Abstract

The full benefit of prevention science will not be realized until we learn how to influence organizational practices. The marketing of tobacco, alcohol, and food and corporate advocacy for economic policies that maintain family poverty are examples of practices we must influence. This paper analyzes the evolution of such practices in terms of their selection by economic consequences. A strategy for addressing these critical risk factors should include: (a) systematic research on the impact of corporate practices on each of the most common and costly psychological and behavior problems; (b) empirical analyses of the consequences that select harmful corporate practices; (c) assessment of the impact of policies that could affect problematic corporate practices; and (d) research on advocacy organizations to understand the factors that influence their growth and to help them develop effective strategies for influencing corporate externalities.

Keywords: Prevention, Intervention, Policymakers, Organizational practices, Advocacy

The recent report of the Institute of Medicine documents the tremendous progress that prevention scientists have made (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine 2009). However, further progress will be limited if prevention science does not expand its scope to address the harmful effects of negative corporate externalities.

A negative corporate externality is the harm that the business transaction of a corporation does to a third party (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development 2008). For example, power plants may emit mercury, but not pay for the damage that mercury causes to those who live near the plant. To fulfill its promise for improving human wellbeing, prevention science must document negative externalities, develop strategies for altering them, and then test those strategies (Biglan 2009). In this paper, I review evidence of the harmful impact of practices of the tobacco and alcohol industries as well as certain segments of the food industry. I also examine the harm that a segment of the business community has brought about by advocating for policies that have maintained poverty among a large proportion of Americans. I then provide a framework for understanding the evolution of harmful practices and provide strategies for evolving practices to counter these harmful practices.

The Epidemiology of Corporate Influences on Wellbeing

If prevention science is to fulfill its mission of increasing the wellbeing of every person, it must clarify the way in which some corporate practices are risk factors for psychological, behavioral, and physical ill health. Below are four examples.

Tobacco Industry Practices

The most extensively studied corporate influences on health are the marketing, lobbying, and public relations practices of tobacco companies. In U.S. v. Philip Morris et al., Judge Gladys Kessler ruled, “The evidence is clear and convincing—and beyond any reasonable doubt—that Defendants have marketed to young people twenty-one and under while consistently, publicly, and falsely denying that they do so…Defendants’ marketing activities are intended to bring new, young, and hopefully long-lived smokers into the market in order to replace those who die (largely from tobacco caused illness) or quit” (U.S. v. Philip Morris et al. 2006).

By basing her conclusion on empirical research, Judge Kessler set an important public health precedent. For the first time, research helped to establish empirically that the marketing practices of an industry pose a risk for a disease process. Until the 1990s, most epidemiological research on tobacco use had focused on the intrapersonal, family, and peer influences on tobacco use. However, a number of investigators began to analyze the relationship between young people’s exposure to cigarette advertising and their initiation of smoking.

Summaries of this research are in a recent National Cancer Institute (NCI) monograph (2008) and in my testimony in U.S. vs. Philip Morris et al. (Biglan 2004). Numerous studies found that adolescents who were receptive to cigarette advertising were more likely to smoke (Audrain-McGovern et al. 2003; Chen et al. 2002; Evans et al. 1995; Feighery et al. 1998; Kaufman et al. 2002; Sargent et al. 2000a; Tercyak et al. 2002; Unger and Chen 1999; Unger et al. 2001). Youth prefer ads for youth-popular brands over those for less popular brands (Arnett 2001).

We found 13 longitudinal studies showing that exposure to advertising predicted initiation of smoking (Aitken et al. 1991; Alexander et al. 1983; Armstrong et al. 1990; Biener and Siegel 2000; Charlton and Blair 1989; Choi et al. 2002; Gilpin et al. 2007; Lopez et al. 2004; Pierce et al. 1998, 2002; Pucci and Siegel 1999; Sargent et al. 2000a, b; While et al. 1996). The tobacco companies argued that no experimental evidence showed that exposure to advertising influenced smoking. Obviously, conducting such a study would be unethical, but we found five experimental studies that manipulated youth exposure to cigarette advertising, each finding that exposure to advertising increased well-established precursors of actual smoking, including attitudes toward smokers and smoking (Donovan et al. 2002; Pechmann and Knight 2002; Pechmann and Ratneshwar 1994; Turco 1997) and perceptions of how many youth smoke (Henriksen et al. 2002).

Marketing is not the only aspect of tobacco industry practices that researchers have studied. The voluminous evidence introduced in U.S. v. Philip Morris et al. (2006) was the basis for Judge Kessler’s ruling that the industry had used public relations and lobbying practices to deceive the public about smoking’s harmfulness and the fact that the industry was advertising to youth. Many documents showed that, although the industry introduced a program ostensibly intended to prevent youth smoking, it actually designed the program to prevent legislation restricting tobacco advertising (Biglan 2004).

Alcohol Marketing

Although less developed than research on tobacco marketing, research on the influence of alcohol marketing has begun to implicate it in youth drinking. Agostinelli and Grube (2002) reviewed the evidence: They found that, in 2001, the industry spent $1.42 billion in advertising, $893 million of it on broadcast ads. Advertising expenditures rose 37% from 1995 to 2000; 95% of its TV ads are on sports programs. Due to these practices, most youth are constantly exposed to alcohol advertising. Content analyses of the advertising indicate that the ads link drinking with social acceptance, an important factor in tobacco marketing success (NCI 2008). The Harvard College Drinking Study of 118 colleges (Kuo et al. 2003) reported a substantial amount of special promotions and price marketing around campuses and found that the rates of binge drinking and amount of alcohol consumed on campuses was directly related to the extent of price discounting and promotion in these outlets.

Grube (2004) found only four studies that experimentally evaluated the impact of alcohol advertising on alcohol use or alcohol-related behavior; study results varied. Grube (2004) did note that the studies typically took place in artificial settings, used a limited number of ads that may not have been the most effective with youth, assessed only short-term impact, and may have had limited impact because all subjects were already heavily exposed to alcohol advertising. Thus, we can summarize the most appropriate conclusion with the well-worn cliché, “More research is needed.”

Saffer and Dave (2003) used data on variation in local alcohol advertising expenditures and data from Monitoring the Future and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 to estimate what impact a complete alcohol advertising ban would have on youth consumption. They concluded that such a ban would reduce teen alcohol use in the last month by 24% and would reduce youthful binge drinking by 42%. On the other hand, Nelson (2003) concluded that advertising bans do not reduce total alcohol consumption.

Just recently, the British Medication Association recommended a ban on alcohol marketing (Triggle 2009). The members of the association said their action was critical, since alcohol is now one of the leading causes of early death and disability.

Food Production and Marketing

There has been an alarming increase in obesity in the U.S. over the past two to three decades. Food marketing and production practices are an important risk factor for obesity, cardiovascular disease, depression, and aggressive social behavior. It is prompting increased concern about the production and marketing of food. The American diet has shifted heavily toward corn- and soy-based products. Michael Pollan has documented how high fructose corn syrup now sweetens many beverages. A chicken nugget consists of cornfed chicken, cornstarch, corn flour, corn oil, and lecithin; mono-, di-, and triglycerides; coloring; and citric acid—all of which come from corn. Virtually every processed food contains corn or soy products, including glucose syrup, maltodextrin, and xanthan gum. Corn and soy products are in soups, candies, snacks, cake mixes, gravy, frozen waffles, syrups, hot sauces, mayonnaise, mustard, hot dogs, bologna, margarine, shortening, salad dressings, and relishes. In addition, most beef now comes from cattle raised on feed lots and fed a diet of corn.

Due to these practices, the ratio of omega 6 to omega 3 in the American diet has changed dramatically (Hibbeln et al. 2004, 2006b). Higher ratios of omega 6 to omega 3 have been shown, in correlational and experimental studies, to affect aggressive behavior (Hibbeln et al. 2006a), homicide (Hibbeln 2001), obesity (Hill et al. 2007; Kunešová et al. 2006), heart disease (Bucher et al. 2002), blood pressure (Morris et al. 1993), diabetes (Nettleton and Katz 2005), depression (Hallahan et al. 2007), and cognitive development (Birch et al. 2000).

Marion Nestle (2002) documented marketing practices that increase consumption of unhealthy foods and decrease consumption of healthier ones. For example, thanks in part to aggressive marketing by soft drink companies, schools decreased the amount of milk they buy by nearly 30% between 1985 and 1997, while soft drink purchases by schools rose more than 1,000%. The annual per capita production of milk in the U.S. dropped from 31 gallons in 1970 to only 24 gallons in 1997. Meanwhile, soft drink production rose from 22 to 41 gallons per person (Nestle 2002).

Business Practices Related to Poverty

Prevention scientists also need to study the impact of networks of individuals and organizations whose actions can affect human wellbeing. In this section, I describe practices of a network of conservative business interests that have supported public policies that affect poverty.

The Impact of Poverty in the United States

Poverty is a risk factor for many problems of children and adolescents who, due to living in poverty, become more likely to fail academically and to experience behavioral and psychological problems (McLoyd 1998). Family poverty strains parents and undermines their parenting (Conger et al. 1994; Dodge et al. 1994; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network 2005). Parents under financial strain are less likely to be positively involved with their children and more likely to criticize and argue with them (Gutman et al. 2005). Such perturbed parenting leads to anxious and depressed children and adolescents (Elder et al. 1985; Gutman et al. 2005), school failures (Gutman et al. 2005), aggressive behavior (NICHD 2005), and delinquency (e.g., Weatherburn and Lind 2006).

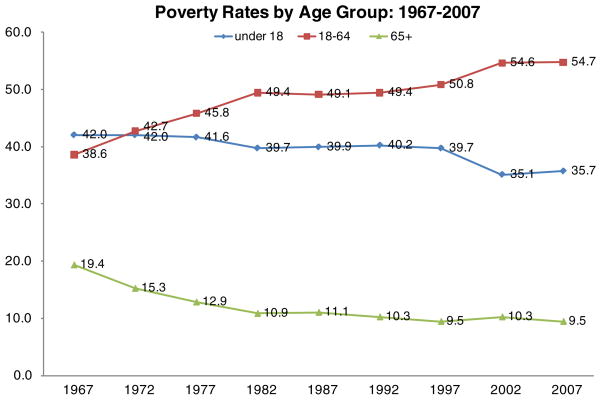

Unfortunately, poverty affects a large number of U.S. children and adolescents. As Fig. 1 shows, the proportion of those under 18 living in poverty surpassed the levels for all other ages until 1972 and has remained above 35% ever since. Among 25 developed countries, the U.S. has the largest proportion of children living in poverty (United Nations Children’s Fund 2007).

Fig. 1.

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements. For information on confidentiality protection, sampling error, nonsampling error, and definitions, see http://www.census.gov/apsd/techdoc/cps/cpsmar08.pdf. Footnotes are available at http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/histpov/footnotes.html.

We cannot solve poverty-related problems solely through programs directed at individuals and families. Education, training, and therapy undoubtedly help some escape poverty (“A youth program” 1995), but as long as U.S. redistributionist policies result in a substantial proportion of Americans living in poverty (Alesina and Glaeser 2004), education, training, and therapy will have a limited impact. One reason is that families living in poverty are less likely to benefit from programs (Reyno and McGrath 2006).

Public policy has a direct impact on poverty. One way to see the importance of policy is to view how it has helped the elderly. Figure 1 shows that the percentage of those over 65 living in poverty steadily declined over the last half of the 20th century, thanks to Social Security and Medicare (http://www.cbpp.org/archiveSite/4-8-99socsec.pdf). However, poverty among children and those between the ages of 18 and 64 has risen due to of a number of factors, including increased single parenting (Fellmeth 2009), a decline in the real value of the minimum wage (Pollin et al. 2008), and an increase in housing costs (Levinson 2004). In a comparison of the policies of European nations with the U.S., Alesina and Glaeser (2004) enumerate European redistributionist policies that contribute to those nations having lower child poverty rates than the U.S.

We could reduce family stress and improve children’s wellbeing through policies that increase families’ economic wellbeing (e.g., Costello et al. 2003). With data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Dahl and Lochner (2005) estimated that a $1,000 increase in family income is associated with a 2.1% increase in math test score standard deviations and a 3.6% increase for reading test scores. A Morris et al. (2004) meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of programs to increase family income concluded that family income positively affects children’s later academic achievement.

Gershoff et al. (2003) identified several policies that increase poor families’ economic wellbeing, including Medicaid, the Earned Income Tax Credit, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, food stamps, federal housing subsidies, the School Lunch Program, and Women, Infants, and Children. The minimum wage also affects family poverty. Unfortunately, it has eroded due to inflation (Whittaker 2003). Robert Pollin at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst Political Economy Research Institute reports that, by 2001, the real value of the national minimum wage of $5.15 per hour was 37% below its peak value of 1968 (Pollin 2002). At the same time, labor productivity rose by 80%. If the inflation-adjusted value of the minimum wage had risen along with these changes, by 2001 it should have been $14.65. Policies that fail to ensure healthcare for all families also affect family poverty: Catastrophic health costs are the number one cause of U.S. bankruptcies (Himmelstein et al. 2005).

The Influence of Some Sectors of the Business Community on Policies that Maintain Poverty

There is evidence that American public policy became less favorable to poor families due to the advocacy of a network of business and advocacy organizations. Lewis Lapham (2004) has described how a 1971 memo from future Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell (at that time a corporate attorney, board member of 11 corporations, and representative for the tobacco industry with the Virginia legislature) to Eugene B. Sydnor, Jr., Chairman of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Education Committee, stimulated the development of conservative advocacy. In it, Powell argued that the business community had failed to make the case for policies favorable to business and that the (then current) low state of public regard for business was a result of their inaction. He advocated that business interests invest in developing a network of organizations and individuals to effectively make the case for business-friendly policies.

In the next 20 years, U.S. business interests followed Powell’s advice. According to Lapham (2004), in 2001, $39 million in scholarships were available to support career development of students friendly to business interests. This included $16 million for students at Harvard, Yale, and the University of Chicago. The network of organizations created to advocate for business-friendly policies include the Heritage Foundation, the American Enterprise Institute, the Cato Institute, the Hoover Institute, the Hudson Institute, the Manhattan Institute, Citizens for a Sound Economy, the National Center for Policy Analysis, the Competitive Enterprise Institute, the Free Congress Foundation, the Business Roundtable, and the Federalist Society.

These organizations support the writing, publication, and promotion of books, magazine articles, op-ed pieces, and papers in scholarly journals that advocate viewpoints favorable to limited government regulation and taxation. Think tanks (e.g., the American Enterprise Institute) support scholarship and advocacy and produce reports, newsletters, briefs, and op-ed pieces that dominate public discussion. Lapham estimated that the 2001 budgets of the major pro-business think tanks totaled $136 million. A steady stream of opinion leaders who work for these groups or who receive support from them regularly participate on television news and talk shows and influence public opinion to be favorable to the needs and interests of business.

Huge changes have occurred in the nature of public discussion and public opinion due to these efforts. The antibusiness rhetoric described in the 1971 Powell Memorandum has given way to widespread support for policies that limit government regulation and taxation, reduce government support for families living in poverty, and fail to provide healthcare coverage for millions. (Since I wrote these paragraphs, the economic crisis in this country has harmed the wellbeing of many more Americans. These new problems are additional consequences of the economic and regulatory policies I just described. The current crisis underscores the importance of behavioral scientists understanding not simply the actions of individual corporations, but the actions of networks of organizations working for their common business interests.)

Of course, the evidence I present here on the role that business organizations have in these changes provides at best a case study. But it should encourage anyone concerned with the harm caused by recent economic policies to investigate closely the role of business and advocacy organizations in promoting those policies. To the extent that they contribute to public health problems, the policies—and the practices maintaining them—are just as legitimate for prevention research to target as classroom aggression is (Pechmann and Ratneshwar 1994). It is possible to conduct more sophisticated analyses: For example, time-series analyses could examine the relationship between changes in advocacy for deregulation or opposition to redistributive policies and changes in those policies.

An Evolutionary Framework

Understanding the role that corporate practices play in human wellbeing requires a conceptual framework. Evolutionary theory provides a useful one. There is a large and growing literature on the evolution of cultural practices (e.g., Diamond 1999, 2004; Glenn 2004; Harris 1974; Ponting 1991; Wilson 2003; Wilson and Sober 1994). The fundamental insight is that practices are selected by their consequences in much the same way that individual behavior is selected by its consequences (Biglan 2003). Practices that increase profits and other material resources for organizations are apt to expand, while those that harm profits will be abandoned. In this view, we can change what corporations do by modifying the consequences of their actions.

Perhaps the best example of these processes is the evolution of tobacco industry marketing and public relations practices and the subsequent evolution of the tobacco control movement. In both cases, practices were adopted, enhanced, or abandoned based on the consequences. For the industry, the primary consequences were market share and profits. For the tobacco control movement, it was primarily their impact on smoking prevalence.

The Evolution of Tobacco Industry Practices

Pierce and Gilpin (1995) analyzed the evolution of tobacco company marketing practices during the 20th century in terms of their impact on market share. They document how each major increase in the prevalence of smoking was due to a carefully targeted advertising campaign. The success of each campaign reinforced its practices and over time the tobacco companies’ marketing became increasingly sophisticated.

Similarly, tobacco companies’ lobbying and public relations practices were selected by their consequences (Biglan 2004; Biglan et al. 2004; NCI 2008). The industry created the Tobacco Institute to protect itself from adverse governmental action. In U.S. v. Philip Morris et al. (2006), the court found that the industry had colluded to deceive the public about the harmfulness of cigarettes and about the companies’ marketing to teens. The effort was quite effective: For 50 years, smokers continued to die in ever-greater numbers, but for most of that time, tobacco marketing continued unrestricted.

Documents from 1980 through the late 1990s show that the tobacco companies created youth smoking prevention programs that had no impact on youth smoking, but were successful in dissuading lawmakers from restricting cigarette advertising (Biglan 2004). This is precisely what an analysis of economic contingencies would predict. Truly preventing youth smoking would have harmed tobacco company profits dramatically (Biglan 2004). However, convincing lawmakers that the companies were preventing youth smoking prevented placement of restrictions on their youth marketing, which, as their documents show (Biglan 2004), would have reduced their profits significantly.

The Evolution of Tobacco Control Practices

The first empirical evidence of smoking’s harmfulness arose in 1950 when Ernst Wynder showed that tobacco smoke caused cancer (Wynder and Graham 1950). Thus began the evolution of the tobacco control movement, which Bonnie et al. (2007) labeled “one of the 10 greatest achievements in public health in the 20th century…” The success of the tobacco control movement resulted from four interlocking activities (Biglan and Taylor 2000): communicating epidemiological evidence, empirically evaluating tobacco control strategies, advocating for tobacco control, and ongoing surveillance of tobacco use and practices that influence tobacco use.

Obtaining and Communicating Epidemiological Evidence About the Problem of Tobacco Use

Fundamental to tobacco control has been an evolving network of empirical facts about the harm of smoking, which motivated an increasing number of people and organizations to work against tobacco use. Public health researchers pinpointed health consequences of smoking, documented the prevalence and cost of smoking, and identified a growing list of risk factors associated with starting and continuing to smoke. As noted above, researchers focused increasingly on tobacco company marketing practices as risk factors for adolescents beginning to smoke and for adults continuing to smoke (Biglan 2004; NCI 2008).

Tobacco control advocates have found innovative ways to illustrate the harm of tobacco use. For example, they often say, “Cigarette smoking is the number one preventable cause of disease and death. It kills about 450,000 people a year in this country—as if two Boeing 747s crashed, killing everyone on board, every day of the week” (Centers for Disease Control 2002). Such vivid images helped to change the public perception of smoking and generated public support that has been vital to the growth and effectiveness of the tobacco control movement.

Empirically Evaluating Strategies for Tobacco Control

Tobacco control researchers began to accumulate effective methods for reducing smoking. The initial focus was on smoking cessation, but it soon became apparent that few smokers would utilize organized programs and that bringing about significant reductions in the prevalence of smoking required strategies with a more public health-oriented approach (Lichtenstein and Glasgow 1992). Strategies have involved demand reduction, through media campaigns; school-based prevention programs; advocacy for clean indoor air regulation; and increased taxation (NCI 2008). As evidence mounted of the role tobacco marketing played in the prevalence of smoking, research on how to counter these practices grew. Saffer and Chaloupka (2000) concluded that a complete ban on cigarette advertising could reduce demand. Media campaigns directed at youth, which vilify tobacco company marketing practices, have shown benefit in preventing youth smoking (Farrelly et al. 2005; Hersey et al. 2005; Thrasher et al. 2004).

Advocating

Perhaps the most important reason for the success of the tobacco control movement has been the growth and effectiveness of its advocacy (Biglan and Taylor 2000). Initially the American Cancer Society, American Lung Association, and American Heart Association conducted media campaigns to prompt smokers to quit. As awareness of smoking’s harmfulness increased and knowledge of its harm spread throughout the population, people were motivated to create organizations such as the Americans for Nonsmokers Rights and the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. As research showed the value of policies such as clean indoor air laws and increased taxes, these organizations began to advocate for such policies. At the same time, support for the organizations increased due to the perception that people’s actions could contribute to less smoking and, thereby, to less disease.

Advocacy organizations have conducted media campaigns, some of which attacked the tobacco companies. These efforts harmed the credibility of the tobacco companies, thus undermining the companies’ public relations and lobbying. Lawsuits by private parties and the states’ Attorneys General have imposed considerable costs on tobacco companies and have resulted in restrictions on marketing. (However, judging from the share prices of the tobacco companies and the judgments of Wall Street analysts [Martin 2007], the damage awards and marketing restrictions have not significantly reduced the profitability of the tobacco business.)

Surveillance

As with other public health problems, an extensive surveillance system guides tobacco control efforts. The system began with monitoring smoking prevalence among nationally representative samples of adults and adolescents. As understanding grew of the influences on tobacco and of the programs and policies to reduce tobacco use, the system began to include monitoring influences on programs and policies. For example, the tobacco control community now monitors: (a) the marketing expenditures of the tobacco companies, (b) state expenditures on tobacco control, (c) adolescent access to tobacco, and (d) quit rates among smokers. Such information has been vital in guiding and motivating tobacco control efforts.

The Importance of Selecting Consequences

Tobacco control practices evolved because of their consequences. At first, they were selected by their success in getting people and organizations to support further tobacco control efforts and by their impact on the prevalence of smoking. As understanding of smoking’s harmfulness grew, the victims of smoking and their loved ones gave money and supported government and private organizations that worked against smoking. As research and public understanding of the problem grew, tobacco control activities increased or disappeared depending on their impact on smoking prevalence.

The success of the tobacco control movement could have been more rapid and more substantial, however, if an evolutionary analysis had guided it. The fundamental contingency that drives tobacco industry practices is the impact of those practices on profits. The tobacco control movement seems to have had only a vague understanding of the importance of this contingency. For example, when the Attorneys General of 46 states sued the tobacco companies over the contribution to the illnesses of states’ Medicare patients, settlement talks ensued. One provision of settlement that the AGs proposed was a “look-back” provision, in which tobacco companies would have to pay money to the states for every young person who began smoking. (The surveillance system provides yearly estimates of the number of young people who have begun smoking.) The provision was eventually dropped due to tobacco company insistence.

This provision would have reached the heart of the problem. The tobacco industry must recruit new smokers in order to maintain its profits (Biglan 2004). A look-back provision would have meant that the tobacco companies would lose money by getting new smokers. Although the settlement agreement that was eventually reached put some restrictions on tobacco company marketing, the companies continue to profit from recruiting new smokers.

Consequences Selecting Other Corporate Practices

In the same way, we can analyze marketing practices of the alcohol and food industries in terms of the consequences that affect their evolution. The harmful practices I describe above have been selected by their success in selling their products and in preventing restrictions on their marketing practices. For example, the food industry did not set out to make people obese or to change people’s omega 3 levels. These results are byproducts of the evolution of food production and marketing. As the per-acre productivity of corn and soybeans increased, it put downward pressure on the price of these commodities (Pollan 2006). One effect was to stimulate further increases in productivity, which provided immediate increases in growers’ profits, but over time, simply reduced prices further. Another effect was to find new uses for corn and soy products, such as high fructose corn syrup and soybean oil. Similarly, food marketers had incentives to sell as many of their products as possible. Soft drink consumption rose and milk consumption plummeted when soft drink marketers began to sign exclusive contracts with schools. Nestle (2002) quotes a Colorado school administrator who labeled himself the ‘Coke dude.’ He stated, “We must sell 70,000 cases of product…at least once during the first three years….If 35,439 staff and students buy one Coke product every other day for a school year, we will double the required quota. Here is how we can do it…Allow students to purchase and consume vended products throughout the day…” (Nestle, p. 205)

The threat of restrictions on marketing affects corporate practices because it threatens their profits. The alcohol industry recently increased its advertising about responsible drinking because it understands from the tobacco lawsuits that it must prevent the public from perceiving that it markets to youth. Nevertheless, as long as it is legal and profitable to market to a youthful audience, the industry will continue to do so.

An evolutionary analysis indicates that, in order to alter harmful corporate practices, we need to alter the consequences of those practices. For example, Michael Pollan (2007) recently pointed out that the low cost of high calorie foods with little nutritional value is due, in part, to federal subsidies for production of corn and soybeans. It is likely—and surely worthy of evaluation—that reducing these subsidies would reduce the consumption of unhealthy foods. Increasing subsidies for healthful foods such as fruits and vegetables should have the same effect and might engender less opposition from the food industry. Brownell and Horgen (2004) proposed taxing junk food. Courts may eventually hold companies that make fattening foods liable for their production and marketing practices.

We can also understand the evolution of policies unfavorable to poor people in terms of selection by consequences. Lewis Powell’s memo was a stimulus to advocate for low taxes and little regulation, but the policy successes that resulted produced specific economic benefits to those who supported the effort. The profitability of these developments for American business is evident in the fact that, unlike previous business cycles, in the recession-and-return-to-growth cycle in 2001, corporate profits increased at a much greater rate than did the incomes of lower paid Americans. Indeed, disparities in wealth and income are higher in the U.S. than they have been since the Gilded Age of the late 19th century (Krugman 2007).

From one perspective, the notion that consequences influence corporate practices may seem obvious. But it is not obvious to those who have been regulating financial markets. I recall thinking, “Uh oh,” when I read in 2007 that the auditors who were valuing mortgage-backed securities were receiving payment from the holders of those securities. Subsequent reports revealed that auditors felt pressured by their superiors to inflate the value of these securities (Bajaj 2008); further, business depended on it. The crash of 2008 was the direct result of the over-valued derivative investments that had flooded the market thanks to the huge rewards that could be reaped by those who sold them (Gwartney et al. 2009).

Ultimately, we need research on the impact of consequences on corporate practices, especially studies of the effect of altering consequences. One example of the creative use of contingencies to control problematic corporate practices is Sugarman’s (2005) concept of performance-based regulation. In this scheme, companies must gradually reduce the harm their practices produce but may do so any way they can devise. They pay a penalty for failing to achieve the necessary harm-reduction targets. This goes to the heart of the contingency between corporate practices by making a practice’s cost greater than its benefit. Prevention scientists could work with policymakers to provide experimental analyses of the impact of such policies.

The Need for Advocacy Organizations

This conclusion, however, leads to a new difficulty: how to achieve the power and influence to alter contingencies that select harmful corporate practices. Even if we can show that altering the consequences of corporate actions influences those actions, how do we influence citizens and policymakers to do so?

The tobacco control movement is instructive. It shows that industries strive to continue profitable yet harmful practices, but concerted advocacy can countervail these efforts.

In general, countervailing the influence of harmful corporate practices will require strengthening the effectiveness of existing advocates and enlisting new organizations into the effort (Biglan 2009). Organizations such as Americans for Nonsmokers Rights, the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, the American Legacy Foundation, and numerous local organizations that the tobacco control movement has spawned have been critical in changing public policy in the tobacco arena. In the alcohol arena, organizations such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) have led the way in changing policies regarding drunken driving.

Prevention research is vital to these developments. Just as prevention scientists work to improve the effectiveness of families and schools, they can increase the effectiveness of organizations that alert the public to harmful practices and advocate for policies to prevent these practices. We need to study the range of advocacy groups working on public health, their topics of focus, their strategies, and most importantly, the amount and sources of their funding.

Research is also necessary on how to increase the effectiveness of advocacy organizations. One concern is with increasing the effectiveness and reach of persuasive communications. Some evidence indicates that media can influence public policymaking (Wallack and Dorfman 1996) and individual health behavior (e.g., Flay 1987), yet I know of only one experimental evaluation on the use of media to influence policymaking (Fawcett et al. 1987), and that involved simply sending letters to policymakers.

A second way prevention researchers could contribute is through research on financial support for advocacy organizations. Elsewhere I have outlined steps to strengthen advocacy organizations (Biglan 2009). First we must recognize that even practices of nonprofit advocacy groups are selected by consequences. If we want to increase the number, size, and effectiveness of organizations advocating for public health, we will need to make public policies more favorable for these organizations receiving funds. This will require more analysis and public discussion of precisely which nonprofit activities benefit public wellbeing. Then, we will need to adopt policies that support those activities. Such policies might include: (a) increased tax benefits for giving to organizations engaged in improving public health; (b) greater accountability, so that the activities and impact of such advocacy organizations are transparent; and (c) government funding of advocacy organizations that are working to counter corporate practices causing well-established harm. For example, given that depicting smoking in movies influences adolescents to smoke (Sargent et al. 2001, 2002) and given that Pechmann and Shih (1999) have shown that a brief antismoking message preceding a movie can eliminate the impact of smoking depictions in movies, it would be appropriate for the government to fund advocacy organizations to place such spots in movie theaters.

Recommendations for Prevention Science

For many readers, it may seem hopelessly idealistic to try to influence harmful organizational practices. However, our typical time horizon for thinking about cultural change may limit our aspirations. The evolution of sanitation practices provides an example.

Steven Johnson (2006) describes the conditions in London in the 1840s and 50s. Although London was the largest and wealthiest city in the world, few of its homes had connections to any sewer system; urine and excrement simply collected in cellars and yards. The result was continuing deaths due to cholera—a disease then believed to be due to bad air.

In the late 1840s, John Snow developed the hypothesis that contaminated water was the cause of cholera. Initially, others ridiculed his theory. However, an outbreak of cholera in his own neighborhood provided the opportunity to test his hypothesis empirically. The outbreak began on August 31, 1854; by September 10, it had killed 500 people. Snow and a local minister, Henry Whitehead, investigated each death in order to determine where the victims had obtained their water. They found that each victim for whom they could obtain information had drunk water from the pump on Broad Street. Snow convinced community leaders to remove the pump handle. The epidemic immediately abated.

The classic lesson from this story is that we protect public health when we identify key risk factors for disease and move, pragmatically, to alter them. However, there is one other important lesson from the Broad Street pump: Practices we now find appalling were once commonplace and accepted. Perhaps prevention science can make the prevention of harmful corporate practices as fundamental to society as sanitation now is.

To sum up, prevention science can move society forward by expanding its research agenda as follows:

Systematically research the impact of corporate practices on each of the most common and costly psychological, behavioral, and health problems.

Empirically analyze the factors that select harmful corporate practices and identify ways to alter the consequences of such practices.

Assess the impact of policies that would affect problematic corporate practices.

-

Study advocacy organizations to

understand the factors that influence their growth and effectiveness;

develop and evaluate effective strategies for them to have a direct influence on corporate externalities and to affect public policies that will affect corporate externalities.

Acknowledgments

The National Cancer Institute (Grant CA-38273) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant P30 DA018760) provided financial support for the completion of the work on this manuscript. The author wishes to thank Christine Cody for her editorial input and assistance with references.

Footnotes

The author based this paper on his Presidential Address at the Society for Prevention Research Annual Meeting in 2007.

References

- Agostinelli G, Grube JW. Alcohol counter-advertising and the media: A review of recent research. Alcohol Research & Health. 2002;26:15–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken PP, Eadie DR, Hastings GB, Haywood AJ. Predisposing effects of cigarette advertising on children’s intentions to smoke when older. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:383–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb03415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alesina A, Glaeser EL. Fighting poverty in the US and Europe: A world of difference. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander HM, Callcott R, Dobson AJ, Hardes GR, Lloyd DM, O’Connell DL, et al. Cigarette smoking and drug use in schoolchildren: IV–Factors associated with changes in smoking behaviour. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1983;12:59–66. doi: 10.1093/ije/12.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong BK, de Klerk NH, Shean RE, Dunn DA, Dolin PJ. Influence of education and advertising on the uptake of smoking by children. The Medical Journal of Australia. 1990;152:117–124. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1990.tb125117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Adolescents’ responses to cigarette advertisements for five “youth brands” and one “adult brand”. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:425–443. [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Tercyak KP, Shields AE, Bush A, Espinel CF, Lerman C. Which adolescents are most receptive to tobacco industry marketing? Implications for counter-advertising campaigns. Health Communication. 2003;15:499–513. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1504_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A youth program that worked (Editorial) New York Times; 1995. Mar 20, [Accessed 9/10/07]. http://www.eisenhowerfoundation.org/aboutus/media/NYTimesAyouthprogramWorkedMar95.html. [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj V. Inquiry assails accounting firm in lender’s fall. New York Times; 2008. Mar 27, [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, Siegel M. Tobacco marketing and adolescent smoking: More support for a causal inference. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:407–411. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A. Selection by consequences: One unifying principle for a transdisciplinary science of prevention. Prevention Science. 2003;4:213–232. doi: 10.1023/a:1026064014562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A. Direct written testimony in the case of the U.S.A. vs. Phillip Morris et al. U.S. Department of Justice; 2004. [On-line]. Available: http://www.ori.org/oht/testimony.html. [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A. The role of advocacy organizations in reducing negative externalities. Invited paper for Special Issue of Journal of Behavioral Management. 2009;29:1–16. doi: 10.1080/01608060903092086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Taylor TK. Why have we been more successful in reducing tobacco use than violent crime? American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:269–302. doi: 10.1023/A:1005155903801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Brennan PA, Foster SL, Holder HD. Helping adolescents at risk: Prevention of multiple problem behaviors. New York: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Birch EE, Garfield S, Hoffman DR, Uauy R, Birch DG. A randomized controlled trial of early dietary supply of longchain polyunsaturated fatty acids and mental development in term infants. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2000;42:174–181. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200000311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnie RJ, Stratton K, Wallace RB Committee on Reducing Tobacco Use. Ending the tobacco problem: A blueprint for the nation. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell KD, Horgen KB. Food fight: The inside story of the food industry, America’s obesity crisis, and what we can do about it. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher H, Hengstler P, Schindler C, Meier G. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The American Journal of Medicine. 2002;112:298–304. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)01114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs—United States, 1995–1999. MMWR. 2002;51:300–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton A, Blair V. Predicting the onset of smoking in boys and girls. Social Science & Medicine. 1989;29:813–18. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Cruz TB, Schuster DV, Unger JB, Johnson CA. Receptivity to protobacco media and its impact on cigarette smoking among ethnic minority youth in California. Journal of Health Communication. 2002;7:95–111. doi: 10.1080/10810730290087987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WS, Ahluwalia JS, Harris KJ, Okuyemi K. Progression to established smoking: The influence of tobacco marketing. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22:228–233. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00420-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ge X, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development. 1994;65:541–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Compton SN, Keeler G, Angold A. Relationships between poverty and psychopathology: A natural experiment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:2023–2029. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl G, Lochner L. IRP discussion paper no. 1305–05. Madison, WI: Institute for Research on Poverty; 2005. The impact of family income on child development. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond J. Guns, germs, and steel: The fates of human societies. New York: Norton; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond J. Collapse: How societies choose to fail or succeed. New York: Viking Adult; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Socialization mediators of the relation between socioeconomic status and child conduct problems. Child Development. 1994;65:649–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan RJ, Jancey J, Jones S. Tobacco point of sale advertising increases positive brand user imagery. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:191. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.3.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Jr, Nguyen TV, Caspi A. Linking family hardship to children’s lives. Child Development. 1985;56:361–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans N, Farkas A, Gilpin E, Berry CC, Pierce JP. Influence of tobacco marketing and exposure to smokers on adolescent susceptibility to smoking. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1995;87:1538–1545. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.20.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly MC, Davis KC, Haviland ML, Messeri P, Healton CG. Evidence of a dose-response relationship between “truth” antismoking ads and youth smoking prevalence. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:425–431. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett SB, Seekins T, Jason LA. Policy research and child passenger safety legislation: A case study and experimental evaluation. Journal of Social Issues. 1987;43:133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Feighery E, Borzekowski DLG, Schooler C, Flora J. Seeing, wanting, owning: The relationship between receptivity to tobacco marketing and smoking susceptibility in young people. Tobacco Control. 1998;7:123–128. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellmeth RC. Child poverty in the United States: The need for a constitutional amendment and a cultural sea change. American Bar Association Human Rights Magazine; 2009. [Accessed September 29, 2009]. online. at http://www.abanet.org/irr/hr/winter05/childpovertyinus.html. [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR. Selling the smokeless society: 56 evaluated mass media programs and campaigns worldwide. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Aber JL, Raver CC. Child poverty in the United States: An evidence-based conceptual framework for programs and policies. In: Jacobs F, Wertlieb D, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of applied developmental science: Promoting positive child, adolescent, and family development through research, policies, and programs. Vol. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 81–136. [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin EA, White MM, Messer K, Pierce JP. Receptivity to tobacco advertising and promotions among young adolescents as a predictor of established smoking in young adulthood. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1489–1495. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.070359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn SS. Individual behavior, culture, and social change. Behavior Analyst. 2004;27:133–151. doi: 10.1007/BF03393175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grube JW. Alcohol in the media: Drinking portrayals, alcohol advertising, and alcohol consumption among youth. In: Bonnie R, O’Connell ME, editors. Reducing underage drinking: A collective responsibility, background papers [CD-ROM]. Committee on developing a strategy to reduce and prevent underage drinking. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, McLoyd VC, Tokoyawa T. Financial strain, neighborhood stress, parenting behaviors, and adolescent adjustment in urban African American families. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;15:425–449. [Google Scholar]

- Gwartney J, Macpherson D, Sobel R, Stroup R. [Accessed October 3, 2009];Special topic: Crash of 2008. 2009 Available online. at http://www.commonsenseeconomics.com/Activities/Crisis/CSE.CrashOf2008.pdf.

- Hallahan B, Hibbeln JR, Davis JM, Garland MR. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in patients with recurrent self-harm: Single-centre double-blind randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;190:118–122. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.022707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M. Cows, pigs, wars, witches: The riddles of culture. New York: Random House; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L, Flora JA, Feighery E, Fortmann SP. Effects on youth exposure to retail tobacco advertising. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;32:1771–1789. [Google Scholar]

- Hersey JC, Niederdeppe J, Ng SW, Mowery P, Farrelly M, Messeri P. How state counter-industry campaigns help prime perceptions of tobacco industry practices to promote reductions in youth smoking. Tobacco Control. 2005;14:277–383. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.010785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbeln JR. Seafood consumption and homicide mortality. A cross-national ecological analysis. World Review of Nutrition & Dietetics. 2001;88:41–46. doi: 10.1159/000059747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbeln JR, Nieminen LR, Lands WE. Increasing homicide rates and linoleic acid consumption among five Western countries, 1961–2000. Lipids. 2004;39:1207–1213. doi: 10.1007/s11745-004-1349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbeln JR, Ferguson TA, Blasbalg TL. Omega-3 fatty acid deficiencies in neurodevelopment, aggression and autonomic dysregulation: Opportunities for intervention. International Review of Psychiatry. 2006a;18:107–118. doi: 10.1080/09540260600582967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbeln JR, Nieminen LR, Blasbalg TL, Riggs JA, Lands WE. Healthy intakes of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids: Estimations considering worldwide diversity. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006b;83:1483S–1493S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1483S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AM, Buckley JD, Murphy KJ, Howe PR. Combining fish-oil supplements with regular aerobic exercise improves body composition and cardiovascular disease risk factors. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;85:1267–1274. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelstein D, Warren E, Thorne D, Woolhander S. Illness and injury as contributors to bankruptcy. Health Affairs Web Exclusive. 2005;W5–63:02. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. The ghost map. New York: Riverhead Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman NJ, Castrucci BC, Mowery PD, Gerlach KK, Emont S, Orleans CT. Predictors of change on the smoking uptake continuum among adolescents. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156:581–587. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krugman P. Gilded once more. The New York Times; 2007. Apr 27, Editorial section. [Google Scholar]

- Kunešová M, Braunerová R, Hlavatý P, Tvrzická E, Staòková B, Škrha J, et al. The influence of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and very low calorie diet during a short-term weight reducing regimen on weight loss and serum fatty acid composition in severely obese women. Physiological Research. 2006;55:63–72. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.930770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M, Wechsler H, Greenberg P, Lee H. The marketing of alcohol to college students: The role of low prices and special promotions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25:204–211. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapham L. Tentacles of rage. Harper’s Magazine; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson D. Encyclopedia of homelessness. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein E, Glasgow RE. Smoking cessation: What have we learned over the past decade? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:739–744. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez ML, Herrero P, Comas A, Leijs I, Cueto A, Charlton A, et al. Impact of cigarette advertising on smoking behaviour in Spanish adolescents as measured using recognition of billboard advertising. European Journal of Public Health. 2004;14:428–432. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/14.4.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A. As Altria sheds Kraft, Wall Street cheers: As Altria sheds Kraft Foods, tobacco giant’s shares gain. International Herald Tribune, Business; 2007. Jan 31, [Last accessed August 29, 2007]. at http://www.iht.com/articles/2007/01/31/business/tobacco.php. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. The American Psychologist. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MC, Sacks F, Rosner B. Does fish oil lower blood pressure? A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Circulation. 1993;88:523–533. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.2.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris P, Duncan GJ, Rodrigues C. Does money really matter? [Last accessed September 19, 2008];Estimating impacts of family income on children’s achievement with data from random-assignment experiments. 2004 doi: 10.1037/a0023875. at http://depts.washington.edu/crfam/seminarseries03-04/MorrisDuncanRodrigues_Feb04.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. The role of the media in promoting and discouraging tobacco use (NCI Tobacco Control Monograph 19) Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among Children, Youth, and Young Adults: Research Advances and Promising Interventions. In: O’Connell ME, Boat T, Warner KE, editors. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson J. Advertising bans, monopoly, and alcohol demand: Testing for substitution effects using state panel data. Review of Industrial Organization. 2003;22:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Nestle M. Food politics: How the food industry influences nutrition and health (California studies in food and culture) Berkeley: University of California Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nettleton JA, Katz R. N-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in type 2 diabetes: A review. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105:428–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Childcare and child development: Results from the NICHD study of early childcare and youth development. Washington, DC: NICHD Early Child Care Research Network; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. [Accessed May 2, 2008];Glossary of statistical terms: Externalities. 2008 at http://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=3215.

- Pechmann C, Knight SJ. An experimental investigation of the joint effects of advertising and peers on adolescents’ beliefs and intentions about cigarette consumption. Journal of Consumer Research. 2002;29:5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pechmann C, Ratneshwar S. The effects of antismoking and cigarette advertising on young adolescents’ perceptions of peers who smoke. Journal of Consumer Research. 1994;21:236–251. [Google Scholar]

- Pechmann C, Shih C. Smoking scenes in movies and antismoking ads before movies: Effects on youth. Journal of Marketing. 1999;63:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Gilpin EA. A historical analysis of tobacco marketing and the uptake of smoking by youth in the United States: 1890–1977. Health Psychology. 1995;4:500–508. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.6.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Berry CC. Tobacco industry promotion of cigarettes and adolescent smoking. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279:511–515. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.7.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Distefan JM, Jackson C, White MM, Gilpin EA. Does tobacco marketing undermine the influence of recommended parenting in discouraging adolescents from smoking? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23:73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollan M. The omnivore’s dilemma. New York: Penguin USA; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pollan M. Unhappy meals. The New York Times; 2007. Jan 28, [Accessed September 10, 2007]. Magazine online. at http://www.michaelpollan.com/article.php?id=87. [Google Scholar]

- Pollin R. What is a living wage? Considerations from Santa Monica, California. Review of Radical Political Economics. 2002 Fall;:267–73. [Google Scholar]

- Pollin R, Brenner MD, Wicks-Lim J, Luce S. A measure of fairness: The economics of living wages and minimum wages in the United States. Amherst, MA: Political Economy Research Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ponting C. A green history of the world: The environment and the collapse of great civilizations. New York: Penguin; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pucci LG, Siegel M. Exposure to brand-specific cigarette advertising in magazines and its impact on youth smoking. Preventive Medicine. 1999;29:313–320. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyno SM, McGrath PJ. Predictors of parent training efficacy for child externalizing behavior problem—a meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:99–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffer H, Chaloupka F. The effect of tobacco advertising bans on tobacco consumption. Journal of Health Economics. 2000;19:1117–1137. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(00)00054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffer H, Dave D. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 9676. 2003. Alcohol advertising and alcohol consumption by adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Dalton M, Beach M. Exposure to cigarette promotions and smoking uptake in adolescents: Evidence of a dose-response relation. Tobacco Control. 2000a;9:163–168. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Dalton M, Beach M, Bernhardt A, Heatherton T, Stevens M. Effect of cigarette promotions on smoking uptake among adolescents. Preventive Medicine. 2000b;30:320–327. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Beach ML, Dalton MA, Mott LA, Tickle JJ, Ahrens MB, et al. Effect of seeing tobacco use in films on trying smoking among adolescents: Cross sectional study. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2001;323:1394–1399. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7326.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Dalton MA, Beach ML, Mott LA, Tickle JJ, Ahrens MB, et al. Viewing tobacco use in movies: Does it shape attitudes that mediate adolescent smoking? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00434-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman SD. Let’s try performance-based regulation to attack our smoking and obesity problems. Boalt Hall Transcript. 2005;38:30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Tercyak KP, Goldman P, Smith A, Audrain J. Interacting effects of depression and tobacco advertising receptivity on adolescent smoking. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:145–154. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher JF, Niederdeppe J, Farrelly MC, Davis KC, Ribisl KM, Haviland ML. The impact of anti-tobacco industry prevention messages in tobacco producing regions: Evidence from the US truth® campaign. Tobacco Control. 2004;13:283–288. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triggle N. Doctors want booze marketing ban. BBC Health News; 2009. Sep 9, [Last accessed October 29, 2009]. online. at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/8242385.stm. [Google Scholar]

- Turco RM. Effects of exposure to cigarette advertisements on adolescents’ attitudes toward smoking. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1997;27:1115–1130. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Innocenti Report Card 7. Florence, Italy: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre; 2007. Child Poverty in perspective: An overview of child well-being in rich countries. [Google Scholar]

- United States v. Philip Morris et al., Civil No. 99-CV-02496GK (U.S. Dist. Ct., DC, 2006).

- Unger JB, Chen X. The role of social networks and media receptivity in predicting age of smoking initiation: A proportional hazards model of risk and protective factors. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24:371–381. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Cruz TB, Schuster D, Flora JA, Johnson CA. Measuring exposure to pro- and anti-tobacco marketing among adolescents: Intercorrelations among measures and associations with smoking status. Journal of Health Communication. 2001;6:11–29. doi: 10.1080/10810730150501387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Current population survey, 1960–2002. Annual social and economic supplements. 2003 Available online at http://www.uscensus.gov.

- Wallack L, Dorfman L. Media advocacy: A strategy for advancing policy and promoting health. Health Education Quarterly. 1996;23:293–317. doi: 10.1177/109019819602300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherburn D, Lind B. What mediates the macro-level effects of economic and social stress on crime? The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology. 2006;39:384–397. [Google Scholar]

- While D, Kelly S, Huang W, Charlton A. Cigarette advertising and onset of smoking in children: Questionnaire. British Medical Journal. 1996;31:398–399. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7054.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker WG. Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress; 2003. The federal minimum wage and average hourly earnings of manufacturing production workers (CRS report for Congress) Available at Digital Commons @ ILR, Cornell University ILR School. Accessed September 19, 2008 at http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1237&context=key_workplace. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DS. Darwin’s cathedral. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DS, Sober E. Reintroducing group selection to the human behavioral sciences. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1994;17:585–654. [Google Scholar]

- Wynder EL, Graham EA. Tobacco smoking as a possible etiologic factor in bronchiogenic carcinoma: A study of 684 proved cases. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1950;143:329–336. doi: 10.1001/jama.1950.02910390001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]