33:19. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hendricks JC, Finn SM, Panckeri KA, et al. Rest in Drosophila is a sleep-like state. Neuron. 2000;25:129. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80877-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hendricks JC, Sehgal A, Pack AI. The need for a simple animal model to understand sleep. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;61:339. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hennevin E, Leconte P. [Study of the relations between paradoxical sleep and learning processes (author's transl)] Physiol Behav. 1977;18:307. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(77)90138-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hernandez PJ, Abel T. The role of protein synthesis in memory consolidation: progress amid decades of debate. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89:293. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hipolide DC, Tufik S, Raymond R, et al. Heterogeneous effects of rapid eye movement sleep deprivation on binding to alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptor subtypes in rat brain. Neuroscience. 1998;86:977. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hobson JA, Pace-Schott EF. The cognitive neuroscience of sleep: neuronal systems, consciousness and learning. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:679. doi: 10.1038/nrn915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoffman KL, Battaglia FP, Harris K, et al. The upshot of up states in the neocortex: from slow oscillations to memory formation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3501-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang T, McDonough CB, Abel T. Compartmentalized PKA signaling events are required for synaptic tagging and capture during hippocampal late-phase long-term potentiation. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:635. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huber R, Ghilardi MF, Massimini M, et al. Arm immobilization causes cortical plastic changes and locally decreases sleep slow wave activity. Nat Neurosci. 2006 doi: 10.1038/nn1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huber R, Ghilardi MF, Massimini M, et al. Local sleep and learning. Nature. 2004;430:78. doi: 10.1038/nature02663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hyman JM, Wyble BP, Goyal V, et al. Stimulation in hippocampal region CA1 in behaving rats yields long-term potentiation when delivered to the peak of theta and long-term depression when delivered to the trough. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11725. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-37-11725.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ibata K, Sun Q, Turrigiano GG. Rapid synaptic scaling induced by changes in postsynaptic firing. Neuron. 2008;57:819. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, et al. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 1 American Academy of Sleep Medicine; Westchester, Illinois: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Igaz LM, Vianna MR, Medina JH, et al. Two time periods of hippocampal mRNA synthesis are required for memory consolidation of fear-motivated learning. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:6781. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06781.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Isiegas C, McDonough, C, Huang, T, Fabian, S, Wu, L-J, Xu, H, Zhao, M-G, Kim, J-I, Lee, Y-S, Lee, H-R, Ko, H-G, Lee, N, Son, H, Zhuo, M, Kaang, B-K, Abel, T. A novel conditional genetic system reveals that increasing neuronal cAMP enhances memory and retrieval. Submitted. 2007 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2935-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Isomura Y, Sirota A, Ozen S, et al. Integration and segregation of activity in entorhinal-hippocampal subregions by neocortical slow oscillations. Neuron. 2006;52:871. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Izquierdo LA, Barros DM, Ardenghi PG, et al. Different hippocampal molecular requirements for short- and long-term retrieval of one-trial avoidance learning. Behav Brain Res. 2000;111:93. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Izquierdo LA, Viola H, Barros DM, et al. Novelty enhances retrieval: molecular mechanisms involved in rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1464. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ji D, Wilson MA. Coordinated memory replay in the visual cortex and hippocampus during sleep. Nature Neuroscience. 2007;10:100. doi: 10.1038/nn1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Joiner WJ, Crocker A, White BH, et al. Sleep in Drosophila is regulated by adult mushroom bodies. Nature. 2006;441:757. doi: 10.1038/nature04811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jouvet M, Michel F. [Electromyographic correlations of sleep in the chronic decorticate & mesencephalic cat.] C R Seances Soc Biol Fil. 1959;153:422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kali S, Dayan P. Off-line replay maintains declarative memories in a model of hippocampal-neocortical interactions. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:286. doi: 10.1038/nn1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kang H, Sun LD, Atkins CM, et al. An important role of neural activity-dependent CaMKIV signaling in the consolidation of long-term memory. Cell. 2001;106:771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00497-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kelley AE, Andrzejewski ME, Baldwin AE, et al. Glutamate-mediated plasticity in corticostriatal networks: role in adaptive motor learning. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;1003:159. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Korman M, Doyon J, Doljansky J, et al. Daytime sleep condenses the time course of motor memory consolidation. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1206. doi: 10.1038/nn1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kryger M, Roth T, Dement W. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. ed 4th Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kudrimoti HS, Barnes CA, McNaughton BL. Reactivation of hippocampal cell assemblies: effects of behavioral state, experience, and EEG dynamics. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:4090. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-04090.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kuriyama K, Stickgold R, Walker MP. Sleep-dependent learning and motor-skill complexity. Learn Mem. 2004;11:705. doi: 10.1101/lm.76304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee JL. Memory reconsolidation mediates the strengthening of memories by additional learning. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1264. doi: 10.1038/nn.2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee JL, Di Ciano P, Thomas KL, et al. Disrupting reconsolidation of drug memories reduces cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuron. 2005;47:795. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Llinas R, Ribary U. Coherent 40-Hz oscillation characterizes dream state in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lowrey PL, Takahashi JS. Mammalian circadian biology: elucidating genome-wide levels of temporal organization. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2004;5:407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.5.061903.175925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Luppi PH. Neurochemical aspects of sleep regulation with specific focus on slow-wave sleep. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(Suppl 1):4. doi: 10.3109/15622971003637611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lynch MA. Long-term potentiation and memory. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:87. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ma N, Abel T, Hernandez PJ. Exchange protein activated by cAMP enhances long-term memory formation independent of protein kinase A. Learn Mem. 2009;16:367. doi: 10.1101/lm.1231009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Malenka RC, Bear MF. LTP and LTD: an embarrassment of riches. Neuron. 2004;44:5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maret Sp, Dorsaz Sp, Gurcel L, et al. Homer1a is a core brain molecular correlate of sleep loss. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:20090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710131104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Marshall L, Helgadottir H, Molle M, et al. Boosting slow oscillations during sleep potentiates memory. Nature. 2006;444:610. doi: 10.1038/nature05278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Martin KC, Casadio A, Zhu H, et al. Synapse-specific, long-term facilitation of aplysia sensory to motor synapses: a function for local protein synthesis in memory storage. Cell. 1997;91:927. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80484-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Martin KC, Kosik KS. Synaptic tagging -- who's it? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:813. doi: 10.1038/nrn942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Matthews RP, Guthrie CR, Wailes LM, et al. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase types II and IV differentially regulate CREB-dependent gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6107. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mayford M, Bach ME, Huang YY, et al. Control of memory formation through regulated expression of a CaMKII transgene. Science. 1996;274:1678. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mednick S, Nakayama K, Stickgold R. Sleep-dependent learning: a nap is as good as a night. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:697. doi: 10.1038/nn1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Misanin JR, Miller RR, Lewis DJ. Retrograde amnesia produced by electroconvulsive shock after reactivation of a consolidated memory trace. Science. 1968;160:554. doi: 10.1126/science.160.3827.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Molle M, Yeshenko O, Marshall L, et al. Hippocampal sharp wave-ripples linked to slow oscillations in rat slow-wave sleep. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:62. doi: 10.1152/jn.00014.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Moncada D, Viola H. Induction of Long-Term Memory by Exposure to Novelty Requires Protein Synthesis: Evidence for a Behavioral Tagging. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:7476. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1083-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Murchison CF, Zhang XY, Zhang WP, et al. A distinct role for norepinephrine in memory retrieval. Cell. 2004;117:131. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nader K, Einarsson EO. Memory reconsolidation: an update. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1191:27. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nakashiba T, Buhl DL, McHugh TJ, et al. Hippocampal CA3 output is crucial for ripple-associated reactivation and consolidation of memory. Neuron. 2009;62:781. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nakazawa K, McHugh TJ, Wilson MA, et al. NMDA receptors, place cells and hippocampal spatial memory. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:361. doi: 10.1038/nrn1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nguyen PV, Abel T, Kandel ER. Requirement of a critical period of transcription for induction of a late phase of LTP. Science. 1994;265:1104. doi: 10.1126/science.8066450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nishida M, Walker MP. Daytime naps, motor memory consolidation and regionally specific sleep spindles. PLoS One. 2007;2:e341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.O'Keefe J, Nadel L. The hippocampus as a cognitive map. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Okada D, Ozawa F, Inokuchi K. Input-specific spine entry of soma-derived Vesl-1S protein conforms to synaptic tagging. Science. 2009;324:904. doi: 10.1126/science.1171498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Orban P, Rauchs G, Balteau E, et al. Sleep after spatial learning promotes covert reorganization of brain activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510198103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ortiz O, Delgado-Garcia JM, Espadas I, et al. Associative learning and CA3-CA1 synaptic plasticity are impaired in D1R null, Drd1a−/− mice and in hippocampal siRNA silenced Drd1a mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2655-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Palagini L, Rosenlicht N. Sleep, dreaming, and mental health: A review of historical and neurobiological perspectives. Sleep Med Rev. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Panda S, Antoch MP, Miller BH, et al. Coordinated transcription of key pathways in the mouse by the circadian clock. Cell. 2002;109:307. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00722-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Pavlides C, Winson J. Influences of hippocampal place cell firing in the awake state on the activity of these cells during subsequent sleep episodes. Journal of Neuroscience. 1989;9:2907. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-08-02907.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Peigneux P, Laureys S, Delbeuck X, et al. Sleeping brain, learning brain. The role of sleep for memory systems. Neuroreport. 2001;12:A111. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112210-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Peng S, Zhang Y, Zhang J, et al. ERK in learning and memory: A review of recent research. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:222. doi: 10.3390/ijms11010222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Pittenger C, Kandel ER. In search of general mechanisms for long-lasting plasticity: Aplysia and the hippocampus. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 2003;358:757. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Qin YL, McNaughton BL, Skaggs WE, et al. Memory reprocessing in corticocortical and hippocampocortical neuronal ensembles. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1997;352:1525. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Radulovic J, Tronson NC. Molecular specificity of multiple hippocampal processes governing fear extinction. Rev Neurosci. 2010;21:1. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2010.21.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Rasch B, Born J. Maintaining memories by reactivation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:698. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Rasch B, Buchel C, Gais S, et al. Odor cues during slow-wave sleep prompt declarative memory consolidation. Science. 2007;315:1426. doi: 10.1126/science.1138581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Rauchs G, Desgranges B, Foret J, et al. The relationships between memory systems and sleep stages. J Sleep Res. 2005;14:123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Raymond CR. LTP forms 1, 2 and 3: different mechanisms for the “long” in long-term potentiation. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:167. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Roberson ED, English JD, Adams JP, et al. The mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade couples PKA and PKC to cAMP response element binding protein phosphorylation in area CA1 of hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:4337. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04337.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Roberson R, Cameroni I, Toso L, et al. Alterations in phosphorylated cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element of binding protein activity: a pathway for fetal alcohol syndrome-related neurotoxicity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:193 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Rossato JI, Bevilaqua LRM, Izquierdo I, et al. Dopamine Controls Persistence of Long-Term Memory Storage. Science. 2009;325:1017. doi: 10.1126/science.1172545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Routtenberg A, Rekart JL. Post-translational protein modification as the substrate for long-lasting memory. Trends in Neurosciences. 2005;28:12. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Schabus M, Gruber G, Parapatics S, et al. Sleep spindles and their significance for declarative memory consolidation. Sleep. 2004;27:1479. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Schneider AM, Sherman W. Amnesia: a function of the temporal relation of footshock to electroconvulsive shock. Science. 1968;159:219. doi: 10.1126/science.159.3811.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Schulz S, Siemer H, Krug M, et al. Direct evidence for biphasic cAMP responsive element-binding protein phosphorylation during long-term potentiation in the rat dentate gyrus in vivo. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05683.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Shema R, Sacktor TC, Dudai Y. Rapid erasure of long-term memory associations in the cortex by an inhibitor of PKM zeta. Science. 2007;317:951. doi: 10.1126/science.1144334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Siapas AG, Wilson MA. Coordinated interactions between hippocampal ripples and cortical spindles during slow-wave sleep. Neuron. 1998;21:1123. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80629-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Sirota A, Csicsvari J, Buhl D, et al. Communication between neocortex and hippocampus during sleep in rodents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437938100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Skaggs WE, McNaughton BL. Replay of neuronal firing sequences in rat hippocampus during sleep following spatial experience. Science. 1996;271:1870. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5257.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Steenland H, Wu V, Fukushima H, et al. CaMKIV over-expression boosts cortical 4-7 Hz oscillations during learning and 1-4 Hz delta oscillations during sleep. Molecular Brain. 2010;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Steriade M. Grouping of brain rhythms in corticothalamic systems. Neuroscience. 2006;137:1087. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Steriade M, Contreras D, Amzica F, et al. Synchronization of fast (30-40 Hz) spontaneous oscillations in intrathalamic and thalamocortical networks. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2788. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02788.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Steriade M, Nunez A, Amzica F. Intracellular analysis of relations between the slow (< 1 Hz) neocortical oscillation and other sleep rhythms of the electroencephalogram. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3266. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03266.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Steriade M, Timofeev I. Neuronal plasticity in thalamocortical networks during sleep and waking oscillations. Neuron. 2003;37:563. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Stickgold R. Sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Nature. 2005;437:1272. doi: 10.1038/nature04286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Stickgold R, James L, Hobson JA. Visual discrimination learning requires sleep after training. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1237. doi: 10.1038/81756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Stickgold R, Whidbee D, Schirmer B, et al. Visual discrimination task improvement: A multi-step process occurring during sleep. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12:246. doi: 10.1162/089892900562075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Sutherland RJ, Sparks FT, Lehmann H. Hippocampus and retrograde amnesia in the rat model: A modest proposal for the situation of systems consolidation. Neuropsychologia. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Sutton MA, Schuman EM. Dendritic protein synthesis, synaptic plasticity, and memory. Cell. 2006;127:49. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Szymusiak R. Hypothalamic versus neocortical control of sleep. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16:530. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32833eec92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Takahashi JS, Hong HK, Ko CH, et al. The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: implications for physiology and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:764. doi: 10.1038/nrg2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Takashima A, Petersson KM, Rutters F, et al. Declarative memory consolidation in humans: a prospective functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507774103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Timo-Iaria C, Negrao N, Schmidek WR, et al. Phases and states of sleep in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1970;5:1057. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(70)90162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep function and synaptic homeostasis. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:49. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Tononi G, Massimini M, Riedner BA. Sleepy dialogues between cortex and hippocampus: who talks to whom? Neuron. 2006;52:748. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Trifilieff P, Herry C, Vanhoutte P, et al. Foreground contextual fear memory consolidation requires two independent phases of hippocampal ERK/CREB activation. Learn Mem. 2006;13:349. doi: 10.1101/lm.80206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Tronson NC, Taylor JR. Molecular mechanisms of memory reconsolidation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:262. doi: 10.1038/nrn2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Tse D, Langston RF, Kakeyama M, et al. Schemas and Memory Consolidation. Science. 2007;316:76. doi: 10.1126/science.1135935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Vanderwolf CH. Hippocampal electrical activity and voluntary movement in the rat. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1969;26:407. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(69)90092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Vassalli A, Dijk DJ. Sleep function: current questions and new approaches. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:1830. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Vecsey CG, Baillie GS, Jaganath D, et al. Sleep deprivation impairs cAMP signalling in the hippocampus. Nature. 2009;461:1122. doi: 10.1038/nature08488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Vecsey CG, Hawk JD, Lattal KM, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors enhance memory and synaptic plasticity via CREB:CBP-dependent transcriptional activation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:6128. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0296-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Vyazovskiy VV, Cirelli C, Pfister-Genskow M, et al. Molecular and electrophysiological evidence for net synaptic potentiation in wake and depression in sleep. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:200. doi: 10.1038/nn2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Walker MP, Brakefield T, Hobson JA, et al. Dissociable stages of human memory consolidation and reconsolidation. Nature. 2003;425:616. doi: 10.1038/nature01930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Walker MP, Brakefield T, Seidman J, et al. Sleep and the time course of motor skill learning. Learn Mem. 2003;10:275. doi: 10.1101/lm.58503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Walker MP, Stickgold R. Sleep-dependent learning and memory consolidation. Neuron. 2004;44:121. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Walker MP, Stickgold R. Sleep, memory, and plasticity. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;57:139. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Walker MP, Stickgold R, Alsop D, et al. Sleep-dependent motor memory plasticity in the human brain. Neuroscience. 2005;133:911. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Wang SH, Morris RG. Hippocampal-neocortical interactions in memory formation, consolidation, and reconsolidation. Annu Rev Psychol. 2010;61:49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Wei F, Qiu CS, Liauw J, et al. Calcium calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV is required for fear memory. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:573. doi: 10.1038/nn0602-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Wilson MA, McNaughton BL. Reactivation of hippocampal ensemble memories during sleep. Science. 1994;265:676. doi: 10.1126/science.8036517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Wu LJ, Zhang XH, Fukushima H, et al. Genetic enhancement of trace fear memory and cingulate potentiation in mice overexpressing Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:1923. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Wu MN, Ho K, Crocker A, et al. The effects of caffeine on sleep in Drosophila require PKA activity, but not the adenosine receptor. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11029. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1653-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Yao Y, Kelly MT, Sajikumar S, et al. PKM zeta maintains late long-term potentiation by N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor/GluR2-dependent trafficking of postsynaptic AMPA receptors. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0223-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]