Membrane surface charge dictates the structure and function of the epithelial Na+/H+ exchanger

This study provides evidence for the epithelial Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE3)-activity to be regulated by charge interactions of its cytosolic domain with membrane phospholipids. The paper therefore expands and generalizes a scheme similarly proposed for inwardly rectifying potassium channels.

Keywords: Na+/H+ exchange, pH regulation, surface charge

Abstract

The Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 plays a central role in intravascular volume and acid–base homeostasis. Ion exchange activity is conferred by its transmembrane domain, while regulation of the rate of transport by a variety of stimuli is dependent on its cytosolic C-terminal region. Liposome- and cell-based assays employing synthetic or recombinant segments of the cytosolic tail demonstrated preferential association with anionic membranes, which was abrogated by perturbations that interfere with electrostatic interactions. Resonance energy transfer measurements indicated that segments of the C-terminal domain approach the bilayer. In intact cells, neutralization of basic residues in the cytosolic tail by mutagenesis or disruption of electrostatic interactions inhibited Na+/H+ exchange activity. An electrostatic switch model is proposed to account for multiple aspects of the regulation of NHE3 activity.

Introduction

The (re)absorption of sodium, water and bicarbonate by the intestine and renal tubules is stringently regulated in order to maintain systemic fluid and pH homoeostasis. The exchange of Na+ for H+ across the apical membrane of renal and intestinal epithelia is central to these processes. This electroneutral countertransport of cations is undertaken primarily by NHE3, the predominant Na+/H+ exchanger isoform expressed apically in these epithelia (Schultheis et al, 1998; Woo et al, 2003). NHE3, which is restricted to apical and sub-apical membranes of epithelial cells, consists of an N-terminal domain composed of 12 membrane-spanning helices and a long cytosolic C-terminal tail of ≈400 residues. While the transmembrane domain mediates the cation exchange reaction, the cytosolic tail is thought to regulate the process, conferring responsiveness to hormones such as aldosterone, angiotensin II, dopamine, somatostatin and parathyroid hormone. The exquisite sensitivity of NHE3 to changes in osmolarity and pH, which is critical for systemic volume and acid–base homoeostasis, is similarly attributed to the C-terminus of the protein (Levine et al, 1993; Cabado et al, 1996; Zizak et al, 2000). This remarkable array of regulatory functions is made possible by the intimate interaction of NHE3 with several ancillary proteins, including CHP, ezrin, NHERFI/II and calmodulin-dependent kinase (Donowitz and Li, 2007).

NHE3 activity is also markedly influenced by the phospholipid composition of the membrane (Lee-Kwon et al, 2003). Na+/H+ exchange is particularly sensitive to the phosphoinositide content (Aharonovitz et al, 2000). Indeed, the acute inhibition of transport caused by ATP depletion (Aharonovitz et al, 1999) is likely caused, at least in part, by the accompanying depletion of polyphosphoinositides. Because phosphoinositides are polyanionic, contributing disproportionately to the surface charge, we considered the possibility that the tail of NHE3 might interact electrostatically with the inner aspect of the plasma membrane, thereby altering its disposition and possibly also its activity. To this end, we perused the primary sequence of NHE3 and modeled the structure of its cytosolic domain (residues 451–831) using the YASSPP algorithm (Karypis, 2006). Three regions in the juxta-membrane domain (residues 472–492, 497–557 and 645–665) are predicted to be α helical. Of note, these helices are amphiphilic displaying both cationic and hydrophobic side chains. In other systems, such structures have a marked tendency to partition into anionic lipid bilayers (Roy et al, 2000; Zasloff, 2002). Like most of the tail, regions between these sections are predicted to be unstructured. The flexibility of such unstructured regions could facilitate the simultaneous interaction of multiple polycationic stretches with the membrane.

Recent determinations of the surface charge of intracellular membranes have found the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane to be the most highly anionic (Holthuis and Levine, 2005; McLaughlin and Murray, 2005; Yeung et al, 2008). This finding, together with the structural predictions described above, suggests that electrostatic interactions may have an important role in establishing the structure of NHE3 and potentially modulate its function. These considerations prompted us to analyse experimentally if individual domains of the cytosolic tail of NHE3 associate with the plasma membrane and whether such an interaction influences the rate and regulation of Na+/H+ exchange.

Results

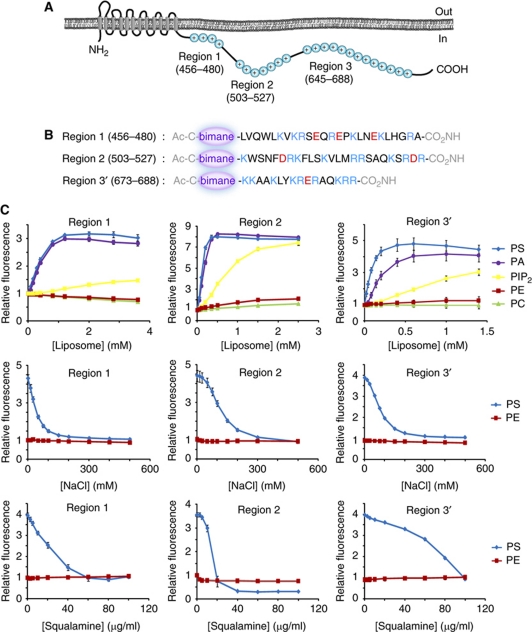

Cationic C-terminal domains of NHE3 bind anionic lipids in vitro

Three particularly cationic regions identified in the C-terminal domain of NHE3 were selected for detailed analysis. These were designated as region 1 (residues 456–480; net charge +4), region 2 (residues 503–527; net charge +7) and region 3 (residues 645–688; net charge +13). A sub-region of particularly high charge density within region 3, named region 3′ (residues 673–688; net charge +8) was also studied separately (Figure 1A). The ability of these domains to associate with anionic bilayers was initially analysed in vitro. To this end, synthetic peptides corresponding to regions 1, 2 and 3′ were generated and conjugated to bimane via their amino terminus (Figure 1B). The fluorescence of bimane, which is highly sensitive to the dielectric constant of the surrounding environment, is greatly enhanced when the conjugated peptides associate with lipid bilayers. We took advantage of this feature to measure binding of regions 1, 2 and 3′ to increasing concentrations of unilamellar liposomes of defined composition. As shown in Figure 1C, none of these peptides bound significantly to liposomes containing only zwitterionic phospholipids, whether they were composed of 100% phosphatidylcholine (PC) or 20% phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) plus 80% PC. By contrast, introduction of 20% phosphatidylserine (PS), a mole fraction comparable to that of the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane of mammalian cells (Vance and Steenbergen, 2005), promoted avid binding of all three peptides. Association of all three peptides with the PS-containing liposomes was remarkably unchanged at temperatures ranging from +4°C to +40°C, indicating that the enthalpy of the binding reaction is small (Supplementary Figure S1). A similar degree of binding was obtained when using another monoanionic phospholipid, phosphatidic acid (PA), suggesting that the interaction is electrostatic, rather than stereospecific. This conclusion is supported by the experiments in the middle row of Figure 1C; binding of all three synthetic peptides to PS-containing liposomes was gradually decreased as the ionic strength of the medium was elevated, a manoeuvre that had no effect on the fluorescence of peptides added to PE-containing liposomes. Similar results were also obtained when the ionic strength was increased by addition of calcium or lanthanum, except that even lower concentrations of these cations were required, as they are di- and trivalent, respectively (Supplementary Figure S2). In addition, all three regions were displaced from PS-containing liposomes by addition of squalamine (Figure 1C, bottom row) or 1436 (Supplementary Figure S3), cationic aminosterols that insert into membranes, making their surface potential more positive. The structurally related cholesterol, which is uncharged, had little effect on peptide binding (Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 1.

Cationic regions within the C-terminus of NHE3 bind to liposomes composed of anionic lipids. (A) Representation of NHE3 demonstrating the transmembrane domain and the location of the three cationic regions within the tail of NHE3. (B) Structure of the synthetic cationic peptides labeled with bimane. (C) Graphs of relative bimane fluorescence of a fixed concentration of labeled peptide incubated with increasing concentrations of liposomes (top row), NaCl (middle) or squalamine (bottom). Liposomes contained 20 mol% PS (blue), 20 mol% PA (violet), 2 mol% PIP2 (yellow) and 20 mol% PE (red) with the balance being PC. Liposomes containing only PC are shown in green.

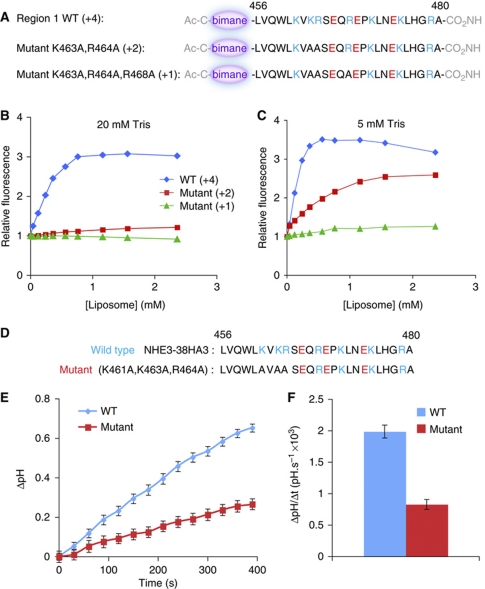

To confirm that an electrostatic interaction mediates the association between the cationic regions of NHE3 and anionic membranes, we generated mutants of region 1 with reduced charge (Figure 2A). Unlike the peptide replicating the native sequence of region 1 (net charge +4), mutant peptides with net charge +2 or +1 bound very poorly to PS-containing bilayers (Figure 2B). Reducing the ionic strength (by lowering the concentration of Tris–Cl from 20 mM, the concentration used in all the preceding experiments, to 5 mM) improved the binding of the mutants to the anionic liposomes (Figure 2C). These observations support the notion that the interaction of the NHE3-derived peptides with PS- or PA-containing membranes is electrostatic in nature. Accordingly, effective peptide binding was also induced by even lower concentrations of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bis-phosphate (PIP2), which bears ≈3.5 negative charges at physiological pH (Figure 1C, top row). Because PS, PIP2 and other anionic lipids co-exist in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane of mammalian cells, the regions of NHE3 corresponding to peptides 1, 2 and 3′ are likely to be attracted strongly to the cytosolic aspect of the plasmalemma.

Figure 2.

Point mutations depress the binding of region 1 to liposomes and the activity of NHE3. (A) Structure of the bimane-labeled synthetic peptides representing wild-type or mutated versions of region 1. The net charge of the peptides is shown in parentheses. (B, C) Graphs of relative bimane fluorescence of a fixed concentration of labeled peptides incubated with increasing concentrations of liposomes in aqueous medium containing 20 mM Tris–Cl (B) or 5 mM Tris–Cl (C). (D) Sequence of cationic region 1 in wild-type NHE3 (top) and in a triple mutant generated to partially depress the charge of this region. (E) Time course of sodium-induced recovery of pHc in acid-loaded MDCK cells expressing either wild-type or the triple mutant form of NHE3. (F) Rate of pHc recovery in cells expressing the wild-type and mutant forms of NHE3, measured over the first 120 s following addition of sodium. Data are mean values±s.e. of 20 individual determinations of each type.

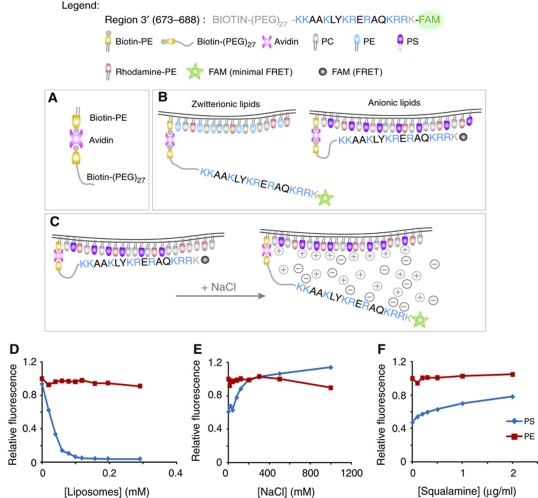

While convenient, the use of soluble synthetic peptides representing defined regions of NHE3 is not a perfect mimic of the interaction of the C-terminus of the protein with the membrane. In situ, the C-terminal domain is permanently tethered to the plasmalemma restricting its diffusion. In this instance, an electrostatic interaction between one or more of the cationic domains and the bilayer would alter the overall topology of the tail, but not its permanence in the membrane. To more accurately assess the effects of the membrane surface charge on NHE3 geometry, we devised a model system where a selected region of the protein (residues 673–688) was tethered to an artificial bilayer through a long (≈15 nm) polyethyleneglycol-based linker. The strategy employed is illustrated in Figure 3. Briefly, avidin was used to bridge biotinylated membrane lipids to the peptide–linker complex, which was itself also biotinylated. The C-terminus of the peptide was additionally conjugated to a fluorescein derivative. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between this green fluorophore and tetramethylrhodamine-labeled lipids inserted into the bilayer was used to estimate the distance between the tethered peptide and the surface of the membrane (see Figure 3C). FRET, measured as donor quenching, was clearly detectable when the peptide was tethered to anionic (20% PS, 78% PC, 1% biotin-PE and 1% rhodamine-PE) liposomes, but marginal when zwitterionic (20% PE, 78% PC, 1% biotin-PE and 1% rhodamine-PE) liposomes were used (Figure 3D). As expected, the FRET-induced quenching was relieved when the ionic strength was elevated (Figure 3E) and also following addition of cationic aminosterols (Figure 3F). These findings are consistent with an electrostatically induced repositioning of the NHE3 peptide, increasing the fraction of time it is juxtaposed to the bilayer.

Figure 3.

In vitro model of lipid binding of a membrane-tethered NHE3 domain. (A) Diagram illustrating the means whereby the cationic peptide was tethered to the liposome. (B) Diagram illustrating the predicted location of the peptide relative to the surface of membranes containing zwitterionic or anionic lipids; note the effect of location on probe fluorescence. (C) Putative mechanism whereby increasing ionic strength disrupts the association of the cationic peptide with anionic membranes and the consequences on probe fluorescence. (D–F) Graphs of relative fluorescence of a fixed concentration of labeled peptide incubated with varying concentrations of ‘acceptor' liposomes (D), NaCl (E) or squalamine (F). Liposomes contained 20 mol% PS (blue) or 20 mol% PE (red) with 80 mol% PC. Fluorescence in (E–F) was normalized to that of PE liposomes.

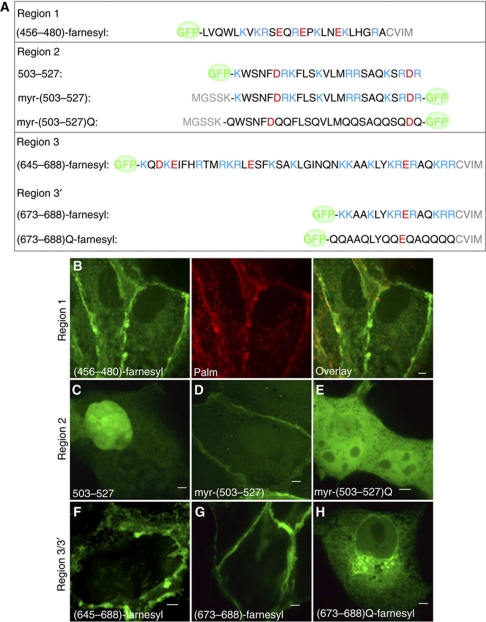

Cationic C-terminal domains of NHE3 bind to the inner surface of the plasma membrane

The preceding in vitro studies attempted to replicate the conditions encountered by the tail of NHE3 in the cell. However, the precise composition of the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane of mammalian cells is neither entirely defined nor is the ionic strength of the cytosol known accurately. To verify that the polycationic segments of the tail of NHE3 bind to the membrane of intact cells, we transfected Madin Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells with plasmids encoding regions 1, 2, 3 or 3′ fused to GFP (see Figure 4A), to facilitate the visualization of the resulting recombinant proteins. As shown in Figure 4C for the GFP-region 2 chimera, fusions of the polycationic regions with GFP accumulate in the nucleus, likely associating with the polyanionic DNA in a manner akin to histones. To circumvent scavenging of the probes by the nucleus and more specifically to study their association with membranes, a hydrophobic moiety was added to the constructs. This was accomplished by inclusion of myristoylation or farnesylation determinants at the N-terminus or C-terminus of the probes, respectively (Figure 4A). Remarkably, all three regions of NHE3 associated preferentially with the plasma membrane (Figure 4B, D, F and G), which was established earlier to have the most negatively charged cytosolic leaflet of all cellular membranes (Okeley and Gelb, 2004; McLaughlin and Murray, 2005; Yeung et al, 2006). Of note, the constructs localized to both the apical and basolateral membranes of polarized MDCK cells (Supplementary Figure S4). The electrostatic biosensor R-pre (Yeung et al, 2006) also partitioned at comparable density into both membranes (Supplementary Figure S4), implying that the surface charge of apical and basolateral membranes is similar, highly negative in both instances. These findings not only support the concept that the cationic regions of NHE3 associate electrostatically with the plasma membrane, but also imply that factors other than charge dictate the asymmetric distribution of the exchangers in epithelial cells.

Figure 4.

Expression of cationic domains of NHE3 in mammalian cells. (A) Diagrammatic depiction of the GFP-tagged constructs generated for expression of individual cationic regions. Prenylation and acylation determinants are shown in grey. (B) Representative image showing the distribution of (456–480)-farnesyl (green) in MDCK cells and its colocalization with the plasmalemmal marker Palm construct (red). (C–H) Representative images displaying the cellular localization of 503–527 (C), myr-(503–527) (D), myr-(503–527)Q (E), (645–688)-farnesyl (F), (673–688)-farnesyl (G) and (673–688)Q-farnesyl (H) in MDCK cells.

An electrostatic interaction drives the association of the acylated chimeras with the plasma membrane was confirmed by mutational analysis. Replacement of the cationic residues in region 2 or 3′ by electroneutral glutamine residues (myristoyl-(503–527)Q and (673–688)Q-farnesyl; see Figure 4A) resulted in distribution of the probes throughout the cell, with no discernible accumulation at the plasma membrane (Figure 4E and H). This finding further indicates that the hydrophobic myristoyl or farnesyl moieties are insufficient to retain the probes at the membrane (Figure 4E) or induce their indiscriminate partition into all cellular membranes (Figure 4H; see also Choy et al, 1999; Henis et al, 2009). However, in conjunction with a cationic motif, they serve to stabilize the probes on membranes with sizable negative surface charge (Roy et al, 2000; Yeung et al, 2008).

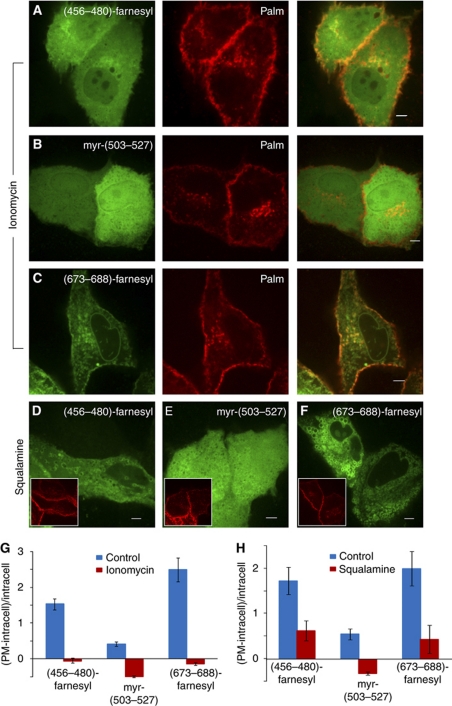

The contribution of an electrostatic component to the association of the lipidated probes with the plasma membrane was validated in several other ways. First, the probes were redistributed throughout the cell and were no longer associated preferentially with the plasma membrane following addition of ionomycin, a calcium ionophore (Figure 5A–C and G). The elevated levels of cytosolic calcium induced by this ionophore collapse the surface charge of the plasma membrane by a combination of three mechanisms: direct shielding, activation of the phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C and loss of inner leaflet PS by activation of the aminophospholipid scramblase (Smeets et al, 1994; Yeung et al, 2006). Maintenance of the integrity of the plasma membrane under these conditions was verified by co-transfection of a farnesylated and diacylated plasma membrane marker, Palm, which attaches to the membrane exclusively by hydrophobic means (Figure 5). Second, the charged lipidated domains also redistributed away from the plasma membrane when cells were treated with squalamine (Figure 5D–F, H; Supplementary Figure S5) or with the synthetic aminosterol 1436 (Supplementary Figure S5). As before, the Palm marker of membrane integrity was unaffected by these treatments (Figure 5; Supplementary Figure S5). Finally, depletion of cellular ATP, which decreases the surface charge by causing net polyphosphoinositide hydrolysis (Figure 7A) and PS scrambling (Seigneuret and Devaux, 1984; Yeung et al, 2006) similarly displaced the probes from the plasmalemma (Supplementary Figure S6).

Figure 5.

Disruption of the electrostatic interaction between cationic constructs and the plasma membrane results in their release and redistribution. (A–C) Representative images of MDCK cells expressing (456–480)-farnesyl (A), myr-(503–527) (B) or (673–688)-farnesyl and the plasmalemmal marker Palm acquired after treatment with ionomycin in the presence of extracellular calcium. (D–F) Representative images of MDCK cells expressing (456–480)-farnesyl (D), myr-(503–527) (E) or (673–688)-farnesyl (F) and Palm after treatment with squalamine. Insets show the distribution of Palm. (G, H) Quantification of the association of the indicated constructs with the plasma membrane, calculated as plasmalemmal (PM) fluorescence minus intracellular fluorescence, divided by intracellular fluorescence, before and after treatment with ionomycin (G) or squalamine (H).

Disruption of the interaction between the cationic domains and the anionic lipids in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane inhibits NHE3 activity

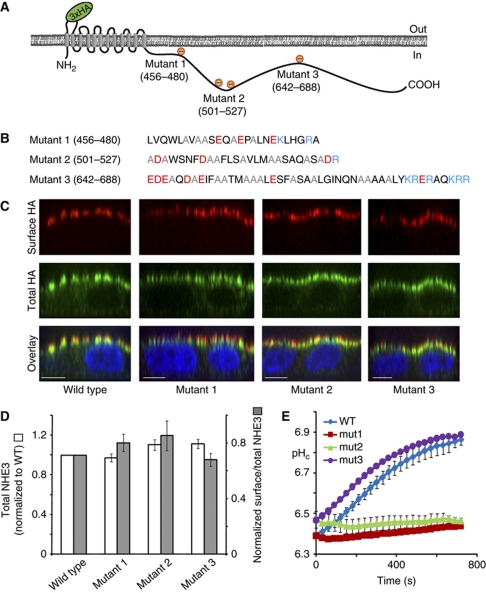

Having established the ability of the cationic domains of NHE3 to associate with the anionic inner surface of the plasmalemma we studied the functional significance of this interaction. To this end, we generated a series of full-length NHE3 constructs with mutations intended to reduce the net charge of the cationic regions. Three different mutants, detailed in Figure 6A and B, were generated. The expression and proper targeting of the mutants were verified first. This was facilitated by introducing a triple-HA epitope in the exofacial loop linking transmembrane domains 1 and 2 of NHE3. Those antiporters that were properly inserted into the apical plasma membrane could be detected selectively when anti-HA antibodies were added to intact (non-permeabilized) cells, while the entire population of cellular NHE3 molecules were visualized and quantified by addition of the antibodies to permeabilized cells. Confluent MDCK cells were used for these experiments to analyse the ability of the mutants to target in a polarized manner in epithelia. Consistent with earlier reports (Alexander et al, 2005), a sizable fraction of the wild-type exchangers was at the apical membrane (47.5±2.1% of total), with the remainder found in sub-apical endomembranes (Figure 6C). Elimination of the cationic charges in regions 1, 2 or 3 had no discernible effect on the expression level or on the ability of the mutant exchangers to target the apical membrane (52.7, 54 and 50.7% at the apical membrane, respectively) (Figure 6C and D).

Figure 6.

Mutation of cationic residues in region 1 or 2 inhibits cation exchange by NHE3. (A, B) Diagrammatic representation of the net charge conferred to regions 1–3 (A) by mutation of cationic residues to alanines, as detailed in (B). (C) Representative XZ reconstructions of surface NHE3 (red), total NHE3 (green) and the nucleus (DAPI/blue) of wild-type and mutant versions of NHE3 expressed in confluent MDCK cells. Size bar=10 μm. (D) Quantification of the total (white bars) and surface (grey bars) expression of three mutants forms of NHE3, relative to the wild type. (E) Sodium-induced recovery of pHc in acid-loaded MDCK cells expressing either wild type or mutants 1–3 of NHE3 (note colour key in the figure inset). Zero second refers to the moment of addition of sodium. Data are mean values±s.e. of at least three experiments of each kind.

Having validated the expression and proper targeting of the mutants, we proceeded to analyse their transport competence. MDCK cells, which lack endogenous apical NHE3 exchangers (Noel et al, 1996), were used for these experiments. The ability of the individual mutants to exchange Na+ for H+ was measured as the rate of recovery of the cytosolic pH (pHc) induced by addition of extracellular Na+ to cells that had been acid loaded by an ammonium pre-pulse (see Materials and methods for details). The small amount of endogenous NHE1 activity was eliminated by performing the experiments in the presence of 10 μM EIPA. As expected, cells expressing wild-type NHE3 responded to the addition of Na+ with a robust alkalinization, which was similarly observed in cells transfected with mutant 3 (Figure 6E), implying that the distal polycationic region 3 is not essential for basal Na+/H+ exchange activity. In sharp contrast, little pH recovery was recorded in cells expressing mutants 1 or 2, despite their normal targeting to the apical membrane (Figure 6C and D). These observations imply that the cationic residues in the more proximal regions 1 and 2 are required for active Na+/H+ exchange.

Our earlier experiments found that even a partial reduction of the charge of peptides mimicking the structure of region 1 markedly decreased their ability to associate with anionic bilayers (Figure 2A–C). We therefore anticipated that comparable changes in net charge would affect the transport activity of the exchangers. This prediction was tested in Figure 2D–F, where an NHE3 construct bearing mutations K461A, K462A and R464A was expressed in MDCK cells. The activity of this mutant was markedly inhibited (Figure 2E and F).

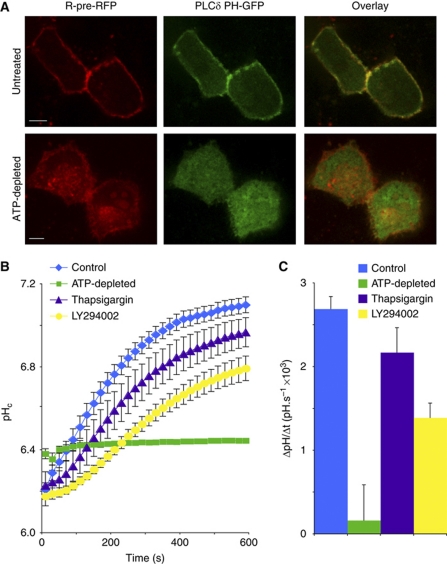

Jointly, the preceding data indicate that elimination of the electrostatic interaction between the tail of NHE3 and the membrane by mutation of cationic domain 1 or 2 is associated with loss of activity. We therefore predicted that depression of the negative surface potential of the membrane would similarly affect the electrostatic interaction and inhibit the activity of the wild-type NHE3. This can be accomplished by depleting the polyanionic phosphoinositides, which contribute disproportionately to the surface charge of the plasmalemma. As illustrated in Figure 7, when the polyphosphoinositide content of Opossum Kidney (OK) cells (which express endogenous NHE3) was reduced by metabolic depletion (middle panels in Figure 7A), the surface charge—assessed using the R-pre-RFP probe (Yeung et al, 2006)—dropped concomitantly (left panels in Figure 7A). An acute and very profound inhibition of NHE3 activity accompanied diminution of the negativity of the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane (Figure 7B and C). A smaller, yet statistically significant inhibition was also noted when formation of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-tris-phosphate was precluded by treatment of the cells with LY294002, an inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (Figure 7B and C).

Figure 7.

Perturbations that disrupt electrostatic interactions with the plasma membrane inhibit NHE3 activity. (A) Subcellular localization of R-pre-RFP (red) and PLCδ-PH-GFP (green) before and after depletion of cellular ATP in MDCK cells. Size bar=5 μm. (B) Sodium-induced recovery of pHc in acid-loaded OK cells (which express endogenous NHE3) that were otherwise untreated (blue), were treated with thapsigargin (purple) or LY294002 (yellow) or subjected to ATP depletion (green). Data are mean values±s.e.m. of at least three determinations of each type. (C) Quantitation of the initial rate of pHc recovery, measured over the first 120 s following addition of sodium in the experiments illustrated in (B).

Even when the intrinsic charge of the protein and that of the membrane are unmodified, the effectiveness of electrostatic interactions can be modulated by altering the ionic strength or by addition of exogenous agents that screen the surface charge. Such manipulations also affect the activity of NHE3. Increasing the ionic strength by exposure of OK cells to hypertonic solutions markedly depressed the rate of Na+/H+ exchange (Supplementary Figure S7), while elevation of cytosolic calcium upon addition of thapsigargin produced a more modest, yet significant effect (Figure 7B and C). Moreover, both squalamine and 1436, the cationic amphiphiles shown above to impair the association of the cationic domains with the membrane (Figure 5; Supplementary Figure S3), have previously been reported to inhibit NHE3 (Akhter et al, 1999).

Discussion

Using a combination of in vitro and in situ approaches, we have shown that three distinct cationic motifs in the tail of NHE3 have the ability to bind to anionic membranes, including the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane. Moreover, altering this interaction by either mutation of the cationic residues to uncharged ones or by modulating the surface charge of the membrane in a predictable manner caused pronounced changes in the rate of Na+/H+ exchange. Based on these observations, we propose that distinct clusters of basic amino acids in the cytosolic C-terminal domain of NHE3 are closely apposed to the lipid bilayer, probably lying parallel and not perpendicular to the plasma membrane, as often depicted. Moreover, we propose that conformational changes caused by the electrostatic interaction have important functional implications.

Our results indicate that conditions which promote dissociation of the cytosolic tail of the exchanger from the bilayer reduce its catalytic activity (Figures 6 and 7). Two mechanisms can be envisaged to cause the inhibition. First, the tail may exert force on neighbouring transmembrane helices, altering their alignment and hence their functionality. In this regard, it is noteworthy that neutralization of the two most proximal cationic clusters (regions 1 and 2) immediately adjacent to the last predicted transmembrane helix exerted profound inhibitory effects on transport activity, whereas neutralization of region 3 had little effect, although we cannot discount that region 3 may exert a regulatory effect in combination with region 1 or 2. These results are consistent with earlier analyses of truncated mutants, which found that deletion of region 3 was inconsequential, while more severe truncations produced profound functional inhibition (Donowitz and Li, 2007). The mechanism suggested above invoking exertion of force on the transmembrane region would be similar to the ‘slide-helix' model proposed for the regulation of the inwardly rectifying K+ (Kir) channel, based on its crystal structure in combination with functional studies (Kuo et al, 2003; Enkvetchakul et al, 2007). As in the case of NHE3, mutations of positively charged residues in the cytosolic tail of Kir led to loss of channel activity, suggesting electrostatic interactions with lipid head-groups (Enkvetchakul et al, 2007). Of note, kinetic studies of NHE3 have identified two distinct functional configurations: an active state and an inactive (or much less active) state, akin to the open and closed states of channels (Hayashi et al, 2002; Alexander et al, 2007). Thus, the position of the tail with respect to the bilayer may dictate the state of activation of the exchanger by modifying its conformation. Alternatively, the tail may physically block access of ions to the cytosolic transport site in a manner that is influenced by its association with the negatively charged bilayer. This situation, analogous to the ‘ball and chain' model proposed for some channels, would not require realignment of the transmembrane domains. Instead, the tail can be envisaged to physically block transport when released from its electrostatic anchorage.

While the transmembrane N-terminal domain of NHE3 mediates the cation exchange reaction, the C-terminal cytosolic tail clearly has a central role in modulating this process. Thus, although active, truncated versions of NHE3 lacking (parts of) the tail lose their responsiveness to physiological regulators including hormones and growth promoters (Levine et al, 1995; Akhter et al, 2000). Remarkably, changes in the electrostatic association of the tail with the inner aspect of the plasma membrane could account for a number of the reported regulatory responses, assuming that attachment of one or more of the cationic regions of the exchanger to the membrane is required for optimal transport activity. The effects of cellular ATP depletion, alterations in cellular osmolarity, and of several small molecules including calmodulin inhibitors and squalamine can all be rationalized by applying an electrostatic model. As illustrated in Figure 7, depletion of cellular ATP causes a drastic drop in the negativity of the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane. This is associated with, and likely caused by, the net dephosphorylation of polyphosphoinositides and the scrambling of PS across the bilayer. The profound inhibition in the rate of Na+/H+ exchange is therefore likely to result from release and rearrangement of the tail with respect to the bilayer and to the transmembrane domains of the transporter. Similarly, the inhibitory effects of squalamine (Akhter et al, 1999) can be explained by its insertion into the membrane, bringing about a collapse in the surface charge, which was verified using the R-pre probe.

Elevation in cytosolic calcium has been reported to inhibit NHE3, although this notion is controversial (Kim et al, 2002; Lee-Kwon et al, 2003; Zachos et al, 2008). The cation could in principle inhibit the exchanger directly or via calmodulin. Elevation of cytosolic calcium can affect the surface potential in at least three different ways: by directly shielding negative charges, by stimulating phosphoinositide hydrolysis and/or by activating the PS scramblase. The combination of these effects can readily account for the observed dissociation of the R-pre surface charge probe and the concomitant inhibition of NHE3.

In both the kidney and the intestine, NHE3 is exposed to solutions of varying osmolarity. The exchanger is known to respond to altered osmolarity with changes in its rate of transport, in a manner that favours ionic and volume homoeostasis (Alexander and Grinstein, 2006). Thus, both cultured cell and renal microperfusion studies found that NHE3 is inhibited by hyperosmolarity (Kapus et al, 1994; Soleimani et al, 1994; Watts et al, 1998; Watts and Good, 1999). Conversely, decreases in cellular osmolarity activate the exchanger (Watts and Good, 1999; Good et al, 2000; Alexander et al, 2007). These observations are interpretable in the light of the electrostatic model of NHE3 regulation. Alterations of medium osmolarity that result in cell volume changes are inevitably accompanied by changes in intracellular ionic strength. Increased ionic strength weakens the electrostatic interaction between the tail of NHE3 and the membrane, as suggested by the data in Figures 1F–H and 3E. The opposite effect is anticipated when the cells swell in response to reduced osmolarity.

Even the reported effects of phosphorylation by PKA or PKC on the activity of NHE3 can be incorporated into a unified model where conformational changes associated with detachment of the tail from the lipid bilayer reduce the rate of cation exchange. PKA catalyses the phosphorylation of NHE3 residues 552 and 605 (Kurashima et al, 1997; Zhao et al, 1999), an event that is necessary but not sufficient for the inhibition of exchanger activity (Kocinsky et al, 2007). Interestingly, ezrin, which together with NHERF is required to bring PKA to the vicinity of the exchanger, also binds directly to NHE3 (Cha et al, 2004) and the binding site overlaps with cationic region 2 (see Figure 1). We propose that upon PKA stimulation the negative charges introduced by phosphorylation favour dissociation of the tail from the membrane in a manner analogous to the ‘electrostatic switch' described by McLaughlin et al for MARCKS and the EGF receptor (McLaughlin and Aderem, 1995; Wang et al, 2002; McLaughlin et al, 2005). Once separated from the membrane, this tail-detached conformation stabilizes an inhibited form of the exchanger. Interestingly, PKA-mediated inhibition of NHE3 is thought to involve not only a reduction in catalytic activity, but also decreased surface expression (Cha et al, 2006). In this regard, the tail-detached form of the exchanger may also serve as a more accessible target for proteins associated with the endocytic and/or exocytic trafficking machinery.

Given the homology between NHE3 and other isoforms of the NHE3, regulation by electrostatic interactions may not be unique to the epithelial isoform. For example, NHE1 displays two cationic regions similar to regions 1 and 2 of NHE3. A region of NHE1 identified as a lipid-interacting domain (LID), which includes cationic region 2, was recently described to associate preferentially with PIP2 and to a lesser degree with PS and PI, compared with other lipids (Wakabayashi et al, 2010). As in the case of NHE3, mutations in the LID of NHE1 depressed its activity (Wakabayashi et al, 2010). Therefore, regulation of ion exchange by electrostatic interactions of cationic motifs with anionic lipids may well be a general feature of members of the NHE family.

In summary, we provided evidence that, rather than extending perpendicularly into the cytosol, the tail of NHE3 approaches the bilayer, maintained in this configuration by electrostatic association with negatively charged head-groups of phospholipids. Confirmation of the actual disposition of the tail with respect to the bilayer will have to await direct structural and molecular dynamic studies of purified, reconstituted NHE3. Moreover, we showed that the cationic motifs that direct the interaction with the membrane are essential for optimal cation exchange activity, as is the maintenance of the uniquely negative surface charge of the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane. Variations in the magnitude of these charges or in their ability to interact can explain a variety of the known regulatory responses of NHE3. While these findings by no means exclude a role of stereospecific interactions with regulatory proteins, the contribution of electrostatic attractions must be taken into account when describing the molecular basis of NHE3 function and regulation.

Materials and methods

Synthetic peptides and liposome binding assays

The synthetic peptides were custom synthesized by Biosynthesis Inc. (Texas). Binding assays of bimane-conjugated peptides to liposomes were performed essentially as in Yeung et al (2006). Briefly, liposomes were first prepared by aliquoting the appropriate amount of lipids (synthetic DOPC, POPS, POPE, POPA, POPE and/or brain PI(4,5)P2, all purchased from Avanti) into a glass tube and drying the solvent, chloroform, under nitrogen. Dried lipids were suspended in 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.2 (unless otherwise specified) using a vortex, before being passed through a liposome extruder (Avestin, Ottawa) with a 100-nm pore-size polycarbonate filter to yield large unilamellar vesicles. Liposomes were composed of DOPC as the bulk lipid with varying amounts of other lipids (20 mol% of either PE, PS or PA, or 2 mol% PI(4,5)P2). For fluorescence measurements, a constant amount of the labeled peptide (∼1 nmol) was added to a glass cuvette (Starna Cells Inc., California) containing a fixed amount of donor PC liposomes suspended in 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer with the indicated concentration of NaCl to vary the ionic strength or squalamine (Moore et al, 1993), 1436 or W7 (Calbiochem) to alter the surface charge and then fluorescence was measured with a Hitachi spectrophotometer F-2500 (excitation at 390 nm and emission at 468 nm). Aliquots of acceptor liposomes were then added to the cuvette and fluorescence was recorded.

For the experiments where the peptides were tethered to liposomes, biotin-PE (1 mol%) was incorporated, the liposomes were pre-treated with avidin and then a fixed amount of the biotinylated peptide added to the liposomes. In these experiments, rhodamine-PE (1 mol%) was also incorporated into the liposomes to serve as a FRET acceptor. FRET was measured as the quenching of FAM (excitation at 495 nm and emission at 525 nm), and the ionic strength and surface charge were altered as above.

Plasmid construction

The region 1, GFP-456–480 farnesyl construct was generated by annealing the forward oligos 5′-TCGAGCCCTGGTGCAGTGGCTGAAGGTGAAGAGGAGCGAGCAGCGTGAGCCGAAGCTCAACGAGAAGCTGCATGGCCGGGCTTGTGTAATTATGTAAG-3′ and the reverse oligos 5′-GATCCTTACATAATTACACAAGCCCGGCCATGCAGCTTCTCGTTGAGCTTCGGCTCACGCTGCTCGCTCCTCTTCACCTTCAGCCACTGCACCAGGGC-3′ together and then ligating the product into the pEGFP-C1 vector (Clontech) digested with the restriction enzymes XhoI and BamHI. The region 2, GFP-503–527 construct was created by annealing the forward oligos 5′-AATTTGAAGTGGTCCAATTTTGATAGGAAGTTCCTCAGCAAAGTCCTCATGAGAAGATCTGCTCAAAAATCTCGAGATCG-3′ and the reverse oligos 5′-GATCCGATCTCGAGATTTTTGAGCAGATCTTCTCATGAGGACTTTGCTGAGGAACTTCCTATCAAAATTGGACCACTTCA-3′ together and then ligating the product into the pEGFP-C1 vector (Clontech) digested with the restriction enzymes EcoRI and BamHI. The region 2, myr-503–527-GFP was created by annealing the forward oligos 5′-TCGAGACCATGGGGAGTAGCAAGAAGTGGTCCAATTTTGATAGGAAGTTCCTCAGCAAAGTCCTCATGAGAAGATCTGCTCAAAAATCTCGAGATCGGATC-3′ and the reverse oligos 5′-GATCGATCCGATCTCGAGATTTTTGAGCAGATCTTCTCATGAGGACTTTGCTGAGGAACTTCCTATCAAAATTGGACCACTTCTTGCTACTCCCCATGGTC-3′ together and then ligating the product into the pEGFP-N1 vector (Clontech) digested with the restriction enzymes XhoI and BamHI. The region 2, myr-503–527Q-GFP was generated by annealing the forward oligos 5′-TCGAGACCATGGGGAGTAGCAAGCAGTGGTCCAATTTTGATCAGCAATTCCTCAGCCAGGTCCTCATGCAACAGTCTGCTCAACAGTCTCAAGATCAGATC-3′ and the reverse oligos 5′-GATCGATCTGATCTTGAGACTGTTGAGCAGACTGTTGCATGAGGACCTGGCTGAGGAATTGCTGATCAAAATTGGACCACTGCTTGCTACTCCCCATGGTC-3′ together and then ligating the product into the pEGFP-N1 vector digested with the restriction enzymes XhoI and BamHI. The region 3, GFP-645–688 farnesyl construct was created by first PCR amplifying the region from cDNA containing the rat-NHE3 construct15 with the forward primer 5′-GACGCAAGATCTAAGCAGGACAAGGAGATCTTCCACAGG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-GACGCAGGATCCTTACATAATTACACACCTCCGCTTCTGTGCGCGCTCCCTC-3′. The BglII and BamHI digested product was then ligated into the pEGFP-C1 vector digested with the same enzymes. The region 3, GFP-673–688 farnesyl was generated by annealing the forward oligos 5′-TCGAGCCAAGAAGGCAGCCAAGCTATATAAGAGGGAGCGCGCACAGAAGCGGAGGTGTGTAATTATGTAAG-3′ and the reverse oligos 5′-GATCCTTACATAATTACACACCTCCGCTTCTGTGCGCGCTCCCTCTTATATAGCTTGGCTGCCTTCTTGGC-3′ together and then ligating the product into the pEGFP-C1 vector digested with the restriction enzymes XhoI and BamHI. The region 3, GFP-673–688Q-farnesyl was generated by annealing the forward oligos 5′-TCGAGCCCAGCAAGCAGCCCAGCTATATCAGCAAGAGCAGGCACAGCAACAGCAATGTGTAATTATGTAAG-3′ and the reverse oligos 5′-GATCCTTACATAATTACACATTGCTGTTGCTGTGCCTGCTCTTGCTGATATAGCTGGGCTGCTTGCTGGGC-3′ together and then ligating the product into the pEGFP-C1 vector digested with the restriction enzymes XhoI and BamHI. Generation of the Palm construct is described in Yeung et al (2006).

The full-length NHE3 constructs with alanine substitutions for the cationic residues in regions 1–3, referred to as mutants 1–3 respectively, and the triple mutant (K461A, K463A and R464A) were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange™ Site-Directed mutagenesis protocol and Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene), or by standard PCR mutagenesis using specific pairs of oligonucleotides containing the desired mutations. The fidelity of all sequences was verified by automated DNA sequencing.

Cell culture and transfection

MDCK type II and OK cells from the ATCC were grown in DMEM/F12 with 5% foetal bovine serum at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator on glass coverslips. AP1 cells stably transfected with NHE3 (D'Souza et al, 1998) were grown in αMEM with 10% foetal bovine serum at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. For live-cell imaging, cells were incubated in Hepes-buffered RPMI 1640 at 37°C. Media and serum were from Wisent Inc. Transient transfection was performed using FuGene6 (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For single plasmid transfection, 1.5–2.0 μg of cDNA and 5 μl of FuGene6 were used. For transfection of two constructs, 1.5 μg of each plasmid and 7 μl of FuGene6 were used.

Image acquisition

Fluorescence images were acquired using spinning-disc confocal microscopy. The systems in use in our laboratory (Quorum) are based on either Leica DM-IRE2 or Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscopes with × 63 or × 100 objectives. The units are equipped with diode-pumped solid-state laser lines (440, 491, 561, 638 and 655 nm; Spectral Applied Research, Richmond Hill, ON), motorized XY stage (ASI) and a piezo focus drive. Images were acquired using either back-thinned, electron-multiplied or conventional cooled charge-couple device cameras (Hamamatsu), driven by the Volocity 4.1.1 software (Improvision).

Image analysis and quantification of fluorescence

Fluorescence images were analysed using Volocity and then exported into Adobe Photoshop CS2 for contrast enhancement and labeling. In Figure 5G, H and Supplementary Figure S5, the quantification of membrane and intracellular fluorescence were performed using the ‘Measurements' feature in Volocity 4.1.0, where objects (regions of interest) were first identified and their mean fluorescence intensity was then measured. Immunostaining of surface and total cellular NHE3, Figure 6C, was performed essentially as described in Alexander et al (2005).

Pharmacological treatments

Ionomycin (10 μM final; Calbiochem) was added to cells bathed in a medium containing 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 and 1 mM CaCl2 (Figure 5A–C). ATP depletion was performed by incubating cells with 200 nM antimycin (Sigma) and 10 mM 2-deoxy-glucose (Sigma) in a glucose-free medium for >30 min. Squalamine (Rao et al, 2000) was added to cells (final concentration 100 μM) incubated in the above medium, Figure 5D and Supplementary Figure S2C. 1436 (Rao et al 2000) was added to cells (final concentration 100 μM) for at least 10 min, Supplementary Figure S2E. LY294002 (Biomol) was added to cells at 50 μM for 20 min. Thapsigargin (Calbiochem) was added at 100 nM for 10 min. Unless otherwise indicated, all treatments and assays were performed at 37°C.

Measurement of Na+/H+ exchange activity

NHE3 activity was assessed as the rate of Na+-induced pHc recovery after an acid load. Dual excitation ratio determinations of the fluorescence of BCECF were used to measure pHc, as previously detailed (Kapus et al, 1994). Briefly, cells were grown to confluence on 25 mm glass cover slips, placed into Attofluor cell chambers and mounted on the stage of the microscope. Next, they were loaded with 5 μg/ml BCECF acetoxymethyl ester in isotonic Na+ buffer: 140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.4 and 5 mM glucose, and pre-pulsed with 50 mM NH4Cl at 37°C for 10 min for subsequent acid loading. Extracellular dye and NH4Cl were then washed away with Na+-free solution and Na+/H+ exchange was initiated by reintroduction of Na+-containing solution. Studies using MDCK cells were performed in the presence of 10 μM EIPA. In studies using the AP1-NHE3 stable cell line, 10 μM of SNARF-5F was employed instead of BCECF. pHc was calibrated by equilibrating the cells with K+-rich media titrated to defined pH values and containing 10 μg/ml nigericin (Thomas et al, 1979). Calibration was performed immediately after the recovery of pHc for each experimental condition tested. Where indicated, the medium was made hypertonic by addition of 150 mM N-methyl-D-glucamine to the isotonic Na+ buffer.

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise indicated, data are presented as mean values±s.e. of the mean of the specified number of determinations. Significance of differences was estimated by analysis of variance or using t-tests, as appropriate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

RTA is supported by a phase II Clinician Scientist award from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) and a KRESCENT New Investigator award, a joint program of the Kidney Foundation of Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Canadian Society of Nephrology. VJ is the recipient of a Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada research fellowship. SG is the recipient of the Pitblado Chair in Cell Biology. The authors' laboratories are supported by CIHR, the Kidney Foundation of Canada and by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Aharonovitz O, Demaurex N, Woodside M, Grinstein S (1999) ATP dependence is not an intrinsic property of Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1: requirement for an ancillary factor. Am J Physiol 276: C1303–C1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharonovitz O, Zaun HC, Balla T, York JD, Orlowski J, Grinstein S (2000) Intracellular pH regulation by Na+/H+ exchange requires phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J Cell Biol 150: 213–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhter S, Cavet ME, Tse CM, Donowitz M (2000) C-terminal domains of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3 are involved in the basal and serum-stimulated membrane trafficking of the exchanger. Biochemistry 39: 1990–2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhter S, Nath SK, Tse CM, Williams J, Zasloff M, Donowitz M (1999) Squalamine, a novel cationic steroid, specifically inhibits the brush-border Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE3. Am J Physiol 276: C136–C144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander RT, Furuya W, Szaszi K, Orlowski J, Grinstein S (2005) Rho GTPases dictate the mobility of the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 in epithelia: role in apical retention and targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 12253–12258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander RT, Grinstein S (2006) Na+/H+ exchangers and the regulation of volume. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 187: 159–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander RT, Malevanets A, Durkan AM, Kocinsky HS, Aronson PS, Orlowski J, Grinstein S (2007) Membrane curvature alters the activation kinetics of the epithelial Na+/H+ exchanger, NHE3. J Biol Chem 282: 7376–7384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabado AG, Yu FH, Kapus A, Lukacs G, Grinstein S, Orlowski J (1996) Distinct structural domains confer cAMP sensitivity and ATP dependence to the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 isoform. J Biol Chem 271: 3590–3599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha B, Kenworthy A, Murtazina R, Donowitz M (2004) The lateral mobility of NHE3 on the apical membrane of renal epithelial OK cells is limited by the PDZ domain proteins NHERF1/2, but is dependent on an intact actin cytoskeleton as determined by FRAP. J Cell Sci 117: 3353–3365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha B, Tse M, Yun C, Kovbasnjuk O, Mohan S, Hubbard A, Arpin M, Donowitz M (2006) The NHE3 juxtamembrane cytoplasmic domain directly binds ezrin: dual role in NHE3 trafficking and mobility in the brush border. Mol Biol Cell 17: 2661–2673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy E, Chiu VK, Silletti J, Feoktistov M, Morimoto T, Michaelson D, Ivanov IE, Philips MR (1999) Endomembrane trafficking of ras: the CAAX motif targets proteins to the ER and Golgi. Cell 98: 69–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donowitz M, Li X (2007) Regulatory binding partners and complexes of NHE3. Physiol Rev 87: 825–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza S, Garcia-Cabado A, Yu F, Teter K, Lukacs G, Skorecki K, Moore HP, Orlowski J, Grinstein S (1998) The epithelial sodium-hydrogen antiporter Na+/H+ exchanger 3 accumulates and is functional in recycling endosomes. J Biol Chem 273: 2035–2043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enkvetchakul D, Jeliazkova I, Bhattacharyya J, Nichols CG (2007) Control of inward rectifier K channel activity by lipid tethering of cytoplasmic domains. J Gen Physiol 130: 329–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good DW, Di Mari JF, Watts BA III (2000) Hyposmolality stimulates Na+/H+ exchange and HCO3− absorption in thick ascending limb via PI 3-kinase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C1443–C1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H, Szászi K, Coady-Osberg N, Orlowski J, Kinsella JL, Grinstein S (2002) A slow pH-dependent conformational transition underlies a novel mode of activation of the epithelial Na+/H+ exchanger-3 isoform. J Biol Chem 277: 11090–11096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henis YI, Hancock JF, Prior IA (2009) Ras acylation, compartmentalization and signaling nanoclusters (Review). Mol Membr Biol 26: 80–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holthuis JC, Levine TP (2005) Lipid traffic: floppy drives and a superhighway. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 209–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapus A, Grinstein S, Wasan S, Kandasamy R, Orlowski J (1994) Functional characterization of three isoforms of the Na+/H+ exchanger stably expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. ATP dependence, osmotic sensitivity, and role in cell proliferation. J Biol Chem 269: 23544–23552 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karypis G (2006) YASSPP: better kernels and coding schemes lead to improvements in protein secondary structure prediction. Proteins 64: 575–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Lee-Kwon W, Park JB, Ryu SH, Yun CH, Donowitz M (2002) Ca2+-dependent inhibition of Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3) requires an NHE3-E3KARP-alpha-actinin-4 complex for oligomerization and endocytosis. J Biol Chem 277: 23714–23724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocinsky HS, Dynia DW, Wang T, Aronson PS (2007) NHE3 phosphorylation at serines 552 and 605 does not directly affect NHE3 activity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F212–F218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Antcliff JF, Rahman T, Lowe ED, Zimmer J, Cuthbertson J, Ashcroft FM, Ezaki T, Doyle DA (2003) Crystal structure of the potassium channel KirBac1.1 in the closed state. Science 300: 1922–1926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurashima K, Yu FH, Cabado AG, Szabó EZ, Grinstein S, Orlowski J (1997) Identification of sites required for down-regulation of Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 activity by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Phosphorylation-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Biol Chem 272: 28672–28679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Kwon W, Kawano K, Choi JW, Kim JH, Donowitz M (2003) Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates brush border Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3) activity by increasing its exocytosis by an NHE3 kinase A regulatory protein-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem 278: 16494–16501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Kwon W, Kim JH, Choi JW, Kawano K, Cha B, Dartt DA, Zoukhri D, Donowitz M (2003) Ca2+-dependent inhibition of NHE3 requires PKC alpha which binds to E3KARP to decrease surface NHE3 containing plasma membrane complexes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 285: C1527–C1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine SA, Montrose MH, Tse CM, Donowitz M (1993) Kinetics and regulation of three cloned mammalian Na+/H+ exchangers stably expressed in a fibroblast cell line. J Biol Chem 268: 25527–25535 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine SA, Nath SK, Yun CH, Yip JW, Montrose M, Donowitz M, Tse CM (1995) Separate C-terminal domains of the epithelial specific brush border Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE3 are involved in stimulation and inhibition by protein kinases/growth factors. J Biol Chem 270: 13716–13725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S, Aderem A (1995) The myristoyl-electrostatic switch: a modulator of reversible protein-membrane interactions. Trends Biochem Sci 20: 272–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S, Murray D (2005) Plasma membrane phosphoinositide organization by protein electrostatics. Nature 438: 605–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S, Smith SO, Hayman MJ, Murray D (2005) An electrostatic engine model for autoinhibition and activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR/ErbB) family. J Gen Physiol 126: 41–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KS, Wehrli S, Roder H, Rogers M, Forrest JN Jr, McCrimmon D, Zasloff M (1993) Squalamine: an aminosterol antibiotic from the shark. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 1354–1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel J, Roux D, Pouyssegur J (1996) Differential localization of Na+/H+ exchanger isoforms (NHE1 and NHE3) in polarized epithelial cell lines. J Cell Sci 109 (Part 5): 929–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okeley NM, Gelb MH (2004) A designed probe for acidic phospholipids reveals the unique enriched anionic character of the cytosolic face of the mammalian plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 279: 21833–21840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao MN, Shinnar AE, Noecker LA, Chao TL, Feibush B, Snyder B, Sharkansky I, Sarkahian A, Zhang X, Jones SR, Kinney WA, Zasloff M (2000) Aminosterols from the dogfish shark Squalus acanthias. J Nat Prod 63: 631–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy MO, Leventis R, Silvius JR (2000) Mutational and biochemical analysis of plasma membrane targeting mediated by the farnesylated, polybasic carboxy terminus of K-ras4B. Biochemistry 39: 8298–8307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultheis PJ, Clarke LL, Meneton P, Miller ML, Soleimani M, Gawenis LR, Riddle TM, Duffy JJ, Doetschman T, Wang T, Giebisch G, Aronson PS, Lorenz JN, Shull GE (1998) Renal and intestinal absorptive defects in mice lacking the NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger. Nat Genet 19: 282–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigneuret M, Devaux PF (1984) ATP-dependent asymmetric distribution of spin-labeled phospholipids in the erythrocyte membrane: relation to shape changes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81: 3751–3755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets EF, Comfurius P, Bevers EM, Zwaal RF (1994) Calcium-induced transbilayer scrambling of fluorescent phospholipid analogs in platelets and erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1195: 281–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani M, Bookstein C, McAteer JA, Hattabaugh YJ, Bizal GL, Musch MW, Villereal M, Rao MC, Howard RL, Chang EB (1994) Effect of high osmolality on Na+/H+ exchange in renal proximal tubule cells. J Biol Chem 269: 15613–15618 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JA, Buchsbaum RN, Zimniak A, Racker E (1979) Intracellular pH measurements in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells utilizing spectroscopic probes generated in situ. Biochemistry 18: 2210–2218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance JE, Steenbergen R (2005) Metabolism and functions of phosphatidylserine. Prog Lipid Res 44: 207–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi S, Nakamura TY, Kobayashi S, Hisamitsu T (2010) Novel phorbol ester-binding motif mediates hormonal activation of Na+/H+ exchanger. J Biol Chem 285: 26652–26661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Gambhir A, Hangyás-Mihályné G, Murray D, Golebiewska U, McLaughlin S (2002) Lateral sequestration of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate by the basic effector domain of myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate is due to nonspecific electrostatic interactions. J Biol Chem 277: 34401–34412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts BA III, Di Mari JF, Davis RJ, Good DW (1998) Hypertonicity activates MAP kinases and inhibits HCO−3 absorption via distinct pathways in thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol 275: F478–F486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts BA III, Good DW (1999) Hyposmolality stimulates apical membrane Na+/H+ exchange and HCO3− absorption in renal thick ascending limb. J Clin Invest 104: 1593–1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo AL, Noonan WT, Schultheis PJ, Neumann JC, Manning PA, Lorenz JN, Shull GE (2003) Renal function in NHE3-deficient mice with transgenic rescue of small intestinal absorptive defect. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F1190–F1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung T, Gilbert GE, Shi J, Silvius J, Kapus A, Grinstein S (2008) Membrane phosphatidylserine regulates surface charge and protein localization. Science 319: 210–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung T, Ozdamar B, Paroutis P, Grinstein S (2006) Lipid metabolism and dynamics during phagocytosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol 18: 429–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung T, Terebiznik M, Yu L, Silvius J, Abidi WM, Philips M, Levine T, Kapus A, Grinstein S (2006) Receptor activation alters inner surface potential during phagocytosis. Science 313: 347–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachos NC, Hodson C, Kovbasnjuk O, Li X, Thelin WR, Cha B, Milgram S, Donowitz M (2008) Elevated intracellular calcium stimulates NHE3 activity by an IKEPP (NHERF4) dependent mechanism. Cell Physiol Biochem 22: 693–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zasloff M (2002) Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415: 389–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Wiederkehr MR, Fan L, Collazo RL, Crowder LA, Moe OW (1999) Acute inhibition of Na+/H+ exchanger NHE-3 by cAMP. Role of protein kinase a and NHE-3 phosphoserines 552 and 605. J Biol Chem 274: 3978–3987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zizak M, Cavet ME, Bayle D, Tse CM, Hallen S, Sachs G, Donowitz M (2000) Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 has 11 membrane spanning domains and a cleaved signal peptide: topology analysis using in vitro transcription/translation. Biochemistry 39: 8102–8112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.