Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this investigation was to compare three types of treatment for binge eating disorder to determine the relative efficacy of self-help group treatment compared to therapist-led and therapist-assisted group cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Method

A total of 259 adults diagnosed with binge eating disorder were randomized to wait-list or 20 week group treatment that was therapist-led, therapist-assisted, or self-help. Binge eating as measured by the Eating Disorder Examination was assessed at baseline, post-treatment, 6- and 12 month follow-up and outcome was determined using logistic regression and analysis of covariance (intention-to-treat).

Results

At end of treatment, the therapist-led (51.7%) and the therapist-assisted (33.3%) conditions had higher binge eating abstinence rates than the self-help (17.9%) and wait-list (10.1%) conditions. No differences in abstinence rates were observed at either follow-up assessment. The therapist-led condition also showed more reductions in binge eating at post-treatment and follow-up compared to the self-help condition, and treatment completion rates were higher in the therapist-led (88.3%) and wait-list (81.2%) conditions than the therapist-assisted (68.3%) and the self-help (59.7%) conditions.

Conclusions

Therapist-led group cognitive-behavioral treatment for binge eating disorder led to higher binge eating abstinence rates, greater reductions in binge eating frequency, and lower attrition at the end of treatment compared to group self-help treatment. Although these findings indicate that therapist delivery of group treatment is associated with better short-term outcome and less attrition than self-help treatment, the lack of group differences at follow-up suggests that self-help group treatment may be a viable alternative to therapist-led interventions. (Clinical Trials Registration: Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder, #NCT00041743; http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00041743?term=00041743&rank=1)

Binge eating disorder is characterized by binge eating episodes, frequent comorbid obesity with associated medical problems (1, 2), high rates of co-occurring psychiatric disorders (3), and psychosocial impairment (4). Several psychological treatments have been found to be helpful in treating this condition (5), including cognitive-behavioral therapy (6, 7), interpersonal therapy (6), dialectical behavior therapy (8), and behavioral weight loss (9). Although medications have been shown to reduce binge eating frequency in several studies (10, 11, 12), pharmacological interventions appear to be less efficacious than evidence-based psychotherapy and have not been observed to improve remission rates when combined with cognitive behavioral therapy (7).

In an attempt to develop less costly treatments that can be more easily disseminated, several investigations have found that cognitive-behavioral and psychoeducational techniques administered in self-help (13) or guided self-help formats have led to improvements in binge eating in those with binge eating disorder (14-17). In all but one of these studies (17), these self-help interventions were administered individually. However, most psychotherapy studies for individuals with binge eating disorder have been conducted using group modalities. The administration of self-help treatment in a group setting has a number of advantages including further reductions in cost, the potential for broader dissemination, and interpersonal support for group members. In examining the potential utility of group self-help for the treatment of binge eating disorder, our preliminary investigation found that a group self-help intervention was comparable to therapist-led and therapist-assisted group cognitive-behavior psychotherapy at post-treatment (18) and follow-up (17). The aim of the current investigation was to compare therapist-led and self-help group cognitive-behavioral treatment for binge eating and associated symptoms, as well as to examine the viability and potential efficacy of therapist-assisted and partial self-help group treatment.

Method

Participants and Recruitment

The sample included 259 adults (n = 227 females, 87.6%; n = 32 males, 12.4%) recruited from two Midwestern clinical sites in the USA (one each in Minnesota and North Dakota). Potential participants were recruited from the community using advertisements as well as referrals from local eating disorder treatment clinics and other health professionals. For inclusion, participants were required to meet full criteria for DSM-IV binge eating disorder (19) as assessed by the Eating Disorder Examination (20) and have a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy or lactation; lifetime diagnosis of bipolar or psychotic disorder; current diagnosis of substance abuse or substance dependence; medical or psychiatric instability including acute suicide risk; current psychotherapy; or current participation in a formal weight loss program. Participants on a stable dose of antidepressant medication for a minimum of six weeks were allowed to participate.

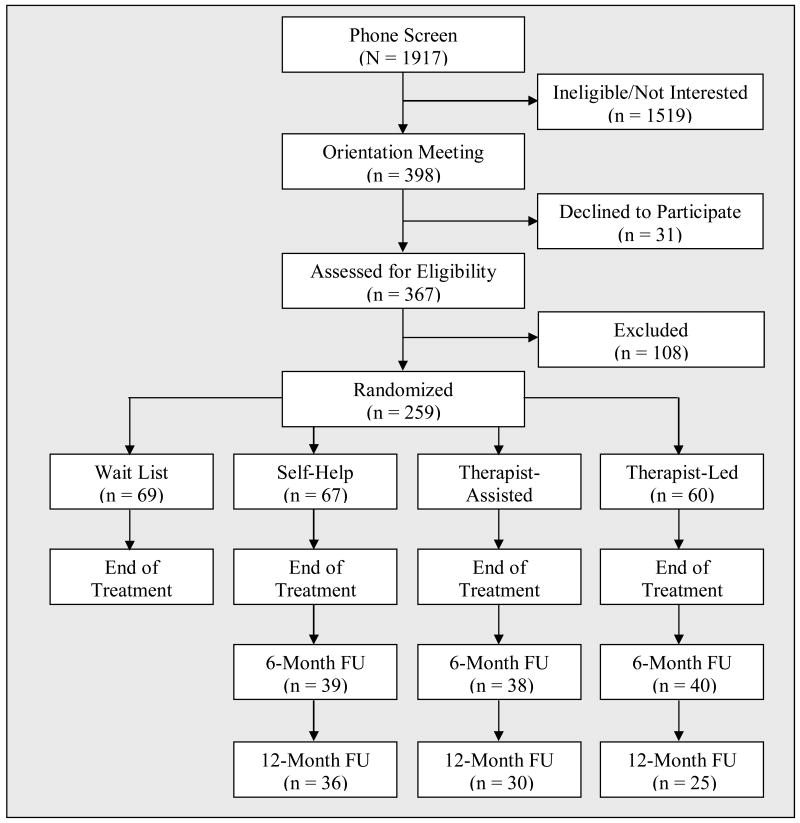

Of the 1917 individuals screened by phone, 1519 were ineligible or not interested in participating (see Figure 1). Three hundred and ninety-eight attended initial orientation meetings, of whom 367 were assessed by interview. Of that group, 108 were excluded or declined to participate, resulting in 259 who were enrolled in the study.

Figure 1. Participant Recruitment and Flow.

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at both sites. Written informed consent was obtained during the orientation meeting after the study had been described to potential participants in detail.

Assessment

The primary outcome measure was the frequency of binge eating episodes as measured by the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE; 20) at baseline, post-treatment, and follow-up assessments. Eating pathology was also assessed using the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ; 21). Additional secondary outcome measures included BMI, the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self-Report (IDS-SR; 22), the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Questionnaire (23), and the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQOL; 24). Participants completed all of these measures at baseline, post-treatment, 6-month follow-up, and 12-month follow-up.

Experienced graduate level assessors conducted the interviews and were blind to participant randomization. Throughout the study, assessors met in person and communicated between sites by teleconference and e-mail in order to prevent drift. All assessment interviews were audiotaped. Inter-rater reliability ratings were conducted on a random sample (20%) of Eating Disorder Examination audiotapes. Interrater reliability (based on intraclass correlation coefficients) for the Eating Disorder Examination subscales and global score ranged from .955 (Shape Concern) to .982 (Restraint).

Treatment

Participants were randomized after completing the assessment protocol. All active treatment consisted of 15 group sessions of 80-minute duration over a 20-week time period, with weekly sessions for the first 10 weeks and bi-weekly sessions for the remaining 10 weeks (average group size = 6.0, range = 2-11). Content of all three active treatment conditions was identical and varied only by treatment delivery. Initial sessions focused on behavioral and cognitive interventions, middle sessions emphasized techniques to target associated problems including stress management and body image, and the final two sessions included strategies to prevent relapse (25). Each 80-minute session was divided into two 40 minute segments, with the first half focusing on psychoeducation and the second half focusing on homework review and discussion. All participants in active treatment received identical workbooks and homework assignments in order to standardize the content of treatment.

Participants were randomized by group to one of three active treatments or the wait list control condition by the independent bio-statistician (RDC). An adaptive randomization strategy was used in which the probability of assignment to any treatment condition at a given point in time was inversely related to the relative proportion of participants previously assigned to that condition. Assignment sequence was shielded from all investigators, study personnel, therapists and participants until time of randomization.

Participants randomized to the wait-list control group were informed that they would receive therapist-led group treatment at the end of the 20 week wait-list period. Their data following active treatment were excluded from all analyses.

The therapist-led cognitive-behavioral groups had a doctoral-level psychotherapist provide psychoeducation during the first half of each session and homework review and discussion for the second half. In the therapist-assisted cognitive-behavioral groups, participants watched a psychoeducational videotape (a specific tape was designed for each session) for the first half of each session; for the second half of each session, a doctoral-level psychotherapist joined the group to review homework and lead a discussion. In the self-help group, participants watched a psychoeducational videotape for the first half of each session and led their own homework review and discussion during the second half. Participants in the self-help groups were given comprehensive instructions with detailed guidelines and time allotments for each discussion session. In addition, group members were assigned the role of lead facilitator on a rotating basis. Participants randomized to the wait list condition received therapist-led treatment at the end of the 20-week waiting period. Data collected from the wait list participants after they had received active treatment following the waiting period were not included in these analyses.

Doctoral level therapists were initially trained by didactic and discussion sessions and led a practice group before administering the treatment for this study. Therapists met regularly with the supervisor (CBP) in person and by teleconference to discuss the implementation of the treatment manual, ensure treatment fidelity, and prevent center drift. All group sessions were audiotaped. Several sessions from each therapist-led and therapist-assisted group (106 tapes total) were reviewed by the supervisors (CBP and SJC) and rated on 7- point Likert scale (with 7 being the highest rating). The overall therapist rating was 6.32 (SD = .38) with the following average subscale ratings: adherence (x = 6.19, SD = .93); comprehensiveness (x = 6.00, SD = .86); effective communication (x = 6.58, SD = .62); therapeutic technique (x = 6.46, SD = .69); and rapport (x = 6.40, SD = .55).

Statistical Analyses

Power analysis for the current study was based upon two previous studies conducted by our research group evaluating the effects of psychotherapeutic and self-help treatment (18, 26) on binge eating. Assuming a two-tailed alpha of .05, it was calculated that a sample size of 65 per group (260 total) would provide a power of greater than .99 to detect post-treatment differences in binge eating frequencies between active treatments and the wait-list control and a power of .88 to detect differences between active treatments (27).

Pre-treatment demographic and clinical characteristics were compared across treatment assignment and site using analysis of variance for continuous measures and logistic regression for dichotomous variables. Models included main effects for treatment group and site and a treatment group-by-site interaction.

The primary efficacy analysis was based upon intention-to-treat. In those cases in which there were missing post-treatment or follow-up data, the pre-treatment value was carried forward. Three primary outcome variables obtained from the EDE were evaluated: binge eating episodes in the previous 28 days, binge eating days in the previous 28 days, and abstinence as defined as no binge eating episodes in the past 28 days. Analysis of covariance was used to compare the four treatment groups (including wait-list) on binge eating episodes and days at post-treatment controlling for pre-treatment values, site and gender (based upon pre-treatment differences between groups). Binge eating episodes and days were log-transformed prior to analysis due to positive skew. Pair-wise post-hoc comparisons between groups were based upon covariate-adjusted contrasts using a significance level of .008 (.05/6) at post-treatment and .017 (.05/3) at follow-up assessments. Logistic regression analysis was used to compare the treatment groups on abstinence rates at post-treatment controlling for site and gender.

Results

Participant Characteristics and Randomization

Randomized participants included 227 (87.6%) women and 32 (12.4%) men. The average age of participants was 47.1 (SD=10.4, range=19-65). Most of the participants were Caucasian (96.1%), had a college degree or higher (54.9%), were employed full-time (61.0%), and were taking antidepressant medication (78.8%). The average BMI was 39.0 kg/m2 (SD = 7.8, range = 24.8-72.6).

A total of 69 participants were randomized to the wait-list control condition (31 in Minnesota, 38 in North Dakota), 67 to the self-help condition (15 in Minnesota, 52 in North Dakota), 63 to the therapist-assisted condition (18 in Minnesota, 45 in North Dakota), and 60 to the therapist-led condition (37 in Minnesota, 23 in North Dakota). Table 1 presents baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by treatment group and data collection site. Participants from the Minnesota site were older (F(1,251) = 6.12; p = .014; partial eta-squared = .024) and had significantly higher TFEQ Restraint scores (F(1,229) = 12.21; p = .001; partial eta-squared = .051). The only difference in baseline characteristics between treatment groups was on gender distribution (χ2(3) = 13.97; p = .003; Nagelkerke R2 = .146), where the percent of females in the therapist-led group (100%) was higher than that for wait-list (81.2%) and therapist-assisted (81.0%) groups.

Table 1. Pre-treatment Characteristics by Treatment Group and Site.

| Wait-List | Self-Help | Therapist-Assisted | Therapist-Led | Total Sample | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MN=31/ND=38/Total=69) | (MN=15/ND=52/Total=67) | (MN=18/ND=45/Total=63) | (MN=37/ND=23/Total=60) | (MN=101/ND=158/Total=259) | ||||||

|

Age (mean ± SD) |

MN: | 49.3 ± 8.4 | MN: | 52.1 ± 8.3 | MN: | 50.3 ± 9.1 | MN: | 50.3 ± 9.1 | MN: | 52.1 ± 8.3† |

| ND: | 46.2 ± 12.0 | ND: | 45.6 ± 10.6 | ND: | 47.2 ± 9.0 | ND: | 47.2 ± 9.0 | ND: | 45.6 ± 10.6† | |

| Total: | 47.6 ± 10.6 | Total: | 47.1 ± 10.4 | Total: | 48.1 ± 9.1 | Total: | 48.1 ± 9.1 | Total: | 47.1 ± 10.4 | |

|

Females (n, %) |

MN: | 23 (74.2%) | MN: | 15 (100%) | MN: | 13 (72.2%) | MN: | 37 (100%) | MN: | 88 (87.1%) |

| ND: | 33 (86.8%) | ND: | 45 (86.5%) | ND: | 38 (84.4%) | ND: | 23 (100%) | ND: | 139 (88.0%) | |

| Total: | 56 (81.2%)‡ | Total: | 60 (89.6%) | Total: | 51 (81.0%)‡ | Total: | 60 (100%)‡ | Total: | 227 (87.6%) | |

|

Caucasian (n, %) |

MN: | 29 (93.5%) | MN: | 15 (100%) | MN: | 18 (100%) | MN: | 33 (89.2%) | MN: | 95 (94.1%) |

| ND: | 38 (100%) | ND: | 52 (100%) | ND: | 42 (93.3%) | ND: | 22 (95.7%) | ND: | 154 (97.5%) | |

| Total: | 67 (97.1%) | Total: | 67 (100%) | Total: | 60 (95.2%) | Total: | 55 (91.7%) | Total: | 249 (96.1%) | |

|

Antidepressant Medication (n, %) |

MN: | 25 (80.6%) | MN: | 12 (80.0%) | MN: | 14 (77.8%) | MN: | 33 (89.2%) | MN: | 80 (79.2%) |

| ND: | 28 (73.7%) | ND: | 43 (82.7%) | ND: | 36 (86.0%) | ND: | 22 (95.7%) | ND: | 124 (78.5%) | |

| Total: | 53 (76.8%) | Total: | 55 (82.1%) | Total: | 50 (79.4%) | Total: | 55 (91.7%) | Total: | 204 (78.8%) | |

|

BMI (mean ± SD) |

MN: | 39.8 ± 7.7 | MN: | 35.9 ± 7.7 | MN: | 39.7 ± 9.1 | MN: | 37.9 ± 8.3 | MN: | 38.5 ± 8.2 |

| ND: | 36.7 ± 5.9 | ND: | 38.8 ± 7.0 | ND: | 41.1 ± 8.7 | ND: | 41.3 ± 8.2 | ND: | 39.3 ± 7.6 | |

| Total: | 38.1 ± 6.9 | Total: | 38.2 ± 7.2 | Total: | 40.7 ± 8.8 | Total: | 39.2 ± 8.3 | Total: | 39.0 ± 7.8 | |

|

Objective Binge Days (mean ± SD) |

MN: | 16.9 ± 8.0 | MN: | 16.2 ± 6.9 | MN: | 16.6 ± 7.1 | MN: | 17.0 ± 6.7 | MN: | 16.8 ± 7.1 |

| ND: | 17.3 ± 6.4 | ND: | 16.4 ± 6.9 | ND: | 16.3 ± 6.3 | ND: | 14.2 ± 7.0 | ND: | 16.3 ± 6.6 | |

| Total: | 17.1 ± 7.1 | Total: | 16.4 ± 6.8 | Total: | 16.4 ± 6.5 | Total: | 16.0 ± 6.9 | Total: | 16.5 ± 6.8 | |

|

Objective Binge Episodes (mean ± SD) |

MN: | 22.8 ± 16.1 | MN: | 18.5 ± 10.4 | MN: | 22.2 ± 15.3 | MN: | 27.4 ± 21.2 | MN: | 23.7 ± 17.4 |

| ND: | 23.5 ± 12.3 | ND: | 23.5 ± 14.4 | ND: | 21.8 ± 11.2 | ND: | 20.0 ± 13.2 | ND: | 22.5 ± 12.8 | |

| Total: | 23.1 ± 14.1 | Total: | 22.4 ± 13.7 | Total: | 21.9 ± 12.3 | Total: | 24.6 ± 18.7 | Total: | 23.0 ± 14.8 | |

|

EDE Restraint (mean ± SD) |

MN: | 1.4 ± 1.3 | MN: | 1.9 ± 1.7 | MN: | 1.4 ± 1.1 | MN: | 1.8 ± 1.4 | MN: | 1.6 ± 1.4 |

| ND: | 1.5 ± 1.2 | ND: | 1.7 ± 1.4 | ND: | 1.3 ± 1.1 | ND: | 1.4 ± 1.1 | ND: | 1.5 ± 1.2 | |

| Total: | 1.5 ± 1.2 | Total: | 1.8 ± 1.5 | Total: | 1.3 ± 1.1 | Total: | 1.6 ± 1.3 | Total: | 1.5 ± 1.3 | |

|

EDE Eating Concerns (mean ± SD) |

MN: | 1.7 ± 1.2 | MN: | 2.4 ± 1.1 | MN: | 1.8 ± 1.3 | MN: | 2.4 ± 1.1 | MN: | 2.1 ± 1.2 |

| ND: | 1.8 ± 1.4 | ND: | 1.8 ± 1.3 | ND: | 1.9 ± 1.2 | ND: | 1.6 ± 1.1 | ND: | 1.8 ± 1.3 | |

| Total: | 1.8 ± 1.3 | Total: | 1.9 ± 1.3 | Total: | 1.9 ± 1.2 | Total: | 2.1 ± 1.2 | Total: | 1.9 ± 1.3 | |

|

EDE Shape Concerns (mean ± SD) |

MN: | 3.4 ± 1.1 | MN: | 3.9 ± 0.8 | MN: | 3.2 ± 1.1 | MN: | 4.0 ± 0.9 | MN: | 3.7 ± 1.0 |

| ND: | 3.8 ± 1.1 | ND: | 3.6 ± 1.2 | ND: | 3.2 ± 1.0 | ND: | 3.4 ± 0.7 | ND: | 3.5 ± 1.0 | |

| Total: | 3.6 ± 1.1 | Total: | 3.7 ± 1.1 | Total: | 3.2 ± 1.0 | Total: | 3.8 ± 0.8 | Total: | 3.6 ± 1.0 | |

|

EDE Weight Concerns (mean ± SD) |

MN: | 3.1 ± 0.9 | MN: | 3.5 ± 1.0 | MN: | 3.1 ± 1.1 | MN: | 3.9 ± 1.0 | MN: | 3.4 ± 1.0 |

| ND: | 3.6 ± 1.1 | ND: | 3.4 ± 1.1 | ND: | 3.0 ± 1.2 | ND: | 3.4 ± 1.1 | ND: | 3.3 ± 1.1 | |

| Total: | 3.4 ± 1.0 | Total: | 3.4 ± 1.1 | Total: | 3.0 ± 1.2 | Total: | 3.7 ± 1.0 | Total: | 3.4 ± 1.1 | |

|

EDE Global (mean ± SD) |

MN: | 2.4 ± 0.8 | MN: | 2.9 ± 0.9 | MN: | 2.4 ± 0.8 | MN: | 3.0 ± 0.7 | MN: | 2.7 ± 0.8 |

| ND: | 2.7 ± 0.9 | ND: | 2.6 ± 0.9 | ND: | 2.4 ± 0.8 | ND: | 2.5 ± 0.8 | ND: | 2.6 ± 0.9 | |

| Total: | 2.6 ± 0.9 | Total: | 2.7 ± 0.9 | Total: | 2.4 ± 0.8 | Total: | 2.8 ± 0.8 | Total: | 2.6 ± 0.9 | |

|

IDS-SR (mean ± SD) |

MN: | 26.8 ± 12.9 | MN: | 28.1 ± 11.9 | MN: | 21.9 ± 11.1 | MN: | 26.0 ± 10.4 | MN: | 25.8 ± 11.5 |

| ND: | 26.0 ± 11.8 | ND: | 26.2 ± 11.0 | ND: | 19.8 ± 9.6 | ND: | 24.0 ± 11.8 | ND: | 24.0 ± 11.2 | |

| Total: | 26.4 ± 12.2 | Total: | 26.7 ± 11.2 | Total: | 20.4 ± 10.0 | Total: | 25.2 ± 10.9 | Total: | 24.7 ± 11.3 | |

|

TFEQ Restraint (mean ± SD) |

MN: | 7.2 ± 3.4 | MN: | 8.6 ± 4.1 | MN: | 7.2 ± 3.3 | MN: | 7.7 ± 3.3 | MN: | 7.6 ± 3.4¶ |

| ND: | 6.6 ± 3.0 | ND: | 6.2 ± 3.9 | ND: | 6.0 ± 3.4 | ND: | 5.3 ± 2.9 | ND: | 6.1 ± 3.4¶ | |

| Total: | 6.9 ± 3.2 | Total: | 6.8 ± 4.1 | Total: | 6.4 ± 3.4 | Total: | 6.8 ± 3.3 | Total: | 6.7 ± 3.5 | |

|

TFEQ Disinhibition (mean ± SD) |

MN: | 13.5 ± 2.0 | MN: | 14.0 ± 1.6 | MN: | 13.7 ± 1.5 | MN: | 14.5 ± 1.4 | MN: | 14.0 ± 1.7 |

| ND: | 13.7 ± 2.0 | ND: | 13.7 ± 1.7 | ND: | 13.5 ± 2.0 | ND: | 13.9 ± 1.7 | ND: | 13.7 ± 1.9 | |

| Total: | 13.6 ± 2.0 | Total: | 13.8 ± 1.7 | Total: | 13.6 ± 1.9 | Total: | 14.3 ± 1.5 | Total: | 13.8 ± 1.8 | |

|

TFEQ Hunger (mean ± SD) |

MN: | 9.1 ± 3.6 | MN: | 10.2 ± 3.6 | MN: | 10.1 ± 2.7 | MN: | 9.3 ± 3.4 | MN: | 9.5 ± 3.3 |

| ND: | 9.5 ± 3.6 | ND: | 10.4 ± 2.9 | ND: | 9.7 ± 3.1 | ND: | 9.9 ± 3.1 | ND: | 9.9 ± 3.2 | |

| Total: | 9.3 ± 3.5 | Total: | 10.4 ± 3.1 | Total: | 9.8 ± 3.0 | Total: | 9.5 ± 3.3 | Total: | 9.8 ± 3.2 | |

|

IWQOL-Lite Total (mean ± SD) |

MN: | 56.9 ± 21.7 | MN: | 55.3 ± 26.7 | MN: | 52.5 ± 22.8 | MN: | 54.4 ± 16.5 | MN: | 55.0 ± 20.8 |

| ND: | 53.1 ± 14.1 | ND: | 52.6 ± 19.4 | ND: | 51.7 ± 19.3 | ND: | 51.6 ± 19.4 | ND: | 52.3 ± 18.3 | |

| Total: | 55.3 ± 18.7 | Total: | 53.3 ± 21.4 | Total: | 52.0 ± 20.3 | Total: | 53.4 ± 17.5 | Total: | 53.5 ± 19.4 | |

|

Rosenberg Self-Esteem (mean ± SD) |

MN: | 2.6 ± 1.9 | MN: | 2.8 ± 2.3 | MN: | 1.9 ± 1.8 | MN: | 2.5 ± 1.9 | MN: | 2.5 ± 1.9 |

| ND: | 3.1 ± 2.0 | ND: | 3.3 ± 2.0 | ND: | 2.5 ± 2.0 | ND: | 2.7 ± 1.9 | ND: | 2.9 ± 2.0 | |

| Total: | 2.8 ± 2.0 | Total: | 3.2 ± 2.1 | Total: | 2.3 ± 1.9 | Total: | 2.6 ± 1.9 | Total: | 2.7 ± 2.0 | |

p = .014 for main effect of site (MN > ND)

p = .003 for main effect of treatment group (TL > WL,TA)

p = .001 for main effect of site (MN > ND)

Attrition

Of the 259 participants randomized to treatment or the wait list condition, 192 (74.1%) were assessed at the post-treatment or post-wait list visit (Figure 1). A larger number of participants completed the therapist-led (n = 53; 88.3%) and wait-list (n = 56; 81.2%) conditions than the therapist-assisted (n = 43; 68.3%) and self-help (n = 40; 59.7%) conditions (χ2(3) = 16.50; p = .001). In comparison to those who completed the post-treatment assessment, those who did not complete the assessment were younger (44.4 vs. 47.8 years; F(1,257) = 5.44, p = .020; partial eta-squared = .021), but did not differ on other demographic or clinical characteristics.

Abstinence Rates

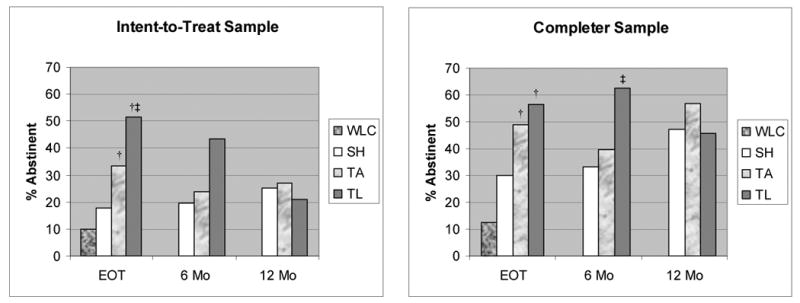

Figure 2 presents the percent of participants abstinent from objective binge eating episodes in the past 28 days at end of treatment, 6-month follow-up, and 12-month follow-up by treatment group based upon intent-to-treat and completer status. Intention-to-treat abstinence rates were as follows: Post-treatment: therapist-led = 51.7%; therapist-assisted = 33.3%; self-help = 17.9%; wait-list = 10.1%; Six-Month Follow-Up: therapist-led = 43.3%; therapist-assisted = 23.8%; self-help = 19.4%, Twelve-Month Follow-Up: therapist-led = 20.8%; therapist-assisted = 27.0%; self-help = 25.4%. Post-treatment abstinence rates were significantly different across treatment groups after controlling for site and gender based upon both intent-to-treat (χ2(3) = 24.19; p < .001) and completer analysis (χ2(3) = 22.28; p < .001). Therapist-led and therapist-assisted groups had significantly (p < .008) higher abstinence rates than the wait list condition for both analyses. In addition, abstinence rates for the therapist-led group were significantly higher than that for self-help based upon intent-to-treat but not the completer analysis. Differences in abstinence rates at 6-month follow-up approached significance for intent-to-treat analysis (χ2(2) = 5.55; p = .062) and reached statistical significance based upon completer analysis (χ2(2) = 6.69; p = .035), with the therapist-led group having significantly higher abstinence rates than the self-help condition (p = .013). No differences between abstinence rates at 12-month follow-up were found for either intent-to-treat (χ2(2) = 2.59; p = .274) or completer (χ2(2) = 1.27; p = .530) analysis. No site differences were observed in abstinence rates.

Figure 2. Abstinence rates by treatment group based upon intent-to-treat and completer samples.

† p < .008 vs.WLC

‡ p < .008 vs. SH

WLC = Wait-list control, SH = Self-help, TA = Therapist-assisted, TL = Therapist-led

EOT = End of treatment, 6 Mo = 6-month follow-up, 12 mo = 12-month follow-up

Binge Eating Frequency

Table 2 presents average objective binge eating days and episodes at baseline, post-treatment, 6-month follow-up, and 12-month follow-up by treatment group based upon intention-to-treat analysis. Significant differences between treatment groups at post-treatment assessment were found for both objective binge eating days (F(3,252) = 14.97; p < .001; partial eta-squared = .151) and episodes (F(3,252) = 15.29; p < .001; partial eta-squared = .154). Post hoc analyses indicated that (1) the therapist-led group had greater reductions in objective binge eating days and episodes than the self-help and wait-list groups, (2) the therapist-assisted group had greater reductions in objective binge eating days and episodes than the wait-list group, and (3) the self-help group had greater reductions in objective binge eating episodes (but not days) than the wait-list group. No significant differences in binge eating frequencies were found between treatment groups at either of the follow-up assessments. No site differences were observed at end of treatment or follow-up.

Table 2. Mean values of primary and secondary outcomes at each assessment by treatment group based upon intent-to-treat sample.

| Measure | Treatment Group | Assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-Treatment | 6-Month FU | 12-Month FU | ||

|

OBE Days1 (mean ± SD) |

Wait List (n = 69) | 17.1 ± 7.1 | 13.5 ± 9.3 | ||

| Self-Help (n = 67) | 16.4 ± 6.8 | 9.6 ± 8.6 | 9.3 ± 8.8 | 9.6 ± 8.9 | |

| Therapist-Assisted (n = 63) | 16.4 ± 6.5 | 7.6 ± 8.4† | 9.6 ± 8.8 | 9.3 ± 8.6 | |

| Therapist-Led (n = 60) | 16.0 ± 6.9 | 4.4 ± 7.3†‡ | 7.4 ± 9.3 | 10.6 ± 9.3 | |

|

OBE Episodes1 (mean ± SD) |

Wait List (n = 69) | 23.1 ± 14.1 | 17.6 ± 14.6 | ||

| Self-Help (n = 67) | 22.4 ± 13.7 | 11.9 ± 13.2† | 11.9 ± 13.8 | 12.4 ± 13.7 | |

| Therapist-Assisted (n = 63) | 21.9 ± 12.3 | 9.7 ± 12.4† | 12.5 ± 13.2 | 12.3 ± 12.9 | |

| Therapist-Led (n = 60) | 24.6 ± 18.7 | 6.3 ± 12.3†‡ | 10.6 ± 14.8 | 16.2 ± 19.4 | |

|

EDE Restraint (mean ± SD) |

Wait List (n = 69) | 1.5 ± 1.2 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | ||

| Self-Help (n = 67) | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | |

| Therapist-Assisted (n = 63) | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 1.1 ± 1.0 | 1.1 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 1.1 | |

| Therapist-Led (n = 60) | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 1.1 ± 1.0† | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 1.6 ± 1.2 | |

|

EDE Eating Concerns (mean ± SD) |

Wait List (n = 69) | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 1.3 ± 1.1 | ||

| Self-Help (n = 67) | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 1.3 ± 1.2 | 1.3 ± 1.2 | |

| Therapist-Assisted (n = 63) | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 1.1 ± 1.1 | 1.2 ± 1.2 | |

| Therapist-Led (n = 60) | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 1.1 ± 1.1 | 1.2 ± 1.3 | 1.6 ± 1.2 | |

|

EDE Shape Concerns (mean ± SD) |

Wait List (n = 69) | 3.6 ± 1.1 | 3.1 ± 1.2 | ||

| Self-Help (n = 67) | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 3.1 ± 1.3 | 3.1 ± 1.4 | 3.0 ± 1.4 | |

| Therapist-Assisted (n = 63) | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 2.6 ± 1.3 | |

| Therapist-Led (n = 60) | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 1.2 | 3.2 ± 1.3 | |

|

EDE Weight Concerns (mean ± SD) |

Wait List (n = 69) | 3.4 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | ||

| Self-Help (n = 67) | 3.4 ± 1.1 | 3.1 ± 1.2 | 3.0 ± 1.3 | 3.0 ± 1.3 | |

| Therapist-Assisted (n = 63) | 3.0 ± 1.2 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 2.5 ± 1.3 | 2.5 ± 1.3 | |

| Therapist-Led (n = 60) | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 1.3 | 3.0 ± 1.2 | 3.3 ± 1.2 | |

|

EDE Global (mean ± SD) |

Wait List (n = 69) | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 0.9 | ||

| Self-Help (n = 67) | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | |

| Therapist-Assisted (n = 63) | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 1.8 ± 0.8† | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 0.9 | |

| Therapist-Led (n = 60) | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | |

|

BMI (mean ± SD) |

Wait List (n = 69) | 38.1 ± 6.9 | 38.3 ± 7.4 | ||

| Self-Help (n = 67) | 38.2 ± 7.2 | 39.1 ± 10.6 | 39.5 ± 14.8 | 38.7 ± 10.6 | |

| Therapist-Assisted (n = 63) | 40.7 ± 8.8 | 40.8 ± 8.5 | 40.6 ± 8.9 | 40.4 ± 8.9 | |

| Therapist-Led (n = 60) | 39.2 ± 8.3 | 40.8 ± 11.7 | 39.8 ± 10.0 | 38.3 ± 8.5 | |

|

IDS-SR (mean ± SD) |

Wait List (n = 67) | 26.4 ± 12.2 | 23.3 ± 10.7 | ||

| Self-Help (n = 64) | 26.7 ± 11.2 | 23.4 ± 13.4 | 25.2 ± 12.8 | 23.8 ± 12.4 | |

| Therapist-Assisted (n = 61) | 20.4 ± 10.0 | 17.7 ± 9.5 | 17.0 ± 9.4 | 17.8 ± 10.0 | |

| Therapist-Led (n = 59) | 25.2 ± 10.9 | 19.8 ± 11.3 | 20.3 ± 11.7 | 20.8 ± 12.0 | |

|

TFEQ Restraint (mean ± SD) |

Wait List (n = 61) | 6.9 ± 3.2 | 7.0 ± 3.5 | ||

| Self-Help (n = 61) | 6.8 ± 4.1 | 7.8 ± 4.4 | 7.8 ± 4.1 | 7.7 ± 3.9 | |

| Therapist-Assisted (n = 56) | 6.4 ± 3.4 | 7.9 ± 3.7 | 7.9 ± 4.3 | 7.1 ± 4.2 | |

| Therapist-Led (n = 59) | 6.8 ± 3.3 | 8.7 ± 3.7 | 8.2 ± 4.2 | 8.1 ± 4.1 | |

|

TFEQ Disinhibition (mean ± SD) |

Wait List (n = 61) | 13.6 ± 2.0 | 13.4 ± 2.1 | ||

| Self-Help (n = 61) | 13.8 ± 1.7 | 12.7 ± 2.3 | 12.6 ± 2.7 | 12.8 ± 2.7 | |

| Therapist-Assisted (n = 56) | 13.6 ± 1.9 | 12.2 ± 2.9† | 11.9 ± 3.0 | 12.7 ± 2.5 | |

| Therapist-Led (n = 59) | 14.3 ± 1.5 | 11.9 ± 3.4† | 12.7 ± 3.3 | 13.0 ± 2.9 | |

|

TFEQ Hunger (mean ± SD) |

Wait List (n = 61) | 9.3 ± 3.5 | 9.0 ± 3.6 | ||

| Self-Help (n = 61) | 10.4 ± 3.1 | 9.9 ± 3.8 | 9.2 ± 3.6 | 9.3 ± 3.3 | |

| Therapist-Assisted (n = 56) | 9.8 ± 3.0 | 8.5 ± 3.5 | 8.2 ± 3.6 | 8.7 ± 3.7 | |

| Therapist-Led (n = 59) | 9.5 ± 3.3 | 8.0 ± 3.8 | 8.1 ± 3.5 | 8.4 ± 3.8 | |

|

IWQOL-Lite Total (mean ± SD) |

Wait List (n = 53) | 55.3 ± 18.7 | 57.0 ± 18.1 | ||

| Self-Help (n = 57) | 53.3 ± 21.4 | 58.6 ± 21.2 | 60.3 ± 23.1 | 58.3 ± 22.8 | |

| Therapist-Assisted (n = 54) | 52.0 ± 20.3 | 58.5 ± 21.4 | 58.8 ± 21.8 | 57.6 ± 22.1 | |

| Therapist-Led (n = 56) | 53.4 ± 17.5 | 58.7 ± 18.4 | 60.1 ± 18.1 | 58.1 ± 20.7 | |

|

Rosenberg Self-Esteem (mean ± SD) |

Wait List (n = 61) | 2.8 ± 2.0 | 2.3 ± 1.7 | ||

| Self-Help (n = 62) | 3.2 ± 2.1 | 3.0 ± 2.2 | 3.0 ± 2.0 | 2.9 ± 1.9 | |

| Therapist-Assisted (n = 59) | 2.3 ± 1.9 | 2.0 ± 1.7 | 2.0 ± 2.0 | 2.2 ± 1.9 | |

| Therapist-Led (n = 59) | 2.6 ± 1.9 | 2.3 ± 1.9 | 2.3 ± 1.9 | 2.2 ± 1.9 | |

Log-transformed prior to analysis. Means and standard deviations are presented in original units.

p < .008 vs. Wait List controlling for baseline value, site, and gender

p < .008 vs. Self-Help controlling for baseline value, site, and gender

Secondary Outcomes

Few differences were found between treatment groups in secondary outcome measures at post-treatment assessment (see Table 2). The therapist-led group experienced significantly greater reductions than the wait-list group on EDE Restraint subscale (F(3,252) = 3.46; p = .017; partial eta-squared = .040) and EDE Global scores (F(3,252) = 4.04; p = .008; partial eta-squared = .046). In addition, both the therapist-assisted and therapist-led groups experienced greater reductions in TFEQ Disinhibition scores than the wait-list group (F(3,230) = 5.78; p = .001; partial eta-squared = .070). No differences in secondary outcome measures including depression, quality of life, and BMI were observed between treatment groups at either follow-up.

Discussion

The results of this investigation indicate that psychoeducational and cognitive-behavioral techniques can be implemented in therapist-led, therapist-assisted, and structured self-help group formats for the treatment of those with binge eating disorder. Although all three active treatments appeared to have better outcome than the wait list control condition on most measures of binge eating, those in the therapist-led group had the highest rate of abstinence and the fewest drop-outs at the end of treatment. No significant differences were found between treatment groups at follow-up on any of the primary or secondary measures of outcome. Although improvements in binge eating were notable, co-occurring symptoms including depression and low self-esteem did not improve more significantly in the active treatment conditions than in the wait list condition and did not differ among the treatments at follow-up. Similar to previous studies that have used cognitive-behavioral and self-help approaches to treat binge eating disorder, body mass index did not change significantly over the course of treatment or follow-up.

These findings suggest that groups for individuals with binge eating disorder with reduced or no therapist involvement may be used as alternative treatments and that psychoeducation for the treatment of binge eating can be delivered in a group format using video or other technology. However, the presence of a therapist may enhance short-term abstinence and reduce the likelihood of participant drop-out. Nonetheless, structured self help groups may be useful in settings in which trained therapists are not available and may improve the dissemination of efficacious treatments for those with binge eating disorder. These findings are also consistent with previous studies of binge eating disorder (28) as well as other areas of behavioral health (29) that self-help approaches are a viable alternative to therapist-delivered treatment.

This study is among the first to examine the delivery of therapist-assisted and self-help interventions to patients with binge eating disorder in a group format. Additional strengths of this investigation include its sample size as well as its rigorously conducted assessment and interventions. Several limitations should be noted. The participants were primarily female, Caucasian, and well-educated, which may limit the generalizability of these findings to broader populations of individuals with binge eating disorder. Also, patients were randomized by group rather than individually. In addition, because the wait-list control group was given treatment at the end of the 20-week waiting period, whether that group would have shown improvement and spontaneous recovery over the course of the follow-up if they had not received treatment is unknown. Without a control group during the follow-up phase, it is impossible to be certain that the active interventions actually yielded long-term treatment effects. Although retaining a longer-term wait list control group raises potential ethical concerns, this possibility warrants consideration is future investigations to demonstrate treatment efficacy. Finally, the self-help group approach used in this investigation was highly structured with significant accountability required for the participants. For this reason, these results are not necessarily reflective of self-help groups in the community that tend to be less structured and more informal.

Future research should seek to enhance abstinence rates in the treatment outcome of patients with binge eating disorder. Because the abstinence rates of this investigation were lower than those using individual approaches to psychotherapy, guided self-help, and self help (14, 15), a larger randomized study comparing individual with group-based self-help is necessary. The drop out rates in this study were also notable, making interpretation of the follow-up data less clear, raising concerns about the acceptability of group based approaches with this intervention, and suggesting that future investigations examine ways to improve attrition through enhanced efficacy and acceptability. In addition, further research is needed to understand the cost effectiveness of these approaches given the fact that therapist-led treatments are generally more expensive than self-help approaches, as well as the use of innovative therapy delivery models to increase the accessibility and dissemination of treatment and the incorporating of these strategies into stepped care designs. Finally, effectiveness trials are needed to examine the extent to which these models can be used in clinical and community settings.

Patient Perspective.

“Ms. B”, a 47 year old married female, reported a 30 year history of binge eating episodes. In her initial assessment for the study, she described having binge eating episodes in which she would eat a an entire pie at one sitting or a half a gallon of ice cream, during which time she experienced a sense of lack of control and a subjective feeling of not being able to stop eating once she started. In addition, Ms. B described these episodes as highly distressing. Ms. B. had tried many diets and formal weight loss programs on her own but always relapsed to binge eating within a few months. Ms. B. denied current or past history of other eating disorder symptoms including self-induced vomiting or abuse of laxatives or diuretics. Ms. B. also described a history of recurrent major depression with an onset during young adolescence.

Ms. B was randomized to the therapist-led condition of the study and attended weekly group sessions. Although she found it difficult at first to write down all of her food intake on the self-monitoring forms, this process became easier after the first month of treatment. By paying close attention to the patterns of binge eating on her food log and “cues” (triggers) that would typically precede these episodes, Ms. B. learned to change her behavior patterns and was able to reduce the frequency of her episodes. Ms. B. also learned about her “thinking patterns” and realized that she tended to view her eating patterns in extremes (for example, not eating any ice cream or eating the entire container). In group sessions, she learned how to change her “self-talk” and found that as a result, she could eat normal portions of food she liked without binge eating. Ms. B. also worked on changing her self-talk patterns to improve her self-esteem. By the end of the treatment, Ms. B. reported infrequent overeating episodes that occurred less than once a week; when these episodes did occur, she experienced a sense of loss of control but did not consume large amounts of food. At the time of her end of treatment assessment, Ms. B. described slight disappointment that she had not lost a significant amount of weight but expressed relief to be free of the binge eating episodes that had caused her such significant distress.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants DK61912, DK 61973, and P30 DK 60456 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, grant K02 MH65919 from the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Neuropsychiatric Research Institute.

The authors thank Drs. Helene Keery, Christianne Lysne, Kathryn Miller, Hal Pickett, Lorraine Swan, and Molly Gill Willer for serving as therapists for this study, and Christine Dittel, Nora Sandager, Heather Beach, Aimee Arikian, Kelly Berg, Tricia Myers, Nancy Monson, Heather Simonich, Melissa Burgard, Kevin Rittenhouse, Macey Furstenau, Lisa Chartier, Erin Venegoni, Andrew Selders, Kathy Lancaster, Shannon Bailey, Joy Johnson-Lind, Jodi Swanson, Traci Kalberer, Jason Hammes, Jennifer Redlin, Maria Frisch, Justin Boseck, and Deborah Roerig for the assistance with coordination, data management, and assessment interviewing.

Footnotes

Presented at the International Conference on Eating Disorders in Barcelona, Spain (June 7-10, 2006) and the Annual Meeting of the Eating Disorders Research Society in Port Douglas, Australia (August 31-September 2, 2006).

Drs. Crosby and Wonderlich report no competing interests. Drs. Mitchell and Peterson receive royalties from Guilford Press. Dr. Crow reports research support from Pfizer, GlaxoSmith Klein, and Ortho McNeill and honoraria from Eli Lilly. Dr. Mitchell reports research support from Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKlein.

References

- 1.Johnson JG, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Health problems, impairment and illness associated with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder among primary care and obstetric gynecology patients. Psychol Med. 2001;31:1455–1466. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bulik CM, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. Medical morbidity in binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34:S39–S46. doi: 10.1002/eat.10204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanovski SZ, Nelson JE, Dubbert BK, Spitzer RL. Association of binge eating disorder and psychiatric comorbidity in obese subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1472–1479. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.10.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilfley DE, Wilson GT, Agras WS. The clinical significance of binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Dis. 2003;34:S96–S106. doi: 10.1002/eat.10209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wonderlich SA, de Zwaan M, Mitchell JE, Peterson C, Crow S. Psychological and dietary treatments of binge eating disorder: conceptual implications. Int J Eat Dis. 2003;34:S58–S73. doi: 10.1002/eat.10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilfley DE, Welch RR, Stein RI, Spurrell EB, Cohen LR, Saelens BE, Dounchis JZ, Frank MA, Wiseman CV, Matt GE. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of overweight individuals with binge-eating disorder. Arch Gen Psych. 2002;59:713–721. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grilo CG, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biol Psych. 2005;57:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Telch CF, Agras WS, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:1061–1065. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcus MD, Wing RR, Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavioral treatment of binge eating vs behavioral weight control in the treatment of binge eating disorder. Ann Behav Med. 1995;17(suppl):S090. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudson JI, McElroy SL, Raymond NC, Crow S, Keck PE, Jr, Carter WP, Mitchell JE, Strakowski SM, Pope HG, Jr, Coleman BS, Jonas JM. Fluvoxamine in the treatment of binge eating disorder: A multicenter placebo-controlled double-blind trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1756–1762. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McElroy SL, Casuto LS, Nelson EB, Lake KA, Soutullo CA, Keck PE, Jr, Hudson JI. Placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in the treatment of binge eating disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1004–1006. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McElroy SL, Arnold LM, Shapira NA, Keck PE, Rosenthal NR, Karim MR, Kanin M, Hudson JI. Topiramate in the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psych. 2003;160:255–261. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fairburn CG. Overcoming binge eating. New York: Guilford Press; [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter JC, Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavioral self-help for binge eating disorder: a controlled effectiveness study. Journ Consul Clin Psychol. 1998;66:616–623. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grilo CM, Masheb RM. A randomized controlled comparison of guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1509–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loeb KL, Wilson GT, Gilbert JS, Labouvie E. Guided and unguided self-help for binge eating. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:259–272. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Engbloom S, Nugent S, Mussell MP, Crow SJ, Thuras P. Self-help versus therapist-led group cognitive-behavioral treatment of binge eating disorder at follow-up. Int J Eat Dis. 2001;30:363–374. doi: 10.1002/eat.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Engbloom S, Nugent S, Mussell MP, Miller JP. Group cognitive-behavioral treatment of binge eating disorder: a comparison of therapist-led vs. self-help formats. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;24:125–136. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199809)24:2<125::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment. 12th. New York: Guilford Press; pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. Three Factor Eating Questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition, and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29:71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rush AJ, Giles DE, Schlesser MA, Fulton CL, Weissenburger J, Burns C. The Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): preliminary findings. Psychiatry Res. 1986;18:65–87. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Kosloski KD, Williams GR. Development of a brief measure to assess quality of life in obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9:102–111. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell JE, Devlin MJ, de Zwaan M, Crow SJ, Peterson CB. Binge-eating disorder: Clinical foundations and treatment. New York: Guilford; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell JE, Fletcher L, Hanson K, Mussell MP, Seim H, Al-Banna M, Wilson M, Crosby R. The relative efficacy of fluoxetine and manual-based self-help in the treatment of outpatients with bulimia nervosa. J Clin Psychopharm. 2001;21(3):298–304. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200106000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Second. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sysko R, Walsh BT. A critical evaluation of the efficacy of self-help interventions for the treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:97–112. doi: 10.1002/eat.20475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lorig K, Ritter PL, Plant K. A disease-specific self-hlp program compared with a generalized chronic disease self-help program for arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheumatism. 2005;53:950–957. doi: 10.1002/art.21604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]