Abstract

This article presents the findings of a study exploring two questions: What age is most efficacious to expose Mexican heritage youth to drug abuse prevention interventions, and what dosage of the prevention intervention is needed? These issues are relevant to Mexican heritage youth—many from immigrant families—in particular ways due to the acculturation process and other contextual factors. The study utilized growth curve modeling to investigate the trajectory of recent substance use (alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, inhalants) among Mexican heritage students (N = 1,670) participating in the keepin’ it REAL drug prevention program at different developmental periods: the elementary school (5th grade), middle school (7th grade), or both. The findings provide no evidence that intervening only in elementary school was effective in altering substance use trajectories from 5th to 8th grade, either for licit nor illicit substances. Implementing keepin’ it REAL in middle school alone altered the trajectories of use of all four substances for Mexican heritage youth. A double dose of prevention, in elementary and middle school proved to be equally as effective as intervening in 7th grade only, and only for marijuana and inhalants. The decrease in use of marijuana and inhalants among students in the 7th-grade-only or the 5th- and 7th-grade interventions occurred just after students received the curriculum intervention in 7th grade. These results are interpreted from an ecodevelopmental and culturally specific perspective and recommendations for prevention and future research are discussed.

Keywords: Substance use prevention, Early intervention, Mexican Americans, Preadolescents, Adolescents

Introduction

Although many children are at risk of substance use from an early age, relatively few substance use prevention programs target elementary aged children (Finke et al. 2002). While only a small proportion of elementary students regularly use substances (Andrews et al. 2003), substantial proportions of students initiate use in elementary school. For example, rates of alcohol use double between grades four and six (Donovan 2007). The average age of adolescents’ first use of alcohol and cigarettes is between 11 and 13 years, and the average for the first use of marijuana is between 13 and 14 years (National Institute on Drug Abuse 2003). Youth who experiment with alcohol and cigarettes at a young age are more likely to report future substance use (Kandel et al. 1992). Furthermore, use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana in elementary school is associated with increased risk of use in middle school (Wilson et al. 2002). And youth with early use experience are more resistant to intervention (Ellickson et al. 1993; Murray et al. 1989). Moreover, even if they do not use substances until later, youths may develop early certain substance use expectations and norms that encourage later substance use. Pro-substance use attitudes and norms are more difficult to change once established (Stipek et al. 1999).

One rationale for intervening in elementary school, even when rates of substance use are low, is to prevent not only the onset of substance use behavior but also the onset of risky attitudes and norms. Using a predominately Mexican-heritage sample, this study assessed the effects of the substance use prevention intervention keepin’ it REAL implemented in elementary school (5th grade) as compared to its effects when implemented in middle school (7th grade), the more common context for such programming (Hecht et al. 2008), and to the program’s effects when implemented at both time points.

Variations by Substance in Early Use

The relative benefits of early intervention may be related to variations by substance in the patterns of use onset. As mentioned earlier, substantial proportions of students initiate substance use by the eighth grade. According to the national Monitoring the Future study, lifetime prevalence rates in eighth grade in 2008 were as follows: 38.9% had drunk alcohol, 18% had been drunk, 20.5% had smoked cigarettes, 14.6% had used marijuana, 15.7% had used inhalants, and 11.2% had used other illicit drugs (Johnston et al. 2009). Alcohol use is the most common first-used substance, with lifetime prevalence rates of 9.8% in 4th grade, 16.1% in 5th grade, and 29.4% in 6th grade (Donovan 2007). According to another national study, the prevalence of alcohol use in the past month ranges from 3–5% among 4th through 6th graders (Donovan 2007). Compared to other ethnic groups, Mexican-heritage youth appear at higher risk of early initiation of substance use. About 25% of Mexican American students in 4th through 6th grade report lifetime use of alcohol (Yin et al. 1995) and by 8th grade more than 20% report drinking alcohol heavily or using marijuana in the last year (Delva et al. 2005). For nearly two decades, Latino youth in the U.S., the majority of Mexican background, have reported higher rates of illicit drug use, alcohol intoxication, and binge drinking than African American and non-Hispanic white youth report (Johnston et al. 2009; National Institute on Drug Abuse 2003).

Once substance use has begun, alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana are the most commonly used substances. However, inhalant use is of particular concern among elementary school children. Inhalants are attractive to young children because they are easily obtained; they need not be purchased, and are readily encountered in the home and neighborhood. Unlike other substances, initiation of inhalant use peaks in grades 6 through 9 (Sakai et al. 2006) and use declines with age (Johnston et al. 2006). Thus, early interventions may be more capable than later interventions of addressing inhalant use, given the latter’s unique salience among younger children.

Early Intervention

Research on the effectiveness of early school-based substance use prevention programs (i.e., intervention prior to 6th grade) is sparse, and what exists presents mixed findings. Research shows that some programs implemented with elementary school students are effective in reducing substance use (Beets et al. 2009; Donaldson et al. 1995; Eddy et al. 2000; Johnson et al. 2009; Schinke et al. 2000), while others are not (Bernat et al. 2007; Donaldson et al. 1994; Weiden Consulting 2000). In a review of 30 elementary school substance use prevention programs, Kam and colleagues (2007) found that fewer than half significantly reduced alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana use. This same review found, however, that more, although not all, programs were successful at addressing one or more precursors of substance use, including anti-drug attitudes and norms, intentions to use drugs, and drug refusal skills. The inconsistency in the support for elementary school intervention indicates a need for further research. The programs examined in the aforementioned research were diverse, and their unique components may help explain why some were effective and others were not. One program’s success or failure may not necessarily predict another’s. That some programs have been effective in influencing either or both substance use behavior and attitudes/norms lends support for the possibility that keepin’ it REAL may have been effective for the 5th graders who received it.

The effectiveness of early intervention may depend on whether it is accompanied by later intervention. Much evidence of the effectiveness of school-based middle school interventions exists (Gottfredson and Wilson 2003). However, less is known about how early and late intervention work in tandem to bring about desired prevention effects. If an early intervention is effective, supplemental intervention may help sustain or increase earlier intervention effects. Only a few studies examine the impact of a second intervention after an initial one is completed. For example, some research on LifeSkills Training, a substance use intervention, shows that program effects were dependent on the receipt of sessions in eighth and ninth grades as well as seventh grade (Botvin 2000; Botvin et al. 1990). Note, however, that this study did not address the question of the benefit of intervention in elementary school relative to later intervention. A recent analysis of a family-focused prevention program called SAFEChildren, originally implemented in first grade, found that the second implementation—in fourth grade—led to relative improvement in child aggression and concentration in school (Tolan et al. 2009). This analysis did not address, however, effects on substance use.

There are reasons why early intervention may be effective, whether alone or in tandem with later intervention. The first is that intervention occurs prior to behavior onset. As noted earlier, by middle school, many children already have substance use experience, and prior use predicts future use (Flay and Petraitis 2006). Because adults who initiate drug use at a young age are more likely to be drug dependent than adults who initiate at a later age (Johnston et al. 1998), prevention interventions might be most effective before behavior onset (Brook et al. 2006).

A second reason is developmental. Elementary school is a period of skill building and eagerness to learn (Berkowitz and Begun 2006), when students may be especially amenable to prevention messages and willing to practice the drug resistance skills presented in an intervention. In contrast to their more egocentric, sensation-seeking middle school elders (Greene et al. 1996; Zuckerman 1994), these students may simply be easier to reach. The elementary school years are also a period of calm relative to the middle school years, which are characterized by rapid developmental changes associated with the onset of puberty and school transitions (Berkowitz and Begun 2006). Earlier intervention may afford children the time they need before the higher-risk period of adolescence to learn decision-making, communication, and drug resistance skills and develop the self-efficacy to use them. In addition, since peer influence has not yet surpassed family influence in elementary school, families may be better able to reinforce program effects for their elementary school than middle school children.

There are, however, arguments against elementary school intervention. Although early interventions may successfully address precursors to substance use like drug-related norms and attitudes, these program effects may not last until the time when they could be translated into behavior—until the middle school years when drug offers and opportunities to use become more common (Moon et al. 1999; Rayle et al. 2006). Furthermore, the cognitive development of elementary students may be too primitive for the teaching of certain drug resistance strategies, such as those requiring abstract reasoning and perspective taking (Case 1985; Piaget 2000; Selman 1980). Finally, attempts to address issues of peer influence may not be effective when the children still fall under the primary influence of their families. Thus, it is not clear if an earlier intervention is more desirable (e.g., 5th vs. 7th grade) or whether it can stand alone without a second implementation (e.g., 5th alone vs. 5th and 7th grade).

Intervention with Mexican-Heritage Youths

The present study focuses on Mexican-heritage youths. While a comparison of intervention effects for different ethnic groups is beyond the scope of this study, there are several reasons why Mexican-heritage youths in particular may benefit from early intervention. As members of an ethnic minority group in the United States, these youths, immigrant and native-born, are experiencing acculturation to mainstream American culture. Research consistently shows that acculturation places youths at higher risk for substance use, whether because of the stress associated with navigating two cultures or because of an exposure to risky behaviors and norms supported by American culture (Castro and Nieri 2010). Mexican-heritage youths are especially vulnerable due to their ethnic minority status and their need to transition from a Mexican approach to a mainstream American approach to race and ethnic identity (Thorne 2005). Teachers, for example, may assign racial and ethnic identities to them—such as Hispanic, Latino, or person of color—that are unfamiliar identities to these students and ones with which they would not identify themselves in Mexico (Lewis 2003). In addition, certain life events, such as migration, may precipitate questions about being a foreigner or introduce conflict between parents and children over cultural differences (Chun and Akutsu 2003). In these contexts, substance use may serve several developmental functions, such as helping to define oneself, bond with peers, gain attention from parents and other adults, etc. (Griffin 2010). Thus, intervening at this stage may provide students with the necessary skills and motivation to choose alternatives to substance use when facing acculturative challenges.

The Intervention: keepin’ It REAL

The intervention analyzed in the present study is keepin’ it REAL, a school-based substance use prevention program (Marsiglia and Hecht 2005). Developed using a culturally grounded approach (Marsiglia and Kulis 2009), it addresses salient cultural variables across certain ethnic groups to meet participants’ unique needs and capitalize on their unique cultural assets. In addition to teaching decision-making, risk assessment and communication skills, keepin’ it REAL teaches four drug resistance strategies: Refuse, Explain, Avoid, and Leave (hence the acronym REAL) through ten classroom-based lessons taught by the classroom teachers. The intervention was originally developed for middle schools students, and this intervention has been proven effective in a randomized controlled trial (Hecht et al. 2003), including for Mexican-heritage youths specifically (Kulis et al. 2005). It is a designated model program on the SAMHSA National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices. The keepin’ it REAL model program for middle schools has also been adapted in several ways. This paper examines an adaptation of the intervention for elementary school students. Both the elementary and middle school interventions were developed in two versions: the original “multicultural” version, and an enhanced version that addresses issues of acculturation that are particularly salient for Mexican-heritage children. The original multicultural version combines different sets of norms and values related to multiple ethnic/racial groups. The acculturation enhanced versions, one for elementary school and another for middle school, more directly address issues of ethnic identity and acculturation and the possible contradictions and cultural tensions that may emerge between norms and values of home culture and mainstream culture.

An analysis of short-term effects of the multicultural version of the elementary school intervention found no differences in substance use attitudes or behaviors between elementary school students in the intervention and control conditions (Hecht et al. 2008). However, this analysis neither distinguished between the original multicultural and acculturation-enhanced versions nor did it compare the effects of the elementary school intervention alone, the middle school intervention alone, and the combination of the elementary school and middle school interventions. This previous study of short-term effects of the elementary school intervention informed the current study by raising questions about the longer-term effects and whether they might be influenced by intervention later, in middle school. Such is the focus of the present study. The hypotheses are guided by the ecodevelopmental perspective, which recognizes the importance of the social and cultural contexts in which minority children and youth operate and their overlapping influences on their drug use attitudes and behaviors (Coatsworth et al. 2002).

Hypotheses

We anticipated that our sample of Mexican-heritage youths would benefit from early exposure to substance use prevention. In particular, we hypothesized that children exposed to the keepin’ it REAL intervention in 5th grade would use substances at lower levels than children exposed to the intervention in 7th grade only and children not exposed to the intervention at all. Furthermore, we hypothesized that children who received the intervention in both 5th and 7th grades would initiate substance use at lower rates than children who received the intervention in one grade only.

Method

Study and Intervention Design

Data for the current analysis came from a six-wave longitudinal study assessing the efficacy of the keepin’ it REAL substance use prevention intervention, which was delivered to elementary and middle school students in a randomized controlled trial. Schools were recruited from seven public school districts serving the city of Phoenix, Arizona and parts of the adjoining suburbs. At the start of the randomized trial, 29 elementary or K-8 schools were block randomized to treatment and control conditions, adjusting for the size and ethnic composition of the school’s enrollment. Students from these schools were tracked over 4 years, from the beginning of 5th to the end of 8th grade, including when elementary students made expected transitions to middle schools at 6th or 7th grade, depending on the school district. Students completed baseline questionnaires in Fall 2004 at the beginning of 5th grade (T1), and five post-test surveys: in Spring 2005 (5th grade—T2), Spring 2006 (6th grade—T3), Fall 2006 (7th grade—T4), Spring 2007 (7th grade—T5), and Spring 2008 (8th grade—T6).

The substance use prevention curriculum was delivered in multiple versions and at different developmental periods. One version was the original keepin’ it REAL multicultural version for middle school students. A second, acculturation enhanced version for middle school students, was created by the study team by modifying the multicultural version, adding two lessons at the end that incorporate information about how to recognize and deal with acculturation challenges. These two versions, targeting middle school youth ages 12–14, were each adapted further to produce parallel interventions suitable for elementary school students—specifically, 5th graders. These adaptations focused on simplifying the language, making the presentation of concepts more concrete, and providing age-appropriate examples (see Harthun et al. 2009). The intervention’s 10–12 lesson curriculum, either in the multicultural or acculturation enhanced version, was delivered over 3–4 months in the randomly assigned treatment schools in 5th grade only (between the T1 and T2 surveys), in 7th grade only (between the T4 and T5 surveys), or in both 5th grade and 7th grade. The present study focuses on differences in the timing of the intervention rather than the relative efficacy of the two versions of the intervention. The acculturation enhanced version was developed to test a hypothesis that it might boost the effectiveness of the original intervention, and it retained all the core elements and nearly all of the content of the original intervention. Accordingly, in the current analysis, students in the multicultural and acculturation enhanced versions were combined if they received those interventions in the same grade levels. After presenting main findings, however, we report on additional tests that assessed whether conclusions held after distinguishing in analysis the two versions of the intervention (original multicultural versus acculturation enhanced).

The keepin’ it REAL curriculum was implemented during regularly scheduled class periods by the students’ teachers. The teachers received day-long training from a master trainer on the study’s curriculum development team, and practiced to deliver the intervention following a detailed teacher manual. Observers from the research team rated the teachers when they implemented the curriculum lessons on the quality of instruction (organization, preparation, student participation and enjoyment) and fidelity to the curriculum manual, both of which were rated highly for all teacher-implementers. After the completion of the curriculum intervention, booster programs to reinforce the keepin’ it REAL prevention messages were delivered in the intervention schools in the following school year, in 6th and/or 8th grade, prior to the follow-up surveys in those school years. Most schools—both control and intervention—had existing prevention activities, often mandated by their districts, that were continued during the randomized trial. These included several control schools that implemented substance abuse prevention programs other than keepin’ it REAL, mostly commonly Project Alert, another SAMHSA model program.

Participants and Data Collection

All 5th grade students in the study schools were invited to participate in the research project and provide survey data to evaluate the intervention. Following university and school district policies on the protection of human subjects, active parental consent was obtained for 82% of the eligible students, and students provided assent to participate at each survey wave. The consent forms sent home to parents and the assent forms presented to students were printed in English and Spanish. At each survey wave, university-trained survey proctors administered a 40–60 min, written questionnaire (provided both in English and Spanish) in the students’ classrooms. Students were informed verbally and in writing that the survey was part of a university research project, their participation was voluntary, and their answers were confidential. Survey proctors assisted students with reading difficulties, and the readability level of questionnaires was assessed to ensure it was appropriate to the grade level. Students with parental consent who were absent on the scheduled survey date were asked to complete the survey in class within a 2-week follow-up period. The proportion of students with parental consent who completed surveys declined from 98% at baseline to 91%, 74%, 60%, 55%, and 47% at the ensuing post-tests; in other words, from 1,670 at the first wave to 785 at the last wave. Multiple imputation methods, described below, were employed to adjust for this attrition and other sources of missing data.

The vast majority of the study participants, 84% overall, were of Mexican heritage, and the present analyses were restricted to this subsample of 1,670 students (see Table 1). This decision was based on the ethnic distribution of the participants and the target group for the acculturation enhanced version of the intervention. The Mexican heritage students constituted the majority of enrolled students in all but two of the study schools, they were the only ethnic group large enough to analyze separately, and they were a group clearly targeted by the acculturation enhanced version. Focusing on the large majority of Mexican heritage study participants provides valuable information on a rapidly growing U.S. youth population that is seldom examined separately in intervention research, and helps ensure that models testing for intervention effects are not subject to unexpected variability among ethnic groups. Students were included in the analysis if they completed any of the six survey waves and indicated that they were of Mexican ethnic background (as “Mexican,” “Mexican American,” or “Chicano”), either on an ethnic and racial group checklist or an item specifying the ethnic label that described them “best.”

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for study respondents using multiply imputed data (N = 1,670)

| Mean/(%) | Standard Deviation | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention 5th grade only (No = 0, Yes = 1) | (45.6%) | 0.498 | 0–1 |

| Intervention 7th grade only (No = 0, Yes = 1) | (13.6%) | 0.343 | 0–1 |

| Intervention 5th and 7th grade (No = 0, Yes = 1) | (15.3%) | 0.360 | 0–1 |

| Control School (No = 0, Yes = 1) | (25.5%) | 0.392 | 0–1 |

| Gender (Male = 0, Female = 1) | (50.4%) | 0.500 | 0–1 |

| Age | 10.390 | 0.572 | 9–13 |

| Usual Grades in School | 6.672 | 1.603 | 1–9 |

| Federal School Lunch Status (Low SES) | 1.308 | 0.592 | 1–3 |

| Alcohol Frequencya | |||

| Wave 1a | 0.104 | 0.306 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 2 | 0.132 | 0.326 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 3 | 0.215 | 0.390 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 4 | 0.289 | 0.452 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 5 | 0.325 | 0.465 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 6 | 0.409 | 0.495 | 0–1.95 |

| Cigarettes frequency | |||

| Wave 1 | 0.043 | 0.224 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 2 | 0.049 | 0.218 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 3 | 0.083 | 0.252 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 4 | 0.133 | 0.317 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 5 | 0.141 | 0.320 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 6 | 0.142 | 0.303 | 0–1.95 |

| Marijuana frequency | |||

| Wave 1 | 0.036 | 0.212 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 2 | 0.035 | 0.190 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 3 | 0.113 | 0.310 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 4 | 0.186 | 0.389 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 5 | 0.244 | 0.448 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 6 | 0.296 | 0.472 | 0–1.95 |

| Inhalants frequency | |||

| Wave 1 | 0.064 | 0.256 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 2 | 0.085 | 0.287 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 3 | 0.111 | 0.287 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 4 | 0.158 | 0.345 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 5 | 0.154 | 0.344 | 0–1.95 |

| Wave 6 | 0.150 | 0.318 | 0–1.95 |

Statistics for substance use outcomes are after natural log transformations

The analysis subsample was almost exactly gender balanced, 50.4% female and 49.6% male. At the start of the study, the students were mostly age typical for 5th grade: 96% were either 10 or 11 years of age (Mean = 10.39 years, SE = 0.57, range = 9–13). Most students would be considered from low income families as indicated by their participation in the federal school lunch program: 76% received a free school lunch and another 17% a reduced price lunch.

Measures

At each survey wave, the questionnaires collected socio-demographic data and self-reports of substance use behaviors and attitudes, which were phrased identically across waves. For the current analyses the outcomes are Likert-type measures of recent substance use behaviors. The major independent variables are dummy variables representing the assignment to intervention and control conditions. Demographic variables serve as controls for possible variation in responsiveness to the intervention or differential individual risk of substance use.

The study examined four substance use-related outcomes, using developmentally appropriate questions for this age group (Kandel and Wu 1995). Students reported the number of times in the last 30 days they had “drunk more than a sip of alcohol,” “smoked cigarettes,” “smoked marijuana (pot, weed),” and “sniffed glue, spray cans, paint or other inhalants to get high,” providing responses in seven categories (0, 1–2, 3–5, 6–9, 10–19, 20–39, 40 or more times). To minimize the effects of skewness—the tendency for most students to report low substance use frequency—we transformed the original scoring of the items by calculating the natural log (i.e., the initial range of 1 to 7 became 0 to 1.95).

Assignment to intervention and control conditions was by school at the time of the baseline survey. Block randomization of schools to study conditions was performed on the schools that agreed to participate during the 7th grade phase of the study. When these were middle schools (only grades 6–8, or 7–8) rather than K-8, the elementary schools that were their designated “feeder” schools were also recruited for the study and assigned the same study condition as the middle school received. Schools were randomized to seven conditions, with one control and six intervention conditions that varied according to both the timing (5th grade only, 7th grade only, or 5th and 7th grades) and version (multicultural or acculturation enhanced) of the intervention. In the current analysis, the two versions of the intervention conditions that were identically timed have been combined so that there are four conditions distinguished in analysis: control, intervention in 5th grade only, intervention in 7th grade only, and intervention in both 5th and 7th grades. These are modeled as dummy variables, with the control condition as the reference.

Socio-demographic control variables used in analysis included gender, age, family socioeconomic status, and academic performance. Gender was measured as a dichotomy, coded female (1) versus male (0). Age was measured in whole years, the age attained on the student’s last birthday. Participation in the school’s federal free or reduced price lunch program served as a proxy for low family socioeconomic status: 0 = not participating, 1 = reduced price lunch, and 2 = free lunch. Academic performance was measured as the “usual grades” received in school with ordinally arranged responses from 1 = “Mostly Fs” to 9 = “Mostly As.” In analysis, gender, age, and school lunch participation were measured as reported at the time of the first survey, the start of 5th grade. Usual school grades were measured as the mean for this item from all the survey waves where the student provided this information.

Analyses

The principal aim of the current study was to examine how changes in substance use over time varied across intervention conditions, specifically whether students exposed to the intervention at different grade levels reported changes in substance use that differed significantly from the control group. We estimated a separate model for frequency of recent use of each of the four types of substances: alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana and inhalants. Because we examined repeated measures of substance use across six survey waves, we selected growth curve modeling to represent the developmental trajectory of substance use among the Mexican heritage participants in the randomized trial of keepin’ it REAL. Growth curve models are forms of hierarchical linear models in which multiple measurements are nested within a single individual (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). In addition to measurements within individuals, we also account for clustering of students within schools, and thus our models have three levels. Measurement waves are nested in students, and students are nested in schools. We investigated both linear and quadratic models of the growth in substance use in unconditional models to determine how best to represent the trajectories for each substance. The growth models were estimated with SAS 9.1, and take the following form:

| (1) |

where Ytij is the substance use outcome at time t for student i in school j, π0ij is the initial level of substance use for student i in school j, π1ij is the linear growth in the level of substance use for student i in school j, π2ij is the quadratic growth for student i in school j, and etij are normally distributed errors. atij represents values for time, which increases linearly (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). The equation in (1) is the level 1 model. Three additional equations specify the level 2 models of initial status and growth (both linear and quadratic). In our models, π0ij and π1ij are predicted with dummy indicators for intervention timing, gender, age, free or reduced price lunch status, and usual grades in school:

| (2) |

| (3) |

Our investigation found that a linear specification of growth was adequate for alcohol and marijuana. For cigarettes and inhalants, however, a quadratic specification more accurately modeled the data. We found that none of the variables added significantly to the quadratic prediction of growth, and thus for cigarettes and inhalants, quadratic growth is modeled as follows:

| (4) |

Clustering is addressed with random coefficients for school-level variation in initial use and its growth:

| (5) |

| (6) |

For cigarettes and inhalants, an additional equation specifies the random coefficient for quadratic growth:

| (7) |

The modeling of linear (π1ij) and quadratic (π2ij) growth defined the timing of survey waves to approximate real time passage. Surveys were spaced at six-month intervals except for those in 6th (T3) and 8th grade (T6), which occurred 1 year after the immediately prior surveys. The coding for time in survey waves 1 through 6 was set to 0, 1, 3, 4, 5, 7 to reflect the actual temporal gaps between successive waves.

Progressive attrition decreased the size of the analysis sample across waves from 1,670 respondents in the baseline wave to 783 in the final wave. About one third (34%) of the participants provided data at all six survey waves, 19% at five waves, 11% at four waves, 14% at three waves, 17% at two waves and 5% at only wave one. This attrition was due mainly to student transfers out of study schools, where students could no longer be located to provide data. The study team successfully employed an extensive tracking system to follow students throughout the study schools.

If there were no missing data, the 1,670 respondents across six waves would have yielded 10,020 observations. However, the present study utilized 7,087 observations across waves, before imputation, with a missing data rate of about 29%. This is not unusually high for school-based studies of adolescent substance use (Aneshensel et al. 1989; Josephson and Rosen 1978). Using multivariate regression, we conducted an attrition analysis to examine which student characteristics predicted the number of survey waves where respondents were missing. Attrition was significantly higher among students who were male, older, earning lower school grades, and low frequency users of inhalants at baseline. Attrition was not predicted by the school lunch proxy for socioeconomic status, or by the baseline frequency of alcohol, cigarettes or marijuana use. Thus, some demographic groups appeared more at risk of attrition—males, students atypically older than their grade level peers, and poor academic performers—possibly due to higher likelihood of transferring among schools and experiencing academic or social integration problems in school that would lead to school absences. It was notable that attrition was not significantly higher among the more frequent users of any substance at baseline. The contrary relationship with inhalant use—more attrition among infrequent users or non-users—was unexpected.

Ad hoc and simple methods of dealing with missing data, such as listwise deletion or mean imputation, can produce deflated standard errors and biased hypothesis tests (Little and Rubin 2002). We employ a more appropriate method, multiple imputation (Little and Rubin 2002), which has been used successfully in studies of prevention program efficacy (Graham et al. 2002). The critical assumption is that, conditional on other non-missing attributes, the data are missing at random (MAR). Although this assumption is untestable, it can be strengthened by including relevant predictors in an imputation model. Using the PROC MI procedure in SAS 9.1, we created 10 complete datasets (which exceeds the 3–5 imputations recommended by Schafer (1997)), analyzed them with complete-data methods, and combined the results of these analyses to arrive at a single estimate that properly incorporates the uncertainty in the imputed values.

Results

Growth Curve Models

Before proceeding to the multivariate tests of prevention program efficacy, we first examined unconditional models—without explanatory predictors—to examine the overall trajectories in substance use, and assess how the variability in substance use was partitioned between individuals and schools. These models (results not shown) tested whether temporal changes in substance use were best represented as a straight linear or a curvilinear trend, and whether there was significant variation in initial substance use and growth in use across individuals. Two unconditional models were estimated for each substance. The first one entered the code for the relative timing of the survey wave (0, 1, 3, 4, 5, 7) to assess the linear growth in substance use over time, and the second model entered this predictor plus its quadratic (0, 1, 9, 16, 25, 49) to assess whether changes in use over time were curvilinear. These models showed that, in the aggregate, frequency of use grew linearly over the six survey waves for two substances: alcohol (β = .045, S.E. = .002, p<.001) and marijuana (β = .041, S.E. = .003, p<.001). Use frequency demonstrated a curvilinear pattern—where increases in use leveled off and then began to decline—for both cigarettes (linear β = .028, S.E. = .004, p<.001; curvilinear β = −.0016, S. E. = .0007, p = .021) and inhalants (linear β = .030, S.E. = .005, p<.001; curvilinear β = −.002, S.E. = .0007, p = .003). These models also showed that students differed in their rates of change, which suggested it was appropriate to apply predictor variables to explain these differential growth trajectories in later models.

We calculated how much variation in use was between schools as opposed to students within schools. The percentage of variation between schools in initial use of alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana and inhalants was quite low, from 0.1% to 0.6%, and the percentage of variation between schools in linear growth of use was also low, 2.7% or lower for each of the four substances. This variance partitioning suggested that, although there was variation in initial use and growth between schools, much more variation occurred across students. Thus, our decision in Eqs. 5, 6, and 7 to not model the between school variation with predictor variables in later models is appropriate. We then estimated conditional models that permitted the trajectories to vary by predictors.

Table 2 presents the results of conditional growth curve models, one for each of the four substance use outcomes. These models have the same predictors, and two sets of coefficients associated with each predictor: 1) coefficients predicting initial substance use levels at the pre-test wave, and 2) coefficients predicting growth in substance use frequency across the six survey waves.

Table 2.

Conditional linear growth models of substance use frequency in last 30 days

| Model number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Cigarettes | Marijuana | Inhalants | |||||

| β | S.E. | β | S.E. | β | S.E. | β | S.E. | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||

| Initial use π0ij | ||||||||

| Intercept γ000 | 0.179 | 0.143 | −0.024 | 0.093 | 0.008 | 0.110 | 0.025 | 0.113 |

| Gender (Male = 0, Female = 1) β01 | −0.036* | 0.015 | −0.031** | 0.010 | −0.018**** | 0.011 | −0.007 | 0.012 |

| Age β02 | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.014**** | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.010 |

| Usual Grades in School β03 | −0.013** | 0.005 | −0.009** | 0.003 | −0.009** | 0.004 | −0.005 | 0.004 |

| Federal School Lunch (Low SES) β04 | 0.002 | 0.012 | −0.003 | 0.008 | −0.009 | 0.010 | −0.003 | 0.010 |

| Intervention 5th Grade Only β05 | −0.038**** | 0.022 | −0.021 | 0.013 | −0.016 | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.016 |

| Intervention 7th Grade Only β06 | 0.005 | 0.026 | −0.002 | 0.017 | −0.003 | 0.020 | 0.032 | 0.021 |

| Intervention 5th & 7th Grade β07 | −0.050* | 0.027 | −0.023 | 0.017 | −0.024 | 0.021 | 0.005 | 0.020 |

| Linear Growth π1ij | ||||||||

| Intercept γ010 | −0.007 | 0.044 | 0.049**** | 0.026 | 0.012 | 0.038 | 0.046 | 0.030 |

| Gender (Male = 0, Female = 1) β11 | 0.009* | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.003 | −0.002 | 0.004 | 0.005**** | 0.003 |

| Age β12 | 0.006 | 0.004 | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.004 | −0.001 | 0.003 |

| Usual Grades in School β13 | −0.002 | 0.002 | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.003** | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| Federal School Lunch (Low SES) β14 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.002 |

| Intervention 5th Grade Only β15 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.006 | −0.004 | 0.004 |

| Intervention 7th Grade Only β16 | −0.012**** | 0.007 | −0.012* | 0.005 | −0.017* | 0.008 | −0.017** | 0.005 |

| Intervention 5th & 7th Grade β17 | −0.006 | 0.007 | −0.008 | 0.005 | −0.015**** | 0.009 | −0.017*** | 0.005 |

| Quadratic growth π2ij | ||||||||

| Intercept γ020 | −0.002* | 0.001 | −0.002** | 0.001 | ||||

| Random Effects | ||||||||

| Level 1 | ||||||||

| Temporal Variation etij | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Level 2 | ||||||||

| Initial Status r0ij | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Linear Growth r1ij | 0.002*** | 0.000 | 0.005*** | 0.001 | 0.002*** | 0.000 | 0.011*** | 0.002 |

| Quadratic Growth r2ij | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| Level 3 | ||||||||

| Initial Status u00j | 0.019*** | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003* | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Linear Growth u01j | 0.115*** | 0.003 | 0.001*** | 0.000 | 0.081*** | 0.002 | 0.000* | 0.000 |

| Quadratic Growth u02j | 0.062*** | 0.002 | 0.079*** | 0.002 | ||||

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001,

p<.10, two-tailed tests

N = 1670

Although the study hypotheses are concerned with the growth in substance use over time, the coefficients for initial use describe any significant differences that were present at baseline. In the model for the amount of alcohol used in the last month (model 1 in Table 2), significant predictors of initial use were gender (β01 = −.036, p< = .013) and usual grades in school (β03 = −.013, p = .010). Controlling for other predictors, the interpretation of these coefficients means that, at the initial pre-treatment survey, females scored .036 points less on the logged alcohol frequency scale, and each additional point on the self-reported grades scale was associated with .013 points less on alcohol frequency. Because the keepin’ it REAL curriculum was randomly assigned to schools, there was no reason to expect that the program participants would differ from controls, but results showed that two of the intervention groups (5th grade only, and 5th and 7th grade) reported lower initial frequency of alcohol use than controls. This unexpected initial difference between intervention and control groups was thus controlled statistically in the analysis.

The coefficients for growth indicate how the intervention conditions and control variables predicted increases in substance use over time. In the growth coefficients in model 1, the intercept (γ010) represents the straight linear growth in alcohol use frequency controlling for gender, age, grades, and school lunch status, indicating that use decreased non-significantly over time for students who were not in any of the intervention groups. By comparison, the unconditional model without predictors described earlier showed the overall trajectory grew significantly every 6 months. Of the control variables, only gender was a significant predictor, with the frequency of alcohol use increasing significantly more steeply for females than for males. Only one of the intervention conditions approached a statistically significant difference from controls in growth of alcohol use frequency: The upward trajectory for students receiving the intervention in 7th grade only was less steep than for controls (β16 = −.012, p = .089).

Model 2 shows growth curve estimates for cigarette use, including a quadratic term representing the timing of the survey wave to fit its curvilinear relationship. This model showed that the initial level of cigarette use was higher among males, older students and those with poor grades, but did not vary significantly by school lunch status or intervention condition. The significant coefficients for growth included the linear and quadratic variables representing survey timing, and one intervention condition. Controlling other variables, growth in cigarette use frequency increased on average every 6 months (γ010 = .049, p = .056), but declined as a function of the quadratic for the 6-month intervals (γ020 = −.002, p = .021), suggesting a leveling off and slight decrease at the later survey waves. As was shown with the model for alcohol use, students in the 7th grade only intervention condition reported cigarette use trajectories that rose significantly less steeply than those in the control group (β16 = −.012, p = .025). The other two intervention conditions, however, were statistically indistinguishable from controls.

The growth curves for marijuana use (Model 3) estimated timing linearly. The predictors of initial use were the same as for alcohol use: There was less frequent initial use of marijuana among females and students with good grades. The significant predictors of growth in marijuana use included school grades, with use increasing less steeply for students performing well academically (β13 = −.009, p = .011). Students in two intervention conditions—7th grade only, and in both 5th and 7th grade—also reported less steep growth in marijuana use than did controls (β16 = −.017, p = .043; β17 = −.015, p = .087).

In the model for frequency of inhalants use (Model 4), there were no significant predictors of initial use. The growth curve was modeled in curvilinear fashion, with estimates for the effects of timing that paralleled those for cigarette use: The overall increase in use every 6 months leveled off and then declined in the later survey waves (γ020 = −.002, p = .002). In addition, the two intervention conditions that showed desirable effects for marijuana use—7th grade only, and in both 5th and 7th grade—also reported less steep growth in use of inhalants than did controls (β16 = −.017, p = .002; β17 = −.017, p = .001).

We explored alternative models that distinguished the two intervention versions, multicultural or acculturation enhanced (results not presented in tables). The results showed that the effects of the timing of the intervention presented above held regardless of the version of the intervention. For example, four of the original six intervention conditions demonstrated significantly less growth in inhalant use compared to controls: those in the 7th grade only multicultural version (β = −.022, p = .007), the 7th grade only acculturation enhanced version (β = −.012, p = .012), the 5th and 7th grade multicultural version (β = −.016, p = .042), and those in the 5th and 7th grade acculturation enhanced version (β = −.019, p = .003). The similarity in the size of the effects of these different versions suggested that the effects of timing were strong regardless of version. Neither of the 5th grade only conditions, whether in the multicultural or the acculturation enhanced version, was statistically different than controls.

We also conducted additional tests of significant differences between specific pairs of intervention and control groups at the last wave, recentering time such that the final survey wave represents the intercept in the growth curve model, and varying the reference category in the dummy coding of intervention or control groups. These tests verified that inhalant use did not differ significantly in the 7th grade only treatment group compared to the 5th and 7th grade treatment group, and that cigarette use in the 5th grade only treatment group did not differ from that of the control group. These findings are consistent with the overall conclusion that the 5th grade treatment groups were no different than controls.

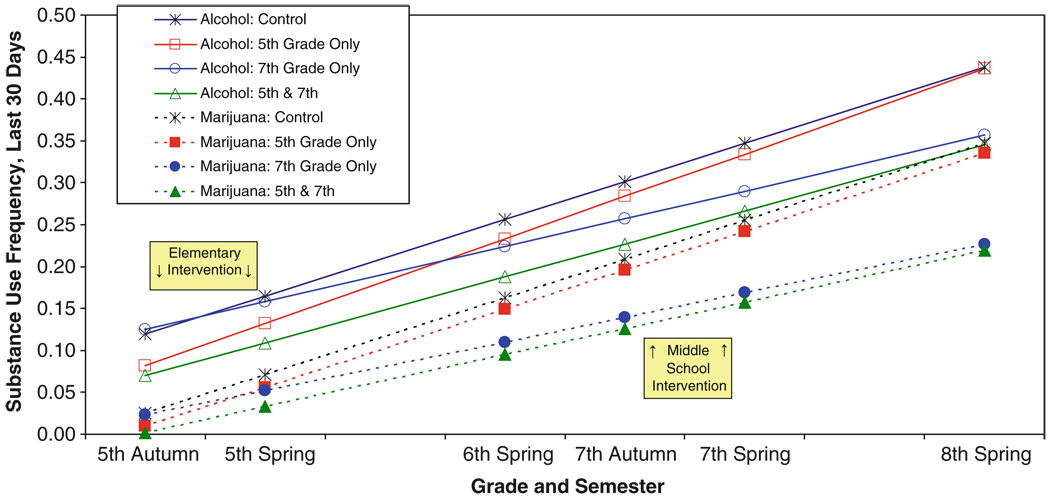

To highlight the effects of intervention timing, Fig. 1 demonstrates the estimated alcohol and marijuana use growth curves for the study conditions, controlling for gender, age, school grades, and school lunch status. For marijuana, all four conditions clustered close to non-use at the beginning of 5th grade, and predicted use grew monotonically thereafter. This growth was steepest in the control schools and those implementing the intervention in 5th grade only, which were virtually indistinguishable. The students in schools implementing the intervention in 7th grade only and in both 5th and 7th grade followed a less steep trajectory of increasing marijuana use.

Fig. 1.

Predicted growth curve trajectories of alcohol and marijuana use, for intervention and control groups

The estimated growth curves for alcohol were different than those for marijuana in notable ways. The 7th grade only intervention group, which was indistinguishable from controls at baseline, was the only intervention group that had a slope appearing less steep than the control group. The other two intervention groups reported less frequent alcohol use than controls at baseline. One group, receiving the 5th and 7th grade intervention, then followed a parallel path to controls, and the other, receiving the 5th grade only intervention, moved upward toward the final aggregate level of alcohol use of the control group.

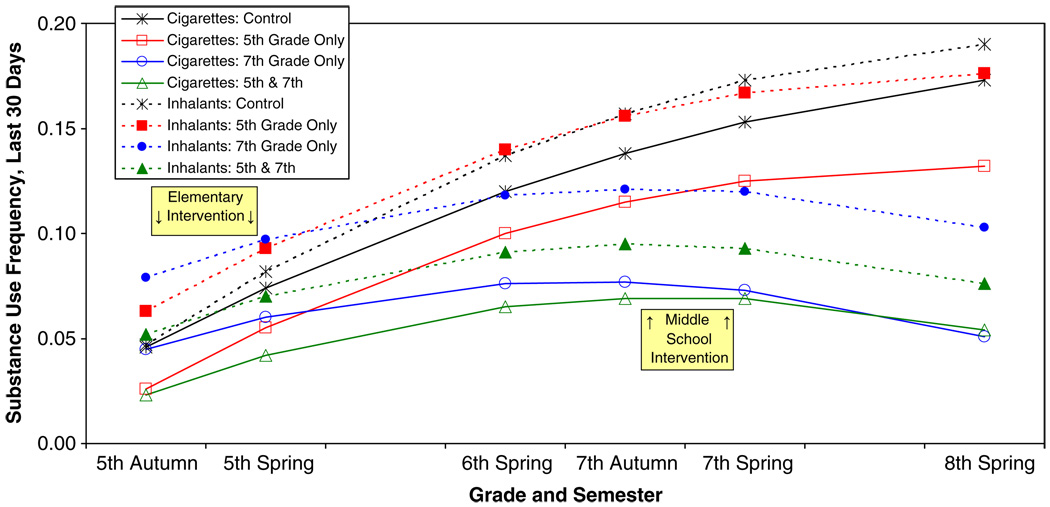

The estimated growth curves for cigarette and inhalants use (Fig. 2) were similar in shape. All study conditions clustered at low levels of use initially, after which the frequency of use climbed through 6th grade and then leveled off. For two conditions—controls and the 5th grade only intervention group—the predicted frequency of cigarette and inhalant use rose at every successive survey, but the rate of increase slowed in 7th and 8th grade. For the other two conditions—students in schools receiving the intervention in 7th grade only and in both 5th and 7th grades—cigarette and inhalants use began to decline between the beginning and the end of 7th grade and continued decreasing to the end of 8th grade.

Fig. 2.

Predicted growth curve trajectories of cigarette and inhalant use, for intervention and control groups

Discussion

We utilized growth curve modeling to investigate the trajectory of substance use among students participating in the keepin’ it REAL drug prevention model program at different developmental periods: elementary school (5th grade), middle school (7th grade), or both. Based on the outcomes examined, Mexican heritage preadolescents did not benefit from receiving the intervention only at an earlier developmental stage (5th grade); they benefited from the earlier intervention solely if it was followed-up by the regular 7th grade intervention. The study was designed to assess whether early intervention in elementary school is more efficacious than the common practice of intervening in middle school, and whether a double dose of prevention—in elementary and middle school—is more effective than a prevention intervention focused on only one developmental period. The findings provided no evidence that intervention in elementary school alone was effective in altering substance use trajectories from 5th to 8th grade; across both licit and illicit substances—alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, and inhalants. In contrast, results showed that implementing the keepin’ it REAL intervention in the middle school years alone altered the trajectories of use of all four substances. These findings confirm earlier findings on the effectiveness of keepin’ it REAL from its original RCT with middle school students (Hecht et al. 2003; Kulis et al. 2005). A double dose of prevention, in elementary and middle school proved to be only about as effective as intervention in 7th grade only, and only for two substances—marijuana and inhalants.

Estimated intervention effects for cigarettes and inhalants from growth curve models suggested that the program accelerated a leveling trend, and actually promoted decreased use, rather than slowing the rate of acceleration in the frequency of use of these two substances. In the case of inhalants, this leveling and slight decline in the trajectory for frequency of use conforms to prior research showing that inhalant use peaks and then declines at early developmental stages (Johnston et al. 2006; Sakai et al. 2006). The timing of the downturn in the growth curve trajectories for cigarettes and inhalants is notable: The decreases in use of these substances among students in the 7th grade only or the 5th and 7th grade interventions occurred just after students received the curriculum intervention in 7th grade.

The absence of 5th-grade only intervention effects on substance use is consistent with a more narrow prior analysis of keepin’ it REAL (Hecht et al. 2008) and with some prior research on other programs (Bernat et al. 2007; Donaldson et al. 1994; Weiden Consulting 2000). However, the implications of this finding are less clear. The early intervention’s inability to affect substance use behaviors might be attributable to a lack of effects on related attitudes, norms, and drug resistance skills (Hecht et al. 2008). Alternately, younger children may not be ready developmentally for the material in the intervention. They may lack experiential knowledge about drug use, and/or have few opportunities to use the knowledge and skills acquired. An analysis of the frequency and types of drug offers and of the changing level of access to substances over time could help address these issues.

Another issue in interpreting the results is the degree of success in adapting the intervention for younger children, both in terms of appropriate curriculum content and format. Although the original middle school intervention was adapted and extensively pilot tested with the active participation of younger students and their teachers, less applicable elements of the cognitive structure of the original version may have been retained despite the developmental adaptation. For example, the curriculum videos illustrating the drug resistance strategies may have felt developmentally atypical to younger students.

Future studies might explore the possibility that only specific subgroups benefitted from the 5th-grade only intervention. Effects on these groups, particularly if they were modest, could have been suppressed in the present analysis that did not distinguish students’ risk levels. Higher risk youths—i.e., those with early substance use experience—may have been the only group to find the prevention material salient or to have opportunities to act on their new knowledge and skills, and thus to show appreciable response to the intervention in the form of attenuated growth in use after initiation. An analysis of the middle school version of keepin’ it REAL found that it promoted reduced and discontinued use among prior substance users (Kulis et al. 2007), in addition to preventing use among non-users. It is an important question if the results we report here for overall use levels among elementary students would be similar to an analysis designed to study substance use initiation, reduction or discontinuation.

While the results lend further evidence that keepin’ it REAL is effective for Mexican-heritage youths in middle school (Kulis et al. 2005), they do not support the notion that this group benefits from early implementation of this intervention. We also found little evidence to support the idea that early intervention was especially advantageous for preventing the use of substances like inhalants that are initiated relatively early. While the combination 5th and 7th grade intervention had desirable effects on inhalant use, the effects were comparable to those of the 7th grade only intervention, suggesting that the latter would be sufficient to prevent use from 7th grade on and that something other than the present 5th grade intervention would be needed to prevent earlier use of this substance. Regarding the latter, some research has shown that relative to the use of other substances, inhalant use is more weakly associated with peer influence (Collins et al. 2008). Since keepin’ it REAL focuses heavily on negotiating peer interactions (Gosin et al. 2003), its lessons may be less applicable to inhalant use, particularly in elementary school when peer influence is only beginning to emerge. Furthermore, this same research shows that parental factors, such as parental disapproval of use and discussion of risks associated with use, play a key role in inhalant use. Early interventions that do not involve parents directly may not influence these factors and thus have less impact on early inhalant use.

The findings of this study advance much needed knowledge about when, how, and with whom to intervene in order to produce the highest possible prevention impact. It confirms previous research suggesting that early interventions are effective when they are followed up by later interventions (Botvin 2000; Gottfredson and Wilson 2003). The findings, however, do not support developmental arguments favoring early intervention during childhood (Berkowitz and Begun 2006). Instead, the findings are in line with cognitive theories that contend that young children are at a concrete stage of cognitive development that makes it difficult for them to understand and integrate certain information (Piaget 2000). Based on the study findings, this limitation may apply to the effectiveness of exposing children to skill-based drug abuse prevention interventions. At this stage of development children may benefit more from general social and academic skills training, rather than focused drug resistance skills.

For Mexican heritage children in this study, starting early did not produce the desired intervention outcomes. In this case, waiting until preadolescence to intervene would be the more cost-effective approach. From an ecodevelopmental perspective (Coatsworth et al. 2002) the findings suggest that Mexican heritage children are somehow protected from the risks present in the larger environment by their families and ethnic communities. These sociocultural protections seem to erode over time and school-based prevention interventions seem to be most needed as these children enter their teen years. Developmental and cultural factors seem to intersect here, suggesting the need to adapt interventions to ethnic groups while targeting age-specific mediators. The study’s findings reveal a need for more theory development to understand better how ethnic culture and cognitive development intersect in ways that have implications for the design of prevention interventions.

Limitations of the Study

One of the main limitations of the study is its regional and localized scope. Despite successful efforts to recruit multiple public school districts and schools within a defined area, the findings are based on a convenience sample of Mexican heritage youth attending public schools in one metropolitan area. Although Mexican heritage children comprise a very large group in this metro area and in the US southwest generally, there are large Mexican and Mexican American communities throughout the country where the intervention program may have different effects. Future research designs should include at least a comparison site in the East and South. Until such research is conducted, any generalizations to other communities in the country need to be made with much caution.

Although random assignment of schools to treatment conditions and multiple imputation of missing data minimized many potential sources of bias in the study, practical constraints in field-based randomized controlled trials imposed limitations. These include increased uncertainty in the parameter estimates due to substantial attrition of participating students due to transfers to non-study schools, failure to track some students successfully from elementary to middle school, and transfers of some students among study schools in different conditions. Because most schools, both experimental and control sites, continued to offer their pre-existing prevention activities, the impact of the keepin’ it REAL intervention may not have been fully isolated from competing prevention messages. Although each of these limitations might have introduced biases of unknown magnitude, the direction of any bias would, in general, be expected to dilute rather than artificially magnify any effects attributable to the intervention.

Implications

The findings of the study have important implications for researchers, prevention designers, and policy makers. Researchers can integrate some of these results as they investigate the processes of onset of drug use across and within ethnic groups and the ideal times to intervene. The study provided clear evidence that early intervention in elementary school alone did not lead to desired effects on substance use trajectories, and that a double dose of intervention in elementary and middle school was no more effective than middle school intervention alone. The largely consistent evidence of the effectiveness of the original keepin’ it REAL intervention for middle school suggests that universal prevention interventions that incorporate specific drug resistance training in culturally appropriate ways continue to demonstrate great promise in preventing and reducing youth substance use.

Acknowledgements

Data analysis was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (P20MD002316-02, F. F. Marsiglia, P.I.). The data were collected with support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R-24 DA 13937-01 and R01 DA005629-09A2). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Flavio F. Marsiglia, Email: marsiglia@asu.edu, School of Social Work, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ, USA; Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, Arizona State University, Mail Code 4320, 411 N. Central Avenue, Suite 720, Phoenix, AZ 85004-0693, USA.

Stephen Kulis, Sociology Program, School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ, USA.

Scott T. Yabiku, Sociology Program, School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Tanya A. Nieri, Sociology Department, University of California, Riverside, CA, USA

Elizabeth Coleman, School of Social Work, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ, USA.

References

- Aneshensel CS, Becerra RM, Fielder EP, Schuler R. Participation of Mexican American female adolescents in a longitudinal panel survey. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1989;53:548–562. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Tildesley E, Hops H, Duncan SC, Severson HH. Elementary school age children’s future intentions and use of substances. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:556–567. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beets MW, Flay BR, Vuchinich S, Snyder FJ, Acock A, Li KK, et al. Use of a social and character development program to prevent substance use, violent behaviors, and sexual activity among elementary-school students in Hawaii. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:1438–1445. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.142919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz M, Begun AL. Designing prevention programs: The developmental perspective. In: Sloboda Z, Bukoski WJ, editors. Handbook of drug abuse prevention. New York: Springer; 2006. pp. 327–348. [Google Scholar]

- Bernat DH, August GJ, Hektner JM, Bloomquist ML. The Early Risers preventive intervention: Testing for six-year outcomes and meditational processes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:605–617. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ. Preventing drug abuse in schools: Social and competence enhancement approaches targeting individual-level etiologic factors. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:887–897. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Baker C, Filazzola AD, Botvin EN. A cognitive behavioral approach to substance abuse prevention: One year follow-up. Addictive Behaviors. 1990;15:47–63. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90006-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, Richter L, Whiteman M. Risk and protective factors of adolescent drug use: Implications for prevention programs. In: Sloboda Z, Bukoski WJ, editors. Handbook of drug abuse prevention. New York: Springer; 2006. pp. 265–287. [Google Scholar]

- Case R. Intellectual development: Birth to adulthood. New York: Academic; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Nieri T. Cultural factors in drug use etiology: Concepts, methods, and recent findings. In: Scheier L, editor. Handbook of drug use etiology: Theory, methods, and empirical findings. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 305–324. [Google Scholar]

- Chun KM, Akutsu PD. Acculturation among ethnic minority families. In: Chun KM, Balls Organista P, Marín G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. Familias Unidas: A family-centered ecodevelopmental intervention to reduce risk for problem behavior among Hispanic adolescents. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2002;5:113–132. doi: 10.1023/a:1015420503275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins D, Pan Z, Johnson K, Courser M, Shamblen S. Individual and contextual predictors of inhalant use among 8th graders: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Drug Education. 2008;38:193–210. doi: 10.2190/DE.38.3.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delva J, Wallace JM, O’Malley P, Bachman JG, Johnston LD, Schulenberg J. The epidemiology of alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine use among Mexican American, Puerto Rican, Cuban American, and other Latin American eighth-grade students in the United States: 1991–2002. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:696–702. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.037051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson SI, Graham JW, Hansen WB. Testing the generalizability of intervening mechanism theories: Understanding the effects of adolescent drug use prevention interventions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;17:195–216. doi: 10.1007/BF01858105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson SI, Graham JW, Piccinin AM, Hansen WB. Resistance-skills training and onset of alcohol use: Evidence for beneficial and potentially harmful effects in public schools and in private Catholic schools. Health Psychology. 1995;14:291–300. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE. Really underage drinkers: The epidemiology of children’s alcohol use in the United States. Prevention Science. 2007;8:192–205. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0072-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy MJ, Reid JB, Fetrow RA. An elementary school-based prevention program targeting modifiable antecedents of youth delinquency and violence: Linking the interests of families and teachers (LIFT) Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2000;8:166–176. [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Bell RM, McGuigan K. Preventing adolescent drug use: Long-term results of a junior high program. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83:856–861. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finke L, Williams J, Ritter M, Kemper D, Kersey S, Nightenhauser J, et al. Survival against drugs: Education for school-aged children. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2002;15:163–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2002.tb00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Petraitis J. Bridging the gap between substance use prevention theory and practice. In: Sloboda Z, Bukoski WJ, editors. Handbook of drug abuse prevention. New York: Springer; 2006. pp. 289–306. [Google Scholar]

- Gosin M, Marsiglia FF, Hecht ML. keepin' it REAL: A drug resistance curriculum tailored to the strengths and needs of preadolescents of the Southwest. Journal of Drug Education. 2003;33:119–142. doi: 10.2190/DXB9-1V2P-C27J-V69V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, Wilson DB. Characteristics of effective school-based substance abuse prevention. Prevention Science. 2003;4:27–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1021782710278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Roberts MM, Tatterson JW, Johnston SE. Data quality in evaluation of an alcohol-related harm prevention program. Evaluation Review. 2002;26:147–189. doi: 10.1177/0193841X02026002002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene K, Rubin DL, Walters LH, Hale JL. The utility of understanding egocentrism in designing health promotion messages. Health Communication. 1996;8:131–152. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW. The epidemiology of substance use among adolescents and young adults: A developmental perspective. In: Scheier L, editor. Handbook of drug use etiology: Theory, methods, and empirical findings. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Harthun ML, Dustman PA, Reeves LJ, Marsiglia FF, Hecht ML. Using community-based participatory research to adapt keepin’ it REAL: Creating a socially, developmental, and academically appropriate prevention curriculum for 5th graders. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2009;53:12–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Elek E, Wagstaff DA, Kam JA, Marsiglia F, Dustman P, et al. Immediate and short-term effects of the 5th grade version of the keepin' it REAL substance use prevention intervention. Journal of Drug Education. 2008;38:225–251. doi: 10.2190/DE.38.3.c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Marsiglia FF, Elek E, Wagstaff DA, Kulis S, Dustman P. Culturally grounded substance use prevention: An evaluation of the keepin’ it REAL curriculum. Prevention Science. 2003;4:233–248. doi: 10.1023/a:1026016131401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KW, Shamblen SR, Ogilvie KA, Collins D, Saylor B. Preventing youths’ use of inhalants and other harmful legal products in frontier Alaskan communities: A randomized trial. Prevention Science. 2009;10:298–312. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0132-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future: National results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2006 (NIH Publication No. 07-6202)

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2008. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2009 (NIH Publication No. 09-7401)

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG. National survey results on drug use from the Monitoring the Future study, 1975–1997. Volume II: College students and young adults. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1998 NIH Publication No. 98-4346.

- Josephson E, Rosen MA. Panel loss in a high school drug study. In: Kandel D, editor. Longitudinal research on drug use: Empirical findings and methodological issues. Washington, DC: Hemisphere; 1978. pp. 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kam JA, Elek E, Hecht ML. Reviewing the effectiveness of elementary school-based substance use prevention programs. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Prevention Research; Washington, DC. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Wu P. The contribution of mothers and fathers to the intergenerational transmission of cigarette smoking in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1995;5:225–252. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Yamaguchi K, Chen K. Stages of progression in drug involvement from adolescence to adulthood: Further evidence for the gateway theory. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1992;53:447–457. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Marsiglia FF, Elek E, Dustman P, Wagstaff DA, Hecht ML. Mexican/Mexican American adolescents and keepin’ it REAL: An evidence-based substance use prevention program. Children & Schools. 2005;27:133–145. doi: 10.1093/cs/27.3.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Nieri T, Yabiku S, Stromwall L, Marsiglia FF. Promoting reduced and discontinued substance use among adolescent substance users: Effectiveness of a universal prevention program. Prevention Science. 2007;8:35–49. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0052-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A. Race in the schoolyard: Negotiating the color line in classrooms and communities. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wileya; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Hecht ML. Keepin’it REAL: An evidence-based program. Santa Cruz, CA: ETR; 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S. Diversity, oppression and change: Culturally grounded social work. Chicago, IL: Lyceum; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Moon DG, Hecht ML, Jackson KM, Spellers RE. Ethnic and gender differences and similarities in adolescent drug use and refusals of drug offers. Substance Use & Misuse. 1999;34:1059–1083. doi: 10.3109/10826089909039397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray DM, Pirie P, Leupker RV, Pallonen U. Five- and six-year follow-up results from four seventh-grade smoking prevention strategies. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1989;12:207–218. doi: 10.1007/BF00846551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug use among racial/ethnic minorities. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health; 2003 (NIH Publication No. 03-3888)

- Piaget J. Piaget’s theory. In: Lee K, editor. Childhood cognitive development: The essential readings. Essential readings in developmental psychology. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2000. pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchial linear models. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rayle AD, Kulis S, Okamoto SK, Tann SS, LeCroy CW, Dustman P, et al. Who is offering and how often? Gender differences in drug offers among American Indian adolescents of the Southwest. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2006;26:296–317. doi: 10.1177/0272431606288551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai JT, Hall SK, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Crowley TJ. Adolescent inhalant use among male patients in treatment for substance and behavior problems: Two-year outcome. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:29–40. doi: 10.1080/00952990500328513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schinke SP, Tepavac L, Cole KC. Preventing substance use among Native American youth: Three-year results. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:387–397. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selman R. The growth of interpersonal understanding: Developmental and clinical analyses. New York: Academic; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Stipek D, de la Sota A, Weishaupt L. Life lessons: An embedded classroom approach to preventing high-risk behaviors among preadolescents. The Elementary School Journal. 1999;99:433–451. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne B. Unpacking school lunchtime: Structure, practice, and the negotiation of differences. In: Cooper CR, Coll CTG, Bartko WT, Davis H, Chatman C, editors. Developmental pathways through middle childhood: Rethinking context and diversity as resources. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. pp. 63–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Henry D, Schoeny M. The benefits of booster interventions: Evidence from a family-focused prevention program. Prevention Science. 2009;10:287–297. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiden Consulting. Science, tobacco, & you outcome evaluation: Phase 2 report. 2000 Downloaded on 1/5/10 from http://scienceu.fsu.edu/evaluations/index.html.

- Wilson N, Battistich V, Syme SL, Boyce WT. Does elementary school alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use increase middle school risk? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:442–447. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00416-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z, Zapata JT, Katims DS. Risk factors for substance use among Mexican American school-age youth. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]