Abstract

Motivation: Identification of genomic regions of interest in ChIP-seq data, commonly referred to as peak-calling, aims to find the locations of transcription factor binding sites, modified histones or nucleosomes. The BayesPeak algorithm was developed to model the data structure using Bayesian statistical techniques and was shown to be a reliable method, but did not have a full-genome implementation.

Results: In this note we present BayesPeak, an R package for genome-wide peak-calling that provides a flexible implementation of the BayesPeak algorithm and is compatible with downstream BioConductor packages. The BayesPeak package introduces a new method for summarizing posterior probability output, along with methods for handling overfitting and support for parallel processing. We briefly compare the package with other common peak-callers.

Availability: Available as part of BioConductor version 2.6. URL: http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/BayesPeak.html

Contact: jonathan.cairns@cancer.org.uk

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Chromatin ImmunoPrecipitation (ChIP) experiments produce short DNA fragments, preferentially selected to identify the locations of protein binding sites, histone modifications or nucleosome positions. In the ChIP-seq protocol, as described in Robertson et al. (2007), the 5′-end of one strand of each fragment is sequenced, obtaining a ‘read’, and then aligned to a reference genome. These aligned reads form ‘peaks’—localized regions of high read density—along the genome. Determining the locations and magnitudes of these peaks is an active area of research, and a number of tools exist for the so-called ‘peak-calling’, using a variety of methodologies.

The algorithm described in Spyrou et al. (2009) takes a Bayesian approach to modelling aligned reads from ChIP-seq data. Many peak-callers model read counts with the Poisson distribution, and thus do not allow for the overdispersion seen in practice. BayesPeak addresses this issue by using the negative binomial distribution.

The method optionally allows for the inclusion of a control sample, which enables us to mitigate the effect of experimental artefacts where protein binding is absent. Additionally, the algorithm was shown (in Spyrou et al., 2009) to call merged peaks that are narrower than regions identified by other callers and this, along with inference from posterior probabilities, can improve the efficiency of downstream processing, e.g. motif analysis.

We present the R package BayesPeak, which uses a modified version of the algorithm in Spyrou et al. (2009) with a flexible genome-wide implementation. As well as providing compatibility with common input formats and downstream analyses, the BayesPeak package adds additional methods for summarizing data, tools for handling overfitting and support for parallel processing.

2 METHODS

The BayesPeak package, written in R and C, forms part of the BioConductor release branch since version 2.6 (Gentleman et al., 2004).

The implementation of BayesPeak allows it to take advantage of parallel processing, improving its efficiency. We provide optional parallelization support using the multicore package (Urbanek, 2009) for Linux/Mac OS X.

BayesPeak can analyse a human genome in under 12 h, when run in parallel on an 8-core 2.5 GHz machine. For a benchmark example in which the treatment and control .bed files totalled 33 million reads (2.3 GB of disk space), BayesPeak required not more than 3 GB of RAM (although larger .bed files require more RAM). R version 2.11.0 or later is required.

The BayesPeak software package fits a hidden Markov model (HMM) to the data (aligned reads) as follows: the genome is divided into ‘jobs’, i.e. short regions on which the algorithm is run independently. By default, jobs are of length 6 Mb (numerical stability may be compromised in larger jobs), and each job region is expanded by 2 Kb in each direction (to allow peaks falling on the boundary between two jobs to be called).

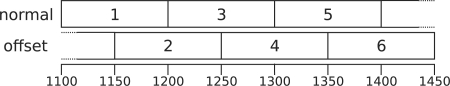

Within a job, the region is divided into small bins (each of length 100 bases, by default), and reads are aggregated by the bin in which they start and the strand on which they lie. A two-state HMM is fitted to these aggregate counts. The HMM's hidden states correspond to enrichment or unenrichment for sites of interest. A hidden state produces two negative binomial emissions, each corresponding to a bin count (one on each strand), with enriched states tending to emit larger values. The HMM is fitted through MCMC techniques that sample from the posterior distributions of the parameters. The analysis is performed a second time on the same job region, but with all bins offset by half their width (the ‘offset’ analysis) as illustrated in Figure 1. Further details can be found in Spyrou et al. (2009).

Fig. 1.

A schematic representation of a hypothetical peak region, with bins labelled by genomic order. Supposing that each bin has an associated PP value above a threshold (by default 0.5), we would merge these six bins into a peak from 1100 to 1450, with an associated PP value as calculated in Section 2.1.

The output of each job is the posterior probability (PP) of each site being enriched. The data are summarized to form the final peaks as follows. All bins with PP values greater than a user-specified threshold (by default, 0.5) are collected. Where two adjacent jobs call the exact same bin, the maximal PP value is used—this is a rare occurrence under default settings.

2.1 Merging bins

Bins from both the ‘normal’ and ‘offset’ jobs that are adjacent or overlap are merged to form contiguous peak regions.

The PP value of the peak can be calculated from the constituent bins by either naively taking the maximal value, or by using the ‘lower bound’ method defined as follows: assign the indices 1,…, n to the n bins within the peak, in order of genomic location (as in Fig. 1). Note that bins with adjacent indices overlap. Now let the PP value of bin i be πi, and define qi = 1 − πi as the probability of no enrichment in bin i.

Let Sn be the set of all subsequences of {1,…, n} such that I ∈ Sn ⇔ I contains no consecutive integers ⇔ the bins with indices in I do not overlap. Then, for each I ∈ Sn, a lower bound for the probability of enrichment in at least one of the original n bins is  .

.

The ‘best’ (highest) lower bound for the probability of peak enrichment is therefore the maximum of this quantity,

We can find Q(n) by dynamic programming since, by conditioning on whether i ∈ I, we have Q(i) = min(Q(i − 1), qiQ(i − 2)).

The advantage of using this method over taking the maximum PP value is that it can give an appropriate score to sustained regions of only moderately large PP values, which will be undervalued when taking the maximum.

We tested BayesPeak on the NRSF/REST ChIP-seq dataset from (Johnson et al., 2007), in which a small subset of regions have been experimentally validated, and we compared the findings against other common peak callers.

3 RESULTS

We present the peak-caller comparison results in the Supplementary Material. BayesPeak demonstrated a competitive sensitivity and specificity on the genome-wide scale and showed a substantial overlap with other peak-callers. The over-fitting correction greatly improved the enrichment for true binding sites in BayesPeak's data, as did subsequent filtering by PP value.

In its raw output, BayesPeak returns PP values for each bin and, for each job, the posterior mean of each estimated parameter (excluding half of the draws as burn-in). As of BayesPeak version 1.1.3, MCMC samples of several key parameters are also present, permitting convergence tests such as the Geweke diagnostic in the boa (Smith, 2007) or coda (Plummer et al., 2010) packages.

Since the summarized output is in RangedData format, this allows direct analysis of the peaks in any downstream package compatible with IRanges (Pages et al., 2010), including those in BioConductor. For example, ChIPpeakAnno (Zhu et al., 2010) can annotate the output.

We have observed some phenomena that occur with lower quality data. For example, over-fitting can occur as follows: the model assumes that for each job there are both enriched and unenriched states. As such, when there are no peaks in a job or when the peaks are extremely weak, these two states are used to explain the natural variance present in the unenriched background. We identify over-fit jobs from their low λ1 values (where λ1 is the expected number of counts in an enriched bin), and from their PP values being spread out over [0, 1] rather than tending to be 0 or 1. BayesPeak supports the identification and removal of jobs that have encountered this effect (Supplementary Table S2 and Fig. S1).

4 DISCUSSION

BayesPeak provides a Bayesian analysis, with advantages including allowance for overdispersion in read counts and a competitive genome-wide specificity and sensitivity. By anticipating peak structure, BayesPeak does not call peaks based on sheer numbers of reads without appropriate read formation.

Careful selection of job regions may improve the analysis. For example, we can use prior knowledge to partition jobs in a manner that avoids analysing the centromeres and telomeres, which usually contain no reads. This will prevent unnecessary computation, and may also improve results in the surrounding regions.

There is scope for adapting the BayesPeak approach to other forms of peak-calling. For example, some histone mark data consist of regions of enrichment containing many peaks and, in BrDU-seq data, peaks are much broader than those in transcription factor data.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are grateful to Dr Jason Carroll's group and Dr Duncan Odom's group for access to test datasets, and to Dr Mark Dunning for beta testing.

Funding: J.C. is funded by a Medical Research Council grant. We acknowledge the support of the University of Cambridge, Cancer Research UK, and Hutchison-Whampoa.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Gentleman RC, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DS, et al. Genome-wide mapping of in vivo protein-DNA interactions. Science. 2007;316:1497–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.1141319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pages H, et al. IRanges: Infrastructure for Manipulating Intervals on Sequences. 2010 R package version 1.6.6. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer M, et al. Coda: Output Analysis and Diagnostics for MCMC. 2010 R package version 0.13-5. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson G, et al. Genome-wide profiles of STAT1 DNA association using chromatin immunoprecipitation and massively parallel sequencing. Nature Methods. 2007;4:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BJ. boa: An R Package for MCMC output convergence assessment and posterior inference. J. Stat. Softw. 2007;21:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Spyrou C, et al. BayesPeak: Bayesian analysis of ChIP-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:299. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek S. Multicore - parallel processing in R on machines with multiple cores or CPUs version 0.1-4. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Zhu LJ, et al. ChIPpeakAnno: a bioconductor package to annotate ChIP-seq and ChIP-chip data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:237. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.