Abstract

The Gorham–Stout syndrome is a rare condition in which spontaneous, progressive resorption of bone occurs. The aetiology is poorly understood. We report a patient with osteolysis of the metacarpal bones in both hands due to an increased number of stimulated osteoclasts. This suggests that early potent antiresorptive therapy with bisphosphonates may prevent local progressive osteolysis.

Keywords: Gorham–Stout syndrome, Osteolysis, Biphosphonates

Introduction

Idiopathic osteolysis was first described in 1838 and again in 1872 by Jackson [23, 24], who reported a case of a ‘boneless arm’. The humerus of an 18-year-old man disappeared completely in the course of 11 years, during which he twice sustained a spontaneous fracture of the bone. In spite of the disease, he was able to do manual labour until his death at the age of 70 years. In 1955, Gorham and Stout defined a specific disease entity [11] and reviewed 24 cases from the literature.

A patient with osteolysis of the both hands treated by anti-osteoclastic medication (alendronate) is reported.

In the past 50 years, numerous papers have been published to make the medical community aware of this rare entity, and to discuss the etiopathology, clinical presentation, radiographic findings, and treatment options for patients with Gorham’s disease.

Case Report

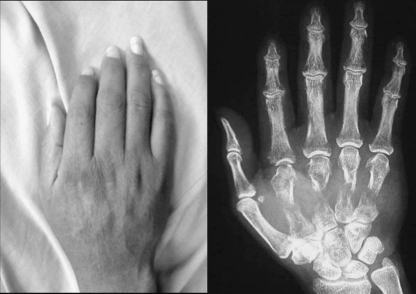

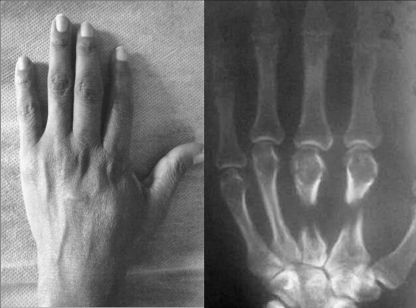

A 42-year-old woman was referred to us for pain, deformity and limited motion of both hands. Radiographs showed a massive osteolysis of second to fifth right metacarpal bones (Fig. 1) and second to third left metacarpal bones (Fig. 2). Her history was significant for a pathological fracture of the left hip and sixth thoracic vertebra, which happened 2 years earlier). The fracture of the hip was treated with an intramedullary nail and no bone biopsy was done (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Radiographs showing a massive osteolysis of second to fifth right metacarpal bones

Fig. 2.

Radiographs showing a massive osteolysis of second and third left metacarpal bones

Fig. 3.

Fracture of the left hip was treated with an intramedullary nail and no bone biopsy was done

Her general condition was good and laboratory investigations were normal apart from a slight elevation of the alkaline. Serum protein electrophoresis verified a monoclonal band of IgG. All microbiological tests proved negative.

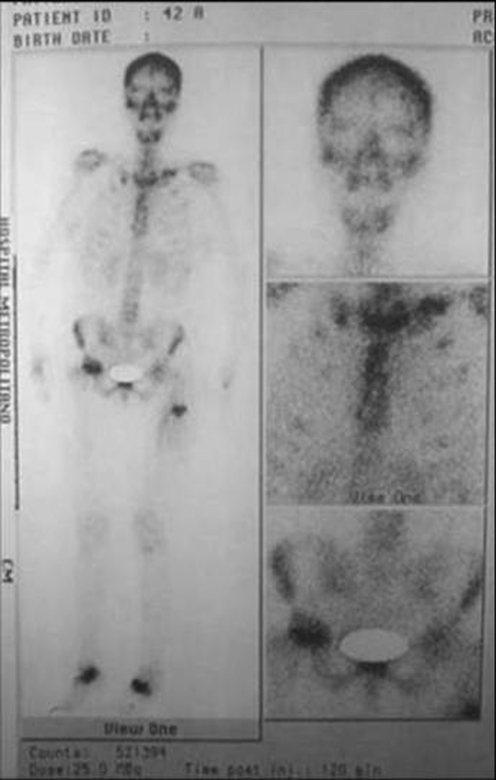

A Tc-99m MDP whole-body scan revealed increased bone activity in left clavicle, right femoral head, upper third of left femur and tarsal bones (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

A Tc-99m MDP whole-body scan revealed increased bone activity in left clavicle, right femoral head, upper third of left femur and tarsal bones

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) of the spine, and total body revealed osteopenia.

The lytic area of the second right metacarpal bone was curetted. The histology showed considerable vascular fibrous tissue with destruction of the spongiosa, fragments of which were surrounded by active osteoclasts. There was no evidence of malignancy. Based on all of these findings, a diagnosis of Gorham’s disease was given.

The patient was treated by anti-osteoclastic medication (alendronate). She was reviewed 6 months later with no clinical or radiological signs of progression or recurrence of the disease.

Discussion

Vanishing bone disease is a rare idiopathic disease leading to extensive loss of bony matrix, which is replaced by proliferating thin-walled vascular channels and fibrous tissue [36]. Although the disease can be monostotic or polyostotic, multicentric involvement is unusual [35].

The patients whom we present had monocentric osteolytic changes as adults; there was no family history of bone disease or of renal involvement. According to the classification proposed by Hardegger et al. [18], they belong to the group defined as the Gorham–Stout syndrome.

The exact pathogenetic mechanism of Gorham–Stout syndrome is still unknown. There is controversy even over the presence or absence of osteoclasts in the condition. Several authors believe that angiomatosis is responsible [9, 11, 26].

Incidence of the disease may be linked to a history of minor trauma, although as many as half of the patients have no history of trauma.

Most cases occur in children or in adults <40 years. The bones of the upper extremity and the maxillofacial region are the predominant osseous locations of the disease.

Leriche’s hypothesis that post-traumatic arterial hyperemia was responsible for bone resorption was rejected first by Mouchet, and later by Gorham et al. [12]. The same authors postulated that an angioma might act as a shunt, increasing local oxygen tension [12].

In most cases, trauma was relatively trivial, and in some cases, trauma did not occur. As with many other diseases, the role of trauma in vanishing bone disease may be to signal the presence of a preexisting abnormality.

The process may affect the appendicular or the axial skeleton. The shoulder and the pelvis are the most common sites of involvement; however, various locations such as the humerus, scapula, clavicle, ribs, sternum, pelvis and femur can be affected by Gorham’s disease. The disorder is also known to occur at other sites such as the skull, mandible, maxillofacial skeleton, spine, hand and foot.

Our search in English and international literature revealed only five cases with hand and wrist involvement by Gorham’s disease [2, 3, 6, 27, 34]. In all the described cases, the disease was unifocal and the phalanges were minimally affected. Tunon and Gonzalez [34] presented a 24-year-old man with angiomatosis of the right hand and complete destruction of the second, third and fourth metacarpals. Carneiro and Steglich [2] treated a 13-year-old girl with extensive metacarpal bone osteolysis of the right hand. Chalidis and Dimitriou [3] reported a case with phalangeal osteolysis treated by intercalary bone grafting (Table 1).

Table 1.

Previous cases reported in the international literature with hand and wrist involvement by Gorham’s disease

| Author | Description | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Tunon and Gonzalez [34] | 24-year-old man with angiomatosis of the right hand and complete destruction of the second, third, and fourth metacarpals | The affected metacarpals with the distal row of the carpus were extirpated, and the remaining defect was filled with a bone graft taken from the iliac crest |

| Carneiro and Steglich [2] | 13-year-old girl with extensive metacarpal bone osteolysis of the right hand | Corticocancellous bone grafting (failed) radiation therapy |

| Dickson et al. [6] | 13-year-old girl with extensive metacarpal bone osteolysis of the right hand | Corticocancellous bone grafting (failed) radiation therapy |

| Lehnhardt et al. [27] | 30-year-old woman with osteolysis of the right hand | Radiotherapy and repeated bone grafting of the third, fourth, and fifth metacarpals |

| Chalidis and Dimitriou [3] | 31-year-old, left-handed woman | 10 mg alendronate sodium |

| Multicentric and massive bilateral hand osteolysis. | Staged intercalary iliac bone grafting of the phalanges of the dominant thumb and index finger |

The diagnosis of vanishing bone disease is based on clinical examination, radiologic imaging studies and histopathologic examination of the affected area. Vanishing bone disease is not accompanied by general symptoms. Dull aching, weakness in the affected extremity, swelling and skeletal deformities are prominent symptoms [31].

Laboratory findings are not specific and of no value in the diagnostic procedure, as occurred in our cases. An elevated alkaline phosphatase level has been reported in a patient with an associated fracture [25]. Devlin et al. [5] also suggested that increased levels of interleukin-6 might act as a potential mediator of increased osteoclast activity in patients with vanishing bone disease.

Radiographs are the best tools for detecting vanishing bone disease [32]. The radiographic appearance becomes diagnostic of vanishing bone disease when unilateral partial or total disappearance of contiguous bones, tapering of bony remnants, and absence of a sclerosing or osteoblastic reaction are present. Pertinent negative radiographic findings are absence of phleboliths, vascular or soft-tissue calcification, coarse trabeculation and any related bony abnormality with the exception of demineralisation resulting from disuse. In our case, the bilateral partial disappearance of the metacarpal bones was evident radiographically (Fig. 1).

Histologically, the appearance depends on the phase in which the disease is diagnosed. In 1983, Heffez et al. [19] described two phases. The first phase represents increased vascular concentration in the bone-displacing fibrous tissue part; in the second phase, only fibrous tissue is found. The presence and number of osteoclasts vary significantly in vanishing bone disease. In most cases, osteoclastic activity is minimal or nonexistent, whereas in other cases, osteoclasts are easily identifiable [7]. If present, osteoclastic activity is concentrated in the interface between the vascular channels and the cortex [22].

The differential diagnosis should exclude other causes of osteolysis such as skeletal angiomas, essential osteolysis, hereditary osteolysis, infection, trauma (Sudeck atrophy), endocrine disease, rheumatoid arthritis, various nervous system diseases and tumors [21].

Gorham disease is a combined clinical, radiographic and histologic entity. It is characterized by a nonfamilial, histologically benign vascular proliferation originating in bone and producing complete lysis of all or a portion of the bone [4].

Usually, the prognosis depends on complications, such as neurological deficits or pleural effusion. It has been reported that >15% of patients die as a result of their disease. Life expectancy is not affected if the extremities are involved.

The treatment of vanishing bone disease is controversial. A review of the literature led to the conclusion that there is no consensus about the most efficacious treatment.

Apart from standard orthopaedic treatment for fractures, non-unions and deformities, the medical treatment for Gorham’s Disease falls into three groups:

Anti-osteoclastic medication (biphosphonates) and interferon. Synergistic action of zoledronic acid and Interferon is a powerful antiangiogenic therapy, which is currently giving the best results [14, 15, 29].

Radiotherapy. Radiotherapy acts by accelerating sclerosis of the proliferating blood vessels and prevents regrowth of these vessels. Although the use of total doses from 30 Gy to 45 Gy has been reported to be effective, some authors reported excellent results while using a total dose of 15 Gy in a case that involved the upper extremity [8, 16, 17, 28].

Surgical intervention has been suggested as the method of choice when feasible and involves local resection of the affected bone, with or without replacement prostheses or bone grafts [13, 33].

The usefulness of all these treatments is also shaped by the severity of the disease and the urgency of the patient’s condition.

The prognosis varies from slight disability to death by involvement of vital skeletal structures. It has been reported that >15% of patients die as a result of their disease. Severe disability results from involvement of the pelvis, thorax and cervical spine. Neurological complications increase the mortality to 33.3% [20]. However, the disease usually remains localized within a skeletal region and undergoes eventual spontaneous arrest [1, 10, 20, 30].

Vanishing bone disease is a rare disease of unknown aetiology. It is characterized by spontaneous and progressive destruction and disappearance of the bone, and is associated with a vascular abnormality, angiomatosis or hemangiomatosis.

The Gorham–Stout syndrome may be essentially a monocentric bone disease with a focally increased bone resorption due to an increased number of paracrine- or autocrine-stimulated hyperactive osteoclasts. The resorbed bone is replaced by a markedly vascularised fibrous tissue.

The apparent contradiction concerning the presence or absence or the number of osteoclasts, may be explained by the different phases of the syndrome.

Our histopathological study provides good evidence of hyperactive osteoclastic bone resorption causing osteolytic changes. It seems reasonable to suggest that antiresorptive therapy, for example with bisphosphonates or calcitonin, started in an early phase of the disease, could lead to a dramatic improvement in the treatment of progressive osteolytic changes.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest The author declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bode-Lesniewska B, Hochstetter A, Exner GU, Hodler J. Gorham–Stout disease of the shoulder girdle and cervico-thoracic spine: fatal course in a 65-year-old woman. Skeletal Radiol. 2002;31:724–729. doi: 10.1007/s00256-002-0568-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carneiro RS, Steglich V. “Disappearing bone disease” in the hand. J Hand Surg. 1987;12A:629–634. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(87)80225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalidis BE, Dimitriou CG. Intercalary bone grafting for the reconstruction of phalangeal osteolysis in disappearing bone disease: case report. J Hand Surg. 2008;33A:1873–1877. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choma ND, Biscotti CV, Bauer TW, Mehta AC, Licata AA. Gorham’s syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Med. 1987;83(6):1151–1156. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90959-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devlin RD, Bone HG, Roodman GD. Interleukin-6: a potential mediator of the massive osteolysis in patient with Gorham–Stout disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(5):1893–1897. doi: 10.1210/jc.81.5.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickson GR, Hamilton A, Hayes D, Carr KE, Davis R, Mollan RA. An investigation of vanishing bone disease. Bone. 1990;11:205–210. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(90)90215-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickson GR, Mollan RAB, Carr KE. Cytochemical localization of alkaline and acid phosphatase in human vanishing bone disease. Histochemistry. 1987;87(6):569–572. doi: 10.1007/BF00492472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fontanesi J. Radiation therapy in the treatment of Gorham disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:816–817. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200310000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fretz CJ, Jungi WF, Neuweiler J, Haertel M. The malignant degeneration of Gorham Stout disease? Rofo-Fortschr Geb Rontgenstr Neuen Bildgeb Verfahr. 1991;155:579–581. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1033321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujio K, Kanno R, Suzuki H, Nakamura N, Gotoh M. Chylothorax associated with massive osteolysis (Gorham’s syndrome) Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1956–1957. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)03413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorham LW, Stout AP. Massive osteolysis (acute spontaneous absorption of bone, phantom bone, disappearing bone): its relation to hemangiomatosis. J Bone Jt Surg [Am.] 1955;37A:985–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorham LW, Wright AW, Schultz HH, Maxon FC. Disappearing bones: a rare form of massive osteolysis: report of 2 cases, 1 with autopsy findings. Am J Med. 1954;17(5):674–682. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(54)90027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gratz KW, Prein J, Remagen W. A reconstruction attempt in progressive osteolysis (Gorham disease) of the mandible: a case report [in German] Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. 1987;97(8):980–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagberg H, Lamberg K, Astrom G. Alpha-2b interferon and oral clodronate for Gorham’s disease. Lancet. 1997;350(9094):1822–1823. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63639-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammer F, Kenn W, Wesselmann U, Hofbauer LC, Delling G, Allolio B, et al. Gorham–Stout disease—stabilization during bisphosphonate treatment. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:350–353. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunbar SF, Rosenberg, Mankin H, Rosenthal D, Suit HD. Gorham’s massive osteolysis: the role of radiation therapy and a review of the literature. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;26(3):491–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Hanly JG, Walsh NM, Bresnihan B. Massive osteolysis in the hand and response to radiotherapy. J Rheumatol. 1985;12(3):580–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardegger F, Simpson LA, Segmueller G. The syndrome of idiopathic osteolysis: classification, review and case report. J Bone Jt Surg [Br.] 1985;67-B:89–93. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.67B1.3968152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heffez L, Doku HC, Carter BL, Feeney JE. Perspectives of massive osteolysis: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;55(4):331–343. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(83)90185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hejgaard N, Olsen PR. Massive Gorham osteolysis of the right hemipelvis complicated by chylothorax: report of a case in a 9-year-old boy successfully treated by pleurodesis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1987;7(1):96–99. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198701000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holroyd I, Dillon M, Roberts GJ. Gorham’s disease: a case (including dental presentation) of vanishing bone disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89(1):125–129. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(00)80027-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hvos AG. Bone tumors, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson JBS. A boneless arm. Boston Med Surg J. 1838;18:368–369. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson JBS. Absorption of the humerus after fracture. Boston Med Surg J. 1872;10:245–247. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson PM, McClure JG. Observations on massive osteolysis: a review of the literature and report of a case. Radiology. 1958;71(1):28–42. doi: 10.1148/71.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulenkampff HA, Richter GM, Hasse WE, Adler CP. Massive osteolysis in the Gorham–Stout syndrome. Int Orthop. 1990;14:361–366. doi: 10.1007/BF00182645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lehnhardt M, Steinau HU, Homann HH, Steinstraesser L, Druecke D. Gorham–Stout disease: report of a case affecting the right hand with a follow-up of 24 years. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2004;36:249–254. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-821048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Listewnik MJ, Marzecki Z, Kordowski J. Disappearing bone disease: massive osteolysis of the ribs treated with radiotherapy: report of a case. Strahlenther Onkol. 1986;162(5):338–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mawk JR, Obukhov SK, Nichols WD, Wynne TD, Odell JM, Urman SM. Successful conservative management of Gorham disease of the skull base and cervical spine. Childs Nerv Syst. 1997;13:622–625. doi: 10.1007/s003810050155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNeil KD, Fong KM, Walker QJ, Jessup P, Zimmerman PV. Gorham’s syndrome: a usually fatal cause of pleural effusion treated successfully with radiotherapy. Thorax. 1996;51:1275–1276. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.12.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moller G, Priemel M, Amling M, Werner M, Kuhlmey AS, Delling G. The Gorham–Stout syndrome (Gorham’s massive osteolysis): a report of six cases with histopathological findings. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1999;81(3):501–506. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B3.9468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naden BA. When bone disappears. RN. 1995;58(10):26–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Picault C, Comtet JJ, Imbert JC, Boyer JM. Surgical repair of extensive idiopathic osteolysis of the pelvic girdle (Jackson–Gorham disease) J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1984;66:148–149. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tunon JB, Gonzalez FP. Angiomatosis of the metacarpal skeleton. Hand. 1977;9:88–91. doi: 10.1016/S0072-968X(77)80042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Velez A, Herrera M, Rio E, Ruiz-Maldonado R. Gorham’s syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32(12):884–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vinee P, Tanyu MO, Hauenstein KH, Sigmund G, Stover B, Adler CP. CT and MRI of Gorham syndrome. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1994;18(6):985–989. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199411000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]