Abstract

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare cutaneous neuroendocrine neoplasm of possible viral origin and is known for its aggressive behavior. The incidence of MCC has increased in the last 15 years. Merkel cell carcinoma has the potential to metastasize, but rarely involves the central nervous system. Herein, we report three consecutive surgical cases of MCC presenting at a single institution within 1 year. We used intracavitary BCNU wafers (Gliadel®) in two cases. Pathological features, including CK20 positivity, consistent with MCC, were present in all cases. We found 33 published cases of MCC with CNS involvement. We suggest that the incidence of neurometastatic MCC may be increasing, parallel to the increasing incidence of primary MCC. We propose a role for intracavitary BCNU wafers in the treatment of intra-axial neurometastatic MCC.

Keywords: Merkel cell carcinoma, Gliadel, BCNU, Metastasis, Brain

Introduction

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare cutaneous neuroendocrine neoplasm. The prognosis for MCC is poor and the 5-year disease-specific survival is 64% [1]. Patients present with painless erythematous to violaceous nodules on sun exposed regions of the skin. The tumors may ulcerate and grow rapidly within the first few months. Heath et al. highlighted the typical clinical features of this rare form of skin cancer with the acronym “AEIOU” (Asymptomatic, Enlarging rapidly, Immunosuppression, Older age >50, UV exposed site) [2]. Merkel cell carcinoma is locally aggressive with a high rate of local recurrence, regional lymph node involvement, and metastasis. Up to 21% of cases develop distant metastatic disease [1]. Common sites of distant metastatic involvement are the skin, lymph nodes, mediastinum, liver, lung, and bone [3, 4]. Feng et al. [3] reported in 2008 the discovery of a novel polyomavirus—designated Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV)—which was integrated into the genome of 8 out of 10 MCC tumor specimens. Sihto et al. [4] mirrored this finding in a Finnish population-based pathologic analysis, detecting MCPyV DNA in 79.8% of 144 formalin-fixed paraffin embedded MCC specimens that were available for analysis by polymerase chain reaction.

Central nervous system involvement is rare but can occur through hematogenous, lymphatic, or direct extension pathways, and can also undergo dissemination through the cerebrospinal fluid. We identified thirty-three prior cases of neurometastatic MCC in the literature, including both intra-axial and extra-axial transcalvarial disease [3, 5–35]. We herein describe three additional surgical cases of neurometastatic MCC that presented within 1 year at a single institution. We employed the novel treatment strategy of implanting intracavitary BCNU wafers (Gliadel®) in two of the intra-axial cases at the time of resection. Neurometastatic MCC may be emerging as a more common entity than previously thought. The succession of cases we encountered in a short time may suggest an increasing need to address neurometastatic MCC in light of the increased overall incidence of MCC.

Methods

The senior author treated three surgical cases of MCC within 1 year. The medical records were reviewed. Case reports, case series, and literature reviews were identified with a PubMed search using the keywords “MCC” and “brain” without any search limitations. From the references in articles identified through PubMed and found to be relevant, a search was performed using the Web of Science to locate additional case reports, case series or literature reviews cited by the original group of reports derived from PubMed.

Cases

Case 1

A 75-year-old female presented in December 2008 with 3 weeks of acute onset confusion, ataxia, and left sided weakness. She had a series of falling episodes 3 weeks prior to presentation. Computed tomography showed a 2.5 cm hyperdense right parietal mass associated with edema. Her past medical history was significant for a 20 pound weight loss over the past year, chronic urinary tract infections, recurrent basal cell carcinoma, and MCC of the left nasal ala which had been removed 1 year earlier using Mohs micrographic resection followed by adjuvant radiation. Imaging showed a 4 cm cystic-solid intra-axial mass in the right parietal region (Fig. 1a, b). She underwent right parietal craniotomy and gross total resection with implantation of intracavitary BCNU wafers (Gliadel®) followed by adjuvant radiotherapy. She died of systemic complications 7 months after being diagnosed with neurometastatic MCC, and 2 years after her initial diagnosis of cutaneous MCC.

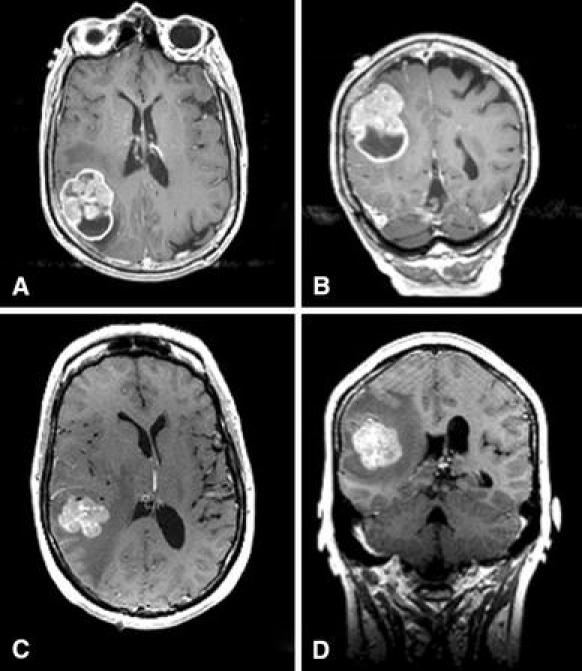

Fig. 1.

T1-weighted gadolinium-enhanced pre-operative MRI of the brain from Case 1 in axial a and coronal b sections demonstrating an irregularly enhancing and partially cystic lesion in the right parietal lobe, with minimal surrounding edema. T1-weighted gadolinium-enhanced pre-operative MRI of the brain from Case 2 in axial c and coronal d sections demonstrating an irregularly enhancing lesion in the right posterior temporal lobe, with minimal surrounding edema and shift of the midline structures to the left

Case 2

A 51-year-old female presented in January 2008 with intermittent headaches and nausea for 2 months. She had a Mohs procedure for MCC of the right calf 4 years earlier. Metastatic progression was treated with resection of right inguinal lymph nodes in 2004, and splenectomy and right salpingo-oophorectomy in 2006. The MRI demonstrated a 3.2 × 3.2 × 2.6 cm right posterior temporal lobe enhancing mass with considerable surrounding edema, mass effect, and right-to-left midline shift (Fig. 1c, d). She underwent craniotomy and gross total resection with implantation of BCNU (Gliadel®) intracavitary wafers, as well as adjuvant whole brain radiation. In August of 2008, a radical left neck dissection was undertaken for MCC involvement of the left trapezius muscle and cervical, supraclavicular, and sub trapezius lymph nodes. At 21 months after craniotomy, the patient had occasional memory and balance trouble but was working full time. She had no evidence of radiographic recurrence on follow-up MRI.

Case 3

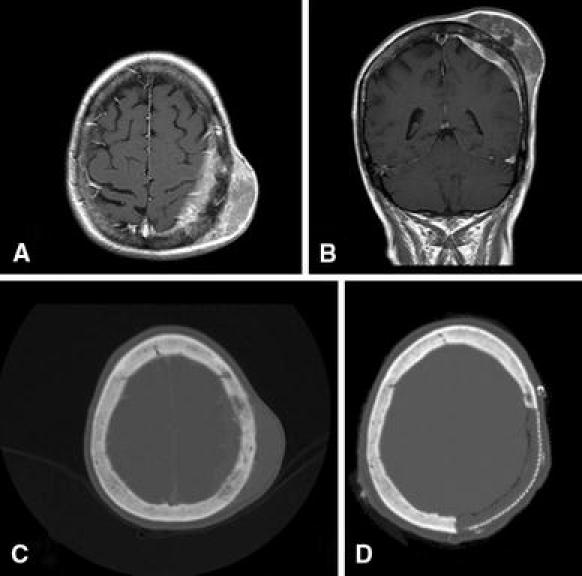

A 77-year-old female presented with headaches and swelling and tenderness of the left frontoparietal scalp in July of 2008. Seven months prior to presentation, she noticed a slight bump on her head that gradually enlarged and became painful. The past medical history was significant only for cataracts and left retinal detachment. The review of systems was positive for a 10 pound weight loss and easy bruising. On physical exam, a 6.0 × 7.0 cm mass over the left anterior parietal area was noted. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a heterogeneously enhancing necrotic left parietal scalp mass extending into the subgaleal and epidural spaces and infiltrating the bone (Fig. 2a, b). A CT scan of the head similarly showed extensive subgaleal tumor subtended by epidural tumor (Fig. 2c). There was some subtle calvarial change with remodeling, but no evidence of gross osteolysis. A transcutaneous biopsy in the clinic revealed a poorly differentiated carcinoma but prolonged formalin fixation precluded further diagnosis. She underwent a left parietal craniectomy and resection of the lesion. Intraoperatively, the tumor was entirely subgaleal, with involvement of the periosteum. No dermal involvement was noted. The bone was mottled with some evidence of remodeling. The mass was peeled off the dura. The resected calvarium was elevated as a free flap and was structurally intact. We were therefore able to utilize the resected bone as a template to fashion an anatomically precise titanium mesh and methylmethacrylate cranioplasty before sending the specimen to pathology (Fig. 2d). Pathologic analysis revealed MCC. The patient refused adjuvant radiation or chemotherapy. She was without apparent recurrence until 16 months after surgery, at which time local and contralateral CNS recurrence of the tumor involving scalp, skull, and dura occurred, both ipsilaterally at the margin of the prior resection, and contralaterally in a non-contiguous location involving again the calvaria, dura, and subgaleal space. The patient declined any further therapy.

Fig. 2.

T1-weighted gadolinium-enhanced pre-operative MRI of the brain from Case 3 in axial a and coronal b sections demonstrating a subgaleal mass with involvement of the underlying bone and dura. Pre-operative axial head CT with bone windows c scan demonstrates subtle bony change with slightly irregular hyperostotic calvarium, but no gross osteolysis. Postoperative axial head CT shows the region of calvarial reconstruction with titanium mesh and methylmethacrylate d

Pathology

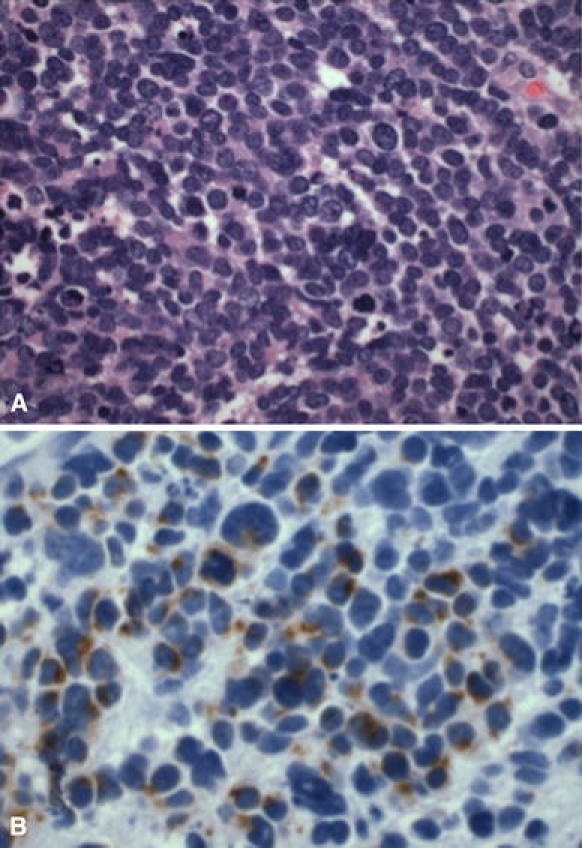

All three CNS specimens had similar gross and microscopic features. The gross specimens were pink-tan. Foci of necrosis were noted in Case 1 and 2 and abundant areas of both hemorrhage and necrosis were noted in case 2. Histological study revealed dyshesive cells arranged in an ill-defined nodular and focally trabecular pattern (Fig. 3a). This highly cellular uniform population of small round cells had scant eosinophilic rims of cytoplasm and round vesicular nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli. There were numerous mitotic figures. Immunohistochemistry with cytokeratin 20 (CK20) displayed paranuclear staining pattern in all three cases (Fig. 3b). Electron microscopy was performed on Case 2 and demonstrated a neoplasm with clumped nuclear chromatin and scant cytoplasm filled with dispersed ribosomes and mitochondria. Higher magnification showed scattered nuclei with dense granular nuclear inclusions. In Case 2, cytogenetics was done and yielded a translocation, t (7; 11). Pathologic samples were analyzed for the presence of polyomavirus. On agarose gel electrophoresis, bands were identified that were consistent with expected size of polyomavirus PCR product from all samples, but after the sequencing and analysis using the Genbank database, the sequences did not match polyomavirus. Based on these findings, polyomavirus in these samples could not be detected.

Fig. 3.

Case 2 a Light micrograph of the metastatic MCC specimen stained with hematoxylin and eosin at ×60 magnification shows a highly cellular specimen comprised of small to medium sized round cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. The oval nuclei have a fine granular chromatin pattern. Mitotic figures were evident. b Light micrograph of the metastatic MCC specimen stained with CK-20 at ×60 magnification displays the paranuclear dot staining pattern typical of MCC

Literature review

We identified 33 cases of neurometastatic MCC from a review of the literature (Table 1) [5–20, 29, 30]. Five of these cases were reported in the context of case series for which individual patient data was not available [18, 21, 29]. Several duplicate cases were identified which had been previously published [22, 23]. The mean age of patients was 63 ± 11 years. Neurometastatic disease in MCC appeared at the time of initial diagnosis in eight cases, typically in association with disease associated with a scalp or head and neck lesion extending directly through the calvaria or skull base into the intracranial space. Alternatively, neurometastatic disease was delayed over 3 years from the time of initial MCC diagnosis in 18% of cases for which data was available. For those patients who presented with intraparenchymal brain lesions without transcalvarial involvement, the median time delay after the diagnosis of the primary cutaneous lesion was 16 months. The mean survival time after a diagnosis of CNS metastasis including transcalvarial metastasis was estimated as greater than or equal to 10 months and the median survival time was greater than or equal to 8.5 months.

Table 1.

Results of literature review

| Publication | Age/sex | Location of metastasis | Treatment prior to CNS disease | Treatment for CNS metastasis | Time to CNS disease after Primary Dx | Survival after CNS metastasis | Overall survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kroll et al. [13]a | 48 M | Brain | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Kroll et al. [13]a | 70 M | Brain | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Kroll et al. [13]a | 72 F | Meninges | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Wick et al. [5]a | 62 M | Brain | SR, RT, chemo | No treatment | 12 M | 1 M | 13 M |

| Wick et al. [5]a | 76 M | Brain | SR | No treatment | 3 Y | 0 M | 36 M |

| Goepfert et al. [18]b | ? | Brain | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Grosh et al. [17]a | 57 F | Brain | SR | WBRT, chemo | 2 M | 12 M | 14 M |

| Grosh et al. [17]a | 56 M | Brain | SR | WBRT, chemo | ≥21 M | ? | ? |

| Hitchcock et al. [16]a | 52 M | Brain | SR | WBRT, chemo | 3 M | 9 M | 12 M |

| Knox et al. [14]a | 75 F | Brain | SR, RT, HT | WBRT | 4 Y | ? | ? |

| Knox et al. [14] | 60 M | Leptomeninges | SR, RT, chemo | WBRT, IT chemo | 10 M | 14 M | 24 M |

| Dudley et al. [36] | 64 M | Leptomeninges | SR, RT, chemo | No treatment | 17 M | 6 days | 17 M |

| Alexander et al. [35] | 56 M | Brain | – | Biopsy, Wbrt, chemo | Present at dx | 3 Y | 36 Y |

| Wojak and Murali [30] | 78 F | Calvaria, Dura | – | SR, LRT | Present at dx | ≥1 Y | ≥12 M |

| Manome et al. [11] | 57 F | Skull Base, Brain | – | RA | Present at dx | ? | ? |

| Small et al. [8] | 56 M | Brain | – | Biopsy, WBRT | Present at dx | 22 M | 22 M |

| Yiengpruksawan et al. [29]a,b | ? | Brain | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Sharma et al. [9]a | 57 M | Brain | – | WBRT, Chemo | Present at dx | 13 M | 13 M |

| Snodgrass et al. [7]a,c | 61 M | Brain, Leptomeninges | SR, chemo | WBRT, IT Chemo | 1 Y | 6 M | 18 M |

| Eftekhari et al. [21]a,b | ? | Brain | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Eftekhari et al. [21]a,b | ? | Brain | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Eftekhari et al. [21]a,b | ? | Brain | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Matula et al. [10] | 47 M | Skull Base, Dura, Brain | – | SR, RT, Chemo | Present at dx | 12 M | 12 M |

| Straka et al. [6]a | 71 F | Brain | SR, RT | Chemo | 10 M | 2 M | 12 M |

| Litofsky et al. [12] | 86 F | Brain | SR | SR, RT | 16 M | ≥8 M | 24 M |

| Ikawa et al. [15] | 48 F | Brain | SR, RT | SR, WBRT + boost, chemo | 5 Y | 11 M | 71 M |

| Eggers et al. [37] | 69 M | Brain, Leptomeninges | SR, RT, Chemo | WBRT + boost | 17 M | <2 M | 18 M |

| Barkdull et al. [34] | 55 M | Calvaria, Dura | – | SR, LRT, Chemo | Present at dx | 10 M | 10 M |

| Faye et al. [20]a | 85 M | Calviaria, Dura | SR, RT | Chemo | 1 Y | ? | ? |

| Faye et al. [20] | 68 M | Brain, Leptomeninges | SR | SR, RT | 1 Y | 7 M | 19 M |

| Chang et al. [32] | 45 M | Leptomeninges | SR, RT, Chemo | IT Chemo, WBRT | 2 Y | ≥3 M | ≥25 M |

| De Cicco et al. [38]a | 69 M | Brain | SR, Chemo | No treatment | 22 M | 6 M | 28 M |

| Feletti et al. [19] | 65 F | Pituitary | SR | SR, Radiosurgery, Chemo | 3.5 Y | ≥8 M | ≥50 M |

| Present series | 75 F | Brain | SR | SR + ICC, WBRT | 1 Y | 7 M | 19 M |

| Present series | 77 F | Calviaria, Dura | – | SR | Present at dx | ≥16 M | ≥16 M |

| Present series | 51 F | Brain | SR | SR + ICC, WBRT | 4 Y | ≥21 M | ≥69 M |

The Table lists the cases of MCC with metastasis to the CNS or its coverings. SR surgical resection, WBTR whole brain radiotherapy, LRT local radiotherapy, RT radiotherapy NOS, IT intrathecal, ICC intracavitary chemotherapy, RS radiosurgery, HT hyperthermic therapy

aPathology from CNS metastasis not confirmed or of unknown confirmation status

bCase abstracted from large series, individualized data not available

cPatient presented with Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome

We attempted to stratify the cases based on treatment received prior to the development of neurometastatic disease. The data was too limited and varied to draw any meaningful conclusions. Progression and survival times were variously reported in years or months, and often the time had to be inferred. In 8 out of 36 cases, there was insufficient data regarding treatment or follow-up. In eight more cases, the CNS disease was discovered at the time of initial presentation of MCC. All cases with prior disease were treated with surgical resection of the primary lesion, and various combinations of chemotherapy and radiation therapy were applied to a subset of cases (Table 1). There was no difference from the time of initial diagnosis to neurometastatic progression between resection of the primary lesion alone versus various combinations of adjuvant therapy (21 M ± 16 M and 22 M ± 16 M, P = 0.9). When we examined the available data on the overall survival, no difference could be detected between those patients who had resection only and those who had resection with adjuvant therapy prior to neurometastatic progression (21 M ± 18 M and 20 M ± 16 M, P = 0.9).

Discussion

First described in 1972 by Tang and Toker [24] MCC is a rare cutaneous neuroendocrine neoplasm with an aggressive clinical course. The cell of origin is thought to be the Merkel cell, eponymously named by Robert Bonnet for the German anatomist Friedrich Sigmund Merkel [25], who described the cell type in 1875. Merkel cells are primitive neurons derived from the neural crest, which function as mechanoceptors for discriminatory light touch but which also have neuroendocrine function. Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare form of skin cancer and carries a poor prognosis. Merkel cell carcinoma has been synonymously referred to as Merkel cancer, Merkel cell cancer, trabecular carcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin, primary small cell carcinoma of the skin, “murky cell carcinoma” and cutaneous apudoma. The mortality rate of MCC is twice that of melanoma (33 vs. 15%) [26]. Typically, erythematous to violaceous painless nodules appear on sun-exposed regions of the skin. Ulceration may occur and the tumors may grow rapidly within a few months.

The incidence of MCC is rising. Hodgson [27] investigated the incidence trend and found a threefold increase in incidence within a 15-year period. This may be due to an increasingly aged population demographic as well as to more extensive sun exposure. Alternatively, increased awareness of MCC and more accurate diagnosis through the advent of the immunohistochemical marker CK20 may account in part for this increasing trend [2]. This small round cell tumor of the skin should be distinguished from small cell lung carcinoma, malignant lymphoma, metastatic primitive neuroendocrine tumors, and malignant melanoma [28]. These entities can be differentiated using histology and immunohistochemical markers. Small cell lung cancer and non-small cell cancer can be ruled out with TTF-1. HMB45 and MelA are markers for melanoma. CK20 can be used as a marker for MCC. A paranuclear dot staining pattern of low molecular weight cytokeratin 20 (CK20) is a hallmark of MCC (Fig. 3b). Aberrations of chromosome 11 have been seen in MCC [4, 36, 39] and cytogenetic analysis in Case 2 of the present series yielded a translocation at this locus.

Merkel cell carcinoma is locally aggressive by direct tissue extension, spreads to local lymphatic basins, and is characterized by distant hematogenous metastasis. In one large series of 251 patients, twenty-one percent developed distant metastatic disease. The development of distant metastasis was positively correlated with the stage (I–III) on presentation, and adjuvant chemotherapy was not protective against spread [1]. The most common locations for metastasis include the liver, mediastinum, and para-aortic lymph nodes [1]. Voog et al. [31] reviewed 107 cases of MCC complied from the literature, and found the following metastatic sites: skin (33%), lymph nodes (32%), liver (16%), lung (12%), bone (11%), brain (7%), and less than 2% each for bone marrow, pleura, pancreas, testis, small bowel, and stomach.

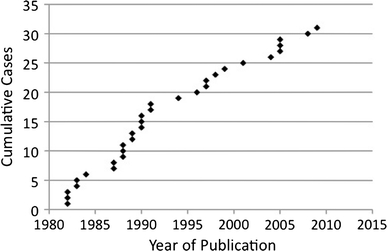

Central nervous system involvement of MCC is thought of as a rare event [7, 19, 32], although an early case series of 30 patients with “trabecular carcinoma” (aka MCC) revealed that 10% had CNS involvement (two cases involving brain and one involving the meninges) [13]. Eftekhari found only three cases of brain involvement among a series of 93 patients with MCC (3%) [21] and Yiengspruksawan [29] mentioned one instance of brain involvement within a series of 70 patients (~1%). Since 1982, a steady trickle of case reports describing neurometastatic MCC have been published (Fig. 4). We note however that it is impossible draw any conclusions about incidence rate from reviewing the publication of case reports. An increased length of survival after diagnosis, made possible through multimodal therapies for primary disease, may lead to an increased incidence of neurometastatic disease. Thirty-three cases have been described in the literature. We describe three additional cases of neurometastatic disease that presented as a cluster within the period of 1 year. It is possible that this pattern occurred simply by chance. Alternatively, these cases may portend a rise in this neurometastatic histology, driven by the increasing incidence trends and prolonged survival exposure of MCC overall.

Fig. 4.

The graph depicts the cumulative number of case reports and case series describing neurometastatic MCC vs. the year of publication

We could not discern any unique demographic or prior treatment characteristics of the patients in our series. All were over 50 and in one patient presented with calvarial and intracranial involvement as a first presentation of disease. The other two patients had previously had aggressive local therapy, including Mohs procedures, but neither had received systemic chemotherapy. We note that all three of the metastatic MCC specimens in our series were negative for polyomavirus. This is consistent with the report by Sihto et al. [4] in which they found that MCPyV-negative specimens, which comprise 20% of cases of MCC, were associated with a poorer overall survival and a greater likelihood for regional nodal metastasis at the time of initial MCC diagnosis. In an editorial comment, DeCaprio [33] offers that virally-induced cancer cells may possess a simpler and less virulent genome, or that viral interference in host cell signaling mechanisms may render the transformed cells more susceptible to immune surveillance, unlike the cases in our series.

Merkel cell carcinoma spreads to the CNS primarily through the blood. Two of the cases in our series and 74% of the cases from our literature review exhibited hematogenous metastases to the brain. Further CNS dissemination occurred through the cerebrospinal fluid in 17% of cases. Access to the dura and intracranial compartment by MCC occurred through direct tumor extension through the calvarium or skull base in six of the total reported cases (17%). In each instance of transcranial disease, the primary disease occurred on the scalp, face, or head and neck. Wojak and Murali [30] suggest that MCC involving the calvarium may originate not from normal cutaneous Merkel cells, but from aberrant rests of cutaneous tissue within the subperiosteal layer of the skull. Indeed, the patient in Case 3 did not appear to have evidence of cutaneous disease, and the tumor was confined to a subgaleal location. Curiously, extensive bony destruction of the calvarium or skull base does not occur. The pre-operative CT scan of the head from Case 3 in this series shows a very limited osteolytic reaction (Fig. 2c) and at the time of surgery, the resected calvarium was structurally intact. Faye et al. [20] noted no evidence of bone destruction in a case of transcalvarial MCC. Barkdull et al. [34] also observed this phenomenon and proposed that the mechanism of intracranial spread may involve small emissary veins that communicate with the diploic venous channels of the skull. Intracranial spread of disease in these cases is not so much direct extension through tissue as it is hematogenous spread through the local venous drainage basins, analogous to lymphatic spread of disease. In Case 3 of this series, recurrence occurred in the calvarium and dura, contralaterally and non-contiguously with the primary lesion. We speculate that removal of a large portion of the skull redirected the venous drainage pattern, resulting in contralateral disease that had the appearance of a lesion arising from the overlying subperiosteal layer.

The development of distant metastatic disease has been viewed as a harbinger of death, for which only palliative care has been offered, and one series reported an 82% death rate within 5 months of the diagnosis of distant metastasis [18]. In our series, one patient died at 7 months, and the other two patients are alive, one with recurrence at 16 months (Case 3) and one with no evidence of disease at 21 months (Case 2). In the cases reviewed in the Table 1, thirty-eight percent of cases from the literature review for which follow-up data were available survived over 1 year, with one patient alive and well at 3 years [35]. These results suggest an aggressive approach to local control of CNS disease in MCC.

Treatment for MCC with CNS involvement has involved resection, chemotherapy, and radiation, but there are no definitive guidelines. We used intracavitary BCNU wafers (Gliadel®) in cases 1 and 2, which appeared to be effective in local CNS control, although the patient in case 1 died of systemic complications of MCC 7 months after the craniotomy and tumor resection. Gliadel® BCNU (3.85% 1, 3-bis-(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea) intracavitary chemotherapy wafers delivers a very high concentration of this mustard gas-related alkylating agent to the tumor site. It is typically used in malignant glioma [40], but has also been demonstrated in a limited pilot study to be effective against local recurrence in a variety of metastatic brain tumors, including melanoma [41]. Furthermore, BCNU/Carmustine has been systemically used in the treatment of MCC [39]. A precedent therefore exists for its use in conjunction with the resection of MCC metastases to the brain to prevent recurrence. Several of the cases from the literature review had CNS recurrence [3, 9, 15, 16, 20]. These reports were reviewed. Time to CNS recurrence was given in four of the cases and was 8 months, 3 months, 2 years, and 10 months. The mean recurrence time was 11 ± 9 months. Case 3 from our series had calvarial and dural recurrence at 16 months after craniectomy, although Gliadel wafers were not indicated for this case of extra-axial disease. We note that our treatment strategy using BCNU wafers for intra-axial neurometastatic disease is anecdotal. There is insufficient evidence to suggest a treatment standard for neurometastatic MCC, but based on the favorable response of this patient and the treatment rationale, we believe that the use of BCNU wafers should be considered a viable treatment option.

In summary, neurometastatic MCC may be emerging as a more common entity than previously thought. CNS involvement is usually intraparenchymal, but may occur through direct extension from a lesion and through CSF dissemination. A literature review revealed 33 neurometastatic MCC cases over twenty-three years. To this number, we add three cases that presented within 1 year at a single institution. Intracavitary BCNU may help prevent local recurrence. The succession of cases we encountered in a short time and the relatively favorable outcomes in one of the cases calls attention to neurometastatic MCC and suggests an aggressive approach to local control of CNS disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Stephen M. Griffey of the Comparative Pathology Laboratory at UC Davis for the polyoma virus analysis. We thank Ms. Christi DeLemos for her administrative assistance and Dr. John Bishop for reviewing the manuscript. We thank Drs. William Mendenhall and Susan J. Knox for responding to inquiries on follow-up from their case reports. Financial support for this project was from the Department of Neurological Surgery at UC Davis.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Allen PJ. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300–2309. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, Mostaghimi A, Wang LC, Peñas PF, Nghiem P. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1152586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sihto H, Kukko H, Koljonen V, Sankila R, Bohling T, Joensuu H. Clinical factors associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus infection in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:938–945. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wick MR, Goellner JR, Scheithauer BW, Thomas JR, Sanchez NP, Schroeter AL. Primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the skin (Merkel cell tumors). A clinical, histologic, and ultrastructural study of thirteen cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1983;79:6–13. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/79.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Straka JA, Straka MB. A review of Merkel cell carcinoma with emphasis on lymph node disease in the absence of a primary site. Am J Otolaryngol. 1997;18:55–65. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(97)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snodgrass SM, Landy H, Markoe AM, Feun L. Neurologic complications of Merkel cell carcinoma. J Neurooncol. 1994;22:231–234. doi: 10.1007/BF01052924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Small KW, Rosenwasser GO, Alexander E, Rossitch G, Dutton JJ. Presumed choroidal metastasis of Merkel cell carcinoma. Ann Ophthalmol. 1990;22:187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma D, Flora G, Grunberg SM. Chemotherapy of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: case report and review of the literature. Am J Clin Oncol. 1991;14:166–169. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199104000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matula C, Roessler K, Burian M, Schuster H, Trattnig S, Hainfellner JA, Budka H. Primary neuroendocrine (merkel cell) carcinoma of the anterior skull base. Skull Base Surg. 1997;7:151–158. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1058607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manome Y, Yamaoka R, Yuhki K, Hano H, Kitajima T, Ikeuchi S. Intracranial invasion of neuroendocrine carcinoma: a case report. Neurol surg. 1990;18:483–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Litofsky NS, Smith TW, Megerian CA. Merkel cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal invading the intracranial compartment. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998;19:330–334. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(98)90008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kroll MH, Toker C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin: further clinicopathologic and morphologic study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1982;106:404–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knox SJ, Kapp DS. Hyperthermia and radiation therapy in the treatment of recurrent Merkel cell tumors. Cancer. 1988;62:1479–1486. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19881015)62:8<1479::AID-CNCR2820620806>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikawa F, Kiya K, Uozumi T, Yuki K, Takeshita S, Hamasaki O, Arita K, Kurisu K. Brain metastasis of Merkel cell carcinoma. Case report and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 1999;22:54–57. doi: 10.1007/s101430050010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hitchcock CL, Bland KI, Laney RG, Franzini D, Harris B, Copeland EM. Neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the skin. Its natural history, diagnosis, and treatment. Ann Surg. 1988;207:201–207. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198802000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grosh WW, Giannone L, Hande KR, Johnson DH. Disseminated Merkel cell tumor. Treatment with systemic chemotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1987;10:227–230. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198706000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goepfert H, Remmler D, Silva E, Wheeler B. Merkel cell carcinoma (endocrine carcinoma of the skin) of the head and neck. Arc otolaryngol. 1984;110:707–712. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1984.00800370009002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feletti A, Marton E, Rossi S, Canal F, Longatti P, Billeci D. Pituitary metastasis of Merkel cell carcinoma. J Neurooncol. 2010;97:295–299. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-0025-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faye N, Lafitte F, Martin Duverneuil N, Guillevin R, Teriitehau C, Cordoliani YS, Chiras J. Merkel cell tumor: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Neuroradiol. 2005;32:138–141. doi: 10.1016/S0150-9861(05)83129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eftekhari F, Wallace S, Silva EG, Lenzi R. Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: imaging and clinical features in 93 cases. Br J Radiol. 1996;69:226–233. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-69-819-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meland NB, Jackson IT. Merkel cell tumor: diagnosis, prognosis, and management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77:632–638. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198604000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giannone L, Johnson DH, Grosh WW, Davis BW, Marangos PJ, Greco FA. Serum neuron-specific enolase in metastatic Merkel cell tumors. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1985;13:357–362. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950130611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang CK, Toker C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin: an ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1978;42:2311–2321. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197811)42:5<2311::AID-CNCR2820420531>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halata Z, Grim M, Bauman KI. Friedrich Sigmund Merkel and his “Merkel cell”, morphology, development, and physiology: review and new results. Anat Record A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2003;271:225–239. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhan FQ, Packianathan VS, Zeitouni NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: a review of current advances. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:333–339. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodgson NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:1–4. doi: 10.1002/jso.20167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sibley RK, Rosai J, Foucar E, Dehner LP, Bosl G. Neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the skin. A histologic and ultrastructural study of two cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1980;4:211–221. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198006000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yiengpruksawan A, Coit DG, Thaler HT, Urmacher C, Knapper WK. Merkel cell carcinoma. Prognosis and management. Arch surg. 1991;126:1514–1519. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410360088014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wojak JC, Murali R. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma presenting in the calvarium: case report. Neurosurg. 1990;26:137–139. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199001000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voog E, Biron P, Martin JP, Blay JY. Chemotherapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;85:2589–2595. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990615)85:12<2589::AID-CNCR15>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang DT, Mancuso AA, Riggs CE, Mendenhall WM. Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin with leptomeningeal metastases. Am J Otolaryngol. 2005;26:210–213. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeCaprio JA. Does detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma provide prognostic information? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:905–907. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barkdull GC, Healy JF, Weisman RA. Intracranial spread of Merkel cell carcinoma through intact skull. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113:683–687. doi: 10.1177/000348940411300901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alexander E, Rossitch E, Small K, Rosenwasser GO, Abson P. Merkel cell carcinoma. Long term survival in a patient with proven brain metastasis and presumed choroid metastasis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1989;91:317–320. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(89)90007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dudley TH, Moinuddin S. Cytologic and immunohistochemical diagnosis of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma in cerebrospinal fluid. Am J Clin Pathol. 1989;91:714–717. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/91.6.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eggers SD, Salomao DR, Dinapoli RP, Vernino S. Paraneoplastic and metastatic neurologic complications of Merkel cell carcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:327–330. doi: 10.4065/76.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Cicco L, Vavassori A, Jereczek-Fossa BA, Pruneri G, Catalano G, Ferrari AM, Orecchia R. Lymph node metastases of Merkel cell carcinoma from unknown primary site: report of three cases. Tumori. 2008;94:758–761. doi: 10.1177/030089160809400522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taxy JB, Ettinger DS, Wharam MD. Primary small cell carcinoma of the skin. Cancer. 1980;46:2308–2311. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19801115)46:10<2308::AID-CNCR2820461030>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westphal M, Ram Z, Riddle V, Hilt D, Bortey E. Gliadel wafer in initial surgery for malignant glioma: long-term follow-up of a multicenter controlled trial. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2006;148:269–275. doi: 10.1007/s00701-005-0707-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ewend MG, Brem S, Gilbert M, Goodkin R, Penar PL, Varia M, Cush S, Carey LA. Treatment of single brain metastasis with resection, intracavity carmustine polymer wafers, and radiation therapy is safe and provides excellent local control. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3637–3641. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]