Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The link between diabetes and prostate cancer is rarely studied in Asians.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

The trend of age-standardized prostate cancer incidence in 1995–2006 in the Taiwanese general population was calculated. A random sample of 1,000,000 subjects covered by the National Health Insurance in 2005 was recruited. A total of 494,630 men for all ages and 204,741 men ≥40 years old and without prostate cancer at the beginning of 2003 were followed to the end of 2005. Cumulative incidence and risk ratio between diabetic and nondiabetic men were calculated. Logistic regression estimated the adjusted odds ratios for risk factors.

RESULTS

The trend of prostate cancer incidence increased significantly (P < 0.0001). The cumulative incidence markedly increased with age in either the diabetic or nondiabetic men. The respective risk ratio (95% CI) for all ages and age 40–64, 65–74, and ≥75 years was 5.83 (5.10–6.66), 2.09 (1.60–2.74), 1.35 (1.07–1.71), and 1.39 (1.12–1.71). In logistic regression for all ages or for age ≥40 years, age, diabetes, nephropathy, ischemic heart disease, dyslipidemia, living region, and occupation were significantly associated with increased risk, but medications including insulin and oral antidiabetic agents were not.

CONCLUSIONS

Prostate cancer incidence is increasing in Taiwan. A positive link between diabetes and prostate cancer is observed, which is more remarkable in the youngest age of 40–64 years. The association between prostate cancer and comorbidities commonly seen in diabetic patients suggests a more complicated scenario in the link between prostate cancer and diabetes at different disease stages.

The association between diabetes and prostate cancer has been inconsistently reported, even though two meta-analyses suggested that diabetic patients have a lower risk of prostate cancer of 9% (1) and 16% (2), respectively.

While the two meta-analyses were examined, many studies were case-control and only three focused on the follow-up of cohorts of diabetic patients (3–5). Among the three cohorts, the cases of prostate cancer were 9 (3), 498 (4), and 2,455 (5), respectively; and only the last (5) showed a significant 9% risk reduction in diabetic patients. Except for the first study being conducted in residents with diabetes in Rochester, Minnesota (3), the diabetic patients in the other two were from hospitalized patients in Denmark (4) and Sweden (5), respectively. The meta-analyses have limitations including a mixture of case-control and cohort designs, a mixture of incident and dead cases, a small number of prostate cancer in most studies, and different sources of subjects with potential selection bias. Although the contamination of type 1 diabetes is possibly minimal because >90% of overall patients have type 2 diabetes, residual confounding could not be excluded if the two types of diabetes are not differentiated.

Although some recent studies still suggested a lower risk of prostate cancer in diabetic patients including Caucasians (6,7), Iranians (8), Israelis (9), African Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Japanese Americans (6), the lower risk in African Americans and Native Hawaiians (6) was not significant. Two Japanese studies did not find any significant association (10,11). The Ohsaki Cohort Study suggested that diabetes was not predictive for total prostate cancer, but diabetic patients did show a higher risk of advanced cancer (11).

Because diabetic patients are prone to develop cancer involving pancreas, liver, breast, colorectum, bladder, and endometrium (12–15) and the protective effect of diabetes on prostate cancer requires confirmation, this study evaluated the possible link between diabetes and prostate cancer, and the potential risk factors, by using the reimbursement database of the National Health Insurance (NHI) in Taiwan.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Study population

According to the Ministry of Interior, >98.0% of the Taiwanese population in 2005 (22,770,383: 11,562,440 men and 11,207,943 women) were covered by the NHI (16). A random sample of 1,000,000 subjects covered by the NHI in 2005 was created by the National Health Research Institute. The reimbursement databases were available back to 1996. Identification number, sex, birth date, and diagnostic codes based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) were retrieved. Diabetes was coded 250.1–250.9, and prostate cancer was coded 185.

Because prostate cancer is rare in young men, we analyzed the data for all ages and for those aged ≥40 years in the following groups: 40–64, 65–74, and ≥75 years (case number of prostate cancer was too small for age <40 years). Figure 1 shows a flowchart for selecting cases for the study. After excluding women, type 1 diabetes (in Taiwan, patients with type 1 diabetes were issued a “Severe Morbidity Card” after certified diagnosis), living region unknown, and prostate cancer diagnosed before 2003, 494,630 men for all ages and 204,741 men ≥40 years old and without prostate cancer were followed from the beginning of 2003 to the end of 2005.

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the procedures in the calculation of 3-year cumulative incidence of prostate cancer from 2003 to 2005.

Statistical analyses

The trends of crude and age-standardized (to the 2000 World Health Organization [WHO] population) incidence of prostate cancer in 1995–2006 in the general population were first calculated from the Taiwan Cancer Registry database (17). Linear regression evaluated whether the trends changed significantly, where the incidence was the dependent and the calendar year the independent variable.

The age-specific cumulative incidences from 2003 to 2005 in diabetic and nondiabetic men were calculated for all ages and age 40–64, 65–74, and ≥75 years. The numerator was the number of patients with a first diagnosis of prostate cancer within 2003–2005; and the denominator was the number of insurants in that specific age. The risk ratio between diabetic and nondiabetic men was calculated, and the 95% CI was estimated by Taylor series approximation (18). To minimize the possibility that diabetes might be caused by prostate cancer during a different period, several lag time sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding patients with diabetes duration of <1, <3, and <5 years.

In Taiwan, the National Health Research Institute recommends yearly screening of prostate cancer by digital rectal examination and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) determination for men aged ≥50 years or ≥45 years for those with a family history. The PSA cutoff is set at 4.0 ng/mL. If either examination is abnormal, prostate biopsy guided by transrectal ultrasonography is recommended. The cancer detection rate under this guideline was much lower in Taiwan (0.96–1.3%) than in the Western countries (3–5%); and population-based PSA screening program is not considered as cost effective (19). Therefore PSA test is not paid by the NHI when used for screening purpose in clinical practice. To evaluate whether the use of PSA test differed between those with and without diabetes, χ2 test compared the frequency of PSA test in 2003–2005 by diabetes status among men for all ages and for age ≥40 years.

Logistic regression calculated the adjusted odds ratios (ORs). Prostate cancer was the dependent variable, and the independent variables included age (<40, 40–64, 65–74, and ≥75 years), diabetes duration (nondiabetes, <1, 1–3, 3–5, and ≥5 years), comorbidities, medications, living region, and occupation. The comorbidities (ICD-9-CM codes) included hypertension (401–405), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (490–496, a surrogate for smoking), stroke (430–438), nephropathy (580–589), ischemic heart disease (410–414), peripheral arterial disease (250.7, 785.4, 443.81, 440–448), eye disease (250.5, 362.0, 369, 366.41, 365.44), obesity (278), and dyslipidemia (272.0–272.4). Medications included statin, fibrate, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and/or angiotensin receptor blocker, calcium channel blocker, sulfonylurea, metformin, insulin, acarbose, pioglitazone, and rosiglitazone. Comorbidities and medications were counted only as they appeared before 2003 to assure temporal correctness of cause and effect (prostate cancer). The NHI insurants were classified according to occupation, and this served as a surrogate for socioeconomic status. The living region served as a surrogate for geographical distribution of some environmental exposure. Occupation was categorized as follows: I: civil servants, teachers, employees of governmental or private business, professionals, and technicians; II: people without particular employers, self-employed, or seamen; III: farmers or fishermen; and IV: low-income families supported by social welfare or veterans. Living region was categorized as Taipei, Northern, Central, Southern, and Kao-Ping and Eastern. The regressions were performed for all ages and for age ≥40 years, separately. Because earlier analyses showed a significantly higher frequency of PSA test in the diabetic patients, additional logistic models were created by including PSA test as an additional independent variable to control for its potential confounding effect.

Analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data were expressed as mean (SD) for continuous variables or number (%) for categorical variables. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

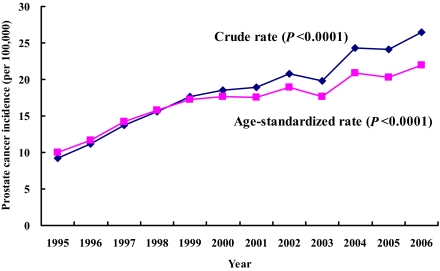

Figure 2 shows the crude and age-standardized incidence trends in the general population. Both are increasing significantly (P < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Trends of prostate cancer incidence in the general population of Taiwan from 1995 to 2006 (♦, crude rate;  , age-standardized rate using the 2000 WHO population as referent). (A high-quality color representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

, age-standardized rate using the 2000 WHO population as referent). (A high-quality color representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

Table 1 shows the 3-year cumulative incidences and the risk ratios between the diabetic and nondiabetic men in different ages. The cumulative incidence markedly increased with age in either the diabetic or nondiabetic men. Risk ratio analysis showed that diabetic patients had a higher risk than nondiabetic men in all age groups. However, divergent associations with regard to age were noted: those in the youngest age of 40–64 years had the highest risk ratio, followed by those in the oldest of ≥75 years, and those aged 65–74 years had the lowest risk ratio.

Table 1.

Rates (per 100,000) and risk ratios of 3-year cumulative incidence of prostate cancer from 2003 to 2005 in diabetic and nondiabetic men by age

| Three-year cumulative incidence by age (years) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All ages | 40–64 | 65–74 | ≥75 | |

| Diabetes of any duration | ||||

| Diabetic men | ||||

| n of prostate cancer | 362 | 75 | 120 | 166 |

| n of diabetic men | 52,133 | 26,476 | 9,959 | 8,715 |

| Rate in diabetic men | 694.38 | 283.28 | 1,204.94 | 1,904.76 |

| Nondiabetic men | ||||

| n of prostate cancer | 527 | 174 | 159 | 181 |

| n of nondiabetic men | 442,509 | 128,587 | 17,841 | 13,168 |

| Rate in nondiabetic men | 119.09 | 135.32 | 891.21 | 1,374.54 |

| Risk ratio | 5.83 (5.10–6.66) | 2.09 (1.60–2.74) | 1.35 (1.07–1.71) | 1.39 (1.12–1.71) |

| Excluding diabetes diagnosed <1 year | ||||

| Diabetic men | ||||

| n of prostate cancer | 342 | 67 | 112 | 162 |

| n of diabetic men | 47,789 | 24,000 | 9,342 | 8,242 |

| Rate in diabetic men | 715.65 | 279.17 | 1,198.89 | 1,965.54 |

| Nondiabetic men | ||||

| n of prostate cancer | 527 | 174 | 159 | 181 |

| n of nondiabetic men | 442,509 | 128,587 | 17,841 | 13,168 |

| Rate in nondiabetic men | 119.09 | 135.32 | 891.21 | 1,374.54 |

| Risk ratio | 6.01 (5.25–6.88) | 2.06 (1.56–2.73) | 1.35 (1.06–1.71) | 1.43 (1.16–1.76) |

| Excluding diabetes diagnosed <3 years | ||||

| Diabetic men | ||||

| n of prostate cancer | 292 | 52 | 96 | 144 |

| n of diabetic men | 39,014 | 19,064 | 8,005 | 7,238 |

| Rate in diabetic men | 748.45 | 272.77 | 1,199.25 | 1,989.50 |

| Nondiabetic men | ||||

| n of prostate cancer | 527 | 174 | 159 | 181 |

| n of nondiabetic men | 442,509 | 128,587 | 17,841 | 13,168 |

| Rate in nondiabetic men | 119.09 | 135.32 | 891.21 | 1,374.54 |

| Risk ratio | 6.28 (5.45–7.25) | 2.02 (1.48–2.75) | 1.35 (1.05–1.73) | 1.45 (1.17–1.80) |

| Excluding diabetes diagnosed <5 years | ||||

| Diabetic men | ||||

| n of prostate cancer | 233 | 40 | 75 | 118 |

| n of diabetic men | 29,868 | 14,100 | 6,493 | 6,052 |

| Rate in diabetic men | 780.10 | 283.69 | 1,155.09 | 1,949.77 |

| Nondiabetic men | ||||

| n of prostate cancer | 527 | 174 | 159 | 181 |

| n of nondiabetic men | 442,509 | 128,587 | 17,841 | 13,168 |

| Rate in nondiabetic men | 119.09 | 135.32 | 891.21 | 1,374.54 |

| Risk ratio | 6.55 (5.62–7.64) | 2.10 (1.49–2.95) | 1.30 (0.99–1.70) | 1.42 (1.13–1.79) |

Diabetic patients did show a higher frequency in the use of PSA test in either the analysis for all ages or for age ≥40 years (Table 2).

Table 2.

Examination of PSA in 2003–2005 by status of diabetes for all ages and age ≥40 years in Taiwanese men

| Examination of PSA | Diabetes |

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No |

Yes |

||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| All ages | |||||

| No | 441,829 | 99.85 | 51,662 | 99.10 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 680 | 0.15 | 471 | 0.90 | |

| Age ≥40 years | |||||

| No | 158,928 | 99.58 | 44,681 | 98.96 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 668 | 0.42 | 469 | 1.04 | |

Table 3 shows the results of the logistic regressions. The results were similar in models without (model I) or with (model II) PSA as an additional independent variable. In model II only the ORs for the different subgroups of diabetes duration and PSA test are shown. Age was a remarkable risk factor, and diabetes duration showed a nonlinear increase in the risk. Nephropathy, ischemic heart disease, dyslipidemia, living region, and occupation were significant, whereas chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was borderline significant. None of the medications was significant.

Table 3.

Mutually adjusted ORs for prostate cancer derived from cumulative incident cases from 2003 to 2005

| Variables | All ages |

Age ≥40 years |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Model I | ||||

| Age, years | ||||

| <40 | Referent | |||

| 40–64 | 30.25 (17.62–51.91) | <0.0001 | Referent | |

| 65–74 | 164.57 (95.10–284.81) | <0.0001 | 5.44 (4.50–6.58) | <0.0001 |

| ≥75 | 239.01 (137.40–415.76) | <0.0001 | 7.89 (6.45–9.67) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes duration, years vs. nondiabetics | ||||

| <1 | 1.25 (0.79–1.96) | 0.3386 | 1.25 (0.80–1.96) | 0.3352 |

| 1–3 | 1.45 (1.08–1.95) | 0.0130 | 1.43 (1.06–1.92) | 0.0198 |

| 3–5 | 1.40 (1.05–1.86) | 0.0224 | 1.40 (1.05–1.87) | 0.0218 |

| ≥5 | 1.30 (1.06–1.60) | 0.0129 | 1.30 (1.06–1.60) | 0.0130 |

| Hypertension, yes vs. no | 1.12 (0.94–1.33) | 0.2037 | 1.12 (0.94–1.34) | 0.1922 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, yes vs. no | 1.15 (0.99–1.33) | 0.0657 | 1.16 (1.00–1.34) | 0.0535 |

| Stroke, yes vs. no | 0.98 (0.81–1.17) | 0.8004 | 0.98 (0.82–1.17) | 0.8057 |

| Nephropathy, yes vs. no | 1.27 (1.04–1.53) | 0.0172 | 1.27 (1.05–1.54) | 0.0161 |

| Ischemic heart disease, yes vs. no | 1.29 (1.09–1.52) | 0.0026 | 1.28 (1.08–1.51) | 0.0035 |

| Peripheral arterial disease, yes vs. no | 0.95 (0.74–1.21) | 0.6606 | 0.95 (0.74–1.21) | 0.6595 |

| Eye disease, yes vs. no | 1.21 (0.84–1.75) | 0.3161 | 1.21 (0.84–1.75) | 0.3123 |

| Obesity, yes vs. no | 0.80 (0.26–2.51) | 0.7037 | 0.81 (0.26–2.55) | 0.7228 |

| Dyslipidemia, yes vs. no | 1.42 (1.19–1.70) | 0.0001 | 1.41 (1.18–1.69) | 0.0002 |

| Statin, yes vs. no | 1.14 (0.90–1.46) | 0.2760 | 1.15 (0.90–1.47) | 0.2567 |

| Fibrate, yes vs. no | 0.93 (0.73–1.19) | 0.5782 | 0.94 (0.74–1.19) | 0.5897 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker, yes vs. no | 1.07 (0.86–1.34) | 0.5422 | 1.07 (0.86–1.34) | 0.5427 |

| Calcium channel blocker, yes vs. no | 0.91 (0.72–1.15) | 0.4299 | 0.91 (0.72–1.15) | 0.4274 |

| Sulfonylurea, yes vs. no | 1.07 (0.78–1.46) | 0.6873 | 1.07 (0.78–1.46) | 0.6903 |

| Metformin, yes vs. no | 0.79 (0.56–1.11) | 0.1796 | 0.79 (0.56–1.11) | 0.1781 |

| Insulin, yes vs. no | 0.52 (0.21–1.27) | 0.1501 | 0.51 (0.21–1.27) | 0.1481 |

| Acarbose, yes vs. no | 1.00 (0.49–2.02) | 0.9901 | 1.00 (0.49–2.02) | 0.9905 |

| Pioglitazone, yes vs. no | 0.77 (0.10–5.75) | 0.7955 | 0.77 (0.10–5.77) | 0.7979 |

| Rosiglitazone, yes vs. no | 0.88 (0.43–1.80) | 0.7180 | 0.88 (0.43–1.80) | 0.7206 |

| Living region | ||||

| Northern vs. Taipei | 0.83 (0.68–1.01) | 0.0604 | 0.84 (0.69–1.02) | 0.0756 |

| Central vs. Taipei | 0.66 (0.54–0.81) | <0.0001 | 0.68 (0.56–0.83) | 0.0002 |

| Southern vs. Taipei | 0.44 (0.35–0.57) | <0.0001 | 0.46 (0.36–0.58) | <0.0001 |

| Kao-Ping and Eastern vs. Taipei | 0.48 (0.39–0.60) | <0.0001 | 0.49 (0.40–0.61) | <0.0001 |

| Occupation | ||||

| II vs. I | 0.67 (0.52–0.86) | 0.0015 | 0.68 (0.53–0.88) | 0.0028 |

| III vs. I | 0.78 (0.64–0.95) | 0.0126 | 0.77 (0.63–0.94) | 0.0116 |

| IV vs. I | 0.83 (0.70–0.99) | 0.0370 | 0.84 (0.71–0.99) | 0.0475 |

| Model II* | ||||

| Diabetes duration, years vs. nondiabetics | ||||

| <1 | 1.207 (0.766–1.904) | 0.4175 | 1.209 (0.767–1.907) | 0.4139 |

| 1–3 | 1.410 (1.046–1.900) | 0.0242 | 1.381 (1.022–1.866) | 0.0357 |

| 3–5 | 1.387 (1.036–1.857) | 0.0278 | 1.389 (1.038–1.859) | 0.0270 |

| ≥5 | 1.266 (1.028–1.559) | 0.0267 | 1.266 (1.027–1.559) | 0.0269 |

| PSA test, yes vs. no | 13.490 (10.899–16.697) | <0.0001 | 13.374 (10.799–16.563) | <0.0001 |

Refer to research design and methods for the categories of occupation.

*Model II: additionally adjusted for PSA test; only the ORs for diabetes duration and PSA test are shown.

CONCLUSIONS

The trends of prostate cancer were increasing significantly in 1995–2006 (Fig. 2), and diabetes was associated with an increased risk at any duration (Tables 1 and 3), with the highest risk ratio observed in the youngest age of 40–64 years (Table 1).

Although some recent studies still favored a protective effect of diabetes in Caucasians (6,7), a recent population-based case-control study in the US concluded that diabetes was not associated with prostate cancer (OR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.76–1.27) and that the protective effect of diabetes might be because of a confounding of a mixture with type 1 diabetes (20). In the current study, patients with type 1 diabetes were excluded and its confounding is minimal.

Diabetes was unlikely caused by prostate cancer, because the association was consistent in different analyses (Table 1). Diabetes diagnosed 5 years before prostate cancer can hardly be a consequence of the carcinogenic process. Another possibility for an increased incidence in the diabetic patients is because of screening bias (Table 2). However, our analysis did not support such a possibility because the conclusions remained the same when PSA test was also included in the logistic analyses (model II of Table 3).

Heterogeneity may exist in the association between diabetes and prostate cancer. Some suggested that recent-onset diabetes may increase, but long-standing diabetes might reduce the risk (21). In the current study, although prostate cancer risk increased with increasing diabetes duration in unadjusted models (data not shown), the adjusted models showed that the highest risk was observed at diabetes duration of 1–3 years and then declined gradually (Table 3). Recently serum creatinine is shown to be significantly predictive for prostate cancer risk (22). Our finding of a significantly higher risk of 27% in patients with nephropathy (Table 3) confirmed such an observation. Some suggested that patients with more severe diabetes might have lower level of PSA and lower risk of prostate cancer (23). However, the current study showing a higher risk of prostate cancer associated with nephropathy, ischemic heart disease, and dyslipidemia (Table 3) argued against a simple scenario. With increasing duration and severity of diabetes, chronic complications may set in and interfere with the association between diabetes and prostate cancer. Some suggested that diabetes might only convey a higher risk of more advanced prostate cancer (11,24). However, we did not have sufficient information for analysis.

It is interesting to observe an effect modification by age with the highest risk ratio observed at the youngest age of 40–64 years (Table 1). One explanation is that a higher mortality from other causes in the older diabetic patients before the development of prostate cancer may obscure the relationship, as opposed to the youngest age group who might have been exposed to inflammatory and carcinogenic effects of diabetes for a longer period of time. Such a relationship simply might not have been captured by case-control designs.

Some commonly used medications did not affect the risk (Table 3). However, geographical distribution and socioeconomic status, as indicated by living region and occupation, respectively, did significantly impact the risk (Table 3). People living in metropolitan Taipei region had the highest risk, and the risk seemed to decline gradually with lesser urbanization as shown from the ORs, much deviating from unity from Northern to Central, Southern, and Kao-Ping and Eastern region (Table 3). People with a higher socioeconomic status as indicated by occupation I also suffered from a higher risk (Table 3). The reasons for such discrepancy with regard to geographical distribution and socioeconomic status await further exploration.

This study has several strengths. It is population based with a large nationally representative sample. The database included outpatients and inpatients, and we caught the diagnoses from both sources. Cancer is considered as a severe morbidity by the NHI, and most medical copayments can be waived. Therefore the detection rate would not tend to differ among different social classes. The use of medical record also reduced the potential bias related to self-reporting.

Limitations included a lack of actual measurement of confounders such as obesity, smoking, alcohol drinking, family history, lifestyle, diet, hormones, and genetic parameters. In addition, we did not have biochemical data for evaluating their impact. Finally, the follow-up interval is probably too short to plausibly account for the likely induction time needed between the onset of diabetes and the biological changes leading to prostate cancer.

In summary, this study shows an increasing trend of prostate cancer in Taiwan and a link between diabetes and prostate cancer, which is more remarkable in the age of 40–64 years. Therefore, the observation that diabetes confers a lower risk of prostate cancer might not be universal. Insulin or other oral antidiabetic agents are not, but nephropathy, ischemic heart disease, and dyslipidemia are significantly associated with prostate cancer. The association between prostate cancer and these comorbidities suggests a more complicated scenario in the link between prostate cancer and diabetes at different disease stages. Given that the population is aging, the incidence of prostate cancer is increasing, and the incidence of type 2 diabetes is also increasing (25). The impact of prostate cancer on the population should warrant public health attention.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Genotyping Center of National Research Program for Genomic Medicine, National Science Council; the Department of Health (grants DOH89-TD-1035, DOH97-TD-D-113-97009); and the National Science Council (grants NSC-86-2314-B-002-326, NSC-87-2314-B-002-245, NSC-88-2621-B-002-030, NSC-89-2320-B002-125, NSC-90-2320-B-002-197, NSC-92-2320-B-002-156, NSC-93-2320-B-002-071, NSC-94-2314-B-002-142, NSC-95-2314-B-002-311, NSC-96-2314-B-002-061-MY2).

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

C.-H.T. researched data and wrote the article.

The author thanks the National Genotyping Center of National Research Program for Genomic Medicine, National Science Council; the Department of Health; and the National Science Council for their support on epidemiologic studies of diabetes and arsenic-related health hazards.

References

- 1.Bonovas S, Filioussi K, Tsantes A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2004;47:1071–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasper JS, Giovannucci E. A meta-analysis of diabetes mellitus and the risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15:2056–2062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ragozzino M, Melton LJ, 3rd, Chu CP, Palumbo PJ. Subsequent cancer risk in the incidence cohort of Rochester, Minnesota, residents with diabetes mellitus. J Chronic Dis 1982;35:13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wideroff L, Gridley G, Mellemkjaer L, et al. Cancer incidence in a population-based cohort of patients hospitalized with diabetes mellitus in Denmark. J Natl Cancer Inst 1997;89:1360–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiderpass E, Ye W, Vainio H, Kaaks R, Adami HO. Reduced risk of prostate cancer among patients with diabetes mellitus. Int J Cancer 2002;102:258–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waters KM, Henderson BE, Stram DO, Wan P, Kolonel LN, Haiman CA. Association of diabetes with prostate cancer risk in the multiethnic cohort. Am J Epidemiol 2009;169:937–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasper JS, Liu Y, Giovannucci E. Diabetes mellitus and risk of prostate cancer in the health professionals follow-up study. Int J Cancer 2009;124:1398–1403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baradaran N, Ahmadi H, Salem S, et al. The protective effect of diabetes mellitus against prostate cancer: role of sex hormones. Prostate 2009;69:1744–1750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chodick G, Heymann AD, Rosenmann L, et al. Diabetes and risk of incident cancer: a large population-based cohort study in Israel. Cancer Causes Control 2010;21:879–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishina T, Watanabe H, Araki H, Nakao M. Epidemiological study of prostatic cancer by matched-pair analysis. Prostate 1985;6:423–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Q, Kuriyama S, Kakizaki M, et al. History of diabetes mellitus and the risk of prostate cancer: the Ohsaki Cohort Study. Cancer Causes Control 2010;21:1025–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tseng CH, Chong CK, Tai TY. Secular trend for mortality from breast cancer and the association between diabetes and breast cancer in Taiwan between 1995 and 2006. Diabetologia 2009;52:240–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tseng CH, Chong CK, Tseng CP, Chan TT. Age-related risk of mortality from bladder cancer in diabetic patients: a 12-year follow-up of a national cohort in Taiwan. Ann Med 2009;41:371–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vigneri P, Frasca F, Sciacca L, Pandini G, Vigneri R. Diabetes and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2009;16:1103–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, et al. Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. Diabetes Care 2010;33:1674–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health, Taiwan. Statistics of national health insurance in 2005: table 6. Beneficiaries by gender and sex [article online]. Available from http://www.doh.gov.tw/CHT2006/DM/DM2_2.aspx?now_fod_list_no=10383&class_no=440&level_no=4 Accessed 8 August 2009

- 17.Taiwan Cancer Registry. Secular trends of incidence of prostate cancer in Taiwan from 1979 to 2007 [article online]. Available from http://tcr.cph.ntu.edu.tw/uploadimages/Year_Male%20genital.xls Accessed 20 July 2010

- 18.Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Morgenstern H. Epidemiologic Research: Principles and Quantitative Methods. New York, John Wiley and Sons, 1982, p. 298–299 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu TT. Should a prostate biopsy be advised for men with serum prostate-specific antigen levels of 2.5-4.0 ng/ml? JTUA 2007;18:135–138 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pierce BL, Plymate S, Ostrander EA, Stanford JL. Diabetes mellitus and prostate cancer risk. Prostate 2008;68:1126–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darbinian JA, Ferrara AM, Van Den Eeden SK, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Fireman B, Habel LA. Glycemic status and risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17:628–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinstein SJ, Mackrain K, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Selhub J, Virtamo J, Albanes D. Serum creatinine and prostate cancer risk in a prospective study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:2643–2649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Müller H, Raum E, Rothenbacher D, Stegmaier C, Brenner H. Association of diabetes and body mass index with levels of prostate-specific antigen: implications for correction of prostate-specific antigen cutoff values? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:1350–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leitzmann MF, Ahn J, Albanes D, et al. Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Trial Project Team Diabetes mellitus and prostate cancer risk in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. Cancer Causes Control 2008;19:1267–1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tseng CH, Tseng CP, Chong CK, et al. Increasing incidence of diagnosed type 2 diabetes in Taiwan: analysis of data from a national cohort. Diabetologia 2006;49:1755–1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]