Abstract

Background/Aims

To evaluate associations between delayed gastric emptying (GE) assessed by the octanoic acid breath test and upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms.

Methods

A historical, prospective study included 111 consecutive symptomatic adults referred for a GE breath test because of upper abdominal symptoms suggestive of delayed GE. Exclusion criteria included underlying organic disease associated with delayed GE. Patients completed a symptom questionnaire and underwent a GE octanoic breath test. Patients with delayed GE were compared with those with normal results, for upper GI symptoms.

Results

Early satiety was the only symptom significantly associated with delayed GE. It was observed in 52% of subjects with delayed GE compared to 33% patients with no evidence of delayed GE (P = 0.005). This association was seen for all degrees of severity of delayed GE. Patients with early satiety had a t1/2 of 153.9 ± 84.6 minutes compared to 110.9 ± 47.6 minutes in subjects without it (P = 0.002). In a logistic regression model, early satiety was significantly associated with delayed GE (OR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.01-5.18; P = 0.048).

Conclusions

Early satiety is the only patient-reported GI symptom associated with delayed GE. The utility of GE tests as a clinical diagnostic tool in the work-up of dyspeptic symptoms may be overrated.

Keywords: Breath tests, Dyspepsia, Gastric emptying

Introduction

Delayed gastric emptying (GE) is associated with a wide spectrum of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, in particular post prandial fullness/early satiety, nausea and vomiting.1 Although several studies have reported an association between delayed gastric emptying and clinical symtoms,2,3 others have not found support for this association.4,5 A recent study in patients with delayed GE did not find an association between GE and GI symptoms, except for symptoms that were associated with proximal stomach dysfunction.6 It is noteworthy that rapid GE may also result in nausea, bloating and epigastric fullness, making the clinical dignosis of delayed gastric emptying problematic.7

Thus, symptoms of delayed GE are nonspecific and may overlap with other GI disorders including functional dyspepsia, peptic ulcer disease or gastric malignancy.8 Moreover, in some prokinetic drug trials, there has been a poor correlation between medical facilitation of GE and symptom improvement, suggesting that delayed GE was not the cause of the symptoms. In addition, no dose dependent effect was seen, ie, between increasing severity of GE delay and symptom severity.9,10

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the clinical manifestation of delayed GE, including antral hypomotility, impaired gastric accommodation,11 visceral hypersensitivity, absence of the interstitial cells of Cajal12 and gastric dysrhythmias. These putative mechanisms are controversial, because a moderate delay of GE in healthy individuals is not associated with an increase in meal-related symptoms.13

Ghoos et al14 were the first to show the benefit of measuring the GE rate of solids by a non-invasive octanoic acid breath test. Although GE scintigraphy of a solid-phase meal is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of delayed GE,15 the octanoic acid breath test provides reproducible results that correlate with GE scintigraphy.14,16,17 The primary aim of the present study was to further characterize associations between upper GI symptoms and delayed GE as assessed by patient reports of symptoms and results of the octanoic acid breath test. An additional objective was to look at possible associations between the severity of GE delay (classified as mild, moderate and severe) and upper GI symptoms.

Materials and Methods

The E. Wolfson Medical center serves as a secondary and tertiary referral center. This study was approved by the hospital's institutional review board. Each patient gave written informed consent.

This was a historical, prospective study of 111 consecutive adults, aged 18 to 79 years, who were referred for a GE breath test because of upper abdominal symptoms suggestive of delayed GE. Only patients fullfilling the Rome II criteria for functional dyspepsia and failed empirical medical therapy were included. Patients were excluded at entry if they had a peptic ulcer, an organic disease associated with delayed GE such as diabetes mellitus, Parkinson's disease, cerebrovascular accident, neuromuscular disease, eating disorder, gastrostomy tube, gastric outlet obstruction, history of gastric surgery, fundoplication or treatment with anticholinergic or antidepressants drugs.

Endoscopic criteria for exclusion were esophagitis of over grade 2 by Savary-Miller classification or all types of Los Angeles classification. Patients with diaphragmatic hernia of larger than 3 cm or erosive gastritis were excluded. Medical treatment was prescribed for all patients with pathologic findings and the GE tests were conducted between 2 weeks to 3 months after cessation of treatment only in those patients who did not respond to medical therapy.

As detailed below, the study participants completed a sociodemographic and symptom questionnaire and underwent a GE breath test. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) status was determined by endoscopic biopsy (CUTest, Temmler Pharma, Marburg, Germany) or urea breath test.

The questionnaire included socio-demographic data, a review of medical history, and the section of the official Rome II questionnaire on upper GI symptoms, with particular emphasis on relation to nausea and vomiting, post-prandial fullness, early satiety and bloating. Only patients with frequent symptoms of at least 25% of time were included in the study.

Gastric Emptying Breath Tests

GE was evaluated using the previously validated 13C-labelled octanoic acid 4 hour breath test (BreathID, Exalenz, Jerusalem, Israel).17 All breath tests were performed in the morning, over a 4-hour period in a sitting position after an overnight fast. Proton pump inhibitors were discontinued at least 1 week prior to evaluation of GE.

The BreathID collected breath samples continuously from patients who were connected to the instrument through a nasal canula based circuit. The instrument analyzed breath samples before and after 13C enriched octanoic acid administration. The BreathID system utilized 100 mg 13C-labelled octanoic acid dissolved in a standard sized scrambled egg with 2 slices of bread, which provide 250 kcal, as the test meal. Based on Molecular Correlation Spectrometry, the BreathID continuously measured 13CO2 and 12CO2 concentrations from the patient's breath and established the 13CO2/12CO2 ratio, which was displayed vs time on the screen. The 13CO2/12CO2 ratio was normalized for patient's weight, height and 13C substrate and dose. This provided percentage dose recovery and cumulative percentage dose recovery and calculated the t1/2, tlag and the gastric emptying coefficient (GEC, data not presented in this article). These calculations were based on analyses using a non-linear model, as described by Ghoos et al.14 The results have been printed on a thermal printer and saved to a hard disk.

Based on Ghoos et al,14 the normal ranges for the GE parameters were defined as t1/2 50-94 minutes, tlag 12-52 minutes and GEC 2.95-3.55 (delayed emptying < 2.95). Based on the t1/2 values and as we could not find any severity index in assessment of delayed GE time in the literature, we divided our patients into 4 groups: normal emptying, 50-94 minutes; mild delay, 95-199 minutes (up to 2 times of upper normal limit); moderate delay, 200-299 minutes (up to 3 times of upper normal limit); and severe delay, ≥ 300 minutes (over 3 times of upper normal limit).

In order to evalute the association between GI symtoms and delayed GE, patients with delayed GE were compared to a group without delayed GE and a dose effect was sought for individual symptoms.

Statistical Methods

Data were analyzed using the SPSS 9.0 statistical analysis software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). For continuous variables descriptive statistics were calculated and were reported as mean ± SD. Normality of distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (cut-off at P = 0.01). All continuous variables had approximately normal distributions permitting the use of parametric methods. The t test for independent samples was used to compare continuous variables between subjects with and without delayed GE. One way analysis of variance was used to compare continuous variables across breath test categories. Pearson's correlation coefficient was calculated to describe associations between continuous variables.

Categorical variables are presented as frequency (%). The χ2 test (exact test when indicated) was used to assess associations between delayed GE and symptoms, gender and breath test categories. All tests were 2-sided and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

The study population was comprised of 111 consecutive patients referred for a GE breath test because of upper abdominal dyspeptic symptoms suggestive of delayed GE. There were 76 females (mean age 42 ± 16 years) and 35 males (mean age 43 ± 16 years). According to the Rome II criteria for functional dyspepsia, there were 36 patients with ulcer like dyspepsia, 63 with dysmotility like dyspepsia and 13 with unspecified dyspepsia.

Gastric Emptying Tests

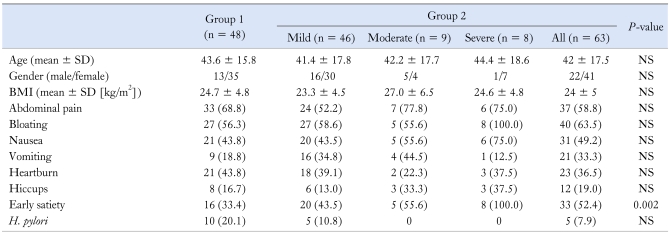

The results of the GE breath tests showed that 48 patients had no evidence of delayed GE (Group 1), while 63 (Group 2) had evidence for it. There was no difference between the groups in terms of age or body mass index (Table 1). Looking at the data from all patients (Groups 1 and 2), epigastric bloating was reported by 67 patients (60.4%), post-prandial nausea or vomiting by 60 (54.1%) and early satiety by 49 (44.1%). A significant, positive correlation was observed between the number of symptoms and the t1/2 result (r = 0.217, P = 0.026) in Group 2 with the delayed GE. However, there was no significant association between GE and symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bloating, heartburn and hiccups. There was also no significant association between these symptoms and the severity of delayed GE. The only symptom that was significantly associated with delayed GE was early satiety, which was reported by 33% in Group 1 and 52% in Group 2 (P = 0.005) (Table 1). The mean t1/2 was 153.9 ± 84.6 minutes in subjects with early satiety vs 110.9 ± 47.6 minutes in subjects without it (P = 0.002). In a logistic regression model, early satiety was significantly associated with delayed GE (OR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.01-5.18; P = 0.048). Early satiety increases the odds of mild degree of delayed GE by a factor of 2.5 (OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.1-5.6; P = 0.024) and of moderate to severe degree of delayed GE by a factor of more than 6 (OR, 6.2; 95% CI, 1.6-23.7; P = 0.003). All subjects with severe degree of delayed GE had early satiety (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.04-1.33; P = 0.003). There was no significant correlation between early satiety and tlag and GEC.

Table 1.

Comparison of the Age, Gender, Body Mass Index, Clinical Symptoms and Helicobacter pylori Status Between Group 1 and 2

H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori.

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise stated.

Helicobacter pylori and Delayed Gastric Emptying

There was no significant association between delayed GE and H. pylori status. Of 80 patients who were tested for H. pylori by urea breath test or by CUTest, 15 were positive, 10 (21%) in Group 1 and 5 (11%) in Group 2 (Table 1).

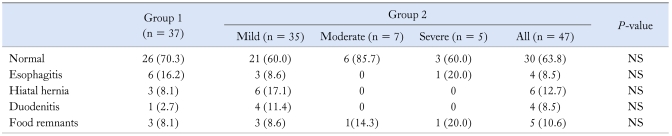

Endoscopic Findings and t1/2, tlag or Gastric Emptying Coefficient

Eighty-four patients underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy prior the GE test. The distribution of endoscopic findings are presented in Table 2. None of the endoscopic findings was associated with t1/2, tlag or GEC.

Table 2.

Comparison of the Endoscopic Findings Between the Control and Delayed Gastric Emptying Group

Group 1, control group; Group 2, delayed gastric emptying group.

Some patients had more than 1 finding. None of the differences was statistically significant. Data are presented as n (%).

Discussion

Delayed GE has been associated with various GI symptoms. An evaluation of GE is often performed when no other rational explanation is found for persistent symptoms. Identifying the presence of delayed GE may enable physicians to establish a final diagnosis in patients with vexing symptoms and no other clear explanation.18

The results of this study indicate that the majority of GI symptoms leading to the performance of a GE test are not associated with delayed GE. Early satiety was the only symptom that was found to have a significant association with delayed GE. The association with early satiety was demonstrated in mild, moderate and severe degree of GE delay. Early satiety increases the odds of mild degree of delayed GE by a factor of 2.5 and of moderate to severe degree of delayed GE by a factor of more than 6. All subjects with severe degree of delayed GE had early satiety (OR, 1.2). There was no association between early satiety and the other 2 measured parameters of GE, tlag or GEC. Our results confirmed the previous findings of Stanghellini and Sarnelli.2,3,19 However, they also found an association between delayed GE and nausea and vomiting, which was not seen in the present study. Sarnelli et al2 reported a significant association between delayed solid or liquid GE and postprandial fullness and vomiting. Vomiting is a non-specific symptom that may be induced by other etiologies such as regurgitation associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease or rumination.20,21 The prevalence of delayed GE among gastroesophageal reflux disease patients ranges from 10%-41%.21,22 Delayed GE may be a proxy for other disorders that lead to vomiting and early satiety. Karamanolis et al6 recently demonstrated that many of the symptoms previously associated with delayed GE are actually due to fundic dysmotility.

Another factor that may have impact on delayed GE is H. pylori. This hypothesis is based on theoretical grounds as well as epidemiologic and clinical studies.23 H. pylori has been found to be inversely correlated with the prevalence of delayed GE and certain studies have shown improvement of GE with eradication.24 We failed to demonstrate an association between H. pylori status and delayed GE and confirmed the previous reports of no association between delayed GE and H. pylori.25,26 Moreover, since the prevalence of H. pylori in our country is high, we would expect to see an aggravation of delayed GE symptoms if there actually is an association between them.

The major drawback of this study is the arbitrary setting of severity of GE delay to 3 groups of mild (up to twice normal GE time), moderate (up to 3 times normal GE time) and severe (over 3 times normal GE time). This setting is due to the fact that there is no valid data from the literature we could rely on. Future research is essential in grading the severity of delayed GE and comparison with symptom frequency and severity.

In conclusion, we found that among all the patient with reported symptoms, early satiety was the only symptom that was associated with delayed GE regardless of its severity. These findings suggest that the utility of GE tests as a clinical diagnostic tool in the work-up of upper GI symptoms suggestive of delayed GE may be overrated.

Footnotes

Financial support: None.

Conflicts of interest: None.

References

- 1.Soykan I, Sivri B, Sarosiek I, Kiernan B, McCallum RW. Demography, clinical characteristics, psychological and abuse profiles, treatment, and long-term follow-up of patients with gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2398–2404. doi: 10.1023/a:1026665728213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarnelli G, Caenepeel P, Geypens B, Janssens J, Tack J. Symptoms associated with impaired gastric emptying of solids and liquids in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:783–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanghellini V, Tosetti C, Paternico A, et al. Risk indicators of delayed gastric emptying of solids in patients with functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1036–1042. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8612991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott AM, Kellow JE, Shuter B, et al. Intragastric distribution and gastric emptying of solids and liquids in functional dyspepsia. Lack of influence of symptom subgroups and H. pylori-associated gastritis. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:2247–2254. doi: 10.1007/BF01299904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talley NJ, Shuter B, McCrudden G, Jones M, Hoschl R, Piper DW. Lack of association between gastric emptying of solids and symptoms in nonulcer dyspepsia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:625–630. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198912000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karamanolis G, Caenepeel P, Arts J, Tack J. Determinants of symptom pattern in idiopathic severely delayed gastric emptying: Gastric emptying rate or proximal stomach dysfunction? Gut. 2007;56:29–36. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.089508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M, Cremonini F, Ferber I, Stephens D, Burton DD. Contributions of gastric volumes and gastric emptying to meal size and postmeal symptoms in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1685–1694. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maes BD, Ghoos YF, Hiele MI, Rutgeerts PJ. Gastric emptying rate of solids in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:1158–1162. doi: 10.1023/a:1018881419010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones KL, Russo A, Stevens JE, Wishart JM, Berry MK, Horowitz M. Predictors of delayed gastric emptying in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1264–1269. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.7.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keshavarzian A, Iber FL, Vaeth J. Gastric emptying in patients with insulin-requiring diabetes mellitus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kindt S, Tack J. Impaired gastric accommodation and its role in dyspepsia. Gut. 2006;55:1685–1691. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.085365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forster J, Damjanov I, Lin Z, Sarosiek I, Wetzel P, McCallum RW. Absence of the interstitial cells of Cajal in patients with gastroparesis and correlation with clinical findings. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tack J, Coulie B, Verbeke K, Janssens J. Influence of delaying gastric emptying on meal-related symptoms in healthy subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1045–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghoos YF, Maes BD, Geypens BJ, et al. Measurement of gastric emptying rate of solids by means of a carbon-labeled octanoic acid breath test. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1640–1647. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90640-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horowitz M, Fraser RJ. Gastroparesis: diagnosis and management. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1995;213:7–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bromer MQ, Kantor SB, Wagner DA, Knight LC, Maurer AH, Parkman HP. Simultaneous measurement of gastric emptying with a simple muffin meal using [13C]octanoate breath test and scintigraphy in normal subjects and patients with dyspeptic symptoms. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1657–1663. doi: 10.1023/a:1015856211261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickman R, Steinmetz A, Bernnstine H, Groshar D, Niv Y. A novel continuous breath test versus scintigraphy for gastric emptying rate measurement. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:22–25. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181dadb23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1592–1622. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cassilly DW, Wang YR, Friedenberg FK, Nelson DB, Maurer AH, Parkman HP. Symptoms of gastroparesis: use of the gastroparesis cardinal symptom index in symptomatic patients referred for gastric emptying scintigraphy. Digestion. 2008;78:144–151. doi: 10.1159/000175836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Brien MD, Bruce BK, Camilleri M. The rumination syndrome: Clinical features rather than manometric diagnosis. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1024–1029. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCallum RW, Berkowitz DM, Lerner E. Gastric emptying in patients with gastroesophageal reflux. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:285–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keshavarzian A, Bushnell DL, Sontag S, Yegelwel EJ, Smid K. Gastric emptying in patients with severe reflux esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:738–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fock KM, Khoo TK, Chia KS, Sim CS. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric emptying of indigestible solids in patients with dysmotility-like dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:676–680. doi: 10.3109/00365529708996517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyaji H, Azuma T, Ito S, et al. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy on gastric antral myoelectrical activity and gastric emptying in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1473–1480. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caballero-Plasencia AM, Muros-Navarro MC, Martin-Ruiz JL, et al. Dyspeptic symptoms and gastric emptying of solids in patients with functional dyspepsia. Role of Helicobacter pylori infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:745–751. doi: 10.3109/00365529509096322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang CS, Chen GH, Kao CH, Wang SJ, Peng SN, Huang CK. The effect of Helicobacter pylori infection on gastric emptying of digestible and indigestible solids in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:474–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]