Abstract

Pathogenic viruses have developed a molecular defense arsenal for their survival by counteracting the host anti-viral system known as RNA interference (RNAi). Cellular RNAi, in addition to regulating gene expression through microRNAs, also serves as a barrier against invasive foreign nucleic acids. RNAi is conserved across the biological species, including plants, animals and invertebrates. Viruses in turn, have evolved mechanisms that can counteract this anti-viral defense of the host. Recent studies of mammalian viruses exhibiting RNA silencing suppressor (RSS) activity have further advanced our understanding of RNAi in terms of host-virus interactions. Viral proteins and non-coding viral RNAs can inhibit the RNAi (miRNA/siRNA) pathway through different mechanisms. Mammalian viruses having dsRNA-binding regions and GW/WG motifs appear to have a high chance of conferring RSS activity. Although, RSSs of plant and invertebrate viruses have been well characterized, mammalian viral RSSs still need in-depth investigations to present the concrete evidences supporting their RNAi ablation characteristics. The information presented in this review together with any perspective research should help to predict and identify the RSS activity-endowed new viral proteins that could be the potential targets for designing novel anti-viral therapeutics.

Keywords: miRNA, ds-RNA binding protein, Dicer, Argonaute, RISC, GW/WG motif, HIV-1 Tat, Influenza A virus NS1

Introduction

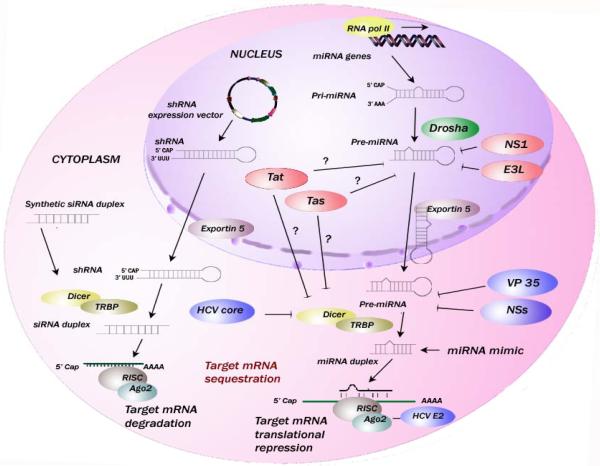

Small RNA mediated gene regulation or post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) was first discovered in plants and is now known to be functional in fungi, invertebrates as well as higher animals (Fire et al., 1991; Ecker and Davis, 1986). PTGS is a basic mechanism that regulates the level of gene expression through small RNAs that are complementary to the target mRNA sequence of a particular gene (Ecker and Davis, 1986). Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are exogenously supplied synthetic RNAi mediators; however, endogenous cellular microRNAs (miRNAs) too can cause viral mRNA sequestration/degradation through RNAi pathway. Endogenous RNAi works through miRNAs that are encoded by the cellular miRNA genes (Lee et al., 1993). miRNA is transcribed as a highly structured primary miRNA which is processed in the nucleus by the type III RNase, Drosha, into ~ 70 nucleotide long stem-loop precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA). Pre-miRNA is exported out of the nucleus via exportin-5 and diced into 19–24 nucleotide long mature miRNA by another type III RNase, Dicer, in the cytoplasm (Fig 1). One of the two miRNA strands called `guide strand' is loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), a multi-protein complex consisting of RNA processing/degrading enzymes Argonautes along with Dicer and its cofactor HIV-1 TAR RNA binding protein (TRBP) and several other proteins (Fig 1). Dicer is also capable of processing RNAs derived from RNA viruses, transposons or synthetic short hairpin RNA (shRNA) to yield small siRNAs that can be loaded into the RISC. In essence, RNAi is a multistep process that ultimately leads to target mRNA degradation or translational repression, depending on the degree of complementarity between the si/miRNA and the target mRNA (Hutvágner and Zamore, 2002; Zeng et al., 2003; Zeng and Cullen, 2003; Kanwar et al 2010).

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of RSS activity of different viral proteins that inhibit the host RNAi pathway.

Following transcription from miRNA genes in the nucleus, pri-miRNAs are processed to pre-miRNAs by Drosha. Exportin-5 facilitates the export of pre-miRNA into the cytoplasm where they are processed by Dicer/TRPB into mature miRNA. Dicer also processes the shRNAs transcribed from shRNA expression vectors into siRNA. The mature miRNA/siRNA guide strands are loaded on to RNA induced silencing complex (RISC). RISC targets the complementary mRNA transcripts. Viral RSS proteins inhibit the cellular RNAi pathway at different steps. Viral proteins NS1 of influenza virus and E3L of Vaccinia virus possess RNA binding domains, localize to the nucleus and suppress RNAi by sequestering the small RNA intermediates. HIV-1 Tat / PFV-1 Tas localize to the nucleus and possess RSS activity by interaction with the cytoplasmic Dicer protein. Tat and Tas may also act by sequestration of small RNAs similar to other viral proteins in the nucleus (shown as ?). Viral proteins NSs of LACV and VP35 of Ebola virus localize in the cytoplasm, possess RNA binding domains and suppress RNAi by sequestering the small RNA intermediates. HCV core and E2 proteins interact with Dicer and Ago2 proteins, respectively, in RISC to suppress RNAi.

A cluster of human miRNAs consisting of miR-28, miR-125b, miR-150, miR-223 and miR-382 collectively targets 3' un-translated region (3' UTR) whereas miRNA-29a targets the Nef region of human immunodeficiency virus -1 (HIV-1) mRNAs, resulting in the suppression of HIV viral gene expression (Huang et al., 2007; Ahluwalia et al., 2008; Pierre Corbeau, 2008). Similarly, human miR-199a and miR-32 restrict Hepatitis C virus (HCV) and primate foamy virus type 1 (PFV-1) replication respectively (Murakami et al., 2009; Lecellier et al., 2005), whereas miR-100 and miR-101 function against human cytomegalovirus (Wang et al., 2008). Studies have demonstrated that deliberate repression of mammalian dicer, an enzyme involved in the processing of microRNAs, enhances the replication of HIV-1 (Triboulet et al., 2007), vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) (Otsuka et al., 2007) and influenza A virus (Matskevich and Moelling, 2007), and provides indirect evidence supporting the RNAi phenomenon

Cellular RNAi machinery can also utilize virus derived dsRNA to produce small RNAs capable of inducing RNAi against the virus. For instance, HIV-1 TAR element is shown to act as a substrate for the RNAi machinery leading to production of miRNAs capable of targeting viral transcripts (Ouellet et al., 2008).

Based on significant amounts of literature supporting cellular RNAi system's ability to launch attack against the viral pathogens, it can be concluded that RNAi pathway, indeed, acts as an antiviral defense system enabling host cell to restrict the viral replication at the post-transcriptional level. Interestingly, some viruses have evolved mechanisms to counter-attack this antiviral defense system by encoding proteins or RNA molecules functioning as RNA silencing suppressors (RSS), to inhibit different stages and components of RNAi pathway and enable successful viral replication (Table-1).

Table 1.

RSS activity of different viral proteins/RNAs

| Viral Protein/RNA | Amino acids/nucleotide length | Mechanism of action for RSS activity | Subcellular localization | Domain important for RSS | IFN/PKR antagonism | RSS Host specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 Tat | 100–112 | Dicer binding (Bennasser and Jeang, 2006; Qian et al., 2009) | Nucleus (Endo et al., 1989; Chauhan et al., 2003; 2007a; 2007b) | Basic/RNA binding (Qian et al., 2009) | Yes/No (Gallo, 1999) | Mammals |

|

| ||||||

| Influenza NS1 | 237 | siRNA binding (de Vries et al., 2008) | Nucleus, Cytoplasm (Brask et al., 2005; Melen et al., 2007; Newby et al., 2007) | RNA binding (Delgadillo et al.,2004; Bucher et al., 2004) | Yes/Yes (Guo et al., 2007; Bergmann et al.,2000) | Plants, insects, mammals |

|

| ||||||

| HCV core | 191 | Dicer binding (Wang et al., 2006) | Cytoplasm (Barba et al., 1997) | RNA binding (wang et al., 2006) | Yes/No (Bode et al.,2003; Lin et al., 2006) | Mammals |

| Envelope E2 | 148 | Ago2 binding (Ji et al., 2008) | Cytoplasm (Duvet et al., 1998, Kien et al,2003) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Ebola VP35 | 340 | siRNA binding (Hasnoot et al.,2007) | Cytoplasm (Bjoörndal et al.,2003) | RNA binding (Hasnoot et al.,2007) | Yes/Yes (Cardenas et al.,2006; Hartman et al., 2004) | Mammals |

|

| ||||||

| Vaccinia E3L | 190 | siRNA binding (Li et al.,2003) | Nucleus (Yuwen et al., 1993) | RNA binding (Li et al.,2003) | Yes/Yes (Chang et al., 1992; Langland and Jacobs, 2004) | Insects |

|

| ||||||

| PFV-1 Tas | 308 | Dicer binding? | Nucleus (Bannert et al., 2004) | (?) | (?) | Mammals |

|

| ||||||

| LACV NSs | 92 | siRNA binding (Soldan et al, 2004) | (?) | (?) | Yes/No (Blakqori et al.,2007) | Mammals |

|

| ||||||

| Adenovirus VA1 dsRNA | ~ 160bp | Dicer/Exprt 5 (Andersson et al., 2005) | Nucleus/cytoplasm | NA | Yes/Yes (Kitajewski et al.,1986a, Kitajewski et al., 1986b) | Mammals |

NA=not applicable

Viral RNA silencing suppressors: Viral proteins/RNAs counteract RNA interference

RNA silencing suppression phenomenon was first discovered in plant viruses. The plants infected with potato virus and cucumber mosaic virus exhibited suppression of trans-gene silencing (Brigeti et al., 1998). Subsequently, the list for such trans-gene silencing entities has extended to include many plant (Alvarado and Scholthof, 2009) as well as animal viruses. The human viruses with RSS activity (Table-1) include HIV, Influenza A virus, HCV, Vaccinia, Ebola virus, Foamy viruses including primate foamy virus-1 (PFV-1), and arbovirus La Crosse virus (LACV).

a. HIV-1 Tat protein as RSS

HIV-1 transactivator of transcription (Tat) protein is fundamental to virus gene expression in the host cell. It regulates viral gene expression by promoting the elongation phase of HIV-1 transcription via binding to a trans-activation response (TAR) element in HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) sequence that acts as a viral promoter. By binding to the TAR element, Tat engages RNA polymerase and other components of transcription machinery, and phosphorylates C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II by CDK9, making it stable for transcription elongation (Karn, 1999). Tat protein is fundamental for virus replication in host cells. The importance of Tat in the viral life cycle is now augmented as Tat also aids the virus evade the host's innate defense mechanism generated by the RNAi pathway. Further, miRNA mediated gene silencing is suppressed during HIV-1 infection in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Triboulet et al., 2007). Investigations by Bennasser and coworkers revealed the RNA silencing suppressor activity of Tat, which can ablate the RNAi-mediated suppression of viral replication by interacting with and inhibiting a crucial enzyme, Dicer, involved in the maturation of miRNA as well as siRNA (Fig 1, 2 and Table-1; Bennasser and Jeang, 2006; Qian et al., 2009).

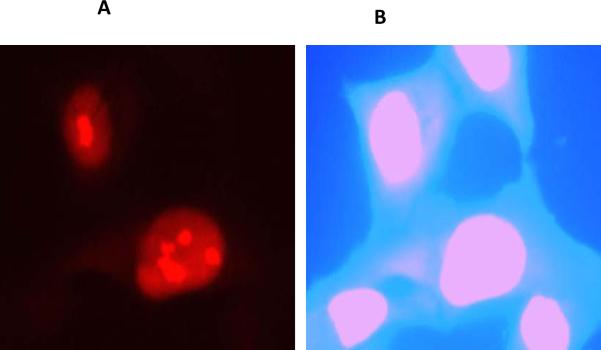

Fig 2. HIV Tat expression.

pcDNA-Tat plasmid transfection in SVGA (astrocytes) cells followed by immunostaining after 48h using Tat monoclonal antibody. (A) Tat expression was seen in the nucleus. (B) Hoechst nuclear staining of panel A.

Interestingly, interaction between HIV-1 Tat and Dicer enzyme is shown to be dependent on the presence of RNA, as RNase treatment inhibits this interaction. The helicase domain of Dicer and the lysine 51 (K51) residue of HIV-1 Tat are essential for the interaction (Bennasser and Jeang, 2006). Further studies using different Tat peptides have demonstrated that this interaction does not involve N-terminal transactivation domain of Tat and that the basic domain of Tat was apparently required for the RSS activity (Qian et al., 2009). In mammalian cells, Tat has been reported to block the mi/siRNA processing step performed by Dicer (Bennasser et al., 2006); however, in the plant system, it is suggested that Tat inhibits the RNAi pathway by sequestering the mature and functional siRNA molecules (Qian et al., 2009). The RSS activity of Tat protein has been questioned in an experimental system where 86 amino acid or 101 amino acid long Tat protein was unable to rescue the suppression of reporter gene expression by RNAi (Lin and Cullen, 2007).

More precisely, Tat is a nuclear protein which specifically localizes to the nucleus and nucleolus (Fig1, Table-1; Endo et al., 1989; Chauhan et al., 2003; 2007a; 2007b). Dicer is involved in the processing of miRNA and siRNA from their precursor forms to produce the functional forms (Fig 1). The processing by Dicer occurs in the cell cytoplasm. It is, however, intriguing to understand how Tat (with two nuclear localization signals) interacts with a cytoplasmic protein Dicer to inhibit its function. One possibility is that the Tat is involved in this interaction immediately after its synthesis in the cytoplasm and before being imported into the nucleus. Alternatively, Dicer could also be functional in the nucleus for the processing of si/miRNA intermediate forms.

In addition to the direct inhibition of Dicer function, HIV-1 RNA can act as a precursor for the generation of si-/mi- RNA-like decoys, such as TAR RNA. These decoys bind and sequester TRBP, which is an essential co-factor of Dicer, thus, making the latter unavailable for si/miRNA processing during RNAi pathway (Gatignol et al., 1991; Bennasser et al., 2006). Further, HIV-1 can also surmount the base-pair complementarity dependence of RNAi due to its high mutation rate (Westerhout et al., 2005).

In addition to its role in transcriptional elongation, Tat promotes HIV-1 replication in infected cells by antagonizing the effects of the interferon (IFN) pathway. In vitro studies have shown that Tat could inhibit IFN mediated nitric oxide synthase activity, which is essential, otherwise, to containment of pathogens by macrophages (Barton et al., 1996). Tat has also been reported to induce the expression of the suppressor of cytokine signaling–2 (SOCS-2), which directly inhibits STAT1. STAT1 is the effector transcription factor downstream of IFN gamma. Thus, Tat inhibits IFN induced gene expression through SOCS-2 (Cheng et al., 2009). On the contrary, Tat has been documented to induce over-expression of IFN-α in the macrophages, leading to cell proliferation arrest and immune-suppression (Gallo, 1999). Thus, Tat plays a major role in HIV-1 host defense evasion. However, further in depth studies are required to delineate the exact underlying mechanism of Tat RSS activity.

b. Human Influenza A virus NS1 protein as RSS

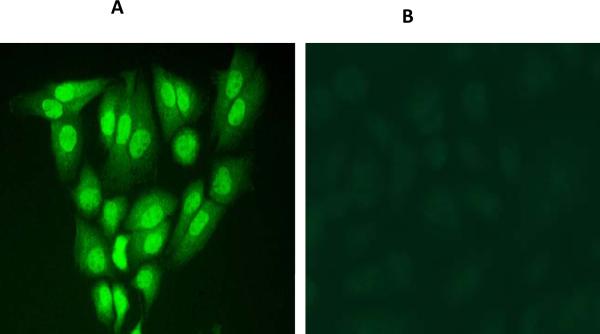

NS1 protein of human Influenza A virus is a non-structural protein possessing an RNA binding domain which enables it to interact with a variety of RNA species (Hatada and Fukuda, 1992; Hatada et al., 1992; Liu et al., 1997; Hatada et al., 1997). Amino acid residues R38 and K41 in the N terminal domain are important for RNA binding (Wang et al., 1999). NS1 acts as a virulence factor for influenza virus by enhancing viral gene expression and ablating cellular antiviral defenses. NS1 specifically promotes translation initiation of viral mRNAs by the polyribosomes over non-viral mRNAs in the transfected cells (de la Luna et al., 1995). It promotes the nuclear export of viral mRNA while retarding the export of cellular pre-mRNAs by inhibiting the poly(A) synthesis machinery that specifically processes cellular pre-mRNAs. (Chen and Krug, 2000). The RSS activity of NS1 protein is demonstrated by its ability to rescue the shRNA-mediated silencing of luciferase expression in human HEK-293T cells (de Vries et al., 2008). NS1 from different strains of influenza virus show different degree of RNAi suppression. NS1 protein from the highly pathogenic A/WSN/33 strain is found to be the most potent suppressor of shRNA mediated RNAi. In experiments on HIV-1 with mutation in RSS region of Tat gene, NS1 protein WAS able to complement the HIV-1 Tat function (de Vries et al., 2008). Interestingly, like HIV-1 Tat protein, NS1 is reported to exert RSS activity in the plant system by sequestration of small RNAs (Delgadillo et al., 2004; Bucher et al., 2004). In mammalian systems, NS1 could act through similar mechanism of small RNA sequestration to suppress RNAi. NS1 is a nuclear protein (Fig 1, 3 and Table 1), that has also been shown to localize in the cytoplasm (Brask et al., 2005; Melen et al., 2007; Newby et al., 2007). The nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of NS1 would allow it to bind and trap small siRNA precursors as well as mature forms in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Coincidently, similar to Tat protein, RSS activity of NS1 has been questioned in the mammalian system with contradictory results when tested with different reporter gene expression systems (Kok et al., 2006). To corroborate the RSS activity of NS1, more investigations on the mammalian systems are needed.

Fig 3. Influenza A virus NS1 expression.

pcDNA-NS1 plasmid transfection in N1E (neuroblastoma) cells followed by immunostaining after 48h using polyclonal NS1 antibody. (A) NS1 expression was seen in the nucleus. (B) Negative control with isotype antibody.

In addition to RSS activity, NS1 can boost the viral replication by nullifying type I IFN responses by inhibiting the cytoplasmic dsRNA sensor RIG1 (Guo et al., 2007), as well as Protein Kinase R (PKR) mediated inhibition of protein synthesis (Bergmann et al., 2000; reviewed in Hale et al., 2008).

c. HCV core and envelope (E2) proteins as RSS

RNAi pathway functions as a host restriction factor during HCV infection. Similar to HIV and Influenza virus, HCV also harbors RNAi suppressor activity. The HCV core protein is a structural protein that forms component of the viral nucleocapsid (Giannini and Brechot, 2003). In addition to the packaging of viral RNA during the viral life cycle, core protein is also involved in enhancing pathogenicity of HCV via RSS. HCV core protein is reported to curtail RNAi mediated suppression of reporter gene expression in Hela cells. It could rescue gene expression from RNAi by virtue of its ability to interact with Dicer. Dicer, a component of RNAi pathway, has been suggested to be a limiting factor for HCV replication (Wang et al., 2006). HCV RNA intermediates and IRES (internal ribosomal entry sites) RNA act as substrates for Dicer and induce anti-HCV RNAi (Wang et al., 2006). Predominant cytoplasmic localization of HCV core protein increases the probability of its interactions with Dicer, which itself in the cytoplasm is involved in the maturation of si/miRNAs (Fig 1, Table; Barba et al., 1997; Yasui et al., 1998). The N-terminal 62 amino acids region of the core protein by virtue of its interaction with Dicer exhibits the RSS activity (Wang et al., 2006). The hydrophilic N-terminal domain of core protein is characterized by patches of basic amino acids and serves as a putative nuclear localization signal (NLS) (Suzuki et al., 1995), and these basic amino acids are involved in binding with RNA and ribosomes (Santolini et al., 1994). In the case of HIV-1 Tat, interaction with Dicer is dependent on the presence of RNA in the complex (Bennasser et al., 2006). There appears to be a strong possibility that HCV core protein might also need small RNA as a bridge to form a complex with Dicer. Further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

HCV envelope protein E2 also shows RSS activity. E2 protein has the ability to interact with the argonaute 2 (Ago 2) protein involved in the RNAi pathway, rendering it non-functional. In the cytoplasm, Ago2 forms the effector complex called RISC along with Dicer, TRBP and the mature siRNA or miRNA. The RISC then sequesters the target mRNA, leading to silencing of its expression. This inhibition of Ago2 by E2 protein is concentration dependent (Ji et al., 2008). However, structural basis of this interaction and the domain of the E2 that is important for its RSS activity remain under-investigated. E2 protein is localized in the cytoplasm of infected cells specifically in the endoplasmic reticulum, which is the budding site for new HCV particles (Table 1; Duvet et al., 1998, Kien et al, 2003), whereas Ago2 is found in distinct foci called P bodies in the cytoplasm where mRNA is either stored or degraded (Sen and Blau, 2005; Liu et al., 2005). It will be interesting to determine at what stage of its synthesis does the E2 protein escape into the cytoplasm and interact with Ago2.

HCV core and E2 proteins inhibit the antiviral RNAi launched by the host cell and thereby promotes viral replication. In addition to RSS activity, core protein can also surmount the IFN mediated antiviral defense raised by the host cell through inhibition of transcription factors like STAT1 (Bode et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2006). Hence, HCV core and E2 proteins act as viral arsenals to protect the virus against host defense system. An understanding of these protein interactions would lead to the development of better anti-viral therapeutics.

d. Ebola virus VP35 protein as RSS

Ebola virus, a member of the Filoviridae family, is known to cause viral hemorrhagic fever in humans. Ebola virus has a single stranded, negative sense RNA as its genome. Its nonstructural protein VP35 is involved in the packaging of the viral RNA in the newly formed virus particles (Johnson et al., 2006 a, 2006b). VP35 acts as a suppressor of RNAi in the mammalian cells (Fig 1), thus promoting viral infection. VP35 was found to complement Tat deficient HIV-1 replication (recombinant HIV-1 in which viral transcription is competent but Tat RSS activity is insufficient) indicating that it could rescue viral gene expression from RNAi similar to Tat (Hasnoot et al., 2007). VP35 possesses a dsRNA binding domain important for its function in packaging of viral RNA. This dsRNA binding domain is essential for the RSS activity of VP35 protein as evidenced by the use of substitution and deletion mutants (Hasnoot et al., 2007). The ability of this domain to bind to a variety of dsRNA species presents a strong possibility that VP35 RSS activity functions through sequestration of small RNAs involved in RNAi.

The dsRNA binding domain of VP35, which bears an amino acid sequence similar to that of RNA binding domain of Influenza NS1 protein, enhances viral replication in multiple ways. This domain has been reported to be involved in the suppression of type I IFN (Hartman et al., 2004). VP35 with intact dsRNA binding domain targets and inhibits RNA helicase and RIG-1 mediated activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), which is required to further upregulate IFN expression (Cardenas et al., 2006). VP35 is localized in the cytoplasmic inclusion bodies of the infected cells (Table-1; Björndal et al., 2003). Cytoplasmic localization of VP35 favors the possibility that it could sequester small RNAs and thus prevent them from being loaded onto RISC. Sequestration of dsRNA molecules could be the underlying mechanism in both RNAi suppression as well as IFN antagonism exhibited by VP35; however, more studies are needed to confirm this.

e. Vaccinia virus E3L protein as RSS

Vaccinia virus is a DNA virus that belongs to the Poxvirus family. Vaccinia virus E3L protein is a virulence factor that stalls many of the cellular innate antiviral responses, ensuring productive virus replication. The full-length E3L protein consists of 190 amino acids characterized by a highly conserved dsRNA binding domain (Chang and Jacobs, 1993; St. Johnston et al., 1992).

E3L protein has the ability to suppress the host cell RNAi that acts against the virus. E3L has been reported to act as a RSS (Table-1; Fig 1). It exhibits its suppression of RNA silencing-based antiviral response (RSAR) by binding to RNAi mediators through its dsRNA binding domain (Li et al., 2003). The requirement of dsRNA binding domain points toward the possibility that the underlying mechanism of inhibition of RNAi by E3L is the sequestration of dsRNA. However, none of the studies on mammalian cells have shown E3L protein-mediated suppression of siRNA- and shRNA-dependent RNAi (Lantermann et al., 2007). This could be because of the differences in the basic components of the RNAi machinery in insect and mammalian systems. E3L protein is localized in the nucleus of the infected cell which makes it difficult to predict how and at what step in RNAi pathway E3L exhibits its RSS activity (Fig 1, Table-1; Yuwen et al., 1993).

The E3L protein exhibits antagonistic effect on dsRNA-, ssRNA- or dsDNA-mediated activation of interferon beta (Marq et al., 2009). E3L protein also promotes the viral infection by sequestrating dsRNA involved in the activation of cellular PKR signaling and eIF2α phosphorylation during antiviral response (Chang et al., 1992; Langland and Jacobs, 2004).

f. Primate foamy virus Tas protein as RSS

Primate foamy virus (PFV) is a retrovirus, closely related to HIV-1. PFV causes zoonotic infections in humans (Linial, 2000). RNAi pathway has been shown to be active against PFV-I in human cells. Human miRNA-32 robustly curtails the replication of PFV-1 in human cells (Lecellier et al., 2005). However, PFV-1, like its close relative HIV-1, encodes a protein that ablates the effect of RNAi. Tas protein, primarily localized in the nucleus (Fig 1, Table-1), acts as a transactivator of viral transcription by interacting with p300 and p300/CBP associated factor PCAF, and results in histone acetylation (Bannert et al., 2004). PFV-1 Tas, similar to HIV-1 Tat protein, suppresses the RNAi mediated viral gene silencing. In the presence of Tas protein, microRNAs are found to accumulate in mammalian cells, indicating that Tas protein mediates blockage of the RNAi effector step (Lecellier et al., 2005). Tas is localized in the nucleus and its mode of action in suppressing RNAi pathway remains to be elucidated.

In contrast, PFV-1 Tas protein does not show any direct RNAi suppressor activity in mammalian cells. PFV-1 Tas is incapable of rescuing gene expression that is knocked down by use of shRNA (Lin et al., 2007). Further studies are required to understand the exact mechanism of action of PFV-1 Tas protein and its role as a RSS.

g. La Crosse virus NSs protein as RSS

La Crosse virus (LACV) is a member of the Bunyaviridae family and causes pediatric encephalitis and aseptic meningitis in humans (McJunkin et al., 2001). LACV is a negative sense RNA virus containing a segmented genome (Cabradilla et al., 1983). The non-structural protein NSs of LACV functions as a virulence factor by curtailing various cellular defenses propelled against the virus. NSs has also been reported to exhibit the RSS activity possibly via dsRNA sequestration (Table-1); however, the mechanism of its action is yet to be elucidated (Soldan et al, 2004).

To supplement its RSS activity and strengthen viral replication, NSs also acts as a suppressor of the IFN system. It inhibits the antiviral type I IFN system in both mammalian cell cultures and in vivo mouse models in brain cells (Blakqori et al., 2007).

h. Adenovirus VA RNA as RSS

Unlike a majority of pathogenic viruses that use viral proteins to confer the RSS activity, adenovirus uses its non-coding RNA (VA) to perform the RSS activity. Adenovirus possesses a dsDNA genome encoding viral proteins, along with two non-coding RNA molecules transcribed by RNA polymerase III that fold into a characteristic stem loop structure. These non-coding RNAs enhance viral mRNA translation, promoting viral replication (Mathews and Shenk, 1991). In addition, adenoviral VA RNAs have been reported to inhibit the activation of eIF2α kinase or PKR that blocks the initiation of protein synthesis (McKenna et al., 2006).

Adenoviral VA 1 RNA is expressed in very high concentrations in the infected cells and saturates the exportin-5 protein involved in the nuclear export of mRNA transcripts and pre-miRNAs. Thus, VA 1 RNA blocks the RNAi pathway by inhibiting Dicer as is evident by the absence of mature miRNA/siRNA (Table 1). This observation is also supported by in vitro binding and functional studies (Lu and Cullen, 2004). Moreover, VA 1 RNA also acts as a competitive substrate for Dicer enzyme thus incapacitating it from processing siRNA and miRNA (Andersson et al., 2005).

VA 1 RNA also antagonizes the IFN effect by inhibiting the activation of PKR. The presence of VA 1 RNA is essential for viral replication in the presence of IFNs. Adenovirus lacking the presence of VA RNA is sensitive to IFN mediated antiviral action (Kitajewski et al., 1986a, Kitajewski et al., 1986b). Further, cells transfected with VA RNA induce type 1 IFN in cells (Weber et. al., 2006). This property of VA RNAs could be used judiciously to the advantage to arrest replication of pathogenic viruses. However, further investigations are needed to draw the inference.

Based on the literature, these viral proteins and RNA molecules showed RSS activity when tested in the reporter gene expression assays, however, it is important here to understand that the endogenous cellular RNAi pathway works mainly through the miRNAs. Thus, it is essential to study these viral proteins for their activity against the cellular miRNA pathway rather than the reporter gene silencing mediated by exogenous siRNAs. Such studies will clearly reflect on the RSS potential of these viral proteins and RNA molecules.

Criteria to predict RSS activity in viral proteins

In the following, we have provided criteria to predict viral proteins as potential RSSs based on the characteristics possessed by the described viral RSS proteins of vertebrates and plant viruses. In general, RNA binding and GW/WG motifs present in the sequences of viral proteins may predict the RSS activity and should be verified by functional assays.

(i). Viral RSS proteins harbor dsRNA binding domains

The viral proteins discussed above appear to have a similar mode of RSS activity and the majority of these viral RSSs are early phase nonstructural proteins. It is, therefore, likely that these proteins manifest similar structural and functional characteristics. We compared their amino acids sequences and found no sequence homology or characteristic sequences. However, it was noticed that majority of the RSS proteins showed the presence of dsRNA binding domain (Table 1). Further, as expected these domains contain positively charged basic amino acids. In HIV-1 Tat, an RNA binding sequence (amino acids 49–57) of RKKRRQRR is well known (Campbell and Loret, 2009). Influenza virus NS1 protein bears N-terminal RNA binding domain characterized by the presence of lysine and arginine (Wang et al., 1999). Thus, screening viral proteins for sequence domains rich in basic amino acids may be an effective search for proteins possessing RSS activity. Furthermore, amino acid substitution analysis may be effective in confirming the importance of basic amino acid sequences to assess their importance in RSS activity, and may provide better clues for developing strategies to inhibit viral replication. Nevertheless, RNA binding domain is a characteristic property of HIV-1 Tat, influenza NS1, HCV core protein, Ebola VP35, Vaccinia E3L, LACV NSs and PFV Tas protein, as discussed above.

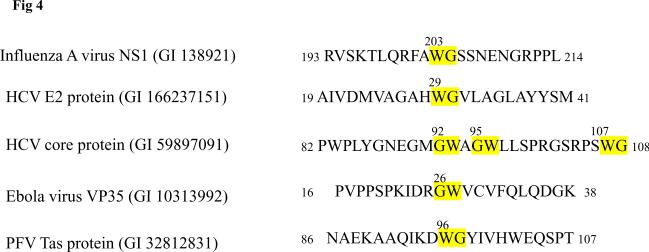

(ii). GW/WG motifs in the viral RSS proteins

RNA viruses in particular are more susceptible to the RNAi mediated host defense system and have, thus, evolved to neutralize it using, RNAi silencing suppressors. During viral RNA replication, viral dsRNAs are produced and are processed into 21–24 nucleotide dsRNAs by host enzyme Dicer. These siRNAs are assembled with Argonaute (Ago) proteins in RISC to target viral RNA for degradation. It has been reported in plant viruses that the GW/WG motifs in viral proteins plays a critical role in disabling RISC by sequestering Ago proteins. The GW/WG motifs act as Ago hooks and are essential for Ago binding. The GW/WG motifs were found to be conserved in C-terminal domains of plant viruses but are variable in the N-terminal domains as well.

El-Shami and coworkers reported GW/WG motifs in human proteins, such as DNA dependent RNA polymerase V, function as an Ago binding platform (El-Shami et al., 2007). All cellular proteins containing GW/WG repeat have a positive role in RNAi. Recently, it has been reported that the P38 capsid protein of Turnip Crinkle virus (TCV) mimics host-encoded, GW/WG-containing proteins normally required for RISC assembly/function (Azevedo J et al., 2010). P38 binds Ago1 and inhibits RNAi, thereby, helping viral replication. It would be interesting to search for this feature in mammalian viruses and to predict the viral RSS activity of unreported proteins. Recently, a genome wide computational study on GW/WG has reported several human proteins with GW/WG as conserved motifs and these observations have been further corroborated by the experiments on their binding with argonautes [Karlowski et al., 2010]. We further searched GW/WG motifs in known mammalian viral RSSs and found that a majority of them harbor this characteristic repeat (Fig 4). Employing molecular modeling (I-TASHAR server [Zhang, Y., 2008]) for HCV core protein, we found that the GW/WG motifs reside on the protein surface (Fig 5) suggesting that the motifs possibly interact with the host Ago proteins to ablate RNAi. To elucidate the significance of GW/WG motif in RSS activity, mutagenesis studies are needed to complement the observations.

Fig 4. Viral RSS proteins possess GW/WG motif.

The amino acid sequence of viral RSS proteins showing the presence of GW/WG motifs. GW/WG motif has been implicated in the interaction with Ago proteins and presence of this motif in viral RSS proteins may indicate their ability to interact with and inhibit Ago proteins involved in RNAi.

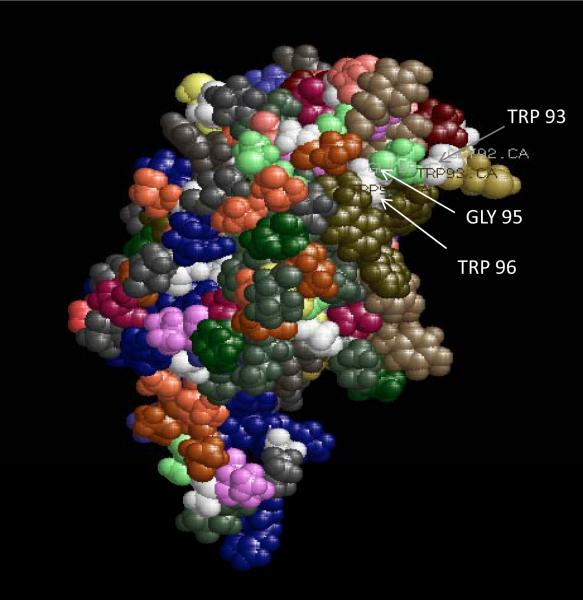

Fig 5.

Three-D molecular modeling of HCV core protein: Protein modeling was performed by using I–TASSER server. Protein modeling of HCV core protein revealed GW/WG motifs on the surface and these may be potential binding sites with Ago proteins.

Perspective

The IFN pathway is one of the first lines of antiviral innate defense mechanisms launched by the mammalian host cells. This IFN pathway can be activated by double stranded RNA molecules. siRNAs (virus derived) have been shown to activate the IFN pathway. However, RSS proteins can inhibit the components of host RNAi pathway that synthesizes siRNA or miRNA. Thus, viruses possessing such RSS proteins might indirectly show an effect on the dsRNA-mediated activation of the IFN system by suppressing the synthesis of double stranded RNA.

Viral RSSs have important implications in basic research that widely uses siRNA/miRNA based approaches to study different aspects of viral infection and pathogenesis. Viruses possessing proteins or RNAs as RSSs have the capability of masking the effect of siRNA/miRNA. This property makes it difficult to interpret and infer the results of virus-targeted RNAi mediated gene knock down experiments. Thus, prior knowledge of possible RSS activity of the viruses will help in designing experiments using appropriate controls. Towards this end, the first step would be to identify the common domain composition and the structural characteristics associated with RSS activity in known viruses.

Sequence analysis of viral RSS proteins has revealed no amino acid similarity. However, similarities in the functional domains possessing dsRNA-binding property have been demonstrated. Thus, further in depth analysis of RNA binding domains, dicer binding domains as well as other functional domains in known viral RSS proteins should give a better insight into the typical domain characteristics associated with RSS activity. The acquired information will help predict the RSS activity in other viral and host proteins with similar domain compositions. Another desirable feature for an RSS in viral proteins is the presence of GW/WG motif in the protein sequence. This motif binds Ago proteins and makes RISC incompetent in degrading the viral RNA. Presence of such motifs, in combination with other features (dsRNA binding domain), in viral proteins with unreported activity could predict the RSS. Besides, the characteristics, like, early phase expression, non-structural nature and the cytoplasmic localization property of these viral proteins would provide additional advantage in predicting the RSS activity, although the nuclear localization could also be a less common feature as seen in Tat, Tas and NS1 proteins. The significance of these RSSs is that they might attenuate the potency of molecular therapeutic interventions such as siRNA/miRNA and shRNAs in gene therapy approaches. Viral mimicry of GW/WG repeats-containing proteins, which bind with Agos, appears a global defense strategy of viruses and other pathogens to dampen the host's RNAi arsenal. Hence, deciphering the RSS activity of pathogenic viruses will strengthen the future drug/vaccine designing strategies for viral inhibition.

Conclusion

RNAi pathway intersects with the interferon (IFN) pathway, which is a primary innate anti-viral mechanism. Both of these pathways are activated by the presence of dsRNA molecules. In order to rule out the effect of the IFN pathway in RSS phenomenon in mammalian viruses, in depth mechanistic studies are needed. Viral RSS phenomenon if established, may pose a big challenge in therapeutic RNAi approaches to curtail viral infections.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Dilip Vakharia for his critical reading of the manuscript. The work was supported by NIH grant RO1 NS 050064 (AC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ahluwalia JK, Khan SZ, Soni K, Rawat P, Gupta A, Hariharan M, Scaria V, Lalwani M, Pillai B, Mitra D, Brahmachari SK. Human cellular microRNA hsa-miR-29a interferes with viral nef protein expression and HIV-1 replication. Retrovirology. 2008;5:117. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarado V, Scholthof HB. Plant responses against invasive nucleic acids: RNA silencing and its suppression by plant viral pathogens. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2009;20(9):1032–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson MG, Haasnoot PC, Xu N, Berenjian S, Berkhout B, Akusjärvi G. Suppression of RNA interference by adenovirus virus-associated RNA. J. Virol. 2005;79(15):9556–9565. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9556-9565.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azevedo J, Garcia D, Pontier D, Ohnesorge S, Yu A, Garcia S, Braun L, Bergdoll M, Hakimi MA, Lagrange T, Voinnet O. Argonaute quenching and global changes in Dicer homeostasis caused by a pathogen-encoded GW repeat protein. Genes Dev. 2010;24(9):904–915. doi: 10.1101/gad.1908710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bannert H, Muranyi W, Ogryzko VV, Nakatani Y, Flügel RM. Co-activators p300 and PCAF physically and functionally interact with the foamy viral trans-activator. BMC Mol. Biol. 2004;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barba G, Harper F, Harada T, Kohara M, Goulinet S, Matsuura Y, Eder G, Schaff Z, Chapman M, Miyamura T, Brechot C. Hepatitis C virus core protein shows a cytoplasmic localization and associates to cellular lipid storage droplets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:1200–1205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barton CH, Biggs TE, Mee TR, Mann DA. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 regulatory protein Tat inhibits interferon-induced iNos activity in a murine macrophage cell line. J. Gen. Virol. 1996;77:1643–1647. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-8-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennasser Y, Jeang KT. HIV-1 Tat interaction with Dicer: requirement for RNA. Retrovirology. 2006;3:95. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennasser Y, Yeung ML, Jeang KT. HIV-1 TAR RNA subverts RNA interference in transfected cells through sequestration of TAR RNA-binding protein, TRBP. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:27674–27678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600072200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergmann M, Garcí a-Sastre A, Carnero E, Pehamberger H, Wolff K, Palese P, Muster T. Influenza virus NS1 protein counteracts PKR-mediated inhibition of replication. J. Virol. 2000;74:6203–6206. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.6203-6206.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Björndal AS, Szekely L, Elgh F. Ebola virus infection inversely correlates with the overall expression levels of promyelocytic leukaemia (PML) protein in cultured cells. BMC Microbiol. 2003;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blakqori G, Delhaye S, Habjan M, Blair CD, Sánchez-Vargas I, Olson KE, Attarzadeh-Yazdi G, Fragkoudis R, Kohl A, Kalinke U, Weiss S, Michiels T, Staeheli P, Weber F. La Crosse bunyavirus nonstructural protein NSs serves to suppress the type I interferon system of mammalian hosts. J. Virol. 2007;81(10):4991–4999. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01933-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bode JG, Ludwig S, Ehrhardt C, Albrecht U, Erhardt A, Schaper F, Heinrich PC, Häussinger D. IFN-alpha antagonistic activity of HCV core protein involves induction of suppressor of cytokine signaling-3. FASEB J. 2003;17(3):488–490. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0664fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brask J, Chauhan A, Hill RH, Ljunggren HG, Kristensson K. Effects on synaptic activity in cultured hippocampal neurons by influenza A viral proteins. Neurovirol. 2005;11(4):395–402. doi: 10.1080/13550280500186916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bucher E, Hemmes H, de Haan P, Goldbach R, Prins M. The influenza A virus NS1 protein binds small interfering RNAs and suppresses RNA silencing in plants. J. Gen. Virol. 2004;85:983–991. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19734-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cabradilla CD, Jr., Holloway BP, Obijeski JF. Molecular cloning and sequencing of the La Crosse virus S RNA. Virology. 1983;128:463–468. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell GR, Loret EP. What does the structure-function relationship of the HIV-1 Tat protein teach us about developing an AIDS vaccine? Retrovirology. 2009;6:50. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cardenas WB, Loo YM, Gale M, Jr., Hartman AL, Kimberlin CR, Martínez-Sobrido L, Saphire EO, Basler CF. Ebola virus VP35 protein binds double-stranded RNA and inhibits alpha/beta interferon production induced by RIG-I signaling. J. Virol. 2006;80:5168–5178. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02199-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang HW, Jacobs BL. Identification of a conserved motif that is necessary for binding of the vaccinia virus E3L gene products to double-stranded RNA. Virology. 1993;194:537–547. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang HW, Watswon JC, Jacobs BL. The E3L gene of vaccinia virus encodes an inhibitor of the interferon-induced, double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:4825–4829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chauhan A, Hahn S, Gartner S, Pardo CA, Netesan SK, McArthur J, Nath A. Molecular programming of endothelin-1 in HIV-infected brain: role of Tat in up-regulation of ET-1 and its inhibition by statins. FASEB J. 2007a;21(3):777–789. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7054com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chauhan A, Tikoo A, Kapur AK, Singh M. The taming of the cell penetrating domain of the HIV Tat: myths and realities. J. Control Release. 2007b;117(2):14–8-162. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chauhan A, Turchan J, Pocernich C, Bruce-Keller A, Roth S, Butterfield DA, Major EO, Nath A. Intracellular human immunodeficiency virus Tat expression in astrocytes promotes astrocyte survival but induces potent neurotoxicity at distant sites via axonal transport. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(15):13512–13519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209381200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Z, Krug RM. Selective nuclear export of viral mRNAs in influenza-virus-infected cells Trends in Microbiology. 2000;8:376–383. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01794-7. Book review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng SM, Li JC, Lin SS, Lee DC, Liu L, Chen Z, Lau AS. HIV-1 transactivator protein induction of suppressor of cytokine signaling-2 contributes to dysregulation of IFN-gamma signaling. Blood. 2009;113(21):5192–5201. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng SM, Li JC, Lin SS, Lee DC, Liu L, Chen Z, Lau AS. HIV-1 transactivator protein induction of suppressor of cytokine signaling-2 contributes to dysregulation of IFN-gamma signaling. Blood. 2009;113(21):5192–201. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corbeau P. Interfering RNA and HIV: reciprocal interferences. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(9):1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de la Luna S, Fortes P, Beloso A, Ortin J. Influenza virus NS1 protein enhances the rate of translation initiation of viral mRNAs. J Virol. 1995;69:2427–2433. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2427-2433.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Vries W, Haasnoot J, Fouchier R, de Haan P, Berkhout B. Differential RNA silencing suppression activity of NS1 proteins from different influenza A virus strains. J. Gen. Virol. 2009;90:1916–1922. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.008284-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delgadillo MO, Sáenz P, Salvador B, García JA, Simoón- Mateo C. Human influenza virus NS1 protein enhances viral pathogenicity and acts as an RNA silencing suppressor in plants. J Gen. Virol. 2004;85:993–999. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19735-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duvet S, Cocquerel L, Pillez A, Cacan R, Verbert A, Moradpour D, Wychowski C, Dubuisson J. Hepatitis C virus glycoprotein complex localization in the endoplasmic reticulum involves a determinant for retention and not retrieval. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273(48):32088–32095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ecker JR, Davis RW. Inhibition of gene expression in plant cells by expression of antisense RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:5372–5376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.15.5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El-Shami M, Pontier D, Lahmy S, Braun L, Picart C, Vega D, Hakimi MA, Jacobsen SE, Cooke R, Lagrange T. Reiterated WG/GW motifs form functionally and evolutionarily conserved ARGONAUTE-binding platforms in RNAi-related components. Genes Dev. 2007;21(20):2539–2544. doi: 10.1101/gad.451207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Endo S, Kubota S, Siomi H, Adachi A, Oroszlan S, Maki M, Hatanaka M. A region of basic amino-acid cluster in HIV-1 Tat protein is essential for trans-acting activity and nucleolar localization. Virus Genes. 1989;3(2):99–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00125123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fire A, Albertson D, Harrison SW, Moerman DG. Production of antisense RNA leads to effective and specific inhibition of gene expression in C. elegans muscle. Development. 1991;113:503–514. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallo RC. Tat as one key to HIV-induced immune pathogenesis and Tat toxoid as an important component of a vaccine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:8324–8326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gatignol A, Buckler-White A, Berkhout B, Jeang KT. Characterization of a human TAR RNA-binding protein that activates the HIV-1 LTR. Science. 1991;251:1597–1600. doi: 10.1126/science.2011739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giannini C, Bréchot C. Hepatitis C virus biology. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:S27–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo Z, Chen LM, Zeng H, Gomez JA, Plowden J, Fujita T, Katz JM, Donis RO, Sambhara S. NS1 protein of influenza A virus inhibits the function of intracytoplasmic pathogen sensor, RIG-I. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2007;36(3):263–269. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0283RC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hale BG, Randall RE, Ortín J, Jackson D. The multifunctional NS1 protein of influenza A viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2008;89:2359–2376. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/004606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hartman AL, Towner JS, Nichol ST. A C-terminal basic amino acid motif of Zaire Ebola virus VP35 is essential for type I interferon antagonism and displays high identity with the RNA-binding domain of another interferon antagonist, the NS1 protein of influenza A virus. Virol. 2004;328:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hatada E, Fukuda Binding of influenza A virus NS1 protein to dsRNA in vitro. J. Gen. Virol. 1992;73:3325–3329. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-12-3325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hatada E, Saito S, Okishio N, Fukuda R. Binding of the influenza virus NS1 protein to model genome RNAs. Virology. 1997;78:1059–1063. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-5-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hatada E, Takizawa T, Fukuda R. Specific binding of influenza A virus NS1 protein to the virus minus-sense RNA in vitro. J. Gen. Virol. 1992;73:17–25. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-1-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang J, Wang F, Argyris E, Chen K, Liang Z, Tian H, Huang W, Squires K, Verlinghieri G, Zhang H. Cellular microRNAs contribute to HIV-1 latency in resting primary CD4(+) T lymphocytes. Nat. Med. 2007;13:1241–1247. doi: 10.1038/nm1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hutvágner G, Zamore PD. A microRNA in a multiple-turnover RNAi enzyme complex. Science. 2002;297:2056–2060. doi: 10.1126/science.1073827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ji J, Glaser A, Wernli M, Berke JM, Moradpour D, Erb P. Suppression of short interfering RNA-mediated gene silencing by the structural proteins of hepatitis C virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2008;89:2761–2766. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/002923-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson RF, Bell P, Harty RN. Effect of Ebola virus proteins GP, NP and VP35 on VP40 VLP morphology. Virol. J. 2006a;3:31. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-3-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson RF, McCarthy SE, Godlewski PJ, Harty RN. Ebola virus VP35–VP40 interaction is sufficient for packaging 3E–5E minigenome RNA into virus-like particles. J. Virol. 2006 b;80:5135–5144. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01857-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karn J. Tackling tat. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;293:235–254. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kien F, Abraham JD, Schuster C, Kieny MP. Analysis of the subcellular localization of hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein in live cells using EGFP fusion proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 2003;84:561–566. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18927-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kanwar JR, Mahidhara G, Kanwar RK. MicroRNA in human cancer and chronic inflammatory diseases. Front Biosci. 2010 Jun 1;15:1113–26. doi: 10.2741/s121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karlowski WM, Zielezinski A, Carrère J, Pontier D, Lagrange T, Cooke R. Genome-wide computational identification of WG/GW Argonaute-binding proteins in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(13):4231–45. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kitajewski J, Schneider RJ, Safer B, Shenk T. An adenovirus mutant unable to express VAI RNA displays different growth responses and sensitivity to interferon in various host cell lines. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1986a;6:4493–4498. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.12.4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kitajewski J, Schneider RJ, Safer B, Munemitsu SM, Samuel CE, Thimmappaya B, Shenk T. Adenovirus VAI RNA antagonizes the antiviral action of interferon by preventing activation of the interferon-induced eIF-2 alpha kinase. Cell. 1986b;45(2):195–200. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kok KH, Jin DY. Influenza A virus NS1 protein does not suppress RNA interference in mammalian cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2006;87:2639–2644. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81764-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Langland JO, Jacobs BL. Inhibition of PKR by vaccinia virus: role of the N- and C-terminal domains of E3L. Virology. 2004;324(2):419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lantermann M, Schwantes A, Sliva K, Sutter G, Schnierle BS. Vaccinia virus double-stranded RNA-binding protein E3 does not interfere with siRNA-mediated gene silencing in mammalian cells. Virus Res. 2007;126:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lecellier CH, Dunoyer P, Arar K, Lehmann-Che J, Eyquem S, Himber C, Saib A, Voinnet O. A cellular microRNA mediates antiviral defense in human cells. Science. 2005;308:557–560. doi: 10.1126/science.1108784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin J, Cullen R. Analysis of the interaction of primate retroviruses with the human RNA interference machinery. J. Virol. 2007;81(22):12218–12226. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01390-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lin W, Kim SS, Yeung E, Kamegaya Y, Blackard JT, Kim KA, Holtzman MJ, Chung RT. Hepatitis C virus core protein blocks interferon signaling by interaction with the STAT1 SH2 domain. J. Virol. 2006;80(18):9226–9235. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00459-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Linial ML. Why aren't foamy viruses pathogenic? Trends in Microbiology. 2000;8:284–289. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01763-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu J, Lynch PA, Chien CY, Montelione GT, Krug RM, Berman HM. Crystal structure of the unique RNA-binding domain of the influenza virus NS1 protein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1997;4:896–899. doi: 10.1038/nsb1197-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu J, Rivas FV, Wohlschlegel J, Yates JR, III, Parker R, Hannon GJ. A role for the P-body component GW182 in microRNA function. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:1261–1266. doi: 10.1038/ncb1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lu S, Cullen BR. Adenovirus VA1 noncoding RNA can inhibit small interfering RNA and MicroRNA biogenesis. J. Virol. 2004;78:12868–12876. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12868-12876.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marq JB, Hausmann S, Luban J, Kolakofsky D, Garcin D. The double-stranded RNA binding domain of the vaccinia virus E3L protein inhibits both RNA- and DNA-induced activation of interferon beta. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284(38):25471–25478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mathews MB, Shenk T. Adenovirus virus-associated RNA and translation control. J Virol. 1991;65:5657–5662. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5657-5662.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Matskevich AA, Moelling K. Dicer is involved in protection against influenza A virus infection. J. Gen. Virol. 2007;88:2627–2635. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McJunkin JE, de los Reyes EC, Irazuzta JE, Caceres MJ, Khan RR, Minnich LL, Fu KD, Lovett GD, Tsai T, Thompson A. La Crosse encephalitis in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:801–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McKenna SA, Kim I, Liu CW, Puglisi JD. Uncoupling of RNA binding and PKR kinase activation by viral inhibitor RNAs. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;358(5):1270–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Melen K, Kinnunen L, Fagerlund R, Ikonen N, Twu KY, Krug RM, Julkunen I. Nuclear and nucleolar targeting of influenza A virus NS1 protein: striking differences between different virus subtypes. J. Virol. 2007;81:5995–6006. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01714-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Murakami Y, Aly HH, Tajima A, Inoue I, Shimotohno K. Regulation of the hepatitis C virus genome replication by miR-199a. J. Hepatol. 2009;50(3):453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Newby CM, Sabin L, Pekosz A. The RNA binding domain of influenza A virus NS1 protein affects secretion of tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-6, and interferon in primary murine tracheal epithelial cells. J. Virol. 2007;81:9469–9480. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00989-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Otsuka M, Jing Q, Georgel P, New L, Chen J, Mols J, Kang YJ, Jiang Z, Du X, Cook R, Das SC, Pattnaik AK, Beutler B, Han J. Hypersusceptibility to vesicular stomatitis virus infection in Dicer1-deficient mice is due to impaired miR24 and miR93 expression. Immunity. 2007;27:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ouellet DL, Plante I, Landry P, Barat C, Janelle ME, Flamand L, Tremblay MJ, Provost P. Identification of functional microRNAs released through asymmetrical processing of HIV-1 TAR element. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2008;36(7):2353–2365. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Qian S, Zhong X, Yu L, Ding B, de Haan P, Boris-Lawrie K. HIV-1 Tat RNA silencing suppressor activity is conserved across kingdoms and counteracts translational repression of HIV-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106(2):605–610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806822106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Santolini E, Migliaccio G, La Monica N. Biosynthesis and biochemical properties of the hepatitis C virus core protein. J. Virol. 1994;68(6):3631–3641. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3631-3641.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sen GL, Blau HM. Argonaute 2/RISC resides in sites of mammalian mRNA decay known as cytoplasmic bodies. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7(6):633–636. doi: 10.1038/ncb1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.St. Johnston D, Brown NH, Ga JG, Jantsch M. A conserved double-stranded RNA-binding domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:10979–10983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Suzuki R, Matsuura Y, Suzuki T, Ando A, Chiba J, Harada S, Saito I, Miyamura T. Nuclear localization of the truncated hepatitis C virus core protein with its hydrophobic C terminus deleted. J. Gen. Virol. 1995;76:53–61. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-1-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Triboulet R, Mari B, Lin YL, Chable-Bessia C, Bennasser Y, Lebrigand K, Cardinaud B, Maurin T, Barbry P, Baillat V, Reynes J, Corbeau P, Jeang KT, Benkirane M. Suppression of microRNA-silencing pathway by HIV-1 during virus replication. Science. 2007;315(5818):1579–1582. doi: 10.1126/science.1136319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang FZ, Weber F, Croce C, Liu CG, Liao X, Pellett PE. Human cytomegalovirus infection alters the expression of cellular microRNA species that affect its replication. J. Virol. 2008;82:9065–9074. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00961-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang W, Riedel K, Lynch P, Chien CY, Montelione GT, Krug RM. RNA binding by the novel helical domain of the influenza virus NS1 protein requires its dimer structure and a small number of specific basic amino acids. RNA. 1999;5:195–205. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299981621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang Y, Kato N, Jazag A, Dharel N, Otsuka M, Taniguchi H, Kawabe T, Omata M. Hepatitis C virus core protein is a potent inhibitor of RNA silencing-based antiviral response. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):883–892. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Weber F, Wagner V, Kessler N, Haller O. Induction of interferon synthesis by the PKR-inhibitory VA RNAs of adenoviruses. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Westerhout EM, Ooms M, Vink M, Das AT, Berkhout B. HIV-1 can escape from RNA interference by evolving an alternative structure in its RNA genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:796–804. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wianny F, Zernicka-Goetz M. Specific interference with gene function by double-stranded RNA in early mouse development. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:70–75. doi: 10.1038/35000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yasui K, Wakita T, Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Funahashi SI, Ichikawa M, Kajita T, Moradpour D, Wands JR, Kohara M. The native form and maturation process of hepatitis C virus core protein. J. Virol. 1998;72:6048–6055. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.6048-6055.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yuwen H, Cox JH, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR, Moss B. Nuclear localization of a double-stranded RNA-binding protein encoded by the vaccinia virus E3L gene. Virology. 1993;195(2):732–744. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zeng Y, Cullen BR. Sequence requirements for micro RNA processing and function in human cells. RNA. 2003;9:112–123. doi: 10.1261/rna.2780503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zeng Y, Yi R, Cullen BR. MicroRNAs and small interfering RNAs can inhibit mRNA expression by similar mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:9779–9784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1630797100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]