Abstract

Introduction

The small bones and soft tissues of the hands and feet can be affected by systemic disorders, and frequently, the findings are quite unique and virtually diagnostic for some genetic or metabolic disorders.

Materials and Methods

Photographs and imaging studies for the hands and feet are available in a digitized system, which has been approved by our hospital institutional review board. Examination of these and their description can establish a relationship with some degree of certainty to a series of highly variable and uncommon clinical disorders.

Results

Description of the clinical, physiologic and genetic characteristics, and illustrations of hand and foot abnormalities are provided for an array of diseases, including Ellis–van Creveld syndrome, fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, achondroplasia, Kniest dysplasia, pseudo- and pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism, acromegaly, nail–patella syndrome, Marfan’s disease, cartilage–hair hypoplasia, and several forms of mucopolysaccharidosis.

Conclusions

The findings support the concept that many genetic disorders can often be diagnosed by clinical and imaging examination of the patient’s hands and feet.

Keywords: Ellis–van Creveld syndrome, Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, Achondroplasia, Kniest dysplasia, Pseudohypoparathyroidism, Acromegaly, Nail–patella syndrome, Marfan syndrome, Mucopolysaccharidosis, Cartilage–hair hypoplasia

Introduction

There is little doubt that the small bones and soft tissues of the hands and feet can be affected by systemic disorders, and frequently, the findings are quite unique and virtually diagnostic. Caretakers for patients with these problems usually depend on physical examination of the patient, imaging studies, and laboratory tests to help make diagnoses for many of the genetic or metabolic disorders, but sometimes the changes in the structural bones of hand or foot, metacarpals and metatarsals, or the phalangeal units are so remarkable as to lead to the diagnosis for sometimes puzzling or confusing syndromes. We have included illustrations of these entities which we believe are useful in identifying the cause. Included in the list of genetic disturbances with quite specific and often diagnostic hand and foot alterations are Ellis–van Creveld syndrome, fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, achondroplasia, Kniest dysplasia, pseudo- and pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism, acromegaly, nail–patella syndrome, Marfan’s disease, cartilage–hair hypoplasia, and several forms of mucopolysaccharidosis.

The Disorders

Ellis–van Creveld syndrome was first described in 1940 by two physicians, one British and the other Dutch, who met on a train going to a pediatric society meeting and discovered that they had both seen cases of a very rare disorder. They published their reports regarding the two patients and named the disease chondroectodermal dysplasia based on the extraordinary features [37]. The disorder has some unusual characteristics, including shortness of stature, irregular bone growth and structure, and some remarkable oral findings, including strange teeth and lip ties [20, 53, 75, 87]. The chromosomal site for the genetic error in patients with Ellis–van Creveld syndrome is at 4p16 [39, 75]. The entity is a very rare autosomal recessive disorder but occurs with greatest frequency in Amish people [74].

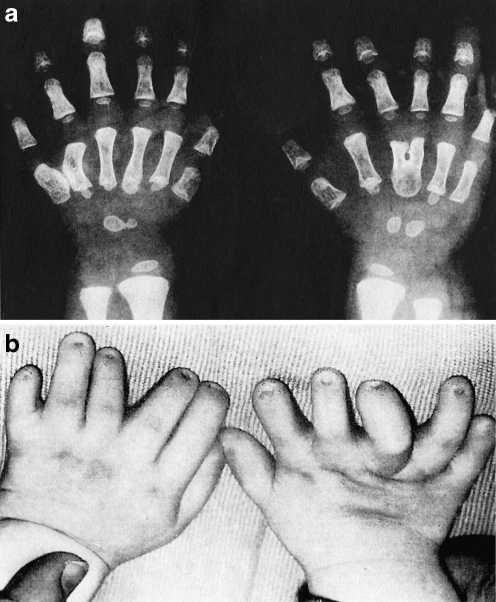

Hand Abnormalities The most remarkable clinical feature of the Ellis–van Creveld syndrome is polydactyly, the presence of a sixth digit on the ulnar sides of the hands and less frequently, the fibular sides of the feet (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

a X-ray and photograph of the hands of a child with Ellis–van Creveld syndrome. b Note the polydactyly with an extra small digit on the ulnar side. Several other digits are distorted and the third and fourth metatarsals on the right side are fused. There is also curvature of the fifth metatarsal on the left side

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva is a rare genetic disorder in which the fibrous tissues, muscles, and periosteal regions undergo progressive ossification [12, 30, 32, 89]. As a result, beginning at approximately age 5, the patient develops sometimes massive ectopic osseous collections in the muscular regions adjacent to the bones and joints and most often becomes extraordinarily disabled by the limitation of movement of joints and alterations in osseous structure [32, 49, 85]. The nature of this strange genetic disorder is the presence of abnormal heterotopic ossification of the muscle, fascia, and periosteum which appears to be caused by a dysregulation of cell differentiation [30, 56, 89]. As stated by Kaplan, “normal bone forms in the wrong place at the wrong time” [57]. The disease appears to be genetic and is transmitted as an autosomal dominant disorder but with frequent mutations in relation to chromosomes 4q27-31, 17q21-22, or 2q23-q24 [57, 89].

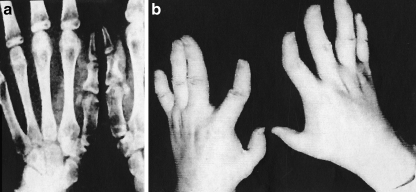

Hand Abnormalities One of the most extraordinary and consistent clinical features is not related to increased bone formation in the soft tissues. Instead, it consists of shortening and deformity of the great toes and sometimes of the thumbs. This is believed to be a separate genetic entity but of similar origin and frequency (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

a Hands of a patient with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. b The hands like the rest of the body may show production of new bone adjacent to the skeletal segments but there is a striking shortening and deformity of the thumbs

Achondroplasia is a genetic disorder transmitted as an autosomal dominant error with frequent mutations. Recent studies of the gene structure in patients with achondroplasia strongly support the concept that the error lies with a mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3, which is a membrane-spanning tyrosine kinase receptor with three domains, which exerts a negative control on growth of connective tissue components [24, 52, 82]. The disease is frequent in siblings and is believed to occur in the United States at a rate of one in every eight to10,000 births. Patients with achondroplasia have normal intelligence, short stature, rhizomelic shortening and wide epiphyses of the long bones, frontal bossing, midface hypoplasia, narrowing of the foramen magnum, spinal stenosis, diminished size of the innominate bone, thickening of the ribs, lumbar lordosis, thoracic kyphosis, elbow limitation, and a very unusual entity…the “trident hand deformity”[8, 47, 58, 78].

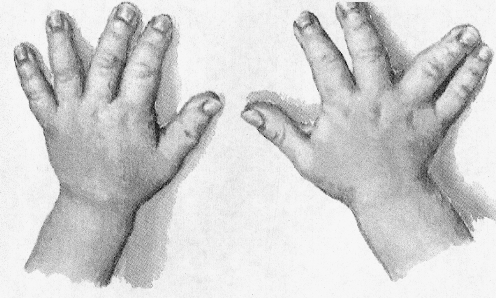

Hand and Foot Abnormalities Patients with the trident hand deformity are often unable to approximate full extension of their fingers, and the middle finger is often reduced in length. Hand X-rays frequently show shortening of the third metacarpal and imaging of the ankles may disclose relative elongation of the fibula, causing a varus deformity of the foot (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Hands of a child with achondroplasia showing the characteristic “trident hand.” The third metacarpal is short, the fourth deviated to the ulnar side, and the thumb is radially displaced

Kniest dysplasia is an autosomal dominant genetic error which, for the most part, is equally divided amongst males and females except for a small number of male patients who seem to have an X-linked gene error [23, 85, 88]. The gene error principally affects the synthesis and maintenance of type II collagen and far less commonly, type XI collagen [29, 81]. Type II is principally located in the articular and epiphyseal cartilages so that the effect is damage to these structures, principally in bone formation in the fetus or infant. The disorder results in the changes in the shape and structure of long bones, small bones of the hands and feet, ribs, and especially the spine [62, 81]. Growth is slowed and the cartilage forming structures are deformed as a result of the “Swiss cheese cartilage” changes and substitution by other forms of cartilage [38, 40]. Disproportionate dwarfism (the limbs are more severely affected than the trunk) cause sometimes severe kyphoscoliosis and lumbar lordosis, short and bell-shaped thorax, flat facies, prominent forehead and wide-set eyes, cleft palate, otitis media, hearing loss, proptosis, and severe myopia, which can lead to retinal detachment and early cataract development [18, 22, 29]. The long bones are short and bowed and the joints are moderately enlarged [18, 29, 69, 81].

Hand and Foot Abnormalities The hands are almost always abnormal with long knobby fingers, which make it difficult for the patient to form a fist. X-rays show flattening and squaring off of the epiphyses of tubular bones of the hands and feet (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Hands of a child with Kniest disease. Not the long knobby fingers and the “squared off epiphyses” for the digits as well as the distal radius and ulna

Pseudo- and pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism are complex entities. There are four small parathyroid glands located on the posterior aspect of the thyroid gland. The cells in these glands are responsible for the production of parathyroid hormone (PTH), a single-chain protein containing 84 amino acids [44, 64]. The material is released from the cell in response to a G protein-coupled calcium-sensing receptor, which is activated by a reduction in serum calcium concentration. The chemical actions of PTH are to increase the serum calcium and reduce the serum phosphate. The osseous action is to reduce the amount of bony substance principally by osteoclastic bone destruction [44]. The earliest recognition of the pseudo- and pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroid disorders was by Albright who named them hereditary osteodystrophy or the Seabright-Bantam syndrome [3, 4]. In his original contribution in 1942, he identified the clinical characteristics and also indicated that the patients have normal parathyroid glands. The two forms pseudo- and pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism are closely tied together. Both lesions are genetic in origin and the patients have normal parathyroid glands and PTH production but display a remarkable target tissue unresponsiveness, which results in a failure of the normal action of autogenous or administered PTH on the bone or kidney. Patients may show resistance to not only PTH, but also thyroid stimulating hormone, gonadotropins, and glucagons [64, 85]. Cellular elements from these patients show an approximately 50% reduction in expression of G2α protein, which impairs the ability of the PTH to activate adenyl cyclase. In addition, there are some systemic findings, sometimes quite dramatic and disabling, seen in association with these syndromes. These include short stature, round facies, obesity, subcutaneous ossification, and mental retardation [1, 3, 34, 64, 66].

Hand and Foot Abnormalities In patients with these disorders, the fourth and fifth metatarsal and metacarpal bones are often quite short. Less commonly, the third is also affected. Imaging studies of the hands and feet often show rather remarkable and almost diagnostic changes in the third, fourth, and fifth metacarpals and metatarsals which may be almost half the size of the adjacent, more normal bones (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Classic changes of the hand bones in a patient with pseudohypoparathyroidism. The changes are identical for patients with pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. The fourth and fifth digits are short and are often half the size of the adjacent digits

Acromegaly. Despite diverse histologic abnormalities, excessive production of growth hormone (GH) is the factor which causes both childhood gigantism and late in adulthood acromegaly [5]. Normally, the hypothalamus releases a material known as growth hormone releasing hormone, which causes the pituitary gland to increase the level of GH production [5, 13]. In turn, GH activates elevated levels of liver insulin growth factor-I otherwise known as somatomedin C, which is responsible for the growth of organs including bones [5, 19, 26, 27]. There are two principal presentations for acromegaly: gigantism in children and acromegalic changes in adults with late onset disease [10, 65]. Adult acromegaly is more common and at times much more severe than pituitary gigantism and occurs equally in males or females. The disorder may be present for years prior to discovery, which often occurs in middle age. Increased body hair is often noted [21, 65]. Colon polyps are common and occasional colon cancer has been described [27, 28]. The patients often complain of increased sweating. The ribs are often enlarged particularly at the sites of the costochondral junctions. Scoliosis and abnormal vertebral structure are commonly present. Studies of the skull may show damage to the sella turcica caused by enlargement of the pituitary adenoma and sometimes marked enlargement of the mandible [10, 61, 65, 96]. Malformation of the teeth is a common finding [65].

Hand and Foot Abnormalities The patients with this disorder develop sponginess and puffiness of hands and feet and this is particularly evident in the heel pads. This finding can be made by clinical examination or by imaging studies and is quite distinctive (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Acromegaly produces striking changes in the soft tissues of the hands. Note the sponginess and puffiness of the hands and the peculiar small red spots in the skin. Compare the skin features with the normal hand included in the picture

Nail–patella syndrome is familial and is transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait with a high degree of penetrance but variable expression [11, 46, 54]. The chromosomal location for the error has been identified as the long arm of chromosome 9 (9q34.1) and the disorder appears to be caused by mutations in transcription factor LMX1B [11, 16, 17, 35, 36, 73, 84]. Patients with the nail–patella syndrome most frequently have a lean body habitus and have difficulty putting on weight despite increased dietary intake [16]. In many patients, there is a fairly marked decrease in muscle mass in the proximal upper and lower extremities. The biceps and triceps and the quadriceps and gluteal muscles may be markedly diminished in size while the forearm and leg musculature appears normal [68]. Nails are absent or deformed [39, 49, 57, 86]. Lumbar lordosis is frequently present. The forehead is high and the hairline appears to be receding even in young children or women. The patellae may be absent or very small in size and laterally displaced [72]. The result for the knees is one of knock-knee deformity and sometimes limitation of movement and osteoarthritic changes with advancing age [46]. One of the most striking features of the disorder is the presence of iliac horns. These are bilateral conical bony processes that project posteriorly and laterally from the center of the ilium [45, 46, 83].

Hand and Foot Abnormalities In the affected patient, nails may be absent or hypoplastic or dystrophic. They are sometimes ridged longitudinally or horizontally or pitted or even separated into two halves by a cleft or a ridge of skin. The thumbnails are the most severely affected. The changes may show as triangular lunules. As a rule, the changes in the toenails are less marked. The skin over the distal phalanges shows a loss of creases, particularly over the index fingers. The hand may show a diminished capacity for flexion or hyperextension of the joints, which may produce a characteristic “swan-neck deformity” and a mild functional impairment (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Changes in the nails of the fingers of a patient with nail–patella syndrome. The nails are almost completely absent or markedly ridged and abnormally structured. The skin shows a loss of creases

Marfan syndrome is an inherited connective tissue disorder transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait with frequent mutations. The disorder is equally distributed in ethnic groups and is slightly more frequent in females than males. The disorder is now known to be caused by mutations in the fibrillin-1 gene located on chromosome 15q21.1, which is a major building block for microfibrils, including those involved in the skeletal system, the spinal dura, the optic lens supporting system, and the elastin in the aorta and cardiac valvular structures [14, 55, 71]. Children born with Marfan syndrome are often quite tall and in a short time are taller than their normal siblings and peers [55, 80]. Some of the patients as adults may grow to over 7 ft in height. Eye problems may be present [71]. Spinal disorders are frequent and sometimes disabling [2]. An important finding is dolichostenomelia, which is defined as having excessively long limbs [42, 55]. The bones are generally osteopenic with frequent fractures and with an unusually frequent occurrence of protrusio acetabulae which can be very disabling [42, 55, 91].

Hand and Foot Abnormalities The hands and feet in patients with Marfan syndrome show very thin and much elongated digits which are described as “arachnodactyly,” suggesting that they resemble the limbs of spiders. The great toe is sometimes markedly elongated. The hand digits are excessively mobile and the flexed thumb may extend beyond the four fingers when the hand and digits are flexed (Steinberg thumb sign). In addition, the combination of a thin wrist and long digits may allow an overlap of the thumb and first and fifth fingers when the wrist is grasped (Walker–Murdoch sign) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Classic changes in the hand of a patient with Marfan’s syndrome. The digits are markedly elongated and the digital structure is distorted. The distal radius and ulna region show a V-shaped deformity which leads to the deviation and further limitation of function of the hand

The mucopolysaccharidosis types I-S, I-M, II, IV, VI (Hurler, Scheie, Hunter, Morquio, and Maroteaux–Lamy syndromes) are rare disorders resulting from autosomal recessive genetic errors [92–94]. The entities are broadly classified as lysosomal storage diseases and are caused by enzyme deficiencies, which result in a failure to degrade the glycosaminoglycans, chondroitin sulfate, dermatan sulfate, and heparan sulfate [7, 92–94] The presence of excessive amounts of the glycosaminoglycans cause neurologic, ocular, skeletal, pulmonary, and cardiac abnormalities which may be so severe as to be recognizable shortly after birth and can cause the early demise of a child [25, 33, 63]. Affected children are often dwarfed and some have progressive mental deterioration, most often in association with hydrocephalus [76, 77, 85]. The craniofacial appearances are quite striking [27, 81]. The children have large heads with mask-like facies [81]. The hair on their heads and eyebrows is coarse, bristly, and straight [81, 82]. The nose is flat and wide and the nares are large and upturned. The eyes may have significant problems [6, 81, 82].The ears are large with thick lobes. The lips are patulous, considerably larger than normal and the tongue protrudes. The teeth are late to erupt and may be small and malformed [77, 80, 85]. Widening of the anterior and lateral ribs with narrowing of the posterior portions is frequently present and the chest contours are often quite irregular [70, 80, 93]. The vertebral segments are usually ovoid in shape with wedge-shaped vertebrae at T12 or L1, which is the cause of the malformed shortened spine and gibbus formation [9, 59, 76, 77]. Carpal tunnel syndrome is common [41, 97].

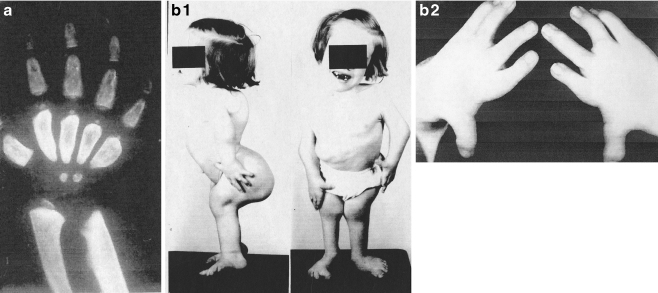

Hand and Foot Abnormalities For all of the four forms of these disorders, the phalanges are wide and are proximally pointed and for some forms, there is a V-shaped deformity of the distal radius and ulna based on oblique deformity of both bones at their terminal ends. The digits usually fail to completely extend causing a “claw hand,” and carpal tunnel syndrome is a frequent finding. The subcutaneous tissues on the surface of the hands are thickened, contributing to the poor function of the digits (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Almost all forms of the mucopolysaccharidoses show gross distortion of the hand and foot structure. a Shows a child with Hurler syndrome with hepatosplenic enlargement. Note the hand flexion deformities. As noted in the X-ray, the metacarpals and phalanges are wide and the distal radius and ulna have a V-shaped deformity. The child is severely mentally impaired. b (1) A photograph of a child with Morquio’s syndrome. She is short and grossly deformed but mentally normal. (2)Her hands and feet show gross digital distortion

Cartilage–hair hypoplasia was first described by Victor McKusick in 1964 and is a rare disorder in most populations but has increased frequency in Finnish and Old Order Amish persons [67, 95]. The disorder is characterized by short stature, very thin colorless hair, and bone deformities, especially of the spine, lower extremities, and hands. The patients are not mentally retarded, but some of them have a frightening array of complications, including immune deficiencies, anemia and leukopenia, cancers, and increased mortality [48, 95]. The disorder appears to occur in relation to chromosome 9 and is believed to result from mutations in RNase mitochondrial RNA processing (RMRP), a material required for cell growth [90]. Alteration in RMRP causes defects in cell growth of T cells, B cells, and fibroblasts and impairment of ribosomal assembly [15, 50, 51, 60, 79]. Histologic studies of the epiphyseal plates show abnormal cartilage structure with a reduction in the height and, sometimes, marked irregularity of the columns. Examination of hair fibers from the scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes of patients with the syndrome display an extraordinarily thin caliber and lack a central core [31]. Affected children have thin brownish hair and almost always display a substantial reduction in height, which has been described as short-limb dwarfism [43, 48, 68]. The vertebrae are small and have mild irregularity at the end plates [68]. Scoliosis and lordosis are commonly seen [43, 67, 68, 72].

Hand and Foot Abnormalities The hands and feet are “pudgy” and the skin hypopigmented. The hands are short and the fingers are frequently bent but can be easily extended. The nails show foreshortening and a mild dysplasia. X-rays show shortening of the metacarpals, metatarsals, and phalanges (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

The hands of children with cartilage–hair hypoplasia show skin and structural alterations consisting principally of short digits often bent. The metacarpals are short, and the carpal bone are poorly structured and calcified

Discussion

There are many additional disorders, some genetic, some neoplastic, some inflammatory which produce sometimes extraordinary changes in the patient’s hands and feet. A brief, incomplete listing includes tumoral calcinosis, Ollier’s disease, Maffucci syndrome, hereditary multiple osteocartilaginous exostosis, type 1 neurofibromatosis, pigmented villonodular synovitis, synovial chondromatosis, hyperparathyroidism, gout, and fibrous dysplasia. These disorders are much more common than those in this series and the findings more easily identified and treatment protocols well understood.

Nevertheless, the collection of 10 diseases in this review is quite remarkable. Patients with these quite rare genetic disorders have multiple and quite variable abnormalities affecting their mental, neurologic, vascular, gastrointestinal, ophthalmologic, cardiac, pulmonary, osseous, and articular tissues but in addition have quite distinctive and clinically characteristic disorders affecting their hands and feet. The implication is that the various and distinct gene errors not only affect the major body systems described above but remarkably also specifically affect the structure and function of the hands and feet. Furthermore, in many of the disorders, the systemic findings may vary considerably from patient to patient while the hand and foot changes are present and quite uniquely distinctive. This may be why the diagnosis of the entity may be in large measure supported and indeed defined by the hand and foot problems rather than the changes in other body structures. Of some note, however, the author suggests that the most important and rewarding aspect of this study has been the quite fascinating definition of a series of acral alterations related to diseases very rarely seen in the practice of orthopedics.

References

- 1.Agarwal C, Seigle R, Agarwal S, et al. Pseudohypoparathyroidism: a rare cause of bilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr. 2006;149:406–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn NU, Sponseller PD, Ahn UM, et al. Dural ectasia is associated with back pain in Marfan syndrome. Spine. 2000;25:1562–1568. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200006150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albright F, Burnett CH, Smith PH. Pseudohypoparathyroidism: an example of “Seabright-Bantam syndrome”. Endocrinology. 1942;30:922–932. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albright F, Forbes AP, Henneman PH. Pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1952;65:337–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asa SL, Ezzat S. Genetics and proteomics of pituitary tumors. Endocr. 2005;28:43–47. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:28:1:043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashworth JL, Biswas S, Wraith E, Lloyd IC. Mucopolysaccharidoses and the eye. Surv Opthalmol. 2006;51:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bach G, Friedman R, Weissman B, Neufield EF. The defect in the Hurler and Scheie syndromes: deficiency of alpha-l-iduronidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:2048–2051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.8.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey JA., II Orthopaedic aspects of achondroplasia. J Bone Jt Surg. 1970;52A:1285–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banna M. Compressive meningeal hypertrophy in mucopolysaccharidoses. Am J Neuroradiol. 1987;8:385–386. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barkan AL. Acromegaly: diagnosis and therapy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1989;18:277–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beguinstain JL, Rada PD, Barriga A. Nail–patella syndrome: long-term evolution. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2003;12:13–16. doi: 10.1097/00009957-200301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beighton P. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. In: Beighton P, editor. McKusick’s heritable disorders of connective tissue. 5. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993. pp. 501–518. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Besser GM, Mortimer CH, Carr D, et al. Growth hormone release inhibiting hormone in acromegaly. Br Med J. 1974;1:352–355. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5904.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boileau C, Jondeau G, Mizuguchi T, Matsumoto N. Molecular genetics of Marfan syndrome. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2005;20:194–200. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000162398.21972.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonafe L, Schmitt K, Eich G, et al. RMRP gene sequence analysis confirms a cartilage–hair variant with only skeletal manifestations and reveals a high density of single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Clin Genet. 2002;61:146–151. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.610210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bongers EM, Gubler MC, Knoers NV. Nail–patella syndrome. Overview on clinical and molecular findings. Pediatr Nephrol. 2002;17:703–712. doi: 10.1007/s00467-002-0911-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bongers EM, Huysmans FT, Levtchenko E, et al. Genotype–phenotype studies in nail patella syndrome show that LMX1B mutation location is involved in the risk of developing nephropathy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13:935–946. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brill PW, Kim HJ, Beratts NG, Hirschhorn K. Skeletal abnormalities in the Kniest syndrome with mucopolysacchariduria. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;125:731–738. doi: 10.2214/ajr.125.3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brooke AM, Drake WM. Serum IGF-I levels in the diagnosis and monitoring of acromegaly. Pituitary. 2007;10:173–179. doi: 10.1007/s11102-007-0036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cahuana A, Palma C, Gonzales W, Gean E. Oral manifestations in Ellis–van Creveld syndrome: report of five cases. Pediatr Dent. 2004;26:277–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centurion SA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous signs of acromegaly. J Dermatol. 2002;41:631–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chalam KV, Tripathi RC, Tripathi BJ, et al. Cataract in Kniest dysplasia: clinicopathologic correlation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:913–915. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.6.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen L, Yang W, Cole WG. Alternative splicing of exon 12 of the COL2A1 gene interrupts the triple helix of type–II collagen in the Kniest form of spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia. J Orthop Res. 1996;14:712–721. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100140506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho JY, Guo C, Torello M, et al. Defective lysosomal targeting of activated fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 in achondroplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:609–614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237184100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleary MA, Wraith JE. The presenting features of mucopolysaccharidosis type IH (Hurler Syndrome) Acta Paediatr. 1995;84:337–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1995.tb13640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clemmons DR. Quantitative measurement of IGF-I and its use in diagnosing and monitoring treatment of disorders of growth hormone secretion. Endocr Dev. 2005;9:55–65. doi: 10.1159/000085756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colao A, Ferone D, Marzullo P, Lombardi G. Systemic complications of acromegaly: epidemiology, pathogenesis and management. Endocrinol Rev. 2004;25:102–152. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colao A, Pivonello R, Marzullo P, et al. Severe systemic complications of acromegaly. Endocrinol Invest. 2005;28(5 Suppl):65–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cole WG. Abnormal skeletal growth in Kniest dysplasia caused by type II collagen mutations. Clin Orthop. 1997;341:182–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connor JM, Evans DA. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: clinical features and natural history of 34 patients. J Bone Jt Surg. 1982;64:76–83. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.64B1.7068725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coupe RL, Lowry RB. Abnormality of the hair in cartilage–hair hypoplasia. Dermatologica. 1970;141:329–334. doi: 10.1159/000252497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cremin B, Connor JM, Beighton P. The radiological spectrum of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressive. Clin Radiol. 1982;33:499–508. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(82)80159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dangel JH. Cardiovascular changes in children with mucopolysaccharide storage diseases and related disorders—clinical and echocardiographic changes in 64 patients. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157:534–538. doi: 10.1007/s004310050872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanctis L, Vai S, Andreo MR, et al. Brachydactyly in 14 genetically characterized pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ia patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1650–1655. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dreyer SD, Zhou G, Baldini A, et al. Mutations in LMX1B cause abnormal skeletal patterning and renal dysplasia in nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19:47–50. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunston JA, Lin S, Park JW. Phenotype severity and genetic variation at the disease locus: an investigation of nail dysplasia in the nail patella syndrome. Ann Hum Genet. 2005;69:1–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ellis RW, van Creveld S: A syndrome characterized by ectodermal dysplasia, polydactyly, chondrodysplasia and congenital morbus cordis. Report of three cases. Arch Dis Child. 1940. pp 15–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Fernandes RK, Wilkin DJ, Weis MA, et al. Incorporation of structurally defective type II collagen into cartilage matrix in Kniest chondrodysplasia. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;355:282–290. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Francomano CA, Ortez De Luna RI, Ide SE, et al. The gene for the Ellis–van Creveld syndrome maps to chromosome 4p16. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:a191. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frayha R, Melhern R, Idriss H. The Kniest (Swiss cheese cartilage) syndrome. Description of a distinct arthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1979;22:286–289. doi: 10.1002/art.1780220312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geschwind C, Tonki MA. Carpal tunnel syndrome in children with mucopolysaccharidosis and related disorders. J Hand Surg. 1992;17A:44–47. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(92)90111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giampietro PF, Peterson M, Schneider R, et al. Assessment of bone mineral density in adults and children with Marfan syndrome. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:559–563. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glass RBJ, Tifft CJ. Radiologic changes in infancy in McKusick cartilage hair hypoplasia. Am J Med Genet. 1999;86:312–315. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19991008)86:4<312::AID-AJMG2>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goltzman D, Cole DEC. Hypoparathyroidism. In: Favus MJ, editor. Primer on the metabolic bone diseases and disorders of mineral metabolism. 4. Philadelphia: William and Wilkins; 1999. pp. 226–230. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goshen E, Schwartz A, Zilka LR, Zwan ST. Bilateral accessory iliac horns. Pathognomonic findings in nail–patella syndrome. Scintigraphic evidence on bone scan. Clin Nucl Med. 2000;25:476–477. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200006000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guidera KJ, Satterwhite Y, Ogden JA, et al. Nail patella syndrome: a review of 44 orthopaedic patients. J Pediatr Orthop. 1991;11:737–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hall JG. The natural history of achondroplasia. Basic Life Sci. 1988;48:3–9. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-8712-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Halle MA, Collipp PJ, Roginsky M. Cartilage–hair hypoplasia in childhood. New York J Med. 1970;70:2705–2708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harrison RJ, Pitcher JD, Mizel MS, et al. The radiographic morphology of foot deformities in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:937–941. doi: 10.1177/107110070502601107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hermanns P, Bertuch AA, Bertin TK, et al. Consequences of mutations in the noncoding RMRP RNA in cartilage–hair hypoplasia. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3723–3740. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hirose Y, Nakashima E, Obashi H, et al. Identification of novel RMRP mutations and specific founder haplotypes in Japanese patients with cartilage–hair hypoplasia. J Hum Genet. 2006;51:706–710. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horton WA. Recent milestones in achondroplastic research. Am J Med Genet. 2006;140A:166–169. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Howard TD, Guttmacher AE, McKinnon W, et al. Autosomal dominant postaxial polydactyly, nail dystrophy and dental abnormalities map to chromosome 4p16 in the region containing the Ellis–van Creveld syndrome locus. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:1405–1412. doi: 10.1086/301643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Itin PH, Eich G, Fistarol SK. Missing creases of distal finger joints as a diagnostic clue of nail–patella syndrome. Dermatology. 2006;213:153–155. doi: 10.1159/000093857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Judge DP, Dietz HC. Marfan’s syndrome. Lancet. 2005;366:2965–1976. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67789-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaplan FS. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: a historical perspective. Clin Re Bone Miner Metab. 2005;3:178–181. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaplan FS, Tabas JA, Gannon FH, et al. The histopathology of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: an endochondral process. J Bone Jt Surg. 1993;75A:220–230. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199302000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kitoh H, Kitakoji T, Kurita K, et al. Deformities of the elbow in achondroplasia. J Bone Jt Surgery. 2002;84B:680–683. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B5.13107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kopits S. Orthopedic complications of dwarfism. Clin Orthop. 1976;114:153–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuijpers TW, Ridanpää M, Peters M, et al. Short-limbed dwarfism with bowing, combined immune deficiency and late onset aplastic anaemia caused by novel mutations in the RMPR gene. J Med Genet. 2003;40:761–766. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.10.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kunzler A, Farmand M. Typical changes in the viscerocranium in acromegaly. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1991;19:332–340. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lachman RS, Rimoin DL, Hollster DW, et al. The Kniest syndrome. AJR. 1975;123:805–814. doi: 10.2214/ajr.123.4.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leighton SE, Papsin B, Vellodi A, et al. Disordered breathing during sleep in patients with mucopolysaccharidoses. Int J Pediatr Otrorhinolaryngol. 2001;58:127138. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(01)00417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levine MA. Parathyroid hormone resistance syndromes. In: Favus MJ, editor. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. 4. Philadelphia: William and Wilkins; 1999. pp. 230–253. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lieberman SA, Bjorkengren AG, Hoffman AR. Rheumatologic and skeletal changes in acromegaly. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1992;21:615–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lucky AW, Tsang R. Clinical vignette: pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism presenting with osteoma cutis. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:995. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.6.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mäkitie O, Kaitila I. Cartilage–hair hypoplasia—clinical manifestations in 108 Finnish patients. Eur J Pediatr. 1993;152:211–217. doi: 10.1007/BF01956147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mäkitie O, Marttinen E, Kaitila I. Skeletal growth in cartilage–hair hypoplasia: a radiological study of 82 patients. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:434–439. doi: 10.1007/BF02013505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maldjian C, Chew FS, Klein R, et al. Kniest dysplasia: new radiographic features in the skeleton. Radiology Case Reports. 2007;2:72–77. doi: 10.2484/rcr.v2i2.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maroteaux P, Lamy M. Hurler’s disease. Morquio’s disease and related mucopolysaccharidoses. J Pediat. 1965;67:312–323. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(65)80256-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Maumenee IH. The eye in the Marfan syndrome. Trans Am Opthalmol Soc. 1981;79:684–733. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mavrodontidis AN, Zalavras CG, Papadonikolakis A, Soucacos NN. Bilateral absence of the patella in nail–patella syndrome: delayed presentation with anterior knee instability. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:e89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McIntosh I, Clough MV, Schaffer AA, et al. Fine mapping of the nail–patella syndrome locus at 9q34. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:133–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McKusick VA. Ellis–van Creveld syndrome and the Amish. Nature Genet. 2000;24:203–204. doi: 10.1038/73389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mostafa MI, Temtamy SA, el-Gaammal MA, Mazen IM. Unusual pattern of inheritance and orodental changes in the Ellis–van Creveld syndrome. Genet Couns. 2005;16:75–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Muenzer J. The mucopolysaccharidoses: a heterogeneous group of disorders with variable pediatric presentations. J Pediatr. 2004;144:S27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Neufeld EF, Muenzer J. The mucopolysaccharidoses. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, editors. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. 8. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc; 2001. pp. 3421–3452. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ponseti IV. Skeletal growth in achondroplasia. J Bone Jt Surg. 1970;52A:701–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ridanpää M, Sistonen P, Rockas S, et al. Worldwide mutation spectrum in cartilage–hair hypoplasia: ancient founder origin of the major 70A–>G mutation of the untranslated RMRP. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10:439–447. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rimoin DL, Lachman RS. Genetic disorders of the osseous skeleton. In: Beighton P, editor. McKusick’s heritable disorders of connective tissue. 5. St Louis: Mosby; 1993. pp. 557–689. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rimoin DL, Lachman RS. Genetic disorders of the osseous skeleton: Kniest-Stickler dysplasia group. In: Beighton P, editor. McKusick’s heritable disorders of connective tissue. 5. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993. pp. 601–605. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rousseau F, Bonaventure J, Legeai-Mallet L, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 in achondroplasia. Nature. 1994;371:252–254. doi: 10.1038/371252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sartoris DJ, Reznick D. The horn: a pathognomonic feature of paediatric bone dysplasias. Aus Paediatr J. 1987;23:347–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1987.tb00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sato U, Kitanaka S, Sekine T, et al. Functional characterization of LMX1B mutations associated with nail–patella syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:783–788. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000157674.63621.2C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schroeder HW, Zasloff M. The hand and foot malformations in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Johns Hopkins Medical J. 1980;147:73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Seitz CS, Hamm H. Congenital brachydactyly and nail hypoplasia: clue to bone-dependent nail formation. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1339–1342. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sergi C, Voightlander T, Zoubaa S, et al. Ellis–van Creveld syndrome: a generalized dysplasia of enchondral ossification. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:289–293. doi: 10.1007/s002470000421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shih SL, Lee YJ, Lin SP, et al. Airway changes in children with mucopolysaccharidoses. Acta Radiol. 2002;43:40–43. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0455.2002.430108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shore EM, Feldman GJ, Xu M, Kaplan FS. The genetics of fibrodysplasia ossificans progessiva. Clin Rev Bone Mineral Metab. 2005;3:201–204. doi: 10.1385/BMM:3:3-4:201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sulisalo T, Sistonen P, Hästbacka J, et al. Cartilage–hair hypoplasia gene assigned to chromosome 9 by linkage analysis. Nat Gent. 1993;3:338–341. doi: 10.1038/ng0493-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Velde S, Fillman R, Yandow S. Protrusio acetabuli in Marfan syndrome: history, diagnosis and treatment. J Bone Jt Surg. 2006;88A:639–646. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Whitely CB. Mucopolysaccharidosis Type VI. In: Beighton P, editor. McKusick’s heritable disorders of connective tissue. 5. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993. pp. 442–450. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Whitely CB. Mucopolysaccharidosis Type IV. In: Beighton P, editor. McKusick’s heritable disorders of connective tissue. 5. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993. pp. 431–441. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Whitley CB. The mucopolysaccharidoses. In: Beighton P, editor. McKusick’s heritable disorders of connective tissue. 5. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993. pp. 367–499. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wilson WG, Aylsworth AS, Folds JD, Whisnant JK. Cartilage–hair hypoplasia (metaphyseal chondrodysplasia, type McKusick) with combined immune deficiency: variable expression and development of immunologic functions in sibs. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1978;XIV(6A):117–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Woo CC. Radiological features and diagnosis of acromegaly. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1988;11:2306–2213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wraith JE, Alani SM. Carpal tunnel syndrome in the mucopolysaccharidoses and relted disorders. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:962–963. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.9.962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]