Abstract

REV-ERBα is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily that functions as a receptor for the porphoryin heme. REV-ERBα suppresses transcription of its target genes in a heme-dependent manner. Recently, the first non-porphyrin synthetic ligand for REV-ERBα GSK4112, was designed and it mimics the action of heme acting as agonist. Here, we report the identification of the first REV-ERB antagonist, SR8278. SR8278 is structurally similar to the agonist, but blocks the ability of the GSK4112 enhance REV-ERBα-dependent repression in a cotransfection assay. Additionally, whereas GSK4112 suppresses the expression of REV-ERBα target genes involved in gluconeogenesis, SR8278 stimulates the expression of these genes. Thus, SR8278 represents a unique chemical tool for probing REV-ERB function and may serve as a point for initiation of further optimization to develop REV-ERB antagonists with the ability to explore circadian and metabolic functions.

REV-ERBα and REV-ERBβ are unusual members of the nuclear receptor (NR) superfamily that displays ligand-dependent transcriptional repression activity. We and others identified the porphyrin heme as the physiological ligand for this receptors (1, 2). Heme binding is required for these receptors to recruit corepressors such as NCoR so that it may actively repress transcription of its target genes. Although considerably more is known about the function of REV-ERBα then REV-ERBβ it is assumed that they play similar physiological roles based on their conserved patterns of expression and recognition of identical DNA binding sites. REV-ERBα plays a critical role in regulation of the circadian rhythm where it directly modulates the expression of Bmal1 expression (3, 4). Additionally, REV-ERBα has been shown to regulate metabolic processes including lipid and glucose metabolism (2, 5–7).

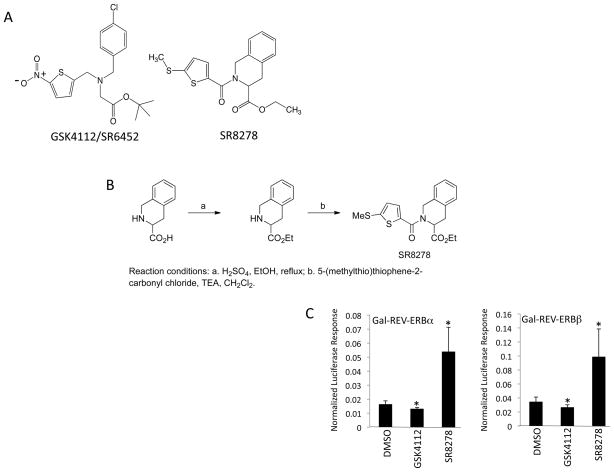

Soon after characterization of REV-ERB as a ligand-dependent NR the first synthetic ligand was identified (8). This ligand acted as an agonist, mimicking the action of heme, in cell-based assays and also was able to reset the circadian rhythm in a phasic manner (8). Our lab examined this compound, GSK4112/SR6452 (Fig. 1A), and found that it induced adipogenesis in a manner similar treatment with heme or overexpression of REV-ERBα in 3T3-L1 cells (9).

Figure 1.

Identification of a REV-ERBα antagonist. A) Structure of GSK4112 compared to SR8278. B) Schematic illustrating the synthesis of SR8278. C) GAL4-REV-ERB cotransfection assay illustrating the activity of GSK4112 and SR8278. 10 μM drug was used. An internal Renilla luciferase control is included to normalize the data for all cotransfection assays. The action of REV-ERB is to suppress transcription so ligands that induce this effect are called agonists and ligands that block this effect are termed antagonists. Since heme is the natural agonist and is ubiquitous these data are consistent with the antagonists blocking the endogenous activity of heme. REV-ERB that is incapable of binding heme is inactive and unable to suppress transcription. *, p<0.05 via students t test.

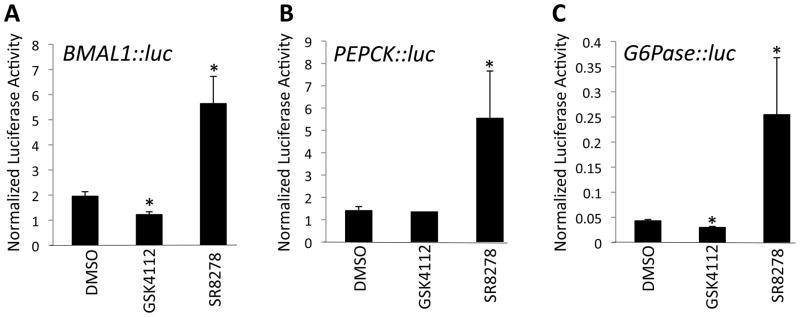

Upon further analysis of compounds within the GSK4112 tertiary amine scaffold we identified one compound, SR8278 (Fig. 1A and 1B), that displayed REV-ERBα antagonist activity in contrast to the agonist activity displayed by GSK4112. The activity of SR8278 was first assessed in a cotransfection assay in HEK293 cells where chimeric receptors composed of the DNA-binding domain of GAL4 fused to either REV-ERBα or REV-ERBβ were transfected in the cells along with a luciferase reporter containing GAL4 binding sites in the promoter. We previously used this assay system to demonstrate that the repressive effects of REV-ERBα were heme-dependent since elimination of the heme binding activity of the receptor eliminated the ability of the receptor to repress transcription of the reporter gene (10). We took advantage of this cell-based system where heme, a REV-ERB agonist, is always present and mediating repressor activity of the receptor to assess the activity of the antagonist, SR8278. As shown in Fig. 1C, addition of GSK4112 to either the REV-ERBα or REV-ERBβ assay results in enhanced repression. Addition of SR8278 shows the opposite effect enhancing the expression of the reporter gene presumably due to blocking the action of the endogenous agonist heme. We performed a similar assay in where we transfected the cells with full-length REV-ERBα and a luciferase reporter driven by the three different promoters all derived from REV-ERBβ target genes. The Bmal1, glucose 6-phosphatase (G6Pase), and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) promoters fused to luciferase were used. As shown in Fig. 2, we treated the cells with either GSK4112 or SR8278 and observed a pattern very similar to that observed when we performed the GAL4 chimeric receptor assay. Generally, GSK4112 suppressed reporter gene expression and SR8278 enhanced expression.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the cell-based activity of a REV-ERB agonist and antagonists. HEK293 cells were transfected with REV-ERBα and a luciferase reporter under the control of the promoter of a REV-ERB target genes, Bmal1 (A), PEPCK (B) or G6Pase (C). Cells were then treated with 10 μM compound for 24h followed by the luciferase assay. *, p<0.05 via students t test.

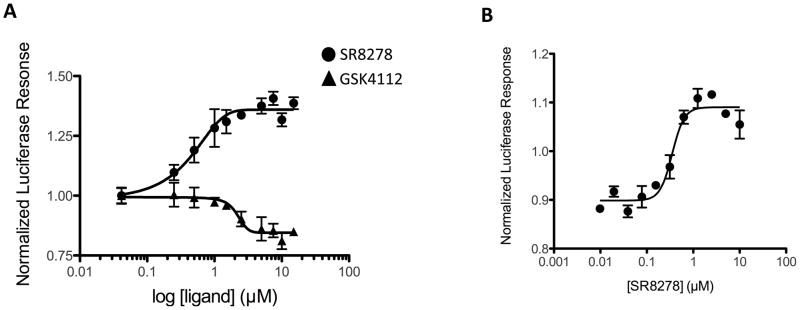

We utilized the Bmal1 reporter to examine the activity of SR8278 more closely. GSK4112 dose-dependently suppressed transcription driven by the Bmal1 promoter (IC50=2.3μM) (Fig. 3A). It should be noted that activity displayed by GSK4112 is in addition to the heme-dependent activity that is associated with REV-ERBα as is the case with all the cell-based assays. It is clear that a mutant REV-ERBα that is devoid of heme binding activity is transcriptionally inactive and unable to modulate transcription due to inability to recruit NCoR (1, 2). Addition of the antagonist, SR8278, results in inhibition of the REV-ERBα transcriptional repression activity in a dose-dependent manner (EC50=0.47μM) (Fig. 2). SR8278 displays potency nearly 5 times greater than GSK4112 in this assay. We also assessed the ability of SR8278 to block the action of GSK4112 in the cotransfection assay. Cells were treated with 5 μM GSK4112 resulting in suppression of transcription as shown in Fig. 3B. Increasing doses of SR8278 eliminated the activity of GSK4112 and as illustrated in Fig. 3, activity increased above baseline due to the effect of SR8278 also blocking the action of heme. The potency of SR8278 in this assay was 0.35 μM.

Figure 3.

SR8278 functions as a REV-ERB antagonist. A) Comparison of the cell-based activity of a REV-ERB agonist and antagonist. BMAL1-luciferase/REV-ERBa cotransfection assay was performed as in figure 2 and cells were then treated with various doses of compounds for 24h followed by the luciferase assay. B) BMAL1-luciferase/REV-ERBα cotransfection assay was performed as in figure 2 in the presence of the agonist, SR6452 (5 μM) and increasing amounts of the antagonist SR8278 was added. SR6452 decreased transcription (agonist activity) and increasing amounts of SR8278 blocked this activity dose-dependently (IC50=0.35 μM). This assay is a cell-based assays and there are physiological levels of heme present. This likely results in the ability of SR8278 to bring the activity above baseline - the compound is antagonizing heme activity.

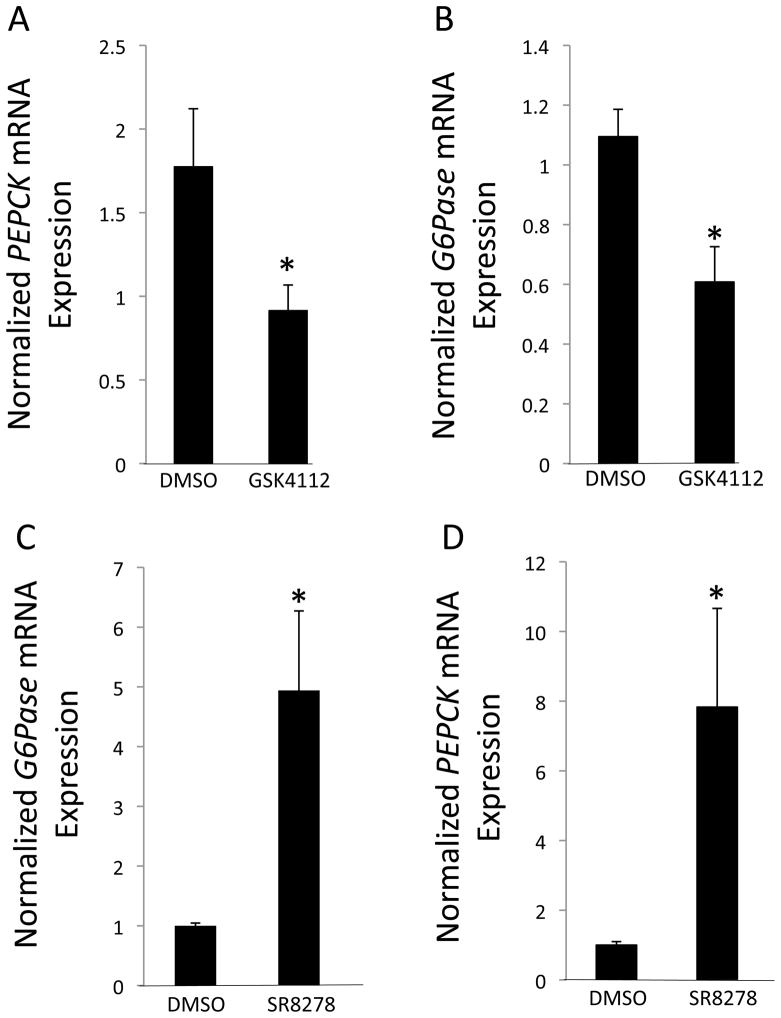

In order to further characterize the activity of SR8278, we assessed the ability of this compound to modulate the expression of target gene expression in cells that express REV-ERBα endogenously. REV-ERBα regulates glucose production in hepatocytes via modulation of the expression of key genes such as G6Pase and PEPCK (2). REV-ERBα suppresses the expression of these genes in a heme-dependent manner and the synthetic REV-ERBα ligand, GSK4112, also suppresses the expression of these genes (Fig. 4A & 4B) (2, 11). In HepG2 cells, endogenous levels of heme acting on REV-ERBα maintain a tonic suppression of these genes (2), thus we expected that addition of SR8278 would result in an increase in expression of these genes due to blocking the action of the endogenous agonist. As shown in Fig. 4C & 4D this is exactly what we observed. Treatment of HepG2 cells with SR8278 resulted in a significant increase in the expression of either G6Pase or PEPCK mRNA expression.

Figure 4.

Modulation of the expression of REV-ERBα target genes, G6Pase and PEPCK, by a REV-ERBα agonist, GSK4112, and antagonist, SR8278. HepG2 cells were treated with 10 μM drug or vehicle (DMSO) for 24 h prior to harvesting the cells for mRNA. A) Suppression of PEPCK mRNA expression by GSK4112. B) Suppression of G6Pase mRNA expression by GSK4112. C) Stimulation of PEPCK mRNA expression by SR8278. D) Stimualtion of G6Pase mRNA expression by SR8278. Note that the endogenous REV-ERBα agonist, heme, is present in cells thus there is basal suppression of REV-ERBα target genes. Addition of a REV-ERBα antagonist would be expected to block this leading to apparent stimulation of gene expression due to blocking heme action. Gene expression was normalized to cyclophilin mRNA. *, indicates p<0.05 via students t test.

In summary, we report the identification of the first REV-ERBα antagonist in this study. Treatment of HepG2 cells with SR8278 results in increased expression of REV-ERBα target genes consistent with the compound blocking the action of the endogenous agonist, heme. In a cell-based assay, SR8278 is considerably more potent than the other synthetic REV-ERBα ligand, GSK4112, which functions as an agonist. Like GSK4112 (11), SR8278 displayed poor pharmacokinetic properties that will likely limit its use to biochemical and cell-based assays (data not shown). Nevertheless, SR8278 represents a novel chemical tool that can be used to probe the function of REV-ERBα in cell-based models and may be used as a point to initiate optimization of more potent and efficacy REV-ERBα antagonists as well as in vivo probes.

Methods

Synthesis of SR8278

To a mixture of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (2 g) in anhydrous ethanol (50 ml) was added H2SO4 (1 ml). The resulting solution was refluxed for 18h, cooled to room temperature, and then concentrated in vacuo to remove the ethanol. The residue was dissolved in ethyl acetate and saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution, and the layers were separated. The organic layer was washed with sat. aqueous NaHCO3 (2x), brine (2x), and dried (MgSO4) and concentrated to afford ethyl 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxylate as a pale yellow oil, which slowly crystallized. The compound was used without further purification.

To the crude aminoester in methylene chloride (50 ml) at 0°C was added triethylamine (1.5 eq). A solution of 5-(methylthio)thiophene-2-carbonyl chloride (1.2 eq) in methylene chloride was added dropwise and the reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature overnight. After 18 h, the reaction was concentrated to remove the solvent. The crude residue was resuspended in ethyl acetate and washed with 1M HCl (2x), NaHCO3 (2x), brine (1x), dried (MgSO4) and concentrated. The crude product was purified by chromatography on silica gel to afford SR8278 as a near colorless oil >95% pure as judged by reverse-phase analytical HPLC analysis.

Cell Culture and Cotransfections

HEK293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagles medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C under 5% CO2. HepG2 cells were maintained and routinely propagated in minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C under 5% CO2. 24 h prior to transfection, HepG2 cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 15 × 103 cells/well. Transfections were performed using LipofectamineTM 2000 (Invitrogen). Sixteen h post-transfection, the cells were treated with vehicle or compound. 24 h post-treatment, the luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-GloTM luciferase assay system (Promega). The values indicated represent the means ± S.E. from four independently transfected wells. The experiments were repeated at least three times. The REV-ERBα and reporter constructs have been previously described (9,12).

cDNA Synthesis and Quantitative PCR

Total RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis as well as the QPCR were performed as previously described (10,12).

Acknowledgments

This work was also supported by NIH grants DK080201 (T.P.B.). The efforts of TMK were supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Molecular Library Screening Center Network (MLSCN) grant U54MH074404 (Hugh Rosen, Principal Investigator).

References

- 1.Raghuram S, Stayrook KR, Huang P, Rogers PM, Nosie AK, McClure DB, Burris LL, Khorasanizadeh S, Burris TP, Rastinejad F. Identification of heme as the ligand for the orphan nuclear receptors REV-ERB[alpha] and REV-ERB[beta] Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1207–1213. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yin L, Wu N, Curtin JC, Qatanani M, Szwergold NR, Reid RA, Waitt GM, Parks DJ, Pearce KH, Wisely GB, Lazar MA. Rev-erb{alpha}, a Heme Sensor That Coordinates Metabolic and Circadian Pathways. Science. 2007;318:1786–1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1150179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guillaumond F, Dardente H, Giguere V, Cermakian N. Differential control of Bmal1 circadian transcription by REV-ERB and ROR nuclear receptors. Journal of Biological Rhythms. 2005;20:391–403. doi: 10.1177/0748730405277232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preitner N, Damiola F, Molina LL, Zakany J, Duboule D, Albrecht U, Schibler U. The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERB alpha controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell. 2002;110:251–260. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00825-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chawla A, Lazar MA. INDUCTION OF REV-ERBA-ALPHA, AN ORPHAN RECEPTOR ENCODED ON THE OPPOSITE STRAND OF THE ALPHA-THYROID HORMONE-RECEPTOR GENE, DURING ADIPOCYTE DIFFERENTIATION. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:16265–16269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raspe E, Mautino G, Duez H, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Transcriptional regulation of apolipoprotein C-III gene expression by the orphan nuclear receptor Rev-erb alpha. Circulation. 2001;104:15–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004982200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duez H, Van Der Veen JN, Duhem C, Pourcet B, Touvier T, Fontaine C, Derudas B, Bauge E, Havinga R, Bloks VW, Wolters H, Van Der Sluijs FH, Vennstrom B, Kuipers F, Staels B. Regulation of bile acid synthesis by the nuclear receptor Rev-erb alpha. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:689–698. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meng QJ, McMaster A, Beesley S, Lu WQ, Gibbs J, Parks D, Collins J, Farrow S, Donn R, Ray D, Loudon A. Ligand modulation of REV-ERB{alpha} function resets the peripheral circadian clock in a phasic manner. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3629–3635. doi: 10.1242/jcs.035048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar N, Solt LA, Wang Y, Rogers PM, Bhattacharyya G, Kamenecka TM, Stayrook KR, Crumbley C, Floyd ZE, Gimble JM, Griffin PR, Burris TP. Regulation of Adipogenesis by Natural and Synthetic REV-ERB Ligands. Endocrinology. 2010:en.2009–0800. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raghuram S, Stayrook KR, Huang P, Rogers PM, Nosie AK, McClure DB, Burris LL, Khorasanizadeh S, Burris TP, Rastinejad F. Identification of heme as the ligand for the orphan nuclear receptors REV-ERBalpha and REV-ERBbeta. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1207–1213. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant D, Yin L, Collins JL, Parks DJ, Orband-Miller LA, Wisely GB, Joshi S, Lazar MA, Willson TM, Zuercher WJ. GSK4112, a Small Molecule Chemical Probe for the Cell Biology of the Nuclear Heme Receptor Rev-erbα. ACS Chemical Biology. doi: 10.1021/cb100141y. null-null. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar N, Solt LA, Conkright JJ, Wang Y, Istrate MA, Busby SA, Garcia-Ordonez R, Burris TP, Griffin PR. The benzenesulfonamide T0901317 is a novel ROR{alpha}/{gamma} Inverse Agonist. Molecular Pharmacology. 2010;77:228–236. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.060905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]