Early diagnosis and prompt splenectomy prior to splenic rupture may be the best chance for surviving this rare, aggressive malignant neoplasm arising from splenic vascular endothelium.

Keywords: Hemangiosarcoma, Splenic cancer

Abstract

Primary splenic angiosarcoma is a rare, aggressive malignant neoplasm arising from splenic vascular endothelium. A 70-year-old woman presented with shortness of breath and chest discomfort secondary to a left-sided pleural effusion. A thoracentesis revealed a reactive effusion suspicious for malignancy. Splenic enlargement with heterogeneous enhancement was identified on CT of the abdomen. Laboratory findings at initial presentation revealed mild anemia (10.5g/dL) with normal platelets (300 × 109/L). Laparoscopic splenectomy was performed, and a primary splenic angiosarcoma was discovered. After 2 rounds of chemotherapy, a CT scan showed progressive disease with metastasis to the liver and lung. The patient's antineoplastic regimen was switched to Ifosfamide and Doxorubicin. She is currently alive with evidence of disease at 9 months but without further progression. Primary splenic angiosarcoma is almost universally fatal despite treatment. The best chance for survival is early diagnosis and prompt splenectomy prior to splenic rupture.

INTRODUCTION

Primary splenic angiosarcomas are rare, aggressive malignant neoplasms arising from splenic sinusoidal vascular endothelium. First described by Langhans in 1879,1 it is among the rarest types of neoplasm, with an estimated annual incidence of 0.14 to 0.25 cases per million persons.2,3 Splenectomy is thought to be the only intervention that may result in long-term, disease-free survival. Primary splenic angiosarcomas are associated with a very poor prognosis, because they have proven to be highly refractory to adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy. Almost all patients die within 12 months of diagnosis regardless of treatment.2–4 Very few reviews are available to date in the literature.2,3 A case report of this rare clinical entity and complete review of the current literature are provided.

CASE REPORT

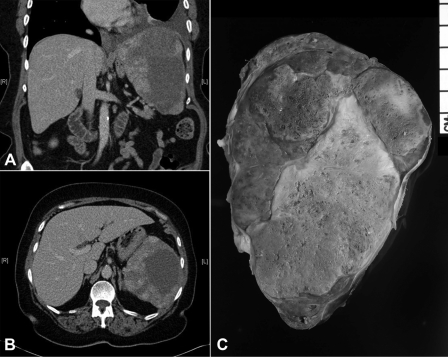

The patient is a 70-year-old woman who presented to her primary care physician with shortness of breath and chest discomfort secondary to a moderate left-sided pleural effusion. Her past medical history was significant for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and papillary thyroid cancer treated with surgery and postoperative radioiodine ablation 18 years earlier. A thoracentesis was performed with findings consistent with a reactive effusion and numerous mesothelial cells admixed with inflammatory cells. The suspicion of a neoplastic process remained high, and the patient had a recurrence of the pleural effusion. A computed tomography (CT) scan was done, demonstrating the previously known effusion and splenomegaly. Splenic enlargement with heterogeneous enhancement was identified (Figures 1A, 1B). The differential diagnosis was infarct, hematoma, or metastatic mass lesion. Laboratory findings at initial presentation revealed mild anemia (10.5g/dL) with normal platelets (300 × 109/L).

Figure 1.

(A) CT image coronal view of splenic mass; (B) CT image transverse view of splenic mass. (C) Gross specimen.

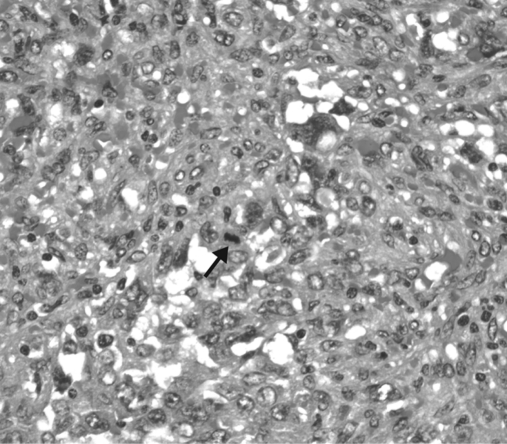

After surgical consultation, we performed a hand-assisted laparoscopic splenectomy. The patient was placed in the right lateral position at a 45-degree angle with the table. Access was gained just superior to the umbilicus, and 3 additional left subcostal ports were placed under direct vision. The splenic flexure of the colon was taken down. The inferior pole vessels of the spleen were dissected out and taken with a vascular loaded linear endoscopic stapler. The gastrosplenic ligament was then opened and short gastric vessels taken with the ultrasonic shears. The splenic hilum was then dissected out. Care was taken not to violate the splenic capsule or the pancreatic parenchyma. The hilum and superior pole vessels were then taken with a 60-mm vascular loaded stapler. An additional hilar splenule had been identified and taken en bloc with the specimen. The supraumbilical incision was then enlarged to 9cm, and the GelPort hand access device (Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA) placed. With the intraabdominal hand retracting the spleen, the remaining diaphragmatic and retroperitoneal attachments were taken down and the spleen bagged. The bagged spleen (Figure 1C) was then removed intact through the GelPort incision aided by stretching and retraction of the fascia and skin. Pneumoperitoneum was then reestablished and laparoscopic examination of the left upper quadrant and liver performed. Hemostasis was secured, no additional metastatic lesions were found, and the procedure terminated. The patient tolerated the procedure well and had an uneventful hospital course. On histological examination, the specimen was found to have marked pleomorphic and ovoid nuclei with eosinophilic globules throughout the cytoplasm (Figure 2). The mitotic activity varied from 0 to 3 mitotic figures per one high-power field (Figure 3). Approximately 5% to 10% of the neoplastic cells expressed proliferation marker Ki-67 (Figure 4). The neoplastic cells were all strongly positive for CD31 and CD34. The majority of them were also strongly positive for the vascular marker von Willebrand Factor, but they were negative for CD8. Final pathology revealed a primary splenic angiosarcoma metastatic to the hilar splenule. A left liver biopsy was performed at the time of surgery and was found to be free of disease.

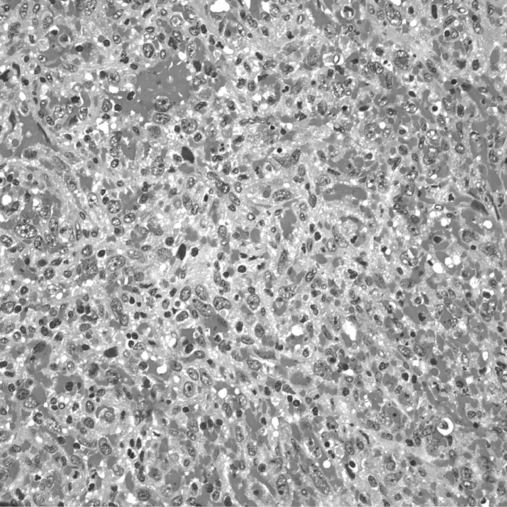

Figure 2.

Splenic parenchyma is partially replaced by a spindle cell neoplasm that forms abortive vascular lumina and contains numerous extravasated erythrocytes.

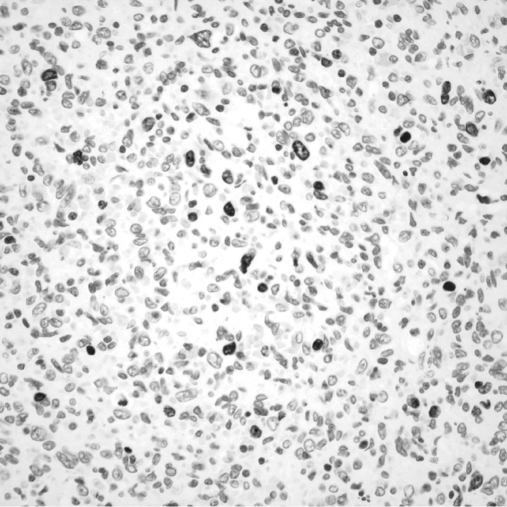

Figure 3.

Neoplastic cells expressing the Ki-67 proliferation marker.

Figure 4.

Mitotic figure (arrow).

The patient was started on an initial chemotherapy regimen of Gemcitabine HCl and Docetaxel. After 2 rounds of treatment, a CT scan showed progressive disease with metastasis to the liver and left lower lobe of the lung. The patient's chemotherapy regimen was switched to Ifosfamide and Doxorubicin, and she has not had further progression of disease after 4 rounds of this second regimen. She is currently alive but with evidence of disease at 8 months following her initial presentation.

DISCUSSION

Primary angiosarcoma of the spleen is a rare and aggressive malignant neoplasm arising from splenic vascular endothelium and mesenchymal-derived elongated endothelial cells lining the spleen's spongy network of sinusoids. In general, angiosarcomas are rapidly proliferating, highly infiltrating anaplastic cells that tend to recur locally, spread widely, and have an increased rate of lymph node and systemic metastases.2–8 Splenic angiosarcomas have also shown a slight predilection for women, but no sexual predilection has been found.3 They occur almost exclusively after 40 years of age.2–5 Only 9 cases have been reported in the pediatric literature to date.9

There are no specific clinical diagnostic guidelines for this rare entity, but upper abdominal pain is the predominant presenting symptom in more than 80% of cases. Constitutional symptoms common in malignancy, such as fever, fatigue, and weight loss, have also been observed but are the initial symptoms less than 10% of the time.2,3,6–8 Upon physical examination, splenomegaly is frequent, and a palpable left upper quadrant mass can often be found. Splenic rupture rates have been reported at 13% to 32%. Anemia is the most common laboratory abnormality in 75% to 81% of cases, although 10% to 40% of patients have thrombocytopenia; leukocytosis is often noted.2–4,6–9

The pathogenesis of splenic angiosarcomas is unknown. A few patients have been described with splenic angiosarcomas many years after receiving radiation therapy for other malignancies. However, no clear relationship with radiation exposure has been established to date.10 Some authors have hypothesized that primary splenic angiosarcomas may be the result of malignant transformation of other benign splenic tumors, such as hemangiomas, lymphangiomas, and hemangioendotheliomas.2,3,6,9,11 Thorium dioxide, vinyl chloride, and arsenic have been implicated in the formation of hepatic angiosarcomas, but no etiologic association between these substances and splenic angiosarcomas has been substantiated. Chemotherapy has also not been implicated as a potential cause of angiosarcomas of the spleen.2–4,6–8

Patients with splenic angiosarcoma often have spleens weighing >1000g.2 Macroscopically, there may be diffuse involvement of the spleen and replacement of the entire splenic parenchyma with tumor. Solitary masses are uncommon, and most tumors have usually undergone hemorrhage and necrosis. The histologic appearance of splenic angiosarcomas is quite heterogeneous. Immunohistochemical investigations have suggested that primary splenic angiosarcomas may arise from splenic sinus endothelial cells.3,12 Thus, these tumors show at least a focal vasoformative component, though it is usually the dominant pattern.3,9 The tumor consists of disorganized anastomosing vascular channels lined by large, atypical endothelial cells with significant irregular, hyperchromatic nuclei. Poorly differentiated areas have sarcomatous features, whereas well-differentiated regions appear very similar to the sinuses of the spleen. Mark et al13 found that histological appearance or grade is not related to outcome, because well-differentiated lesions can behave as aggressively as poorly differentiated ones. In a multivariate analysis of 55 cases of angiosarcoma, Naka et al14 determined that mitotic counts and tumor size were prognostic factors. Due to their variable histology, malignant vascular neoplasms of the spleen may be confused with benign vascular tumors or malignant nonvascular tumors.3,4

Metastases occur in 69% to 100% of cases of splenic angiosarcoma.2,3,10,15 Neuhauser et al3 reported the rates of metastases as 89% to the liver, 78% to the lungs, 56% to lymph nodes, and 44% to bone. Falk et al2 found rates of metastases as 41% to the liver, 22% to bone or its marrow, and 3% to lymph nodes. Metastases were not necessarily associated with higher mortality or accelerated death in their study.

The radiologic features of splenic angiosarcomas vary with imaging modality. Ultrasound, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) all display well evidence of splenomegaly. On ultrasound, a complex mass with heterogeneous echotexture is the most common finding. Areas of necrosis and hemorrhage are frequently noted as cystic areas within the mass.4 On CT scans, the most common finding is an ill-defined heterogeneously enhancing splenic mass with areas of necrosis. In the event of acute rupture, hemorrhage will appear hyperattenuated on unenhanced images. There is no particular pattern of calcification associated with splenic angiosarcoma, but areas of hypervascular metastases to the liver, lungs, bones, and lymphatic system are well demonstrated on CT.3–5 On MRI, T1- and T2-weighted pulse sequences show areas of increased and decreased signal intensity that are consistent with necrosis and the presence of hemorrhage. MRI with contrast enhancement shows heterogeneous enhancement within the tumor reflective of solid tumor with areas of necrosis.4,5 Regardless of imaging modality, radiologic diagnosis of splenic angiosarcoma remains highly challenging due to the great overlap with other vascular splenic tumors, such as hemangiomas, littoral cell angiomas, lymphangiomas, hemangiopericytomas, and epithelioid vascular tumors that may all mimic it. Additionally, other malignant tumors must be considered in the differential diagnosis, such as lymphoma, metastatic disease, and other rare sarcomas.5

Splenic angiosarcoma is usually treated with splenectomy, although it is rarely curative due to the aggressive and metastatic nature of the disease.2,3,10,11 In a study of 28 patients with primary splenic angiosarcoma done by Neuhauser et al,3 only 2 patients were alive at last follow-up, one with evidence of disease at 8 years who had received combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy and one without evidence of disease at 10 years who had been treated by splenectomy alone. Of the remaining 26 patients, one was lost to follow-up, and the other 25 died of disseminated disease. There was no statistically significant correlation between survival and nonsurgical treatment rendered (chemotherapy, radiation, or combination). The longest recorded duration of survival in a patient with primary splenic angiosarcoma is 16 years in a pediatric patient who was treated with splenectomy alone at 7 years of age.9 At this time, there is no convincing evidence to suggest a clinical benefit of chemotherapy in the treatment of splenic angiosarcoma.3,10 Splenectomy prior to rupture has been demonstrated to increase length of survival compared with splenectomy after rupture.2 Montemayor and Caggiano16 confirmed this finding and showed that mean survival times of splenectomy prior to rupture versus after rupture were 14.4 and 4.4 months, respectively.

CONCLUSION

Primary splenic angiosarcoma is a rare and aggressive malignancy found primarily in adults over 40 years of age and almost universally fatal despite treatment. Its pathogenesis remains unclear, and its clinical and radiologic diagnoses are challenging. The diagnosis should be suspected in any patient with splenomegaly and anemia of unknown etiology. Radiation and chemotherapy have historically been unsuccessful in improving outcome in this patient population. More evaluation of these options will be needed due to limited experience thus far. The best chance for survival is early diagnosis and prompt splenectomy prior to splenic rupture.

References

- 1. Langhans T. Pulsating cavernous neoplasm of the spleen with metastatic nodules to the liver. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat. 1879;75:273–291 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Falk S, Krishnan J, Meis JM. Primary angiosarcoma of the spleen. A clinicopathologic study of 40 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:959–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neuhauser TS, Derringer GA, Thompson LD, et al. Splenic angiosarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 28 cases. Mod Pathol. 2000;13(9):978–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abbott RM, Levy AD, Aguilera NS, Gorospe L, Thompson WM. From the archives of the AFIP: primary vascular neoplasms of the spleen: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2004;24:1137–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thompson WM, Levy AD, Aguilera NS, Gorospe L, Abbott RM. Angiosarcoma of the spleen: imaging characteristics in 12 patients. Radiology. 2005;235:106–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hai SA, Genato R, Gressel I, Khan P. Primary splenic angiosarcoma: case report and literature review. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92:143–146 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McGinley K, Googe P, Hanna W, Bell J. Primary angiosarcoma of the spleen: a case report and review of the literature. South Med J. 1995;88:873–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith VC, Eisenberg BL, McDonald EC. Primary splenic angiosarcoma. Case report and literature review. Cancer. 1985;55:1625–1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hsu JT, Ueng SH, Hwang TL, Chen HM, Jan YY, Chen MF. Primary angiosarcoma of the spleen in a child with long-term survival. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007;23:807–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sordillo EM, Sordillo PP, Hajdu SI. Primary hemangiosarcoma of the spleen: report of four cases. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1981;9:319–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arber DA, Strickler JG, Chen YY, Weiss LM. Splenic vascular tumors: a histologic, immunophenotypic, and virologic study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:827–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Takato H, Iwamoto H, Ikezu M, Kato N, Ikarashi T, Kaneko H. Splenic hemangiosarcoma with sinus endothelial differentiation. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1993;43:702–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mark RJ, Poen JC, Tran LM, Fu YS, Juillard GF. Angiosarcoma. A report of 67 patients and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1996;77:2400–2406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Naka N, Ohsawa M, Tomita Y, et al. Prognostic factors in angiosarcoma: a multivariate analysis of 55 cases. J Surg Oncol. 1996;61:170–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kren L, Kaur P, Goncharuk VN, Dolezel Z, Krenova Z. Primary angiosarcomas of the spleen in a child. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;40:411–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Montemayor P, Caggiano V. Primary hemangiosarcoma of the spleen associated with leukocytosis and abnormal spleen scan. Int Surg. 1980;65:369–373 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]