Abstract

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) is a ring-shaped protein that encircles duplex DNA and plays an essential role in many DNA metabolic processes in archaea and eukarya. The eukaryotic and euryarchaea genomes contain a single gene encoding for PCNA. Interestingly, the genome of the euryarchaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis contains two PCNA-encoding genes (TK0535 and TK0582), making it unique among the euryarchaea kingdom. It is shown here that the two T. kodakaraensis PCNA proteins support processive DNA synthesis by the polymerase. Both proteins form trimeric structures with characteristics similar to those of other archaeal and eukaryal PCNA proteins. One of the notable differences between the TK0535 and TK0582 rings is that the interfaces are different, resulting in different stabilities for the two trimers. The possible implications of these observations for PCNA functions are discussed.

Keywords: DNA replication, three-dimensional structure

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) is an essential factor required for chromosomal DNA replication in archaea and eukarya. It is a ring-shaped trimeric complex that encircles DNA and upon binding to a replicative polymerase, tethers it to the DNA template for processive DNA synthesis (1, 2). In addition to their function as processivity factors for replicative polymerases, PCNA proteins from archaea and eukarya also associate and modulate the activities of a large number of other proteins involved in nucleic acid metabolic transactions (3). The archaea domain can be divided into three main branches: crenarchaeota, euryarchaeota, and thaumarchaeota. Although most archaea belonging to the euryarchaeota and thaumarchaeota branches encode a single PCNA gene that yields homotrimers, members of the crenarchaeota domain contain three distinct genes that result in the formation of heterotrimers as the active form (4, 5). In all eukarya studied, PCNA is a homotrimer.

Thermococcus kodakaraensis (TK), a hyperthermophilic euryarchaea that grows optimally at 85 °C, was isolated from a solfatara on the shore of Kodakara Island, Japan (6). It is an obligate heterotroph that grows on organic substrates usually in the presence of elemental sulfur that is reduced to hydrogen sulfide. Its genome contains 2.1 Mb with about 2,300 open reading frames (7). Interestingly, the TK genome contains two genes encoding for PCNA homologues (TK0535 and TK0582) with 54% identity (Fig. 1). As this is unique among euryarchaea, the three-dimensional structures of the two TK PCNA proteins were determined. It is shown here that both proteins form homotrimeric rings that stimulate DNA polymerase activity.

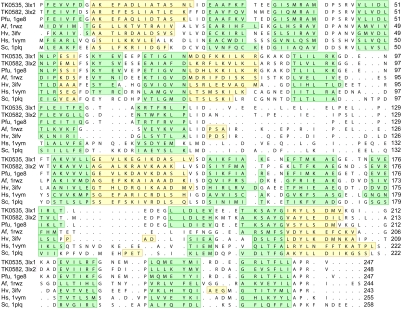

Fig. 1.

Structural alignment of archaeal and eukaryal PCNA proteins. Structural alignment of TK0535 with TK0582 and with PCNAs from P. furiosus (Pfu) (12), Archaeoglobus fulgidus (Af) (29), Haloferax volcanii (Hv) (30), Homo sapiens, (Hs) (31), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sc) (11). The residues on green background are β-strands, whereas those on yellow background are α-helical; loop regions and turns are on white background. The PDB ID codes are shown. This figure was composed using Chimera (32, 33).

Results

Overall Structures.

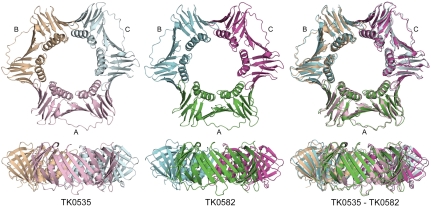

Both TK PCNAs form trimers that are rings of ∼90 Å in diameter with a ∼25 Å hole in the center and are ∼32 Å thick (Fig. 2). This architecture agrees with other known PCNA structures (8). Each protomer has two similar domains and each domain has two α-helices on the inside of the ring and two β-sheets on the outside. A long loop on the outside connects the two domains. The electron density for this loop is low in both structures and the B factors are quite high.

Fig. 2.

Representations of the TK0535 and TK0582 PCNA structures. Orthogonal views of TK0535 and TK0582 PCNA and of the superposition of the structures. For TK0535, the ABC trimer is pink, wheat, and light cyan. For TK0582, the ABC trimer is green, cyan, and magenta.

For TK0535, which crystallized in space group P63, the asymmetric unit contains a single protomer and the trimer is formed by crystal symmetry. For TK0582, which has three polypeptide chains in the asymmetric unit, the chains superimpose onto each other with rms deviations of 0.50–0.69 Å for the Cα positions. TK0535 superimposes on the three polypeptide chains of TK0582 with rms deviations of 1.2, 1.3, and 1.4 Å for the three chains. TK0535 and TK0582 superimpose onto the Pyrococcus furiosus (Pfu) PCNA structure that was used as the search model in molecular replacement with rms deviations of 0.6 and 1.0 Å, respectively.

Trimer Interfaces.

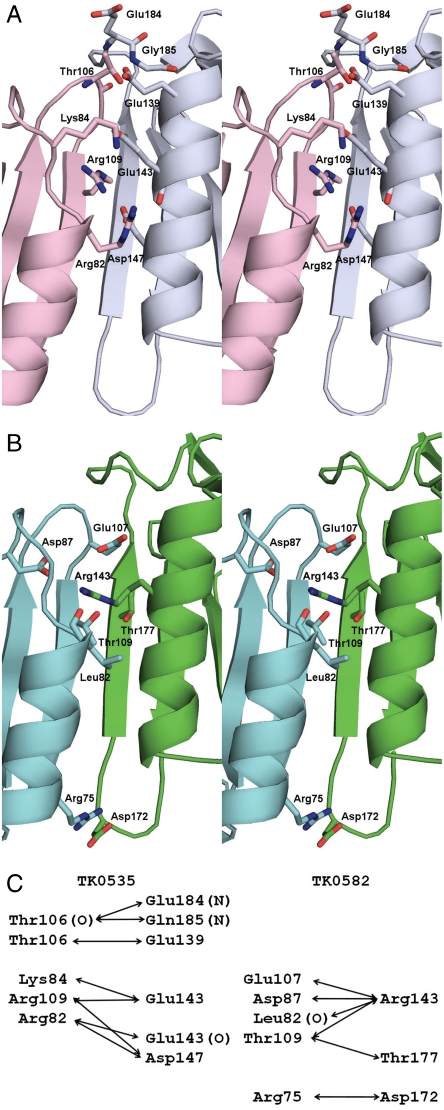

The basic features of the head-to-tail polypeptide chain interfaces like the overall architecture are conserved across prokarya, archaea, and eukarya (1, 8). The interface includes antiparallel β-strands forming an extended β-sheet, a core of hydrophobic residues, and varies mainly in the extent of hydrogen bonding, ion pairing, and the length of the β-strand interaction. The Web server PISA (9) was used to assist in the analysis of the interfaces. Both TK0535 and TK0582 PCNA structures display all of the features mentioned above and are consistent with other archaea in having trimer interfaces with more ionic character than the eukaryotic interfaces found in yeast and human PCNAs (10–12). The buried surface area of each TK0535 interface is 1,467 Å2, and the average buried surface area for the timer interfaces of TK0582 is 1,402 Å2. This is quite comparable to 1,436 Å2 for PfuPCNA. The sequences of TK0535 and PfuPCNA are 84% identical. Consequently, it is not surprising that the residues in the interface and the contacts are conserved between the two proteins (Fig. 3). Though both the core hydrophobic and antiparallel β-strand interactions detected in TK0535 and TK0582 are conserved, the side chains of the residues involved in these interactions are not. Differences in the two interfaces include hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions (Fig. 3). It has been suggested that the interface residues involved in ion pairs have a dual function contributing to the stability of the trimer and determining the head-to-tail alignment of the polypeptide chains (13). This group also suggested that these residues are highly conserved in thermophilic archaea and identified Arg82, Lys84, Arg109, Asp143, and Asp147 as key interface residues. TK0535 has these residues, except that residue 143 is glutamate instead of aspartate (Fig. 1). Although TK0582 has 53% sequence identity with PfuPCNA, the sequence identity of the residues involved in the interface surface is only 36% and, although the Cα position of the five residues mentioned above structurally superimpose, they are Leu82, Arg84, Thr109 in the head sequence and Arg143 and Ala147 in the tail sequence (Fig. 3). For TK0582 the principal H-bonding and ionic residues are Arg75, Asp87, Glu107, and Thr109 in the head sequence and Arg143, Asp172, and Thr177 in the tail sequence (Fig. 3). To propose a mixed trimer and replace the protomer on the right of the graph for TK0535 with the superposition of a protomer of TK0582 in Fig. 3C would place the positively charged residue Arg143 of TK0582 in the position of the negatively charged residue Glu143 of TK0535. This would necessitate significant rearrangements to avoid major ionic clashes and makes the presence of mixed trimers that preserve the PCNA tertiary architecture unlikely.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the interfaces of the TK0535 and TK0582 PCNA structures. (A) Stereo view of the interface of TK0535. (B) Stereo view of the interface of TK0582. In these stereo views, the residues involved in the hydrogen bonding and ion pair interactions are shown in stick representation. The backbone atoms are shown for the interactions involving a main chain nitrogen or oxygen. (C) Diagram of these interactions.

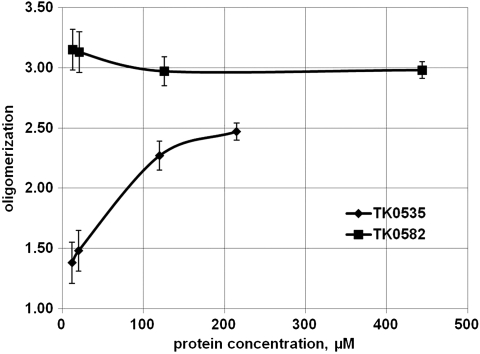

Furthermore, the two trimers have different stability (Fig. 4). At the concentration used for crystallization, 13 mg/mL, TK0582 gave a molar mass average of 87.0 kDa, which is close to the calculated molar mass of 87.8 kDa for a trimer. The experimental molar mass average for TK0535 at the concentration used for crystallization, 6.25 mg/mL, was 67.6 kDa, which is significantly low for a trimer (87.2 kDa) and significantly high for a dimer (58.1 kDa). When lower concentrations were used, the light scattering indicated that TK0582, under the solution conditions used, remained a stable trimer. Under the same conditions, the structure of TK0535 was most likely rapidly alternating between a dimer and a trimer at high concentrations and between dimer and monomer at lower concentrations. The different stabilities of the two PCNAs are also reflected in their ability to support DNA polymerase activity (described below).

Fig. 4.

TK0535 and TK0582 proteins’ oligomerization depend upon protein concentration. Static light scattering of dilution series of the two PCNAs demonstrate the stability of the trimer of TK0582 and the instability of the trimer of TK0535 at low protein concentrations.

Central Pore.

Typically, the inside surface of PCNA rings is positively charged with lysine and arginine residues. These residues are postulated to interact with the phosphate backbone of DNA through water-mediated interactions. Each TK0535 monomer has nine lysines and no arginines and TK0582 has seven lysines and three arginines extending into this space on each polypeptide chain, leading to a total of 27 and 30 positively charged residues in the center of the ring of the TK0535 and TK0582 structures, respectively. PfuPCNA has 30 lysines and no arginines lining its central core. Consequently, the positively charged central ring is conserved in both TK0535 and TK0582.

PCNA-Interacting Peptide (PIP-Box) Pocket.

It has been shown that many proteins involved in DNA processing and also in cell cycle regulation bind to PCNA through a conserved PIP-box motif of eight amino acids defined as Qxxhxxaa, where “h” is a moderately hydrophobic amino acid (I, L, or M) and “a” is an aromatic residue (3, 14). The glutamine interacts with the surface of the PCNA and the aromatic residues dock into a hydrophobic pocket that is near the long loop connecting the two domains. The superimposition of the PfuPCNA structure bound to an 11 residue peptide containing the PIP-box sequence of the large subunit of replication factor C (RFC) of Pfu (PDB ID code 1isq) (15) onto the structures of TK0535 and TK0582 shows that this binding pocket is conserved among these PCNAs.

Both TK0535 and TK0582 PCNA Stimulate the Activity of DNA Polymerase B (PolB).

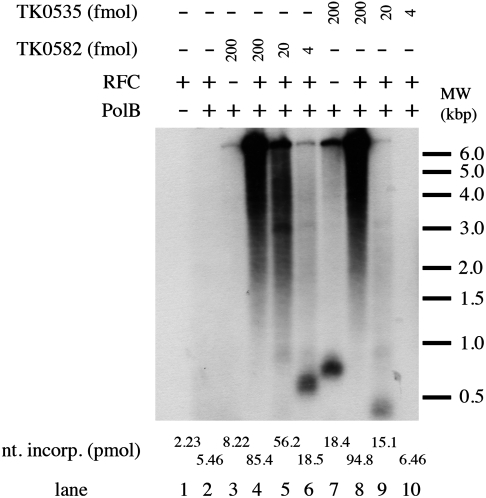

The best understood function for PCNA is its role as a processivity factor for DNA polymerases. Studies with eukarya and archaea have shown that while the processivity of the replicative polymerase is low, it can be increased dramatically in the presence of PCNA (1, 2, 16 and references therein). In order to determine if both TK PCNAs are active, replication assays were performed in the presence and absence of TK0535 and TK0582. These experiments were carried out in the presence of relatively high salt conditions (0.25 M NaCl) that prevent the TK DNA PolB from elongating primed templates in the absence of RFC and PCNA (data not presented). As shown in Fig. 5, the elongation of a singly primed M13 template by TK PolB was detected only in the presence of both RFC and PCNA (either TK0535 or TK0582). The rate of DNA synthesis in the presence of excess RFC depended on the level of PCNA added (Fig. 5, lanes 4–6 and 8–10). At lower TK0535 levels, the amount and size of DNA products formed were reduced (Fig. 5, lanes 9 and 10). This effect is likely due to the instability of the complex at low concentrations (Fig. 4). However, in the absence of RFC, the amount and size of DNA products that form in the presence of TK0535 were significantly greater in comparison to TK0582 (Fig. 5, compare lane 7 to lane 3).

Fig. 5.

TK0535 and TK0582 proteins stimulate the activity of PolB. Reaction mixtures (20 μL) were as described under Materials and Methods. Where indicated, 440 fmol of PolB, 430 fmol of TKRFC, and either 4 (lanes 6 and 10), 20 (lanes 5 and 9), or 200 (lanes 3, 4, 7 and 8) fmol of either TK0535 (lanes 7–10) or TK0582 (lanes 3–6) were added. Reactions were incubated for 20 min at 70 °C. An aliquot (4 μL) was used to measure DNA synthesis, and the remaining mixture was subjected to 1.1% alkaline-agarose gel electrophoresis. After drying, gels were autoradiographed for 15 min at -80 °C and then developed.

Discussion

The data presented here show that the two PCNAs present in TK, TK0535 and TK0582, have the structural and biochemical properties of PCNA molecules isolated from other archaea and eukarya. They are both homotrimers, form rings with helices and positively charged residues lining the center of the ring, display a hydrophobic pocket on the outer surface that aligns structurally with other PCNA structures that were solved with peptides containing the PIP-box consensus sequence, and stimulate polymerase activity. The main difference noted between the structures of TK0535 and TK0582 is the head-tail interface of the trimer.

The two distinct genes encoding PCNA can arise by gene duplication or lateral gene transfer from another organism. It is well established that following gene duplication, mutations in the duplicated molecules can occur followed by sequence drift. This could result in one active gene and one with altered activity. The three-dimensional structures revealed that the subunit interfaces of TK0535 and TK0582 are substantially different although both molecules are active. We believe that the two PCNA genes did not result from gene duplication as it is unlikely that compensating mutations at the interface occurred simultaneously at both surfaces. We think it is more likely that mutations occurring over time would result in one trimeric, functioning PCNA and one heavily mutated, probably a monomeric and nonfunctioning molecule because the selective pressure to keep both intact would be relatively low. Thus, the data suggest that one of the PCNA genes was acquired via lateral gene transfer. In support of this idea, when the genome of TK was completed, it was noted that the gene encoding for one of the two PCNA molecules, TK0582, is located in a region of the chromosome likely acquired via lateral gene transfer from a viral origin (7). Furthermore, the genome of TK is similar to that of Pyrococcus species. Thus, one would expect that the original TK PCNA protein will be more similar to that of Pyrococcus compared to the PCNA gene acquired via lateral gene transfer. This is indeed the case both in primary amino acid sequence and structural features. TK0535 is more similar to the PfuPCNA, as well as other archeael PCNA proteins, than is TK0582 (Fig. 1). Further support for lateral gene transfer comes from the observation that many of the genes encoding for PCNA are located in an operon with a gene encoding a subunit of the GINS complex (17). The gene encoding TK0535 is in an operon with the gene encoding for GINS but TK0582 is not.

Though the amino acid sequences of the two PCNAs and their contacts at the subunit interfaces differ, they both can be assembled around the DNA by RFC and stimulate polymerase activity (Fig. 5). Only one RFC complex has been identified in the TK genome. It is clear from the data that the single RFC complex can assemble both PCNA molecules. This is not surprising, however, as it was previously shown that RFC from one eukaryote can assemble PCNA from another (18) and that human RFC can assemble PfuPCNA around DNA (19). The data shown in Fig. 5 also indicate that both PCNA molecules stimulate the polymerase. This is similar to earlier work that showed that several archaeal PCNAs can stimulate mammalian DNA polymerases (19, 20) and the eukaryotic PCNA form one species can stimulate polymerases form different organisms (18).

Studies with the PCNA proteins from Pfu (19) and Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus (21) showed that the proteins can support limited polymerase activity in the absence of RFC as was shown here for TK0535 (Fig. 5, lane 7). Because TK0535 forms a less stable trimer in comparison to TK0582, it is possible that the TK0535 trimers in an open or linear state can encircle the DNA in an RFC independent manner. Upon assembly around the DNA they may be stabilized by ionic interaction with the DNA, possibly leading to a closed or circular form. As discussed above, TK0535 is more similar to other archaeal PCNA proteins. It is thus likely that the ability of other archaeal PCNAs to assemble around DNA in an RFC independent manner is also due to their limited stability at low protein concentrations.

Material and Methods

Cloning and Purification of the PCNA Proteins.

TK genomic DNA was used for PCR amplification of the two distinct PCNA genes by Pfu polymerase (Stratagene) in the presence of TK0535-F (5′-CCGCATATGCCGTTCGAAGTTGTTTTTGACG) and TK0535-R (5′-CCGGGATCCTCAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGCTCCTCAACGCGCGGAGCG) primers used to amplify the TK0535 gene and TK0582-F (5′-CCGCATATGACTTTTGAGATTGTGTTTGATTC) and TK0582-R (5′-CCGGTCGACTCAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGTGAGCGACCCTCCTCGACTC) primers to amplify the TK0582 gene. The TK0535-F and TK0582-F primers contain the initiation codon ATG and NdeI restriction sites, whereas the TK0535-R and TK0582-R primers contain a sequence encoding six histidine residues followed by a stop codon and a BamHI (TK0535-R) or SalI (TK0582-R) restriction site. The PCR products were cloned into the the NdeI and BamHI (TK0535) or NdeI and SalI (TK0582) sites of the pET-21a vector (Novagene), resulting in pET-TK0535 and pET- TK0582, respectively.

The pET-TK0535 and pET-TK0582 plasmids were transformed into BL21 DE3 Rosetta cells (Invitrogen) and protein expression was induced at 37 °C by the addition of 0.5 mM IPTG and farther incubation for 3 h. The two PCNA proteins were purified by absorption and elution from a Ni column. The cell pellets of 4-L cultures were resuspended in loading buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 10% glycerol]. Following sonication, the extract was clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant was absorbed to 2-mL Ni column. The column was washed with loading buffer containing 50 mM imidazole. The PCNA proteins were eluted from the column in loading buffer containing 250 mM imidazole followed by dialysis in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, and 10% glycerol.

Elongation of a Singly Primed M13 DNA Template.

TK PolB catalyzed elongation of singly primed M13 single-stranded DNA was carried out in reaction mixtures (20 μL) containing 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 250 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM DTT, 0.01% BSA, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 2 mM ATP, 100 μM each of dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP, 20 μM [α-32P]dATP (1.2 × 104 cpm/pmol), 10 fmol of singly primed M13 mp18, and proteins as indicated in the legend of Fig. 5. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 20 min at 70 °C, stopped with 10 mM EDTA, and separated by electrophoresis through an alkaline agarose gel (1.1%) followed by autoradiography. For quantitation, aliquots (4 μL) of reaction mixtures were removed, and DNA synthesis measured by adsorption to DE81 paper followed by liquid scintillation counting.

Static Light Scattering.

The solution molecular mass of each PCNA protein was determined using size exclusion chromatography with in-line multiangle light scattering. A 1200 series HPLC system (Agilent Technologies) with a Shodex KW-802.5 or a Shodex KW-804 column (Showa Denko K.K.) was used for this purpose. The flow rate was 0.5 mL/ min, and the mobile phase was 0.01 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.5), 0.1 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.01% sodium azide. Light scattering was measured with a miniDawn Treos (Wyatt Technology); the protein concentration was measured with an Optilab rEX differential refractometer (Wyatt Technology).

Crystallization.

Both PCNAs were grown by vapor diffusion under the same conditions as PfuPCNA (D143A/D147A) (13). The well solution was 2.4–2.8 M ammonium sulfate and 100 mM sodium citrate, pH 5.2–5.8 with 5–10% 2,4-methyl pentanediol. The drops were formed by adding equal volumes of protein and well solution. Consequently, the drops were also 5% glycerol. TK0535 displayed a variety of morphologies; some gave only low resolution data. The data used for the structure were collected from a crystal that was a slender hexagonal rod, whereas TK0582 crystals were trapezoidal. The packing of the two PCNAs differed; TK0582 crystallized in space group C2221 with one trimer in the asymmetric unit, and TK0535 crystallized in space group P63 with a single polypeptide chain in the asymmetric unit.

Data Collection.

The diffraction data were collected using a Rigaku Micro Max 007 rotating anode generator and a Rigaku RAXIS IV++ detector (Rigaku/MSC). The crystals were cooled to 100 K with a cryocooler (Cryo Industries) and required no additional cryoprotectant. Diffraction data were collected and processed with CrystalClear/d*Trek (22). Statistics for the data collection are shown in Table 1 for both proteins.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| TK0535, 3LX1 | TK0582, 3LX2 | |

| Diffraction data | ||

| Space group | P63 | C2221 |

| Cell dimensions (a, b, c) (Å) | 89.23, 89.23, 62.67 | 120.48, 136.27, 123.97 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 29.21–2.00 | 29.63–2.40 |

| No. measured intensities | 107,393 | 103,299 |

| No. unique reflections | 19,294 | 36,454 |

| Mean redundancy | 5.57/5.43 | 2.83/2.72 |

| % completeness | 99.8/99.2 | 90.8/89.0 |

| Rmerge | 0.094/0.516 | 0.039/0.345 |

| Average I/sigI |

7.9/2.2 |

13.4/2.7 |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution limits (Å) | 29.21–2.00 | 29.86–2.40 |

| R factor (95% of the data) | 0.202/0.262 | 0.243/0.326 |

| Rfree (5% of the data) | 0.262/0.324 | 0.305/0.485 |

| rmsd bond lengths (Å) | 0.021 | 0.018 |

| rmsd bond angles (º) | 1.771 | 1.800 |

| Average B (main chain/side chain) (Å2) | 31.3/35.4 | 52.0/54.6 |

| Average B for water molecules (Å2) | 41.5 | 52.4 |

| No. polypeptide chains in asu | 1 | 3 |

| Residues missing electron density | A1, A248—249, His-tag | A1, A249–253; B1, B248–253;C1, C248–253; all 3 His-tags |

| No. water molecules | 82 | 68 |

| Ligands | 3 sulfate ions | 11 sulfate ions |

| Ramachandran* % favored/outliers | 98.0/0.4 | 93.9/1.0 |

*Calculated by MolProbity (27).

Structure Determination.

Both structures were determined by molecular replacement using the program PHASER (23) with PfuPCNA (12) (PDB ID code 1ge8) as the search model. The resulting models were adjusted using the graphics program COOT (24) and refined against the electron density using REFMAC5 (25, 26). The final refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1. The final structures were validated using the tools in COOT and the MolProbity (27) Web site (http://molprobity.biochem.duke.edu/). PYMOL (28) was used to generate the molecular figures.

Acknowledgments.

Certain commercial materials, instruments, and equipment are identified in this manuscript in order to specify the experimental procedure as completely as possible. In no case does such identification imply a recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology nor does it imply that the materials, instruments, or equipment identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant MCB-0815646 (to Z.K.) and by National Institutes of Health Grant GM034559 (to J.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 3LX1 and 3LX2 for TK0535 and TK0582, respectively).

References

- 1.Jeruzalmi D, O’Donnell M, Kuriyan J. Clamp loaders and sliding clamps. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Indiani C, O’Donnell M. The replication clamp-loading machine at work in the three domains of life. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:751–761. doi: 10.1038/nrm2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vivona JB, Kelman Z. The diverse spectrum of sliding clamp interacting proteins. FEBS Lett. 2003;546:167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00622-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spang A, et al. Distinct gene set in two different lineages of ammonia-oxidizing archaea supports the phylum Thaumarchaeota. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan M, Kelman LM, Kelman Z. The archaeal PCNA proteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39 doi: 10.1042/BST0390020. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atomi H, Fukui T, Kanai T, Morikawa M, Imanaka T. Description of Thermococcus kodakaraensis sp. nov., a well studied hyperthermophilic archaeon previously reported as Pyrococcus sp. KOD1. Archaea. 2004;1:263–267. doi: 10.1155/2004/204953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukui T, et al. Complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis KOD1 and comparison with Pyrococcus genomes. Genome Res. 2005;15:352–363. doi: 10.1101/gr.3003105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelman Z, O’Donnell M. Structural and functional similarities of prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA polymerase sliding clamps. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3613–3620. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.18.3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gulbis JM, Kelman Z, Hurwitz J, O’Donnell M, Kuriyan J. Structure of the C-terminal region of p21WAF1/CIP1 complexed with human PCNA. Cell. 1996;87:297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81347-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishna TS, Kong XP, Gary S, Burgers PM, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the eukaryotic DNA polymerase processivity factor PCNA. Cell. 1994;79:1233–1243. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsumiya S, Ishino Y, Morikawa K. Crystal structure of an archaeal DNA sliding clamp: Proliferating cell nuclear antigen from Pyrococcus furiosus. Protein Sci. 2001;10:17–23. doi: 10.1110/ps.36401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumiya S, Ishino S, Ishino Y, Morikawa K. Intermolecular ion pairs maintain the toroidal structure of Pyrococcus furiosus PCNA. Protein Sci. 2003;12:823–831. doi: 10.1110/ps.0234503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warbrick E. The puzzle of PCNA’s many partners. Bioessays. 2000;22:997–1006. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200011)22:11<997::AID-BIES6>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumiya S, Ishino S, Ishino Y, Morikawa K. Physical interaction between proliferating cell nuclear antigen and replication factor C from Pyrococcus furiosus. Genes Cells. 2002;7:911–922. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grabowski B, Kelman Z. Archaeal DNA replication: Eukaryal proteins in a bacterial context. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:487–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berthon J, Cortez D, Forterre P. Genomic context analysis in Archaea suggests previously unrecognized links between DNA replication and translation. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R71. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-4-r71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibbs E, et al. The influence of the proliferating cell nuclear antigen-interacting domain of p21CIP1 on DNA synthesis catalyzed by the human and Saccharomyces cerevisiae polymerase δ holoenzymes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2373–2381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishino Y, Tsurimoto T, Ishino S, Cann KO. Functional interactions of an archaeal sliding clamp with mammalian clamp loader and DNA polymerase δ. Genes Cells. 2001;6:699–706. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henneke G, et al. The PCNA from Thermococcus fumicolans functionally interacts with DNA polymerase δ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:600–606. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelman Z, Pietrokovski S, Hurwitz J. Isolation and characterization of a split B-type DNA polymerase from the archaeon Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28751–28761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pflugrath JW. The finer things in X-ray diffraction data collection. Acta Crystallogr D. 1999;55:1718–1725. doi: 10.1107/s090744499900935x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collaborataive Computational Project. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis IW, et al. MolProbity: All-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W375–383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeLano WL. San Carlos, CA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapados BR, et al. Structural basis for FEN-1 substrate specificity and PCNA-mediated activation in DNA replication and repair. Cell. 2004;116:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winter JA, Christofi P, Morroll S, Bunting KA. The crystal structure of Haloferax volcanii proliferating cell nuclear antigen reveals unique surface charge characteristics due to halophilic adaptation. BMC Struct Biol. 2009;9:55. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-9-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kontopidis G, et al. Structural and biochemical studies of human proliferating cell nuclear antigen complexes provide a rationale for cyclin association and inhibitor design. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1871–1876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406540102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meng EC, Pettersen EF, Couch GS, Huang CC, Ferrin TE. Tools for integrated sequence-structure analysis with UCSF Chimera. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:339. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]