Abstract

Patients with end-stage renal disease must receive a kidney transplant or live on dialysis. Either treatment option introduces radical changes to their lifestyles and may result in significant psychosocial disruptions. Among these patients, young adults (YAs)—between age 18 and 30—are confronted with unique challenges because their life course is yet to be defined and their adulthood identity has not fully emerged. Partnering with the National Kidney Foundation of Michigan, we experimented with a web-based “peer-mentoring” intervention to create a user-driven, self-sustained online community. The objective was to help YAs develop “new normal” lives, restore social identities, and regain confidence in school and work. To foster a comforting online atmosphere for this vulnerable population, it is critical to use tailored technology designs catering to their needs and concerns. In this paper, we describe a prototype that we developed—ktalk.org, and report our findings from pilot-testing it with 38 YAs.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease—the ninth leading cause of death in the U.S.—affects the lives of more than 30 million Americans.1 It is a progressive, permanent condition in which kidneys are damaged and gradually lose their function. The final stage is chronic kidney failure, one type of end-stage renal disease (ESRD), where patients must receive a kidney transplant or ongoing dialysis treatments in order to stay alive. Of about 485,000 ESRD patients in the U.S., over 85,000 die each year.1

ESRD patients’ long-term health outcomes depend upon their awareness of the disease, adherence to treatments, and self-management of its related conditions. Yet, ESRD patients often experience limitations in their daily activities, poverty, and socially isolation, factors undermining their ability to effectively engage in self-care. 1 This has resulted in high rates of preventable hospitalizations, poor transplantation outcomes, and a significant, avoidable cost to the healthcare system and to the society.2

Young adults (YAs)—people between the ages 18 and 30—comprise less than 3 percent of all ESRD patients.1 While small in number, providing care to them presents significant challenges. Coping with the disease inevitably disrupts the social lives of these young patients and interferes with their ability to advance through the developmental stages of individuation, maturation, and independence.3 As a result, YAs with ESRD are more likely to react to their illness with anger and denial, and typically show higher rates of poor treatment adherence than their older counterparts.3–5 Hence, YAs are often characterized by their renal team staff as being unapproachable and uncommunicative, and providing care to them is further complicated by the fact that renal teams tend to be less experienced in handling this special population due to the small number of cases.4 For all of these reasons, YAs have much poorer health outcomes as compared to other adult populations; for example, while patients in this age group have he highest 1-year graft survival rates, their kidney transplant success ratio is the lowest primarily due to their failure to comply with required immunosuppressive medication regimens).5

Prior research has shown that as compared to traditional psychotherapy, psychosocial consultation services that encourage open communications with peers, families, and healthcare providers can help young patients with ESRD transition from pediatric to adult programs.4 Inspired by these findings, the National Kidney Foundation of Michigan (NKFM)—a non-profit, community-based organization—developed a YA empowerment program in which trained YAs act as volunteer peer mentors serving as role models, empathetic listeners, and information resources to other YA patients. While NKFM’s peer-mentoring programs targeting other adult populations have had great success in improving patients’ quality of life, employment rates, and self-sufficiency,6 the YA program had not fully taken off because the traditional face-to-face consultation model severely limited the program’s reach: YAs with ESRD are geographically scattered and most of them are on hemodialysis, a treatment that restricts their ability to travel, yet NKFM only has a handful of peer mentors specialized in this age group who are mainly located in Detroit and adjacent areas.

To address the issue, the social workers and YA peer mentors at NFKM partnered with a group of informatics researchers at the University of Michigan to create an online peer-mentoring community to empower YAs with ESRD. The objective was to help them develop “new normal” lives (e.g., going back to school or work), restore their social identities, and regain confidence in school and work. To foster a comforting online atmosphere for this vulnerable population, the design of the web community should reflect the needs, concerns, and preferences of the target audience. In this paper, we report our work on developing the online community, ktalk.org, and the findings from a pilot-evaluation of its prototype with 38 ESRD YA patients in Michigan.

Background

The increasing popularity of social media websites such facebook and twitter has also reflected in the healthcare domain, where there has been a growing interest in using “social software and its ability to promote collaboration between patients, their caregivers, medical professionals, and other stakeholders in health.”7, pg. 2 The prevalence of such “Health 2.0” technologies on the web makes it possible to provide psychosocial consultation services such as peer-mentoring through web-based healthcare-oriented communities. Besides convenient access transcending geographic boundaries, the anonymous nature of online communication can significantly reduce inhibition, invite open dialogue, and therefore promote active patient participation.8

YAs are a natural target audience for web-based peer-mentoring services. As compared to older adults, people in this age group are more technology-savvy and updating facebook statuses and following others on twitter is an integral part of their everyday lives.7, 8 Additionally, an online format may suit YA patients with ESRD whose self-image may be weakened by their illness.4 For instance, YAs may appreciate the ability to shield their true identities behind online callsigns, and the freedom to select peers with whom to associate.

Methods

Study Participants

According to the patient census data compiled by the Renal Network of the Upper Midwest (Renal Network 11), there are about 250 ESRD YAs living in Michigan. Because their identities were unknown and because virtually all of them would be under close medical supervision, we chose to recruit study participants through dialysis services, specifically through clinic social workers who are responsible for patient psychosocial support. Hence, we approached the Council of Nephrology Social Workers (CNSW) and inquired whether their members might be working with young ESRD patients between the ages of 18 and 30 and living in Michigan. Eighteen renal social workers helped us identify 56 eligible YAs from 18 dialysis units. All of these 56 YAs were invited to participate and 46 enrolled, representing approximately 25% of all YA ESRD patients in the state. For each YA participant, we also recruited three of his or her renal team staff as local study coordinators. Their roles included distributing study materials and helping the research team retain the participants in the study. Eight YA peer mentors previously trained by NFKM participated as online peer mentors and community moderators.

Prototype Development

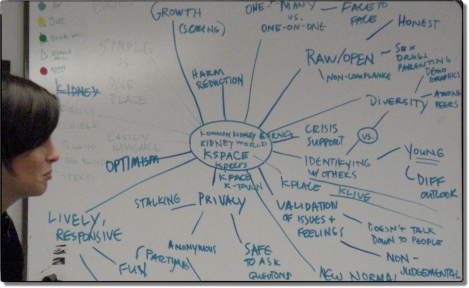

Rather than assembling a website quickly based on the researchers’ speculations regarding what the site ought to be, the social workers at NKFM—who have extensive experience working with YAs with ESRD, and the eight peer mentors—who volunteered to provide peer-mentoring in this study, helped us develop the vision for an online program tailored to the needs of young ESRD patients. In collaboration with these stakeholders, we conducted a series of participatory design activities, including a joint design workshop (see Figure 1), numerous rounds of software testing and feedback gathering, and a launch party to polish every fine detail of its design.

Figure 1.

A participatory design session to map out user needs and functional requirements for ktalk.

The resulting website, ktalk.org, contains five main features: (1) a “Videos” section containing interview clips in which the YA peer mentors discussed their life journeys with ESRD; (2) a “Talk” section in which users can post messages and take part in threads of discussions initiated by others; (3) a “Blogs” section for the YA peer mentors to share their feelings and their personal stories; (4) a “People” section listing the profiles of all registered users, which allows the community members to quickly know each another; and (5) a “Resources” section providing URLs of high-quality kidney disease websites and YA education materials provided by NKFM.

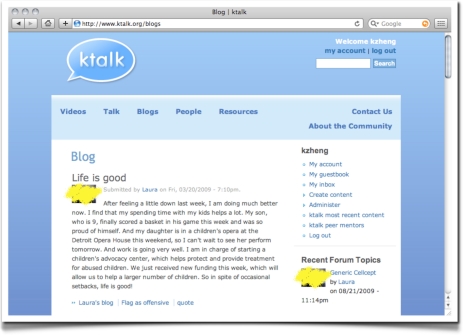

The programming of the web prototype was based on Drupal (http://drupal.org/), a popular, modularized open-source content management platform. Figure 2 exhibits a sample screen of the ktalk website.

Figure 2.

A sample screenshot of ktalk.org.

Research Design

In March 2009, a brochure and an initial invitation to sign up at ktalk were distributed to all study participants, followed by two additional rounds of individual recruitment activities. Participation was entirely voluntary and YAs created their own user registrations and profiles. During the study period, ktalk was open only to the YA ESRD patients participating in this research.

Three months later, local study coordinators helped the research team administer a survey to assess YAs’ feedback regarding ktalk and their needs for several specific online community features. The survey instrument also contained theoretically-informed constructs based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB), the technology acceptance model (TAM), and successor models to TAM.9, 10 These theoretical frameworks collectively postulate that a person’s decision to conducting a behavior, such as adopting a new technology, can be predicted by the person’s behavioral intention (int), which is in turn determined by the person’s perceived usefulness of the technology (pu), perceived ease of use (peou), and perceived facilitating conditions (pfc). By using these theoretical models to guide the data analysis of this research, we were able to evaluate which factors known to be influential in technology adoption might play a prominent role in determining the adoption success of ktalk among its intended users. Moderating factors such as gender were not included in the model testing due to small sample size.

The survey instrument (Table 1) contained 15 Likert-scale questions (all on a 4-point scale: “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “agree,” “strongly agree,” in addition to “does not apply”). They solicit user input along 4 distinct dimensions: (1) self-reported usage of ktalk; (2) prior experience with social media websites; (3) user needs for several specific online community features and user evaluation of these features’ quality of implementation at ktalk (in terms of effectiveness and ease of use); and (4) TPB and TAM informed theoretical constructs, among which facilitating conditions were assessed as technical robustness of the website (frequency of crashing, pfc1) and timeliness of receiving other members’ responses (pfc2). The Michigan Department of Community Health Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the research protocol.

Table 1.

The survey instrument.

| 1. Perceived actual usage 1.a Primary location of accessing ktalk.org (e.g., at home, in dialysis clinic) 1.b How frequently have you been using ktalk? |

| 2. Prior experience 2.a Besides ktalk, are you a member of other online community websites such as facebook? 2.b If so, do you use those websites to connect with other patients with kidney disease? |

| 3. Specific features (3 dimensions of user input are solicited for each of the features: whether it is important to the user, whether its implementation at ktalk is effective and is easy to use) 3.a Ability to find information on how to cope with kidney disease. 3.b Ability to get to know other kidney patients. 3.c Ability to stay in touch with other kidney patients. 3.d Ability to seek help from other kidney patients. 3.e Ability to express myself. |

| 4. Theoretical constructs 4.a The website crashes often in the middle of use. (pfc1) 4.b Questions I posted at ktalk received timely responses. (pfc2) 4.c Overall, I found ktalk useful to me. (pu) 4.d Overall, I found ktalk easy to use. (peou) 4.e I would continue to use ktalk. (int) 4.f I would recommend ktalk to others. (sat) |

Data Analysis

We first performed descriptive analyses of the survey responses. Then, we used logistic regressions to test the theoretical model to evaluate how the predicting factors may influence three main outcome variables: (1) intention to participate in the ktalk community (int); (2) actual usage assessed as whether the YA had ever registered at ktalk (act, 0: “no account”)—we used this surrogate measure because the actual site usage, such as number of messages posted, may vary based on a person’s participation style rather than reflecting her or his true level of engagement; and (3) self-reported usage (self-u), an ordinal variable consisting of “0, never,” “1, rarely,” “2, once a week,” “3, a couple of times a week,” and “4, daily”. Further, we assessed the overall satisfaction of ktalk users as signified by their willingness to recommend the site to other people (sat).

Results

Eight of the 46 YA participants dropped out from the study for various reasons; for example one patient moved out of the state and could no longer be reached. The final data included in the analysis were thus collected from 38 YAs. Among them, over 70% were diagnosed with ESRD after age 18; a majority (87%) were on hemodialysis, a treatment that requires three multi-hour visits to a dialysis clinic each week. Table 2 reports their gender, ethnic, and educational composition. A major proportion of these YAs with ESRD, 70%, are African Americans. No significant confounding effects were indicated (e.g., race and education, χ2 = 3.19, P = 0.074).

Table 2.

Key sociodemographics of participants.

| Variable | N(%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 26.4±3.9 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 22 (57.9) |

| Female | 16 (42.1) |

| Ethnic composition | |

| African American | 27 (71.1) |

| Caucasian | 10 (26.3) |

| Other | 1 (2.6) |

| Education | |

| High school or below | 21 (55.3) |

| College or above | 17 (44.7) |

Only a few YA participants, 9 out of 38, reported that they had never used a social media site. Eighteen had profiles on facebook, myspace, and/or blackplanet. Nonetheless, only two had used them to connect with other kidney patients. Among the 38 YA participants, 15 established an account at ktalk (40%). Six never did so yet they reported that they had been using it—four of these non-users actually indicated that they were on ktalk “a couple of times a week.”

As shown in Table 3, allowing the patient to express herself or himself was the online community feature desired most by the YA participants. Further, the evaluation of ktalk by its active members was positive overall, as indicated by high peou scores and favorable results with respect to their intention to continue to use ktalk and their wiliness to recommend ktalk to others. ktalk’s implementations of two online community features, “staying in touch with others” and “seeking help,” were rated somewhat lower, which might account for the relatively low rating of its perceived usefulness among the YA users. The ktalk users also encountered technical difficulties (crashing) initially which had been fixed overtime.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics

| Variable | Mean | |

|---|---|---|

| Importance | Qual. of ktalk†‡ | |

| “Finding information” | 3.1±0.8 | 3.3±0.6 |

| “Getting to know others” | 3.2±0.8 | 3.3±0.4 |

| “Staying in touch with others” | 3.1±0.8 | 3.1±0.6 |

| “Seeking help” | 3.2±0.9 | 3.1±0.6 |

| “Expressing oneself” | 3.5±0.8 | 3.5±0.7 |

| “Freq. of crashing” (pfc1)‡ | 2.0±1.0 | |

| “Response timeliness” (pfc2)‡ | 3.0±0.8 | |

| “Usefulness” (pu) | 3.2±0.8 | |

| “Ease of use” (peou) | 3.4±0.8 | |

| “Use intention” (int) | 3.3±0.8 | |

| “Satisfaction” (sat)‡ | 3.6±0.5 | |

Composite scores by taking an average of the “effectiveness” and “ease of use” measures;

ktalk users only, N = 15.

Table 4 reports the theoretical model testing results. Both unadjusted and adjusted statistics are shown because our sample size is small. Either binary or ordinal logistic regression was used as appropriate. The results based on the adjusted models revealed a significant positive influence of perceived ease of use (peou) on self-reported usage. Among the unadjusted results, peou and perceived usefulness (pu) are positively associated with intention to use (int); however, not with the actual usage measure.

Table 4.

Model testing results

| Independent variable | Dependent variable† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| int | self-u | act | sat‡ | ||

| pu | unadj. | 1.31* | ns | ns | ns |

| adjusted | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| peou | unadj. | 4.56*** | 1.59* | ns | ns |

| adjusted | ns | 4.14* | ns | ns | |

| pfc1 | unadj. | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| adjusted | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| pfc2 | unadj. | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| adjusted | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Pseudo R2 adjusted | ns | 0.29 | ns | ns | |

Log odds ratios, non-significant results are not shown;

ktalk users only, N = 15;

P < 0.1;

P < 0.05;

P < 0.001).

Discussion

While late adolescents and young adults are among the most active users of social media sites, significant barriers need to be resolved before ESRD patients in this age group will be able to benefit from online psychosocial consultation services. Our pilot-testing results showed that despite the encouragement from the study coordinators and researchers, more than half of the YA participants declined the opportunity to meet their peers at ktalk. Further, six participants who had never registered at ktalk reported in the survey that they were frequent visitors to the site. These findings may be reflective of the tendency of YAs with ESRD to deny their illness, refuse external assistance, and withdraw from social activities.3–5 Such defenses likely persist in a range of situations, of which our intervention may be one. Alternative behavioral interventions must be used to engage them in normal social lives so they can become active players in online patient communities. Additionally, future online interventions targeting this population might profitably be combined with companion, offline programs. What motivated some of the YAs to fabricate their activities at ktalk is unknown.

The theoretical model testing results showed that perceived usefulness (pu) and perceived ease of use (peou) seem to predict the participants’ intention to use ktalk, and peou predicts their self-reported usage. However, neither is associated with the actual usage measure. This finding is in general agreement with the TAM literature.10 Further, the insignificant results on actual usage may be partially explained by the fact that in the survey some of the YA participants did not report accurate usage information. Nonetheless, most ktalk users were positive about the site’s design and the concept of online peer-mentoring. They also offered many valuable suggestions that will inform the continued development of ktalk for future deployment at larger scales.

Conclusion

We developed an online patient community, ktalk.org, that uses the peer-mentoring model to empower young adults with end-stage renal disease. In this paper, we report our findings from pilot-testing a prototype with 38 YA participants living in Michigan. We found that while the web provides an ideal media for delivering psychosocial consultation services to patients in this age group, some barriers need to be addressed before such web-based interventions can fully live up to their promise.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all organizations and individuals who provided generous contributions to make this study possible. This research is financially supported by the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) and in part by Grant # UL1RR024986 received from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR).

References

- 1.NIDDKD . United States Renal Data System 2009 Annual Data Report. NIH; Bethesda, MD: [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. GAO. End-Stage Renal Disease: Characteristics of Kidney Transplant Recipients, Frequency of Transplant Failures, and Cost to Medicare. 2007;GAO-07-1117

- 3.Dittmann RW, Hesse G, Wallis H. Psychosocial care of children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease—problems, tasks, services. Rehabilitation (Stuttg) 1984;23(3):97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell L. Adolescents with renal disease in an adult world: Meeting the challenge of transition of care. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(4):988–91. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferris ME, Gipson DS, Kimmel PL, Eggers PW. Trends in treatment and outcomes of survival of adolescents initiating end-stage renal disease care in the United States of America. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21(7):1020–6. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perry E, Swartz J, Brown S, Smith D, Kelly G, Swartz R. Peer mentoring: A culturally sensitive approach to end-of-life planning for long-term dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(1):111–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarasohn-Kahn J. The Wisdom of Patients: Health Care Meets Online Social Media. California HealtHCare Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawn C. Take two aspirin and tweet me in the morning: How Twitter, Facebook, and other social media are reshaping health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(2):361–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Dec. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng K, Padman R, Johnson MP, Diamond HS. Studies in Computational Intelligence. Vol. 65. Berlin: Springer; 2007. Evaluation of healthcare IT applications: The user acceptance perspective; pp. 49–78. [Google Scholar]