Abstract

Introduction

Younger breast cancer survivors often lead extremely busy lives with multiple demands and responsibilities, making them difficult to recruit into clinical trials. African American women are even more difficult to recruit because of additional historical and cultural barriers. In a randomized clinical trial of an intervention, we successfully used culturally informed, population-specific recruitment and retention strategies to engage younger African-American breast cancer survivors.

Methods

Caucasian and African American breast cancer survivors were recruited from multiple communities and sites. A variety of planned recruitment and retention strategies addressed cultural and population-specific barriers and were guided by three key principals: increasing familiarity with the study in the communities of interest; increasing the availability and accessibility of study information and study participation; and using cultural brokers.

Results

Accrual of younger African-American breast cancer survivors increased by 373% in 11 months. The steepest rise in the numbers of African-American women recruited came when all strategies were in place and operating simultaneously. Retention rates were 87% for both Caucasian and African American women.

Discusssion/Conclusions

To successfully recruit busy, younger African American cancer survivors, it is important to use a multifaceted approach, addressing cultural and racial/ethnic barriers to research participation; bridging gaps across cultures and communities; including the role of faith and beliefs in considering research participation; recognizing the demands of different life stages and economic situations and the place of research in the larger picture of peoples’ lives. Designs for recruitment and retention need to be broadly conceptualized and specifically applied.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

For busy cancer survivors, willingness to participate in and complete research participation is enhanced by strategies that address barriers but also acknowledge the many demands on their time by making research familiar, available, accessible and credible.

Keywords: Younger breast cancer survivors, Culturally informed recruitment and retention strategies, Minority research participation

Introduction

Recruiting and retaining racial/ethnic participants for clinical trials and other intervention studies of cancer survivors remains a challenge [1]. Recruitment strategies for African Americans (AAs) must take into account the sociocultural barriers to participation such as faith traditions, cultural experiences and beliefs, the disproportionate number of individuals with limited socioeconomic resources and busy, stress-filled lives [2, 3]. The use of a culturally informed, community-based approach that involves working in partnership with natural informal support persons and networks [4–6] and is responsive to the beliefs, attitudes and daily lived experiences is important to successful recruitment and retention efforts [7, 8]. For younger AA breast cancer survivors who are dealing with complex life demands, research participation needs to be perceived not as a luxury but as an important and valued part of their self care. This may be especially true for cancer survivors who may be anxious to leave their cancer experiences behind and to become re-immersed in their “normal” lives. For AAs, relationships, faith and trust are common cultural themes relevant to research participation.

Relationships

AAs have historically used extended familial and friendship networks [9] to share tangible and intangible resources with people outside the traditional nuclear family including material resources, information, encouragement and validation, especially when members have personal or health problems [10, 11]. Information that comes through these networks is likely to be more available, accessible, relevant and trusted than information that comes from other sources. Many AAs have experienced racial microaggressions in everyday life—brief, common indignities, both intentional and unintentional, that convey hostility, dismissal, derogatory feelings and insults to people of color [12]. The cumulative effects of such microaggressions are likely to contribute to mistrust of information coming out of majority establishments, including the health care system and academic research [12]. Using informal support persons or cultural brokers who serve to bridge the gap between health care providers and the communities they serve has yielded recruitment success by enhancing trust and familiarity with the sources of information [6, 13].

Faith

AAs have been described as being fatalistic about cancer [14, 15], and this has been linked to faith traditions that put problems in God’s hands. Sometimes the belief that God is in control is misinterpreted by those outside the culture as passivity toward dealing with their health problems. For many AAs, however, a strong faith in God’s control is compatible with an active approach to treatment that includes various actions such as prayer, seeking treatment, and participating in research [16]. In fact, faith is one of the major ways in which many AAs actively deal with life problems, including illness or the threat of illness [16–18] and, for survivors, fears of recurrence. The relevance of research participation can be linked to faith as people consider whether their participation in research fits with their faith as well as their priorities.

Trust

AA distrust of research-related information is linked to the historical and more contemporary abuses of trust in research and in medical care that stem from both overt and subtle forms of racism [19–23]. Building trust requires working with and through community gatekeepers, partners and cultural brokers to make study information available and meaningful to the target population [24, 25]. The endorsement of the research by key community members can increase the study’s relevance to the targeted community. Further, integrating cultural brokers into the research team, making them visible to the community and providing the team with an insider perspective, can also enhance trust [24, 25].

Responsiveness

Finally, successful recruitment and retention efforts involve being responsive to the issues and needs of the targeted population. For younger women survivors, their multiple priorities of work, family, friends and often, school or careers impose complex demands on their time. Hence, strategies that are sensitive to these unique circumstances are essential. Giving back to the community of interest is a way to enhance responsiveness—especially in response to their expressed needs. Doing so may enhance trust by communicating that the investigators have more than their own interests in mind [24, 25].

This paper reviews issues of importance in recruiting AA survivors in research and describes our research team’s effective use of culturally informed, population-specific recruitment and retention strategies to engage younger AA breast cancer survivors in a clinical trial of a psycho-educational intervention designed to help them manage uncertainties and long term treatment side effects.

Methods: strategies for recruitment and retention of African American breast cancer survivors

Overview of intervention trial

The Younger Breast Cancer Survivors: Managing Uncertainty (5R01NR010190) study was a randomized clinical trial of a psycho-educational intervention designed to assist women to deal with their fears of cancer recurrence, deal with communication issues around the breast cancer, identify positive directions for their lives, and manage long-term symptoms and side effects of treatment. Caucasian and AA women under 50 who were at least 1–4 years from completing treatment for Stages 1–IV breast cancer were recruited and randomized to the intervention or to a control condition. Data on stress and symptom-related outcomes, including salivary cortisol as a biological measure of stress, were collected from all women at baseline, 4–6 months post-baseline, and then at a stress event like a mammogram or doctor visit. Data were also collected from all women 8–10 months post baseline. Women randomized to the intervention received a CD, a guide booklet related to long-term treatment effects, a breast cancer resource guide and four scheduled phone calls from a nurse over the 4–6 weeks following baseline data collection. The calls were scripted to help the women use the intervention materials effectively. Women in the control group had four scheduled phone calls from a graduate student during which they were encouraged to talk about their breast cancer experiences at diagnosis, during and after treatment and as a survivor. They received no intervention materials until after completing participation in the study.

Recruitment strategies: targeting the barriers

Our goal was to counter the known barriers by making all aspects of our study inviting, relevant, convenient, appealing and respectful of potential participants’ busy lives. In addition to engaging and recruiting these survivors, we wanted to provide a consistent, positive, meaningful research experience that would support their completion of the study.

Pilot research study findings provided insight into the socio-environmental context of younger breast cancer survivors. We found that Caucasian and AA younger breast cancer survivors varied greatly in income and education as well as family background, and were extraordinarily busy in any number of ways. AA women were disproportionately more often raising families as a single parent while working, going to school, caring for extended families, being actively involved in community and church activities and coping with their fears of recurrence. A disproportionate number of AA women were also struggling financially. The challenges, stressors and priorities of their daily lives, in combination with traditional racial/ethnic barriers to research participation, made it particularly difficult for them to see the value of research participation.

Therefore, strategies for recruitment and retention of younger AA breast cancer survivors were based on three guiding principles: increasing familiarity with the study in the communities of interest; increasing the availability and accessibility of study information and study participation; and using cultural brokers to help us accomplish these goals. Many of our specific strategies evolved over time and in response to aspects of the study that were problematic for participants. Table 1 summarizes the strategies used and the goal(s) for each.

Table 1.

Strategies for recruitment and retention

| Strategies | Familiarity | Availability/Accessibility |

|---|---|---|

| Revision of Recruitment Materials/Procedures | ||

| Brochure pictured young AA women; lacked jargon; invitational, relevant | X | X |

| Personal contact: recruiter photos & biosketch in newsletter | X | X |

| AA recruiters used for AA recruitment | X | X |

| Study Methods Designed to be Responsive to Needs of Younger AA women | ||

| Eligibility criteria: Time since treatment completion expanded from 1 to 4 years, rather than 2–4 years | X | |

| Timeline for participation decreased from 10 to 8 months. | X | |

| Recruitment focused only on AA women starting 7-08 | X | |

| Developed and sent to all participants a Community Resource Guide: County HCP resources for uninsured and under insured with guidelines for eligibility | X | |

| Waiting list for women if wanted to delay study entry | X | |

| NC Breast Cancer Resource Guide given to participants | X | |

| Fitting Intervention to Participants’ Lives | ||

| Intervention materials, data collection strategies and scheduled phone calls convenient for participants | X | |

| Prepaid cell phones made available if participants had no phone (Used supplemental funding) | X | |

| Community Groups and Organizations/Community Partnerships | ||

| Contacted Breast Cancer support groups, especially those for African Americans and younger women: Save Our Sisters, Sisters’ Network | X | X |

| Presentations about the study at workshops; block walks to disseminate information | X | X |

| Community Partner: Project Connect | X | X |

| Attended meetings; recruitment training for lay health advisors; newsletter information. Obtained supplemental funding for meals during training and gas cards for travel | ||

| Community Partner: Crossworks | X | X |

| Meeting presentations; trainings for community health advocates related to study information for dissemination; Supplemental funding obtained for meals during training and gas cards for travel | ||

| Working with African American United Methodist Churches | ||

| Black Methodists for Church Renewal-letters sent to Eastern United Methodist Bishops requesting study information be sent to local pastors | X | X |

| Church supported cancer support groups; study information put in church bulletins | X | X |

| General Advertising of Study | ||

| Public service announcements—AA radio stations and AA newspapers | X | |

| Brochures sent to nail salons | X | |

| Posters, booths, gifts at AA church health fairs, community events, e.g., health fairs, street festivals, block walks, church events | X | |

| Local minor league baseball game: booth, banner, softballs, study information | X | |

| Mass e-mails to faculty and staff at universities in the area | X | |

| Local United Methodist magazine—study information | X | |

| Enhanced study website | X | |

| Meetings, Conferences & Presentations | ||

| UNC Lineberger Cancer Center conference: presentation & brochures | X | |

| Lincoln Community Health Center Breast Health Day presentation about breast cancer; booth, & gifts for participants | X | |

| Carolina Community Network (CCN): meeting with Project CONNECT, other community organizations & UNC faculty/staff | X | |

| Retention Strategies | ||

| Recruiters helped women plan ahead for study period | X | |

| T1: Intervention materials delivered in person; data collectors reviewed and trained women in salivary cortisol selection | X | |

| Intervention calls or control calls scheduled at subject’s convenience | X | |

| Attentional control condition for control participants; intervention materials sent after study completion | X | |

| T2, Ts & T3: Consistent data collection; ongoing contact, extra trips to pick up saliva samples | X | |

| Financial incentives for completion of T2 & T3 data collections | ||

| Flexibility of and personal contact with data collectors | X | |

| Individual letters and retention gifts mailed every 2 months; birthday cards sent to all participants. | X | |

Enhancing familiarity

Familiarizing the communities of interest with our study involved dissemination of study information in many different ways to ensure that people would hear about the study in a variety of times and places, making it familiar. Organizing this labor intensive effort involved identifying a research team member to be the liaison for each activity. We targeted the community at large through public service announcements on radio stations and in newspapers serving the AA community. We also had research team members with information at community events (See Table 1 for specific examples). Having a table at the very popular local minor league baseball games turned out to be a way to disseminate study information beyond direct contacts with women. We gave out rubber balls with the study title and a 1–800 telephone number to anyone who came by the table. Study brochures were also available and research staff answered questions and talked briefly about the study. There were several interesting and unexpected results. First, a number of men, after walking by—sometimes repeatedly, stopped to ask what the study was about, to get a ball (“for their children”) and then revealed that they had a wife, girlfriend, mother, sister or friend who was a breast cancer survivor and said they would take the study information to them. The balls essentially “bounced throughout the community” and some people heard about the study by asking where the balls came from. We also distributed the balls at other events and recommended them as stress reducers (they were soft and squeezable) as well as good hand exercisers. Thus, for a very small investment, we found an interesting and fruitful way to make our study familiar in the community.

Working with AA churches

Here we presented our research as fitting with health ministries, established and credible entities in AA churches. Developing and sustaining relationships was time and labor intensive. Our most efficient approach involved working with a regional network of United Methodist Churches through an AA member of our team, who was not only an active leader in her church network, but also an expert in diversity issues and strategies for bridging cultural gaps. She developed a letter (See Insert A) to the Bishops of United Methodist churches across the Eastern part of the state, connecting beliefs to active participation in research. The Bishops then disseminated the study information to pastors in their districts, who were asked to convey the information to their parishioners. The pastors were asked by their Bishops for feedback on when and how the information was given to parishioners, using the organizational hierarchy to hold them accountable for dissemination.

Partnerships with community organizations

Familiarity was enhanced by relationships with well-known organizations and groups that were willing to serve as informal cultural brokers to enhance the credibility of our study. Many groups already played a role in meeting the needs of AA cancer survivors. While members of our research team participated in meetings and in trainings for community health advocates, the most important roles were played by key people who already had the respect of the community. They included community health advocates from our community partner organizations, pastors, and leaders of groups like Save Our Sisters and Sisters Network. These people were part of the natural helping networks that bridged the gap between academic researchers and the communities [26]. Their goal was to use those bridges to increase the participation of AA women in our research [26].

One of our community partner organizations, Project CONNECT, had a major mission of increasing research understanding and participation of AAs. Their staff trained community research advocates to educate the community about research, particularly clinical trials. A second community partner, CrossWorks, had as its primary mission improving the health of the community. They trained lay health advocates who attended community events, especially health fairs, to provide health education. We worked with both organizations to teach them about breast cancer in AA women, about survivorship issues and about our study and what it offered. Using the training models already in place, with some additional funding, we were able to provide a meal for the advocates during training sessions and distribute gas cards for them to travel to the training. Thus we engaged them as partners and broadened our reach in the community. All of the advocates were known and respected already, and they were committed to their mission, and were a constant presence at community events and organizations.

Availability/Accessibility

In addition to making our study familiar to AA communities, we worked to make information easily available to potential participants, by distributing study information through traditional relationship networks. We enhanced our study website to provide more information of interest to AA women, presented information at breast cancer survivor groups, had booths or did presentations at key health centers and conferences, and attended breast cancer events like walks and races, handing out study brochures, approaching survivors and discussing the study. We made the study information culturally appealing, relevant and convenient to potential participants. Our brochure had pictures of young survivors, including several AA women. The language and tone of the information in recruitment materials were developed, with the help of AA team members, to be friendly to younger women in the AA community. We used lay language, pictures and phrasing to make brochures, letters and posters warmer, more conversational and inviting. For example, the study newsletter we sent out with recruitment materials featured pictures of our team’s recruiters and nurse interveners, not only to show that there were many AAs on the research team, but also to introduce the team as real people, women with a commitment to helping breast cancer survivors, who had names and lives and were not just research team members.

AA recruiters

Initially, we had some difficulty recruiting AA survivors by telephone. Some would not respond to phone calls or to phone messages. We started, whenever possible, to use AA recruiters to recruit AA women. These recruiters noted that their comfort in interacting with diverse populations enabled them to use culturally relevant dialogue. They also made follow-up calls from home so that the women could see their names, not just the name of the university and an unknown telephone number. Because it was important to AA women to know a caller’s name, they were more likely to be responsive to recruiters’ calls. Moreover, telephone calls placed in the evening hours were much more successful than those made during the typical work day when most of the women we were trying to recruit were at work.

Community resource guide

Recruiters used the recruitment time to identify questions and concerns from potential participants that were not always directly related to the study. One concern expressed by the women was that they were not receiving any follow-up care as survivors, because they were underinsured or uninsured. In response, we developed a community resource guide which listed either free or income-based county and local clinics with their eligibility criteria for getting care. The guide also provided information about free mammograms in various communities; and other community resources. We sent this resource guide to all study participants and encouraged them to share it with other women in their communities who might benefit. This helped us to reach out to more low income breast cancer survivors and to women who might share the information with others.

Timing of participation

To enhance flexibility for joining the study, we generated a waiting list of women who wanted to participate, and met the eligibility criteria, but for a variety of reasons could not fit study participation into their lives at the time when they were contacted. Several women had recently lost close family members; some were dealing with an illness themselves or a family member’s illness; and other women were extremely busy at work or going through life transitions. These women, with their permission, were contacted at a later time that we negotiated with them.

Fitting the intervention to participants’ lives

The study was designed to be as convenient as possible to participants. Data were collected in participants’ homes and the intervention was delivered by CD, manual, and telephone. It was easily adaptable to busy participants’ schedules and did not involve travel or other expenses. Strategies for managing uncertainty were recorded by professional actors on a CD so that the women could listen to them in preparation for their phone calls wherever it was convenient—in their cars, on their computers, etc. The guide, tabbed for each topic, was very easy to use. It was given to all women in the intervention group to keep and use whenever they had questions or needed resources. The telephone calls from nurse interventionists were always pre-scheduled at times convenient to the participants—including nights and weekends. For control group women, home data collection and the four phone calls to discuss their breast cancer experiences were also pre-scheduled for their convenience. Low-income women who could no longer afford phone service were provided with prepaid cell phones so they could participate.

Retention

Challenges for any longitudinal intervention trial include maintaining interest and willingness to complete the intervention and data collections and, for control participants, maintaining interest and completing data collection without an intervention. In addition to strategies for recruitment, our research team addressed barriers to retention for both intervention and control participants. Data collection schedules over 8–10 months, including multiple samples of salivary cortisol for 3-day periods, were demanding. In addition, many women in our target population were not familiar with psycho-educational interventions. To address these issues, we used maximal flexibility and, to the extent possible, met the women’s individual needs in scheduling their participation. For example, recruiters explained the timeline for participation and asked women to take into consideration already scheduled important events during the period of time they would be in the study. In this way, they helped the women plan ahead for uninterrupted participation and conveyed their acknowledgement of the women’s busy lives.

In order to engage survivors early in the study, the data collectors, when delivering the intervention materials to women in the intervention group at home, explained the materials and encouraged women to review them before the intervention calls. This strategy of early engagement has been found to be a predictor of retention [8]. All intervention telephone calls were scheduled ahead of time at the participant’s convenience, to encourage ongoing participation and completion of the intervention.

We also wanted to engage survivors in the control group early in order to retain them in the study, even though they would not get the intervention materials until they had completed data collection. To do this, the control group women talked with a graduate student by phone four times about their cancer diagnosis, treatments, side effects and survivor experiences.

To keep women engaged in the study, the same data collectors collected all data for any given participant’s appointment, minimizing the time, effort and expense of participation. Also, to encourage retention, participants were given a 1–800 telephone number and a study e-mail address they could use. To make things as convenient as possible for the women, data collectors delivered equipment to all participants, explained and demonstrated saliva collection procedures, and had the women practice so that the process was clear to them. We also made it easy for women to return the saliva samples by having data collectors pick up the samples at their homes.

If at any time a data collector was told by a survivor or intuited that she was likely to drop out, the data collector, and at times the recruiter, would call the women to try to identify and resolve any issues that could be addressed. If a data collector had difficulty scheduling a second or third data collection visit, she called the participant’s original recruiter, who would then call or e-mail the woman to try to resolve any problems with scheduling. We acknowledged to participants that we understood that they had other priorities, including unexpected obligations, and we were as flexible as possible in helping them complete the study.

All the women in the study received a brief letter every 2 months, reiterating the value of their contribution, and including a carefully chosen incentive gift. Gifts were inexpensive but useful and included such things as calculators, insulated lunch boxes, stress balls, jar openers, post-it notes and pens, all with the study name and 1–800 telephone number. Also, with the first data collection, a NC Tar Heel magnet was given to the women to keep near their calendars and fill in the date and time for their next data collection and calls. In addition, all participants received a $20 check at the time of each data collection. The women’s birthdays were acknowledged with cards and, as mentioned earlier, all women received the community resource guide about free or income-based follow-up care. The letters and gifts were designed to be a message to the women that we appreciated and valued their ongoing participation in the study.

Results

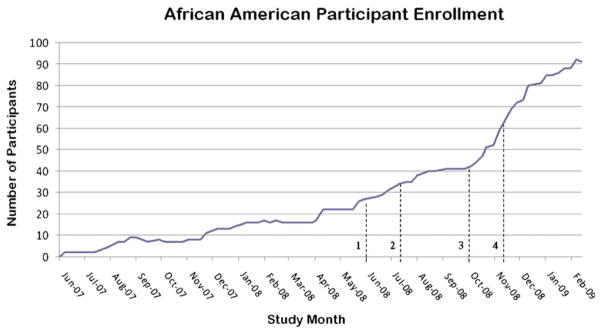

As a result of these multi-faceted strategies, we improved our accrual of younger AA breast cancer survivors by 373% in 11 months (from 22 to 104 individuals). Figure 1 gives the timeline of AA subject enrollment from the beginning of recruitment through the final month of recruitment. At the point when community engagement strategies began, the numbers of AA women recruited began to increase. The steepest rise in the numbers of AA women recruited came when all strategies were in place and operating simultaneously. Our final sample contained 31% AA breast cancer survivors, exceeding the approximately 21% proportion of AAs in the state.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of activities and accrual. * Note: 1 Posters, PSA, 2 Stopped Caucasian recruitment, Emailed listservs, 3 Tumor registry queries at 7 sites, 9 events, Intramural grant, Meetings with organizations, 4 CRA training

Our retention rates were 87% for both Caucasian and AA women. Common reasons among AA women for not completing the study included study staff losing contact with them or the women saying they were too busy, often with a combination of work and family issues. For Caucasian women in the study, the most common reasons for not completing the study were loss of contact, another illness, or recurrence of their breast cancer.

Discussion: lessons learned

As a result of our attempts to enhance the recruitment and retention of young AA breast cancer survivors, we uncovered needs that affected participation and were major concerns for this population. Survivors’ problems with follow-up care, limited or no insurance and inability to pay for care, severe economic constraints and lack of information about resources for care demanded that we be as responsive and flexible as possible in order to engage these women in our research. In the process, we discovered ways to give back to the women in these communities to meet their needs, building good will and trust. For example, the community resource guide we developed for participants addressed important gaps in information or and allowed some uninsured survivors to obtain follow-up care. Our approach utilized some principles of community-based participatory research in that we took differences in cultures and health beliefs into account, tried to address historical reasons for mistrust and utilized significant community involvement in partnering with community organizations and advocates within the community [6].

While our team was familiar with and had done some work with AA churches, especially through health ministries, the letter written by a member of our team to United Methodist Bishops was a major lesson learned on several levels. In terms of reaching out widely to AA communities, using the United Methodist church network leadership to partner with local pastors gave us an efficient and effective way to reach out to AAs throughout the Eastern part of the state. Partnering with these key leaders through our team member’s insider knowledge of the church network organization and operations, we were able to connect with the key gatekeepers who could work through the organizational network to reach the members of a large number of churches. The letter put the research in a context that made it not only acceptable and important but provided another opportunity for action in faith. It is possible that this helped survivors who chose to participate see their research participation not as a luxury but as a fit with their faith as well as their care.

Traditional racial and ethnic barriers have been well discussed [2, 7, 23, 27], as has the importance of community engagement in research [5, 6, 28, 29]. There is also some literature on the difficulty of recruiting and retaining people with certain demographic characteristics like older age, low education levels, and low income [3, 8]. Building on this literature and our team’s prior experience in five intervention trials, we found that it was important to use a multifaceted approach which combined knowledge of racial/ethnic barriers to research participation; cultural themes; the need to bridge gaps across cultures and communities; principles of community based and community based participatory research, the role of faith and beliefs in considering research participation; the demands of different life stages and economic situations; the busy pace of these women’s lives; and the place of research in the larger picture of survivors’ lives. Among the many lessons learned by our research team, the most important was that successful recruitment of survivors of any race/ethnicity is much more complex than indicated by the literature on barriers to recruitment of minorities [30, 31]. For instance, using a multifaceted approach involves non-random community based approaches, which raises questions about the extent to which participants are demographically representative of the target community [32].

This paper describes a recruitment and retention program that was not only culturally informed and responsive to the particular circumstances of a diverse sample of younger breast cancer survivors, but also engaged community partners. Like this program, designs for recruitment and retention need to be broadly conceptualized and specifically applied, using a variety of well grounded strategies.

Limitations

The culturally informed, responsive, community focused approaches here were based on literature describing barriers to research participation for AAs and built on successful strategies described by other investigators, and on the community experience of our partners. While we used the literature to derive a multifaceted approach to recruitment and retention of AA breast cancer survivors, this approach was not developed a priori but evolved over the time of the trial. We did not use a comprehensive community based participative research model. Although our results were very successful, the replication and systematic testing of strategies is needed in order to know which aspects of the approach were most effective in the successful recruitment and retention rates for this population of younger breast cancer survivors.

Implications for survivors

For busy younger breast cancer survivors, the demands of work, school, immediate and extended family, financial obligations and self-care may make research participation a low priority as they move from their cancer experiences back to the rest of their lives. If these survivors are also AA, historical and cultural issues may be additional barriers to their involvement in research. The development and application of knowledge related to survivors is crucially informed by the diversity of those participants involved and the representativeness of samples recruited. The willingness of younger AA breast cancer survivors to participate in and complete research participation is enhanced by strategies that address barriers but also acknowledge and respect the many demands on their time by making research familiar, available, accessible and credible.

Acknowledgments

The research described here was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute for Nursing Research, entitled Younger Breast Cancer Survivors: Managing Uncertainty (5R01NR010190; PI: M. Mishel). Supplemental funding was obtained from the School of Nursing, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Faculty Research Opportunity Grants Program.

Dr. Vines’s and D. Long’s efforts were supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities through its Community Networks Program (#U01CA114629).

We gratefully acknowledge the community partners and cultural brokers who enabled the successful recruitment and the willingness of our participants to share their time to enable this trial.

Insert A: Letter to United Methodist Bishops

Greetings in the name of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ

I am a United Methodist, I am African American and I am a nurse researcher who has joined devoted colleagues in studying breast cancer and we need your help. You and I are partners in ministry even though our ways and means of reaching God’s children take different approaches. We both have the desire to help the world family live the best life possible. This includes talking and teaching about matters of health. This is also in keeping with scripture which states that our bodies are our temples and we are to take care of the body so that we are able to fulfill our purpose and do God’s will. For a healthy congregation is a wealthy congregation.

More than likely in your role as a pastor serving and loving members of your congregations you have had an experience with breast cancer in a personal way. Perhaps it was a mother, grandmother, sister, cousin, child, spouse, a good friend, a choir member or another female clergy member who was diagnosed and treated. Prayer and the sharing of information are means of intercession. Both acts honor John Wesley’s request of United Methodists to do all we can, in all the ways we can, for as many as we can. Therefore, I am asking that you join us in ministry by helping us to disseminate information about our research study to African American women and those who know African American women. So far our efforts to gain their participation have led to modest gains.

Participants in The Younger Breast Cancer Survivors: Managing Uncertainty study will be given assistance in managing the uncertainties of living as a breast cancer survivor. We will do all the work and put together information that could be included in newsletters, church bulletins and in health fairs. Members of the study would also be willing to make brief (5 min) presentations either right before or immediately following worship services, work with your Health and Welfare committee, Black Methodist for Church Renewal Committee, the Ethnic Minority Local Church committee or other appropriate gatherings to share information about the study and answer questions. We simply ask for your leadership in the dissemination of information by a means of convenience to you.

On page 2 of this letter, we have provided more detailed information regarding who is eligible to participate and what they will be asked to do as participants in the study. If you are willing to partner in ministry with us, let me know so that we can begin to make arrangements for the dissemination of the materials (see contact information below). Each participating church will need to identify a contact person or church representative who would serve as a link between the church parishioners and the study personnel.

Thank you so much for any assistance you may be able to provide. Sharing information with your congregants affords them the opportunity to make a difference in not only their lives but the lives of others United Methodists throughout the connection will benefit.

Contact Information

Dr. _____

Email_____

Phone: _____

Peace and Health,

__________-

Contributor Information

Barbara B. Germino, Email: germino@email.unc.edu, School of Nursing, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB# 7460, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA

Merle H. Mishel, School of Nursing, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB# 7460, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA

G. Rumay Alexander, Office of Multicultural Affairs, School of Nursing, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB# 7460, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Coretta Jenerette, School of Nursing, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB# 7460, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Diane Blyler, School of Nursing, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB# 7460, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Carol Baker, School of Nursing, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB# 7460, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Anissa I. Vines, UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB# 7435, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Melissa Green, Project CONNECT, Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB# 7590, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Debra G. Long, CrossWorks, Inc., Rocky Mount, NC, USA

References

- 1.Mak WW, Law RW, Alvidrez J, Perez-Stable EJ. Gender and ethnic diversity in NIMH-funded clinical trials: review of a decade of published research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34(6):497–503. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0133-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russell KM, Maraj MS, Wilson LR, Shedd-Steele R, Champion VL. Barriers to recruiting urban African American women into research studies in community settings. Appl Nurs Res. 2008;21 (2):90–7. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilcox S, Shumaker SA, Bowen DJ, Naughton MJ, Rosal MC, Ludlam SE, et al. Promoting adherence and retention to clinical trials in special populations: a women’s health initiative workshop. Control Clin Trials. 2001;22(3):279–89. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cross TL. Towards a culturally competent system of care: a monograph on effective services for minority children who are severely emotionally disturbed. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Child Development Center, CASSP Technical Assistance Center; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horowitz CR, Arniella A, James S, Bickell NA. Using community-based participatory research to reduce health disparities in East and Central Harlem. Mt Sinai J Med. 2004;71(6):368–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandra A, Paul DP., III African American participation in clinical trials: recruitment difficulties and potential remedies. Hosp Top. 2003;81(2):33–8. doi: 10.1080/00185860309598020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coatsworth J, Duncan L, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. Patterns of retention in a preventive intervention with ethnic minority families. J Prim Prev. 2006;27(2):171–93. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-0028-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dilworth-Anderson P, Burton LM. Rethinking family development. J Soc Pers Relatsh. 1996;13(3):325–34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton JB, Sandelowski M. Living the golden rule: reciprocal exchanges among African Americans with cancer. Qual Health Res. 2003;13(5):656–74. doi: 10.1177/1049732303013005005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAdoo HP. Upward mobility and parenting in middle-income Black families. In: Burlew AKMH, Banks WC, McAdoo HP, ya Azibo DA, editors. African American psychology: theory, research and practice. Newbury Park: Sage; 1992. pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sue DW, Capodilup CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder AMB, Nadal KL, et al. Racial microaggressions in everyday life. Am Psychol. 2007;62(4):271–86. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dilworth-Anderson P, Thaker S, Burke JMD. Recruitment strategies for studying dementia in later life among diverse cultural groups. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2005;19(4):256–60. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000190803.11340.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powe BD. Cancer fatalism among African-Americans: a review of the literature. Nurs Outlook. 1996;44(1):18–20. doi: 10.1016/s0029-6554(96)80020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powe BD, Hamilton J, Brooks P. Perceptions of cancer fatalism and cancer knowledge—a comparison of older and younger African American women. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2006;24(4):1–13. doi: 10.1300/J077v24n04_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holt CL, Lukwago SN, Kreuter MW. Spirituality, breast cancer beliefs and mammography utilization among urban African American women. J Health Psychol. 2003;8(3):383–96. doi: 10.1177/13591053030083008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grange CM, Matsuyama RK, Ingram KM, Lyckholm LJ, Smith TJ. Identifying supportive and unsupportive responses of others: perspectives of African American and Caucasian cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2008;26(1):81–99. doi: 10.1300/j077v26n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strayhorn G. Faith-based initiatives. In: Satcher D, Pamies RJ, editors. Multicultural medicine and health disparities. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2006. pp. 495–507. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St George DMM. Distrust, race, and research. Arch Intern Med. 2002;62(21):2458–63. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dula A. African American suspicion of the healthcare system is justified: what do we do about it? Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 1994;3 (3):347–57. doi: 10.1017/s0963180100005168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Earl CE, Penney PJ. The significance of trust in the research consent process with African Americans. West J Nurs Res. 2001;23(7):753–62. doi: 10.1177/01939450122045528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freimuth VS, Quinn SC, Thomas SB, Cole G, Zook E, Duncan T. African Americans’ views on research and the Tuskegee syphilis study. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(5):797–808. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Racial differences in factors that influence the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12(4):248–56. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein S. The rise of ‘recruitmentology’: clinical research, racial knowledge, and the politics of inclusion and difference. Soc Stud Sci. 2008;38(5):801–32. doi: 10.1177/0306312708091930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stark N, Paskett E, Bell R, Cooper MR, Walker E, Wilson A, et al. Increasing participation of minorities in cancer clinical trials: summary of the “moving beyond the barriers” conference in North Carolina. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(1):31–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Center for Cultural Competence. Guide developed for the National Health Service Corps. Bureau of Health Professions, Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services; 2004. Bridging the cultural divide in health care settings: the essential role of cultural broker programs; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, Gary TL, Bolen S, Gibbons MC, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112 (2):228–42. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dancy BL, Wilbur JE, TAAshek M, Bonner G, Barnes-Boyd C. Community-based research: barriers to recruitment of African Americans. Nurs Outlook. 2004;52(5):234–40. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staffileno BA, Coke LA. Recruiting and retaining young, sedentary, hypertension-prone African American women in a physical activity intervention study. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006;21 (3):208–16. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200605000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janson SL, Alioto ME, Boushey HA. Attrition and retention of ethnically diverse participants in a multicenter randomized controlled research trial. Control Clin Trials. 2001;22(6 Suppl):236S–43S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(01)00171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson JM, Trochim WM. An examination of community members’, researchers’ and health professionals’ perceptions of barriers to minority participation in medical research: an application of concept mapping. Ethn Health. 2007;12(5):521–39. doi: 10.1080/13557850701616987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halbert GH, Kumanyika S, Bowman M, Bellamy SL, Briggs V, Brown S, et al. Participation rates and representativeness of African Americans recruited to a health promotion program. Health Educ Res. 2010;25(1):6–13. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]