Abstract

Study Objectives:

Disturbed sleep is a common complaint in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The majority of the research investigating relationships between sleep and patient-reported outcomes in RA has focused on pain and depression. Poor sleep may also affect disability, though this association has not been explored in RA. The present study represents a cross-sectional examination of the relationship between sleep quality and functional disability in 162 patients with RA. Depression, pain severity, and fatigue were examined as separate mediators of the relationship between sleep quality and disability.

Methods:

The sample had an average age of 58.47 years, and 76% were female. Participants completed the following questionnaires as part of a medication adherence intervention study: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Beck Depression Inventory-II, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form - 36, and the Health Assessment Questionnaire.

Results:

Poor sleep quality was significantly correlated with higher levels of depressive symptoms, greater pain severity, increased fatigue, and greater functional disability. Hierarchical regression analyses showed that sleep quality was not associated with functional disability when depression, pain severity, and fatigue were entered into the model. Separate mediation analyses of depression, pain severity, and fatigue revealed that pain severity and fatigue were mediators of the relationship between sleep quality and disability.

Conclusions:

Sleep quality has an indirect effect on functional disability through its relationship with pain severity and fatigue. Future research should investigate whether improvements in sleep can reduce disability in patients with RA.

Citation:

Luyster FS; Chasens ER; Wasko MCM; Dunbar-Jacob J. Sleep quality and functional disability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Sleep Med 2011;7(1):49-55.

Keywords: Sleep quality, depression, pain, disability, fatigue, rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a painful, chronic inflammatory disease characterized by proliferative synovitis causing swelling, morning stiffness, and deformity of multiple joints. Disturbed sleep is a major concern among persons with RA.1 Patients often report difficulty falling asleep, poor sleep quality, and feelings of nonrestorative sleep.2,3 Subjective self-reports have been corroborated with polysomnographic and actigraphic assessments that have revealed numerous awakenings and lower sleep efficiency compared to controls.4,5 Sleep disturbances in chronically ill adults have been associated with decrements in quality of life and psychological and physical function, as well as increases in morbidity and mortality.6,7 Given that disturbed sleep is a well-documented symptom of RA, sleep is an important consideration in addressing health and well-being in patients with RA.

Most of our knowledge about sleep in RA has focused on its relationship with pain and with mood.3,8–10 In particular, sleep problems, including insomnia symptoms and unrefreshing sleep, have been associated with a lower pain threshold at joint and non-joint sites and increasing pain severity.8,10 Wolfe and colleagues3 found pain and depression explained almost all of the variance in sleep measures in a cross-sectional study. Longitudinal analyses indicated that pain predicted sleep problems 2 years later, whereas sleep problems did not affect subsequent pain, and the interaction of high pain and sleep problems were associated with depression at 2 years.9

Fatigue is a common and distressing symptom of RA and has been associated with poor sleep, greater pain, increased depressive symptoms, and more functional limitations.11,12 RA patients report fatigue as overwhelming, variable, and different from normal tiredness.13 Clinically important levels of fatigue (≥ 2.0) were present in more than 40% of patients with RA when fatigue was measured by a 0-3 visual analog scale.14 In addition to pain, depression, and fatigue, poor sleep may also affect disability, though this association has not been explored in RA and may have important implications for long term care.

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Disturbed sleep is a common complaint among persons with RA and has been associated with patient-reported outcomes such as pain, depression, and fatigue. Physical disability is a distressing symptom of RA and may also be affected by poor sleep, although this association has not been explored in RA.

Study Impact: The proposed mediation model in the present study suggests that effectively treating sleep disturbances in RA might have beneficial effects beyond improving sleep. Addressing sleep problems via pharmacological or behavioral interventions may have a critical impact on the health and lives of patients with RA.

Physical disability resulting from polyarticular joint disease in patients with RA may limit their ability to carry out daily activities such as dressing, walking, grooming, and writing. These tasks can be further restricted by fatigue, pain severity, and depression, and possibly sleep disturbances and sleep quality, although less is known about this potential link in RA populations. Sleep quality has been found to predict pain-related disability in chronic pain patients.15,16 Furthermore, pain severity and depression were found to mediate this relationship. In RA populations, fatigue, pain, and depression have been found to be associated with physical disability.11,17,18 Wolfe and colleagues19 assessed functional disability using the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) and found pain and depression to be important determinants of functional disability in 1843 patients with RA. Given the links between sleep, pain, depression, and disability, an indirect pathway may exist between sleep quality and functional disability in RA.

The aim of the present study was to assess the relationship between sleep and disability using cross-sectional data from a sample of 162 RA patients. We examined whether sleep quality is associated with functional disability as measured by the HAQ. In addition, we hypothesized that this relationship would be mediated by depression, pain severity, and fatigue. More specifically, we expect poorer sleep quality would be associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms, greater pain severity, and increased fatigue, which in turn, would be associated with greater functional disability.

METHODS

Participants

This secondary analysis of data was part of a study to investigate the effectiveness of a multi-component intervention in improving medication adherence in adults with RA. Of the 641 adults with RA screened for entry in this study, 374 met the following eligibility criteria: a physician confirmed diagnosis of RA, presence of RA for ≥ 2 years, continuing patient in the practice site, age ≥ 18 years, and on a regular medication regimen for RA. For this paper, we conducted analyses on baseline data from 162 middle-aged and older adults with RA (≥ 40 years of age) who had complete data on the study variables of interest (Table 1). The mean age was 58.5 years (SD = 10.2), with a range of 40-82 years of age. The majority of the sample were women (76%, n = 123). Participants had an average of 4.01 (SD = 2.27) physician diagnosed comorbidities, with the most frequent comorbidities including high blood pressure, osteoporosis, and anemia. The average number of years since RA diagnosis was 13.9 (SD = 10.7).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of sample (n = 162)

| Age (SD) years | 58.5 (10.2), Range 40-82 |

| Gender (%) | 76% female |

| RA duration (SD) years | 13.9 (10.7), Range 2-56 |

| Number of comorbidities (SD) | 4.01 (2.27), Range 0-11 |

| Total number of prescribed RA medications | 2.43 (1.65), Range 0-8 |

| Prednisone (% prescribed) | 38% |

| Anti-TNF drugs (% prescribed) | 22% |

| NSAIDs (% prescribed) | 73% |

| Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 item vitality subscale (SD) | 45.10 (23.32), Range 0-95 |

| Beck Depression Inventory-II (SD) | 8.21 (6.75), Range 0-34 |

| Minimal (0-13) | 143 (84%) |

| Mild (14-19) | 17 (10%) |

| Moderate (20-28) | 8 (5%) |

| Severe (29-63) | 2 (1%) |

| Pain Severity (HAQ-pain) (SD) | 46.23 (27.10), Range 0-100 |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (SD) | 7.40 (4.07), Range 1-19 |

| Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ-disability) (SD) | 1.22 (0.76), Range 0-2.88 |

Beck Depression Inventory-II was calculated without the sleep item. RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire

Measures

Sociodemographic and Clinical Factors

Questionnaires developed by investigators in the Center for Research in Chronic Disorders at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Nursing were used to obtain data on sociodemographics, medical history, and currently prescribed medications. Participants were categorized as either taking or not taking each of the following types of medications: prednisone, anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) drugs, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Sleep Quality

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) measures self-reported sleep quality and disturbances over the last 1 month time period.20 The scale has 19 items and measures 7 components of sleep quality: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. A global PSQI score is obtained by summing the 7 component scores (range = 0-21). The PSQI global score accurately distinguishes “good sleepers” (PSQI total score ≤ 5) from “poor sleepers” (PSQI > 5) with a sensitivity of 89.6% and a specificity of 86.5%. The PSQI has acceptable psychometric properties including internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.73) and test-retest reliability.

Functional Disability

The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) is one of the most widely used patient-oriented outcome measures for assessing physical function in RA.21 The HAQ uses 20 questions to assess activity limitation in 8 dimensions of activities of daily living: dressing and grooming, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip, and common daily activities. Participants rate degree of difficulty for each activity on a 0-3 scale, where 0 = without any difficulty, 1 = with some difficulty, 2 = with much difficulty, and 3 = unable to do. A total disability score is derived by summing the scores of each item and dividing by the number of items to which responses were given. The range of scores is 0-3. The disability index of the HAQ has been validated in numerous studies, has been shown repeatedly to possess face and content validity, and possesses high convergent validity based on the pattern of correlations with other clinical and laboratory measures.22

Pain Severity

The HAQ-pain scale consists of a 15 cm visual analog scale anchored by 0 (no pain) and 100 (very severe pain).21 Participants are instructed to mark a line on the scale which indicates the severity of pain experienced in the past week. Scoring is accomplished by measuring the point at which the patient’s mark occurs on the line.

Depression

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) is a well-validated 21-item measure designed to assess depressive symptomatology.23 Scores for the items range from 0 to 3, reflecting the frequency with which the problem occurs. A total score is obtained by summing the scores for the 21 questions (range = 0–63). A total score of 0-13 is considered minimal range, 14-19 is mild, 20-28 is moderate, and 29-63 is severe. The BDI-II contains one item referring to sleep patterns, and these were omitted from the analysis to avoid spurious associations with the PSQI. The BDI-II has high internal consistency (ranging from 0.86 to 0.93) and high test-retest reliability.23

Fatigue

Fatigue was assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form - 36 (MOS SF-36) vitality scale.24 This scale comprises 4 questions including, “How much of the time during the past 4 weeks, did you feel full of pep?”, “did you have a lot of energy?”, “did you feel worn out?”, and “did you feel tired?” Responses to these items are recorded into a 0 to 100 scale with scales reversed as required. A scale score is created by averaging responses, with higher scores representing less fatigue.

Statistical Analyses

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS v. 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Summary statistics were presented as mean (SD), range for continuous variables (age, number of comorbidities, fatigue [SF-36 vitality], sleep quality [PSQI], pain severity [HAQ-pain], depression [BDI-II], and functional disability [HAQ]), and as frequencies for the categorical data (gender, prednisone use, anti-TNF use, and NSAIDs use). Bivariate relations between continuous variables were examined with Pearson product-moment correlation. Independent-sample t-test was used to examine differences in sleep quality, pain, depression, fatigue, and functional disability between those taking and not taking certain RA medications. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were used to test the study hypotheses. Tests of mediation were conducted according to procedures set forth by Baron and Kenny.25 To test for the significance of the indirect effects, we used Sobel’s z-test.26 Covariates were selected based on previous associations with sleep, pain, depression, fatigue, and disability27–29 and bivariate correlations and t-test analyses with the dependent variable. The following covariates were entered on the first step of the hierarchical regression analyses: age, gender, number of comorbidities, RA duration, prednisone use, and anti-TNF use.

RESULTS

The mean, standard deviation, and range for each measure are shown in Table 1. The majority (84%) of participants had a BDI-II score within the normal range (0-13). The mean HAQ pain score and disability score indicate moderate levels of pain and disability.30 According to the suggested cutoff point for the PSQI global score (scores > 5),20 61% of participants were poor sleepers. One-third (n = 54) of participants reported having pain that disturbed their sleep three or more times per week. Participants reported an average of 29.17 min (SD = 33.73) needed to fall asleep each night (sleep latency). The mean hours of actual sleep per night was 6.6 (SD = 1.4) (sleep duration). Sleep efficiency was computed by dividing reported hours of actual sleep by time in bed using participants’ reported bedtime and wake time (mean = 84.13, SD = 15.75).

Correlation analyses were conducted to examine the relationships between sleep quality, pain, depression, fatigue, functional disability, age, number of comorbidities, and RA duration (Table 2). Poorer sleep quality was significantly associated with greater pain severity (r = 0.48, p < 0.001), higher levels of depression (r = 0.52, p < 0.001), increased fatigue (r = −0.48, p < 0.001), and greater functional disability (r = 0.41, p < 0.001). Pain severity and depression were significantly correlated (r = 0.39, p < 0.001). Increased fatigue was associated with greater pain severity (r = −0.59, p < 0.001) and higher levels of depressive symptoms (r = −0.46, p < 0.001). Age was associated with both sleep quality and functional disability (r = −0.19, p < 0.05; r = 0.17, p < 0.05, respectively). Number of comorbidities was significantly correlated with both sleep quality (r = 0.22, p < 0.01) and functional disability (r = 0.43, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Correlations among study variables

| Functional disability | Sleep quality | Depression | Pain severity | Fatigue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep quality (PSQI) | 0.41** | – | – | – | – |

| Depression (BDI-II) | 0.38** | 0.52** | – | – | – |

| Pain severity (HAQ-pain) | 0.62** | 0.48** | 0.38** | – | – |

| Fatigue (SF-36 vitality) | −0.50** | −0.48** | −0.46** | −0.59** | – |

| Age | 0.17* | −0.19 | −0.23* | −0.01 | 0.05 |

| Number of comorbidities | 0.43** | 0.22** | 0.29** | 0.35** | −0.39** |

| RA duration (years) | 0.27** | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.09 | −0.02 |

p < 0.05

p < 0.001

PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; SF-36 vitality, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form – 36 vitality subscale

Participants taking prednisone had worse sleep quality (unequal variances t = −2.68, p < 0.01), greater pain severity (t = −3.36, p < 0.01), higher levels of depression (unequal variances t = −2.56, p < 0.05), greater fatigue (t = 2.70, p < 0.01), and greater functional disability (t = −3.87, p < 0.001) than those not taking prednisone. Participants taking anti-TNF drugs reported greater pain severity (t = −2.50, p < 0.05), higher levels of depression (t = −2.61, p < 0.01), and greater functional disability (t = −3.20, p < 0.01) than those not taking anti-TNF drugs. There were no differences in sleep quality or fatigue between participants taking anti-TNF drugs and those not taking these drugs. No differences in sleep quality, pain severity, depression, fatigue, or functional disability were found between participants taking NSAIDs and those not taking NSAIDs.

The relationship between sleep quality and functional disability was explored. In addition, the effect of depression, pain severity, and fatigue on the relationship between sleep quality and functional disability was assessed using mediation analyses. A hierarchical multiple regression was conducted to determine if sleep quality was associated with functional disability (Table 3). Results confirm that poor sleep quality is significantly related to greater disability, accounting for 7% of the variance after adjusting for age, gender, number of comorbidities, RA duration, prednisone use, and anti-TNF use (F6,155 = 20.21, p < 0.001). To test whether sleep quality is associated with functional disability, independent of depression, pain severity, and fatigue, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted with depression, pain severity, and fatigue entered into the second step of the model and sleep quality entered in the third step (Table 3). Depression, pain severity, and fatigue together accounted for 17% of the variance in functional disability (F3,151 = 23.57, p < 0.001); when sleep quality was then entered, no further significant variance was explained.

Table 3.

Hierarchical regression analyses for sleep quality predicting functional disability

| Step | Variables | β | t | ΔR2 | Total R2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Age (years) | 0.13 | 2.03 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 17.96*** |

| Gender | 0.14* | 2.13 | ||||

| Number of comorbidities | 0.39*** | 6.20 | ||||

| RA duration (years) | 0.26*** | 4.12 | ||||

| Prednisone use | 0.20** | 3.11 | ||||

| Anti-TNF use | 0.23*** | 3.58 | ||||

| 2. | Sleep quality (PSQI) | 0.30*** | 4.65 | 0.07 | 0.48 | 20.21*** |

| 1. | Age (years) | 0.13 | 2.03 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 17.96*** |

| Gender | 0.14* | 2.13 | ||||

| Number of comorbidities | 0.39*** | 6.20 | ||||

| RA duration (years) | 0.26*** | 4.12 | ||||

| Prednisone use | 0.20** | 3.11 | ||||

| Anti-TNF use | 0.23*** | 3.58 | ||||

| 2. | Depression (BDI-II) | 0.09 | 1.43 | 0.17 | 0.58 | 23.57*** |

| Pain severity (HAQ-pain) | 0.35*** | 5.16 | ||||

| Fatigue (SF-36 vitality) | −0.13 | −1.80 | ||||

| 3. | Sleep quality (PSQI) | 0.10 | 1.46 | 0.01 | 0.59 | 21.59*** |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

SF-36 vitality, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form – 36 vitality subscale; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II

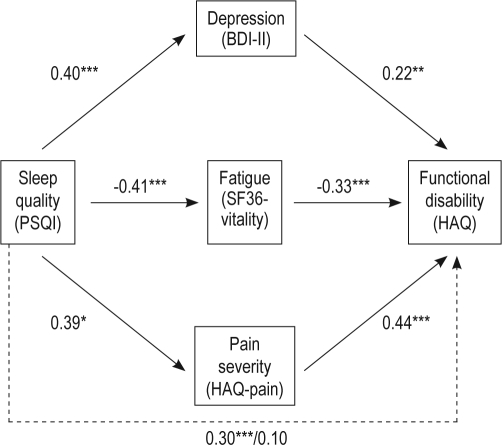

In order to further examine whether depression, pain severity, and/or fatigue are mediators of the relationship between sleep quality and functional disability, mediation analysis was conducted.25 To establish the first step of mediation, we examined the direct effects between sleep quality and functional disability. As seen in Table 3, poor sleep quality was related to greater functional disability after controlling for age, gender, number of comorbidities, RA duration, prednisone use, and anti-TNF use (β = 0.30, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001). To examine the second step in testing mediation, relationships were examined between sleep quality and the mediators (i.e., depression, pain severity, and fatigue). Sleep quality was associated with greater levels of depression (β = 0.40, SE = 0.12, p < 0.001), pain (β = 0.39, SE = 0.48, p < 0.001), and fatigue (β = −0.41, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001). To establish the third link necessary for testing mediation, we examined the relationship between each mediator and functional disability. Pain severity (β = 0.44, SE = 0.00, p < 0.001), depression (β = 0.22, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001), and fatigue (β = −0.33, SE = 0.00, p < 0.001) were associated with poorer functional disability after controlling for age, gender, number of comorbidities, RA duration, prednisone use, and anti-TNF use. In the final test of mediation, we examined the relationship between sleep quality and functional disability after simultaneously adjusting for depression, pain severity, and fatigue. As shown in Figure 1, the link between sleep quality and functional disability was no longer significant after accounting for the effects of depression, pain severity, and fatigue (from β = 0.30, p < 0.001 to β = 0.10, ns). The results of the Sobel test for mediation indicated that the indirect association between sleep quality and functional disability through pain severity and fatigue was significant (z = 5.44, p < 0.001; z = 5.46, p < 0.001, respectively). The mediated effect of depression was not significant (z = 1.88, p > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Pain severity and fatigue as mediators of the relationship between sleep quality and functional disability

The direct association between sleep quality and functional disability was no longer significant after accounting for the effects of depression, pain severity, and fatigue (from β = 0.30, p < 0.001 to β = 0.10, ns).

**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

DISCUSSION

The present study sought to determine whether sleep quality is independently associated with functional disability in RA, in accordance with findings in chronic pain.15,16 Poor sleep quality was found to be related to greater functional disability in the present study, after adjusting for age, gender, number of comorbidities, RA duration, prednisone use, and anti-TNF use. Additionally, the proposed mediation model indicated that sleep quality has an indirect effect on functional disability through its relationship with pain severity and fatigue.

The current study provides support for previous research in RA suggesting a significant relationship between sleep disturbances and depression.3,9 Our results suggest that poorer sleep quality is associated with greater levels of depression. In a cross-sectional study of 8676 patients with RA, depression accounted for 18% to 21% of the variance in the Medical Outcomes Sleep Questionnaire indexes and VAS sleep scale.3 The only study to date that evaluated both cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between sleep and depression in RA found sleep problems to be independently associated with depression in cross-sectional analyses, but sleep problems did not significantly predict subsequent depression except for those reporting high pain.9 These results are consistent with our findings and suggest that sleep disturbances are associated with higher levels of depression in cross-sectional analyses. The longitudinal relationship between sleep and depression in RA requires further investigation.

Our study found poorer sleep quality to be associated with greater pain severity. This finding is consistent with recent evidence suggesting that sleep disruption may lower pain threshold and enhance pain in RA and healthy adults.3,8,9,31 More specifically, deprivation of specific sleep stages, particularly REM, and reductions in sleep time increase pain sensitivity and vulnerability to pain.32 Alternatively, greater pain disturbs sleep.33

Poor sleep quality was associated with higher levels of fatigue in the current study, which is consistent with previous studies.5,11 An early study investigating polysomnographic sleep in RA patients suggested that fatigue in RA may be a manifestation of sleep fragmentation.5 Accordingly, sleep quality has been identified as a predictor of fatigue in 133 older adults with RA.11 Although disturbed sleep has been identified as a potential cause of fatigue by RA patients, patients often contribute fatigue to RA and describe fatigue as persist over time and occurring without a specific reason.13 Thus, additional research is needed to understand the role of disturbed sleep in fatigue among patients with RA.

The findings in the present study are consistent with previous research showing higher levels of depression, pain, and fatigue to be associated with greater functional disability in RA.11,19 Disability resulting from RA can have a devastating impact on the lives of patients by not only limiting ability to engage in activities of daily living, but also limiting discretionary activities such as socializing, leisure time activities, and hobbies.17 Pain and fatigue can prevent patients from engaging in daily activities which may aggravate swollen and tender joints and increase the sense of exhaustion. RA patients with depression may lack the motivation to overcome the restrictions caused by RA. Conversely, reductions in disability may be followed by improvements in depression, pain, and fatigue. Thus, the causal associations between depression, pain, and fatigue and disability may be bidirectional.

The proposed mediation model in the present study suggests that effectively treating sleep disturbances in RA might have beneficial effects beyond improving sleep. Benzodiazepine, triazolam, and a nonbenzodiazepine, zopiclone, improved self-reported sleep disturbances in early studies of patients with RA.34,35 A recent multi-center, placebo-controlled pilot study evaluated the efficacy of eszopiclone 3 mg, a nonbenzodiazepine, in 153 adults with insomnia comorbid with RA.36 At 4 weeks, almost one-half (48%) of eszopiclone-treated patients had no clinically meaningful insomnia as assessed by the Insomnia Severity Index, as compared to 30% of controls. Eszopiclone resulted in significantly better improvements in pain severity, tender joint counts, the activities domain of the HAQ, and the role physical and bodily pain scales of the MOS SF-36 compared to placebo. Although preliminary, these findings suggest that a nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic may be safe for treating insomnia in RA and has the potential to improve important patient-reported outcomes such as sleep, pain, disability, and quality of life.

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) may be another valuable approach to addressing sleep disturbances in RA. To date, no studies have evaluated the efficacy of CBT-I in RA. The use of CBT-I in chronic pain suggest that CBT-I may be beneficial in improving self-reported sleep efficiency, number of awakenings, and sleep onset latency.37 CBT-I significantly improved both immediate and long-term self-reported sleep and pain in older adults with osteoarthritis and comorbid insomnia.38 Fibromyalgia patients with insomnia complaints who were treated with CBT-I had greater improvements in subjective and objective sleep disturbances, pain, and mood than controls.39

There are several limitations of the present study. First, mediation according to Baron and Kenny25 assumes a causal link between the independent variable, mediator, and dependent variable. The cross-sectional data used in the analyses precludes causal conclusions about the directionality of the relationships between sleep, depression, pain severity, fatigue, and functional disability. It is possible that functional disability may affect depression, pain severity, and fatigue, which in turn may affect sleep quality. It is likely that the relationships are bidirectional to some extent. Longitudinal research is needed to examine the inter-relationships between these variables if causal associations are to be clarified.

Second, the present study only assessed sleep quality. Additional subjective measures of sleep disturbances (e.g., insomnia symptoms) and objective measures would yield a more global account of sleep in RA and enable further exploration of the relationships between different aspects of disturbed sleep (i.e., sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep fragmentation) and outcomes. Studies comparing subjective and objective measures (e.g., polysomnography and actigraphy) of sleep have shown that adults with RA tend to underestimate their sleep problems.2,5 Consequently, it is important to include both self-reported and objective measures of sleep disturbances to obtain a more comprehensive assessment of sleep in adults with RA.

Third, our study had no direct measure of fatigue and thus we used the SF-36 vitality subscale to assess fatigue. However, the SF-36 vitality subscale has been used previously in RA populations and compares favorably with other measures of fatigue such as the Multidimensional Assessment of Fatigue Scale and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Scale.40 Fourth, the majority of our study sample was women which may limit the generalizability of the study findings to men. Lastly, a number of comorbidities could have been contributing to poor sleep and functional disability in our sample. Although we controlled for the number of comorbidities, it was impractical to have controlled for all possible comorbidities which could have affected our study variables.

The results of this study suggest that poor sleep quality is associated with greater functional disability among patients with RA and this relationship may be explained by pain severity and fatigue. Although the directionality of these relationships requires further investigation, these findings suggest that disturbed sleep is a common symptom of RA and, if addressed via pharmacological or behavioral interventions, may have a critical impact on the health and lives of patients with RA. Moreover, pharmacological and cognitive-behavioral interventions that improve sleep disturbances may have beneficial effects on other patient-reported outcomes. Further research is needed to investigate whether improvements in sleep can reduce depression, pain severity, fatigue, and disability in patients with RA.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Patrick J. Strollo, M.D., for providing comments on this manuscript. Supported by NIH grants NR04554, NR00392, and HL082610.

ABBREVIATIONS

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- HAQ

Health Assessment Questionnaire

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- NSAIDs

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PSQI

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- BDI-II

Beck Depression Inventory-II

- MOS SF-36

Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36

- CBT-I

cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia

REFERENCES

- 1.Kirwan J, Heiberg T, Hewlett S, et al. Outcomes from the patient perspective workshop at OMERACT 6. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:868–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirsch M, Carlander B, Verge M, et al. Objective and subjective sleep disturbances in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a reappraisal. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:41–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe F, Michaud K, Li T. Sleep disturbance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: evaluation by medical outcomes study and visual analog sleep scales. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1942–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavie P, Epstein R, Tzischinsky O, et al. Actigraphic measurements of sleep in rheumatoid arthritis: comparison of patients with low back pain and healthy controls. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:362–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahowald MW, Mahowald ML, Bundlie SR, Ytterberg SR. Sleep fragmentation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:974–83. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:131–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manocchia M, Keller S, Ware JE. Sleep problems, health-related quality of life, work functioning and health care utilization among the chronically ill. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:331–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1012299519637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee YC, Chibnik LB, Lu B, et al. The relationship between disease activity, sleep, psychiatric distress and pain sensitivity in rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R160. doi: 10.1186/ar2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicassio PM, Wallston KA. Longitudinal relationships among pain, sleep problems, and depression in rheumatoid arthritis. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101:514–20. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Power JD, Perruccio AV, Badley EM. Pain as a mediator of sleep problems in arthritis and other chronic conditions. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:911–9. doi: 10.1002/art.21584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belza BL, Henke CJ, Yelin EH, Epstein WV, Gilliss CL. Correlates of fatigue in older adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Nurs Res. 1993;42:93–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollard LC, Choy EH, Gonzalez J, Khoshaba B, Scott DL. Fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis reflects pain, not disease activity. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:885–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewlett S, Cockshott Z, Byron M, et al. Patients’ perceptions of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: overwhelming, uncontrollable, ignored. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:697–702. doi: 10.1002/art.21450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolfe F, Hawley DJ, Wilson K. The prevalence and meaning of fatigue in rheumatic disease. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1407–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCracken LM, Iverson GL. Disrupted sleep patterns and daily functioning in patients with chronic pain. Pain Res Manag. 2002;7:75–9. doi: 10.1155/2002/579425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naughton F, Ashworth P, Skevington SM. Does sleep quality predict pain-related disability in chronic pain patients? The mediating roles of depression and pain severity. Pain. 2007;127:243–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz PP, Morris A, Yelin EH. Prevalence and predictors of disability in valued life activities among individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:763–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.044677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2428–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.18.2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfe F. A reappraisal of HAQ disability in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2751–61. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200012)43:12<2751::AID-ANR15>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fries JF, Spitz PW, Young DY. The dimensions of health outcomes: the health assessment questionnaire, disability and pain scales. J Rheumatol. 1982;9:789–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: a review of its history, issues, progress, and documentation. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:167–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. 1996;67:588–97. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JE, Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36).I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociol Methodol. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huscher D, Thiele K, Gromnica-Ihle E, et al. Dose-related patterns of glucocorticoid-induced side effects. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1119–24. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.092163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thyberg I, Dahlstrom O, Thyberg M. Factors related to fatigue in women and men with early rheumatoid arthritis: the Swedish TIRA study. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:904–12. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zamarron C, Maceiras F, Mera A, Gomez-Reino JJ. Effect of the first infliximab infusion on sleep and alertness in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:88–90. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.007831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: dimensions and practical applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:20. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roehrs T, Hyde M, Blaisdell B, Greenwald M, Roth T. Sleep loss and REM sleep loss are hyperalgesic. Sleep. 2006;29:145–51. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lautenbacher S, Kundermann B, Krieg JC. Sleep deprivation and pain perception. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:357–69. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith MT, Haythornthwaite JA. How do sleep disturbance and chronic pain inter-relate? Insights from the longitudinal and cognitive-behavioral clinical trials literature. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8:119–32. doi: 10.1016/S1087-0792(03)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drewes AM, Bjerregard K, Taagholt SJ, Svendsen L, Nielsen KD. Zopiclone as night medication in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1998;27:180–7. doi: 10.1080/030097498440787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walsh JK, Muehlbach MJ, Lauter SA, Hilliker NA, Schweitzer PK. Effects of triazolam on sleep, daytime sleepiness, and morning stiffness in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:245–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roth T, Price JM, Amato DA, Rubens RP, Roach JM, Schnitzer TJ. The effect of eszopiclone in patients with insomnia and coexisting rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot study. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11:292–301. doi: 10.4088/PCC.08m00749bro. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jungquist CR, O’Brien C, Matteson-Rusby S, et al. The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia in patients with chronic pain. Sleep Med. 2010;11:302–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vitiello MV, Rybarczyk B, Von Korff M, Stepanski EJ. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia improves sleep and decreases pain in older adults with co-morbid insomnia and osteoarthritis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:355–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK, Krystal AD, Rice JR. Behavioral insomnia therapy for fibromyalgia patients: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2527–35. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.21.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hewlett S, Hehir M, Kirwan JR. Measuring fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of scales in use. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:429–39. doi: 10.1002/art.22611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]