Abstract

Newborn screening (NBS) is a complex process that has high-stakes health implications and requires rapid and effective communication between many people and organizations. Currently, each NBS laboratory has its own method of reporting results to state programs, hospitals and individual providers, with wide variation in content and format. Pediatric care providers receive reports by mail, email, fax or telephone, depending on whether the results are normal or abnormal. This process is slow and prone to errors, which can lead to delays in treatment. Multiple agencies worked together to create national guidance for reporting newborn screening results with HL7 messages that contain a prescribed set of LOINC and SNOMED CT codes, report quantitative test results, and use standardized units of measure. Several states are already implementing this guidance. If the guidance is used nationally, office EHRs could capture NBS results more efficiently, and regional and national registries could better analyze aggregate results to facilitate improvements in NBS and further research for these rare conditions.

Introduction

The goal of NBS is to identify apparently healthy infants with medical conditions that can be treated before causing significant morbidity or mortality. NBS includes both dried blood spot (DBS) and hearing tests. Most NBS conditions are rare and comparing NBS data across states is necessary to optimize protocols and assess outcomes. Until this project began, there was no national standard for NBS reporting, and therefore no way to efficiently transmit data to pediatric care providers, or to reliably compare or pool data across states. In this report we describe a standard way to deliver newborn screening results in a Health Level Seven (HL7) message.

Background

In the United States, NBS programs are operated by fifty states plus the District of Columbia, certain U.S. territories and the military. Most of the programs test for 29 of the 30‡ core conditions included in the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel of the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children.1 Many also screen for various additional conditions. Most programs recommend DBS screening at 24–48 hours after birth, and hearing screening at least 24 hours after birth but before hospital discharge. Nine states require, and others recommend, a repeat DBS screen at one to two weeks of age such that about 25% of newborns receive two screens. The newborn’s blood is collected by heel stick on filter paper attached to a collection card that includes questions (“card variables”) about the newborn and mother. The DBS is used to screen for metabolic, hematologic, endocrine and other abnormalities. Congenital hearing loss is screened by physiologic measures.

Programs not only differ in the conditions screened, but also in how results are reported. One major problem is that each program uses its own local codes to identify tests and results. In addition, some report only qualitative values, while others give quantitative results or a combination. For example, abnormal results for congenital hypothyroidism (CH) are reported in many different ways, including “TSH(borderline),” “T4 low/TSH slightly elevated” and “TSH 137 mIU/mL, reference range <20 mIU/mL.” Normal hemoglobin results can be reported as “normal” or “FA.” Quantitative results can be reported as numbers, ranges, or percentiles. Some programs report results for individual conditions or the individual test measure, while others group results based on disorder categories, again with differences in grouping. Given all of this variability, as practices begin implementing electronic health records (EHRs), it is difficult for system developers to capture NBS results efficiently, and for regional or national registries to compare data across programs to analyze NBS information.

Most programs do not yet report NBS results electronically. They usually use the telephone to report positive DBS results to pediatric care providers due to the urgent need for follow-up and treatment, and postal mail to send normal NBS reports to the birthing facility or pediatric care provider designated when the baby is screened; a few use fax or email. However, the provider who sees the baby in the hospital is often not the one who treats the baby after discharge. Some states do not send negative results as timely as they could, which can cause confusion and delay. In one survey of pediatricians, 26% reported they were not routinely notified of screen-negative results. When asked hypothetically if they would actively track down NBS results for a 2-week-old infant with a normal exam, 28% reported they would not either because they assumed “no news is good news,” the state does a good job, or a combination of “the infant is healthy and lack of report implies the test results were negative.”2 Although a few states provide websites or automated voice response systems where physicians can obtain screening results,3 tracking down newborn screening results can require many attempts per baby, which is a burden on office staff.

Newborn hearing screening results are hospital-based, not laboratory-based. The mechanism for reporting hearing screening results depends on the jurisdiction and, in some cases, hospital-level policy and procedures. Hospitals can communicate hearing screening results in various formats to stakeholders such as the family, the state Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) program, and audiologists. This non-uniformity of communications processes is one barrier to effective hearing screening follow-up.

Methods

Our goal was to develop a template that could carry NBS screening results as well as accommodate state variations in screening and reporting styles. We used a hierarchy of nested Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC®)4 panels to create this template, following an approach that has been successful for many other complex LOINC data capture processes.§ This approach provides a way to organize variables in a nested structure with their associated attributes: data type, cardinality,** UCUM©5 units of measure (for numeric variables), answer lists (for categorical variables), descriptions and help messages. The contents of this structure can be mapped to an HL7 message with each LOINC code and its corresponding test value carried in one OBX (observation result) segment within the HL7 message. Nesting can be reflected in the message by incorporating an OBR (observation request) segment for each node in the hierarchy.

The information in a LOINC panel can be represented by three relational database tables. One table carries a record for each LOINC term used in the panel with all of that term’s attributes. The second describes the relationship of a nested LOINC panel to its observation codes as a hierarchy. Each record in the second table contains a link to a parent LOINC term in the first table and other attributes that vary for a given LOINC term across panels. The third table contains answer lists for all of the categorical questions in the panel.

In order to create the LOINC panel for newborn screening, multiple agencies gathered information not only on NBS conditions, but also hearing variables and DBS card variables. Initial tables of NBS conditions screened in any state, associated measurements, and condition details were developed by the American Health Information Community (AHIC) Personalized Healthcare Workgroup’s NBS Subgroup, with help from the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) EHDI Program, and the National Newborn Screening and Genetics Resource Center (NNSGRC).6

The CDC EHDI Program helped develop a single set of LOINC answer codes for hearing screening methodology, results, and hearing loss risk indicators. A LOINC answer list includes all of the hearing loss risk indicators identified by the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing (JCIH) 2007 Recommendations.7 In an HL7 message, a single LOINC code for “hearing loss risk indicators” can repeat as necessary across many HL7 OBX segments to carry information about multiple risk factors. When no risk factors are identified, a single OBX segment should be used with the answer code for “None.”

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC) obtained and analyzed DBS cards from all U.S. NBS programs, and we developed a condensed set of questions and answer lists that covered the content represented in these cards. This standardized content included demographic information (such as baby and mother’s name and contact information – which go into the HL7 Patient Identification (PID) and Next of Kin (NK1) segments respectively), as well as birth history information that laboratories and clinicians may use to interpret and analyze screening results (such as history of blood transfusion or antibiotic administration prior to specimen collection). We worked with many organizations and individuals to develop and refine the answer lists for card variables, overall screening impressions, hearing loss risk indicators, hemoglobin disorders and more.

The National Library of Medicine (NLM) also worked with the CDC National Center for Health Statistics Division of Vital Statistics to create LOINC codes and corresponding answer lists for several card variables that reflect information contained in the 2003 revisions of the U.S. Standard Certificate of Live Birth. These variables include date of birth, time of birth, obstetric estimation of gestational age and mother’s education. Everything we did was reviewed and refined via feedback from many NBS experts and agencies as well as input during a formal Health Information Technology Standards Panel (HITSP) public comment period.

Regenstrief Institute assigned a unique LOINC code, unit of measure (for quantitative variables), and cardinality to each variable. For categorical variables, we defined formal answer lists and assigned each answer a LOINC answer code. We also included SNOMED CT codes where available (with permission from the International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation) for the answers that represent the conditions, and we will add SNOMED CT codes to other answer lists as they become available.

Based on all of the above work, we designed a comprehensive LOINC NBS panel, called the AHIC Newborn screening panel, which includes the 30 conditions specified by the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel, plus codes for any other conditions for which states screen. Each program can select the variables it needs, based on state policy, from the AHIC panel. Therefore, different states can include different subsets of variables in their reports, but each specific variable will be reported using the same LOINC code in a standard format across states.

After creating the AHIC Newborn screening panel, NLM worked with HRSA to develop guidance on constructing HL7 messages for newborn screening results using HL7 2.5.1 as specified by the Interim Final Rule on Health Information Technology.8 This guidance harmonizes with the Public Health Informatics Institute Implementation Guide,9 which focuses more on the administrative HL7 segments (e.g. MSH, PID, NK1), whereas this project focuses on detailed codes for the results “payload.”

Beyond the organizations mentioned above, the effort to produce a standard NBS message also required the expertise and guidance of the HITSP Population Perspective Technical Committee, lab system vendors, and state NBS programs (hearing and DBS).

Results

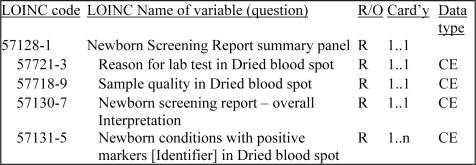

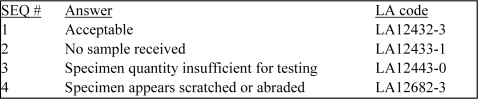

The LOINC NBS panel includes a total of 219 LOINC codes including 18 panel codes (used to group LOINC codes), 153 codes representing measured results or calculations and 30 codes for reporting interpretations and comments/discussion. In addition to individual analyte measurements and interpretations, the LOINC NBS panel contains summary interpretations (Figure 1) and card variables. The specification provides coded OBX segments for transmitting comments, instead of note (NTE) segments. Three of the summary variables (overall interpretation, reason for lab test in dried blood spot, and sample quality of dried blood spot) have specific answer lists, which are based on recommended practices and federal reporting standards (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Excerpt of the LOINC hierarchy showing codes and attributes (required/optional, cardinality and data type) for four of the eight variables in the Newborn Screening Report summary panel.

Figure 2.

Excerpt from the answer list for “Sample quality of Dried blood spot,” with sequence numbers and LOINC answer codes.

The LOINC NBS panel also includes 12 card variables (e.g. state of origin, date of birth, time of birth, birthweight, and unique serial number of current sample), with individual answer lists for the categorical variables (birth plurality, clinical events that affect newborn screen interpretation, hearing loss risk indicators, and mother’s education). The full LOINC NBS panel is available for download as a PDF or spreadsheet at http://newbornscreeningcodes.nlm.nih.gov/nb/sc/constructingNBSHL7messages/.

The LOINC NBS panel can accommodate results from all of the NBS programs and specifies the codes for an HL7 message. To show how these codes load into such a message, we created an annotated example HL7 v2.5.1 NBS message.10 The message includes segments for reporting NBS data including all of the card variables and summary reports, and some of the condition impressions and quantitative results. There are at least four potential destinations for NBS result messages: 1) the birth hospital, 2) the physician responsible for the infant’s on-going care, 3) the state NBS and state EHDI programs and/or public health department, and 4) national and/or regional registries of NBS data. The message was designed to be used to send data to all such recipients with tailoring where needed, e.g. removing identifying data before sending to central registries.

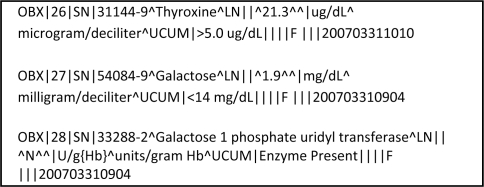

The 50-plus NBS DBS programs are served by some 36 NBS laboratories, a few main commercial information system vendors, and some state computer information departments. Because the numbers of involved organizations are limited, relative to other health information exchange contexts, rapid adoption of this standardized HRSA/NLM approach to NBS results messaging is possible. Indeed 15 months after the AHIC report to the HHS Secretary,6 three major NBS lab system vendors (Natus/Neometrics, PerkinElmer and Oz Systems) can demonstrate early versions of HL7 messages that meet this specification, and at least one laboratory is already sending NBS HL7 messages (Figure 3). In addition, one regional collaborative research project is assigning LOINC codes to the confirmed case data it collects from 46 U.S. states, Puerto Rico, and 80 international labs from 44 countries.

Figure 3.

Excerpt from a prototype Pennsylvania HL7 message, being developed by PerkinElmer and Oz Systems.

Discussion

The HRSA/NLM HL7 message guidance provides a uniform way to communicate newborn screening results in a computer-understandable form. As hospitals and office practice EHR systems adopt this guidance, they will solve some of the current problems with reporting NBS results. Most commercial EHRs already come equipped with HL7 inbound interfaces, and the Standards and Certification Criteria Interim Final Rule requires the support of LOINC and encourages the use of SNOMED CT in laboratory messages to meet the definition of meaningful use.8 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is also considering expanding the Medicaid EHR incentive programs to include NBS documentation as a pediatric clinical quality measure.11 If all U.S. NBS laboratories adopted the standard described here, EHRs could be designed to accept these messages out of the box, with no need to individually map and customize what would otherwise be large differences in NBS reporting formats by state.

Some regional health information exchanges (HIEs) provide web-based delivery systems that accept lab results messages from many sources (e.g. hospital laboratory, stand-alone radiology services) and deliver them in a uniform format to physician offices. HIEs already operate in Indiana, parts of Ohio, and Ontario, Canada (eCHN). Kentucky is developing an HIE that will use HL7 messages to provide NBS results as its inaugural effort. HIEs can routinely push NBS reports to anticipated providers, and, utilizing special linking tools, push to unanticipated providers as well. Unanticipated providers could also retrieve reports manually or by automated query. As providers adopt EHRs, the NLM/HRSA guidance standards would facilitate direct delivery of reports to the patient record with alert flags for abnormal results, thus avoiding the need for providers to go out of their way to look for the report or to assume “no news is good news.” As a result, the number and rapidity of NBS results reviewed should increase.

Having a standard message will also make it easier to collect regional and national data. Many of the conditions are extremely rare, with incidences of 1 in 100,000 births. Therefore, pooled data for all newborns screened are needed to study the effects of NBS follow-up programs and potential health interventions. For example, TSH results such as “borderline” or “slightly elevated” cannot be compared across programs, as opposed to quantitative results reported in a standard format. With such collections of quantitative data, researchers can improve screening methods and reduce false positive rates.

There have been differences of opinion in the NBS community about reporting numerical results as well as interpretations to pediatric care providers when screening tests are positive for a given condition. We support reporting numerical screening results whenever they can be reliably reported as the result of a standardized process. “Less than” or “greater than” results should only be reported when specific results are outside of the analytical range of the measurement. In the case of tests that produce nonnumeric results, such as hemoglobinopathy screening and DNA mutation analysis, the specific hemoglobin or mutation observed should be reported as opposed to just a qualitative interpretation such as “abnormal.” If cut-offs are obtained by evaluating percentiles rather than averages of analyte concentrations, the limitations of that approach should be explained.

Discussions with local pediatricians suggest that they tend to prefer qualitative reporting for negative NBS results because they are quick to read and digest. On the other hand, they prefer to get numerical values for the positives derived from quantitative measures, because the numerical values cue them to the likelihood that the positive is a true positive, needing close follow-up. Having the numerical results also makes it easier to discuss the results with the family.

Though challenges remain – including the unavailability of the follow-up physician’s name at the time of initial screening and a lack of electronic and automated linkages to vital records (and other systems that could help assure that all infants are tested and receive appropriate follow-up) – we are encouraged that standardized NBS messaging is being embraced so rapidly. This early success is testimony to the great cooperation among many organizations in the NBS community and their keen interest in the health of newborns.

Footnotes

Disclaimer and Acknowledgements

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC, HRSA, NIH, NLM, or the Department of Health and Human Services. This research was supported in part by the NIH/NLM Intramural Research Program.

The 30th condition, severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), was added on May 21, 2010; most states have not yet begun testing for SCID.

Including HL7 clinical genomic reporting, many large and complex Medicare forms (OASIS, MDS, CARE), HEDIS quality measures, laboratory test panels and standardized research measurements (PhenX and PROMIS).

Cardinality specifies whether the field is required, and whether you can have multiple repeated values.

References

- 1.Health Resources and Services Administration Recommended uniform screening panel of the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children [Internet] [cited 2010 July 15]. Available from: http://www.hrsa.gov/heritabledisorderscommittee/uniformscreeningpanel.htm.

- 2.Desposito F, Lloyd-Puryear MA, Tonniges TF, Rheinand F, Mann M. Survey of pediatrician practices in retrieving statewide authorized newborn screening results. Pediatrics [Internet] 2001 Aug 2;108(2):e22. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e22. [8 pages]. Available from: http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/108/2/e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Downs SM, van Dyck PC, Rinaldo P, et al. Improving newborn screening laboratory test ordering and result reporting using health information exchange. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010 Jan;17(1):13–18. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes [Internet] Indiana: Regenstrief Institute, Inc.; c1994–2010. [cited 2010 July 15]. Available from: http://loinc.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Unified Code for Units of Measure is a code system intended to facilitate unambiguous electronic communication of quantities together with their units. Available from: http://unitsofmeasure.org/

- 6.HHS Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology Newborn screening: AHIC use cases and requirements documents [Internet] 2008. Dec 19, [cited 2010 July 15]. Available from: http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt/gateway/PTARGS_0_10731_848131_0_0_18/NBSTerminology.pdf.

- 7.Joint Committee on Infant Hearing (JCIH) Year 2007 position statement: Principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2007 Oct;120(4):898–921. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health information technology: Initial set of standards, implementation specifications, and certification criteria for electronic health record technology. Interim Final Rule. 2010;170 45 C.F.R Part. Available from: http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/2010/E9-31216.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Public Health Informatics Institute (PHII) Implementation guide for reporting test results of newborn dried blood spot (NDBS) screening to birth facility and other interested parties [Internet] Jun, 2009. Available from: http://www.phii.org/resources/

- 10.National Library of Medicine Newborn screening coding and terminology guide [Internet] 2009. Sep 15, [updated 2010 May 3; cited 2010 July 15]. Available from: http://newbornscreeningcodes.nlm.nih.gov/.

- 11.Medicare and Medicaid programs; Electronic health record incentive program. Proposed Rule. 2010;495.6 42 C.F.R. Sect. Available from: http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/2010/E9-31217.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]