Abstract

Individuals with asthma living in the inner city experience increased asthma morbidity and mortality compared to the US average. The Controlling Asthma in America’s Cities Project’s Chicago site used a multifaceted approach to improve asthma care. The diverse scope of this project’s interventions necessitated the use of novel methods to assess the effect of these interventions on the entire study area. Asthma-related medication-dispensing data were obtained from a large pharmacy chain for prescriptions filled in calendar years 2004–2006 for all individuals aged 5–17 years living in Chicago who filled at least four asthma-related medications within a 12-month period. Inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) use was considered inadequate if an individual had four or more dispensings of a short-acting beta-agonist without at least four dispensings of an ICS agent. Logistic regression was used to compare adequate ICS use in individuals within the intervention area with ICS use in the remainder of the city, after controlling for gender, insurance status, race, and poverty. A significant difference in adequate ICS use was found in years 2 (2005) and 3 (2006) of the project for individuals aged 5–9 in the intervention area (odds ratios for adequate ICS use—year 2, 1.26; CI, 1.04–1.53, p = 0.04; year 3, 1.30; CI, 1.08–1.55, p = 0.008) compared to individuals aged 5–9 in the remainder of the city. There was no similar significant difference in the 10–17 age group. These findings suggest an effect of a large multifaceted asthma intervention in improving medication use in the targeted age group. This methodology might also prove useful in the future for assessing the effect of similar interventions.

Keywords: Asthma outcomes, Pharmicoepidemiology, Asthma intervention

Introduction

Individuals with asthma living in the inner city have a disproportionate health burden due to their disease.1,2 In Chicago, asthma morbidity varies substantially with socioeconomic status, and racial disparities are apparent in both hospitalization rates and asthma mortality.1

Although various metrics, such as surveys assessing asthma knowledge among persons participating in case management, could be used to evaluate individual components of an asthma intervention program, these metrics do not capture aggregate community-wide effects. Population-based indicators of health care utilization (hospital and emergency department visits) are often influenced by factors unrelated to the project and are relatively rare on a small area scale. Medication prescription-dispensing data provide intermediate outcomes that can be useful for community-wide assessment.3,4 Previous work has demonstrated that pharmacy data accurately reflect adherence when compared with a manual review of written prescriptions.5 Asthma-related medication-dispensing data have been shown to be useful surrogates for asthma morbidity.6 Furthermore, an asthma-control scale based on pharmacy data for asthma medication dispensings has been shown to be a valid mechanism for identifying patients at risk for acute asthma.7 None of these studies used prescription-dispensing data to examine directly the effects of a large intervention. The studies were encouraging, however, regarding pharmacy data’s potential for assessing the effects of the diverse interventions implemented by the Chicago site of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-funded Controlling Asthma in America’s Cities Program (CAACP). This analysis used such an approach to compare changes in the appropriate use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) for those living within the intervention area with those living in the remainder of Chicago.

Methods

CAACP Interventions

Through the CAACP, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention partnered with researchers and community-based coalitions in seven cities throughout the USA to translate scientific knowledge into public health practices for the purpose of reducing the burden of asthma in populations of need. The project for the Chicago site extended from July 2003 to June 2008 and used a multifaceted approach to improve asthma care for inner city children (ages 0–18 years). Individual components of the project included identification of children with asthma through the administration of a validated questionnaire in the schools, followed by individualized interventions for child with diagnosed asthma or symptoms consistent with asthma. One of the interventions provided asthma self-management training and the reduction of indoor asthma triggers in the home through a series of three or four home visits conducted by community (lay) educators. Additional education programs in schools and at community events, including the American Lung Association’s Open Airways Program8,9 for children and the Asthma 101 Program for teachers, staff, and other adults, also addressed asthma self-management and environmental factors affecting the disease. For these individuals, providers on mobile care vans confirmed the diagnosis of asthma, devised an asthma management plan, provided asthma education and medication, and follow up education and care as needed. Both school-based case identification and educational initiatives occurred in elementary schools and, as a consequence, the majority of individuals impacted by these interventions were in the 5–14-year age range.

As part of a multifaceted approach, physician-targeted education was provided both in small group, problem-based learning sessions, as well as in clinic-based physician peer-to-peer academic detailing interventions. Policy interventions at state and local levels targeted environmental air quality standards, smoking legislation, and children’s access to asthma medications in schools. School-based case identification for asthma within Region IV of the Chicago Public Schools was linked with appropriate medical and social service institutions in an effort to improve access to quality care.

The area of intervention, corresponding to the boundaries of Region IV of the Chicago Public School District, is depicted in Figure 1. While the intervention phase began in June 2003, the initial year of the project primarily involved case identification with few major interventions occurring until the beginning of year 2 (June 2004–July 2005).

FIGURE 1.

Zip code map of Chicago with superimposed boundaries for the CAACP Chicago site intervention area. Zip codes with predominant AA self-designated race (>90%) are in red.

The institutional review boards of all participating sites approved these interventions and the analysis of pharmacy data.

Record Selection

Asthma medication dispensing data were obtained as a limited dataset from a national retail pharmacy chain for the years 2004–2006. Data from years prior to 2004 were not available. As multiple diverse interventions influencing both patients/families and health care providers were implemented in this project, there is no single metric that will quantify what percentage of the intervention occurred prior to 2004. It is estimated, however, that only 10–20% of the intervention were implemented during this first project year (reporting period of September 2003–June 2004).

This pharmacy chain had an approximately 50% share of the retail pharmacy market in the Chicago area.10 Of participants in the case management portion of the CAACP intervention surveyed regarding their pharmacy of choice, 59% reported using this pharmacy chain to fill their prescriptions.

Inclusion criteria for this analysis included (1) resident of Chicago (zip code of residence 606xx), (2) aged 5–9 or 10–17 (corresponding to the age groups used in the National Committee on Quality Assurance’s Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set [HEDIS] criteria), and (3) four or more dispensings during a calendar year for any of the following asthma medications: short-acting beta-agonists (SABA), long-acting beta-agonists, inhaled anticholinergics, ICS, cromones, methylxanthines, leukotriene inhibitors, and combination products that include any of these medications. This medication list is similar to that used by the HEDIS quality improvement measure for appropriate asthma care.11 In instances where multiple inhalers were dispensed on a single day, each inhaler was counted as a separate dispensing. If a controller and a reliever medication were dispensed simultaneously, they would be counted as one dispensing in each category. The project was unable to link diagnosis codes with dispensing records. Consequently, because oral prednisone is used to treat chronic medical conditions other than asthma, it was not included as a qualifying medication.

Demographic information from the pharmacy database was restricted to year of birth, gender, zip code of residence, payer for the medication (i.e., Medicaid, self-pay, other third-party insurance), and the medication-dispensing date. Ecologic data1 from the US 2000 census were used because the pharmacy database lacked information about race and socioeconomic status. These ecologic data included the percentage of families within a zip code living below the poverty line and the predominant racial composition of the zip code of residence. Predominant racial composition was defined as one race comprising more than 90% of a zip code’s population.

Analysis was restricted to people with persistent asthma as defined by the third inclusion criterion above (having four or more dispensings of any asthma-specific medication in a calendar year). Appropriate asthma medication use was defined in two ways. The first measure was that used by HEDIS, which defines appropriate medication use as having at least one of the four filled prescriptions for a controller medication. The second measure was a modification of the HEDIS asthma measure and emphasized consistent use of ICS, thereby applying a stricter criterion to define appropriate asthma medication use. Keeping the same denominator used by HEDIS (having four or more dispensings of any asthma-specific medication in a calendar year), the modified measure required people filling four or more prescriptions for SABAs (suggesting poor control) to also fill four or more prescriptions for ICS in order to be scored as using medications appropriately. Those individuals with fewer than four fills for SABAs would be considered as having appropriate asthma medication use regardless of the number of ICS prescription. ICS was selected as the controller of choice in this stricter definition of appropriate asthma medication use because national guidelines available at the time of the project clearly defined this medication class (ICS) as the drugs of choice for patients with moderate or severe persistent asthma.2 This modified quality measurement was chosen as the primary outcome, but data were also analyzed using the standard HEDIS criterion as a secondary outcome.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics used medians with inter-quartile range for age, percentages for gender and self-pay status, proportions for living in primarily African American zip codes, and proportions of families living below the poverty line in participants’ zip codes of residence. Logistic regression was used to calculate the odds ratio for appropriate ICS use, by year, for patients in each age group (5–9 and 10–17, corresponding to the age categories used by HEDIS) in the CAACP Chicago intervention area (reference = all other Chicago zip codes not included in intervention area), adjusting for a zip code’s predominant racial composition, percentage of families living below the poverty line in each zip code, gender, and Medicaid (>50% of a subject’s medications paid for by Medicaid) or self-pay (>50% of a subject’s medications paid for by the patient) status.

Subjects could not be compared across all 3 years because the coded identifier linking them to their prescriptions changed each year. The logistic regression model was run independently for each year (rather than assessing the effect over time) to avoid biases resulting from correlation between observations across years.

A two-tailed p value of less than 0.05 defined statistical significance for all outcomes. Analyses were performed using STATA/SE 10.0 for Windows (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

A total of 22,861 5–17-year-old Chicago residents were identified in the pharmacy database (Table 1). Approximately 60% of the identified residents were male, and 55–70% of residents used Medicaid as a payer for the majority of their medications with less than 1% paying for the majority of their prescriptions out-of-pocket. Approximately one in four residents identified in the study lived in a predominantly African American zip code. According to 2000 census data, the self-reported racial composition of the intervention area as a whole was 35% African American, 34% Caucasian, and 24% other. Self-reported ethnicity in the intervention area was 43% Hispanic. Within the intervention area, approximately one quarter of residents lived below the poverty line; in the non-intervention area, approximately one in six residents lived below the poverty line.

Table 1.

Demographic description of subjects aged 5–17 filling prescriptions for at least four asthma medications

| Ages 5–9 years | Ages 10–17 years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | |

| Number | ||||||

| Study-wide | 3,371 | 3,526 | 4,307 | 3,821 | 3,731 | 4,105 |

| Intervention area | 765 | 769 | 951 | 723 | 722 | 805 |

| Non-intervention area | 2,606 | 2,757 | 3,356 | 3,098 | 3,009 | 3,300 |

| Age, years (median, [IQR]) | ||||||

| Study-wide | 7(6–8) | 7(6–8) | 7(6–8) | 13(11–15) | 13(11–15) | 13(11–15) |

| Intervention area | 7(6–8) | 7(6–8) | 7(6–8) | 13(11–15) | 13(11–15) | 13(11–15) |

| Non-intervention area | 7(6–8) | 7(6–8) | 7(6–8) | 13(11–15) | 13(11–15) | 13(11–15) |

| Sex (% male) | ||||||

| Study-wide | 59.1 | 58.3 | 59 | 55.9 | 57 | 58.1 |

| Intervention area | 58.6 | 56.2 | 59.2 | 57.1 | 59.4 | 58.5 |

| Non-intervention area | 59.2 | 59 | 58.4 | 55.7 | 56.4 | 57.9 |

| Medicaid (% receiving) | ||||||

| Study-wide | 57.7 | 62.1 | 68.7 | 55.2 | 60.1 | 68.3 |

| Intervention area | 62.4 | 65.6 | 72.5 | 60.1 | 66.5 | 76.6 |

| Non-intervention area | 56.3 | 61.2 | 67.7 | 54.1 | 58.6 | 66.2 |

| Self-pay (% using) | ||||||

| Study-wide | 0.89 | 0.74 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 0.64 | 0.78 |

| Intervention area | 1.69 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 1.24 | 0.0 | 0.37 |

| Non-intervention area | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.89 |

| Predominant AA zip (% living in) | ||||||

| Study-wide | 24.9 | 24.1 | 23.6 | 26.2 | 26.4 | 26.7 |

| Intervention area | 6.7 | 5.1 | 06.7 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 7.3 |

| Non-intervention area | 30.2 | 29.3 | 28.3 | 31 | 31.3 | 31.4 |

| Percent of families in zip below poverty line | ||||||

| Study-wide | 17.8 | 17.6 | 17.5 | 17.8 | 17.9 | 18 |

| Intervention area | 23.4 | 22.9 | 23.1 | 23.5 | 23.4 | 23.6 |

| Non-intervention area | 16.2 | 16.1 | 15.9 | 16.4 | 16.5 | 16.6 |

IQR inter-quartile range, AA African American

The majority of identified subjects received adequate quality of care as judged by ICS medication prescription fill patterns, regardless of the definition measure used (Tables 2 and 3). The percentage of quality care was slightly higher in the intervention area than in the non-intervention area, particularly for the modified HEDIS criterion (Table 2).

Table 2.

Appropriate use of asthma medications as defined by modified HEDIS criterion by age group and year (odds ratio ± 95% CI adjusted for individual characteristics)

| Ages 5–9 years | Ages 10–17 years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | |

| Percent of participants with quality care | ||||||

| Unadjusted (residence in intervention area) | 1.13 (0.95, 1.35) | 1.12 (0.95, 1.32) | 1.18(1.01, 1.38)* | 1.12 (0.94, 1.33) | 1.08 (0.92, 1.27) | 1.07 (0.91, 1.26) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | ||||||

| Residence in intervention area | 1.18 (0.96, 1.45) | 1.26 (1.04, 1.53)* | 1.30 (1.08, 1.55)* | 1.19 (0.99, 1.44) | 1.18 (0.99, 1.42) | 1.10 (0.91, 1.32) |

| Self-pay | 0.40 (0.19, 0.83)* | 0.27 (0.12, 0.59)* | 0.25 (0.13, 0.50)* | 0.64 (0.33, 1.24) | 0.54 (0.24, 1.22) | 0.45 (0.22, 0.92)* |

| Medicaid | 0.98 (0.84, 1.15) | 0.63 (0.54, 0.73)* | 0.58 (0.50, 0.68)* | 0.91 (0.80, 1.05) | 0.90 (0.79, 1.04) | 0.99 (0.85. 1.15) |

| Residence in predominant African American zip code | 0.74 (0.61, 0.90)* | 0.82 (0.68, 0.98)* | 0.82 (0.69, 0.97)* | 0.97 (0.82, 1.14) | 0.87 (0.73, 1.02) | 0.83 (0.71, 0.98)* |

| Percent of families below poverty line in residence zip code | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99)* | 0.98 (0.97, 0.98)* | 0.98 (0.98, 0.99)* | 0.99 (0.98, 1.00)* | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99)* | 0.99 (0.98, 1.00)* |

| Male | 0.92 (0.79, 1.07) | 1.00 (0.87, 1.15) | 0.97 (0.85, 1.10) | 0.98 (0.86, 1.12) | 0.94 (0.83, 1.08) | 0.97 (0.85, 1.10) |

HEDIS Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set, CI confidence interval

*p < 0.05

Table 3.

Appropriate use of asthma medications as defined by HEDIS criterion by age group and year (percent, and odds ratio ± 95% CI adjusted for individual characteristics)

| Ages 5–9 years | Ages 10–17 years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | |

| Percent of participants with quality care | ||||||

| Unadjusted (residence in intervention area) | 1.14 (0.86, 1.51) | 1.13 (0.9, 1.43) | 1.21 (0.95, 1.52) | 0.93 (0.74, 1.18) | 1.02 (0.82, 1.26) | 1.23 (0.96, 1.59) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||||||

| Residence in intervention area | 1.17 (0.85, 1.62) | 1.28 (0.98, 1.67) | 1.26 (0.95, 1.6) | 0.93 (0.71, 1.22) | 1.04 (0.81, 1.32) | 1.03 (0.77, 1.37) |

| Self-pay | 0.26 (0.11, 0.57)* | 0.27 (0.12, 0.64)* | 0.18 (0.09, 0.38)* | 0.27 (0.14, 0.55)* | 0.28 (0.12, 0.65)* | 0.34 (0.16, 0.74)* |

| Medicaid | 1.16 (0.91, 1.46) | 0.67 (0.54, 0.82)* | 0.75 (0.59, 0.91)* | 1.21 (0.99, 1.47) | 1.17 (0.98, 1.40) | 1.44 (1.16, 1.78) |

| Residence in predominant African American zip code | 0.71 (0.54, 0.95)* | 0.89 (0.70, 1.13) | 0.71 (0.56, 0.91)* | 0.80 (0.63, 1.01) | 0.83 (0.67, 1.03) | 0.62 (0.49, 0.79)* |

| Percent below poverty line in residence zip code | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99)* | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00)* | 0.99 (0.98, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.00)* | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) |

| Male | 0.87 (0.69, 1.10) | 1.02 (0.84, 1.24) | 0.97 (0.80, 1.19) | 1.13 (0.93, 1.36) | 0.87 (0.73, 1.03) | 0.96 (0.79, 1.17) |

HEDIS Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set, CI confidence interval

*p < 0.05

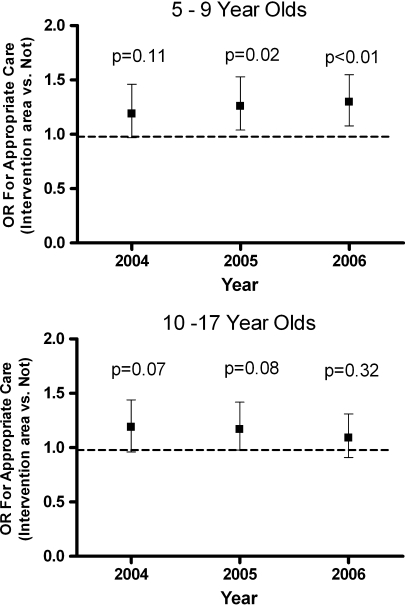

In separate multivariate logistic regression models run for each year of the analysis, in the 5–9 age group, residence in the intervention area was associated with a significantly increased odds ratio for appropriate use of ICS using the modified HEDIS criterion (Table 2 and Figure 2). There was no significant difference using the standard HEDIS criterion between children of either age group living in the intervention area and those living in control zip codes (Table 3). Self-pay status was significantly associated with decreased odds of appropriate ICS use in children aged 5–9 using the modified HEDIS criterion. This association was present for both age groups using the standard HEDIS measure. Medicaid as the primary payer for medications had a variable association with the odds ratio for appropriate care across age groups and definitions. There was also a small but statistically significant effect of percent of families living below poverty in 5–9-year-olds for 2005 and 2006, using the HEDIS measure, and for all years in this age group, using the modified HEDIS measure. Residence in a predominantly African American zip code had an association with a decreased odds ratio of appropriate asthma medication, although this did not reach statistical significance in all years (Tables 2 and 3). Gender did not contribute significantly to the odds ratio of quality asthma care.

FIGURE 2.

Adjusted odds ratio for appropriate care (residence in intervention area vs. other zip code of residence, using modified HEDIS criterion). (For appropriate care, subjects with ≥4 asthma medication dispensings/year must have at least one dispensing of a controller medication; additionally, subjects with >4 dispensings for short-acting beta-agonist medication must have at least four dispensings for inhaled corticosteroids.) Ages 5–9 years (top) and 10–17 years (bottom), Chicago, 2004–2006. Bars represent 95% confidence interval of odds ratio. Dashed line represents odds ratio of 1. p values represent statistical significance for odds ratio for appropriate care for each individual year for residence in intervention area vs. other zip code.

Discussion

This paper presents a methodology for assessing the effect of large multi-component community interventions for asthma, using administrative pharmacy data for asthma medication dispensings. The results suggest a beneficial effect on the quality of asthma care in the subgroup of children with asthma targeted by the project. This methodology has potential for evaluating medication use in the management of other diseases that are amenable to large-scale, community-wide interventions.

The primary outcome of the study, using a modified HEDIS measure, was the significant association between living in the intervention area and appropriate asthma care for children aged 5–9. The absence of this effect when using the less rigorous standard HEDIS measure was expected because the project focused on the improvement of long-term asthma control and, thus, compliance with consistent use of ICS. A trend toward improved quality measures in the adolescent age group did not reach clinical significance. This finding may be due the Chicago CAACP’s targeting of younger age groups, i.e., 6–12-year-olds attending elementary and middle school with only partial overlap in the 10–17-year-old age group.

Although there was slight improvement in quality of asthma care, using the standard HEDIS measurement, the overall quality of asthma therapy, as measured by the modified HEDIS criterion of prescription dispensings of asthma medications, declined slightly over the 3 years of this analysis, with greater declines in the non-intervention group. This overall trend was unexpected, given previous reports of improvement in appropriate asthma medication use.1

The number of persons with medication dispensings in both the intervention and non-intervention areas increased over the 3 years, with the most substantial increase occurring in 2006. This increase paralleled an increase in the percentage of patients using Medicaid to pay for the majority of their medications. Illinois expanded the eligibility level for entry into its KidCare program (funded by the State Children’s Health Insurance Program) in 2003, and in July 2006, AllKids (a program designed to provide insurance for children whose parents’ income disqualified them for traditional Medicaid) was implemented in Illinois, further increasing state-funded health care for uninsured children.13 The expansion of KidCare and the creation of AllKids may explain the increase in the percentage of children covered by Medicaid. This increased enrollment of children who were previously uninsured and therefore less likely to have received asthma education during office visits may explain the declining odds ratio for appropriate ICS use in the Medicaid population.

The methodology described had several strengths. Most notably, it allowed for ready assessment of a large-scale, multi-component intervention on a population level. The technique had adequate power to discern a modest effect with odds ratios of 1.23 to 1.28. Further, the methodology was of modest cost in that it used an existing database of de-identified data.

This method of evaluation had several important limitations. The method cannot prove a causal link between the Chicago CAACP and the observed improvements in medication dispensing patterns. While CAACP was the largest program operating in the intervention area from 2004 to 2006, other small concurrent programs, or factors not measured in the analysis, may have contributed to the effect. Including additional years of baseline dispensing data prior to the CAACP would have reduced this concern. Conversely, interventions occurring in the rest of the city would bias the analysis towards the null hypothesis.

Spatial resolution is a further limitation of the study. Due to HIPAA privacy concerns, patient location was available only at the zip code level. While the zip code areas had substantial overlap with the intervention area, portions of some of the zip codes included in the analysis were outside of the intervention boundaries. The lack of specific addresses also precluded the use of more appropriate cluster analyses.14

The lack of diagnosis codes meant there was no certainty that the recipients actually had a diagnosis of asthma. The selection criterion of four or more asthma medications, however, should have effectively decreased contamination by other diseases. For example, a young child with an upper respiratory infection and wheezing might have filled one prescription for a SABA but would not have appeared in the program cohort.15 Exclusion of prednisone as an index medication also probably limited dataset contamination by other conditions treated with oral steroids.

Another limitation is that the data were obtained from a single pharmacy chain within Chicago. However, this pharmacy’s market share is approximately 50% in the Chicago area and probably higher in the inner city. Excluding data from other pharmacies might have resulted in an undercount of patients qualifying for the selection criteria. Further, pharmacy data from the county hospital system were not included, potentially missing a significant number of uninsured patients and possibly contributing to the small number of self-pay patients in the cohort.

The exclusion of mail-order prescriptions in this analysis was also problematic because patients who ordered their controller medications from mail-order pharmacies but obtained their reliever medications from a local pharmacy would have been incorrectly identified as receiving poor quality of care. A further systematic bias might have been the characteristics of patients who filled their medications through mail-order pharmacies. These patients are likely to be more stable and well controlled. Removing them from the pool of individuals filling their prescriptions at local pharmacies would theoretically increase the number of more poorly controlled subjects in the remaining population.

Finally, a number of subjects might have received free medications from a number of sources, such as the mobile care van that services school children in the catchment area. In addition, most physician practices give samples to patients receiving new or different-strength medications, resulting in an undercounting of those medications. As with the mail-order pharmacies, there was no direct way to adjust for this effect or determine whether this effect created a bias toward ICS or beta-agonists.

Evaluating the impact of multi-component asthma intervention programs on a population level remains challenging. There are numerous limitations to the use of administrative pharmacy data as a means of monitoring appropriate medication use. When interpreted in the context of other supportive findings, however, this method can advance the evaluation of large-scale programs and may be applicable to other disease-control programs.

Acknowledgement

This project was supported through a cooperative agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services, under program announcement 03030.

Conflict of interest The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

From the US Census Bureau (ArcGIS version 10; ESRI; Redlands, CA, USA).

References

- 1.Naureckas ET, Thomas S. Are we closing the disparities gap? Small-area analysis of asthma in Chicago. Chest. 2007;132(5 Suppl):858S–865S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Persky V, Turyk M, Piorkowski J, Coover L, Knight J, Wagner C, et al. Inner-city asthma: the role of the community. Chest. 2007;132(5 Suppl):831S–839S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pont LG, Werf GT, Denig P, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Identifying general practice patients diagnosed with asthma and their exacerbation episodes from prescribing data. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;57(11):819–825. doi: 10.1007/s00228-001-0395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moth G, Vedsted P, Schiotz PO. Identification of asthmatic children using prescription data and diagnosis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(6):605–611. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krigsman K, Nilsson JLG, Ring L. Refill adherence for patients with asthma and COPD: comparison of a pharmacy record database with manually collected repeat prescriptions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(4):441–448. doi: 10.1002/pds.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naureckas ET, Dukic V, Bao X, Rathouz P. Short-acting beta-agonist prescription fills as a marker for asthma morbidity. Chest. 2005;128(2):602–608. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.2.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schatz M, Zeigler RS, Vollmer WM, Mosen D, Mendoza G, Apter AJ, et al. The controller-to-total asthma medication ratio is associated with patient-centered as well as utilization outcomes. Chest. 2006;130(1):43–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horner SD. Using the Open Airways curriculum to improve self-care for third grade children with asthma. J Sch Health. 1998;68(8):329–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1998.tb00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruzzese JM, Markman LB, Appel D, Webber M. An evaluation of Open Airways for Schools: using college students as instructors. J Asthma. 2001;38(4):337–342. doi: 10.1081/JAS-100000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.“Edging out the competition.” Drug Store News 2002 March 25. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m3374/is_4_24/ai_84237951. Accessed June 27, 2008.

- 11.Turk A. Overview of HEDIS 2000 asthma measurement. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6:S342–S346. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert panel report 2: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1997. Publication No. 97-4051.

- 13.Illinois Government News Network (2007, May 26). Gov. Blagojevich applauds U.S. Congress for addressing SCHIP shortfall; Illinois to receive an estimated $181 million in additional federal SCHIP dollars.http://wwwc.illinois.gov/PressReleases/ShowPressRelease.cfm?SubjectID=1&RecNum=5999. Accessed June 27, 2008.

- 14.Donner A. An empirical study of cluster randomization. Int J Epidemiol. 1982;11(3):283–286. doi: 10.1093/ije/11.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oesch JM, Kim H, Kieckhefer GM, Greek AA, Baydar N. Does your child have asthma? Filled prescriptions and household reporting of child asthma. J Pediatr Health Care. 2006;20:374–383. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]