Abstract

Linker for activation of T cells (LAT) plays a central role in T-cell activation by nucleating signaling complexes that are critical for the propagation of T-cell signals from the plasma membrane to the cellular interior. The role of phosphorylation and palmitoylation in LAT function has been well studied, but not much is known about other strategies by which the cell modulates LAT activity. We have focused on LAT ubiquitylation and have mapped the sites on which LAT is ubiquitylated. To elucidate the biological role of this process, we substituted LAT lysines with arginines. This resulted in a dramatic decrease in overall LAT ubiquitylation. Ubiquitylation-resistant mutants of LAT were internalized at rates comparable to wild-type LAT in a mechanism that required Cbl family proteins. However, these mutants displayed a defect in protein turnover rates. T-cell signaling was elevated in cells reconstituted with LAT mutants resistant to ubiquitylation, indicating that inhibition of LAT ubiquitylation enhances T-cell potency. These results support LAT ubiquitylation as a molecular checkpoint for attenuation of T-cell signaling.

Keywords: endocytosis, protein degradation, ubiquitin

Antigen activation of T cells leads to major cellular changes essential to the onset of a productive immune response. The earliest events occur upon T-cell antigen receptor (TCR) engagement and include activation of protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) and phosphorylation of multiple protein substrates. One critical PTK substrate is the integral membrane adapter molecule linker for activation of T cells (LAT), which upon phosphorylation, serves as a nucleation site for the formation of protein complexes composed of itself, other adapter molecules, and essential signaling enzymes activated at this site (1). A large number of studies have revealed that LAT-based complexes catalyze critical TCR-mediated signaling reactions and lead to the induction of multiple downstream pathways that direct almost all TCR-initiated cellular responses (2).

T-cell signaling must be tightly regulated, otherwise autoimmunity or a compromised immune response might ensue. Clearly, signal attenuation occurs at various stages during signal propagation. Proximally, the number and type of inhibitory coreceptors that are engaged on the T cell following TCR engagement greatly influence signal strength (3, 4). In addition, activation of the TCR also triggers mechanisms within the TCR signaling machinery that can decrease TCR-mediated signaling, including dephosphorylation of substrates by phosphatases, as well as phosphorylation on inhibitory residues by kinases (5). Finally, ubiquitylation and activation-induced endocytosis of proteins from the plasma membrane and subsequent degradation may eliminate activated signaling molecules (6, 7). Thus, tuning the excitation threshold of a T cell requires the coordinated regulation of multiple negative regulators.

A growing body of evidence supports the concept that clustering of the TCR and downstream signaling proteins is associated with and is important to effectively activate T cells. High-speed imaging approaches have shown that TCR-rich structures termed “microclusters” are formed within seconds of TCR engagement at the periphery of the T cell where it contacts the stimulatory surface (8–11). Studies from our laboratory using immobilized stimulatory antibodies demonstrated that TCR-rich microclusters contain signaling complexes that include interacting enzymes and adapters (12–14) and exclude tyrosine phosphatases such as CD45 (14). These adapters and effectors rapidly trigger critical biochemical events including tyrosine phosphorylation, Ca2+ flux, and diacylglycerol production, leading to the currently accepted theory that microclusters are sites of signal initiation in a T cell (15). A critical negative regulator of T-cell activation, the ubiquitin ligase c-Cbl, is also recruited into microclusters (6, 14), indicating that signal termination may also be occurring at the level of the ubiquitylation process.

In an effort to follow the intracellular fate of signaling complexes once they leave TCR-induced microclusters, we previously studied the trafficking of the adapters LAT and SLP-76, visualized as chimeric proteins tagged with YFP. Upon receptor activation, microclusters containing LAT and SLP-76 transiently associated with the TCR. Subsequently they translocated centripetally for a short distance and underwent endocytosis (6, 16). Expression of a dominant negative version of c-Cbl defective in E3 ligase activity prevented internalization and caused enhanced and prolonged signaling via static LAT clusters. Furthermore, we demonstrated that LAT was subject to ubiquitylation and expression of the Cbl mutant severely decreased LAT ubiquitylation (6). The physiological significance of this modification is the subject of this study.

We began by mapping the sites on which LAT is ubiquitylated. Inspection of the LAT amino acid sequence revealed lysine residues (K52 and K204 in human LAT), which might serve as sites for ubiquitylation. Substitution of LAT lysines with arginines resulted in a dramatic decrease in overall LAT ubiquitylation. Surprisingly, these ubiquitylation-deficient mutants of LAT were internalized at rates comparable to wild-type LAT in a mechanism that required Cbl family proteins. However, these mutants demonstrated a defect in protein turnover. Remarkably, cells bearing mutant LAT had a hyperresponsive phenotype and displayed elevated T-cell signaling. Although phosphorylation of LAT was not affected, elevated phosphorylation of downstream signaling proteins was observed. Thus, LAT ubiquitylation plays an important role in limiting downstream T-cell signals. Our observations also suggest that disruption of LAT ubiquitylation could be a means by which T-cell activity could be potentiated.

Results

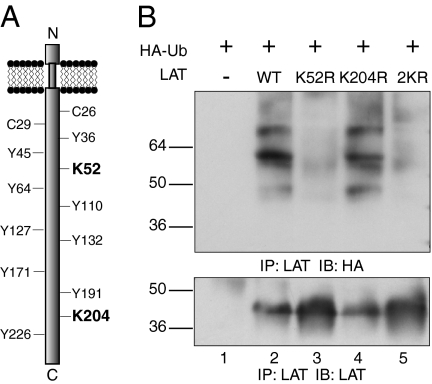

LAT Is Ubiquitylated on K52.

LAT contains a short extracellular domain, a single transmembrane-spanning region and a long intracellular region with no apparent intrinsic enzyme activity (Fig. 1A). The intracellular domain of LAT contains nine tyrosines of which five can be phosphorylated (17, 18), and two membrane proximal cysteine residues, which are subject to posttranslational palmitoylation (19). More recently, studies have shown that LAT is also subject to ubiquitylation (6, 20). Inspection of the LAT amino acid sequence reveals only two lysines (K52 and K204 in human LAT). To evaluate whether these lysine residues serve as ubiquitylation sites, they were mutated either individually or in combination, and the potential ubiquitylation of these LAT constructs was evaluated in COS-7 cells. Consistent with previously published studies (6, 20), immunoprecipitation of LAT resulted in the coprecipitation of ubiquitylated bands (Fig. 1B). Of note, the ubiquitylated bands represent modified LAT and not LAT-associated proteins because we have previously shown that they are detected in a denaturing immunoprecipitation (6). Strikingly, whereas the LAT K204R mutant displayed ubiquitylation levels similar to WT LAT (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 2 and 4), the LAT K52R mutant immunoprecipitates showed greatly decreased anti-HA reactivity (Fig. 1B, lane 3). Not surprisingly, the LAT 2KR mutant in which both LAT K52 and K204 were mutated also showed decreased ubiquitylation. The decreased HA reactivity is not due to a decrease in levels of expression because the LAT K52R and LAT 2KR mutants were consistently expressed at levels higher than the WT and K204R constructs (Fig. 1B, Lower). These data indicate that LAT is predominantly ubiquitylated on K52.

Fig. 1.

Lysine 52 is required for LAT ubiquitylation. (A) Schematic of human LAT protein. (B) COS-7 cells were transfected with HA epitope-tagged ubiquitin (HA-Ub) alone (lane 1) or HA-Ub and WT LAT (lane 2) or HA-Ub and LAT lysine mutants K52R, K204R, or 2KR as indicated. LAT was immunoprecipitated from whole cell lysates and the blots were immunoblotted for ubiquitin (with anti-HA) or LAT, as indicated. Molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons) appear to the Left of the panels. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

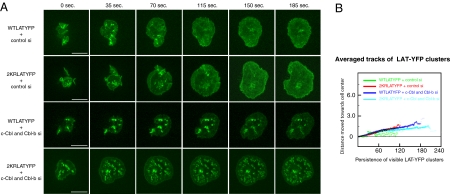

Ubiquitylation-Resistant LAT Microclusters Dissipate at Rates Similar to Wild-Type LAT, but Are Still Regulated by Cbl Proteins.

Seminal studies in yeast demonstrated that ubiquitin is required for internalization of membrane proteins (21). However, the situation in mammalian cells seems more complex because there are several examples in which receptor endocytosis proceeds in the absence of receptor ubiquitylation (22). To directly evaluate whether LAT ubiquitylation is required for LAT endocytosis, Jurkat E6.1 cells were transfected with either WT LAT-YFP or 2KR LAT-YFP. High-speed microscopic analysis of activated cells in real time revealed that both WT and 2KR LAT-YFP were recruited rapidly to signaling clusters. However, in both cases, clusters dissipated soon after formation (Fig. S1A, Upper, and Movies S1 and S2). Kymographic analyses show similar rates of loss (Fig. S1B). Analogous results were obtained in LAT-deficient JCam2.5 cells (Movies S3 and S4). These data indicate that ubiquitylation of LAT is not required for LAT internalization.

We have previously demonstrated that expression of 70Z/3 Cbl, an oncogenic, dominant negative version of c-Cbl with defective ubiquitin ligase activity (23), inhibits the movement and dissipation of LAT clusters (6). Because 70Z/3 Cbl may be exerting its effect through both c-Cbl and Cbl-b, siRNA-mediated depletion of c-Cbl and Cbl-b was used as an alternative, more specific approach to evaluate the role of Cbl proteins in regulation of LAT dynamics. When transfected together, these siRNAs caused significant depletion of both Cbl proteins (Fig. S2). As shown in Fig. 2A, in comparison with cells transfected with control siRNA (Fig. 2A, Upper panels, and Movies S5 and S6) Cbl depletion caused persistence of both WT and 2KR LAT clusters for extended periods of time (Fig. 2A, Lower panels, and Movies S7 and S8). Inhibition of WT and 2KR LAT movement was also observed in cells expressing 70Z/3 Cbl-CFP (Fig. S1A, Lower, and Movies S9 and S10). Kymographic analysis revealed persistence of clusters for both WT and 2KR LAT-YFP in the setting of either siRNA-mediated Cbl depletion or 70Z/3 Cbl expression, although expression of dominant negative Cbl caused LAT persistence for longer times probably due to residual Cbl expression in siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 2B and Fig. S1B). These experiments demonstrate that Cbl proteins regulate activated LAT dynamics regardless of whether LAT is ubiquitylated, likely because of the capacity of Cbl to target proteins involved in LAT internalization besides LAT itself.

Fig. 2.

Ubiquitylation-resistant LAT microclusters dissipate at rates similar to wild-type LAT and are regulated by Cbl proteins. E6.1 cells stably expressing WT LAT-YFP or 2KR LAT-YFP were plated onto stimulatory coverslips and visualized with a spinning-disk confocal system (Movies S5, S6, S7, and S8). Representative image sets from selected time points are shown. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (A, First and Second panels) Cells coexpressing control siRNA and WT-LAT-YFP (First) and 2KR LAT-YFP (Second). (Third and Fourth panels) Cells coexpressing siRNA targeting c-Cbl and Cbl-b and WT LAT-YFP (Third) and 2KR LAT-YFP (Fourth). (B) Kymograph with average traces demonstrating the movement of LAT-YFP clusters from seven cells.

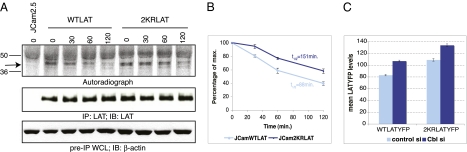

Ubiquitylation-Resistant LAT Protein Is More Stable and Has a Longer Half-Life.

Initially, ubiquitylation was described as the process that tags proteins for degradation (24). Consistent with a possible role of ubiquitylation in LAT degradation, 2KR LAT protein levels were higher than WT LAT protein levels even when equal amounts of WT and 2KR LAT DNA were transfected into cells (Fig. S3A). Evaluation of transcript abundance by quantitative RT-PCR revealed no significant differences between WT LAT-YFP and 2KR LAT-YFP transcripts (Fig. S3B), pointing to differences at the level of protein stability.

To test directly whether 2KR LAT is more stable and resistant to degradation than WT LAT, pulse-chase analysis was performed on LAT-deficient JCam2.5 cells engineered to express either WT or 2KR LAT. On the basis of these data, the intracellular half-life of WT LAT appears to be 88 min. In contrast, even at the 120-min time point, more than half of 2KR LAT persisted, demonstrating a significant delay in the degradation of the mutant protein (Fig. 3 A and B). Of note, the lysine mutations did not completely block steady state degradation, indicating that other mechanisms of protein degradation may exist for LAT or alternatively, that residual ubiquitylation of the lysine mutant drives degradation. Nonetheless, the 2KR mutation afforded LAT significant protection from degradation.

Fig. 3.

Ubiquitylation-resistant LAT is more stable. (A) JCam2.5 cells were stably transfected with WT or 2KR LAT. Cells were pulsed with 35S-labeled methionine and cysteine. Whole cell lysates were prepared at various time points after the initial pulse and subject to LAT immunoprecipitations (IPs). A total of 90% of the LAT IP was separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography (Top). The band corresponding to LAT is indicated with an arrow. A total of 10% of the LAT IP was analyzed by Western blot for total LAT levels (Middle). A fraction of the pre-IP whole cell lysate (WCL) was analyzed by Western blot for β-actin levels (Bottom). (B) Quantification of autoradiograph shown in A. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (C) E6.1 cells expressing WT or 2KR LAT-YFP were transiently transfected with control siRNA or siRNA targeting c-Cbl and Cbl-b as indicated. Forty-eight hours after transfection, mean LAT-YFP levels (± SEM) in YFP+ cells were measured by flow cytometry. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

The results in Fig. 2 demonstrate a role for Cbl proteins in regulation of LAT endocytosis in TCR-activated cells. To evaluate whether stimulation through the TCR or Cbl proteins regulates LAT protein lifetime, LAT half-life was measured under conditions of T-cell stimulation and c-Cbl and Cbl-b depletion. Whereas TCR stimulation did not dramatically alter LAT protein lifetime, the degradation rate of LAT was significantly delayed in cells depleted of c-Cbl and Cbl-b (Fig. S4). To further evaluate whether Cbl proteins can regulate LAT protein levels regardless of whether LAT is ubiquitylated, we analyzed expression levels of WT and 2KR LAT-YFP in cells in which both c-Cbl and Cbl-b expression were depleted by siRNA. LAT levels were evaluated by flow cytometry by gating on YFP-expressing cells. Depletion of Cbl protein expression increased both WT and 2KR LAT protein levels ∼1.3-fold compared with cells transfected with control siRNA (Fig. 3C). Thus, endogenous c-Cbl and Cbl-b function in regulating steady state LAT protein down-regulation for both WT and 2KR LAT. Taken together, the above results suggest that steady state LAT levels are regulated at multiple levels, one directly dependent on LAT ubiquitylation on lysines and another dependent on Cbl proteins. Strikingly, both WT and ubiquitin-resistant LAT showed a similar extent of dependency on the presence of Cbl. The regulation of LAT by Cbl proteins regardless of whether LAT is ubiquitylated points to a scenario in which Cbl regulates proteins controlling LAT levels besides LAT itself.

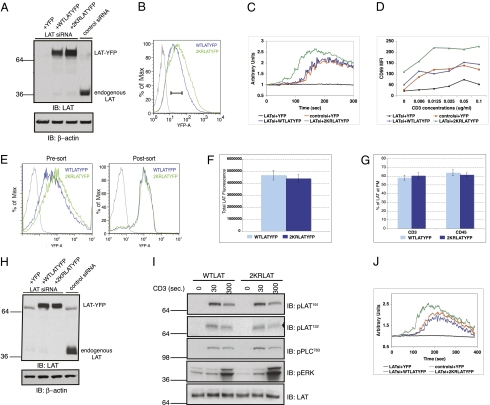

Ubiquitylation-Resistant LAT Causes Enhanced T-Cell Signaling.

Addition of ubiquitin moieties on signaling proteins may serve as a means to regulate the degree and duration of cell activation (25). To investigate whether increased stability of the LAT 2KR mutant in cells correlates with increased or prolonged signaling by this mutant, signaling assays were performed in cells expressing WT or 2KR LAT.

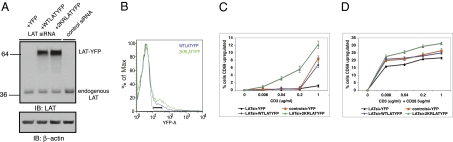

RNA-mediated interference was used to genetically silence endogenous LAT expression in Jurkat E6.1 cells. Simultaneously, YFP, WT LAT-YFP, or 2KR LAT-YFP was reexpressed in these cells. As shown in Fig. 4A, expression of siRNA targeting LAT dramatically reduced endogenous LAT expression. FACS analysis of the YFP-tagged proteins showed higher levels of 2KR LAT-YFP expression as expected (Fig. 4B). However, the YFP tag enabled us to gate on cells expressing equal amounts of YFP, corresponding to equivalent levels of LAT.

Fig. 4.

Ubiquitylation-resistant LAT causes enhanced T-cell signaling. (A–D) Jurkat E6.1 cells were transiently transfected with LAT targeting siRNA or control siRNA and control YFP plasmid, WT LAT-YFP, or 2KR LAT-YFP plasmids as indicated. (A) Whole cell lysates were prepared from the above-described transfected cells 48 h after transfection. The levels of endogenous LAT, transfected LAT-YFP (Upper) and β-actin (Lower) were assessed by immunoblotting. (B) Histogram showing WT LAT-YFP and 2KR LAT-YFP expression. For functional assays described in C and D, cells falling within the gate denoted by the black bar were analyzed. (C) Transfected cells were stimulated anti-CD3 and cytosolic Ca2+ influx was measured. (D) CD69 up-regulation was measured in transfected cells 16 h after anti-CD3 activation. Data are representative of a minimum of three independent experiments. (E–J) Cells transfected as above were sorted for equal levels of YFP expression. (E) Histogram showing WT LAT-YFP and 2KR LAT-YFP expression before and after cells were sorted. (F) Sorted cells were plated on coverslips and analyzed by confocal microscopy for total LAT levels or membrane LAT levels (G) on anti-CD3 and anti-CD45, respectively. (H) Whole cell lysates were prepared from the above-described sorted cells. The levels of endogenous LAT, transfected LAT-YFP (Upper) and β-actin (Lower) were assessed by immunoblotting. (I) Sorted cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 for indicated time points and whole cell lysates evaluated for phosphorylated and total protein levels as indicated. (J) Sorted cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 and cytosolic calcium Ca2+ flux was measured.

To test the consequence of disruption of LAT ubiquitylation for signaling events, TCR-induced Ca2+ influx was examined (Fig. 4C). Transfection of siRNA targeting endogenous LAT reduced Ca2+ flux to baseline, whereas control siRNA had no effect on the calcium response. Strikingly, LAT-depleted cells reconstituted with 2KR LAT-YFP showed increased cytosolic calcium flux compared with cells expressing comparable levels of WT LAT-YFP. Increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations upon TCR engagement controls various signaling pathways, including activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT). Therefore, LAT-expressing cells were subjected to NFAT luciferase assays. LAT-depleted cells reconstituted with 2KR LAT showed elevated NFAT activity at basal levels as well as all stimulation conditions tested, compared with cells reconstituted with its WT counterpart (Fig. S5). We also checked for other indicators of TCR signaling such as CD69 up-regulation. Basal and anti–CD3-induced CD69 up-regulation was enhanced at all doses of anti-CD3 antibody in cells reconstituted with 2KR LAT (Fig. 4D). Similar results were obtained in LAT-deficient JCam2.5 cells reconstituted with WT or 2KR LAT (Fig. S6). These data allow us to conclude that 2KR LAT causes enhanced T-cell activation compared with WT LAT.

In addition to the advantage afforded by 2KR LAT due to higher expression levels, the results discussed above indicate that even at equal levels of expression, the 2KR mutant causes enhanced T-cell signaling in Jurkat T cells. The elevated signaling could be due to increased surface levels of 2KR LAT or increased signaling downstream of LAT or both. To distinguish between these possibilities we sorted for cells expressing equal levels of WT and 2KR LAT-YFP (Fig. 4E). First, surface versus internal LAT expression was analyzed in sorted cells by confocal microscopy. Microscopic analysis revealed comparable levels of WT and 2KR LAT localized at the plasma membrane of either anti–CD3- or anti–CD45-stimulated cells (Fig. 4 F and G). Thus, higher surface levels of 2KR LAT do not appear to account for increased T-cell responsiveness in cells expressing the 2KR mutant. Next, phosphorylation of LAT and other downstream signaling molecules was examined. The levels of pLAT191 and pLAT132 were comparable in cells expressing WT and 2KR LAT (Fig. 4I). Further downstream, phosphorylation levels of PLC-γ1 and ERK were measured because these molecules play crucial roles in the coupling of TCR ligation to Ca2+ mobilization and CD69 up-regulation. Strikingly, phosphorylation of both PLC-γ1 and ERK were elevated in cells expressing 2KR LAT (Fig. 4I). Whereas phosphorylation of PLC-γ1 was slightly, but significantly elevated at early time points, ERK phosphorylation remained high even 5 min after CD3 stimulation. Equal levels of LAT expression in the two sets of sorted cells was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 4 H and I, Lower). We also demonstrated that Ca2+ flux was elevated in the sorted cells expressing 2KR LAT (Fig. 4J). These data indicate that the signaling advantage afforded by the 2KR mutant in activated T cells is not at the level of LAT phosphorylation, but downstream of LAT.

Ubiquitylation-Resistant LAT Causes Elevated Signaling in Primary Human T Cells.

To confirm that the effects of 2KR expression occurred in nontransformed cells, we performed experiments in primary human T cells. CD4+ cells were transfected with control siRNA or siRNA-targeting LAT and simultaneously with plasmids expressing YFP, WT LAT-YFP, or 2KR LAT-YFP as indicated. Similar to the Jurkat cell experiments, 2KR LAT expression levels were consistently higher compared with WT LAT (Fig. 5 A and B) after 24 h. As shown in Fig. 5A, a knockdown of 35% of endogenous LAT was achieved in these cells. Although not as efficient as LAT knockdown in Jurkat cells, the functional effects of 2KR LAT expression could be tested by gating on cells expressing equal levels of YFP (Fig. 5B). Transfected cells were incubated with various doses of anti-CD3 alone or anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies and evaluated for CD69 up-regulation. Consistent with observations made in Jurkat cells, we observed enhanced CD69 up-regulation in cells expressing 2KR LAT at all doses tested (Fig. 5 C and D). Strikingly, expression of 2KR LAT afforded relief from the requirement for CD28 costimulation and caused elevated CD69 up-regulation in cells stimulated with CD3 alone. Taken together, the data from Figs. 4 and 5 support the conclusion that ubiquitylation of LAT on lysines acts to coordinately down-regulate LAT-dependent T-cell signaling events.

Fig. 5.

Ubiquitylation-resistant LAT causes enhanced signaling in primary human CD4+ cells. Primary human CD4+ cells were transiently transfected with LAT targeting siRNA or control siRNA and control YFP plasmid, WT LAT-YFP, or 2KR LAT-YFP plasmids as indicated. (A) Whole cell lysates were prepared from the above-described transfected cells 24 h after transfection. The levels of endogenous LAT, transfected LAT-YFP (Upper) and β-actin (Lower) were assessed by immunoblotting. (B) Histogram showing WT LAT-YFP and 2KR LAT-YFP expression. For CD69 up-regulation assays described in C and D, cells falling within the gate denoted by the black bar were analyzed. (C) CD69 up-regulation was measured in gated cells 16 h after anti-CD3 alone or (D) anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 activation. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate a critical role for LAT ubiquitylation in maintaining normal T-cell signaling. This finding was demonstrated using a LAT mutant that exhibited severely reduced ubiquitylation and in different cell systems: LAT-deficient JCam2.5 Jurkat cells, Jurkat T cells in which LAT expression was suppressed, and primary human CD4+ cells. Consistently, cells bearing ubiquitin-deficient LAT displayed elevated basal and TCR-responsive signaling. In addition, LAT ubiquitylation was important for protein stability, and ubiquitylation-deficient mutants displayed an increase in protein lifetime. These findings indicate that ubiquitylation is a signal for steady-state LAT degradation and regulation of T-cell signaling.

In addition to being a signal for degradation, ubiquitin has emerged as a signal for controlling subcellular localization of targeted proteins (22). To our surprise, internalization rates of ubiquitylation-resistant LAT detected appear to be similar to those of WT LAT. Our results do not exclude the possibility that LAT ubiquitylation can function as an endocytic signal. Our results do indicate, however, that this cannot be the sole mechanism for initial internalization, and that other mechanisms can fully support the internalization process in the absence of the ubiquitylation of LAT. It is worth noting here that although ubiquitylation has been implicated as a sorting signal that targets activated molecules at the cell surface for endocytosis, studies using ubiquitin-defective mutants in several receptor systems revealed that receptor internalization was uncoupled from receptor ubiquitylation (22). These examples strongly suggest that ubiquitylation is not required for initial internalization of proteins at the plasma membrane. Instead ubiquitin is emerging as an intracellular sorting signal for molecules to be targeted for degradation instead of being recycled back to the cell membrane (26).

These findings have led us to revisit the role of the ubiquitin ligase c-Cbl in LAT endocytosis. In a previous study, we observed that expression of a Cbl RING domain mutant, which selectively lacks ubiquitin ligase activity, inhibited LAT endocytosis and ubiquitylation (6). Therefore, we hypothesized that Cbl regulated LAT endocytosis by modulating LAT ubiquitylation. However, internalization of LAT continues even under severely reduced ubiquitylation. Furthermore, Cbl depletion regulated LAT internalization and protein levels regardless of whether LAT was ubiquitylated. Thus, the effects of Cbl on LAT appear to be indirect and result from Cbl-mediated effects on proteins besides LAT. These proteins could potentially include other signaling molecules in the LAT-nucleated signaling complex, endocytic adapter proteins that mediate internalization or cytoskeletal proteins that regulate microcluster movement. Our results do not preclude the possibility that Cbl ubiquitylates LAT. Instead, taken together with essentially similar kinetics of internalization of WT and 2KR LAT, the Cbl depletion experiments indicate that ubiquitylation-resistant LAT is internalized using mechanisms normally used by WT LAT.

Despite essentially normal endocytosis, 2KR LAT caused enhanced T-cell signaling. What is the advantage afforded by ubiquitylation-resistant LAT? Certainly increased cellular levels of 2KR LAT contribute to the hyperresponsive phenotype. However, even at equal levels of expression and membrane density, 2KR LAT caused increased T-cell signaling. Comparable levels of phosphorylated LAT detected in WT and 2KR cells indicate that proximal PTK activation was not affected. However, increased phosphorylation of PLC-γ1 and ERK suggests key differences in the biochemical signaling pathways downstream of 2KR LAT. At least two models can account for elevated PLC-γ1 phosphorylation. In one model, the absence of bulky ubiquitin groups bound to LAT in the 2KR mutant allows for better access of downstream signaling molecules such as PLC-γ1 to LAT phosphotyrosines, allowing in increased levels of PLC-γ1 phosphorylation. Alternatively, lack of LAT ubiquitylation could subtly alter the intracellular fate of activated LAT by changes in location and/or duration of stay at a particular site and allow for enhanced signaling. The route of internalization may determine the fate of internalized signaling molecules. For example, receptors in the EGF, TGF-β/Nodal, and Wnt signaling pathways each have two alternative routes of internalization mediating signaling versus degradation (27–30). Careful analysis of the molecular composition and subcellular localization of LAT signaling complexes under conditions of impaired ubiquitylation will give insights into the mechanism of enhanced signaling afforded by 2KR LAT.

Strategies to improve T-cell potency have a direct impact on increasing the efficacy of T-cell based immunotherapies. The adoptive transfer of T cells appears to be a promising new treatment for various types of cancer (31, 32) and several strategies to increase the functional avidity of the TCR that target the binding of antigen at the cell surface have been proposed (33–36). An alternate approach would be to manipulate intracellular signaling pathways that normally act to attenuate T-cell signaling such as those mediated by Cbl-b and SHP-1 (37–39). The data presented here show that introduction of a LAT molecule resistant to ubiquitylation is another option by which to augment T-cell potency. Targeting a critical element of the TCR-coupled signaling pathway rather than molecules involved in multiple pathways and with potentially more complex targets could be advantageous.

In summary, we demonstrate that decreased ubiquitylation of LAT stabilizes LAT protein and improves signaling in T cells. Our data open up unique avenues to enhance T-cell activation and potentially generate a more effective T cell. This strategy may prove useful in efforts to direct T-cell responses against cancer cells or chronic viral infections. Future studies will address the molecular basis of the signaling advantage conferred by lysine mutant LAT and whether increased signaling observed in cells bearing LAT molecules resistant to ubiquitylation translates to increased T-cell functionality in an in vivo setting.

Materials and Methods

Culture and transfection of Jurkat cells and primary human T cells have been described before (12). COS-7 cell transfection, confocal microscopy, image processing to calculate lifetime of LAT clusters, stimulation of cells and immunoblotting were as previously described (6). siRNA-mediated depletion of LAT and Cbl, quantification of total and membrane LAT fluorescence in cells, functional assays, QPCR, pulse-chase, and all other protocols are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Bohmann for the HA-ubiquitin construct, B. Taylor for cell sorting, C. Regan and J. Pinski for technical help, and A. Weissman, S. Lipkowitz, and R. Kortum for critically reading the manuscript. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1007098108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Samelson LE. Signal transduction mediated by the T cell antigen receptor: The role of adapter proteins. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:371–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.092601.111357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balagopalan L, Sherman E, Samelson LE, Sommers CL. The LAT story: A tale of cooperativity, coordination and choreography. CSH Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a005512. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frauwirth KA, Thompson CB. Activation and inhibition of lymphocytes by costimulation. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:295–299. doi: 10.1172/JCI14941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leibson PJ. The regulation of lymphocyte activation by inhibitory receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acuto O, Di Bartolo V, Michel F. Tailoring T-cell receptor signals by proximal negative feedback mechanisms. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:699–712. doi: 10.1038/nri2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balagopalan L, et al. c-Cbl-mediated regulation of LAT-nucleated signaling complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8622–8636. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00467-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jang IK, Gu H. Negative regulation of TCR signaling and T-cell activation by selective protein degradation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:315–320. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campi G, Varma R, Dustin ML. Actin and agonist MHC-peptide complex-dependent T cell receptor microclusters as scaffolds for signaling. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1031–1036. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grakoui A, et al. The immunological synapse: A molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science. 1999;285:221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krummel MF, Davis MM. Dynamics of the immunological synapse: Finding, establishing and solidifying a connection. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:66–74. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(01)00299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yokosuka T, et al. Newly generated T cell receptor microclusters initiate and sustain T cell activation by recruitment of Zap70 and SLP-76. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1253–1262. doi: 10.1038/ni1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barda-Saad M, et al. Dynamic molecular interactions linking the T cell antigen receptor to the actin cytoskeleton. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:80–89. doi: 10.1038/ni1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braiman A, Barda-Saad M, Sommers CL, Samelson LE. Recruitment and activation of PLCgamma1 in T cells: A new insight into old domains. EMBO J. 2006;25:774–784. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunnell SC, et al. T cell receptor ligation induces the formation of dynamically regulated signaling assemblies. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:1263–1275. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seminario MC, Bunnell SC. Signal initiation in T-cell receptor microclusters. Immunol Rev. 2008;221:90–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barr VA, et al. T-cell antigen receptor-induced signaling complexes: Internalization via a cholesterol-dependent endocytic pathway. Traffic. 2006;7:1143–1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paz PE, et al. Mapping the Zap-70 phosphorylation sites on LAT (linker for activation of T cells) required for recruitment and activation of signalling proteins in T cells. Biochem J. 2001;356:461–471. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3560461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu M, Janssen E, Zhang W. Minimal requirement of tyrosine residues of linker for activation of T cells in TCR signaling and thymocyte development. J Immunol. 2003;170:325–333. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang W, Trible RP, Samelson LE. LAT palmitoylation: Its essential role in membrane microdomain targeting and tyrosine phosphorylation during T cell activation. Immunity. 1998;9:239–246. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brignatz C, Restouin A, Bonello G, Olive D, Collette Y. Evidences for ubiquitination and intracellular trafficking of LAT, the linker of activated T cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hicke L, Riezman H. Ubiquitination of a yeast plasma membrane receptor signals its ligand-stimulated endocytosis. Cell. 1996;84:277–287. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80982-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Acconcia F, Sigismund S, Polo S. Ubiquitin in trafficking: The network at work. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:1610–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andoniou CE, Thien CB, Langdon WY. Tumour induction by activated abl involves tyrosine phosphorylation of the product of the cbl oncogene. EMBO J. 1994;13:4515–4523. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06773.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haglund K, Dikic I. Ubiquitylation and cell signaling. EMBO J. 2005;24:3353–3359. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu Z, Hunter T. Degradation of activated protein kinases by ubiquitination. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:435–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.013008.092711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi SC, et al. Regulation of activin/nodal signaling by Rap2-directed receptor trafficking. Dev Cell. 2008;15:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Guglielmo GM, Le Roy C, Goodfellow AF, Wrana JL. Distinct endocytic pathways regulate TGF-beta receptor signalling and turnover. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:410–421. doi: 10.1038/ncb975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sigismund S, et al. Clathrin-mediated internalization is essential for sustained EGFR signaling but dispensable for degradation. Dev Cell. 2008;15:209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto H, Sakane H, Yamamoto H, Michiue T, Kikuchi A. Wnt3a and Dkk1 regulate distinct internalization pathways of LRP6 to tune the activation of beta-catenin signaling. Dev Cell. 2008;15:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.June CH. Adoptive T cell therapy for cancer in the clinic. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1466–1476. doi: 10.1172/JCI32446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kieback E, Uckert W. Enhanced T cell receptor gene therapy for cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:749–762. doi: 10.1517/14712591003689998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eshhar Z. Adoptive cancer immunotherapy using genetically engineered designer T-cells: First steps into the clinic. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2010;12:55–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holler PD, et al. In vitro evolution of a T cell receptor with high affinity for peptide/MHC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5387–5392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080078297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuball J, et al. Increasing functional avidity of TCR-redirected T cells by removing defined N-glycosylation sites in the TCR constant domain. J Exp Med. 2009;206:463–475. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Y, et al. Directed evolution of human T-cell receptors with picomolar affinities by phage display. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:349–354. doi: 10.1038/nbt1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zha Y, Gajewski TF. An adenoviral vector encoding dominant negative Cbl lowers the threshold for T cell activation in post-thymic T cells. Cell Immunol. 2007;247:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fawcett VC, Lorenz U. Localization of Src homology 2 domain-containing phosphatase 1 (SHP-1) to lipid rafts in T lymphocytes: Functional implications and a role for the SHP-1 carboxyl terminus. J Immunol. 2005;174:2849–2859. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmitt TM, Ragnarsson GB, Greenberg PD. T cell receptor gene therapy for cancer. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:1240–1248. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]