Abstract

Gene transfer could provide a novel therapeutic approach for cystic fibrosis (CF), and adeno-associated virus (AAV) is a promising vector. However, the packaging capacity of AAV limits inclusion of the full-length cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) cDNA together with other regulatory and structural elements. To overcome AAV size constraints, we recently developed a shortened CFTR missing the N-terminal portion of the R domain (residues 708–759, CFTRΔR) and found that it retained regulated anion channel activity in vitro. To test the hypothesis that CFTRΔR could correct in vivo defects, we generated CFTR−/− mice bearing a transgene with a fatty acid binding protein promoter driving expression of human CFTRΔR in the intestine (CFTR−/−;TgΔR). We found that intestinal crypts of CFTR−/−;TgΔR mice expressed CFTRΔR and the intestine appeared histologically similar to that of WT mice. Moreover, like full-length CFTR transgene, the CFTRΔR transgene produced CFTR Cl− currents and rescued the CFTR−/− intestinal phenotype. These results indicate that the N-terminal part of the CFTR R domain is dispensable for in vivo intestinal physiology. Thus, CFTRΔR may have utility for AAV-mediated gene transfer in CF.

Keywords: gene therapy, transgenic mice

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by mutations in the gene encoding the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (1, 2). The disease affects many organs, including the intestine, pancreas, lung, sweat gland duct, liver, gallbladder, and vas deferens. In these organs, CFTR is expressed in epithelia, where it forms a regulated anion channel, and loss of its function causes defective transepithelial electrolyte transport. Disease of the pulmonary airways is the current main cause of morbidity and mortality in humans.

Previous work demonstrated that expressing CFTR in CF cells could restore defective anion transport (3, 4). Those and additional observations suggested that transfer of the CFTR cDNA to CF epithelia might prevent and/or treat disease (5–7). Hence, several viral and nonviral vectors have been developed to deliver the CFTR cDNA to airway epithelia. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) is one of the vectors that have shown promise for CF gene transfer (6, 7). Advantages of AAV vectors are that transgene expression can be prolonged, they retain no protein-coding sequences, and the safety profile is encouraging. In addition, AAV vectors that target human airway epithelia from the apical surface have been developed (8–13). However, one limitation of AAV vectors is the relatively short packaging capacity. AAV has a genomic sequence of 4,700–4,900 bp, and although results vary, most data suggest that AAV vectors have a limited ability to incorporate long cDNA sequences (14–19). For CF gene transfer, it has not been feasible to incorporate the full-length CFTR cDNA (4,450 bp) together with a full promoter and other regulatory elements into an expression cassette.

In an attempt to overcome this limitation, we designed a short CFTR expression cassette to fit into the AAV viral vector (20). We reduced the CFTR cDNA size by deleting the coding sequence for 52 amino acids (residues 708–759) in the N-terminal portion of the R domain, generating a construct called CFTRΔR. We chose this portion of the R domain because it is poorly conserved across species, it is unstructured in solution, and, importantly, it can be deleted without apparently changing CFTR channel function (20, 21). Deleting residues 708–759 does, however, delete Ser-737, a known site for phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. When expressed with an adenovirus vector, CFTRΔR was functional in vitro in differentiated human airway epithelia and in vivo in murine nasal epithelium (21). In unpublished studies, we had not been able to incorporate a full-length CFTR cDNA plus regulatory elements into AAV vectors. However, when we combined the CFTRΔR coding sequence together with a shortened CMV promoter in an AAV5 vector, it was nearly as effective as a full-length CMV promoter and a full-length CFTR coding sequence at expressing functional CFTR in differentiated human airway epithelia in vitro (20). In addition, when the CFTRΔR construct was packaged in an evolved chimeric AAV2/5 vector, it transduced differentiated CF airway epithelia to levels similar to those generated by a recombinant adenovirus containing a full-length CFTR cDNA (8). Other reported approaches to generating a shortened CFTR involve deleting the N terminus plus some transmembrane domains (22) and deleting the R domain and/or C terminus (23).

These studies suggested that a CFTR construct lacking the N-terminal portion of the R domain might be useful for gene transfer applications in CF. However, a remaining important question is, can CFTRΔR correct a clinical phenotype? To answer this question, we turned to CFTR−/− mice. Although CFTR−/− mice do not develop lung disease typical of CF, they do manifest intestinal disease (24, 25). CFTR−/− mice lack CFTR-mediated Cl− current in the intestine and show intestinal inflammation, mucus accumulation, and distention that cause lethality around the time of weaning. We were motivated by the work of Zhou et al. (26), who used an intestinal fatty acid-binding protein (iFABP) promoter (27) to drive expression of full-length human CFTR (hCFTR) cDNA in the intestine of CFTR−/− mice. The iFABP > hCFTR transgene restored intestinal Cl− current stimulated by cAMP and, importantly, rescued the lethal intestinal phenotype of CFTR−/− mice. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that intestinal expression of hCFTRΔR would correct the intestinal phenotype in CFTR−/− mice. To do this, we studied CFTR−/− mice carrying an iFABP promoter driving expression of the hCFTRΔR cDNA (hereafter called CFTR−/−;TgΔR mice).

Results

CFTR−/− Mice Carrying the hCFTRΔR Transgene Have a Growth Defect.

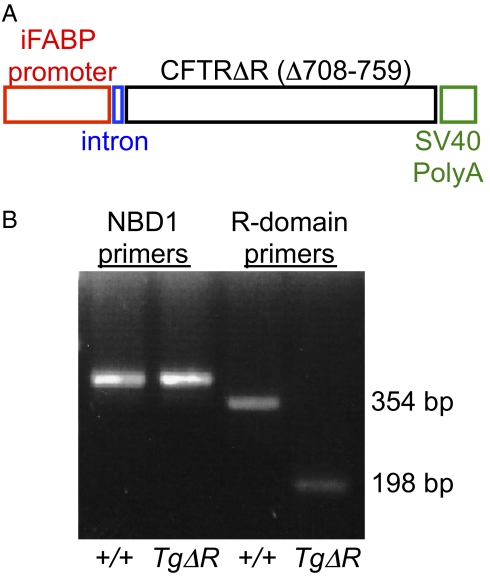

We produced transgenic mice that carried an iFABP > hCFTRΔR construct (Fig. 1A), crossed those mice to CFTR+/− mice (24), and, through mating, generated CFTR−/−;TgΔR mice. RT-PCR from CFTR−/−;TgΔR intestinal mRNA using primers flanking the R domain deletion revealed products corresponding to the expected size of the deleted construct, and sequencing verified the absence of nucleotides encoding residues 708–759 of the R domain (Fig. 1B). Amplification of sequences encoding NBD1 was identical in both CFTR+/+ and CFTR−/−;TgΔR mice. CFTR−/− mice carrying a transgene from three independent founder lines appeared identical. Offspring were born with expected Mendelian ratios suggesting no embryonic lethality (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Composition and verification of the transgenic vector. (A) Map of the transgene vector with the rat intestinal fatty acid binding promoter (nt −1788 to +28) and the CFTRΔR cDNA sequence (nt 1–4440 missing nt 2122–2277) followed by an SV40 late polyA signal sequence. (B) cDNA from reverse transcribed RNA isolated from intestine of WT and transgenic mice was used to amplify sequences encoding NBD1 (lanes 1 and 2) and the region of the R domain flanking the deleted sequence (lanes 3 and 4).

Table 1.

Distribution of genotypes when CFTR+/− mice were crossed with CFTR+/−;TgΔR mice

| Genotype | Observed | Expected |

| CFTR+/+;TgΔR | 44 | 45 |

| CFTR+/−;TgΔR | 92 | 90 |

| CFTR−/−;TgΔR | 38 | 45 |

| CFTR+/+ | 38 | 45 |

| CFTR+/− | 108 | 90 |

| CFTR−/− | 41 | 45 |

The observed distribution did not differ from the expected distribution (P = 0.3286, χ2 test).

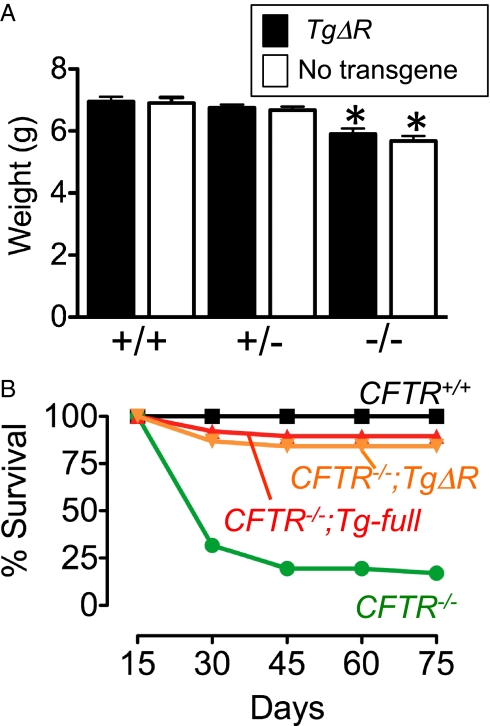

Ten days after birth, CFTR−/− mice weighed less than their WT or transgenic littermates (Fig. 2A), similar to observations in CFTR−/− mice (24, 28), CFTR−/− pigs (29), and humans with CF (30, 31). These results suggest that the growth defect may not be due solely to reduced or absent CFTR in intestinal epithelium, a result consistent with findings in CF pigs and humans with CF (29).

Fig. 2.

Weight and viability of CFTR−/−;TgΔR mice. (A) Mice were weighed 10 d after birth. Weights of male and female mice were not significantly different and are combined. *P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni test). (B) Viability of CFTR−/−;TgΔR mice is the same as that of CFTR−/−;Tg-full mice and approaches that of CFTR+/+ mice. Viability rates were similar in all three CFTR−/−;TgΔR founder lines and are combined. CFTR+/+ (n = 38), CFTR−/− (n = 41), CFTR−/−;TgΔR (n = 38), and CFTR−/−;Tg-full (n = 38).

CFTRΔR Rescues the Intestinal Phenotype in CFTR−/− Mice.

Wild-type mice lived the entire 75 d of the study (Fig. 2B). When maintained under these same conditions, most CFTR−/− mice show mortality at weaning or shortly after, consistent with earlier studies (24). As previously reported (26), transgenic expression of full-length CFTR driven by the iFABP promoter rescued the intestinal phenotype of CFTR−/− mice (these animals are hereafter called CFTR−/−;Tg-full mice) (Fig. 2B). We obtained similar rescue with mice transgenic for CFTRΔR.

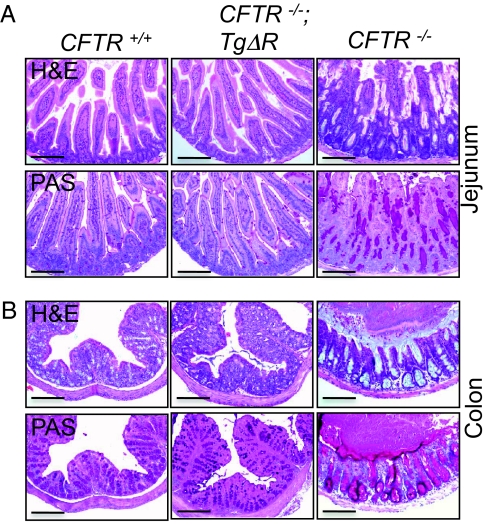

The small intestine and colon of CFTR−/− mice have excessive mucus production, dilated crypts, and obstruction of the intestinal lumen (24). To learn whether CFTRΔR can rescue the histopathological abnormalities, we examined intestines of CFTR−/−;TgΔR mice and compared them to CFTR−/− and CFTR+/+ mice (Fig. 3). CFTRΔR restored the morphology of both small and large intestines, although detailed morphometry would be required to determine whether the numbers of goblet cells were altered. CFTRΔR also reduced the excessive mucus observed in the crypts of CFTR−/− animals, as shown by the decreased staining of neutral mucins by PAS.

Fig. 3.

Expression of CFTRΔR in the intestine corrects the intestinal morphology of the CFTR−/− mouse. (A and B) H&E and PAS staining of jejunum (A) and colon (B). CFTR+/+ (Left), CFTR−/−;TgΔR (Center), and CFTR−/− (Right). (Scale bar, 160 μm.)

CFTRΔR Is Expressed in the Intestine of CFTR−/−;TgΔR Mice.

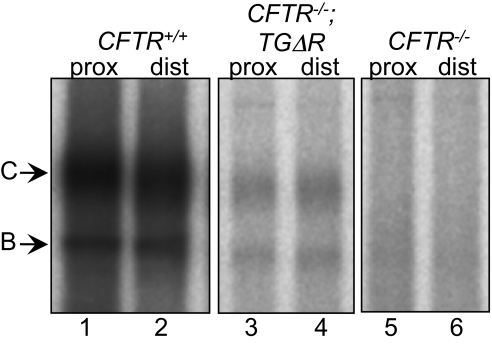

To assess the presence of CFTR in intestine, we immunoprecipitated and in vitro phosphorylated the protein and examined it after electrophoresis. In our hands, this procedure is more sensitive than Western blotting for detecting small amounts of CFTR. In both CFTR+/+ and CFTR−/−;TgΔR mice, we detected the mature fully glycosylated “band C” form of the protein and the immature core glycosylated “band B” form in both proximal and distal small intestine (Fig. 4). As expected, both bands migrated slightly faster in intestine from CFTR−/−;TgΔR than from WT mice. Although the intensity of CFTRΔR labeling was less than that of CFTR, CFTRΔR lacks Ser737, and therefore relative intensities may not indicate relative amounts of protein. We detected no CFTR in CFTR−/− mice.

Fig. 4.

Autoradiograph of CFTRΔR in the small intestine. CFTR from proximal and distal intestine is shown after immunoprecipitation, in vitro phosphorylation, and electrophoresis on SDS/PAGE. CFTR from the CFTR−/−;TgΔR intestine (lanes 3 and 4) migrates faster than that from CFTR+/+ intestine (lanes 1 and 2), consistent with deletion of residues 708–759. CFTR was not detected in CFTR−/− mouse intestine (lanes 5 and 6).

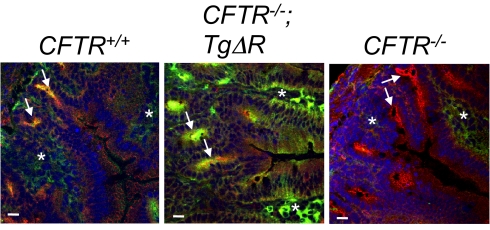

Consistent with previous reports (32–34), CFTR localized primarily in the crypts and not the villi of CFTR+/+ mouse intestine (Fig. 5). CFTR−/− intestine lacked detectable immunostaining. In CFTR−/−;TgΔR intestine, we detected CFTR primarily in the crypts, but also occasionally in the lower portion of villi. The intensity of immunostaining and background staining varied throughout the sections and was not a reliable indicator of relative amount of protein. The localization pattern is consistent with the expression pattern of iFABP, which is primarily expressed in the neck of the crypt and extends up into the villus (27). It is also consistent with a previous report for full-length CFTR in CFTR−/−;Tg-full mice (26).

Fig. 5.

Immunocytochemical localization of CFTR in mouse small intestine. CFTR was detected in crypts of CFTR+/+ and CFTR−/−;TgΔR mice, but not CFTR−/− mice. CFTR is green, the tight junction protein ZO-1 is red, and nuclei (stained with DAPI) are blue. Crypts are indicated by arrows. Asterisks (*) indicate nonspecific green staining that occurred to a variable extent in the interstitium of villi, including in CFTR−/− intestine. Staining of ZO-1 was variable and less prominent in the CFTR−/−;TgΔR image.

CFTRΔR Generates Cl− Secretion in the Intestine of CFTR−/−;TgΔR Mice.

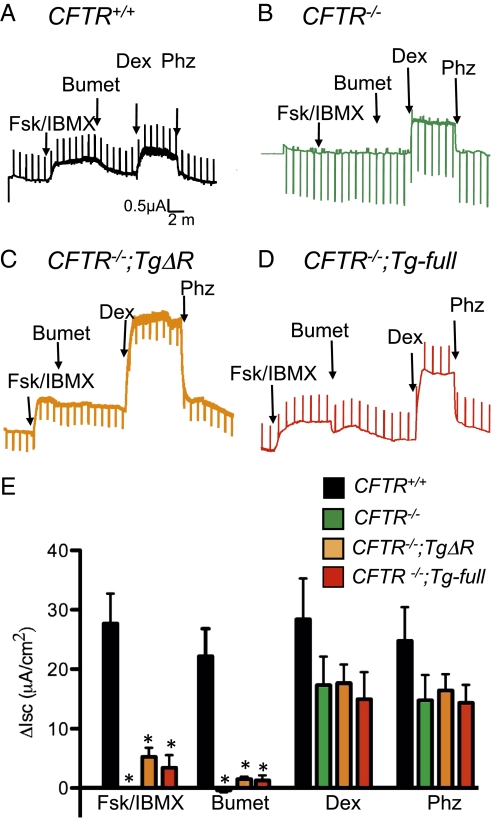

To learn whether intestinal CFTRΔR was functional, we excised pieces of intestine and assayed transepithelial currents in Ussing chambers. In WT intestine, adding forskolin and 1-methyl-3-isobutylxanthine (IBMX) to elevate cellular levels of cAMP increased short-circuit current (Isc) (Fig. 6A). Adding bumetanide, which inhibits the basolateral Na-K-2Cl cotransporter, reduced Isc. These changes are characteristic of transepithelial Cl− secretion mediated by CFTR. Consistent with that conclusion those responses were absent in CFTR−/− intestine (Fig. 6B). CFTR−/−;TgΔR intestine exhibited a forskolin and IBMX-stimulated current that was quantitatively similar to that in CFTR−/−;Tg-full mice (Fig. 6 C–E). Bumetanide inhibited Isc in both CFTR−/−;TgΔR and CFTR−/−;Tg-full intestine, but the extent of inhibition was much less than that in CFTR+/+ mice. The reason for reduced bumetanide-dependent inhibition is not known, but it has been reported previously in CFTR−/−;Tg-full mice (26). To test whether transepithelial transport was intact in excised epithelia, we added mucosal dextrose, which generates an Isc by providing substrate for the Na+-glucose cotransporter, and we then inhibited it with phlorizin (35) (Fig. 6). All genotypes generated similar currents.

Fig. 6.

Expression of CFTRΔR in the ileum partially restores cAMP-stimulated Isc. Representative Isc tracings from excised ileum of CFTR+/+ (A), CFTR−/− (B), CFTR−/−;TgΔR (C), and CFTR−/−;Tg-full (D) mice. Agents added were apical 100 μM forskolin and 10 μM IBMX (Fsk/IBMX), basolateral 100 μM bumetanide (Bumet), apical 5 mM dextrose (Dex), and 200 μM phlorizin (Phz). (E) Changes in Isc induced by indicated interventions. CFTR+/+ (n = 6), CFTR−/− (n = 8), CFTR−/−;TgΔR (n = 6), and CFTR−/−;Tg-full (n = 3). *P < 0.05 compared with CFTR+/+.

Discussion

AAV vectors have significant promise for gene transfer to CF airway epithelia. However, all AAV serotypes sequenced to date have genomes smaller than ∼5 kb. An earlier comprehensive study found that both packaging and expression of cDNAs in an AAV vector were optimal when the incorporated expression cassette was less than ∼4.8 kb (15). Since then, multiple attempts have been made to design expression cassettes that fit within this limit, primarily by limiting the size of the transgene (36, 37) or infecting with two vectors, each expressing half of the transgene (11, 38). Two studies reported that AAV vectors could package and express transgenes that substantially exceeded this limit, although at reduced efficiency (14, 17). However, more recent studies have demonstrated very inefficient packaging when the expression cassette exceeded a length of ∼5 kb (16, 19, 38). When attempts were made to incorporate large transgenes into AAV vectors, the transgenes tended to fragment and rearrange. Thus, most studies suggest that AAV vectors do not efficiently package transgenes greater than the length of the endogenous genome.

In this study, we used an expression cassette that included an hCFTR cDNA sequence missing 156 bp from the N-terminal part of the R domain. This expression cassette fits within the proposed 5-kb limit and, together with a shortened CMV promoter, generates a functional AAV vector (15, 20). Our previous studies indicated that CFTR lacking residues 708–759 functioned similarly to WT CFTR in macropatches and when expressed in differentiated human airway epithelia (20, 21). Our data now show that CFTRΔR can also rescue the CF phenotype in an animal model in vivo. With the iFABP promoter driving expression in CFTR−/− mouse intestine, hCFTRΔR generated the same level of intestinal Cl− transport as full-length hCFTR. CFTRΔR also corrected the increased mucus production, crypt dilation, and luminal obstruction of the CFTR−/− intestine, similar to what has been reported for full-length hCFTR (26). Importantly, like full-length CFTR, CFTRΔR substantially rescued the lethality that occurs at birth and around the time of weaning.

Because human CFTRΔR lacks the N-terminal portion of the R domain (residues 708–759), we conclude that those residues are not absolutely required for in vitro or in vivo function in the mouse. Earlier studies indicated that the R domain has both stimulatory and inhibitory functions in controlling channel activity, and that it is relatively unstructured (39, 40). Moreover, sequences in the R domain are not well conserved across different species. These observations raise interesting questions about the function of this portion of the R domain.

Our data indicate that CFTRΔR rescues a physiological abnormality and a clinical phenotype in the intestine of CFTR−/− mice. Thus, a shortened CFTR missing the N-terminal portion of the R domain may prove useful in the development of AAV-mediated gene transfer for CF.

Materials and Methods

Production of Transgenic Mice.

We designed the CFTRΔR transgene based on the pCI vector (Promega). We substituted the CMV promoter from pCI with the nucleotide sequence −1178 to +28 of the rat intestinal fatty acid binding protein (FABP) promoter (a gift from Jeffrey Gordon, Washington University, St. Louis, MO). We first mutated the vector to include two unique restriction sites (Nsi1 and Age1) that flanked the promoter and polyA sequence to facilitate excision for injection into one-cell pronuclear stage mouse embryos. The CFTRΔR coding sequence was amplified from pAd-173-IVS-CFTRΔR-SPA plasmid using Nhe1 and Kpn1 (20) and inserted into the multiple cloning site of the redesigned pCI-FABP vector (Fig. 1A) downstream of the chimeric intron (first intron of human β-globin gene and intron between leader and body of IgG heavy chain variable region) of the pCI vector. The redesigned plasmid was resequenced before use.

We excised the promoter through the CFTRΔR coding sequence and polyA sequence using Nsi1 and Age1 and injected the excised fragment into pronuclear stage embryo cells from B6SJL F2 mice. This procedure produced 13 founder lines expressing the CFTRΔR transgene (CFTR+/+;TgΔR). We crossed three of these founder mice with CFTR+/− mice (24) to generate CFTR+/− mice that were transgenic CFTRΔR (CFTR+/−;TgΔR). We bred those mice to generate CFTR−/−;TgΔR mice. Mice were genotyped using probes for mouse cftr, the neo gene, and the CFTRΔR transgene using a commercial vendor (Transnetyx). We also studied CFTR−/− mice that express a full-length CFTR transgene under control of the iFABP promoter (CFTR−/−;Tg-full) (26) (Jackson Labs) as controls. These mice were genotyped for mouse cftr, the neo gene, and full-length hCFTR. We used both male and female mice. Viability was measured for up to 75 d in CFTR−/−;Tg-ΔR mice derived from three different founder lines. Mice were maintained in the University of Iowa Animal Care Facility with free access to water and regular mouse chow. All studies were approved by and used procedures established by the University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee.

Verification of CFTRΔR Expression.

RNA expression.

Portions of small intestine were excised into RNAlater and stored frozen. RNA was isolated from the intestine (RNeasy-Lipid Tissue minikit, Qiagen). First-strand cDNA was synthesized with random hexamers (SuperScript III, Invitrogen). The DNA was amplified with primers flanking the CFTR coding sequence that includes the deleted residues. The amplified bands were sequenced to verify the accuracy of the expressed transgene. Regions of NBD1 were also amplified from both CFTR+/+ and CFTR−/−;TgΔR.

Protein expression.

CFTR was isolated from small intestines (proximal and distal) of weanling CFTR+/+, CFTR−/−, and CFTR−/−;TgΔR. Intestines were everted, placed in 0.14 M NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.4 buffer and vigorously shaken on a VX-2500 multitube Vortexer (VWR) at 1,800 rpm for 30 min. at 4 °C (41). The cells were pelleted at 4,000 rpm for 5 min. and stored at −80 °C in the following (in mM): 12 Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 300 mannitol, 10 KCl, 0.5 EDTA, and 0.1 PMSF, and a mixture of proteinase inhibitors (7 μg/mL benzamidine-HCl, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, 2 μg/mL aprotinin, and 2 μg/mL leupeptin). Protein concentrations were measured with the DC-BioRad Protein Assay. Equivalent concentrations of cells were vesiculated sequentially with 18-, 22-, and 25-gauge needles, pelleted at 70,000 × g, and solubilized in 1% Nonidet P-40 in the following (in mM): 50 Tris, 150 NaCl, 0.1 PMSF, and the mixture of proteinase inhibitors as described above (42). CFTR was immunoprecipitated from the supernatant of soluble proteins with anti-CFTR antibodies M3A7 and MM13-14 (Upstate Biotechnology) and in vitro phosphorylated with 32P-ATP and the catalytic subunit of PKA (Promega) (42). Washed precipitates were electrophoresed on 6% SDS/PAGE. Gels were stained, destained, dried, and exposed to phosphoscreens (Fuji) before imaging on a Fuji FLA7000 imager (General Electric).

Morphology.

Pieces of intestine from weanling mice were prosected and placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for fixation and were routinely processed and embedded. Sections (4 μm) were stained with H&E and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) for histopathological examination (43).

Immunocytochemistry.

Pieces of intestine from weanling mice were removed and placed in 30% sucrose and frozen immediately in OCT in liquid nitrogen. Tissue specimens were kept at −80 °C before sectioning at 7 μM. Sections were fixed at −20 °C in methanol, permeabilized briefly in 0.2% TX-100 in PBS and incubated with mouse anti-CFTR antibodies (0.01 μg/μL MM13-4) from Millipore, 0.007 μg/μL M3A7 from Millipore, and 0.002 μg/μL, 24-1 from R&D Systems, and rabbit anti–ZO-1 antibody (Zymed), followed by Alexa goat-antimouse A488 and goat-antirabbit 568 (Molecular Probes). To minimize reactivity with endogenous mouse proteins, we used the M.O.M. kit (Vector Labs). Intestines were imaged on an Olympus Fluoview FV1000 confocal microscope. Z-series were collected using the same settings for tissues from each genotype. Figures were adjusted postcollection identically for each genotype using Fluoview version 1.6 software.

Intestinal Electrophysiology.

Freshly excised ileum from weanling mice was everted and placed into holders with 3-mm apertures. Currents were measured in Ussing chambers (Jim's Instruments) with voltage clamps from Carver College of Medicine Bioengineering Services. Studies were done at 37 °C with symmetrical solutions containing (in mM): 118 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 2.4 KHPO4, 0.6 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgCl2, and 1.2 CaCl, pH 7.4, bubbled with 5% CO2/95% air (44). Epithelia were treated sequentially with 100 μM forskolin and 10 μM IBMX, 100 μM bumetanide, 5 mM dextrose, and 200 μM phlorizin. For some studies, we compared these mice with CFTR−/− mice and with the previously generated CFTR−/−;Tg-full mice (26).

Acknowledgments

We thank Norma Sinclair, Patricia Yarolem, and Joanne Schwarting for their technical expertise in generating transgenic mice. This work was supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Grant HL51670. We thank the University of Iowa In Vitro Models and Cell Culture Core (supported in part by NHLBI Grants HL51670 and HL091842, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Grant R458, the University of Iowa DNA Facility, the University of Iowa Animal Care Facility, and the University of Iowa Transgenic Animal Facility (supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and from the Roy J and Lucille A Carver College of Medicine). P.H.K. is a Research Specialist and M.J.W. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Welsh MJ, Ramsey BW, Accurso F, Cutting GR. Cystic fibrosis. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, Childs B, Vogelstein B, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease. 8 Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 5121–5189. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riordan JR, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: Cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989;245:1066–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drumm ML, et al. Correction of the cystic fibrosis defect in vitro by retrovirus-mediated gene transfer. Cell. 1990;62:1227–1233. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90398-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rich DP, et al. Expression of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator corrects defective chloride channel regulation in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Nature. 1990;347:358–363. doi: 10.1038/347358a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies JC, Alton EW. Gene therapy for cystic fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:408–414. doi: 10.1513/pats.201004-029AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flotte TR, et al. Viral vector-mediated and cell-based therapies for treatment of cystic fibrosis. Mol Ther. 2007;15:229–241. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson JM. Adeno-associated virus and lentivirus pseudotypes for lung-directed gene therapy. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1:309–314. doi: 10.1513/pats.200409-041MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Excoffon KJ, et al. Directed evolution of adeno-associated virus to an infectious respiratory virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3865–3870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813365106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halbert CL, Allen JM, Miller AD. Adeno-associated virus type 6 (AAV6) vectors mediate efficient transduction of airway epithelial cells in mouse lungs compared to that of AAV2 vectors. J Virol. 2001;75:6615–6624. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6615-6624.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sirninger J, et al. Functional characterization of a recombinant adeno-associated virus 5-pseudotyped cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator vector. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:832–841. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song Y, et al. Functional cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator expression in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells by AAV6.2-mediated segmental trans-splicing. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:267–281. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White AF, Mazur M, Sorscher EJ, Zinn KR, Ponnazhagan S. Genetic modification of adeno-associated viral vector type 2 capsid enhances gene transfer efficiency in polarized human airway epithelial cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:1407–1414. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zabner J, et al. Adeno-associated virus type 5 (AAV5) but not AAV2 binds to the apical surfaces of airway epithelia and facilitates gene transfer. J Virol. 2000;74:3852–3858. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3852-3858.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allocca M, et al. Serotype-dependent packaging of large genes in adeno-associated viral vectors results in effective gene delivery in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1955–1964. doi: 10.1172/JCI34316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong JY, Fan PD, Frizzell RA. Quantitative analysis of the packaging capacity of recombinant adeno-associated virus. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:2101–2112. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.17-2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong B, Nakai H, Xiao W. Characterization of genome integrity for oversized recombinant AAV vector. Mol Ther. 2010;18:87–92. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grieger JC, Samulski RJ. Packaging capacity of adeno-associated virus serotypes: Impact of larger genomes on infectivity and postentry steps. J Virol. 2005;79:9933–9944. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9933-9944.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai Y, Yue Y, Duan D. Evidence for the failure of adeno-associated virus serotype 5 to package a viral genome > or = 8.2 kb. Mol Ther. 2010;18:75–79. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Z, Yang H, Colosi P. Effect of genome size on AAV vector packaging. Mol Ther. 2010;18:80–86. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostedgaard LS, et al. A shortened adeno-associated virus expression cassette for CFTR gene transfer to cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2952–2957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409845102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ostedgaard LS, et al. CFTR with a partially deleted R domain corrects the cystic fibrosis chloride transport defect in human airway epithelia in vitro and in mouse nasal mucosa in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3093–3098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261714599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flotte TR, et al. Expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator from a novel adeno-associated virus promoter. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3781–3790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, et al. Efficient expression of CFTR function with adeno-associated virus vectors that carry shortened CFTR genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snouwaert JN, et al. An animal model for cystic fibrosis made by gene targeting. Science. 1992;257:1083–1088. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grubb BR, Boucher RC. Pathophysiology of gene-targeted mouse models for cystic fibrosis. Physiol Rev. 1999;79(1, Suppl):S193–S214. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou L, et al. Correction of lethal intestinal defect in a mouse model of cystic fibrosis by human CFTR. Science. 1994;266:1705–1708. doi: 10.1126/science.7527588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sweetser DA, Hauft SM, Hoppe PC, Birkenmeier EH, Gordon JI. Transgenic mice containing intestinal fatty acid-binding protein-human growth hormone fusion genes exhibit correct regional and cell-specific expression of the reporter gene in their small intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9611–9615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberg LA, Schluchter MD, Parlow AF, Drumm ML. Mouse as a model of growth retardation in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Res. 2006;59:191–195. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000196720.25938.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogan MP, et al. Pigs and humans with cystic fibrosis have reduced insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) levels at birth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20571–20575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015281107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Festini F, et al. Gestational and neonatal characteristics of children with cystic fibrosis: A cohort study. J Pediatr. 2005;147:316–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haeusler G, Frisch H, Waldhör T, Götz M. Perspectives of longitudinal growth in cystic fibrosis from birth to adult age. Eur J Pediatr. 1994;153:158–163. doi: 10.1007/BF01958975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ameen N, Alexis J, Salas P. Cellular localization of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in mouse intestinal tract. Histochem Cell Biol. 2000;114:69–75. doi: 10.1007/s004180000164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crawford I, et al. Immunocytochemical localization of the cystic fibrosis gene product CFTR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9262–9266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trezise AE, Buchwald M. In vivo cell-specific expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Nature. 1991;353:434–437. doi: 10.1038/353434a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright EM, Hirayama BA, Loo DF. Active sugar transport in health and disease. J Intern Med. 2007;261:32–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flotte TR, et al. Phase I trial of intranasal and endobronchial administration of a recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 2 (rAAV2)-CFTR vector in adult cystic fibrosis patients: A two-part clinical study. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1079–1088. doi: 10.1089/104303403322124792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.High KA. AAV-mediated gene transfer for hemophilia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;953:64–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb11361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lai Y, et al. Efficient in vivo gene expression by trans-splicing adeno-associated viral vectors. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1435–1439. doi: 10.1038/nbt1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ostedgaard LS, Baldursson O, Vermeer DW, Welsh MJ, Robertson AD. A functional R domain from cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is predominantly unstructured in solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5657–5662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100588797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baker JM, et al. CFTR regulatory region interacts with NBD1 predominantly via multiple transient helices. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:738–745. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Charizopoulou N, et al. Spontaneous rescue from cystic fibrosis in a mouse model. BMC Genet. 2006;7:18–32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ostedgaard LS, Zeiher B, Welsh MJ. Processing of CFTR bearing the P574H mutation differs from WT and deltaF508-CFTR. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2091–2098. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.13.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meyerholz DK, Stoltz DA, Pezzulo AA, Welsh MJ. Pathology of gastrointestinal organs in a porcine model of cystic fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2010;3:1377–1389. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeiher BG, et al. A mouse model for the delta F508 allele of cystic fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2051–2064. doi: 10.1172/JCI118253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]