Abstract

Our previous data have linked obesity with immune dysfunction. It is known that physical exercise with dietary control has beneficial effects on immune function and the comorbidities of obesity. However, the mechanisms underlying the improvement of immune function in obesity after physical exercise with dietary control remain unknown. Here we show that moderate daily exercise with dietary control restores the impaired cytokine responses in diet-induced obese (DIO) mice and improves the resolution of Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced periodontitis. This restoration of immune responses is related to the reduction of circulating free fatty acids (FFAs) and TNF. Both FFAs and TNF induce an Akt inhibitor, carboxyl-terminal modulator protein (CTMP). The expression of CTMP is also observed increased in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMΦ) from DIO mice and restored after moderate daily exercise with dietary control. Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), which increases CTMP induction by FFAs, is inhibited in BMMΦ from DIO mice or after either FFA or TNF treatment, but unexpectedly is not restored by moderate daily exercise with dietary control. Furthermore, BMMΦ from DIO mice display reduced histone H3 (Lys-9) acetylation and NF-κB recruitment to TNF, IL-10, and TLR2 promoters after P. gingivalis infection. However, moderate daily exercise with dietary control restores these defects at promoters for TNF and IL-10, but not for TLR2. Thus, metabolizing FFAs and TNF by moderate daily exercise with dietary control improves innate immune responses to infection in DIO mice via restoration of CTMP and chromatin modification.

Keywords: innate immunity, bacteria clearance, Akt pathway

Excessive energy intake and sedentariness are prominent risk factors for becoming overweight and developing obesity (1, 2). Obesity is a predisposing risk factor for many health problems, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, atherosclerosis, diabetes, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, periodontal disease, certain cancers, and asthma (3–6). Changes in immune functions have been proposed as underlying the pathogenesis of all these diseases. Obesity induces immune defects that lead to attenuated host responses to infection (7–9). The combination of dietary and exercise interventions has been proved to provide the most beneficial effects to obese people (10–12). However, few studies have addressed the molecular mechanisms involved in the restoration of obesity-induced immune defects.

We previously demonstrated that diet-induced obesity (DIO) inhibited the ability of the immune system to appropriately respond to Porphyromonas gingivalis infection and concluded that this immune dysregulation participated in the increased alveolar bone loss from bacterial infections observed in DIO mice (7). Both free fatty acids (FFAs) and TNF are elevated in obesity and are important parameters for the comorbidities of obesity (13–16). FFAs activate toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated inflammatory signaling pathways and induce TNF expression in DIO mice (16).

In contrast, TLR2, which negatively modulates the TNF expression induced by FFAs, is dysfunctional in macrophages from DIO mice (9). Feeding mice a high-fat diet (HFD) over time elevates the intracellular pool of a key innate immune inhibitory molecule, carboxyl-terminal modulator protein (CTMP), which inhibits Akt phosphorylation and attenuates innate immune responses in macrophages from DIO mice. The induction of CTMP is achieved initially via FFAs activating TLR2 and later when the defective TLR2 is unable to inhibit TNF-α–induced CTMP (9). Therefore, the elevation of CTMP by FFAs and TNF together with the disruption of TLR2 in macrophages is the key factor for the impairment of innate immune function in DIO mice. In the present study, we tested whether imposing a regimen of moderate daily exercise with dietary control can restore in vivo innate immune responses to bacterial infection and bone loss in DIO mice. Furthermore, we also tested in vitro whether this regimen can restore TLR2 signaling pathways shown to be aberrant after DIO.

Results

In Vivo Studies.

To assess the effect of moderate daily exercise with dietary control on obesity and infection, four groups of mice were selected: (i) standard chow diet (SCD)-fed lean mice (LN/SCD); (ii) HFD-induced obese mice (OB/HFD); (iii) OB/HFD mice subjected to moderate daily exercise and kept on HFD for 4 wk (OB/HFD/Ex); and (iv) OB/HFD mice subjected to moderate daily exercise and a switch to SCD for 4 wk (OB/SCD/Ex).

Moderate daily exercise with dietary control reduces serum FFAs levels and restores cytokine responses in DIO mice.

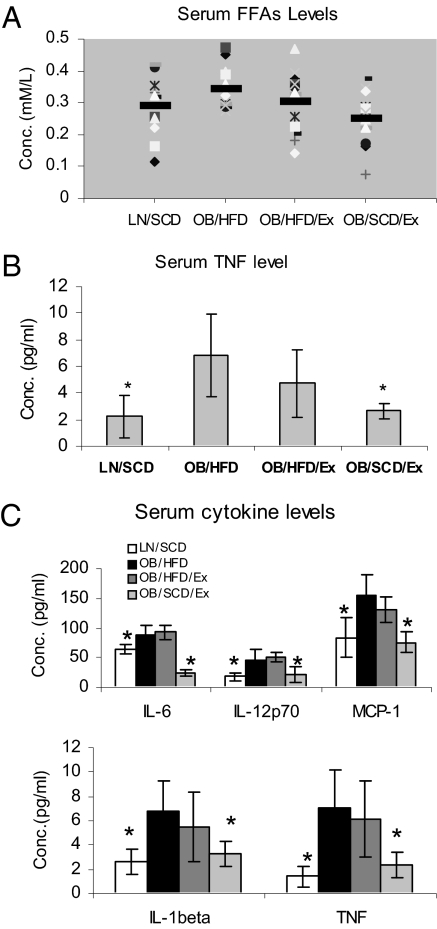

FFAs levels are elevated in obese individuals and may contribute to the chronic inflammatory state in obesity (9, 17–19). To determine whether moderate daily exercise with dietary control reduces FFA levels in DIO mice, we investigated their levels in LN/SCD, OB/HFD, OB/HFD/Ex, and OB/SCD/Ex mice. The body weight of OB/HFD/Ex and OB/SCD/Ex mice was significantly reduced after moderate daily exercise, regardless of whether or not their diet was changed (Table 1); meanwhile, the fasting blood glucose levels in the mice of all groups remained in normal range (<125 mg/dL; Table 2). The fasting serum FFA levels in OB/HFD mice were significantly higher than those in LN/SCD mice (P = 0.04); however, the FFA levels observed in OB/SCD/Ex mice (P = 0.003), but not in OB/HFD/Ex mice (P = 0.21), were reduced compared with OB/HFD mice (Fig. 1A). Similarly, the serum TNF levels were higher in OB/HFD mice than in LN/SCD mice (P = 0.002), whereas the serum TNF levels were reduced in OB/SCD/Ex mice (P = 0.002) but not in OB/HFD/Ex mice (P = 0.155; Fig. 1B). Furthermore, moderate daily exercise with dietary control also restored MCP-1, IL-12p70, IL-6, and IL-1β levels in OB/SCD/Ex mice as compared with OB/HFD mice (Fig. 1C).

Table 1.

Mouse body weight before and after exercise

| Mouse body weight, g (n = 20) |

|||

| Treatment group | Before Ex | After Ex | P |

| LN/SCD | 31.5 ± 2.1 | 32.9 ± 1.6 | 0.0333 |

| OB/HFD | 47.6 ± 2.2 | 49.3 ± 3.1 | 0.135 |

| OB/HFD/Ex | 48.0 ± 4.0 | 40.4 ± 5.2 | 0.0004 |

| OB/SCD/Ex | 47.8 ± 4.2 | 34.3 ± 3.8 | 0.00E + 00 |

Table 2.

Blood glucose levels before and after exercise

| Fasting blood glucose, mg/dL (n = 20) |

|||

| Treatment group | Before Ex | After Ex | P |

| LN/SCD | 95.1 ± 19.8 | 103.5 ± 16.3 | 0.1594 |

| OB/HFD | 99.5 ± 24.9 | 113.1 ± 13.6 | 0.0656 |

| OB/HFD/Ex | 98.3 ± 21 | 103.8 ± 15.8 | 0.3638 |

| OB/SCD/Ex | 100.1 ± 21.6 | 103.5 ± 12.3 | 0.6026 |

Fig. 1.

Moderate daily exercise with dietary control reduces serum FFAs and cytokine levels in DIO mice. Sera from submandibular vein blood was obtained from LN/SCD, OB/HFD, OB/HFD/Ex, and OB/SCD/Ex mice. (A) Fasting FFAs were measured by using NEFA-HR (2) reagents. (B) TNF levels in serum were measured by ELISA. (C) Serum cytokines were measured by Bio-Plex array. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 20; *P < 0.05).

Moderate daily exercise with dietary control restores the impaired cytokine responses in DIO mice to systemic P. gingivalis infection.

We tested whether moderate daily exercise with dietary control could restore the cytokine responses to systemic P. gingivalis infection in DIO mice. After moderate daily exercise with dietary control for 4 wk, mice were repeatedly infected with live P. gingivalis by tail vein injection. On day 5 after infection, substantial attenuation of TNF, MCP-1, IL-12p70, IL-6, and IL-1β responses was observed in OB/HFD mice as compared with LN/SCD mice. After moderate daily exercise with dietary control, the responses of TNF, MCP-1, IL-12p70, IL-6, and IL-1β were restored in OB/SCD/Ex mice toward normal levels seen in LN/SCD mice (Fig. 2). However, on day 10 after infection, the TNF and IL-1β responses to P. gingivalis infection were even stronger in OB/HFD mice than those in LN/SCD or OB/Ex/SCD mice. In contrast, the MCP-1 and IL-12p70 responses consistently remained weaker in OB/HFD mice than those in LN/SCD or OB/SCD/Ex mice for as long as 10 d after P. gingivalis infection, even though the baseline levels of these cytokines were higher in OB/HFD mice than those in LN/SCD or OB//SCD/Ex mice (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Moderate daily exercise with dietary control restores cytokine responses in DIO mice. Mice from LN/SCD, OB/HFD, and OB//ACD/Ex groups were challenged i.v. with live P. gingivalis on days 1, 3, and 5. Venous blood was collected on days 0, 5, and 10. Cytokine levels were tested using Bio-Plex luminex assay. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 13; *P < 0.05).

Moderate daily exercise with dietary control restores the impaired immune defense in DIO mice against P. gingivalis local infection.

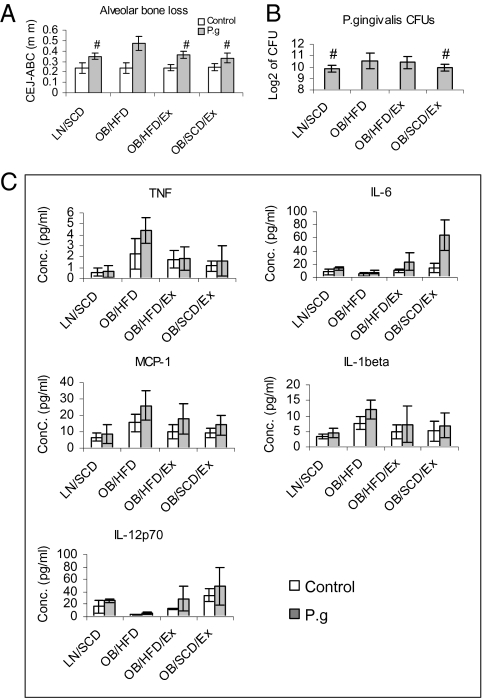

We induced experimental periodontitis by wrapping P. gingivalis-soaked ligatures around the maxillary second molar (20) in the four described groups. P. gingivalis-infected OB/HFD mice showed a 34% increase in alveolar bone loss compared with the LN/SCD group (P = 0.001), whereas OB/HFD/Ex mice and OB/SCD/Ex mice exhibited a 27% and 42% decrease in alveolar bone loss, respectively, compared with the OB/HFD group (Fig. 3A). No significant differences in alveolar bone loss were observed in uninfected mice among the four groups. In addition, higher titers of P. gingivalis were observed in plaque samples from OB/HFD mice compared with LN/SCD mice on day 10 after periodontitis (P = 0.036). The titers were decreased in OB/SCD/Ex mice (P = 0.050), but not in OB/HFD/Ex mice (P = 0.364), compared with OB/HFD mice (Fig. 3B). To determine the systemic inflammation in mice after P. gingivalis-induced periodontitis, serum TNF, MCP-1, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-12p70 levels of the four groups of mice were quantified by Bio-Plex cytokine array (Bio-Rad). OB/HFD mice exhibited higher levels of TNF, MCP-1, and IL-1β, and lower levels of IL-6 and IL-12p70, in the sera, as compared with LN/SCD or OB/SCD/Ex mice (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Moderate daily exercise with dietary control improves P. gingivalis-induced periodontitis. Mice from LN/SCD, OB/HFD, OB/HFD/Ex, and OB/SCD/Ex groups were exposed to P. gingivalis-soaked or broth-soaked ligatures. After three challenges with bacteria or broth alone, mice were euthanized. Blood, subgingival samples, and bone tissue were prepared and analyzed by Bio-Plex cytokine assay, bacterial culture, and morphometric analysis, respectively. (A) Distance from the cemental enamel junction (CEJ) to the alveolar bone crest (ABC) was measured in millimeters. (B) Log of the number of P. gingivalis CFUs from subgingival samples 3 d after the last ligature removal. (C) Cytokine levels in sera 3 d after the last ligature removal. The data presented are means ± SEM (n = 5 mice for each group). *P < 0.05 (P. gingivalis vs. control); #P < 0.05 (OB/HFD vs. other groups).

In Vitro Studies.

Moderate daily exercise with dietary control restores macrophage cytokine responses to P. gingivalis infection.

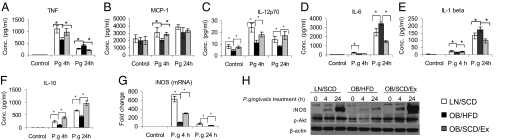

To investigate whether moderate daily exercise with dietary control improves the innate immune responses of macrophages in OB/HFD mice, bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMΦ) isolated from LN/SCD, OB/HFD, and OB/SCD/Ex mice were stimulated ex vivo with P. gingivalis for 4 or 24 h or remained unchallenged. The cell culture supernatants were analyzed for cytokine responses either by Bio-Plex cytokine array (TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12p70, and MCP-1) or by ELISA (IL-10). After 4 h infection, TNF, MCP-1, IL-12p70, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 levels were significantly reduced in BMMΦ from OB/HFD mice compared with BMMΦ from LN/SCD mice. After moderate daily exercise with dietary control, these cytokines were restored in BMMΦ from OB/SCD/Ex mice (Fig. 4A–F). However, 24 h after infection, TNF, IL-6, and IL-1β secretion from OB/HFD BMMΦ were significantly increased when compared with their release from LN/SCD or OB/SCD/Ex mice. The IL-12p70 and IL-10 responses remained weaker in BMMΦ from OB/HFD mice than in BMMΦ from LN/SCD or OB/SCD/Ex mice.

Fig. 4.

Moderate daily exercise with dietary control restores macrophage innate immune responses. BMMΦ from LN/SCD, OB/HFD, and OB/SCD/Ex mice were stimulated with or without live P .gingivalis for 4 and 24 h. (A–F) Cell culture supernatants were collected, and cytokines were measured by Bio-Plex luminex assay (TNF, MCP-1, IL-12p70, IL-6, and IL-1β) or by ELISA (IL-10). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4; *P < 0.05). (G) iNOS mRNA levels were measured by real-time PCR using total RNA. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4; *P < 0.05). (H) Whole-cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis using antibodies against iNOS, phospho-Akt (Ser473), and β-actin. Depicted are the results from one of three representative independent experiments.

Moderate daily exercise with dietary control restores macrophage iNOS induction and Akt phosphorylation.

Because BMMΦ from OB/HFD mice have been reported to exhibit impairment of inducible NOS (iNOS) induction and Akt phosphorylation after P. gingivalis infection (9), we tested whether moderate daily exercise with dietary control could restore iNOS and Akt in BMMΦ. Indeed, after 4 or 24 h of P. gingivalis infection, the induction of iNOS mRNA in BMMΦ from OB/HFD mice was much lower than that in BMMΦ from LN/SCD mice and only partially restored in BMMΦ from OB/SCD/Ex mice (Fig. 4G). The induction of iNOS protein was also reduced in BMMΦ from OB/HFD mice, but fully recovered in BMMΦ from OB/SCD/Ex mice (Fig. 4H). Similarly, Akt phosphorylation was inhibited in BMMΦ from OB/HFD mice, and moderate daily exercise with dietary control restored both baseline and P. gingivalis-induced Akt phosphorylation in BMMΦ from OB/SCD/Ex mice (Fig. 4H).

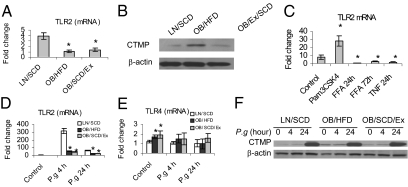

Moderate daily exercise with dietary control reduces CTMP but does not restore TLR2 expression.

We demonstrated previously that TLR2 was decreased and CTMP was increased in BMMΦ from DIO mice and that these changes resulted in innate immune inhibition in the BMMΦ (9). To test whether moderate daily exercise with dietary control restores TLR2 and CTMP levels, we investigated their expression in BMMΦ from LN/SCD, OB/HFD, and OB/SCD/Ex mice. The regimen of moderate daily exercise with dietary control did not restore the baseline TLR2 mRNA expression (Fig. 5A), but it reduced the protein level of CTMP in BMMΦ from OB/SCD/Ex mice (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Moderate daily exercise with dietary control affects TLR2 and CTMP expression in DIO mice. (A and B) BMMΦ from LN/SCD, OB/HFD, and OB/SCD/Ex mice left untreated and total RNA or proteins were isolated. The mRNA level of TLR2 was measured by real-time PCR (A), and the CTMP level was detected by Western blot (B). (C) BMMΦ from 6-wk-old C57BL/J mice were stimulated with TLR2 agonist Pam3CSK4 (1 μg/mL), FFAs, or TNF (10 ng/mL) for indicated time; the TLR2 mRNA level was measured by real-time PCR. (D–F) BMMΦ from LN, OB, and OB/SCD/Ex mice were challenged with P. gingivalis for 4 or 24 h or left unchallenged. The mRNA levels for TLR2 (D) and TLR4 (E) in BMMΦ were measured by real-time PCR, and protein levels for CTMP were tested by Western blot (F). Data for mRNA are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3; *P < 0.05). Each Western blot result represents three independent experiments.

To determine whether the suppression of TLR2 in DIO mice was due to elevated levels of FFAs or TNF in serum, we treated BMMΦ from 6-wk-old C57BL/J mice with 400 μM FFAs, 10 ng/mL of TNF, or 1 μg/mL of the TLR2 agonist Pam3CSK4 (InvivoGen) for indicated time courses. We found that TLR2 mRNA levels were highly induced by 24-h stimulation with Pam3CSK4. However, TLR2 expression was significantly inhibited by either FFA or TNF treatment (Fig. 5C).

To explore the dynamic changes of TLR2 and CTMP in BMMΦ from LN/SCD, OB/HFD, and OB/SCD/Ex mice following the course of P. gingivalis infection, we found that the induction of TLR2 mRNA by P. gingivalis was strongly elevated in BMMΦ from LN/SCD mice after 4 h infection, but dropped sharply after 24 h (Fig. 5D). A substantial inhibition of TLR2 mRNA in BMMΦ from OB/HFD mice was observed after either 4- or 24-h infection. After moderate daily exercise with dietary control, the TLR2 expression was not recovered in OB/SCD/Ex mice (Fig. 5D). Although TLR4 mRNA levels were slightly increased in uninfected BMMΦ from OB/HFD and OB/SCD/Ex mice, its expression levels were not significantly changed among BMMΦ from LN/SCD, OB/HFD, and OB/SCD/Ex mice after P. gingivalis infection for either 4 or 24 h (Fig. 5E). The baseline CTMP level remained higher in BMMΦ from OB/HFD mice than that in BMMΦ from LN/SCD or OB/Ex/SCD mice. However, CTMP in BMMΦ from all four groups of mice is not induced by P. gingivalis at the early stage of infection (4 h), whereas it is strongly induced in all groups of BMMΦ after 24 h infection with P. gingivalis (Fig. 5F).

Moderate daily exercise with dietary control affects chromatin modification.

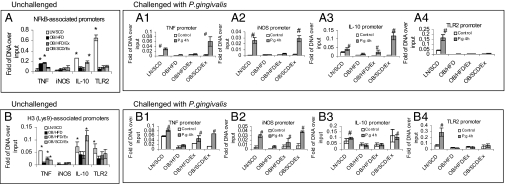

We first tested the differential recruitment of NF-κB (p65) at specific promoters for TNF, iNOS, IL-10, and TLR2 among BMMΦ from LN/SCD, OB/HFD, OB/HFD/Ex, and OB/SCD/Ex mice. Indeed, the moderate daily exercise with dietary control significantly decreased NF-κB (p65) binding to TNF promoter and increased NF-κB (p65) binding to IL-10 promoter, but it has little effect on NF-κB (p65) binding to iNOS and TLR2 promoters in untreated BMMΦ from DIO mice (Fig. 6A). However, after BMMΦ infection with P. gingivalis for 4 h, the recruitment of NF-κB (p65) to TNF, iNOS, and IL-10 promoters, but not to TLR2 promoter, was significantly restored in BMMΦ from OB/SCD/Ex mice compared with BMMΦ from OB/HFD mice (Fig. 6 A1–4).

Fig. 6.

Moderate daily exercise with dietary control affects chromatin modifications. BMMΦ from LN/SCD, OB/HFD, OB/HFD/Ex, and OB/SCD/Ex mice were either left untreated or were treated with P. gingivalis for 4 h. ChIP assays were performed by using antibodies against NF-κB (p65) and acetyl-Histone 3 (Lys-9). Antibody-precipitated DNA was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR with promoter-specific primers amplifying the TLR2, iNOS, TNF, and IL-10 promoters. (A) Recruitment of NF-κB to gene promoters in unchallenged BMMΦ. (A1–A4) Recruitment of NF-κB to TNF (A1), iNOS (A2), IL-10 (A3), and TLR2 (A4) promoters after P. gingivalis challenge. (B) Recruitment of acetyl-Histone 3 to gene promoters in unchallenged BMMΦ. (B1–B4) Recruitment of acetyl-Histone 3 to TNF (B1), iNOS (B2), IL-10 (B3), and TLR2 (B4) promoters after P. gingivalis challenge. The results are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 4; *P < 0.05, other groups vs. OB of untreated cells; #P < 0.05, other groups vs. OB of infected cells).

Because histone acetylation has a key role in opening chromatin for gene transcription, we further investigated whether the differential recruitment of NF-κB (p65) in BMMΦ was due to changes in histone acetylation in DIO mice. ChIP data in untreated BMMΦ revealed that DIO dramatically reduced histone H3 acetylation at Lys-9 in the promoters for TNF, IL-10, and TLR2, and this reduction is restored in the promoters for TNF and IL-10—but not for TLR2—after moderate daily exercise with dietary control (Fig. 6B). When BMMΦ were infected with P. gingivalis for 4 h, the histone H3 acetylation at Lys-9 in the promoters for TNF, iNOS, and IL-10 was more strongly induced in BMMΦ from LN/SCD or OB/SCD/Ex mice than that in BMMΦ from OB/HFD mice. However, moderate daily exercise with or without dietary control did not restore the induction of H3 acetylation at the promoter for TLR2 in BMMΦ after P. gingivalis infection (Fig. 6 B1–4).

Discussion

Recent studies using animal models of DIO have identified concomitant immune dysfunction (7–9, 21, 22). Although physical exercise with dietary control has been shown to improve immune function (23), the mechanisms whereby moderate daily exercise with dietary control restores immune function in DIO mice are relatively uninvestigated. The present results confirm that mice with DIO exhibit a delayed resolution of inflammation and show that the regimen of moderate daily exercise with dietary control exerts a beneficial effect on inflammation. This beneficial effect results from the fact that this regimen reduced circulating FFA and TNF levels, reversed the aberrant inflammatory pathways, and restored histone acetylation in DIO mice.

In our model of DIO mice, the effect of moderate daily exercise with dietary control was surprisingly dramatic. After moderate daily exercise with dietary control, mice with DIO exhibited significant restoration of cytokine responses to chronic P. gingivalis infection. Accompanying the restoration of cytokine responses was a reduction of alveolar bone loss together with diminished bacterial titers in plaque samples in P. gingivalis-induced periodontal disease. The improved cytokine responses were observed in all serum samples, whether after direct systemic inoculation or after oral inoculation of P. gingivalis.

We hypothesized that the improvement of cytokine responses after moderate daily exercise with dietary control might be a consequence of the reduction of circulating FFA and TNF levels in DIO mice. The plausibility of this hypothesis is based on the following evidence. First, physical exercise promotes the utilization of FFAs in muscles and decreases their levels in well-controlled diabetic patients (24, 25). Secondly, FFAs have been reported to induce TLR4-mediated inflammation in tissues and cause macrophage tolerance to bacterial infection (9, 15, 16). In addition, FFAs are known to inhibit TLR2 expression, which leads to an uncontrolled TNF induction by FFAs (9). Finally, both FFAs and TNF were found to induce a disruption of cytokine profile, causing attenuated innate immune responses to bacterial infection (7–9, 21, 22). Together, metabolizing FFAs and TNF by moderate daily exercise with dietary control may restore the aberrant cytokine profile and innate immune responses in DIO mice.

Our results show that the cytokine profile of DIO mice is restored to levels comparable with lean mice after moderate daily exercise with dietary control, whether animals were challenged with the infectious agent systemically or locally. However, the cytokine responses were not uniform. Although the responses of TNF and IL-1β were restored in chronic infection after moderate daily exercise with dietary control, the responses of IL-6 and IL-12p70 were enhanced. The decrease of TNF and IL-1β in chronic infection after moderate daily exercise with dietary control may stem from the reduction in tissue destruction in P. gingivalis-induced periodontitis; the increase of IL-6 and IL-12p70 is viewed to contribute to activate NK cells and T lymphocytes (26, 27) that can facilitate the resistance against bacterial infections (28)—possibly explaining the restoration by this regimen of the defective bacterial clearance found in DIO mice (7). Furthermore, dietary control is required in addition to exercise for restoring the baseline level of TNF and the ability of bacterial clearance. This may be due to the fact that exercise only is ineffective in reducing circulating FFA levels, whereas the oral environment facilitates bacteria growth while the animals are kept on HFD. However, the regimen of moderate daily exercise not only does not affect TNF levels but also increases IL-6 levels in chronic P. gingivalis infections consistent with the known increase in circulating levels of IL-6 after exercise without muscle damage (29). The increase of IL-6 may have a suppressive effect on TNF expression, and further leads to significant reduction of alveolar bone loss during chronic P. gingivalis-induced periodontitis.

Given that FFA- and TNF-induced CTMP blocks Akt phosphorylation and attenuates cytokine and iNOS responses to infection (9), the finding that CTMP levels returned to normal values in BMMΦ after moderate daily exercise with dietary control indicates that the restoration of Akt phosphorylation, iNOS expression, and cytokine responses in BMMΦ from DIO mice after moderate daily exercise with dietary control is at least in part due to the restoration of CTMP expression, followed by the decrease of FFAs and TNF.

Histone acetylation is a key modification that regulates chromatin accessibility. We found that when BMMΦ were infected with P. gingivalis, histone acetylation at promoters for TNF, iNOS, IL-10, and TLR2 was impaired by DIO. Correspondingly, the recruitment of NF-κB to those promoters was also decreased in BMMΦ from DIO mice when compared with lean mice. Therefore, the decreased NF-κB recruitment to those promoters is most likely due to the impaired histone acetylation. However, the impaired histone acetylation and NF-κB recruitment to promoters for TNF, iNOS, and IL-10, but not for TLR2, are restored after moderate daily exercise with dietary control. Thus, the restoration of histone acetylation on the promoters may play an important role in restoring the innate immune responses to P. gingivalis infection in DIO mice. Concerning TLR2 promoter, additional chromatin modification such as hyperlipidemic lipoprotein-associated aberrant DNA methylation (30) may have interfered with histone acetylation, thereby impairing the recovery of TLR2 expression. The impaired histone acetylation in DIO mice might result from FFA- and TNF-induced epigenetic changes on gene promoters causing a low NF-κB binding to gene promoters (31).

Moderate daily exercise with dietary control results in the improvement of host immune responses through multiple molecular mechanisms. Although this restoration was observed with imposed diet control and exercise, human obesity involves important complex behavioral factors that affect diet choices and exercise. Given that human obesity remains a notable epidemic with public heath implications, the present results provide further impetus for obese individuals to scale up efforts for a self-imposed regimen of exercise and control of diet.

Materials and Methods

All measurements and assessment were performed by individuals blinded to all groups.

Animals and Treatments.

C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories) were housed at the Boston University Medical Center Animal Facility. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee. DIO mice were developed according to previous studies (7, 9). Exercise training was performed on an Exer-6M treadmill (Columbus Instruments) 5 d/wk, 1 h/d in the morning (9:00 AM to 12:00 PM) for 4 wk at the speed of 12 m/min. Mice were shocked with a 1-Hz electric pulse to keep them exercising. Three days after the end of exercise, in vivo experiments and BMMΦ isolation were performed. The body weight and blood glucose concentration after overnight fasting were monitored before and after exercise. Blood glucose level was measured in tail vein blood by using the Freestyle blood glucose monitor (Abbott Laboratories). Animals with serum glucose levels of >125 mg/dL before exercise were excluded. Fasting FFAs in serum were measured using NEFA-HR-2 reagents (Wako Chemicals).

Bacterial Infection.

P. gingivalis (A7436; American Type Culture Collection) was anaerobically cultured in brain–heart infusion (BHI) broth (32). Periodontitis was induced by tying P. gingivalis-soaked 5-0 silk ligature around the maxillary right and left second molars (20). The individual placing the ligatures was blinded to all of the treatment groups. Ligatures were placed on day 1, changed on days 3 and 5, and then removed on day 7. All mice were euthanized at day 10, and maxillary jaw bones and sera were collected for morphometric analysis and cytokine assay, respectively. Corresponding controls received ligatures precultured in sterile BHI medium without P. gingivalis, as did the infected groups. For systemic infection, mice were repeatedly infected i.v. with P. gingivalis A7436 by tail vein injection (7). Venous blood was collected on days 0, 5, and 10 via the submandibular vein (33).

Cytokine Measurement.

Concentrations of cytokines in sera or cell culture supernatants were measured by using Bio-Plex Luminex assay (7). TNF and IL-10 levels were determined using BD Bioscience-PharMingen ELISA kits.

Measurement of Bone Loss.

Bone loss around the roots of mouse teeth (alveolar bone) was measured by morphometric analysis on six tooth aspects: mesio-buccal (MB), midbuccal (MidB), disto-buccal (DB), disto-palatal (DP), midpalatal (MidP), and mesio-palatal (MP), as described (20). Measurements were made under a dissecting microscope (magnification: 40×) fitted with a video image marker measurement system (Image-Pro Plus, Version 6.0) standardized to give measurements in millimeters. Bone measurements were obtained in triplicate in a random and blinded fashion by two evaluators. All measurements were made on images taken with the three molar teeth being on the same occlusal plane;

Quantitation of Bacterial Titers.

Subgingival plaque samples of left and right maxillary second molars were collected by using sterile paper points after completion of the ligature phase on day 10. The plaque samples were plated for aerobe and anaerobe plaque analysis as described (7, 20).

Macrophage Isolation and Treatment.

BMMΦ was isolated from hind legs of mice and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (19, 34). BMMΦ was infected with P. gingivalis A7436 with multiplicities of infection of 10:1 (32). BMMΦ was treated with FFAs, TNF, and Pam3 as described (7).

RNA Preparation and Quantitative Real-Time PCR.

Total RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and real-time PCR were conducted as described (35).

Western Blot.

Western blots were performed using antibodies against p-Akt (Ser-473), CTMP, PPAR-γ (all from Cell Signaling), iNOS, β-actin, and HRP-conjugated IgG (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP).

Chromatin from BMMΦ was isolated from fixed cells and sheared enzymatically by using ChIP-IT Express Kits (Active Motif). ChIP assays were performed by using antibodies against NF-κB (p65) or histone H3 (Lys-9) as described (9). The specific primers for ChIP assay were TNF promoter (sense: 5′-tggaggaagtggctgaag; antisense: 5′-aggagaaggcttgtgagg), iNOS promoter (sense: 5′-gcaggactacagtggacag; antisense: 5′-caagtgaggaggcggagg), IL-10 promoter (sense: 5′-tactaacatctccatccttcaac; antisense: 5′-gttctggtgcctcctctg), and TLR2 promoter (sense: 5′-ttggtcaaggtgtgctatc; antisense: 5′-tctctttggttattggaatgc).

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed by using JMP statistical software (SAS Institute). Normally distributed data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with diet and infection as main effects. Student's t test was used for post hoc comparison between the dietary groups. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Grant DE15989 (to S.A.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jebb SA, Moore MS. Contribution of a sedentary lifestyle and inactivity to the etiology of overweight and obesity: Current evidence and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(11, Suppl):S534–S541. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199911001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prentice AM, Jebb SA, Black AE. Extrinsic sugar as vehicle for dietary fat. Lancet. 1995;346:697–698. 346:695 and author reply (1995) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalla Vecchia CF, Susin C, Rösing CK, Oppermann RV, Albandar JM. Overweight and obesity as risk indicators for periodontitis in adults. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1721–1728. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.10.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linden G, Patterson C, Evans A, Kee F. Obesity and periodontitis in 60-70-year-old men. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:461–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miranda PJ, DeFronzo RA, Califf RM, Guyton JR. Metabolic syndrome: definition, pathophysiology, and mechanisms. Am Heart J. 2005;149:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miranda PJ, DeFronzo RA, Califf RM, Guyton JR. Metabolic syndrome: evaluation of pathological and therapeutic outcomes. Am Heart J. 2005;149:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amar S, Zhou Q, Shaik-Dasthagirisaheb Y, Leeman S. Diet-induced obesity in mice causes changes in immune responses and bone loss manifested by bacterial challenge. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20466–20471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710335105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith AG, Sheridan PA, Harp JB, Beck MA. Diet-induced obese mice have increased mortality and altered immune responses when infected with influenza virus. J Nutr. 2007;137:1236–1243. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.5.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou Q, Leeman SE, Amar S. Signaling mechanisms involved in altered function of macrophages from diet-induced obese mice affect immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:10740–10745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904412106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lissin LW, et al. The prognostic value of body mass index and standard exercise testing in male veterans with congestive heart failure. J Card Fail. 2002;8:206–215. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2002.126812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woo KS, et al. Effects of diet and exercise on obesity-related vascular dysfunction in children. Circulation. 2004;109:1981–1986. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126599.47470.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart KJ. Exercise training and the cardiovascular consequences of type 2 diabetes and hypertension: Plausible mechanisms for improving cardiovascular health. JAMA. 2002;288:1622–1631. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.13.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tataranni PA, Ortega E. A burning question: Does an adipokine-induced activation of the immune system mediate the effect of overnutrition on type 2 diabetes? Diabetes. 2005;54:917–927. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu H, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1821–1830. doi: 10.1172/JCI19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boden G. Obesity and free fatty acids. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008;37:635–646. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2008.06.007. viii–ix. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi H, et al. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3015–3025. doi: 10.1172/JCI28898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pankow JS, et al. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study Fasting plasma free fatty acids and risk of type 2 diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:77–82. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mook S, Halkes CJM, Bilecen S, Cabezas MC. In vivo regulation of plasma free fatty acids in insulin resistance. Metabolism. 2004;53:1197–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen MT, et al. A subpopulation of macrophages infiltrates hypertrophic adipose tissue and is activated by free fatty acids via Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 and JNK-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35279–35292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li CH, Amar S. Morphometric, histomorphometric, and microcomputed tomographic analysis of periodontal inflammatory lesions in a murine model. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1120–1128. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mancuso P, Huffnagle GB, Olszewski MA, Phipps J, Peters-Golden M. Leptin corrects host defense defects after acute starvation in murine pneumococcal pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:212–218. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-909OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamas O, Martínez JA, Marti A. Energy restriction restores the impaired immune response in overweight (cafeteria) rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2004;15:418–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sim YJ, Yu S, Yoon KJ, Loiacono CM, Kohut ML. Chronic exercise reduces illness severity, decreases viral load, and results in greater anti-inflammatory effects than acute exercise during influenza infection. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1434–1442. doi: 10.1086/606014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato Y, Nagasaki M, Kubota M, Uno T, Nakai N. Clinical aspects of physical exercise for diabetes/metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77(Suppl 1):S87–S91. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donatelli M, et al. Effects of muscular exercise on erythrocyte adenosine triphosphate concentration in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Ric Clin Lab. 1987;17:343–347. doi: 10.1007/BF02886917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thierfelder WE, et al. Requirement for Stat4 in interleukin-12-mediated responses of natural killer and T cells. Nature. 1996;382:171–174. doi: 10.1038/382171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang KS, Frank DA, Ritz J. Interleukin-2 enhances the response of natural killer cells to interleukin-12 through up-regulation of the interleukin-12 receptor and STAT4. Blood. 2000;95:3183–3190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Poll T, et al. Interleukin-6 gene-deficient mice show impaired defense against pneumococcal pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:439–444. doi: 10.1086/514062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petersen AM, Pedersen BK. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1154–1162. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00164.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaina S, Døssing KB, Lindholm MW, Lund G. Chromatin modification by lipids and lipoprotein components: An initiating event in atherogenesis? Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16:549–553. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000180165.70077.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawson HA, et al. Genetic, epigenetic, and gene-by-diet interaction effects underlie variation in serum lipids in a LG/JxSM/J murine model. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:2976–2984. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M006957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou Q, Desta T, Fenton M, Graves DT, Amar S. Cytokine profiling of macrophages exposed to Porphyromonas gingivalis, its lipopolysaccharide, or its FimA protein. Infect Immun. 2005;73:935–943. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.935-943.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Golde WT, Gollobin P, Rodriguez LL. A rapid, simple, and humane method for submandibular bleeding of mice using a lancet. Lab Anim (NY) 2005;34:39–43. doi: 10.1038/laban1005-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper ZA, et al. Febrile-range temperature modifies cytokine gene expression in LPS-stimulated macrophages by differentially modifying NF-κB recruitment to cytokine gene promoters. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C171–C181. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00346.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou Q, Amar S. Identification of signaling pathways in macrophage exposed to Porphyromonas gingivalis or to its purified cell wall components. J Immunol. 2007;179:7777–7790. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]